Chatsworth House

| Chatsworth House | |

|---|---|

The River Derwent, bridge and house at Chatsworth | |

| General information | |

| Type | House |

| Architectural style | English Baroque, Italianate |

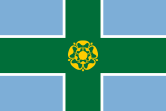

| Location | near Bakewell, Derbyshire |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 53°13′40″N 1°36′36″W / 53.22778°N 1.61000°W |

| Elevation | 125 m (410 ft) |

| Construction started | 1687 |

| Completed | 1708, with additions 1820–1840 |

| Owner | Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement, who lease the house to the Chatsworth House Trust. |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 5 |

| Floor area | Main house (excluding wing): approx 81,000 sq ft |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | William Talman Thomas Archer Jeffry Wyattville Joseph Paxton James Paine |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | Approx 300 |

| Website | |

| www | |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Chatsworth House |

| Designated | 29 September 1951 |

| Reference no. | 1373871[1] |

Chatsworth House is a stately home in the Derbyshire Dales, 4 miles (6.4 km) north-east of Bakewell and 9 miles (14 km) west of Chesterfield, England. The seat of the Duke of Devonshire, it has belonged to the Cavendish family since 1549. It stands on the east bank of the River Derwent, across from hills between the Derwent and Wye valleys, amid parkland backed by wooded hills that rise to heather moorland.

The house holds major collections of paintings, furniture, Old Master drawings, neoclassical sculptures and books. Chosen several times as Britain's favourite country house,[2][3] it is a Grade I listed property from the 17th century, altered in the 18th and 19th centuries.[1] In 2011–2012 it underwent a £14-million restoration.[4] The owner is the Chatsworth House Trust, an independent charitable foundation formed in 1981, on behalf of the Cavendish family.[5]

History[edit]

11th–16th centuries[edit]

The name 'Chatsworth' is a corruption of Chetel's-worth, meaning "the Court of Chetel".[6] In the reign of Edward the Confessor, a man of Norse origin named Chetel held lands jointly with a Saxon named Leotnoth in three townships: Ednesoure to the west of the Derwent, and Langoleie and Chetesuorde to the east.[7] Chetel was deposed after the Norman Conquest, and in the Domesday Book of 1086 the Manor of Chetesuorde is listed as the property of the Crown in the custody of William de Peverel.[6] Chatsworth ceased to be a large estate, until the 15th century when it was acquired by the Leche family who owned property nearby. They enclosed the first park at Chatsworth and built a house on the high ground in what is now the south-eastern part of the garden. In 1549 they sold all their property in the area to Sir William Cavendish, Treasurer of the King's Chamber and the husband of Bess of Hardwick, who had persuaded him to sell his property in Suffolk and settle in her native county.

Bess began to build the new house in 1553. She selected a site near the river, which was drained by digging a series of reservoirs, which doubled as fish ponds. Sir William died in 1557, but Bess finished the house in the 1560s and lived there with her fourth husband, George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury. In 1568 Shrewsbury was entrusted with the custody of Mary, Queen of Scots, and brought his prisoner to Chatsworth several times from 1570 onwards. She lodged in the apartment now known as the Queen of Scots rooms, on the top floor above the great hall, which faces onto the inner courtyard. An accomplished needlewoman, Bess joined Mary at Chatsworth for extended periods in 1569, 1570, and 1571, during which time they worked together on the Oxburgh Hangings.[8] Bess died in 1608 and Chatsworth was passed to her eldest son, Henry. The estate was purchased from Henry by his brother William Cavendish, 1st Earl of Devonshire, for £10,000.

17th century[edit]

Few changes were made at Chatsworth until the mid-17th century. William Cavendish, 3rd Earl of Devonshire, was a staunch Royalist, expelled from the House of Lords in 1642. He left England for the safety of the continent and his estates were sequestered.[9] Chatsworth was occupied by both sides during the Civil War, and the 3rd Earl did not return to the house until The Restoration of the monarchy. He reconstructed the principal rooms in an attempt to make them more comfortable, but the Elizabethan house was outdated and unsafe.

The famed political philosopher Thomas Hobbes spent the last four or five years of his life at Chatsworth Hall, then owned by William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Devonshire. He had been a friend of the family for nearly 70 years, having taken a job tutoring the 2nd Earl shortly after graduating from St John's College, Cambridge in 1608.[10] Hobbes died at another Cavendish family estate, Hardwick Hall, in December 1679. After his death, many of Hobbes' manuscripts were found at Chatsworth House.[11]

William Cavendish, 4th Earl of Devonshire, who became the 1st Duke in 1694 for helping to put William of Orange on the English throne, was an advanced Whig. He was forced to retire to Chatsworth during the reign of King James II. This called for rebuilding the house, which began in 1687. Cavendish aimed initially to reconstruct only the south wing with the State Apartments and so decided to retain the Elizabethan courtyard plan, although its layout was becoming increasingly unfashionable. He enjoyed building and reconstructed the East Front, which included the Painted Hall and Long Gallery, followed by the West Front from 1699 to 1702. The North Front was completed in 1707 just before he died. The 1st Duke also had large parterre gardens designed by George London and Henry Wise, who was later appointed by Queen Anne as Royal Gardener at Kensington Palace.

18th century[edit]

William Cavendish, 2nd Duke of Devonshire, and William Cavendish, 3rd Duke of Devonshire, made no changes to the house or gardens, but both contributed much to the collection found at Chatsworth at the time. Connoisseurs of the arts, they included in the collection paintings, Old Master drawings and prints, ancient coins and carved Greek and Roman sculptures. Palladian furniture designed by William Kent was commissioned by the 3rd Duke when he had Devonshire House in London rebuilt after a fire in 1733. When Devonshire House was sold and demolished in 1924, the furniture was transferred to Chatsworth.

The 4th Duke made great changes to the house and gardens. He decided the approach to the house should be from the west. He had the old stables and offices as well as parts of Edensor village pulled down so they were not visible from the house, and replaced the 1st Duke's formal gardens with a more natural look, designed by Capability Brown, which he helped bring into fashion.

In 1748, the 4th Duke married Lady Charlotte Boyle, the sole surviving heiress of Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington. Lord Burlington was an accomplished architect in his own right with many works to his name including Chiswick House. With his death, his important collection of architectural drawings and Inigo Jones masque designs, Old Master paintings and William Kent-designed furniture were transferred to the Dukes of Devonshire. This inheritance also brought many estates to the family.

In 1774, William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire, married Georgiana Spencer famous as a socialite who gathered around her a large circle of literary and political friends. Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds would paint her; the Gainsborough painting would be disposed of by the 5th Duke and be recovered much later, after many vicissitudes. The film The Duchess portrayed their life together. Georgiana was the great-great-great-great aunt of Diana, Princess of Wales; their lives, centuries apart, have been compared in tragedy.[12]

19th century[edit]

The 6th Duke (known as "the Bachelor Duke") was a passionate traveller, builder, gardener and collector, who transformed Chatsworth. In 1811 he inherited the title and eight major estates: Chatsworth and Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, Devonshire House, Burlington House and Chiswick House in London, Bolton Abbey and Londesborough Hall in Yorkshire, and Lismore Castle in Ireland. These covered 200,000 acres (810 km2) of land in England and Ireland.

The Duke was a collector especially of sculpture and books. When he built the North Wing to the designs of Sir Jeffry Wyatville, it included a purpose-built Sculpture Gallery to house his collection. He took over several rooms in the house to contain the entire libraries he was purchasing at auction. The 6th Duke loved to entertain, and the early 19th century saw a rise in popularity of country-house parties. In addition to a sculpture gallery, the new north wing housed an orangery, a theatre, a Turkish bath, a dairy, a vast new kitchen and numerous servants rooms. In 1830 the Duke increased the guest accommodation by converting suites of rooms into individual guest bedrooms. People invited to stay at Chatsworth spent their days hunting, riding, reading and playing billiards. In the evening formal dinners would take place, followed by music, charades and billiards or conversation in the smoking room for the men. Women would return to their bedroom many times during the day to change their outfits. The guest bedrooms on the east front at Chatsworth are the most complete set from the period to survive with their original furnishings.[13]: 52 There is much eastern influence in the decoration, including hand-painted Chinese wallpapers and fabrics typical of Regency taste, which developed in the reign of George IV (1762–1830). Those who stayed at Chatsworth included Queen Victoria and Charles Dickens.

In October 1832, Princess Victoria (later Queen Victoria) and her mother, the Duchess of Kent, visited Chatsworth, where the Princess had her first formal adult dinner at the age of 13, in the new dining room. The 6th Duke had another chance to welcome Victoria in 1843, when the Queen and Prince Albert returned to enjoy an array of illumination in the gardens, in the conservatory and on the fountains, forming a scene of "unparalleled display and grandeur", according to one guest.[14]

The Duke spent 47 years transforming the house and gardens. A Latin inscription over the fireplace in the Painted Hall translates, "William Spencer, Duke of Devonshire, inherited this most beautiful house from his father in the year 1811, which had been begun in the year of English liberty 1688, and completed it in the year of his bereavement 1840." The year 1688 was that of the Glorious Revolution, supported by the Whig dynasties including the Cavendishes. The year 1840 brought the death of the Duke's beloved niece Blanche, who was married to his heir, the future 7th Duke.

In 1844, the 6th Duke privately printed and published a book called Handbook to Chatsworth and Hardwick, giving a history of the Cavendish family's two main estates. It was praised by Charles Dickens.[15][16]

20th century[edit]

Social change and taxes in the early 20th century began to affect the Devonshires' lifestyle. When the 8th Duke died in 1908 over £500,000 of death duties became due. This was a small charge compared with that of 42 years later, but the estate was already burdened with debt from the 6th Duke's extravagances, the failure of the 7th Duke's business ventures at Barrow-in-Furness, and the depression in British agriculture apparent since the 1870s. In 1912 the family sold 25 books printed by William Caxton and a collection of 1,347 volumes of plays acquired by the 6th Duke, including four Shakespeare folios and 39 Shakespeare quartos, to the Huntington Library in California. Tens of thousands of acres of land in Somerset, Sussex and Derbyshire were also sold during or just after the First World War.

In December 1904, King Charles I of Portugal and Queen Maria Amélia stayed at Chatsworth House during their visit to Britain. It snowed almost constantly while they were there and the King reportedly started a snowball fight, in which the assembled ladies joined enthusiastically, when he met the Marquis of Soveral, the Portuguese Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Court of St James's.[17]

In 1920 the family's London mansion, Devonshire House, which occupied a 3-acre (12,000 m2) site in Piccadilly, was sold to developers and demolished. Much of its contents went to Chatsworth and a much smaller house at 2 Carlton Gardens near The Mall was acquired. The Great Conservatory in the garden at Chatsworth was demolished, as it needed 10 men to run it, huge quantities of coal to heat it and all the plants had died during the war, when no coal had been available for non-essential purposes. To reduce running costs further, there was talk of pulling down the 6th Duke's north wing, which was then seen as having no aesthetic or historical value, but nothing came of it. Chiswick House – the celebrated Palladian villa in the suburbs of West London that the Devonshires inherited when the 4th Duke married Lord Burlington's daughter – was sold in 1929 for £80,000 to Middlesex County Council and Brentford and Chiswick Urban District Council.[18]

Nonetheless, life at Chatsworth continued much as before. The household was run by a comptroller and domestic staff were still available, although more so in the countryside than the cities. The staff at Chatsworth at the time consisted of a butler, an under-butler, a groom of the chambers, a valet, three footmen, a housekeeper, the Duchess's maid, 11 housemaids, two sewing women, a cook, two kitchen maids, a vegetable maid, two or three scullery maids, two still-room maids, a dairy maid, six laundry maids and the Duchess's secretary. All these 38 or 39 people lived in the house. Daily staff included the odd man, an upholsterer, a scullery maid, two scrubbing women, a laundry porter, a steam boiler man, a coal man, two porter's lodge attendants, two night firemen, a night porter, two window cleaners, and a team of joiners, plumbers and electricians. The Clerk of Works supervised the maintenance of the house and other properties on the estate. There were also grooms, chauffeurs and gamekeepers. The number of garden staff was somewhere between 80 in the 6th Duke's time and the 20 or so in the early 21st century. There was also a librarian, Francis Thompson, who wrote the first book-length account of Chatsworth since the 6th Duke's handbook.[citation needed]

Most of the UK's country houses were put to institutional use in the Second World War. Some of those used as barracks were badly damaged, but the 10th Duke, thinking that schoolgirls would make better tenants than soldiers, arranged for Chatsworth to be occupied by Penrhos College, a girls' public school in Colwyn Bay, Wales. The contents were packed away in 11 days, and in September 1939, 300 girls and their mistresses moved in for a six-year stay. The whole house was used, including the state rooms, which were turned into dormitories. Condensation from the breath of the sleeping girls caused fungus to grow behind some of the pictures. The house was not very comfortable for so many people, with a shortage of hot water, but there were compensations, such as skating on the Canal Pond. The girls grew vegetables in the garden as a contribution to the war effort.[citation needed]

In May 1944 Kathleen Kennedy, sister of John F. Kennedy, married William Cavendish, Marquess of Hartington, elder son of the 10th Duke of Devonshire. However, he was killed in action in Belgium in September 1944 and Kathleen died in a plane crash in 1948. His younger brother Andrew became the 11th Duke in 1950. He was married to Deborah Mitford, one of the Mitford girls, sister to Nancy Mitford, Diana Mitford, Pamela Mitford, Unity Mitford and Jessica Mitford.

The modern history of Chatsworth begins in 1950. The family had yet to move back after the war. Although the 10th Duke had transferred his assets to his son during his lifetime in the hope of avoiding death duties, the Duke died a few weeks too early for the lifetime exemption to apply and tax was charged at 80 per cent on the estate. The amount due was £7 million (£255 million as of 2021)[19]. Some of the family's advisors considered the situation irretrievable and there was a proposal to transfer Chatsworth to the nation as a Victoria and Albert Museum of Northern England. Instead, the Duke decided to retain his family's home if he could. He sold tens of thousands of acres of land, transferred Hardwick Hall to the National Trust in lieu of tax, and sold some major works of art from Chatsworth. The family's Sussex house, Compton Place was lent to a school.

The effect of the death duties was mitigated to an extent by the historically low value of art in the post-war years and the increase in land values after 1950, during the post-war agricultural revival, and so on the face of it the losses were much less than 80 per cent in terms of physical assets. In Derbyshire 35,000 acres (140 km2) were retained out of 83,000 acres (340 km2). The Bolton Abbey estate in Yorkshire and the Lismore Castle estate in Ireland remained in the family. It took 17 years to complete negotiations with the Inland Revenue, interest being due in the meantime. The Chatsworth Estate is now managed by the Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement, established in 1946.[citation needed]

The 10th Duke was pessimistic about the future of houses like Chatsworth and made no plans to move back in after the war. After Penrhos College left in 1945, the only people who slept in the house were two housemaids, but over the winter of 1948–1949 the house was cleaned and tidied for reopening to the public by two Hungarian women, who had been Kathleen Kennedy's cook and housemaid in London, and a team of their compatriots. The house was Grade I listed in 1951 after the passage of the Town and Country Planning Act 1947.[1]

In the mid-1950s, the 11th Duke and Duchess began to think about moving in. The pre-war house had relied wholly on a large staff for its comforts, and lacked modern facilities. The building was rewired, the plumbing and heating were overhauled, and six self-contained staff flats created to replace the small staff bedrooms and communal servants' hall. Including those in the staff flats, 17 bathrooms were added to the existing handful. The 6th Duke's cavernous kitchen was abandoned and a new one was created closer to the family dining room. The family rooms were repainted, carpets were brought out of store and curtains were repaired or replaced. The Duke and Duchess and their three children moved across the park from Edensor House in 1959.

In 1981, the trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement, owners of the house, created a new Chatsworth House Trust. The aim was to preserve the house and its setting for "the benefit of the public".[20] The new trust was granted a 99-year lease of the house, its main contents, its grounds, its precincts and adjacent forestry, a total of 1,822 acres (7.37 km2). To legalise this, the Chatsworth House Trust pays a token rent of £1 a year. To facilitate the arrangement and build up a sufficient multi-million-pound endowment fund, the trustees sold works of art, mostly old masters' drawings, which had not been on regular display. The Cavendish family is represented on the House Trust's Council of Management, but most of the directors are not family members. The Duke pays a market rent for use of his private apartments in the house. The cost of running the house and grounds is about £4 million a year.[citation needed]

Film of Chatsworth in 1945 is held by the Cinema Museum in London. Ref HM0365.[21]

21st century[edit]

The 11th Duke died in 2004 and was succeeded by his son, the current Duke, Peregrine Cavendish, 12th Duke of Devonshire. The 11th Duke's widow, the Dowager Duchess of Devonshire, died on 24 September 2014. Until then she was active in promoting the estate and increasing its visitor income. She made many additions to the gardens, including the maze, the kitchen, the cottage gardens and several commissions of modern sculpture. As Deborah Mitford, she wrote seven books on various aspects of Chatsworth and its massive property.[22]

A structural survey in 2004 showed that major renovation was required. A £32 million programme of works was undertaken, including restoration of stonework, statues, paintings, tapestries and water features. The work, the most extensive for 200 years, took ten years and was completed in 2018.[23]

According to the Estate website, Chatsworth remains home to the 12th Duke and Duchess. They are involved in the operation through the Charitable Trust.[24]

The Devonshire Collection Archives stored at Chatsworth include 450 years of documents about the family and their two main estates.[25] In 2019, the Duke and Duchess visited Sotheby's to view "Treasures From Chatsworth: art and artifacts from Chatsworth House" that would be displayed in New York.[26][27]

During the 2022 European heatwaves, a section of the Great Parterre that formerly occupied Chatsworth's South Lawn was revealed as the grass and soil dried out, showing the patterns of earthworks that had been used to construct it. As the lawn's grass has shorter roots, it dried out faster, creating a contrast that allows the structure to be viewed with the naked eye.[28][29]

Architecture[edit]

Chatsworth House is built on sloping ground, lower on the north and west sides than on the south and east sides. The original Tudor mansion was built in the 1560s by Bess of Hardwick in a quadrangle layout, about 170 feet (50 m) from north to south and 190 feet (60 m) from east to west, with a large central courtyard. The main entrance was on the west front, which was embellished with four towers or turrets, and the great hall in the medieval tradition was on the east side of the courtyard, where the Painted Hall remains the focus of the house to this day.

The south and east fronts were rebuilt to the designs of William Talman and completed by 1696 for William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Devonshire. The 1st Duke's Chatsworth was a key building in the development of English Baroque architecture. According to the architectural historian Sir John Summerson, "It inaugurates an artistic revolution which is the counterpart of the political revolution in which the Earl was so prominent a leader." The design of the south front was revolutionary for an English house, with no attics or hipped roof, but instead two main stories supported by a rustic basement. The façade is dramatic and sculptural with ionic pilasters and a heavy entablature and balustrade. The existing heavy and angular stone stairs from the first floor down to the garden are a 19th-century replacement of an elegant curved double staircase. The east front is the quietest of the four on the main block. Like the south front it is unusual in having an even number of bays and no centrepiece. The emphasis is placed on the end bays, each highlighted by double pairs of pilasters, of which the inner pairs project outwards.

The west and north fronts may have been the work of Thomas Archer, possibly in collaboration with the Duke himself. The west front has nine wide bays with a central pediment supported by four columns and pilasters to the other bays. Due to the slope of the site, this front is taller than the south front. It is also large, with many other nine-bay three-storey façades little more than half as wide and tall. The west front is very lively with much carved stonework, and the window frames are highlighted with gold leaf, which catches the setting sun. The north front was the last to be built. It presented a challenge, as the north end of the west front projected nine feet (3 m) further than the north end of the east front. The problem was overcome by building a slightly curved façade to distract the eye. The attic windows on this side are the only ones visible on the exterior of the house and are set into the main façade, rather than into a visible roof. Those in the curved section were originally oval, but are now rectangular like those in the end sections. The north front was altered in the 19th century, when William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire, and the architect Jeffry Wyatville, built the North Wing, doubling the size of the house. Most of the wing has only two storeys, as opposed to the three of the main block. It is attached to the north-east corner of the house and around 400 feet (120 m) long. At the end of the North Wing is the North, or Belvedere, Tower. The work was carried out in an Italianate style that blends smoothly with the elaborate finish of the baroque house.[citation needed]

The 6th Duke built a gatehouse at this end of the house with three gates. The central, largest gate led to the North Entrance, then the main entrance to the house. This is now the entrance used by visitors. The north gate led to the service courtyard, while the matching south gate led to the original front door in the west front, which was relegated to secondary status in the Duke's time, but is now the family's private entrance again.

The façades of the central courtyard were also rebuilt by the 1st Duke. The courtyard was larger than it is now, as there were no corridors on the western side and the northern and southern sides only had enclosed galleries on the first floor, with open galleries below. In the 19th century, new accommodation was built on these three sides on all three levels. The only surviving baroque façade is that on the eastern side, where five bays of the original seven remain, and are largely as built. There are carved trophies by Samuel Watson, a Derbyshire craftsman who did much work at Chatsworth in stone, marble and wood.

Interiors[edit]

The 1st and 6th Dukes both inherited an old house and tried to adapt to the lifestyle of their time without changing the fundamental layout, which in this way is unique, full of irregularities, and the interiors are decorated by a diverse centuries-old collection of different styles. Many of the rooms are recognisable as of one main period, but in nearly every case, they have been altered more often than might be supposed at first glance.

State apartments[edit]

The 1st Duke created a richly appointed Baroque suite of state rooms across the south front when expecting a visit from King William III and Queen Mary II, which never occurred. The State Apartments are approached from the Painted Hall, decorated with murals of scenes from the life of Julius Caesar by Louis Laguerre, and ascend by the cantilevered Great Stairs to an enfilade of rooms that controlled how far a person could progress into the presence of the King and Queen.

The Great Chamber is the largest in the State Apartments, followed by the State Drawing Room, the Second Withdrawing Room, the State Bedroom and finally the State Closet, each room being more private and ornate than the last. The Great Chamber has a painted ceiling of a classical scene by Antonio Verrio.[30] The Second Withdrawing Room was renamed the State Music Room when the 6th Duke brought the violin door from Devonshire House in London. It has a convincing trompe-l'œil of a violin and bow "hanging" on a silver knob, painted about 1723 by Jan van der Vaart.[31][32]

About the time Queen Victoria decided that Hampton Court, with state apartments in the same style, was uninhabitable, the 6th Duke wrote that he was tempted to demolish the State Apartments to make way for new bedrooms. However, sensitive to his family heritage, he left the rooms largely untouched, making additions rather than changing the existing spaces of the house. Changes to the main baroque interiors were restricted to details such as stamped leather hangings on the walls of the State Music Room and State Bedroom, and a wider, shallower, but less elegant staircase in the Painted Hall, which was itself later replaced. The contents of the State Apartments were rearranged in 2010 to reflect the way they had looked in the 17th and 18th centuries.[33]

18th-century alterations[edit]

In the 1760s, William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, redirected the approach to Chatsworth. He converted the kitchen in the centre of the north front into an entrance hall, from which guests walked through an open colonnade in the courtyard, through a passage past the cook's bedroom and the back stairs, and into the Painted Hall. He then built a neoclassical service wing for his kitchens that was a forerunner of the 6th Duke's north wing. William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire, had some of the family's private rooms redecorated and some partition walls moved, but there are few traces of the mid and late 18th century in the public rooms.

19th-century alterations[edit]

The 6th Duke modified much of Chatsworth to meet 19th-century standards of comfort, suiting a less formal lifestyle than that of the 1st Duke's time. The corridors round the courtyard were enclosed and given a multicoloured marble floor, so that rooms could be easily reached from indoors, and there were more shared living rooms to replace individual guest apartments. The cook's bedroom and the back stairs made way for the Oak Stairs, topped by a glass dome and built at the north end of the Painted Hall to improve internal communications. Along the staircase hang portraits of the first 11 Dukes and some of their family members. The Duke made a library of the long gallery, originally created by the 1st Duke. He was a great lover of books and purchased entire libraries. The Ante-Library in the adjoining room was originally used by the 1st Duke as a dining room and then a billiard room, before the 6th Duke used it for his growing collection of books. This was just one of the rooms where the Duke installed a single-pane window, which he saw as the "greatest ornament of modern decoration".[13] The window in the Ante-Library is the only one preserved. Much of the scientific library of Henry Cavendish (1731–1810) is in this room. The most notable addition by the 6th Duke to Chatsworth was the Wyatville-designed North Wing. Plans for a symmetrical wing to the south were begun, but later abandoned.[13]

The entire ground floor of the North Wing was occupied by service rooms, including a kitchen, servants' hall, laundry, butler and housekeeper's rooms. On the first floor, facing west, were two sets of bachelor bedrooms called "California" and "The Birds". The main rooms in the new wing face east and were accessed from the main house through a small library called the Dome Room. The first room beyond is a dining room, with a music gallery in the serving lobby where the musicians played. Next is the sculpture gallery, the largest room in the house, and then the orangery. The Belvedere Tower contains a plunge bath, using marble from the 1st Duke's bathroom, and a ballroom that was later turned into a theatre by the 8th Duke. Above the theatre is the belvedere itself, an open viewing platform below the roof.

Private rooms[edit]

Chatsworth has 126 rooms, with nearly 100 of them closed to visitors. The house is well adapted to allow the family to live privately in their apartments while the house is open to the public. Deborah, Dowager Duchess of Devonshire, described the family rooms in detail in her book Chatsworth: The House. She lived at Edensor until her death in 2014; the present (12th) Duke and Duchess live at Chatsworth. The family occupies rooms on the ground and first floors of the south front, all three floors of the west front, and the upper two floors of the north front. Staircases in the north-east corner of the main block and in a turret in the east front enable them to move about without crossing the public route.

The main family living rooms are on the first floor of the south front. The family dining room is in the south-east corner and has the same dimensions as the State Dining Room directly above. This has been the usual location of the family dining room; the Bachelor Duke's dining room in the north wing took over that role for an interlude of little over a hundred years. Both Bess of Hardwick's house and the 1st Duke's house had a hierarchy of three dining rooms in this corner, each taller and more lavishly decorated than the one below. A common parlour on the ground floor was used by the gentlemen of the household, and later for informal family meals. Above it was the main family dining room, and at the top the Great Chamber, which was reserved for royalty, although the 6th Duke wrote that to his knowledge, it had never been used.

The yellow drawing room is next to the dining room and directly beneath the State Drawing Room. The Dowager Duchess wrote that the house is so solidly built that the crowds passing above are imperceptible. The trio of reception rooms here is completed by the blue drawing room, below the State Music Room. This was created in the 18th century by knocking together the 1st Duke's bedroom and dressing room, and has a door to his private gallery at the upper level of the chapel. It has also served as a billiard room and a school room. Charity events are sometimes held in this part of the house. Both drawing rooms have access to the garden through the South Front's external staircase.

Three corridors called the Tapestry Gallery, Burlington Corridor and Book Passage are wrapped round the south, west and north passages at this level and give access to family bedrooms. There is a sitting room in the north-west corner — one of the few rooms in the house with outside views in two directions. There are more family bedrooms on the second floor facing west and north. The Scots and Leicester bedrooms in the east wing are still used when there is a large house party, which is why they are sometimes available as a separately charged optional extra in the tour of the house and sometimes not. This suite now contains the 11th Duke's Exhibition. Visitors bypass the first floor on their way down the West Stairs from the state rooms to the chapel.

The private north stairs lead down to more private rooms on the ground floor of the West Front. In the centre is the West Entrance Hall, which is, once again, the family entrance. To the right on entering is a passage room known as the mineral room, which leads through to a study. To the left there is the Leather Room with walls of leather. Its great many books make it one of at least six libraries in the house. The next room is the Duke's Study, which has two windows, many more books and floral decoration painted for the Bachelor Duke by, in his own words, "three bearded artists in blouses imported from Paris". The corner room on the ground floor is the former "little dining room". These rooms are all very high, as the ground level in the west wing is lower than that of the Painted Hall and the ground floor corridors round the courtyard. Steps from the West Entrance Hall lead up to the west corridor.

The other family living rooms are in the eastern half of the ground floor of the South Front. They are reached through the Chapel Corridor on the public route or the turret staircase from the dining room. The room in the south-east corner was once the Ducal bathroom, until the Bachelor Duke built his new plunge bath in the North Wing, and is now a pantry where the family china is kept. This connects to the modern kitchen, which is under the library and made out of the steward's room and linen room. Next to the pantry in the south front are offices.

Park and landscape[edit]

The garden attracts about 300,000 visitors a year. It has a complex blend of features from six different centuries, covering 105 acres (0.42 km2). It is surrounded by a wall 1.75 miles (2.8 km) long. It sits on the eastern side of the valley of the Derwent River and blends into the surrounding park, which covers 1,000 acres (4.0 km2). The woods on the moors to the east of the valley form a backdrop to the garden. There is a staff of some 20 full-time gardeners. Average rainfall is some 33.7 inches (855 mm) a year, with an annual average of 1,160 hours of sunshine. Most of the main features of the garden were created in five main phases of development.

Elizabethan garden[edit]

The house and garden were first constructed by Sir William Cavendish and Bess of Hardwick in 1555. The Elizabethan garden was much smaller than the garden today. There were terraces to the east of the house where the main lawn is now, ponds and fountains to the south, and fishponds to the west by the river. The main visual remnant of the time is a squat stone tower known as Queen Mary's Bower on account of a legend that Mary, Queen of Scots was allowed to take the air there while a prisoner at Chatsworth. The bower is now outside the garden wall in the park. Some of the retaining walls of the West Garden also date from this era, but they were reconstructed and extended later.

1st Duke's garden (1684–1707)[edit]

While rebuilding the house, the 1st Duke also created Baroque gardens. It featured numerous parterres cut into the slopes above the house, and many fountains, garden buildings and classical sculptures. The main surviving features of that time are:

- The Cascade and Cascade House, a set of stone steps over which water flows from fountains at the top. It was built in 1696 and rebuilt more grandly in 1701. In 1703 a grand baroque Temple or Cascade House designed by Thomas Archer was added at the top. Major restoration of both in 1994–1996 took 10,000 man-hours of work. In 2004 the Cascade was voted England's best water feature by a panel of 45 garden experts chosen by Country Life.[34] It has 24 cut steps, each slightly different and with a variety of textures so that each gives a different sound when water runs over and down it.

- The Canal Pond dug in 1702 is a 314-yard (287 m)-long rectangular lake to the south of the house.

- The Seahorse Fountain is a sculptural fountain in a circular pond on the lawn between the house and the Canal Pond. Originally it was the centrepiece of the main parterre.

- The Willow Tree Fountain is an imitation tree that squirts water on the unsuspecting from its branches. The writer Celia Fiennes wrote in her diary: "There... in the middle of ye grove stands a fine willow tree, the leaves, barke and all looks very naturall, ye roote is full of rubbish or great stones to appearance and all on a sudden by ye turning of a sluice it rains from each leafe and from the branches like a shower, it being made of brass and pipes to each leafe, but in appearance is exactly like any willow." The tree has been replaced twice and then restored in 1983.

- The First Duke's greenhouse is a long, low building with ten arched windows and a temple-like centrepiece. It has been moved from a site overlooking the 1st Duke's bowling green to the northern edge of the main lawn and is now fronted by a rose garden.

- Flora's Temple is a classical edifice from 1695, moved to its present site at the northern end of the broad walk in 1760. It contains a statue of the goddess Flora by Caius Gabriel Cibber.

- The West Garden – now the family's private garden with modern planting in a three-section formal structure – is mainly a creation of the 1st Duke's time, but the layout is not original.

4th Duke's garden (1755–64)[edit]

The 4th Duke commissioned the landscape architect, Lancelot "Capability" Brown to transform the garden in the fashionable naturalistic landscape style of the day. Most of the ponds and parterres were turned into lawns, but as detailed above several features were spared. Many trees were planted, including various American species imported from Philadelphia in 1759. The main aim of the work was to improve integration of the garden and park. Brown's 5.5 acre (22,000 m2) Salisbury Lawns still form the setting of the Cascade.

6th Duke's garden (1826–58)[edit]

In 1826 a 23-year-old named Joseph Paxton, who had trained at Kew Gardens, was appointed head gardener at Chatsworth. The 6th Duke had inherited Chatsworth 15 years earlier and till then shown little interest in improving the neglected garden, but he soon formed a productive and extravagantly funded partnership with Paxton, who proved to be the most innovative garden designer of his era, and remains the greatest single influence on Chatsworth's garden. Features that survive from that time include:

- The Rockeries and The Strid: In 1842 Paxton began work on a rockery of a gargantuan scale, piling rocks weighing several tons one on top of another. One was described thus by Lord Desart in the 1860s: "In one place a sort of miniature Matterhorn apparently blocked the path but with the touch of the finger it revolved on a metal axis and made a way to pass." It is now locked in place to comply with health and safety regulations. Another rock is so balanced that it can be swayed with little pressure. Two rocks are named after the Queen and Prince Albert and another after the Duke of Wellington, all of whom visited Chatsworth in the 6th Duke's time. The Wellington Rock, a structure of several piled rocks, is 45 ft (14 m) high. A small waterfall drips over it into a pond. Sometimes in winter the water freezes, creating icicles. The water flows into a pond created by Paxton called 'The Strid', named after a stretch of the River Wharfe on the Devonshires' Bolton Abbey estate, where the river is pressed into a turbulent chasm just a yard wide. Chatsworth's Strid is a placid stretch of water fringed with rocks and luxuriant vegetation and crossed by a rustic bridge.

- The Arboretum and Pinetum: The 6th Duke's time was one of plant-hunting expeditions, with major new species readily discovered by intrepid botanists, and the Duke among the most generous sponsors. In 1829 he took an additional 8 acres (3.2 ha) of the park into the garden to create a pinetum, and in 1835 Paxton began work on an arboretum planned as a systematic succession of trees in accordance with botanical classification. Chatsworth has some of the oldest UK specimens of species such as Douglas fir and Giant Sequoia. Also in this part of the garden is the Grotto Pond, originally a fishpond, breeding fish for Chatsworth's table. The 6th Duke's mother had the rustic grotto built at the end of the 18th century. The area round the pond is now planted for autumn colour.

- The Azalea Dell and the Ravine: Rhododendrons and Azaleas grow well at Chatsworth as the soil suits them, and a section of the southern end of the garden is devoted to them. This is the most rugged part of the garden, with steep serpentine paths and a stream running down a valley known as The Ravine. In 1997 a waterfall was created out of old drinking troughs gathered from fields on the estate. There is also a bamboo walk.

- The Emperor Fountain: In 1843 Tsar Nicholas I of Russia informed the Duke that he was likely to visit Chatsworth the following year. In anticipation of this Imperial visit, the Duke decided to construct the world's tallest fountain, and set Paxton to work to build it. An 8 acres (3.2 ha) lake was dug on the moors 350 ft (110 m) above the house to supply the natural water pressure. The work was finished in just six months, continuing at night by the light of flares, and the resulting water jet is on record as reaching a height of 296 ft (90 m). However, the Tsar died in 1855 and never saw the fountain. Due to a limited supply of water, the fountain usually runs on partial power, reaching half its full height.[35] The water power found a practical use generating Chatsworth's electricity from 1893 to 1936. The house was then connected to the mains, and a new turbine was installed in 1988 that produces about a third of the electricity the house needs.

- The Conservative Wall is a set of greenhouses that run up the slope from Flora's Temple to the stables against the north wall of the garden. A tall central section is flanked by ten smaller sections used to grow fruit and camellias. Two Camellia reticulata 'Captain Rawes' planted in 1850 survive. Chatsworth's camellias have won many prizes. The name of the building has no political connotations; the Dukes of Devonshire were Whigs and later Liberals.

- The bust of the 6th Duke on a Poseidon Temple column was erected in the 1840s and situated at the south end of today's Serpentine Hedge.[36] The four classical column drums beneath were a gift from the 6th Duke's half brother, Augustus Clifford, who collected these drums from the site of the Temple of Poseidon, Cape Sounion between 1821 and 1825, during his naval service as the captain of HMS Euryalus.[37] The column is possibly composed by the bottom, 3rd, 4th, and the 6th drum from a single collapsed temple column,[38] while the British Museum preserves the 7th.[39] The inscription on the pedestal erroneously credits the origin of these drums to the Temple of Athena, Cape Sounion, a smaller site located 380 m (1,250 ft) north-west of the Temple of Poseidon.

Two significant features from the period have been lost:

- The Great Conservatory, also known as the "Great Stove", was the largest glasshouse in the world at that time. Paxton and architect Decimus Burton designed this glasshouse, which was begun in 1836 and completed in 1841 at a cost of £33,099. It was 277 ft (84 m) long, 123 ft (37 m) wide and 61 ft (19 m) high. It used eight coal-fired furnaces to send hot water through 7 mi (11 km) of pipes.[40] A carriage drive ran the length of the building between lush tropical vegetation. One W. Adam called it "A mountain of glass... an unexampled structure... like a sea of glass when the waves are settling and smoothing down after a storm." The King of Saxony compared it to "a tropical scene with a glass sky". The Great Conservatory was demolished in 1920, as it had not been heated during World War I to conserve coal.

- The Victoria regia House or Lily House, built by Paxton in 1849–1850, was devoted to the giant Amazon water lily Victoria amazonica, which flowered in captivity there for the first time. Like the Great Conservatory, the Lily House was unused in World War I and demolished in 1920.

Modern garden (1950–present)[edit]

The 7th–10th Dukes made few changes to the garden, which suffered in the Second World War, but the 11th Duke and his wife were keen gardeners and oversaw a revival. Gardening personality Alan Titchmarsh wrote in 2003, "Chatsworth's greatest strength is that its owners have refused to let the garden rest on its Victorian laurels. It continues to grow and develop, and that is what makes it one of the best and most vibrant gardens in Britain." Many historical features have been immaculately restored, and unusually for a modern country-house garden, many new features have been added, including:

- The South Lawn limes: Double rows of pleached red-twigged limes on either side of the South Lawn, which were planted in 1952 and removed in 2014

- The Serpentine Hedge: A wavy-hedged beech corridor from the Ring Pond to the bust of the 6th Duke. It was planted in 1953.

- The Maze: planted with 1,209 yews in the centre of the site of the former Great Conservatory in 1962. Two flower gardens occupy the rest of the site.

- The Display Greenhouse (1970): Modern in style, but unobtrusively sited behind the First Duke's greenhouse. It has three climate zones: tropical, Mediterranean and temperate. Public access is limited but groups may book tours and there are first-come-first-served tours on a few days each season.

- The Cottage Garden: Inspired by an exhibit at the 1988 Chelsea Flower Show. A front garden of flower beds bordered by box leads to the "kitchen/dining" room with furniture covered with plants. There is a bedroom in the same style on the upper level.

- The Kitchen Garden: a productive fruit and vegetable garden with decorative features. It was created behind the stables in the early 1990s. Chatsworth's original kitchen garden covered 11.5 acres (5 ha) and was by the river in the park.

- Modern sculpture includes such pieces as War Horse and Walking Madonna by Dame Elisabeth Frink, and 14 bronze portrait heads by Angela Conner.

- The Sensory Garden is accessible to the disabled and features many fragrant plants. It was opened in 2004 by the then Home Secretary David Blunkett.

- Quebec: A 4-acre (16,000 m2) part of the garden to the south and west of the canal pond that was, until 2006, a neglected and dank area covered with Rhododendron ponticum. This is now an extension to the Arboretum walk, with a path along the top of the steep bank. The new walk gives views out into the south park, across the River Derwent and up the hill towards New Piece wood. An 18th-century cascade was uncovered during the clearance.[41]

Stables[edit]

The stable block at Chatsworth is prominent on the rising ground to the north-east of the house. Its entrance gate features four Doric columns with rustic banding, a pediment with a huge carving of the family coat of arms, two life-size stags embellished with real antlers, and a clock tower topped by a cupola. This was designed by James Paine for the 4th Duke and was built in 1758–1767. It is about 190 feet (60 m) square and two storeys tall. There are low towers in the corners and one over the entrance gate. The stables originally had stalls for 80 horses and all necessary equine facilities including a blacksmiths shop. The first floor was taken by granaries and accommodation for the many stable staff. According to the Dowager Duchess's Chatsworth: The House, one room still has "Third Postillion" painted on the door. The 6th Duke added a carriage house behind the stables in the 1830s.

The last horses left the stables in 1939, when the building became a store and garage. The grooms' accommodation was turned into flats for Chatsworth employees and pensioners. When the house reopened after the war, "catering" was limited to an outdoor tap, which has since been relabelled "water for dogs". In 1975 a tea bar was set up with an investment of £120. The first attempt at a café opened in 1979. It seated 90 in some old horse stalls in the stables and was unsatisfactory to customers and from a commercial point of view. In 1987 the Duke and Duchess's private chef, a Frenchman named Jean-Pierre Béraud who was also a leading light in the success of the Chatsworth Farm Shop and Chatsworth Foods, took charge. After a failed attempt to gain planning permission for a new building incorporating the old ice house in the park, a 250-seat restaurant was created in the carriage house. The 19th-century coach used by the Dowager Duchess and the late Duke at the Queen's Coronation is on display there. Other facilities include The Cavendish Rooms, which also serves refreshments, a shop, and three rooms for hire. The stables cater for 30,000 people a month in the visitor season.

Park, woods and farmyard[edit]

Chatsworth park of about 1,000 acres (4.0 km2) is open to free of charge all year round, except for the south-east section, the Old Park, which is used for breeding by herds of red and fallow deer. The stance of the Dukes on wider access rights has changed much. On the 11th Duke's death in 2004, the Ramblers Association praised him for enlightened championing of open access and his apologies for the attitude of the 10th Duke, who had restricted access to much estate land. Even under the 11th Duke, disputes arose: when the definitive rights of way were being compiled in the 1960s and 1970s, the footpath to the Swiss Cottage (an isolated house by a lake in the woods) was contested, and the matter went to the High Court, making Derbyshire one of the last counties to settle its definitive maps.

Farm stock also graze in the park, many belonging to tenant farmers or smallholders, who use it for summer grazing. Bess of Hardwick's park was wholly on the east side of the river and only extended as far south as the Emperor Fountain and as far north as the cricket ground. Seven fish ponds were dug to the north-west of the house, where the large flat area is used now for events such as the annual Chatsworth Horse Trials and the Country Fair, typically held near the end of August.[42] The bridge over the river was at the south end of the park and crossed to the old village of Edensor, which was by the river in full sight of the house.

Capability Brown did at least as much work in the park as he did in the garden. The open, tree-flecked landscape admired today is man-made. Brown straightened the river and put a network of drainage channels under the grass. The park is fertilised with manure from the estates farms; weeds and scrub are kept under control. Brown filled in most of the fishponds and extended the park to the west of the river. Meanwhile James Paine designed a new bridge to the north of the house, set at an angle of 40 degrees to command the best view of the West Front of the house. Most of the houses in Edensor were demolished and the village was rebuilt out of sight of the house. The hedges between the fields on the west bank of the river were grubbed up to create open parkland and woods were planted on the horizon. These were arranged in triangular clumps, so that a screen of trees could be maintained when each planting had to be felled. Brown's plantings reached their peak in the mid-20th century and are gradually being replaced. The 5th Duke had an elegant red-brick inn built at Edensor to cater to a growing number of well-to-do travellers coming to see Chatsworth. It is now the estate office.

In 1823 the Bachelor Duke acquired the Duke of Rutland's land around Baslow to the north of Chatsworth in exchange for land elsewhere. He extended the park about half a mile (800 m) north to its present limits. He had the remaining cottages of Edensor inside the park demolished, apart from the home of one old man who did not wish to move, which still stands in isolation today. The houses in Edensor were rebuilt in picturesque pattern-book styles. In the 1860s the 7th Duke had St Peter's Church, Edensor, enlarged by Sir George Gilbert Scott. The church spire embellishes the views from the house, garden and park. Inside there is a remarkable monument to Bess of Hardwick's sons Henry Cavendish and William, 1st Earl of Devonshire. St Peter's in Edensor is where the 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th and 11th Dukes and their wives are buried, not in a vault inside the church, but in individual graves marked by simple headstones, in the Cavendish family plot overlooking the churchyard.

On the hills of the eastern side of the park is Stand Wood. The Hunting Tower there was built in 1582 by Bess of Hardwick. At the top is a plateau of several square miles of lakes, woods and moorland. There are public paths through the area and Chatsworth offers guided tours with commentary in a 28-seater trailer pulled by a tractor. The area is the water source for the gravity-fed waterworks in the garden. The Swiss Lake feeds the Cascade and the Emperor Lake the Emperor Fountain. The Bachelor Duke had an aqueduct built, over which water tumbles on its way to the cascade.

The late Deborah, Dowager Duchess of Devonshire, was a keen advocate of rural life. In 1973 a Chatsworth Farmyard exhibit was opened in the old building yard above the stables at explaining how food was produced. There are milking demonstrations and displays of rare breeds. An adventure playground was added in 1983. A venue for talks and exhibitions called Oak Barn was opened by the television gardener Alan Titchmarsh in 2005. Chatsworth also runs two annual rural-skills weeks, in which demonstrations of agricultural and forestry are given to groups of schoolchildren on the estate farms and woods.

In 2001, the ashes of Air Vice Marshal James Edgar Johnson CB, CBE, DSO & Two Bars, DFC & Bar, DL, a Second World War flying ace, were scattered on the Chatsworth estate. There is a bench dedicated to his memory at his favourite fishing spot on the estate; the inscription reads "In Memory of a Fisherman".[43]

Estate[edit]

Chatsworth is the hub of a 35,000-acre (140 km2) agricultural estate. This, together with 30,000 acres (120 km2) around Bolton Abbey in Yorkshire (mostly moorland) and some land in Eastbourne and Carlisle belongs to The Trustees of Chatsworth Settlement, a family trust established in 1946. The Duke and other members of the family are entitled to the income. The family's 8,000-acre (32 km2) Lismore Castle estate in Ireland is held in a separate trust. The estate includes dozens of tenanted farms and over 450 houses and flats. There are five sub-estates scattered across Derbyshire:

- The Main Estate is a compact block of 12,310 acres (4,982 ha) around the house, including the park and many properties in the villages of Baslow, Pilsley, Edensor, Beeley, and Calton Lees.

- The West Estate is 6,498 acres (26.30 km2) of scattered high ground, mostly in the Peak District and partly in Staffordshire. Hartington, from which the family takes its secondary title is nearby.

- The Shottle Estate is 3,519 acres (14.24 km2) in and around Shottle, which is around 15 miles (24 km) south of Chatsworth. This low-lying land is home to most of the dairy farms on the estate and also has some arable farms.

- The Staveley Estate 3,400 acres (14 km2) at Staveley near Chesterfield includes a 355 acres (1.44 km2) industrial site called Staveley Work, let to various tenants, and some woodlands and arable farms.

- The Scarcliffe Estate, mostly arable farms, is 9,320 acres (37.7 km2) east of Chesterfield.

The Chatsworth Settlement has a range of sources of income in addition to agricultural rents. Several thousand acres, mostly round Chatsworth and on the Staveley estate, are farmed in hand. Several properties can be rented as holiday cottages, including Bess of Hardwick's Hunting Tower in the park. Several quarries produce limestone and other minerals.

The 11th Duke and Duchess did not opt for a "theme park" approach to modernising a country estate. They eschewed the traditional aristocratic reluctance to participate in commerce. The Chatsworth Farm Shop is a large enterprise employing over a hundred.[44][failed verification] A 90-seat restaurant opened at the Farm Shop in 2005. From 1999 to 2003 there was also a shop in the exclusive London district of Belgravia, but it was unsuccessful and closed down.

The Settlement runs the four shops and the catering operations at Chatsworth, paying a percentage of turnover to the charitable Chatsworth House Trust in lieu of rent. It also runs the Devonshire Arms Hotel and the Devonshire Fell Hotel & Bistro on the Bolton Abbey estate and owns the Cavendish Hotel at Baslow, on the edge of Chatsworth Park, which is let to a tenant. The old kitchen garden at Barbrook on the edge of the park is let to the Caravan Club; a paddock at the south end of the park where bucks were fattened for Chatsworth's table is a tenanted garden centre. In both cases the Settlement receives a percentage of turnover as rent.

There is a line of Chatsworth branded foods endorsed with the Dowager Duchess's signature and available by mail order. She also established Chatsworth Design to exploit intellectual property rights to the Devonshire collections, and a furniture company called Chatsworth Carpenters, but the latter has now been licensed to an American company.

In popular culture[edit]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2023) |

Chatsworth House has been referenced in literature and used as a location set for films, television and for music videos including: Pride and Prejudice (1813); Maiden Voyage (1943); Barry Lyndon (1975); The Bounty (1984); Interceptor (1989); Pride and Prejudice (1995); Pride & Prejudice (2005);[45] Face to Face; The Duchess (2008); The Wolfman (2009); Rivers with Griff Rhys Jones (2009); Chatsworth (2012); Death Comes to Pemberley (2013); Austenland (2013); Secrets of The Manor House (2014); "Breathless Beauty, Broken Beauty" (2014); The Crown (2016) and Peaky Blinders.[46]

Gallery[edit]

-

The State Music Room completed 1694

-

The Great Chamber completed 1694

-

Sculpture Gallery completed c. 1834 designed by Jeffry Wyatville

-

Great Dining Room completed 1832 designed by Jeffry Wyatville

-

Dome above the Oak Staircase 1823-29 by Jeffry Wyatville

-

The altarpiece in the chapel, completed 1693 designed by Caius Gabriel Cibber carved by Samuel Watson (sculptor). The bronze work, 2.5m tall, is by the artist Damien Hirst. Named 'Saint Bartholomew, Exquisite Pain' it was completed in 2006 for the annual Sotheby's modern sculpture exhibition held at Chatsworth.

-

The ceiling of the Great Staircase painted by Antonio Verrio 1691 depicting The Triumph of Cybele

See also[edit]

- Grade I listed buildings in Derbyshire

- Listed buildings in Chatsworth, Derbyshire

- Historic houses in England

- List of historic houses

- Treasure Houses of Britain

Other properties owned by the Dukes of Devonshire, currently or in the past, include:

- Bolton Abbey

- Burlington House

- Chiswick House

- Compton Place

- Devonshire House

- Hardwick Hall

- Holker Hall

- Lismore Castle

- Londesborough Hall

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c Historic England. "Chatsworth House (Grade I) (1373871)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Chatsworth Receives Top Honour in Prestigious NPI National Heritage Awards". Prnewswire.co.uk. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Award boosts stately home visitors". BBC News. 25 August 2003. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Chatsworth House open after restoration". BBC News. 13 March 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ "The Chatsworth House Trust". Peak District Online. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ a b Hall, Rev. George (1839). The history of Chesterfield: with particulars of the hamlets contiguous to the town and descriptive accounts of Chatsworth Hardwick and Bolsover. London: Whittaker and Co.

- ^ Thompson, Francis (1949). "1". A history of Chatsworth: being a supplement to the sixth Duke of Devonshire's handbook. Country Life. p. 21.

- ^ Digby, George Wingfield (1964). Elizabethan Embroidery. Thomas Yoseloff. pp. 58–63. ASIN B0042KP67G.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ "Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679)". BBC. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Malcolm, Noel (2003). Aspects of Hobbes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 80. ISBN 0199247145.

- ^ Hastings, Chris (9 August 2008). "Princess Diana and the Duchess of Devonshire: Striking similarities". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Your Guide to Chatsworth. Streamline Press Ltd. 2012. ISBN 978-0-9537329-1-3.

- ^ History, Gazetteer, and Directory of Derbyshire With the Town of Burton Upon Trent (1846). Kessinger Publishing. 10 September 2010. p. 492. ISBN 978-1164674504.

- ^ "Handbook of Chatsworth and Hardwick". Chatsworth. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "The Devonshire Family Collections at Chatsworth". Archives Hub. 4 March 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Chaves, José Joubert, ed. (5 December 1904). "Viagem Real — Os Reis de Portugal Sob a Nevada em Chatsworth" [Royal Trip — The King and Queen of Portugal under the Snow in Chatsworth]. Illustração Portugueza (in Portuguese). Lisbon. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ West London Observer, March 1929.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Peak District Online Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ "Cinema Museum Home Movie Database.xlsx". Google Docs. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ "Deborah Mitford". Goodreads. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Chatsworth House £32m restoration unveiled". BBC News. 24 March 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ "Edensor and the Chatsworth Estate". Chatsworth Estate. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "The Devonshire Family Collections at Chatsworth". Archives Hub. 4 March 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "An English Manor Travels Across the Pond and Opens for Visitors". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Treasures from Chatsworth: The Exhibition". Sotheby's. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ "History revealed". www.chatsworth.org. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ "Extreme Heat Uncovers Lost Villages, Ancient Ruins and Shipwrecks". Bloomberg.com. 12 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Tomlinson, Lucy (11 October 2012). "Inside Chatsworth House". Britain Magazine.

- ^ Anon. "Chatsworth House". tour K. Just Tour Ltd. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ "Chatsworth – photo library". 28 September 2007. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ Dorment, Richard (17 March 2010). "Chatsworth House: a masterpiece in every room". The Telegraph.

- ^ "Chatsworth's Cascade is the best in England". 28 September 2007. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ Emperor Fountain goes sky high, Chatsworth press release, 25 April 2007.

- ^ Historic England (19 June 1987). "DORIC COLUMN AND THE BUST OF SIXTH DUKE (Grade II) (1051668)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Liddel, Peter; Low, Polly (2019). "Chatsworth". Attic Inscriptions in UK Collections. 7.

- ^ Breschi, Luigi (1970). "Disiecta membra del tempio di Poseidon a Capo Sunio". Annuario della Scuola Archeologica di Atene. 47–48: 417–433.

- ^ "column | British Museum". The British Museum. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Schama, Simon (1996). Landscape and Memory. Vintage. p. 565. ISBN 0679735127.

- ^ "Hidden Gems Walking Tour" (PDF). Chatsworth Estate. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Chatsworth Country Fair". Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ Sarkar, Dilip (2011). Spitfire! Courage and Sacrifice. London: Ramrod Publications. pp. 303–304. ISBN 978-0-9550431-6-1.

- ^ "About the farm shop". Chatsworth. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ "Carol M. Dole". jasna.org. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ Harrisson, Juliette (24 September 2014). "Helen McCrory interview: Peaky Blinders series 2". Den of Geek. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

I think we had three days away in Chatsworth House for one character's home, a new character that's coming in, but apart from that...

References and further reading[edit]

- Chatsworth: A Short History (1951) by Francis Thomson (librarian and keeper of collections at Chatsworth). Country Life Limited.

- Chatsworth: The House (2002 ed.) by the Duchess of Devonshire. Frances Lincoln Limited. ISBN 0-7112-1675-4

- Chatsworth, Arcadia, Now: Seven Scenes from the Life of a House (2021) by John-Paul Stonard. Particular Books. ISBN 024146191X

- English Country Houses: Baroque (1970) by James Lees-Milne. Country Life / Newnes Books. ISBN 1-85149-043-4

- The Estate: A View from Chatsworth (1990) by the Duchess of Devonshire. MacMillan. ISBN 0-333-47170-9

- Boschung, Dietrich; von Hesberg, Henner; Linfert, Andreas (1997). Die antiken Skulpturen in Chatsworth sowie in Dunham Massey und Withington Hall. Corpus Signorum Imperii Romani Great Britain. Vol. 3, 8. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 3-8053-1991-6.

- The Garden at Chatsworth (1999) by the Duchess of Devonshire. Frances Lincoln Limited. ISBN 0-7112-1430-1

- Chatsworth Cookery Book (2003) by the Duchess of Devonshire. Frances Lincoln Limited. ISBN 0-7112-2257-6

- Raffaele De Giorgi, "Couleur, couleur!". Antonio Verrio: un pittore in Europa tra Seicento e Settecento (Edifir, Firenze 2009). ISBN 9788879704496

External links[edit]

- Chatsworth House: Official website

- Chatsworth House Trust page from the Charity Commission – includes links to annual reports

- Photographs of Chatsworth House taken by John Gay

- Country houses in Derbyshire

- Gardens in Derbyshire

- English gardens in English Landscape Garden style

- Grade I listed buildings in Derbyshire

- Grade I listed houses

- Grade I listed bridges

- Grade I listed stables

- Grade I listed garden and park buildings

- Cavendish family

- Houses completed in 1696

- English Baroque architecture

- English Baroque gardens

- Fountains in the United Kingdom

- Historic house museums in Derbyshire

- Tourist attractions of the Peak District

- Mazes

- Gardens by Capability Brown

- Thomas Archer buildings

- 1696 establishments in England

- William Talman buildings

- Country estates in England