Gin

A selection of bottled gins for sale in Georgia, United States, 2010 | |

| Type | Distilled alcoholic drink |

|---|---|

| Introduced | 13th century |

| Alcohol by volume | 35–60% |

| Proof (US) | 70–140° |

| Colour | Clear |

| Ingredients | Barley or other grain, juniper berries |

| Related products | Jenever |

Gin (/dʒɪn/) is a distilled alcoholic drink flavoured with juniper berries and other botanical ingredients.[1][2]

Gin originated as a medicinal liquor made by monks and alchemists across Europe. The modern gin was modified in Flanders and the Netherlands to provide aqua vita from distillates of grapes and grains, becoming an object of commerce in the spirits industry. Gin became popular in England after the introduction of jenever, a Dutch and Belgian liquor. Although this development had been taking place since the early 17th century, gin became widespread after the 1688 Glorious Revolution led by William of Orange and subsequent import restrictions on French brandy. Gin emerged as the national alcoholic drink of England during the so-called Gin Craze of 1695–1735.

Gin is produced from a wide range of herbal ingredients in a number of distinct styles and brands. After juniper, gin tends to be flavoured with herbs, spices, floral or fruit flavours, or often a combination. It is commonly mixed with tonic water in a gin and tonic. Gin is also used as a base spirit to produce flavoured, gin-based liqueurs, for example sloe gin, traditionally produced by the addition of fruit, flavourings and sugar.

Etymology[edit]

The name gin is a shortened form of the older English word genever,[3] related to the French word genièvre and the Dutch word jenever. All ultimately derive from juniperus, the Latin for juniper.[4]

History[edit]

Origin: 13th-century mentions[edit]

The earliest known written reference to jenever appears in the 13th-century encyclopaedic work Der Naturen Bloeme (Bruges), with the earliest printed recipe for jenever dating from 16th-century work Een Constelijck Distileerboec (Antwerp).

The monks used it to distill sharp, fiery, alcoholic tonics, one of which was distilled from wine infused with juniper berries. They were making medicines, hence the juniper. As a medicinal herb, juniper had been an essential part of doctors' kits for centuries: the Romans burned juniper branches for purification, and plague doctors stuffed the beaks of their plague masks with juniper to supposedly protect them from the Black Death. Across Europe, apothecaries handed out juniper tonic wines for coughs, colds, pains, strains, ruptures and cramps. These were a popular cure-all, though some thought these tonic wines to be a little too popular, and consumed for enjoyment rather than medicinal purposes.[5][further explanation needed][better source needed]

17th century[edit]

The physician Franciscus Sylvius has been falsely credited with the invention of gin in the mid-17th century,[6] as the existence of jenever is confirmed in Philip Massinger's play The Duke of Milan (1623), when Sylvius would have been about nine years old. It is further claimed that English soldiers who provided support in Antwerp against the Spanish in 1585, during the Eighty Years' War, were already drinking jenever for its calming effects before battle, from which the term Dutch courage is believed to have originated.[7][8]

By the mid-17th century, numerous small Dutch and Flemish distillers had popularized the re-distillation of malted barley spirit or malt wine with juniper, also anise, caraway, coriander, etc.,[9] which were sold in pharmacies and used to treat such medical problems as kidney ailments, lumbago, stomach ailments, gallstones, and gout. Gin emerged in England in varying forms by the early 17th century, and at the time of the Stuart Restoration, enjoyed a brief resurgence. Gin became vastly more popular as an alternative to brandy, when William III and Mary II became co-sovereigns of England, Scotland and Ireland after leading the Glorious Revolution.[10] Particularly in crude, inferior forms, it was more likely to be flavoured with turpentine.[11] Historian Angela McShane has described it as a "Protestant drink" as its rise was brought about by a Protestant king, fuelling his armies fighting the Catholic Irish and French.[12]

18th century[edit]

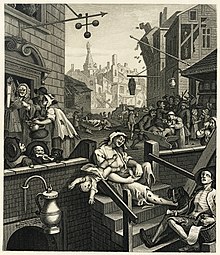

Gin drinking in England rose significantly after the government allowed unlicensed gin production, and at the same time imposed a heavy duty on all imported spirits such as French brandy. This created a larger market for poor-quality barley that was unfit for brewing beer, and in 1695–1735 thousands of gin-shops sprang up throughout England, a period known as the Gin Craze.[13] Because of the low price of gin compared with other drinks available at the time and in the same location, gin began to be consumed regularly by the poor.[14] Of the 15,000 drinking establishments in London, not including coffee shops and drinking chocolate shops, over half were gin shops. Beer maintained a healthy reputation as it was often safer to drink the brewed ale than unclean plain water.[15] Gin, though, was blamed for various social problems, and it may have been a factor in the higher death rates which stabilized London's previously growing population.[10] The reputation of the two drinks was illustrated by William Hogarth in his engravings Beer Street and Gin Lane (1751), described by the BBC as "arguably the most potent anti-drug poster ever conceived".[16] The negative reputation of gin survives in the English language in terms like gin mills or the American phrase gin joints to describe disreputable bars, or gin-soaked to refer to drunks. The epithet mother's ruin is a common British name for gin, the origin of which is debated.[17]

The Gin Act 1736 imposed high taxes on retailers and led to riots in the streets. The prohibitive duty was gradually reduced and finally abolished in 1742. The Gin Act 1751 was more successful, but it forced distillers to sell only to licensed retailers and brought gin shops under the jurisdiction of local magistrates.[10] Gin in the 18th century was produced in pot stills, and thus had a maltier profile than modern London gin.[18]

In London in the early 18th century, much gin was distilled legally in residential houses (there were estimated to be 1,500 residential stills in 1726) and was often flavoured with turpentine to generate resinous woody notes in addition to the juniper.[19] As late as 1913, Webster's Dictionary states without further comment, "'common gin' is usually flavoured with turpentine".[11]

Another common variation was to distill in the presence of sulfuric acid. Although the acid itself does not distil, it imparts the additional aroma of diethyl ether to the resulting gin. Sulfuric acid subtracts one water molecule from two ethanol molecules to create diethyl ether, which also forms an azeotrope with ethanol, and therefore distils with it. The result is a sweeter spirit, and one that may have possessed additional analgesic or even intoxicating effects – see Paracelsus.[citation needed]

Dutch or Belgian gin, also known as jenever or genever, evolved from malt wine spirits, and is a distinctly different drink from later styles of gin. Schiedam, a city in the province of South Holland, is famous for its jenever-producing history. The same for Hasselt in the Belgian province of Limburg. The oude (old) style of jenever remained very popular throughout the 19th century, where it was referred to as Holland or Geneva gin in popular, American, pre-Prohibition bartender guides.[20]

The 18th century gave rise to a style of gin referred to as Old Tom gin, which is a softer, sweeter style of gin, often containing sugar. Old Tom gin faded in popularity by the early 20th century.[18]

19th–20th centuries[edit]

The invention and development of the column still (1826 and 1831)[21] made the distillation of neutral spirits practical, thus enabling the creation of the "London dry" style that evolved later in the 19th century.[22]

In tropical British colonies gin was used to mask the bitter flavour of quinine, which was the only effective anti-malarial compound. Quinine was dissolved in carbonated water to form tonic water; the resulting cocktail is gin and tonic, although modern tonic water contains only a trace of quinine as a flavouring. Gin is a common base spirit for many mixed drinks, including the martini. Secretly produced "bathtub gin" was available in the speakeasies and "blind pigs" of Prohibition-era America as a result of the relatively simple production.[23]

Sloe gin is traditionally described as a liqueur made by infusing sloes (the fruit of the blackthorn) in gin, although modern versions are almost always compounded from neutral spirits and flavourings. Similar infusions are possible with other fruits, such as damsons. Another popular gin-based liqueur with a longstanding history is Pimm's No.1 Cup (25% alcohol by volume (ABV)), which is a fruit cup flavoured with citrus and spices.[citation needed]

The National Jenever Museums are located in Hasselt in Belgium, and Schiedam in the Netherlands.[24]

21st century[edit]

Since 2013, gin has been in a period of ascendancy worldwide,[25] with many new brands and producers entering the category leading to a period of strong growth, innovation and change. More recently gin-based liqueurs have been popularised, reaching a market outside that of traditional gin drinkers, including fruit-flavoured and usually coloured "Pink gin",[26] rhubarb gin, Spiced gin, violet gin, blood orange gin and sloe gin. Surging popularity and unchecked competition has led to consumer's conflation of gin with gin liqueurs and many products are straddling, pushing or breaking the boundaries of established definitions in a period of genesis for the industry.

Legal definition[edit]

Geographical indication[edit]

Some legal classifications (protected denomination of origin) define gin as only originating from specific geographical areas without any further restrictions (e.g. Plymouth gin (PGI now lapsed), Ostfriesischer Korngenever, Slovenská borovička, Kraški Brinjevec, etc.), while other common descriptors refer to classic styles that are culturally recognised, but not legally defined (e.g. Old Tom gin). Sloe gin is also worth mentioning, as although technically a gin-based liqueur, it is unique in that the EU spirit drink regulations stipulate the colloquial term "sloe gin" can legally be used without the "liqueur" suffix when certain production criteria are met.[citation needed]

Canada[edit]

According to the Canadian Food and Drug Regulation, gin is produced through redistillation of alcohol from juniper berries or a mixture of more than one such redistilled food products.[27] The Canadian Food and Drug Regulation recognises gin with three different definitions (Genever, Gin, London or Dry gin) that loosely approximate the US definitions. Whereas a more detailed regulation is provided for Holland gin or genever, no distinction is made between compounded gin and distilled gin. Either compounded or distilled gin can be labelled as Dry Gin or London Dry Gin if it does not contain any sweetening agents.[28][29] For Genever and Gin, they shall not contain more than two percent sweetening agents.[28][29]

European Union[edit]

Although many different styles of gin have evolved, it is legally differentiated into four categories in the European Union, as follows.[1]

Juniper-flavoured spirit drink[edit]

Juniper-flavoured spirit drinks include the earliest class of gin, which is produced by pot distilling a fermented grain mash to moderate strength, e.g., 68% ABV, and then redistilling it with botanicals to extract the aromatic compounds. It must be bottled at a minimum of 30% ABV. Juniper-flavoured spirit-drinks may also be sold under the names Wacholder or Ginebra.

Gin[edit]

Gin is a juniper-flavoured spirit made not via the redistillation of botanicals, but by simply adding approved natural flavouring substances to a neutral spirit of agricultural origin. The predominant flavour must be juniper. Minimum bottled strength is 37.5% ABV.

Distilled gin[edit]

Distilled gin is produced exclusively by redistilling ethanol of agricultural origin with an initial strength of 96% ABV (the azeotrope of water and ethanol), in the presence of juniper berries and of other natural botanicals, provided that the juniper taste is predominant. Gin obtained simply by adding essences or flavourings to ethanol of agricultural origin is not distilled gin. Minimum bottled strength is 37.5% ABV.

London gin[edit]

London gin is obtained exclusively from ethanol of agricultural origin with a maximum methanol content of 5 g (0.18 oz) per hectolitre of 100% ABV equivalent, whose flavour is introduced exclusively through the re-distillation in traditional stills of ethanol in the presence of all the natural plant materials used, the resultant distillate of which is at least 70% ABV. London gin may not contain added sweetening exceeding 0.1 g (0.0035 oz) of sugars per litre of the final product, nor colourants, nor any added ingredients other than water. The predominant flavour must be juniper. The term London gin may be supplemented by the term dry. Minimum bottled strength is 37.5% ABV.

United States[edit]

In the United States of America, "gin" is defined as an alcoholic beverage of no less than 40% ABV (80 proof) that possesses the characteristic flavour of juniper berries. Gin produced only through the redistillation of botanicals can be further distinguished and marketed as "distilled gin".[2]

Production[edit]

Methods[edit]

Gin can be broadly differentiated into three basic styles reflecting modernization in its distillation and flavouring techniques:[30]

Pot distilled gin represents the earliest style of gin, and is traditionally produced by pot distilling a fermented grain mash (malt wine) from barley or other grains, then redistilling it with flavouring botanicals to extract the aromatic compounds. A double gin can be produced by redistilling the first gin again with more botanicals. Due to the use of pot stills, the alcohol content of the distillate is relatively low; around 68% ABV for a single distilled gin or 76% ABV for a double gin. This type of gin is often aged in tanks or wooden casks, and retains a heavier, malty flavour that gives it a marked resemblance to whisky. Korenwijn (grain wine) and the oude (old) style of Geneva gin or Holland gin represent the most prominent gins of this class.[30]

Column distilled gin evolved following the invention of the Coffey still, and is produced by first distilling high proof (e.g. 96% ABV) neutral spirits from a fermented mash or wash using a refluxing still such as a column still. The fermentable base for this spirit may be derived from grain, sugar beets, grapes, potatoes, sugar cane, plain sugar, or any other material of agricultural origin. The highly concentrated spirit is then redistilled with juniper berries and other botanicals in a pot still. Most often, the botanicals are suspended in a "gin basket" positioned within the head of the still, which allows the hot alcoholic vapours to extract flavouring components from the botanical charge.[31] This method yields a gin lighter in flavour than the older pot still method, and results in either a distilled gin or London dry gin,[30] depending largely upon how the spirit is finished.

Compound gin is made by compounding (blending) neutral spirits with essences, other natural flavourings, or ingredients left to infuse in neutral spirit without redistillation.

Flavouring[edit]

Popular botanicals or flavouring agents for gin, besides the required juniper, often include citrus elements, such as lemon and bitter orange peel, as well as a combination of other spices, which may include any of anise, angelica root and seed, orris root, cardamom, pine needles and cone, licorice root, cinnamon, almond, cubeb, savory, lime peel, grapefruit peel, dragon eye (longan), saffron, baobab, frankincense, coriander, grains of paradise, nutmeg, cassia bark or others. The different combinations and concentrations of these botanicals in the distillation process cause the variations in taste among gin products.[32][33]

Chemical research has begun to identify the various chemicals that are extracted in the distillation process and contribute to gin's flavouring. For example, juniper monoterpenes come from juniper berries. Citric and berry flavours come from chemicals such as limonene and gamma-terpinene linalool found in limes, blueberries and hops amongst others. Floral notes come from compounds such as geraniol and euganol. Spice-like flavours come from chemicals such as sabinene, delta-3-carene, and para-cymene.[34]

In 2018, more than half the growth in the UK Gin category was contributed by flavoured gin.[35]

Consumption[edit]

Classic gin cocktails[edit]

A well known gin cocktail is the martini, traditionally made with gin and dry vermouth. Several other notable gin-based drinks include:

Notable brands[edit]

- Archie Rose Distilling Co. – Sydney microdistillery

- Aviation American Gin – Oregon, US, one of the early New Western style gins

- Beefeater – England, first produced in 1820

- BOLS Damrak – Netherlands, jenever

- The Botanist – Hebridean island of Islay, Scotland, made with 31 botanicals, 22 being native to the island

- Blackwood's – Scotland

- Bombay Sapphire – England, distilled with ten botanicals

- Boodles British Gin – England

- Booth's Gin – England

- Broker's Gin – England

- Catoctin Creek – organic gin from Virginia, US

- Citadelle – France

- Cork Dry Gin – Ireland

- Gilbey's – England

- Gilpin's Westmorland Extra Dry Gin – England

- Ginebra San Miguel – Philippines

- Gordon's – England, first distilled in 1763

- Greenall's – England

- Hendrick's Gin – Scotland, infused with flavours of cucumber and rose petal

- Konig's Westphalian Gin – Germany

- Leopolds Gin – Colorado, US

- Masons Gin – North Yorkshire, England

- Nicholson's – England, made in London from 1730

- Plymouth – England, first distilled in 1793

- Pickering's Gin – Scotland, from Edinburgh's first gin distillery in 150 years

- Sacred Microdistillery – England, from one of London's new micro-distilleries

- Seagram's – Quebec, Canada

- Sipsmith – England

- Smeets – Belgium, jenever

- Steinhäger – Germany

- St. George – California, US

- Taaka – Louisiana, US

- Tanqueray – England, first distilled in 1830

- Uganda Waragi – Uganda, triple distilled Waragi

- Vickers – South Australia

- Whitley Neill Gin – England

See also[edit]

- Gin palace – Gin-selling establishment

- List of cocktails

- List of drinks

References[edit]

- ^ a b E.U. Definitions of Categories of Alcoholic Beverages 2019/787, M(b), 2019

- ^ a b Definitions ("Standards of Identity") for Distilled Spirits, Title 27 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, Chapter 1, Part 5, Section 5.22 ,(c) Class 3

- ^ "Gin". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- ^ For etymology of genever, see "Genever". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2019-12-21.. For genièvre, see "Genièvre". Ortolang (in French). CNRTL. Retrieved 2018-10-13.. For jenever, see De Vries, Jan (1997). "Jenever". Nederlands Etymologisch Woordenboek (in Dutch). Brill. p. 286. ISBN 978-90-04-08392-9. Retrieved 2018-10-13..

- ^ The scandalous history of gin: the story behind everyone's favourite spirit, retrieved 1 January 2021

- ^ Gin, tasteoftx.com, archived from the original on 16 April 2009, retrieved 5 April 2009

- ^ Van Acker - Beittel, Veronique (June 2013), Genever: 500 Years of History in a Bottle, Flemish Lion, ISBN 978-0-615-79585-0

- ^ Origins of Gin, Bluecoat American Dry Gin, archived from the original on 13 February 2009, retrieved 5 April 2009

- ^ Forbes, R. J. (1997). A Short History of the Art of Distillation from the Beginnings up to the Death of Cellier Blumenthal. Brill Academic Publishers.

- ^ a b c Brownlee, Nick (2002). "3 – History". This is alcohol. Sanctuary Publishing. pp. 84–93. ISBN 978-1-86074-422-8.

- ^ a b "Gin (definition)". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Bragg, Melvyn; Tillotson, Simon. (2018). In Our Time : the companion. [Place of publication not identified]: Simon & Schuster Ltd. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4711-7449-0. OCLC 1019622766.

- ^ "The Gin Craze, In Our Time - BBC Radio 4". BBC.

- ^ Defoe, Daniel (1727). The Complete English Tradesman: In Familiar Letters; Directing Him in All the Several Parts and Progressions of Trade ... Calculated for the Instruction of Our Inland Tradesmen; and Especially of Young Beginners. Charles Rivington.

... the Distillers have found out a way to hit the palate of the Poor, by their new fashion'd compound Waters called Geneva

- ^ White, Matthew. "Health, Hygiene and the Rise of 'Mother Gin' in the 18th Century". Georgian Britain. British Library. Archived from the original on 28 April 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Rohrer, Finlo (28 July 2014). "When gin was full of sulphuric acid and turpentine". Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ "Origin of the phrase "mother's ruin?"". English Language and Usage. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ a b Martin, Scott C. (2014-12-16). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Alcohol: Social, Cultural, and Historical Perspectives. SAGE Publications. p. 613. ISBN 978-1-4833-3108-9.

- ^ "Distil my beating heart". The Guardian. London. 1 June 2002. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Johnson, Harry; "Harry Johnson's New and Improved Bartender's Manual; 1900.";

- ^ "Coffey still – Patent Still – Column Still: a continuous distillation". StillCooker & Friends. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ Sheppard, Julie (2021-01-21). "What is London Dry gin? Ask Decanter". Decanter. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ Jenkins, Moses (2019). Gin: A Short History. Bloomsbury. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-1784423438.

- ^ "Nationaal Jenevermuseum Hasselt (Hasselt) - Visitor Information & Reviews - WhichMuseum". whichmuseum.com. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ^ "Google Trends". Google Trends. Archived from the original on 2021-12-15. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

- ^ Naylor, Tony (2018-12-06). "Pink gin is booming – but here's why many purists loathe it". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

- ^ Branch, Legislative Services (2 March 2022). "Consolidated federal laws of canada, Food and Drug Regulations". laws.justice.gc.ca.

- ^ a b "Food and Drug Regulations (C.R.C., c. 870)". Justice Laws Website - Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Canada Food and Drug Regulations (C.R.C., c. 870, B.18.001)". Justice Laws Website - Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Buglass, Alan J. (2011), "3.4", Handbook of Alcoholic Beverages: Technical, Analytical and Nutritional Aspects, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., ISBN 978-0-470-51202-9

- ^ "Home Distillation of Alcohol (Homemade Alcohol to Drink)". Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Newman, Kara (9 May 2017). "Gin Botanicals, Decoded". Wine Enthusiast. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Hines, Nick (25 October 2017). "The 10 Most Popular Botanicals in Gin, Explained". VinePair. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Riu-Aumatell, M.; Vichi, S.; Mora-Pons, M.; López-Tamames, E.; Buxaderas, S. (2008-08-01). "Sensory Characterization of Dry Gins with Different Volatile Profiles". Journal of Food Science. 73 (6): S286–S293. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00820.x. ISSN 1750-3841. PMID 19241573.

- ^ "Flavoured gin contributes over 50% of the growth in sector". 21 December 2018.

Further reading[edit]

- Deegan, Grant (1999). "From the Bathtub to the Boardroom: Gin and Its History". MY2K: Martini 2000. 1 (1). Archived from the original on 2004-10-22.

- Dillon, Patrick (2002). The Much-Lamented Death of Madam Geneva: The Eighteenth-Century Gin Craze. London: Headline Review. ISBN 978-0-7472-3545-3.

- Williams, Olivia (2015). Gin Glorious Gin: How Mother's Ruin Became the Spirit of London. London: Headline. ISBN 978-1-4722-1534-5.

External links[edit]

- EU definition original source – scroll down to paras: 20 nand 21 of Annex II – Spirit Drinks

- Gin news page – Alcohol and Drugs History Society

- Gin Palaces at The Dictionary of Victorian London

- New Western Style Gins at .drinkspirits.com

- Map of Scottish Gin Producers Archived 2022-05-08 at the Wayback Machine at ginspiredscotland.com

- History of Gin at Difford's Guide