Rajneesh

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh | |

|---|---|

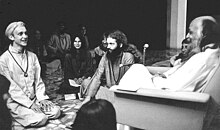

Rajneesh c. 1977 | |

| Born | Chandra Mohan Jain 11 December 1931 Kuchwada, Bhopal State, British India |

| Died | 19 January 1990 (aged 58) Pune, Maharashtra, India |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Education | Dr. Hari Singh Gour University (MA) |

| Known for | Spirituality, mysticism, anti-religion[1] |

| Movement | Neo-sannyasins[1] |

| Memorial(s) | Osho International Meditation Resort, Pune |

| Website | osho |

Rajneesh (born Chandra Mohan Jain; 11 December 1931 – 19 January 1990), also known as Acharya Rajneesh,[2] Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh,[1] and later as Osho (Hindi pronunciation: [ˈo:ʃo:]), was an Indian godman,[3] philosopher, mystic, and founder of the Rajneesh movement.[1] He was viewed as a controversial new religious movement leader during his life. He rejected institutional religions,[4][1][5] insisting that spiritual experience could not be organized into any one system of religious dogma.[6] As a guru, he advocated meditation and taught a unique form called dynamic meditation. Rejecting traditional ascetic practices, he advocated that his followers live fully in the world but without attachment to it.[6] In expressing a more progressive attitude to sexuality[7] he caused controversy in India during the late 1960s and became known as "the sex guru".[1][8][9]

Rajneesh experienced a spiritual awakening in 1953 at the age of 21.[6] Following several years in academia, in 1966 Rajneesh resigned his post at the University of Jabalpur and began traveling throughout India, becoming known as a vocal critic of the orthodoxy of mainstream religions,[1][10][11][7] as well as of mainstream political ideologies and of Mahatma Gandhi.[12][13][14] In 1970, Rajneesh spent time in Mumbai initiating followers known as "neo-sannyasins".[1] During this period, he expanded his spiritual teachings and commented extensively in discourses on the writings of religious traditions, mystics, bhakti poets[broken anchor], and philosophers from around the world. In 1974, Rajneesh relocated to Pune, where an ashram was established and a variety of therapies, incorporating methods first developed by the Human Potential Movement, were offered to a growing Western following.[15][16] By the late 1970s, the tension between the ruling Janata Party government of Morarji Desai and the movement led to a curbing of the ashram's development and a back tax claim estimated at $5 million.[17]

In 1981, the Rajneesh movement's efforts refocused on activities in the United States and Rajneesh relocated to a facility known as Rajneeshpuram in Wasco County, Oregon. The movement ran into conflict with county residents and the state government, and a succession of legal battles concerning the ashram's construction and continued development curtailed its success. In 1985, Rajneesh publicly asked local authorities to investigate his personal secretary Ma Anand Sheela and her close supporters for a number of crimes, including a 1984 mass food-poisoning attack intended to influence county elections, an aborted assassination plot on U.S. attorney Charles H. Turner, the attempted murder of Rajneesh's personal physician, and the bugging of his own living quarters; authorities later convicted several members of the ashram, including Sheela.[18] That year, Rajneesh was deported from the United States on separate immigration-related charges in accordance with an Alford plea.[19][20][21] After his deportation, 21 countries denied him entry.[22]

Rajneesh ultimately returned to Mumbai, India, in 1986. After staying in the house of a disciple where he resumed his discourses for six months, he returned to Pune in January 1987 and revived his ashram, where he died in 1990.[23][24] Rajneesh's ashram, now known as OSHO International Meditation Resort,[25] and all associated intellectual property, is managed by the registered Osho International Foundation (formerly Rajneesh International Foundation).[26][27] Rajneesh's teachings have had an impact on Western New Age thought,[28][29] and their popularity reportedly increased between the time of his death and 2005.[30][31]

Life

Childhood and adolescence: 1931–1950

Rajneesh (a childhood nickname from the Sanskrit रजनी, rajanee, "night", and ईश, isha, "lord", meaning the "God of Night" or "The Moon" (चंद्रमा) was born Chandra Mohan Jain, the eldest of 11 children of a cloth merchant, at his maternal grandparents' house in Kuchwada; a small village in the Raisen District of Madhya Pradesh state in India.[32][33][34] His parents, Babulal and Saraswati Jain, who were Taranpanthi Jains, let him live with his maternal grandparents until he was eight years old.[35] By Rajneesh's own account, this was a major influence on his development because his grandmother gave him the utmost freedom, leaving him carefree without an imposed education or restrictions.[36]

When he was seven years old, his grandfather died, and he went to Gadarwara to live with his parents.[32][37] Rajneesh was profoundly affected by his grandfather's death, and again by the death of his childhood girlfriend Shashi from typhoid when he was 15, leading to a preoccupation with death that lasted throughout much of his childhood and youth.[37][38] In his school years, he was a gifted and rebellious student, and gained a reputation as a formidable debater.[12] Rajneesh became critical of traditional religion, took an interest in many methods to expand consciousness, including breath control, yogic exercises, meditation, fasting, the occult, and hypnosis. According to Vasant Joshi, Rajneesh read widely from an early age, and although as a young boy, he played sports; reading was his primary interest.[39] After showing an interest in the writings of Marx and Engels, he was branded a communist and was threatened with expulsion from school. According to Joshi, with the help of friends, he built a small library containing mostly communist literature. Rajneesh, according to his uncle Amritlal, also formed a group of young people that regularly discussed communist ideology and their opposition to religion.[39]

Rajneesh was later to say, "I have been interested in communism from my very childhood...communist literature — perhaps there is no book that is missing from my library. I have signed and dated each book before 1950. Small details are so vivid before me, because that was my first entry into the intellectual world. First I was deeply interested in communism, but finding that it is a corpse I became interested in anarchism — that was also a Russian phenomenon — Prince Kropotkin, Bakunin, Leo Tolstoy. All three were anarchists: no state, no government in the world."[40]

He became briefly associated with socialism and two Indian nationalist organisations: the Indian National Army and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.[12][41][42] However, his membership in the organisations was short-lived as he could not submit to any external discipline, ideology, or system.[43]

University years and public speaker: 1951–1970

In 1951, aged 19, Rajneesh began his studies at Hitkarini College in Jabalpur.[44] Asked to leave after conflicts with an instructor, he transferred to D. N. Jain College, also in Jabalpur.[45] Having proved himself to be disruptively argumentative, he was not required to attend college classes at D. N. Jain College except for examinations and used his free time to work for a few months as an assistant editor at a local newspaper.[46] He began speaking in public at the annual Sarva Dharma Sammelan (Meeting of all faiths) held at Jabalpur, organised by the Taranpanthi Jain community into which he was born, and participated there from 1951 to 1968.[47] He resisted his parents' pressure to marry.[48] Rajneesh later said, he became spiritually enlightened on 21 March 1953, when he was 21 years old, in a mystical experience while sitting under a tree in the Bhanvartal garden in Jabalpur.[49]

Having completed his BA in philosophy at D. N. Jain College in 1955, he joined the University of Sagar, where in 1957, he earned his MA in philosophy (with distinction).[50] He immediately secured a teaching position at Raipur Sanskrit College, but the vice-chancellor soon asked him to seek a transfer as he considered him a danger to his students' morality, character, and religion.[13] From 1958, he taught philosophy as a lecturer at Jabalpur University, being promoted to professor in 1960.[13] A popular lecturer, he was acknowledged by his peers as an exceptionally intelligent man who had been able to overcome the deficiencies of his early small-town education.[51]

In parallel to his university job, he travelled throughout India under the name Acharya Rajneesh (Acharya means teacher or professor; Rajneesh was a nickname he had acquired in childhood), giving lectures critical of socialism, Gandhi, and institutional religions.[12][13][14] He travelled so much that he would find it difficult to sleep on a normal bed, because he had grown used to sleeping amid the rocking of railway coach berths.[52]

According to a speech given by Rajneesh in 1969, socialism is the ultimate result of capitalism, and capitalism itself, of revolution that brings about socialism.[39] Rajneesh stated that he believed that in India, socialism was inevitable, but fifty, sixty or seventy years hence, India should apply its efforts to first creating wealth.[53] He said that socialism would socialise only poverty, and he described Gandhi as a masochist reactionary who worshipped poverty.[12][14] What India needed to escape its backwardness was capitalism, science, modern technology, and birth control.[12] He did not regard capitalism and socialism as opposite systems, but considered it disastrous for any country to talk about socialism without first building a capitalist economy.[39] He criticised orthodox Indian religions as dead, filled with empty rituals, oppressing their followers with fears of damnation and promises of blessings.[12][14] Such statements made him controversial, but also gained him a loyal following that included a number of wealthy merchants and businessmen.[12][54] These people sought individual consultations from him about their spiritual development and transforming their daily lives, in return for donations and his practice snowballed.[54] From 1962, he began to lead 3- to 10-day meditation camps, and the first meditation centres (Jivan Jagruti Kendra) started to emerge around his teaching, then known as the Life Awakening Movement (Jivan Jagruti Andolan).[55] After a controversial speaking tour in 1966, he resigned from his teaching post at the request of the university.[13]

In a 1968 lecture series, later published under the title From Sex to Superconsciousness, he scandalised Hindu leaders by calling for freer acceptance of sex and became known as the "sex guru" in the Indian press.[9][7] When in 1969, he was invited to speak at the Second World Hindu Conference, despite the misgivings of some Hindu leaders, his statements raised controversy again when he said, "Any religion which considers life meaningless and full of misery and teaches the hatred of life, is not a true religion. Religion is an art that shows how to enjoy life."[56] He compared the treatment of lower caste shudras and women with the treatment of animals.[57] He characterised brahmin as being motivated by self-interest, provoking the Shankaracharya of Puri, who tried in vain to have his lecture stopped.[56]

Mumbai: 1971–1974

At a public meditation event in early 1970, Rajneesh presented his Dynamic Meditation method for the first time.[58] Dynamic Meditation involved breathing very fast and celebrating with music and dance.[59] He left Jabalpur for Mumbai at the end of June.[60] On 26 September 1970, he initiated his first group of disciples or neo-sannyasins.[61] Becoming a disciple apparently meant assuming a new name and wearing the traditional saffron dress of ascetic Hindu holy men, including a mala (beaded necklace) carrying a locket with his picture.[62] However, his sannyasins were encouraged to follow a celebratory rather than ascetic lifestyle.[63] He himself was not to be worshipped but regarded as a catalytic agent, "a sun encouraging the flower to open".[63]

He had by then, acquired a secretary, Laxmi Thakarsi Kuruwa, who as his first disciple had taken the name Ma Yoga Laxmi.[12] Laxmi was the daughter of one of his early followers, a wealthy Jain, who had been a key supporter of the Indian National Congress during the struggle for Indian independence, with close ties to Gandhi, Nehru, and Morarji Desai.[12] She raised the money that enabled Rajneesh to stop his travels and settle down.[12] In December 1970, he moved to the Woodlands Apartments in Mumbai, where he gave lectures and received visitors, among them his first Western visitors.[60] He now traveled rarely, no longer speaking at open public meetings.[60] In 1971, he adopted the title "Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh".[62]

Speaking about the name change from Acharya to Bhagwan, Rajneesh said in later years, "I loved the term. I said, 'At least for a few years that will do. Then we can drop it.'"

I have chosen it for a specific purpose and it has been serving well, because people who used to come to gather knowledge, they stopped. The day I called myself Bhagwan, they stopped. It was too much for them, it was too much for their egos, someone calling himself Bhagwan...It hurts the ego. Now I've changed my function absolutely. I started working on a different level, in a different dimension. Now I give you being, not knowledge. I was an acharya and they were students; they were learning. Now I am no more a teacher and you are not here as students. I am here to impart being. I am here to make you awaken. I am not here to give knowledge, I am going to give you knowing- and that is a totally different dimension.

Calling myself Bhagwan was simply symbolic – that now I have taken a different dimension to work. And it has been tremendously useful. All the wrong people automatically disappeared and a totally different quality of people started arriving. It worked well. It sorted out well, only those who are ready to dissolve with me, remained. All others escaped. They created space around me. Otherwise, they were crowding too much, and it was very difficult for the real seekers to come closer to me. The crowd disappeared. The word "Bhagwan" functioned like an atomic explosion. It did well. I am happy that I chose it."[64]

Shree is a polite form of address roughly equivalent to the English "Sir"; Bhagwan means "blessed one", used in Indian tradition as a term of respect for a human being in whom the divine is no longer hidden but apparent.[65] In Hinduism it can also be used to signify a deity or avatar.[66] In many parts of India and South Asia, Bhagwan represents the abstract concept of a universal God to Hindus who are spiritual and religious but do not worship a specific deity.[66]

Later, when he changed his name, he redefined the meaning of Bhagwan.[67]

Pune ashram: 1974–1981

The humid climate of Mumbai proved detrimental to Rajneesh's health: he developed diabetes, asthma, and numerous allergies.[62] In 1974, on the 21st anniversary of his experience in Jabalpur, he moved to a property in Koregaon Park, Pune, purchased with the help of Ma Yoga Mukta (Catherine Venizelos), a Greek shipping heiress.[68][69] Rajneesh spoke at the Pune ashram from 1974 to 1981. The two adjoining houses and 6 acres (2.4 ha) of land became the nucleus of an ashram, and the property is still the heart of the present-day OSHO International Meditation Resort. It allowed the regular audio recording and, later, video recording and printing of his discourses for worldwide distribution, enabling him to reach far larger audiences. The number of Western visitors increased sharply.[70] The ashram soon featured an arts-and-crafts centre producing clothes, jewellery, ceramics, and organic cosmetics and hosted performances of theatre, music, and mime.[70] From 1975, after the arrival of several therapists from the Human Potential Movement, the ashram began to complement meditations with a growing number of therapy groups,[15][16] which became a major source of income for the ashram.[71][72]

The Pune ashram was by all accounts an exciting and intense place to be, with an emotionally charged, madhouse-carnival atmosphere.[70][73][74] The day began at 6:00 a.m. with Dynamic Meditation.[75][76] From 8:00 am, Rajneesh gave a 60- to 90-minute spontaneous lecture in the ashram's "Buddha Hall" auditorium, commenting on religious writings or answering questions from visitors and disciples.[70][76] Until 1981, lecture series held in Hindi alternated with series held in English.[77] During the day, various meditations and therapies took place, whose intensity was ascribed to the spiritual energy of Rajneesh's "buddhafield".[73] In evening darshans, Rajneesh conversed with individual disciples or visitors and initiated disciples ("gave sannyas").[70][76] Sannyasins came for darshan when departing or returning or when they had anything they wanted to discuss.[70][76]

To decide which therapies to participate in, visitors either consulted Rajneesh or selected according to their own preferences.[78] Some of the early therapy groups in the ashram, such as the encounter group, were experimental, allowing a degree of physical aggression as well as sexual encounters between participants.[79][80] Conflicting reports of injuries sustained in Encounter group sessions began to appear in the press.[81][82][83] Richard Price, at the time a prominent Human Potential Movement therapist and co-founder of the Esalen Institute, found the groups encouraged participants to 'be violent' rather than 'play at being violent' (the norm in Encounter groups conducted in the United States), and criticised them for "the worst mistakes of some inexperienced Esalen group leaders".[84] Price is alleged to have exited the Pune ashram with a broken arm following a period of eight hours locked in a room with participants armed with wooden weapons.[84] Bernard Gunther, his Esalen colleague, fared better in Pune and wrote a book, Dying for Enlightenment, featuring photographs and lyrical descriptions of the meditations and therapy groups.[84] Violence in the therapy groups eventually ended in January 1979, when the ashram issued a press release stating that violence "had fulfilled its function within the overall context of the ashram as an evolving spiritual commune".[85]

Sannyasins who had "graduated" from months of meditation and therapy could apply to work in the ashram, in an environment that was consciously modelled on the community the Russian mystic Gurdjieff led in France in the 1930s.[86] Key features incorporated from Gurdjieff were hard, unpaid labour, and supervisors chosen for their abrasive personality, both designed to provoke opportunities for self-observation and transcendence.[86] Many disciples chose to stay for years.[86] Besides the controversy around the therapies, allegations of drug use amongst sannyasin began to mar the ashram's image.[87] Some Western sannyasins were alleged to be financing extended stays in India through prostitution and drug-running.[88][89] A few people later alleged that while Rajneesh was not directly involved, they discussed such plans and activities with him in darshan and he gave his blessing.[90]

By the latter 1970s, the Pune ashram was too small to contain the rapid growth and Rajneesh asked that somewhere larger be found.[91] Sannyasins from around India started looking for properties: those found included one in the province of Kutch in Gujarat and two more in India's mountainous north.[91] The plans were never implemented as mounting tensions between the ashram and the Janata Party government of Morarji Desai resulted in an impasse.[91] Land-use approval was denied and, more importantly, the government stopped issuing visas to foreign visitors who indicated the ashram as their main destination.[91][92] Besides, Desai's government cancelled the tax-exempt status of the ashram with retrospective effect, resulting in a claim estimated at $5 million.[17] Conflicts with various Indian religious leaders aggravated the situation—by 1980 the ashram had become so controversial that Indira Gandhi, despite a previous association between Rajneesh and the Indian Congress Party dating back to the sixties, was unwilling to intercede for it after her return to power.[17] In May 1980, during one of Rajneesh's discourses, an attempt on his life was made by Vilas Tupe, a young Hindu fundamentalist.[91][93][94] Tupe claims that he undertook the attack because he believed Rajneesh to be an agent of the CIA.[94]

By 1981, Rajneesh's ashram hosted 30,000 visitors per year.[87] Daily discourse audiences were by then predominantly European and American.[95][96] Many observers noted that Rajneesh's lecture style changed in the late '70s, becoming less focused intellectually and featuring an increasing number of ethnic or dirty jokes intended to shock or amuse his audience.[91] On 10 April 1981, having discoursed daily for nearly 15 years, Rajneesh entered a three-and-a-half-year period of self-imposed public silence, and satsangs—silent sitting with music and readings from spiritual works such as Khalil Gibran's The Prophet or the Isha Upanishad—replaced discourses.[97][98] Around the same time, Ma Anand Sheela (Sheela Silverman) replaced Ma Yoga Laxmi as Rajneesh's secretary.[99]

United States and the Oregon commune: 1981–1985

Arrival in the United States

In 1981, the increased tensions around the Pune ashram, along with criticism of its activities and threatened punitive action by Indian authorities, provided an impetus for the ashram to consider the establishment of a new commune in the United States.[100][101][102] According to Susan J. Palmer, the move to the United States was a plan from Sheela.[103] Sheela and Rajneesh had discussed the idea of establishing a new commune in the US in late 1980, although he did not agree to travel there until May 1981.[99] On 1 June that year he travelled to the United States on a tourist visa, ostensibly for medical purposes, and spent several months at a Rajneeshee retreat centre located at Kip's Castle in Montclair, New Jersey.[104][105] He had been diagnosed with a prolapsed disc in early 1981 and treated by several doctors, including James Cyriax, a St. Thomas' Hospital musculoskeletal physician and expert in epidural injections flown in from London.[99][106][107] Rajneesh's previous secretary, Laxmi, reported to Frances FitzGerald that "she had failed to find a property in India adequate to Rajneesh's needs, and thus, when the medical emergency came, the initiative had passed to Sheela".[107] A public statement by Sheela indicated that Rajneesh was in grave danger if he remained in India, but would receive appropriate medical treatment in America if he needed surgery.[99][106][108] Despite the stated serious nature of the situation, Rajneesh never sought outside medical treatment during his time in the United States, leading the Immigration and Naturalization Service to contend that he had a preconceived intent to remain there.[107] Years later, Rajneesh pleaded guilty to immigration fraud, while maintaining his innocence of the charges that he made false statements on his initial visa application about his alleged intention to remain in the US when he came from India.[nb 1][nb 2][nb 3]

Establishing Rajneeshpuram

On 13 June 1981, Sheela's husband, John Shelfer, signed a purchase contract to buy property in Oregon for US$5.75 million, and a few days later assigned the property to the US foundation. The property was a 64,229-acre (260 km2) ranch, previously known as "The Big Muddy Ranch" and located across two counties (Wasco and Jefferson).[109] It was renamed "Rancho Rajneesh" and Rajneesh moved there on 29 August.[110] Initial local community reactions ranged from hostility to tolerance, depending on distance from the ranch.[111] The press reported, and another study found, that the development met almost immediately with intense local, state, and federal opposition from the government, press, and citizenry. Within months a series of legal battles ensued, principally over land use.[112] Within a year of arriving, Rajneesh and his followers had become embroiled in a series of legal battles with their neighbours, the principal conflict relating to land use.[112] The commune leadership was uncompromising and behaved impatiently in dealing with the locals.[113] They were also insistent upon having demands met, and engaged in implicitly threatening and directly confrontational behaviour.[113] Whatever the true intention, the repeated changes in their stated plans looked to many like conscious deception.[113]

In May 1982 the residents of Rancho Rajneesh voted to incorporate it as the city of Rajneeshpuram.[112] The conflict with local residents escalated, with increasingly bitter hostility on both sides, and over the following years, the commune was subject to constant and coordinated pressures from various coalitions of Oregon residents.[112][114] 1000 Friends of Oregon immediately commenced and then prosecuted over the next six years numerous court and administrative actions to void the incorporation and cause buildings and improvement to be removed.[112][115][114] 1000 Friends publicly called for the city to be "dismantled". A 1000 Friends Attorney stated that if 1000 Friends won, the Foundation would be "forced to remove their sewer system and tear down many of the buildings.[116][113] At one point, the commune imported large numbers of homeless people from various US cities in a failed attempt to affect the outcome of an election, before releasing them into surrounding towns and leaving some to the State of Oregon to return to their home cities at the state's expense.[117][118] In March 1982, local residents formed a group called Citizens for Constitutional Cities to oppose the Ranch development.[119] An initiative petition was filed that would order the governor "'to contain, control and remove' the threat of invasion by an 'alien cult'".[115]

The Oregon legislature passed several bills that sought to slow or stop the development and the City of Rajneeshpuram—including HB 3080, which stopped distribution of revenue sharing funds for any city whose legal status had been challenged. Rajneeshpuram was the only city impacted.[120] The Governor of Oregon, Vic Atiyeh, stated in 1982 that since their neighbors did not like them, they should leave Oregon.[121] In May 1982, United States Senator Mark Hatfield called the INS in Portland. An INS memo stated that the Senator was "very concerned" about how this "religious cult" is "endangering the way of life for a small agricultural town ... and is a threat to public safety".[122] Such actions "often do have influence on immigration decisions". In 1983 the Oregon Attorney General filed a lawsuit seeking to declare the City void because of an alleged violation of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the Constitution. The Court found that the City property was owned and controlled by the Foundation, and entered judgement for the State.[123] The court disregarded the controlling US constitutional cases requiring that a violation be redressed by the "least intrusive means" necessary to correct the violation, which it had earlier cited. The city was forced to "acquiesce" in the decision, as part of a settlement of Rajneesh's immigration case.[124]

While the various legal battles ensued Rajneesh remained behind the scenes, having withdrawn from a public facing role in what commune leadership referred to as a period of "silence." During this time, which lasted until November 1984, in lieu of Rajneesh speaking publicly, videos of his discourses were played to commune audiences.[104] His time was allegedly spent mostly in seclusion and he communicated only with a few key disciples, including Ma Anand Sheela and his caretaker girlfriend Ma Yoga Vivek (Christine Woolf).[104] He lived in a trailer next to a covered swimming pool and other amenities. At this time he did not lecture and interacted with followers via a Rolls-Royce 'drive-by' ceremony.[125] He also gained public notoriety for amassing a large collection of Rolls-Royce cars, eventually numbering 93 vehicles.[126][127] In 1981 he had given Sheela limited power of attorney, removing any remaining limits the following year.[128] In 1983, Sheela announced that he would henceforth speak only with her.[129] He later said that she kept him in ignorance.[128] Many sannyasins expressed doubts about whether Sheela properly represented Rajneesh and many dissidents left Rajneeshpuram in protest of its autocratic leadership.[130] Resident sannyasins without US citizenship experienced visa difficulties that some tried to overcome by marriages of convenience.[131] Commune administrators tried to resolve Rajneesh's own difficulty in this respect by declaring him the head of a religion, "Rajneeshism".[125][132]

During the Oregon years there was an increased emphasis on Rajneesh's prediction that the world might be destroyed by nuclear war or other disasters in the 1990s.[133] Rajneesh had said as early as 1964 that "the third and last war is now on the way" and frequently spoke of the need to create a "new humanity" to avoid global suicide.[134] This now became the basis for a new exclusivity, and a 1983 article in the Rajneesh Foundation Newsletter, announcing that "Rajneeshism is creating a Noah's Ark of consciousness ... I say to you that except this there is no other way", increased the sense of urgency in building the Oregon commune.[134] In March 1984, Sheela announced that Rajneesh had predicted the death of two-thirds of humanity from AIDS.[134][135] Sannyasins were required to wear rubber gloves and condoms if they had sex, and to refrain from kissing, measures widely represented in the press as an extreme over-reaction since condoms were not usually recommended for AIDS prevention because AIDS was considered a homosexual disease at that stage.[136][137] During his residence in Rajneeshpuram, Rajneesh also dictated three books under the influence of nitrous oxide administered to him by his private dentist: Glimpses of a Golden Childhood, Notes of a Madman and Books I Have Loved.[138] Sheela later stated that Rajneesh took sixty milligrams of valium each day and was addicted to nitrous oxide.[139][140][141] Rajneesh denied these charges when questioned about them by journalists.[139][142]

At the peak of the Rajneeshpuram era, Rajneesh, assisted by a sophisticated legal and business infrastructure, had created a corporate machine consisting of various front companies and subsidiaries.[143] At this time, the three main identifiable entities within his organisation were: the Ranch Church, or Rajneesh International Foundation (RIF); the Rajneesh Investment Corporation (RIC), through which the RIF was managed; and the Rajneesh Neo-Sannyasin International Commune (RNSIC). The umbrella organisation that oversaw all investment activities was Rajneesh Services International Ltd., a company incorporated in the UK but based in Zürich. There were also smaller organisations, such as Rajneesh Travel Corp, Rajneesh Community Holdings, and the Rajneesh Modern Car Collection Trust, whose sole purpose was to deal with the acquisition and rental of Rolls-Royces.[144][145]

1984 bioterror attack

Rajneesh had coached Sheela in using media coverage to her advantage and during his period of public silence he privately stated that when Sheela spoke, she was speaking on his behalf.[123] He had also supported her when disputes about her behaviour arose within the commune leadership, but in early 1984, as tension amongst the inner circle peaked, a private meeting was convened with Sheela and his personal house staff.[123] According to the testimony of Rajneesh's dentist, Swami Devageet (Charles Harvey Newman),[146] she was admonished during a meeting, with Rajneesh declaring that his house, and not hers, was the centre of the commune.[123] Devageet claimed Rajneesh warned that Sheela's jealousy of anyone close to him would inevitably make them a target.[123]

Several months later, on 30 October 1984, he ended his period of public silence, announcing that it was time to "speak his own truths".[147][148] On 19 December, Rajneesh was asked if organisation was necessary for a religion to survive.[149] Disciples present during the talk remember Rajneesh stating that "I will not leave you under a fascist regime".[149][150][146] According to the testimony of Rajneesh's dentist, Swami Devageet, this statement seemed directly aimed at Sheela - or to be directly against the present organisational structure.[146] The next day, sannyasins usually responsible for the editing and transcribing of the talks into book form were told by the management that the tapes of the discourse had been irreparably damaged by technical trouble and were unavailable.[146][151][152][149] After rumours that Sheela had suppressed the discourse grew, Sheela created a transcription of the talk, which was reproduced in The Rajneesh Times.[146][151][152] All suggestions that Rajneeshpuram itself had become a fascist state and Sheela was, in the words of Ma Prem Sangeet, "Hitler in a red dress", had been deleted.[149][150]

Rajneesh spoke almost daily, except for a three-month gap between April and July 1985.[149] In July, he resumed daily public discourses; on 16 September, a few days after Sheela and her entire management team had suddenly left the commune for Europe, Rajneesh held a press conference in which he labelled Sheela and her associates a "gang of fascists".[18] He accused them of having committed serious crimes, most dating back to 1984, and invited the authorities to investigate.[18]

The alleged crimes, which he stated had been committed without his knowledge or consent, included the attempted murder of his personal physician, poisonings of public officials in Oregon, wiretapping and bugging within the commune and within his own home, and a potentially lethal bioterror attack sickening 751 citizens of The Dalles, using Salmonella to impact county elections.[18] While his allegations were initially greeted with scepticism by outside observers,[153] the subsequent investigation by U.S. authorities confirmed these accusations and resulted in the conviction of Sheela and several of her lieutenants.[154] On 30 September 1985, Rajneesh denied that he was a religious teacher.[155] His disciples burned 5,000 copies the book Rajneeshism: An Introduction to Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and His Religion a 78-page compilation of his teachings that defined "Rajneeshism" as "a religionless religion".[156][155][157] He said he ordered the book-burning to rid the sect of the last traces of the influence of Sheela, whose robes were also "added to the bonfire".[155]

The salmonella attack is considered the first confirmed instance of chemical or biological terrorism to have occurred in the United States.[158] Rajneesh stated that because he was in silence and isolation, meeting only with Sheela, he was unaware of the crimes committed by the Rajneeshpuram leadership until Sheela and her "gang" left and sannyasins came forward to inform him.[159] A number of commentators have stated that they believe that Sheela was being used as a convenient scapegoat.[159][160][161] Others have pointed to the fact that although Sheela had bugged Rajneesh's living quarters and made her tapes available to the U.S. authorities as part of her own plea bargain, no evidence has ever come to light that Rajneesh had any part in her crimes.[162][163][164] It was, however, reported that Charles Turner, David Frohnmayer, and other law enforcement officials, who had surveyed affidavits never released publicly and who listened to hundreds of hours of tape recordings, insinuated to him that Rajneesh was guilty of more crimes than those for which he was eventually prosecuted.[165] Frohnmayer asserted that Rajneesh's philosophy was not "disapproving of poisoning" and that he felt he and Sheela had been "genuinely evil".[165]

Nonetheless, U.S. Attorney Turner and Oregon Attorney General Frohnmeyer acknowledged that "they had little evidence of (Rajneesh) being involved in any of the criminal activities that unfolded at the ranch".[166] According to court testimony by Ma Ava (Ava Avalos), a prominent disciple, Sheela played associates a tape recording of a meeting she had with Rajneesh about the "need to kill people" to strengthen wavering sannyasins' resolve in participating in her murderous plots, but it was difficult to hear, so Sheela produced a transcript of the tape. "She came back to the meeting and ... began to play the tape. It was a little hard to hear what he was saying. ... But Param Bodhi, assisted her, and went and transcribed it. And the gist of Bhagwan's response, yes, it was going to be necessary to kill people to stay in Oregon. And that actually killing people wasn't such a bad thing. And actually Hitler was a great man, although he could not say that publicly because nobody would understand that. Hitler had great vision."[118][167] Rajneesh's personal attorney Philip Niren Toelkes, wrote in 2021 that, "As is fully supported in the testimony of Ava Avalos, an admitted co-conspirator, Sheela presented Osho with a general question about whether people would have to die if the Community was attacked and used his general response that it would perhaps be necessary. Sheela then took an edited recording and 'transcript' of the recording, prepared under her control, back to a meeting to justify her planned criminal actions and overcome the reservations of her co-conspirators."[168] Ava Avalos also said in her testimony to the FBI investigators that "Sheela informed them that Bhagwan was not to know what was going on, and that if Bhagwan were to ask them about anything that would occur, 'they would have to lie to Bhagwan'."[169]

Sheela initiated attempts to murder Rajneesh's caretaker and girlfriend, Ma Yoga Vivek, and his personal physician, Swami Devaraj (George Meredith), because she thought that they were a threat to Rajneesh. She had secretly recorded a conversation between Devaraj and Rajneesh "in which the doctor agreed to obtain drugs the guru wanted to ensure a peaceful death if he decided to take his own life".[118] When asked if he was targeted because of a plan to give the guru euthanasia in an 2018 interview with ‘The Cut’, Rajneesh's doctor denied this and claimed that "She attacked his household and everybody in it and found any excuse she could to do that. She constantly hated the fact that we had access to Osho. We were a constant threat to her total monopoly on power. "[170]

On 23 October 1985, a federal grand jury indicted Rajneesh and several other disciples with conspiracy to evade immigration laws.[171] The indictment was returned in camera, but word was leaked to Rajneesh's lawyer.[171] Negotiations to allow Rajneesh to surrender to authorities in Portland if a warrant were issued failed.[171][172] Rumours of a national guard takeover and a planned violent arrest of Rajneesh led to tension and fears of shooting.[173] On the strength of Sheela's tape recordings, authorities later said they believed that there had been a plan that sannyasin women and children would have been asked to create a human shield if authorities tried to arrest Rajneesh at the commune.[165] On 28 October, Rajneesh and a small number of sannyasins accompanying him were arrested aboard two rented Learjets in North Carolina at Charlotte Douglas International Airport;[174] according to federal authorities the group was en route to Bermuda to avoid prosecution.[175][176][177][178] Cash amounting to $58,000, as well as 35 watches and bracelets worth a combined $1 million, were found on the aircraft.[173][179][180] Rajneesh had by all accounts been informed neither of the impending arrest nor the reason for the journey.[172] Officials took the full ten days legally available to transfer him from North Carolina to Portland for arraignment,[181] which included three nights near Oklahoma City.[178][182][183]

In Portland on 8 November before U.S. District Court Judge Edward Leavy, Rajneesh pleaded "not guilty" to all 34 charges, was released on $500,000 bail, and returned to the commune at Rajneeshpuram.[184][185][186][187] On the advice of his lawyers, he later entered an "Alford plea"—a type of guilty plea through which a suspect does not admit guilt, but does concede there is enough evidence to convict him—to one count of having a concealed intent to remain permanently in the U.S. at the time of his original visa application in 1981 and one count of having conspired to have sannyasins enter into a sham marriage to acquire U.S. residency.[188] Under the deal his lawyers made with the U.S. Attorney's office he was given a ten-year suspended sentence, five years' probation, and a $400,000 penalty in fines and prosecution costs and agreed to leave the United States, not returning for at least five years without the permission of the U.S. Attorney General.[19][154][180][189]

As to "preconceived intent", at the time of the investigation and prosecution, federal court appellate cases and the INS regulations permitted "dual intent", a desire to stay, but a willingness to comply with the law if denied permanent residence. Further, the relevant intent is that of the employer, not the employee.[190] Given the public nature of Rajneesh's arrival and stay, and the aggressive scrutiny by the INS, Rajneesh would appear to have had to be willing to leave the U.S. if denied benefits. The government nonetheless prosecuted him based on preconceived intent. As to arranging a marriage, the government only claimed that Rajneesh told someone who lived in his house that they should marry to stay.[190] Such encouragement appears to constitute incitement, a crime in the United States, but not a conspiracy, which requires the formation of a plan and acts in furtherance.[citation needed]

Travels and return to Pune: 1985–1990

Following his exit from the US, Rajneesh returned to India, landing in Delhi on 17 November 1985. He was given a hero's welcome by his Indian disciples and denounced the United States, saying the world must "put the monster America in its place" and that "Either America must be hushed up or America will be the end of the world."[191] He then stayed for six weeks in Manali, Himachal Pradesh. In Manali, Rajneesh said that he was interested in buying, for use as a possible new commune site, an atoll in the South Pacific that Marlon Brando was trying to sell. According to Rajneesh, the island could be made much bigger by the addition of houseboats and Japanese style floating gardens.[192] Sannyasins visited the island, but it was deemed unsuitable after they realised the area was prone to hurricanes.[193][194] When non-Indians in his party had their visas revoked, he moved on to Kathmandu, Nepal, and then, a few weeks later, to Crete. Arrested after a few days by the Greek National Intelligence Service (KYP), he flew to Geneva, then to Stockholm and London, but was in each case refused entry. Next Canada refused landing permission, so his plane returned to Shannon airport, Ireland, to refuel. There he was allowed to stay for two weeks at a hotel in Limerick, on condition that he did not go out or give talks. He had been granted a Uruguayan identity card, one-year provisional residency and a possibility of permanent residency, so the party set out, stopping at Madrid, where the plane was surrounded by the Guardia Civil. He was allowed to spend one night at Dakar, then continued to Recife and Montevideo. In Uruguay, the group moved to a house at Punta del Este where Rajneesh began speaking publicly until 19 June, after which he was "invited to leave" for no official reason. A two-week visa was arranged for Jamaica, but on arrival in Kingston police gave the group 12 hours to leave. Refuelling in Gander and in Madrid, Rajneesh returned to Bombay, India, on 30 July 1986.[195][196]

In January 1987, Rajneesh returned to the ashram in Pune[197][198] where he held evening discourses each day, except when interrupted by intermittent ill health.[199][200] Publishing and therapy resumed and the ashram underwent expansion,[199][200] now as a "Multiversity" where therapy was to function as a bridge to meditation.[200] Rajneesh devised new "meditation therapy" methods such as the "Mystic Rose" and began to lead meditations in his discourses after a gap of more than ten years.[199][200] His western disciples formed no large communes, mostly preferring ordinary independent living.[201] Red/orange dress and the mala were largely abandoned, having been optional since 1985.[200] The wearing of maroon robes—only while on ashram premises—was reintroduced in the summer of 1989, along with white robes worn for evening meditation and black robes for group leaders.[200]

In November 1987, Rajneesh expressed his belief that his deteriorating health (nausea, fatigue, pain in extremities, and lack of resistance to infection) was due to poisoning by the US authorities while in prison.[202] His doctors and former attorney, Philip Toelkes (Swami Prem Niren), hypothesised radiation and thallium in a deliberately irradiated mattress, since his symptoms were concentrated on the right side of his body,[202] but presented no hard evidence.[203] US attorney Charles H. Hunter described this as "complete fiction", while others suggested exposure to HIV or chronic diabetes and stress.[202][204]

From early 1988, Rajneesh's discourses focused exclusively on Zen.[199] In early 1989, Rajneesh gave a series of some of the longest lectures he had given, titled "Communism and Zen Fire, Zen Wind", in which he criticised capitalism and spoke of the possibilities of sannyas in Russia. In these talks he stated that communism could evolve into spiritualism, and spiritualism into anarchism.[205][206] "I have always been very scientific in my approach, either outside or inside. Communism can be the base. Then spirituality has to be its growth, to provide what is missing."[206] In late December, he said he no longer wished to be referred to as "Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh", and in February 1989 took the name "Osho Rajneesh", shortened to "Osho" in September.[199][207] He also requested that all trademarks previously branded with "Rajneesh" be rebranded "OSHO".[208][26] His health continued to weaken. He delivered his last public discourse in April 1989, from then on simply sitting in silence with his followers.[202] Shortly before his death, Rajneesh suggested that one or more audience members at evening meetings (now referred to as the White Robe Brotherhood) were subjecting him to some form of evil magic.[209][210] A search for the perpetrators was undertaken, but none could be found.[209][210]

Death

At age 58, Rajneesh died on 19 January 1990 at the ashram in Pune, India.[211][212] The official cause of death was heart failure, but a statement released by his commune said that he died because "living in the body had become a hell" after an alleged poisoning in U.S. jails.[213] His ashes were placed in his newly built bedroom in Lao Tzu House at the ashram in Pune. The epitaph reads, "Never Born – Never Died Only visited this planet Earth between December 11, 1931 and January 19, 1990".[214]

Teachings

Rajneesh's teachings, delivered through his discourses, were not presented in an academic setting, but interspersed with jokes.[215][216] The emphasis was not static but changed over time: Rajneesh revelled in paradox and contradiction, making his work difficult to summarise.[217] He delighted in engaging in behaviour that seemed entirely at odds with traditional images of enlightened individuals; his early lectures in particular were famous for their humour and their refusal to take anything seriously.[218][219] All such behaviour, however capricious and difficult to accept, was explained as "a technique for transformation" to push people "beyond the mind".[218]

He spoke on major spiritual traditions including Jainism, Hinduism, Hassidism, Tantrism, Taoism, Sikhism, Sufism, Christianity, Buddhism, on a variety of Eastern and Western mystics and on sacred scriptures such as the Upanishads and the Guru Granth Sahib.[220] The sociologist Lewis F. Carter saw his ideas as rooted in Hindu advaita, in which the human experiences of separateness, duality and temporality are held to be a kind of dance or play of cosmic consciousness in which everything is sacred, has absolute worth and is an end in itself.[221] While his contemporary Jiddu Krishnamurti did not approve of Rajneesh, there are clear similarities between their respective teachings.[217]

Rajneesh also drew on a wide range of Western ideas.[220] His belief in the unity of opposites recalls Heraclitus, while his description of man as a machine, condemned to the helpless acting out of unconscious, neurotic patterns, has much in common with Sigmund Freud and George Gurdjieff.[217][222] His vision of the "new man" transcending constraints of convention is reminiscent of Friedrich Nietzsche's Beyond Good and Evil;[223] his promotion of sexual liberation bears comparison to D. H. Lawrence;[224] and his "dynamic" meditations owe a debt to Wilhelm Reich.[225]

Ego and the mind

According to Rajneesh every human being is a Buddha with the capacity for enlightenment, capable of unconditional love and of responding rather than reacting to life, although the ego usually prevents this, identifying with social conditioning and creating false needs and conflicts and an illusory sense of identity that is nothing but a barrier of dreams.[226][227][228] Otherwise man's innate being can flower in a move from the periphery to the centre.[226][228]

Rajneesh viewed the mind first and foremost as a mechanism for survival, replicating behavioural strategies that have proven successful.[226][228] But the mind's appeal to the past, he said, deprives human beings of the ability to live authentically in the present, causing them to repress genuine emotions and to shut themselves off from joyful experiences that arise naturally when embracing the present moment: "The mind has no inherent capacity for joy. ... It only thinks about joy."[228][229] The result is that people poison themselves with all manner of neuroses, jealousies, and insecurities.[230] He argued that psychological repression, often advocated by religious leaders, makes suppressed feelings re-emerge in another guise, and that sexual repression resulted in societies obsessed with sex.[230] Instead of suppressing, people should trust and accept themselves unconditionally.[228][229] This should not merely be understood intellectually, as the mind could only assimilate it as one more piece of information: instead meditation was needed.[230]

Meditation

Rajneesh presented meditation not just as a practice, but as a state of awareness to be maintained in every moment, a total awareness that awakens the individual from the sleep of mechanical responses conditioned by beliefs and expectations.[228][230] He employed Western psychotherapy in the preparatory stages of meditation to create awareness of mental and emotional patterns.[231]

He suggested more than a hundred meditation techniques in total.[231][232] His own "active meditation" techniques are characterised by stages of physical activity leading to silence.[231] The most famous of these remains dynamic meditation,[231][232] which has been described as a kind of microcosm of his outlook.[232] Performed with closed or blindfolded eyes, it comprises five stages, four of which are accompanied by music.[233] First the meditator engages in ten minutes of rapid breathing through the nose.[233] The second ten minutes are for catharsis: "Let whatever is happening happen. ... Laugh, shout, scream, jump, shake—whatever you feel to do, do it!"[231][233] Next, for ten minutes one jumps up and down with arms raised, shouting Hoo! each time one lands on the flat of the feet.[233][234] At the fourth, silent stage, the meditator stops moving suddenly and totally, remaining completely motionless for fifteen minutes, witnessing everything that is happening.[233][234] The last stage of the meditation consists of fifteen minutes of dancing and celebration.[233][234]

Rajneesh developed other active meditation techniques, such as the Kundalini "shaking" meditation and the Nadabrahma "humming" meditation, which are less animated, although they also include physical activity of one sort or another.[231] He also used to organise Gibberish sessions in which disciples were asked to just blabber meaningless sounds, which according to him clears out garbage from mind and relaxes it.[235][236] His later "meditative therapies" require sessions for several days, OSHO Mystic Rose comprising three hours of laughing every day for a week, three hours of weeping each day for a second week, and a third week with three hours of silent meditation.[237] These processes of "witnessing" enable a "jump into awareness".[231] Rajneesh believed such cathartic methods were necessary because it was difficult for modern people to just sit and enter meditation. Once these methods had provided a glimpse of meditation, then people would be able to use other methods without difficulty.[citation needed]

Sannyas

Another key ingredient was his own presence as a master: "A Master shares his being with you, not his philosophy. ... He never does anything to the disciple."[218] The initiation he offered was another such device: "... if your being can communicate with me, it becomes a communion. ... It is the highest form of communication possible: a transmission without words. Our beings merge. This is possible only if you become a disciple."[218] Ultimately though, as an explicitly "self-parodying" guru, Rajneesh even deconstructed his own authority, declaring his teaching to be nothing more than a "game" or a joke.[219][238] He emphasised that anything and everything could become an opportunity for meditation.[218]

Renunciation and the "New Man"

Rajneesh saw his "neo-sannyas" as a totally new form of spiritual discipline, or one that had once existed but since been forgotten.[239] He thought that the traditional Hindu sannyas had turned into a mere system of social renunciation and imitation.[239] He emphasised complete inner freedom and the responsibility to oneself, not demanding superficial behavioural changes, but a deeper, inner transformation.[239] Desires were to be accepted and surpassed rather than denied.[239] Once this inner flowering had taken place, desires such as that for sex would be left behind.[239]

Rajneesh said that he was "the rich man's guru" and that material poverty was not a genuine spiritual value.[240] He had himself photographed wearing sumptuous clothing and hand-made watches[241] and, while in Oregon, drove a different Rolls-Royce each day – his followers reportedly wanted to buy him 365 of them, one for each day of the year.[242] Publicity shots of the Rolls-Royces were sent to the press.[240][243] They may have reflected both his advocacy of wealth and his desire to provoke American sensibilities, much as he had enjoyed offending Indian sensibilities earlier.[240][244]

Rajneesh aimed to create a "new man" combining the spirituality of Gautama Buddha with the zest for life embodied by Nikos Kazantzakis' Zorba the Greek: "He should be as accurate and objective as a scientist ... as sensitive, as full of heart, as a poet ... [and as] rooted deep down in his being as the mystic."[218][245] His term the "new man" applied to men and women equally, whose roles he saw as complementary; indeed, most of his movement's leadership positions were held by women.[246] This new man, "Zorba the Buddha", should reject neither science nor spirituality but embrace both.[218] Rajneesh believed humanity was threatened with extinction due to over-population, impending nuclear holocaust and diseases such as AIDS, and thought many of society's ills could be remedied by scientific means.[218] The new man would no longer be trapped in institutions such as family, marriage, political ideologies and religions.[219][246] In this respect Rajneesh is similar to other counter-culture gurus, and perhaps even certain postmodern and deconstructional thinkers.[219] Rajneesh said that the new man had to be "utterly ambitionless", as opposed to a life that depended on ambition. The new man, he said, "is not necessarily the better man. He will be livelier. He will be more joyous. He will be more alert. But who knows whether he will be better or not? As far as politicians are concerned, he will not be better, because he will not be a better soldier. He will not be ready to be a soldier at all. He will not be competitive, and the whole competitive economy will collapse. "[149][247]

"Heart to heart communion"

In April 1981, Rajneesh had sent a message that he was entering the ultimate stage of his work, and would now speak only through silence.[205][248] On 1 May 1981, Rajneesh stopped speaking publicly and entered a phase of "silent heart to heart communion".[249][250]

Rajneesh stated in the first talk he gave after ending three years of public silence on 30 October 1984, that he had gone into silence partly to put off those who were only intellectually following him.[251][252]

"First, my silence was not because I have said everything. My silence was because I wanted to drop those people who were hanging around my words. I wanted people who can be with me even if I am silent. I sorted out all those people without any trouble. They simply dropped out. Three years was enough time. And when I saw all those people – and they were not many, but they were hanging around my words. I don't want people to just believe in my words; I want people to live my silence. In these three years it was a great time to be silent with my people, and to see their courage and their love in remaining with a man who perhaps may never speak again. I wanted people who can be with me even if I am silent."[252]

Rajneesh's "Ten Commandments"

In his early days as Acharya Rajneesh, a correspondent once asked for his "Ten Commandments". In reply, Rajneesh said that it was a difficult matter because he was against any kind of commandment, but "just for fun", set out the following:

- 1 Never obey anyone's command unless it is coming from within you also.

- 2 There is no God other than life itself.

- 3 Truth is within you, do not search for it elsewhere.

- 4 Love is prayer.

- 5 To become a nothingness is the door to truth. Nothingness itself is the means, the goal and attainment.

- 6 Life is now and here.

- 7 Live wakefully.

- 8 Do not swim – float.

- 9 Die each moment so that you can be new each moment.

- 10 Do not search. That which is, is. Stop and see.

- — Osho (Osho's Ten Commandments)

He underlined numbers 3, 7, 9 and 10. The ideas expressed in these commandments have remained constant leitmotifs in his movement.[253]

Legacy

While Rajneesh's teachings were not welcomed by many in his own home country during his lifetime, there has been a change in Indian public opinion since Rajneesh's death.[254][255] In 1991, an Indian newspaper counted Rajneesh, along with figures such as Gautama Buddha and Mahatma Gandhi, among the ten people who had most changed India's destiny; in Rajneesh's case, by "liberating the minds of future generations from the shackles of religiosity and conformism".[256] Rajneesh has found more acclaim in his homeland since his death than he did while alive.[30] Writing in The Indian Express, columnist Tanweer Alam stated, "The late Rajneesh was a fine interpreter of social absurdities that destroyed human happiness."[257] At a celebration in 2006, marking the 75th anniversary of Rajneesh's birth, Indian singer Wasifuddin Dagar said that Rajneesh's teachings are "more pertinent in the current milieu than they were ever before".[258] In Nepal, there were 60 Rajneesh centres with almost 45,000 initiated disciples as of January 2008.[259] Rajneesh's entire works have been placed in the Library of India's National Parliament in New Delhi.[255] The Bollywood actor, and former Minister of State for External Affairs, Vinod Khanna, worked as Rajneesh's gardener in Rajneeshpuram in the 1980s.[260] Over 650 books[261] are credited to Rajneesh, expressing his views on all facets of human existence.[262] Virtually all of them are renderings of his taped discourses.[262] Many Bollywood personalities like Parveen Babi and Mahesh Bhatt were also known to be the followers of Rajneesh's philosophy.[263] His books are available in more than 60 languages from more than 200 publishing houses[264] and have entered best-seller lists in Italy and South Korea.[256] [265][266]

Rajneesh continues to be known and published worldwide in the area of meditation and his work also includes social and political commentary.[267] Internationally, after almost two decades of controversy and a decade of accommodation, Rajneesh's movement has established itself in the market of new religions.[267] His followers have redefined his contributions, reframing central elements of his teaching so as to make them appear less controversial to outsiders.[267] Societies in North America and Western Europe have met them half-way, becoming more accommodating to spiritual topics such as yoga and meditation.[267] The Osho International Foundation (OIF) runs stress management seminars for corporate clients such as IBM and BMW, with a reported (2000) revenue between $15 and $45 million annually in the US.[268][269] In Italy, a satirical Facebook page titled Le più belle frasi di Osho repurposing pictures of Osho with humorous captions about national politics was launched in 2016 and quickly surpassed a million followers, becoming a cultural phenomenon in the country, with posts being republished by national papers and being shown on television.[270]

Rajneesh's ashram in Pune has become the OSHO International Meditation Resort[271] Describing itself as the Esalen of the East, it teaches a variety of spiritual techniques from a broad range of traditions and promotes itself as a spiritual oasis, a "sacred space" for discovering one's self and uniting the desires of body and mind in a beautiful resort environment.[31] According to press reports, prominent visitors have included politicians and media personalities.[271] In 2011, a national seminar on Rajneesh's teachings was inaugurated at the Department of Philosophy of the Mankunwarbai College for Women in Jabalpur.[272] Funded by the Bhopal office of the University Grants Commission, the seminar focused on Rajneesh's "Zorba the Buddha" teaching, seeking to reconcile spirituality with the materialist and objective approach.[272] As of 2013, the resort required all guests to be tested for HIV/AIDS at its Welcome Centre on arrival.[273]

Reception

Rajneesh is generally considered one of the most controversial spiritual leaders to have emerged from India in the twentieth century.[274][275] His message of sexual, emotional, spiritual, and institutional liberation, as well as the pleasure he took in causing offence, ensured that his life was surrounded by controversy.[246] Rajneesh became known as the "sex guru" in India, and as the "Rolls-Royce guru" in the United States.[240] He attacked traditional concepts of nationalism, openly expressed contempt for politicians, and poked fun at the leading figures of various religions, who in turn found his arrogance insufferable.[276][277] His teachings on sex, marriage, family, and relationships contradicted traditional values and aroused a great deal of anger and opposition around the world.[105][278] His movement was widely considered a cult. Rajneesh was seen to live "in ostentation and offensive opulence", while his followers, most of whom had severed ties with outside friends and family and donated all or most of their money and possessions to the commune, might be at a mere "subsistence level".[117][279]

Appraisal by scholars of religion

Academic assessments of Rajneesh's work have been mixed and often directly contradictory.[citation needed] Uday Mehta saw errors in his interpretation of Zen and Mahayana Buddhism, speaking of "gross contradictions and inconsistencies in his teachings" that "exploit" the "ignorance and gullibility" of his listeners.[280] The sociologist Bob Mullan wrote in 1983 of "a borrowing of truths, half-truths and occasional misrepresentations from the great traditions... often bland, inaccurate, spurious and extremely contradictory".[281] American religious studies professor Hugh B. Urban also said Rajneesh's teaching was neither original nor especially profound, and concluded that most of its content had been borrowed from various Eastern and Western philosophies.[219] George Chryssides, on the other hand, found such descriptions of Rajneesh's teaching as a "potpourri" of various religious teachings unfortunate because Rajneesh was "no amateur philosopher". Drawing attention to Rajneesh's academic background he stated that; "Whether or not one accepts his teachings, he was no charlatan when it came to expounding the ideas of others."[275] He described Rajneesh as primarily a Buddhist teacher, promoting an independent form of "Beat Zen"[275] and viewed the unsystematic, contradictory and outrageous aspects of Rajneesh's teachings as seeking to induce a change in people, not as philosophy lectures aimed at intellectual understanding of the subject.[275]

Similarly with respect to Rajneesh's embracing of Western counter-culture and the human potential movement, though Mullan acknowledged that Rajneesh's range and imagination were second to none,[281] and that many of his statements were quite insightful and moving, perhaps even profound at times,[282] he perceived "a potpourri of counter-culturalist and post-counter-culturalist ideas" focusing on love and freedom, the need to live for the moment, the importance of self, the feeling of "being okay", the mysteriousness of life, the fun ethic, the individual's responsibility for their own destiny, and the need to drop the ego, along with fear and guilt.[283] Mehta notes that Rajneesh's appeal to his Western disciples was based on his social experiments, which established a philosophical connection between the Eastern guru tradition and the Western growth movement.[274] He saw this as a marketing strategy to meet the desires of his audience.[219] Urban, too, viewed Rajneesh as negating a dichotomy between spiritual and material desires, reflecting the preoccupation with the body and sexuality characteristic of late capitalist consumer culture and in tune with the socio-economic conditions of his time.[284]

The British professor of religious studies Peter B. Clarke said that most participators felt they had made progress in self-actualisation as defined by American psychologist Abraham Maslow and the human potential movement.[86] He stated that the style of therapy Rajneesh devised, with its liberal attitude towards sexuality as a sacred part of life, had proved influential among other therapy practitioners and new age groups.[285] Yet Clarke believes that the main motivation of seekers joining the movement was "neither therapy nor sex, but the prospect of becoming enlightened, in the classical Buddhist sense".[86]

In 2005, Urban observed that Rajneesh had undergone a "remarkable apotheosis" after his return to India, and especially in the years since his death, going on to describe him as a powerful illustration of what F. Max Müller, over a century ago, called "that world-wide circle through which, like an electric current, Oriental thought could run to the West and Western thought return to the East".[284] Clarke also said that Rajneesh has come to be "seen as an important teacher within India itself" who is "increasingly recognised as a major spiritual teacher of the twentieth century, at the forefront of the current 'world-accepting' trend of spirituality based on self-development".[285]

Appraisal as charismatic leader

A number of commentators have remarked upon Rajneesh's charisma. Comparing Rajneesh with Gurdjieff, Anthony Storr wrote that Rajneesh was "personally extremely impressive", noting that "many of those who visited him for the first time felt that their most intimate feelings were instantly understood, that they were accepted and unequivocally welcomed rather than judged. [Rajneesh] seemed to radiate energy and to awaken hidden possibilities in those who came into contact with him".[286] Many sannyasins have stated that hearing Rajneesh speak, they "fell in love with him".[287][288] Susan J. Palmer noted that even critics attested to the power of his presence.[287] James S. Gordon, a psychiatrist and researcher, recalls inexplicably finding himself laughing like a child, hugging strangers and having tears of gratitude in his eyes after a glance by Rajneesh from within his passing Rolls-Royce.[289] Frances FitzGerald concluded upon listening to Rajneesh in person that he was a brilliant lecturer, and expressed surprise at his talent as a comedian, which had not been apparent from reading his books, as well as the hypnotic quality of his talks, which had a profound effect on his audience.[290] Hugh Milne (Swami Shivamurti), an ex-devotee who between 1973 and 1982 worked closely with Rajneesh as leader of the Poona Ashram Guard[291] and as his personal bodyguard,[292][293] noted that their first meeting left him with a sense that far more than words had passed between them: "There is no invasion of privacy, no alarm, but it is as if his soul is slowly slipping inside mine, and in a split second transferring vital information."[294] Milne also observed another facet of Rajneesh's charismatic ability in stating that he was "a brilliant manipulator of the unquestioning disciple".[295]

Hugh B. Urban said that Rajneesh appeared to fit with Max Weber's classical image of the charismatic figure, being held to possess "an extraordinary supernatural power or 'grace', which was essentially irrational and affective".[296] Rajneesh corresponded to Weber's pure charismatic type in rejecting all rational laws and institutions and claiming to subvert all hierarchical authority, though Urban said that the promise of absolute freedom inherent in this resulted in bureaucratic organisation and institutional control within larger communes.[296]

Some scholars have suggested that Rajneesh may have had a narcissistic personality.[297][298][299] In his paper The Narcissistic Guru: A Profile of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, Ronald O. Clarke, Emeritus Professor of Religious Studies at Oregon State University, argued that Rajneesh exhibited all the typical features of narcissistic personality disorder, such as a grandiose sense of self-importance and uniqueness; a preoccupation with fantasies of unlimited success; a need for constant attention and admiration; a set of characteristic responses to threats to self-esteem; disturbances in interpersonal relationships; a preoccupation with personal grooming combined with frequent resorting to prevarication or outright lying; and a lack of empathy.[299] Drawing on Rajneesh's reminiscences of his childhood in his book Glimpses of a Golden Childhood, he suggested that Rajneesh suffered from a fundamental lack of parental discipline, due to his growing up in the care of overindulgent grandparents.[299] Rajneesh's self-avowed Buddha status, he concluded, was part of a delusional system associated with his narcissistic personality disorder; a condition of ego-inflation rather than egolessness.[299]

Wider appraisal as a thinker and speaker

There are widely divergent assessments of Rajneesh's qualities as a thinker and speaker. Khushwant Singh, an eminent author, historian, and former editor of the Hindustan Times, has described Rajneesh as "the most original thinker that India has produced: the most erudite, the most clearheaded and the most innovative".[300] Singh believes that Rajneesh was a "free-thinking agnostic" who had the ability to explain the most abstract concepts in simple language, illustrated with witty anecdotes, who mocked gods, prophets, scriptures, and religious practices, and gave a totally new dimension to religion.[301] German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, a one-time devotee of Rajneesh's (living at the Pune ashram from 1978 to 1980), described him as a "Wittgenstein of religions", ranking him as one of the greatest figures of the 20th century; in his view, Rajneesh had performed a radical deconstruction of the word games played by the world's religions.[302][303]

During the early 1980s, a number of commentators in the popular press were dismissive of Rajneesh.[304] The Australian critic Clive James scornfully referred to him as "Bagwash", likening the experience of listening to one of his discourses to sitting in a laundrette and watching "your tattered underwear revolve soggily for hours while exuding grey suds. The Bagwash talks the way that he looks."[304][305] James finished by saying that Rajneesh, though a "fairly benign example of his type", was a "rebarbative dingbat who manipulates the manipulable into manipulating one another".[304][305][306] Responding to an enthusiastic review of Rajneesh's talks by Bernard Levin in The Times, Dominik Wujastyk, also writing in The Times, similarly expressed his opinion that the talk he heard while visiting the Puna ashram was of a very low standard, wearyingly repetitive and often factually wrong, and stated that he felt disturbed by the personality cult surrounding Rajneesh.[304][307]

Writing in the Seattle Post Intelligencer in January 1990, American author Tom Robbins stated that based on his readings of Rajneesh's books, he was convinced Rajneesh was the 20th century's "greatest spiritual teacher". Robbins, while stressing that he was not a disciple, further stated that he had "read enough vicious propaganda and slanted reports to suspect that he was one of the most maligned figures in history".[300] Rajneesh's commentary on the Sikh scripture known as Japuji was hailed as the best available by Giani Zail Singh, the former President of India.[255] In 2011, author Farrukh Dhondy reported that film star Kabir Bedi was a fan of Rajneesh, and viewed Rajneesh's works as "the most sublime interpretations of Indian philosophy that he had come across". Dhondy himself said Rajneesh was "the cleverest intellectual confidence trickster that India has produced. His output of the 'interpretation' of Indian texts is specifically slanted towards a generation of disillusioned westerners who wanted (and perhaps still want) to 'have their cake, eat it' [and] claim at the same time that cake-eating is the highest virtue according to ancient-fused-with-scientific wisdom."[308]

Films about Rajneesh

- 1974: The first documentary film about Rajneesh was made by David M. Knipe. Program 13 of Exploring the Religions of South Asia, A Contemporary Guru: Rajneesh. (Madison: WHA-TV 1974)

- 1978: The second documentary on Rajneesh called Bhagwan, The Movie[309] was made in 1978 by American filmmaker Robert Hillmann.

- 1979: In 1978 the German film maker Wolfgang Dobrowolny (Sw Veet Artho) visited the Ashram in Poona and created a unique documentary about Rajneesh, his Sannyasins and the ashram, titled Ashram in Poona: Bhagwans Experiment.[310][311]

- 1981: In 1981, the BBC broadcast an episode in the documentary series The World About Us titled The God that Fled, made by British American journalist Christopher Hitchens.[305][312]

- 1985 (3 November): CBS News' 60 Minutes aired a segment about the Bhagwan in Oregon.

- 1987: In the mid-eighties Jeremiah Films produced a film Fear is the Master.[313]

- 1989: Another documentary, named Rajneesh: Spiritual Terrorist, was made by Australian film maker Cynthia Connop in the late 1980s for ABC TV/Learning Channel.[314]

- 1989: UK documentary series called Scandal produced an episode entitled, "Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh: The Man Who Was God".[315]

- 2002: Forensic Files Season 7 Episode 8 takes a look in to how forensics was used to determine the cause of the bio-attack in 1984.

- 2010: A Swiss documentary, titled Guru – Bhagwan, His Secretary & His Bodyguard, was released in 2010.[316]

- 2012: Oregon Public Broadcasting produced the documentary titled Rajneeshpuram which aired 19 November 2012.[317]

- 2016: Rebellious Flower, an Indian-made biographical movie of Rajneesh's early life, based upon his own recollections and those of those who knew him, was released. It was written and produced by Jagdish Bharti and directed by Krishan Hooda, with Prince Shah and Shashank Singh playing the title role.[318]

- 2018: Wild Wild Country, a Netflix documentary series on Rajneesh, focusing on Rajneeshpuram and the controversies surrounding it.[319]

Selected discourses

On the sayings of Jesus:

- The Mustard Seed (the Gospel of Thomas)

- Come Follow Me Vols. I – IV

On Tao:

- Tao: The Three Treasures (The Tao Te Ching of Lao Tzu), Vol I – IV

- The Empty Boat (Stories of Chuang Tzu)

- When the Shoe Fits (Stories of Chuang Tzu)

On Gautama Buddha:

- The Dhammapada (Vols. I – X)

- The Discipline of Transcendence (Vols. I – IV)

- The Heart Sutra

- The Diamond Sutra

On Zen:

- Neither This nor That (On the Xin Xin Ming of Sosan)

- No Water, No Moon

- Returning to the Source

- And the Flowers Showered

- The Grass Grows by Itself

- Nirvana: The Last Nightmare

- The Search (on the Ten Bulls)

- Dang dang doko dang

- Ancient Music in the Pines

- A Sudden Clash of Thunder

- Zen: The Path of Paradox

- This Very Body the Buddha (on Hakuin's Song of Meditation)

On the Baul mystics:

- The Beloved

On Sufis:

- Until You Die

- Just Like That

- Unio Mystica Vols. I and II (on the poetry of Sanai)

On Hassidism:

- The True Sage

- The Art of Dying

On the Upanishads:

- I am That – Talks on Isha Upanishad

- The Supreme Doctrine

- The Ultimate Alchemy Vols. I and II

- Vedanta: Seven Steps to Samadhi

On Heraclitus:

- The Hidden Harmony

On Kabir:

- Ecstasy: The Forgotten Language

- The Divine Melody

- The Path of Love

On Buddhist Tantra:

- Tantra: The Supreme Understanding

- The Tantra Vision

- Yoga: The Alpha and the Omega Vols. I – X

(reprinted as Yoga, the Science of the Soul)

On Meditation methods:

- The Book of Secrets, Vols. I – V

- Meditation: the Art of Inner Ecstasy

- The Orange Book

- Meditation: The First and Last Freedom

- Learning to Silence the Mind

On his childhood:

- Glimpses of a Golden Childhood

On Guru Nanak's Japji and Sikhism:

- The True Name