Eric Morecambe

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

Eric Morecambe | |

|---|---|

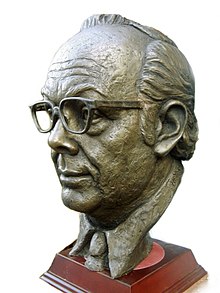

Bronze bust by Victor Heyfron, 1963 | |

| Born | John Eric Bartholomew 14 May 1926 Morecambe, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 28 May 1984 (aged 58) Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1941–1984 |

| Spouse |

Joan Bartlett (m. 1952) |

| Children | 3 (1 adopted) |

| Family | Jack Bartholomew (uncle) |

John Eric Bartholomew OBE (14 May 1926 – 28 May 1984), known by his stage name Eric Morecambe, was an English comedian who together with Ernie Wise formed the double act Morecambe and Wise. The partnership lasted from 1941 until Morecambe's death in 1984. Morecambe took his stage name from his home town, the seaside resort of Morecambe in Lancashire.

He was the co-star of the BBC1's television series The Morecambe & Wise Show, which for the 1977 Christmas episode gained UK viewing figures of over 28 million people. One of the most prominent comedians in British popular culture, in 2002 he was named one of the 100 Greatest Britons in a BBC poll.[1]

Early life and childhood career[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

Eric Morecambe was born at 12.30pm on Friday 14 May 1926 at 42 Buxton Street, Morecambe, Lancashire[2][3] to George and Sarah Elizabeth "Sadie" (née Robinson) Bartholomew. He was christened on 6 June as John Eric Bartholomew.[4] Sadie took work as a waitress to raise funds for his dancing lessons. During this period, Eric Bartholomew won numerous talent contests, including one in Hoylake in 1940 for which the prize was an audition in Manchester for Jack Hylton. Three months after the audition, Hylton invited Morecambe to join a revue called Youth Takes a Bow[5] at the Nottingham Empire, where he met Ernest Wiseman, who had been appearing in the show for some years as "Ernest Wise".[6] The two soon became very close friends, and with Sadie's encouragement started to develop a double act.

When the two were eventually allowed to perform their double act on stage (in addition to their solo spots), Hylton was impressed enough to make it a regular feature in the revue. However, the duo were separated when they came of age for their War Service during the final stages of the Second World War. Wise joined the Merchant Navy, while Morecambe was conscripted to become a Bevin Boy and worked as a coal miner in Accrington from May 1944 onwards.

Career[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

Morecambe and Wise[edit]

After the war, Morecambe and Wise began performing on stage and radio and secured a contract with the BBC to make a television show, where they started the short-lived show Running Wild in 1954, which was poorly received. They returned to the stage to hone their act, and later made appearances on Sunday Night at the London Palladium and Double Six.[7]

Two of a Kind: 1961–1968[edit]

In 1961, Lew Grade offered the duo a series for the London-based ITV station ATV. Entitled Two of a Kind, it was written by Dick Hills and Sid Green. An Equity strike halted that show, but Morecambe and Wise were members of the Variety Artists' Federation, then a separate trade union unaffiliated with Equity. Green and Hills later appeared in the series as "Sid" and "Dick".

The sixth Morecambe and Wise series for ATV was planned from the start to be aired in the United Kingdom as well as exported to the United States and Canada. It was taped in colour and starred international guests, often American. Prior to its British run, it was broadcast in North America by the ABC network as a summer replacement for re-runs of The Hollywood Palace, under the title The Piccadilly Palace, from 20 May to 9 September 1967. All but two episodes of this series are now believed to be lost, with the surviving two episodes existing only as black-and-white copies, bearing the UK titles.

The duo had appeared in the US on The Ed Sullivan Show. In 1968, Morecambe and Wise left ATV to return to the BBC.

With the BBC: 1968–1978[edit]

While Morecambe was recuperating from a heart attack, Hills and Green, who believed that Morecambe would probably never work again, quit as writers. Morecambe and Wise were in Barbados at the time and learned of their writers' departure only from the steward on the plane. John Ammonds, the show's producer, replaced Hills and Green with Eddie Braben. Theatre critic Kenneth Tynan stated, Braben made Wise's character a comic who was not funny, while Morecambe became a straight man who was funny. Braben made them less hostile to one another.

Morecambe and Wise did annual BBC Christmas shows from 1968 to 1977, with the 1977 show having an estimated audience of 28,385,000, although at a time when there were only three UK television channels.[8] They were one of the most prominent comedy duos in British popular culture and in 1976 were both appointed OBEs. (Morecambe's wife, Joan, received an OBE in 2015 for her work with children's charities.)[9]

With Thames Television: 1978–1983[edit]

The pair left the BBC for ITV in January 1978, signing a contract with the London station Thames Television.

Morecambe suffered a second heart attack at his home in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, on 15 March 1979; this led to a heart bypass operation, performed by Magdi Yacoub on 25 June 1979. At that time, Morecambe was told he only had three months to live.[10]

Morecambe increasingly wanted to move away from the double act, and into writing and playing other roles. In 1980, he played the "Funny Uncle" in a dramatisation of the John Betjeman poem "Indoor Games Near Newbury", part of an ITV special titled Betjeman's Britain. Produced and directed by Charles Wallace, it spawned the start of a working relationship that led to a follow-up in 1981 for Paramount Pictures titled Late Flowering Love in which Morecambe played an RAF major.[citation needed] The film was released in the UK with Raiders of the Lost Ark. In 1981, Morecambe published Mr Lonely, a tragicomic novel about a stand-up comedian. He began to focus more on writing.

They also appeared together recalling their music hall days in a one-hour special on ITV on 2 March 1983, called Eric & Ernie's Variety Days. During this time Morecambe published two other novels: The Reluctant Vampire (1982) and its sequel, The Vampire's Revenge (1983). Morecambe and Wise's final show together was the 1983 Christmas special for ITV.

Morecambe and Wise worked on a television movie in 1983, Night Train to Murder, which was broadcast on ITV in January 1985. Continuing his collaboration with Wallace, Morecambe also acted in a short comedy film called The Passionate Pilgrim opposite Tom Baker and Madeline Smith, again directed by Wallace for MGM/UA. It was released in the cinema with the James Bond film Octopussy and later with WarGames. Wallace and Morecambe were halfway through filming a fourth film when Morecambe died. It was never completed.

Personal life[edit]

Eric Morecambe married Joan Bartlett in Margate Thanet, Kent on Thursday, 11 December 1952. They held their wedding reception at the Bulls Head pub in Margate.They had three children: Gail (born 1953); Gary (born 1956) and Steven (who was born in 1970, and whom they adopted in 1974). Joan Bartlett Morecambe died on her 97th birthday on 26 March 2024.

In his leisure time, Eric was a keen birdwatcher, and the statue of him at Morecambe shows him wearing his binoculars. The RSPB named a hide after him at the nearby Leighton Moss nature reserve in recognition of his support. In 1984 the RSPB bought the 459 hectares (1,130 acres) Old Hall Marshes Reserve near Tolleshunt D'Arcy in Essex for £780,000 helped by donations to the Eric Morecambe Memorial Appeal.[11]

Morecambe was the nephew of the rugby league footballer John "Jack" Bartholomew.[12]

Morecambe sent a message of support (along with various celebrities) to Margaret Thatcher after she won the 1979 general election, wishing her luck during the 1979 European election campaign.[13] His message ended, "God bless you, Maggie, and good luck in the European Campaign and it is your round next."[14]

Health problems[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

In a diary entry from 17 August 1967, when Morecambe and Wise were appearing in Great Yarmouth as part of a summer season, Morecambe observed: "I have a slight pain on the left side around my heart. It's most likely wind, but I've had it for about four days. That's a hell of a time to have wind."[15]

Morecambe was a hypochondriac, but he rarely wrote about his health concerns until after his first heart attack. At the time, Morecambe was smoking 60 cigarettes a day and drinking heavily. He suffered a near-fatal heart attack late on 7 November 1968 after a show, while driving back to his hotel outside Leeds.

Morecambe had been appearing with Wise during a week of midnight performances at the Variety Club in Batley, Yorkshire. Morecambe and Wise appeared there in December 1967 for a week, making £4,000 (equivalent to £77,000 in 2021[16]).

Since the beginning of the week Morecambe noticed he had pains in his right arm but thought little of it, thinking the pains were tennis elbow or rheumatism. That night, he headed back to his hotel, and recounted in an interview with Michael Parkinson in November 1972 that, as the pains spread to his chest, he became unable to drive. He was rescued by a passerby as he stopped the car. The first hospital they arrived at had no Accident and Emergency. At the second one, Morecambe admitted himself and a heart attack was immediately diagnosed. Morecambe was due to appear at the London Palladium with his partner Ernie Wise on 18 November 1968 but had to miss the performance as he was recovering in hospital. The comedian Frankie Howerd and impressionist Mike Yarwood were both late stand-ins for them instead.

After leaving hospital on 24 November 1968 under orders not to work for three months[17] Morecambe gave up his cigarette habit and started smoking a pipe, as he mentioned that he was trying to do in August 1967. He also stopped doing summer and winter seasons and reduced many of his public engagements. Morecambe took six months off, returning for a press call at the BBC Television Centre in May 1969. On 27 July of that year, Morecambe and Wise returned to the stage at the Bournemouth Winter Gardens, and received a four-minute standing ovation.

Morecambe suffered a second heart attack in March 1979[18] and underwent bypass surgery in June.[19]

Death[edit]

Morecambe took part in a charity show, hosted by close friend and comedian Stan Stennett, at the Roses Theatre in Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire, on Sunday 27 May 1984. His wife Joan, who was in the audience, recalled that Morecambe was "on top form".[20]

After the show had ended and Morecambe had first left the stage, the musicians returned and picked up their instruments. He rushed back onto the stage to join them and played various instruments making six curtain calls. On leaving the stage for the final time as the house tabs fell, he stepped into the wings and collapsed with his third heart attack in 16 years. He was rushed to Cheltenham General Hospital, where he died just before 3 a.m on Monday 28 May.[21]

His funeral was held on 4 June at St Nicholas Church, Harpenden with the principal address delivered by Dickie Henderson. There was a private cremation service at Garston. His ashes were later returned to the church for burial in the Garden of Remembrance.[citation needed]

Ernie Wise said in an interview, "I think I had two sad days, I think – when my father died and, actually, when Eric died."[22]

Legacy[edit]

- A larger-than-life statue of Morecambe, created by sculptor Graham Ibbeson, was unveiled by the Queen at Morecambe in July 1999 and is surrounded by inscriptions of many of his favourite catchphrases and an exhaustive list of guest stars who appeared on the show. The statue was vandalised in October 2014, having had one of its legs sawn off, it was moved to London for repair and was restored on 11 December 2014.[23]

- In Harpenden, Hertfordshire, where Morecambe and his family lived from the 1960s until his death, the public concert hall is named after him, with a portrait of Morecambe hanging in the foyer. Morecambe often referred to Harpenden in his comedy, with a band once appearing on the show named The Harpenden Hot-Shots and in a Casanova sketch he introduced himself as Lord Eric, Fourth Duke of Harpenden "and certain parts of Birkenhead". Morecambe was the guest of honour, and performed the opening ceremony at the 75th Anniversary Fete of St George's School, Harpenden.

- A West End Show, The Play What I Wrote, opened in 2001 as a tribute to the duo. Directed by Kenneth Branagh, each performance featured a different guest celebrity.[24] In March 2003, the show transferred to Broadway.[25]

- In 2003, Morecambe's eldest son Gary released "Life's Not Hollywood, It's Cricklewood", a biography of his father from the point of view of his family, using family photos and extracts from previously unseen diaries.

- Kenilworth Road Stadium, the home of Luton Town F.C., has a suite named after Morecambe. He was a supporter and one-time president of the club.[citation needed]

- J D Wetherspoon opened a public house called The Eric Bartholomew in Morecambe in 2004.[26]

- At the Roses Theatre in Tewkesbury, the Eric Morecambe Room is used by local and national companies for conferences and meetings.

- There is a bird hide named after him at Leighton Moss RSPB reserve, which is on Morecambe Bay, near Carnforth, Lancashire.[27]

- The play Morecambe was created as a celebration of the life of Eric Morecambe. It played at the Edinburgh fringe festival in 2009 and subsequently transferred to London's West End before embarking on a UK tour in 2010.[citation needed]

- In February 2016 Morecambe's 1968 Jensen Interceptor, which he had bought for £4,500, was offered for sale at £150,000.[28]

Bibliography[edit]

- Mister Lonely (novel) by Eric Morecambe (1981) ISBN 0-413-48170-0

- Stella (novel) by Eric Morecambe (completed by Gary Morecambe) (2012) ISBN 9780007395071

References[edit]

- ^ "100 great British heroes". BBC News. Retrieved 15 February 2014

- ^ Marcus, Laurence. "The Legendary Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise Part One of Two".

- ^ "Eric statue brings lasting sunshine". 9 July 2009.

- ^ Eric Morecambe Unseen: The Lost Diaries, Jokes and Photographs – William Cook

- ^ Sellers, Robert. (2011). Little Ern! : the authorized biography of Ernie Wise. Hogg, James, 1971–. London: Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-283-07150-8. OCLC 730403484.

- ^ Theatre Programme: 10 July 1939, London Palladium, Band Waggon, a revue which incorporated a segment "Youth Takes a Bow" featuring "Ernest Wise".

- ^ Double Six at IMDb

- ^ "Eric Morecambe: Growing up with a comic legend", The Guardian, 17 October 2009

- ^ "Royal nod for Eric Morecambe's widow". thevisitor.co.uk.

- ^ TVAM interview with Morecambe, 18 April 1984

- ^ RSPB Birds magazine, Old Essex Coast:Old Hall Marshes, p. 50 (Spring 2005)

- ^ Tom Mather (2010). "Best in the Northern Union", pp. 128–142. ISBN 978-1-903659-51-9

- ^ "Transition to power | Margaret Thatcher Foundation". Margaretthatcher.org. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Letter of support" (PDF). Margaretthatcher.org. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ Eric Morecambe Unseen: The Lost Diaries, Jokes and Photographs – William Cook – 2005.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Print of Eric Morecambe leaves hospital for home, November 1968. Comedian Eric Morecambe".

- ^ "ERIC MORECAMBE AND ERNIE WISE – PART 2 – A TELEVISION HEAVEN BIOGRAPHY". Televisionheaven.co.uk. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ "This Is Their Life". Morecambeandwise.com. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ Joan Morecambe, Morecambe and Wife, p. 180 (1985)

- ^ McGann, Graham Morecambe & Wise, (1999), p. 300

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Ernie Wise talks about the death of Eric Morecambe – 1984". YouTube. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "Eric Morecambe statue returns after attempted theft". BBC News. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Sara Gaines (6 November 2001). "The play wot they wrote". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Charles Isherwood (30 March 2003). "'The Play What I Wrote'". Variety (review). Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Nick Lakin (19 March 2021). "The Lancaster district pubs featured in the 2021 Good Beer guide as CAMRA celebrates 50 years". Lancaster Guardian. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ "Eric Morecambe's daughter brings sunshine". Westmorland Gazette. 30 October 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "Eric Morecambe's Jensen Interceptor for sale at £150,000". BBC News. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

Further reading[edit]

- Morecambe and Wife – Joan Morecambe and Michael Leitch (1985) ISBN 0-7207-1616-0

- Morecambe and Wise : Behind the Sunshine – Gary Morecambe, Martin Sterling (1995) ISBN 0330341405

- Morecambe & Wise – Graham McCann (1998) ISBN 1-85702-735-3

- Memories of Eric – Gary Morecambe and Martin Sterling (1999) ISBN 978-0-233996691

- Eric Morecambe : Life's not Hollywood, it's Cricklewood – Gary Morecambe (2003) ISBN 0-563-52186-4

- Eric Morecambe Unseen : The Lost Diaries Jokes and Photographs – William Cook (ed.) (2005) ISBN 0-00-723465-1

- You'll Miss Me When I'm Gone : The life and work of Eric Morecambe – Gary Morecambe (2009) ISBN 978-0-00-728732-1

- Eric Morecambe Lost and Found – Gary Morecambe (ed.)(2012) ISBN 9781849543361

- Who Killed Eric Morecambe? (the decline & fall of British television) – Charles Wallace (Nov 2012) ASIN B00A4COP64

- Driving Mr Morecambe : A Chauffeur's Story – Michael Fountain, Paul Jenkinson (2013) ISBN 9780755207329

- Morecambe and Wise: Bring Me Sunshine – Gary Morecambe (2013) ISBN 9781780973982

External links[edit]

- The Morecambe & Wise homepage Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Morecambeandwise.com News Reviews And Information

- Eric Morecambe website run by daughter Gail Morecambe

- Find a Grave Eric Morcambe

- Eric Morecambe at IMDb

- Eric Morecambe at British Comedy Guide

- Portraits of Eric Morecambe at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- 1926 births

- 1984 deaths

- 20th-century English comedians

- 20th-century English male actors

- Actors from Morecambe

- BAFTA fellows

- Best Entertainment Performance BAFTA Award (television) winners

- Bevin Boys

- Birdwatchers

- Burials in Hertfordshire

- Comedians from Lancashire

- English male comedians

- English sketch comedians

- English male television actors

- English miners

- Hypochondriacs

- Luton Town F.C.

- Male actors from Lancashire

- Morecambe and Wise

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- Television personalities from Lancashire