Freddie Mac

Former logo used until 2016 | |

| Company type | Government-sponsored enterprise and public company |

|---|---|

| OTCQB: FMCC | |

| Industry | Financial services |

| Founded | 1970 |

| Headquarters | Tysons, Virginia, U.S. (McLean mailing address) |

Key people |

|

| Products | Mortgage-backed securities |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 7,799 (January 31, 2023) |

| Website | www |

| Footnotes / references [1][2] | |

The Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC), commonly known as Freddie Mac, is a publicly traded, government-sponsored enterprise (GSE), headquartered in Tysons, Virginia.[3][4] The FHLMC was created in 1970 to expand the secondary market for mortgages in the US. Along with its sister organization, the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), Freddie Mac buys mortgages, pools them, and sells them as a mortgage-backed security (MBS) to private investors on the open market. This secondary mortgage market increases the supply of money available for mortgage lending and increases the money available for new home purchases. The name "Freddie Mac" is a variant of the FHLMC initialism of the company's full name that was adopted officially for ease of identification.

On September 7, 2008, Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) director James B. Lockhart III announced he had put Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac under the conservatorship of the FHFA (see Federal takeover of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac). The action has been described as "one of the most sweeping government interventions in private financial markets in decades".[5][6][7] As of the start of the conservatorship, the United States Department of the Treasury had contracted to acquire US$1 billion in Freddie Mac senior preferred stock, paying at a rate of 10% per year, and the total investment may subsequently rise to as much as US$100 billion.[8] Shares of Freddie Mac stock, however, plummeted to about one U.S. dollar on September 8, 2008, and dropped a further 50% on June 16, 2010, when the stocks delisted due to falling below minimum share prices for the NYSE.[9] In 2008, the yield on U.S Treasury securities rose in anticipation of increased U.S. federal debt.[10] The housing market and economy eventually recovered, making Freddie Mac profitable once again.

Freddie Mac is ranked No. 45 on the 2023 Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by total revenue, and has $3.208 trillion in assets under management.[11]

History[edit]

From 1938 to 1968, the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) was the sole institution that bought mortgages from depository institutions, principally savings and loan associations, which encouraged more mortgage lending and effectively insured the value of mortgages by the US government.[12] In 1968, Fannie Mae split into a private corporation and a publicly financed institution. The private corporation was still called Fannie Mae and its charter continued to support the purchase of mortgages from savings and loan associations and other depository institutions, but without an explicit insurance policy that guaranteed the value of the mortgages. The publicly financed institution was named the Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae) and it explicitly guaranteed the repayments of securities backed by mortgages made to government employees or veterans (the mortgages themselves were also guaranteed by other government organizations).[13][14]

To provide competition for the newly private Fannie Mae and to further increase the availability of funds to finance mortgages and home ownership, Congress then established the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) as a private corporation through the Emergency Home Finance Act of 1970.[15] The charter of Freddie Mac was essentially the same as Fannie Mae's newly private charter: to expand the secondary market for mortgages and mortgage-backed securities by buying mortgages made by savings and loan associations and other depository institutions. Initially, Freddie Mac was owned by the twelve Federal Home Loan Banks and governed by the Federal Home Loan Bank Board.[16]

In 1989, the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989 ("FIRREA") revised and standardized the regulation of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. It also severed Freddie Mac's ties to the Federal Home Loan Bank System. The Federal Home Loan Bank Board (FHLBB) was abolished and replaced by different and separate entities. An 18-member board of directors for Freddie Mac was formed, and subjected to oversight by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Separately, The Federal Housing Finance Board (FHFB) was created as an independent agency to take the place of the FHLBB, to oversee the 12 Federal Home Loan Banks (also called district banks).

In 1995, Freddie Mac began receiving affordable housing credit for buying subprime securities, and by 2004, HUD suggested the company was lagging behind and should "do more".[17]

Freddie Mac was put under a conservatorship of the U.S. federal government on Sunday, September 7, 2008.[18]

Business[edit]

Freddie Mac's primary method of making money is by charging a guarantee fee on loans that it has purchased and securitized into mortgage-backed security (MBS) bonds. Investors, or purchasers of Freddie Mac MBS, are willing to let Freddie Mac keep this fee in exchange for assuming the credit risk. That is, Freddie Mac guarantees that the principal and interest on the underlying loan will be paid back regardless of whether the borrower actually repays. Owing to Freddie Mac's financial guarantee, these MBS are particularly attractive to investors and, like other Agency MBS, are eligible to be traded in the "to-be-announced", or "TBA" market.[19]

Conforming loans[edit]

The GSEs are allowed to buy only conforming loans, which limits secondary market demand for non-conforming loans. The relationship between supply and demand typically renders the non-conforming loan harder to sell (fewer competing buyers); thus it would cost the consumer more (typically 1/4 to 1/2 of a percentage point, and sometimes more, depending on credit market conditions). OFHEO, now merged into the new FHFA, annually sets the limit of the size of a conforming loan in response to the October to October change in mean home price. Above the conforming loan limit, a mortgage is considered a jumbo loan. The conforming loan limit is 50 percent higher in such high-cost areas as Alaska, Hawaii, Guam and the US Virgin Islands,[20] and is also higher for 2–4 unit properties on a graduating scale. Modifications to these limits were made temporarily to respond to the housing crisis, see jumbo loan for recent events.

Guarantees and subsidies[edit]

No actual government guarantees[edit]

The FHLMC states, "securities, including any interest, are not guaranteed by, and are not debts or obligations of, the United States or any agency or instrumentality of the United States other than Freddie Mac."[21] The FHLMC and FHLMC securities are not funded or protected by the US Government. FHLMC securities carry no government guarantee of being repaid. This is explicitly stated in the law that authorizes GSEs, on the securities themselves, and in public communications issued by the FHLMC.

Assumed guarantees[edit]

There is a widespread belief that FHLMC securities are backed by some sort of implied federal guarantee and a majority of investors believe that the government would prevent a disastrous default. Vernon L. Smith, 2002 Nobel Laureate in economics, has called FHLMC and FNMA "implicitly taxpayer-backed agencies".[22] The Economist has referred to "the implicit government guarantee"[23] of FHLMC and FNMA.

The then director of the Congressional Budget Office, Dan L. Crippen, testified before Congress in 2001, that the "debt and mortgage-backed securities of GSEs are more valuable to investors than similar private securities because of the perception of a government guarantee."[24]

Federal subsidies[edit]

This section needs to be updated. (September 2021) |

The FHLMC receives no direct federal government aid. However, the corporation and the securities it issues are thought to benefit from government subsidies. The Congressional Budget Office writes, "There have been no federal appropriations for cash payments or guarantee subsidies. But in the place of federal funds the government provides considerable unpriced benefits to the enterprises. Government-sponsored enterprises are costly to the government and taxpayers. The benefit is currently worth $6.5 billion annually."[25]

The mortgage crisis from late 2007[edit]

As mortgage originators began to distribute more and more of their loans through private label mortgage-backed securities (MBSs), government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) lost the ability to monitor and control mortgage originators. Competition between the GSEs and private securitizers for loans further undermined GSEs power and strengthened mortgage originators. This contributed to a decline in underwriting standards and was a major cause of the financial crisis.

Investment bank securitizers were more willing to securitize risky loans because they generally retained minimal risk. Whereas the GSEs guaranteed the performance of their MBS, private securitizers generally did not, and might only retain a thin slice of risk.

From 2001 to 2003, financial institutions experienced high earnings due to an unprecedented re-financing boom brought about by historically low interest rates. When interest rates eventually rose, financial institutions sought to maintain their elevated earnings levels with a shift toward riskier mortgages and private label MBS distribution. Earnings depended on volume, so maintaining elevated earnings levels necessitated expanding the borrower pool using lower underwriting standards and new products that the GSEs would not (initially) securitize. Thus, the shift away from GSE securitization to private-label securitization (PLS) also corresponded with a shift in mortgage product type, from traditional, amortizing, fixed-rate mortgages (FRMs) to nontraditional, structurally riskier, nonamortizing, adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs), and in the start of a sharp deterioration in mortgage underwriting standards.[26] The growth of PLS, however, forced the GSEs to lower their underwriting standards in an attempt to reclaim lost market share to please their private shareholders. Shareholder pressure pushed the GSEs into competition with PLS for market share, and the GSEs loosened their guarantee business underwriting standards in order to compete. In contrast, the wholly public FHA/Ginnie Mae maintained their underwriting standards and instead ceded market share.[26]

The growth of private-label securitization and lack of regulation in this part of the market resulted in the oversupply of underpriced housing finance[26] that led, in 2006, to an increasing number of borrowers, often with poor credit, who were unable to pay their mortgages—particularly with adjustable rate mortgages (ARM)—caused a precipitous increase in home foreclosures. As a result, home prices declined as increasing foreclosures added to the already large inventory of homes and stricter lending standards made it more and more difficult for borrowers to get mortgages. This depreciation in home prices led to growing losses for the GSEs, which back the majority of US mortgages. In July 2008, the government attempted to ease market fears by reiterating their view that "Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac play a central role in the US housing finance system". The U.S. Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve took steps to bolster confidence in the corporations, including granting both corporations access to Federal Reserve low-interest loans (at similar rates as commercial banks) and removing the prohibition on the Treasury Department to purchase the GSEs' stock. Despite these efforts, by August 2008, shares of both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had tumbled more than 90% from their one-year prior levels.

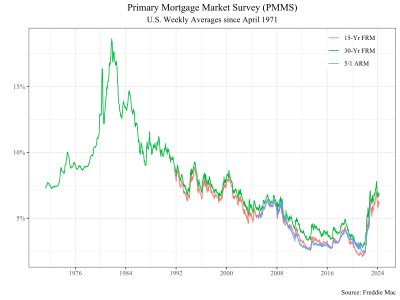

Mortgage rate survey[edit]

Each week Freddie Mac publishes a national average of mortgage rates called the Primary Mortgage Market Survey (PMMS). The PMMS tracks a constant borrower profile of conventional, conforming fully-amortizing home purchase loans with 20% down and excellent credit borrowers.[27] Rates are published for the most popular mortgage products, the 30-year and 15-year fixed-rate. Rates are released each week on Thursdays.

The PMMS began in April 1971 with the 30-year fixed-rate average and the 1-year ARM and 15-year fixed-rate products were added in 1984 and 1991 respectively.[28] In January 2005, the 5/1 hybrid ARM was added and it was discontinued in November 2022.[29] In January 2016, the 1-year ARM was discontinued.

Prior to November 2022, the PMMS collected data by surveying lenders across a proportional mix of lending institutions. Following challenges using a traditional survey approach, Freddie Mac transitioned to replacing lender survey responses with actual loan application data submitted by lenders to Freddie Mac's automated underwriting system. [30] Data is collected from the previous Thursday until the Wednesday before the publication date.

Changes in PMMS rates are widely reported in national media.[31][32][33]

Company[edit]

Leadership[edit]

CEOs (since 1977)[edit]

- Philip R. Brinkerhoff (1977 - August 16, 1982)

- Kenneth J. Thygerson (August 16, 1982 - September 1985)[34][35]

- Leland C. Brendsel* (September 1985 - September 1987)

- Leland C. Brendsel (September 1987 - June 9, 2003)[36]

- Gregory J. Parseghian* (June 9, 2003 - December 2003)[37][38]

- Richard F. Syron (December 2003 - September 6, 2008)[39]

- David M. Moffett (September 7, 2008 - March 13, 2009)[40][41]

- John A. Koskinen* (March 13, 2009 - Aug 2009)[42]

- Charles E. "Ed" Haldeman, Jr. (Aug 2009 - May 21, 2012)[43]

- Donald H. Layton (May 21, 2012 - July 1, 2019)[44]

- David M. Brickman (July 1, 2019 - January 8, 2021)[45][46]

- Vacant (January 8, 2021 - March 16, 2021)

- Mark B. Grier* (March 16, 2021 - June 1, 2021)[47]

- Michael J. Devito (June 1, 2021 - March 15, 2024)[48][49]

- Michael T. Hutchins* (March 16, 2024 - )[50]

* Interim

Awards[edit]

- Freddie Mac was named one of the Best Places to Work for LGBTQ Equality in Human Rights Campaign's 2018 Corporate Equality Index[51]

- Freddie Mac was named one of the 100 Best Companies for Working Mothers in 2004 by Working Mothers magazine.

- Freddie Mac was ranked number 50 in the Fortune 500's 2007 rankings.[52]

- Freddie Mac was ranked number 20 in Forbes's Global 2,000 public companies rankings for 2009.

Credit rating[edit]

As of March 2024.[53]

| Standard & Poor's | Moody's | Fitch | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Senior Long-Term Debt | AA+ | Aaa | AA+ |

| Short-Term Debt | A-1+ | P-1 | F-1+ |

| Preferred Stock | D | Ca | C |

| Outlook | Stable | Negative | Stable |

Investigations[edit]

In 2003, Freddie Mac revealed that it had understated earnings by almost $5 billion, one of the largest corporate restatements in U.S. history. As a result, in November, it was fined $125 million—an amount called "peanuts" by Forbes magazine.[54]

On April 18, 2006, Freddie Mac was fined $3.8 million, by far the largest amount ever assessed by the Federal Election Commission, as a result of illegal campaign contributions. Freddie Mac was accused of illegally using corporate resources between 2000 and 2003 for 85 fundraisers that collected about $1.7 million for federal candidates. Much of the illegal fund raising benefited members of the House Financial Services Committee, a panel whose decisions can affect Freddie Mac. Notably, Freddie Mac held more than 40 fundraisers for House Financial Services Chairman Michael Oxley (R-OH).[55]

Government subsidies and bailout[edit]

Both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac often benefited from an implied guarantee of fitness equivalent to truly federally backed financial groups.[56]

As of 2008, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac owned or guaranteed about half of the U.S.'s $12 trillion mortgage market.[57] This made both corporations highly susceptible to the subprime mortgage crisis of that year. Ultimately, in July 2008, the speculation was made reality, when the US government took action to prevent the collapse of both corporations. The US Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve took several steps to bolster confidence in the corporations, including extending credit limits, granting both corporations access to Federal Reserve low-interest loans (at similar rates as commercial banks), and potentially allowing the Treasury Department to own stock.[58] This event also renewed calls for stronger regulation of GSEs by the government.

President Bush recommended a significant regulatory overhaul of the housing finance industry in 2003, but many Democrats opposed his plan, fearing that tighter regulation could greatly reduce financing for low-income housing, both low- and high-risk.[59] Bush opposed two other acts of legislation:[1][2] Senate Bill S. 190, the Federal Housing Enterprise Regulatory Reform Act of 2005. The bill was sponsored and introduced in the Senate on January 26, 2005 by Senator Chuck Hagel (R–NE) and co-sponsored by Senators Elizabeth Dole (R–NC) and John Sununu (R–NH). The S. 190 bill was reported out of the Senate Banking Committee on July 28, 2005, but never voted on by the full Senate.

On May 23, 2006, the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac regulator, the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight, issued the results of a 27-month-long investigation.[60]

On May 25, 2006, Senator McCain joined as a co-sponsor to the Federal Housing Enterprise Regulatory Reform Act of 2005 (first put forward by Sen. Chuck Hagel)[61] where he pointed out that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac's regulator reported that profits were "illusions deliberately and systematically created by the company's senior management".[62] However, this regulation too met with opposition from both Democrats and Republicans.[63]

Political connections[edit]

Several executives of Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac include Kenneth Duberstein, former Chief of Staff to President Reagan, advisor to John McCain's Presidential Campaign in 2000, and President George W. Bush's transition team leader (Fannie Mae board member 1998–2007);[64] Franklin Raines, former Budget Director for President Clinton, CEO from 1999 to 2004—statements about his role as an advisor to the Obama presidential campaign have been determined to be false;[65] James Johnson, former aide to Democratic Vice-President Walter Mondale and ex-head of Obama's Vice-Presidential Selection Committee, CEO from 1991 to 1998; and Jamie Gorelick, former Deputy Attorney General to President Clinton, and Vice-Chairman from 1998 to 2003. In his position, Johnson earned an estimated $21 million; Raines earned an estimated $90 million; and Gorelick earned an estimated $26 million.[66] Three of these four top executives were also involved in mortgage-related financial scandals.[67][68]

The top 10 recipients of campaign contributions from Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae during the 1989 to 2008 time period include five Republicans and five Democrats. Top recipients of PAC money from these organizations include Roy Blunt (R-MO) $78,500 (total including individuals' contributions $96,950), Robert Bennett (R-UT) $71,499 (total $107,999), Spencer Bachus (R-AL) $70,500 (total $103,300), and Kit Bond (R-MO) $95,400 (total $64,000). The following Democrats received mostly individual contributions from employees, rather than PAC money: Christopher Dodd, (D-CT) $116,900 (but also $48,000 from the PACs), John Kerry, (D-MA) $109,000 ($2,000 from PACs), Barack Obama, (D-IL) $120,349 (only $6,000 from the PACs), Hillary Clinton, (D-NY) $68,050 (only $8,000 from PACs).[69] John McCain received $21,550 from these GSEs during this time, mostly individual money.[70] Freddie Mac also contributed $250,000 to the 2008 Republican National Convention in St. Paul, Minnesota according to FEC filings.[71] The organizers of the Democratic National Convention have not yet submitted their filings on how much they received from Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.[71][needs update]

Conservatorship[edit]

On September 7, 2008, Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) Director James B. Lockhart III announced pursuant to the financial analysis, assessments and statutory authority of the FHFA, he had placed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac under the conservatorship of the FHFA. FHFA has stated that there are no plans to liquidate the company.[5][6]

The announcement followed reports two days earlier that the Federal government was planning to take over Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and had met with their CEOs on short notice.[72][73][74]

The authority of the U.S. Treasury to advance funds for the purpose of stabilizing Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac is limited only by the amount of debt that the entire federal government is permitted by law to commit to. The July 30, 2008, law enabling expanded regulatory authority over Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac increased the national debt ceiling by US$800 billion, to a total of US$10.7 trillion in anticipation of the potential need for the Treasury to have the flexibility to support the federal home loan banks.[75][76][77]

On September 7, 2008, the U.S. government took control of both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Daniel Mudd (CEO of Fannie Mae) and Richard Syron (CEO of Freddie Mac) were replaced. Herbert M. Allison, former vice chairman of Merrill Lynch, took over Fannie Mae, and David M. Moffett, former vice chairman of US Bancorp, took over Freddie Mac.[78]

Related legislation[edit]

This section needs to be updated. (September 2021) |

On May 8, 2013, Representative Scott Garrett introduced the Budget and Accounting Transparency Act of 2014 (H.R. 1872; 113th Congress) into the United States House of Representatives during the 113th United States Congress. The bill, if it were passed, would modify the budgetary treatment of federal credit programs, such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.[79] The bill would require that the cost of direct loans or loan guarantees be recognized in the federal budget on a fair-value basis using guidelines set forth by the Financial Accounting Standards Board.[79] The changes made by the bill would mean that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were counted on the budget instead of considered separately and would mean that the debt of those two programs would be included in the national debt.[80] These programs themselves would not be changed, but how they are accounted for in the United States federal budget would be. The goal of the bill is to improve the accuracy of how some programs are accounted for in the federal budget.[81]

See also[edit]

- Agency security

- Maxine B. Baker – President and CEO of the Freddie Mac Foundation, 1997–present

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

- Derivative (finance)

- Fannie Mae

- Farm Credit System

- Farmer Mac

- Ginnie Mae

- Government sponsored enterprise

- David Kellermann – late CFO of Freddie Mac

- Mortgage law

- Mortgage loan

- Sallie Mae

- Securitization

- USA Funds

References[edit]

- ^ "Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation 2022 Annual Report (Form 10-K)" (PDF). February 22, 2023. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ "Lance F. Drummond Elected Chair of Freddie Mac" (Press release). McLean, VA: Freddie Mac. Globe Newswire. November 7, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ "Tysons Corner CDP, Virginia Archived 2011-11-10 at the Wayback Machine". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved on May 7, 2009.

- ^ "Contact Us Archived 2009-05-14 at the Wayback Machine". Freddie Mac. Retrieved on May 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Lockhart III, James B. (September 7, 2008). "Statement of FHFA Director James B. Lockhart". Federal Housing Finance Agency. Archived from the original on September 12, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ a b "Fact Sheet: Questions and Answers on Conservatorship" (PDF). Federal Housing Finance Agency. September 7, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ Goldfarb, Zachary A.; David Cho; Binyamin Appelbaum (September 7, 2008). "Treasury to Rescue Fannie and Freddie: Regulators Seek to Keep Firms' Troubles From Setting Off Wave of Bank Failures". The Washington Post. pp. A01. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ Christie, Rebecca (September 7, 2008). "Paulson Engineers U.S. Takeover of Fannie, Freddie (Update4)". Bloomberg. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- ^ Adler, Lynn (June 16, 2010). "Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac to delist shares on NYSE". Reuters. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Grynbaum, Michael; Jolly, David (September 8, 2008). "U.S. Takeover of Mortgage Giants Lifts Stock Markets". The New York Times. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ "Freddie Mac". Fortune. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ Olegario, Rowena (2019-05-23). "The History of Credit in America". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.625. ISBN 978-0-19-932917-5.

- ^ Pandit, B. L. (2015). The Global Financial Crisis and the Indian Economy. Delhi/Dordrecht: Springer. p. 11. ISBN 978-81-322-2394-8.

- ^ Wiley Securities Industry Essentials Exam Review 2022. John Wiley & Sons. 2022. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-119-89339-4.

- ^ Dodaro, Gene L. (2010). Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac: Analysis of Options for Revising the Housing Enterprises' Long-Term Structures. Washington, D.C.: DIANE Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4379-2212-7.

- ^ Hoffmann, Susan M.; Cassell, Mark K. (2010). Mission Expansion in the Federal Home Loan Bank System. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-4384-3343-1.

- ^ Leonnig, Carol D. (June 10, 2008). "How HUD Mortgage Policy Fed The Crisis". The Washington Post.

- ^ "History of Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac Conservatorships | Federal Housing Finance Agency". www.fhfa.gov. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Lemke, Lins and Picard, Mortgage-Backed Securities, Chapters 2 and 4 (Thomson West, 2013 ed.).

- ^ "Conforming Loan Limit". FHFA. Archived from the original on March 15, 2014. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ "Freddie Mac Debt Securities: Freddie Notes FAQ". Freddiemac.com. Archived from the original on July 5, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ Vernon L. Smith, "The Clinton Housing Bubble", The Wall Street Journal, December 18, 2007, pA20

- ^ The Economist, "Fannie and Freddie ride again", July 5, 2007

- ^ "CBO TESTIMONY Statement of Dan L. Crippen Director, Federal Subsidies for the Housing GSEs before the Subcommittee on Capital Markets, Insurance, and Government Sponsored Enterprises Committee on Financial Services U.S. House of Representatives, May 23, 2001". Cbo.gov. May 23, 2001. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ Congressional Budget Office, Assessing the Public Costs and Benefits of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, May 1996

- ^ a b c Levitin, Adam J.; Wachter, Susan M. (April 12, 2012). "Explaining the Housing Bubble". Georgetown Law Journal. SSRN 1669401.

- ^ "Freddie Mac's Mortgage Rate Survey Explained". Freddie Mac. 2019-06-14. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions: The Newly Enhanced Primary Mortgage Market Survey". Freddie Mac. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ "About". Freddie Mac. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ "Freddie Mac's Newly Enhanced Mortgage Rate Survey Explained". Freddie Mac. 2022-11-03. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ Colomer, Nora (2024-03-22). "Mortgage rates crawl toward 7% but market optimistic: Freddie Mac". Fox Business. FOX News Network. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ Veiga, Alex (2024-03-21). "Average long-term US mortgage rate climbs back to nearly 7% after two-week slide". AP News. The Associated Press. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ Bahney, Anna (2024-03-07). "Mortgage rates drop after climbing for four weeks". CNN Business. Cable News Network (CNN). Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ "Thrift Officer Thygerson To Head Freddie Mac". The Washington Post. August 3, 1982. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Gilpin, Kenneth; Purdum, Todd (September 4, 1985). "Freddie Mac President Will Head Imperial". The New York Times. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "FREDDIE MAC FINALLY GETS A PERMANENT PRESIDENT". The Washington Post. September 13, 1987. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Day, Kathleen (August 22, 2003). "Freddie Mac CEO To Step Down". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Day, Kathleen (December 7, 2003). "Freddie Mac Names New CEO". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Barr, Colin (September 7, 2008). "Paulson readies the 'bazooka'". CNN Money. CNN. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Dash, Eric (September 7, 2008). "A Former Finance Chief Takes the Reins at Freddie Mac". The New York Times. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Aaron (March 2, 2009). "Freddie Mac CEO to resign". CNN Money. CNN. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "Charles E. Haldeman Jr. is New CEO of Freddie Mac". Multi-Housing News. July 21, 2009. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "Freddie Mac names top executive". ABC News. July 21, 2009. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "Donald H. Layton Named CEO of Freddie Mac". PR Newswire. Freddie Mac. May 10, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "Donald H. Layton to Retire as CEO of Freddie Mac; David M. Brickman Named as Successor" (Press release). McLean, VA: Freddie Mac. Globe Newswire. March 21, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Kleimann, James (November 13, 2020). "David Brickman to step down from Freddie Mac". Housingwire. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "Freddie Mac Names Mark B. Grier as Interim CEO" (Press release). McLean, VA: Freddie Mac. Globe Newswire. March 16, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "Freddie Mac Announces Michael J. DeVito as CEO" (Press release). McLean, VA: Freddie Mac. Globe Newswire. March 26, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "Freddie Mac Announces Michael J. DeVito to Retire as CEO" (Press release). McLean, VA: Freddie Mac. Globe Newswire. September 8, 2023. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "Freddie Mac Announces Michael T. Hutchins as Interim CEO" (Press release). McLean, VA: Freddie Mac. Globe Newswire. March 15, 2024. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ "Best Places to Work 2018". Human Rights Campaign. Archived from the original on November 12, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ "Fortune 500 2007 - Freddie Mac". Fortune. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ "Credit Ratings - Freddie Mac". Freddiemac.com. n.d. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- ^ "Shaking Steady Freddie". Forbes. December 11, 2003.

- ^ "Freddie Mac pays record $3.8 million fine". NBC News. April 18, 2006. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ Goodman, Wes; Shenn, Jody (February 20, 2009). "Fannie Mae Rescue Hindered as Asians Seek Guarantee (Update2)". Bloomberg. Retrieved February 20, 2009.

- ^ Duhigg, Charles, "Loan-Agency Woes Swell From a Trickle to a Torrent", The New York Times, Friday, July 11, 2008

- ^ Luhby, Tami, [1], CNN Money, July 14, 2008

- ^ Labaton, Steven (September 11, 2003). "New Agency Proposed to Oversee Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2009.

- ^ "Report of the Special Examination of Fannie Mae May 2006" (PDF). Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight. May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 16, 2008.

- ^ govtrack.us [dead link]

- ^ govtrack.us, May 25, 2006 Archived October 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Associated Press, Oct 20, 2008". NBC News. October 19, 2008. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ PEU Report/State of the Division (September 19, 2008). "State of the Division: Knowing McCain's Ken Duberstein". Stateofthedivision.blogspot.com. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ "The Washington Post, Sept 19, 2008". Voices.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ "NationalPost, Jul 11, 2008". Retrieved October 20, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "The Washington Post, Apr 6, 2005". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ The New York Times, April 19, 2008

- ^ OpenSecrets.org

- ^ Lindsay Renick Mayer (September 11, 2008). "OpenSecrets.org, Sep 11, 2008". Opensecrets.org. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Yahoo! News Archived October 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hilzenrath, David S.; Zachary A. Goldfarb (September 5, 2008). "Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac to be Put Under Federal Control, Sources Say". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- ^ Labaton, Stephen; Andres Ross Sorkin (September 5, 2008). "U.S. Rescue Seen at Hand for 2 Mortgage Giants". The New York Times. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- ^ Hilzenrath, David S.; Neil Irwin; Zachary A. Goldfarb (September 6, 2008). "U.S. Nears Rescue Plan For Fannie And Freddie Deal Said to Involve Change of Leadership, Infusions of Capital". The Washington Post. pp. A1. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David (July 27, 2008). "Congress Sends Housing Relief Bill to President". The New York Times. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David M. (July 31, 2008). "Bush Signs Sweeping Housing Bill". The New York Times. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- ^ See HR 3221, signed into law as Public Law 110-289: A bill to provide needed housing reform and for other purposes.

Access to Legislative History: Library of Congress THOMAS: A bill to provide needed housing reform and for other purposes. Archived 2008-09-18 at the Wayback Machine

White House pre-signing statement: Statement of Administration Policy: H.R. 3221 – Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 Archived November 30, 2020, at the Wayback Machine (July 23, 2008). Executive office of the President, Office of Management and Budget, Washington DC. - ^ Ellis, David. "U.S. seizes Fannie and Freddie". CNN Money. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ a b "H.R. 1872 - CBO" (PDF). United States Congress. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ Kasperowicz, Pete (March 28, 2014). "House to push budget reforms next week". The Hill. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- ^ Kasperowicz, Pete (April 4, 2014). "Next week: Bring out the budget". The Hill. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

Further reading[edit]

- "Housing Policy and Debate" (PDF). Fannie Mae, Office of Housing Policy Research, Washington, DC.

- Labaton, Stephen; Weisman, Steven R. (July 11, 2008). "U.S. Weighs Takeover of Two Mortgage Giants". The New York Times.

- Lemke, Thomas P.; Lins, Gerald T.; Picard, Marie E. (2013). Mortgage-Backed Securities. Thomson West.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Business data for Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation:

- Affordable housing

- Mortgage industry of the United States

- Mortgage industry companies of the United States

- American companies established in 1970

- Financial services companies established in 1970

- Companies formerly listed on the New York Stock Exchange

- United States government-sponsored enterprises

- 1970 in economic history

- Companies traded over-the-counter in the United States

- Companies based in McLean, Virginia