Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village | |

|---|---|

Bird's eye view of Greenwich Village, facing towards the skyline of Lower Manhattan | |

Location in New York City | |

| Coordinates: 40°44′01″N 74°00′10″W / 40.73361°N 74.00278°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City | New York City |

| Borough | Manhattan |

| Community District | Manhattan 2[1] |

| Named for | Groenwijck (Green District) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.75 km2 (0.289 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 22,785 |

| • Density | 30,000/km2 (79,000/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Villager |

| Economics | |

| • Median income | $119,728 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 10003, 10011, 10012, 10014[2] |

| Area codes | 212, 332, 646, and 917 |

Greenwich Village Historic District | |

453–461 Sixth Avenue in the Historic District | |

| Location | Boundaries: north: W 14th St; south: Houston St; west: Hudson River; east: Broadway |

| Coordinates | 40°44′2″N 74°0′4″W / 40.73389°N 74.00111°W |

| Architectural style | various |

| NRHP reference No. | 79001604[3] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 19, 1979 |

| Designated NYCL | initial district: April 29, 1969 extension: May 2, 2006 second extension: June 22, 2010 |

Greenwich Village,[pron 1] or simply the Village, is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village also contains several subsections, including the West Village west of Seventh Avenue and the Meatpacking District in the northwest corner of Greenwich Village.

Its name comes from Groenwijck, Dutch for "Green District".[4][a] In the 20th century, Greenwich Village was known as an artists' haven, the bohemian capital, the cradle of the modern LGBT movement, and the East Coast birthplace of both the Beat Generation and counterculture of the 1960s. Greenwich Village contains Washington Square Park, as well as two of New York City's private colleges, New York University (NYU) and The New School.[6][7] In later years it has been associated with hipsters.[8][9]

Greenwich Village is part of Manhattan Community District 2, and is patrolled by the 6th Precinct of the New York City Police Department.[1] Greenwich Village has undergone extensive gentrification and commercialization;[10] the four ZIP Codes that constitute the Village – 10011, 10012, 10003, and 10014 – were all ranked among the ten most expensive in the United States by median housing prices in 2014, according to Forbes,[11] with residential property sale prices in the West Village neighborhood typically exceeding US$2,100/sq ft ($23,000/m2) in 2017.[12]

Geography[edit]

Boundaries[edit]

The neighborhood is bordered by Broadway to the east, the North River (part of the Hudson River) to the west, Houston Street to the south, and 14th Street to the north. It is roughly centered on Washington Square Park and New York University. Adjacent to Greenwich Village are the neighborhoods of NoHo and the East Village to the east, SoHo and Hudson Square to the south, and Chelsea and Union Square to the north. The East Village was formerly considered part of the Lower East Side and has never been considered a part of Greenwich Village.[13] The western part of Greenwich Village is known as the West Village; the dividing line of its eastern border is debated but commonly cited as Seventh Avenue or Sixth Avenue. The Far West Village is another sub-neighborhood of Greenwich Village that is bordered on its west by the Hudson River and on its east by Hudson Street.[14]

Into the early 20th century, Greenwich Village was distinguished from the upper-class neighborhood of Washington Square—based on the major landmark of Washington Square Park[15][16] or Empire Ward[17] in the 19th century.

Encyclopædia Britannica's 1956 article on "New York (City)" states (under the subheading "Greenwich Village") that the southern border of the Village is Spring Street, reflecting an earlier understanding. Today, Spring Street overlaps with the modern, newer SoHo neighborhood designation, while the modern Encyclopædia Britannica cites the southern border as Houston Street.[18]

Grid plan[edit]

As Greenwich Village was once a rural, isolated hamlet to the north of the 17th century European settlement on Manhattan Island, its street layout is more organic than the planned grid pattern of the 19th century grid plan (based on the Commissioners' Plan of 1811). Greenwich Village was allowed to keep the 18th century street pattern of what is now called the West Village: areas that were already built up when the plan was implemented, west of what is now Greenwich Avenue and Sixth Avenue, resulted in a neighborhood whose streets are dramatically different, in layout, from the ordered structure of the newer parts of Manhattan.[19]

Many of the neighborhood's streets are narrow and some curve at odd angles. This is generally regarded as adding to both the historic character and charm of the neighborhood. In addition, as the meandering Greenwich Street used to be on the Hudson River shoreline, much of the neighborhood west of Greenwich Street is on landfill, but still follows the older street grid.[19] When Sixth and Seventh Avenues were extended in the early 20th century, they were built diagonally to the existing street plan, and many older, smaller streets had to be demolished.[19]

Unlike the streets of most of Manhattan above Houston Street, streets in the Village are typically named, not numbered. While some of the formerly named streets (including Factory, Herring and Amity Streets) are now numbered, they still do not always conform to the usual grid pattern when they enter the neighborhood.[19] For example, West 4th Street runs east–west across most of Manhattan, but runs north–south in Greenwich Village, causing it to intersect with West 10th, 11th, and 12th Streets before ending at West 13th Street.[19]

A large section of Greenwich Village, made up of more than 50 northern and western blocks in the area up to 14th Street, is part of a Historic District established by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. The District's convoluted borders run no farther south than 4th Street or St. Luke's Place, and no farther east than Washington Square East or University Place.[20] Redevelopment in that area is severely restricted, and developers must preserve the main façade and aesthetics of the buildings during renovation.

Most of the buildings of Greenwich Village are mid-rise apartments, 19th century row houses, and the occasional one-family walk-up, a sharp contrast to the high-rise landscape in Midtown and Downtown Manhattan.

Political representation[edit]

Politically, Greenwich Village is in New York's 10th congressional district.[21][22] It is also in the New York State Senate's 25th district,[23][24] the New York State Assembly's 66th district,[25][26] and the New York City Council's 3rd district.[27]

History[edit]

Early years[edit]

In the 16th century, Lenape referred to its farthest northwest corner, by the cove on the Hudson River at present-day Gansevoort Street, as Sapokanikan ("tobacco field"). The land was cleared and turned into pasture by the Dutch and their enslaved Africans, who named their settlement Noortwyck (also spelled Noortwijck, "North district", equivalent to 'Northwich/Northwick'). In the 1630s, Governor Wouter van Twiller farmed tobacco on 200 acres (0.81 km2) here at his "Farm in the Woods".[28] The English conquered the Dutch settlement of New Netherland in 1664, and Greenwich Village developed as a hamlet separate from the larger New York City to the south on land that would eventually become the Financial District. In 1644, the eleven Dutch African settlers in the area were granted half freedoms after the first Black legal protest in America.[b] All received parcels of land in what is now Greenwich Village,[29] in an area that became known as the Land of the Blacks.

The earliest known reference to the village's name as "Greenwich" dates back to 1696, in the will of Yellis Mandeville of Greenwich; however, the village was not mentioned in the city records until 1713.[30] Sir Peter Warren began accumulating land in 1731 and built a frame house capacious enough to hold sittings of the New York General Assembly when smallpox rendered the city dangerous in 1739 and subsequent years; on one occasion in 1746, the house of Mordecai Gomez was used.[31][32] Warren's house, which survived until the Civil War era, overlooked the North River from a bluff; its site on the block bounded by Perry and Charles Streets, Bleecker and West 4th Streets,[33] can still be recognized by its mid-19th century rowhouses inserted into a neighborhood still retaining many houses of the 1830–37 boom.

Newgate Prison[edit]

From 1797[34] until 1829,[35] the bucolic village of Greenwich was the location of New York State's first penitentiary, Newgate Prison, on the Hudson River at what is now West 10th Street,[34] near the Christopher Street pier.[36] The building was designed by Joseph-François Mangin, who would later co-design New York City Hall.[37] Although the intention of its first warden, Quaker prison reformer Thomas Eddy, was to provide a rational and humanitarian place for retribution and rehabilitation, the prison soon became an overcrowded and pestilent place, subject to frequent riots by the prisoners which damaged the buildings and killed some inmates.[34] By 1821, the prison, designed for 432 inmates, held 817 instead, a number made possible only by the frequent release of prisoners, sometimes as many as 50 a day.[38] Since the prison was north of the New York City boundary at the time, being sentenced to Newgate became known as being "sent up the river". This term became popularized once prisoners started being sentenced to Sing Sing Prison, in the town of Ossining upstream of New York City.[36]

Isaacs-Hendricks House[edit]

The oldest house remaining in Greenwich Village is the Isaacs-Hendricks House, at 77 Bedford Street (built 1799, much altered and enlarged 1836, third story 1928).[39] When the Church of St. Luke in the Fields was founded in 1820, it stood in fields south of the road (now Christopher Street) that led from Greenwich Lane (now Greenwich Avenue) down to a landing on the North River. In 1822, a yellow fever epidemic in New York encouraged residents to flee to the healthier air of Greenwich Village, and afterwards many stayed. The future site of Washington Square was a potter's field from 1797 to 1823 when up to 20,000 of New York's poor were buried here, and still remain. The handsome Greek revival rowhouses on the north side of Washington Square were built about 1832, establishing the fashion of Washington Square and lower Fifth Avenue for decades to come. Well into the 19th century, the district of Washington Square was considered separate from Greenwich Village.

In 1825, the Commercial Advertiser was writing that "Greenwich is no longer a country village. Such has been the growth of our city that the building of one block more will connect the two places" of Greenwich and New York.[40] By 1850, the city had developed entirely around Greenwich Village such that the two were no longer considered separate.

Reputation as urban bohemia[edit]

Greenwich Village historically was known as an important landmark on the map of American bohemian culture in the early and mid-20th century. The neighborhood was known for its colorful, artistic residents and the alternative culture they propagated. Due in part to the progressive attitudes of many of its residents, the Village was a focal point of new movements and ideas, whether political, artistic, or cultural. This tradition as an enclave of avant-garde and alternative culture was established during the 19th century and continued into the 20th century, when small presses, art galleries, and experimental theater thrived. In 1969, enraged members of the gay community, in search for equality, started the Stonewall riots. The Stonewall Inn was later recognized as a National Historic Landmark for having been the location where the gay rights movement originated.[41][42][43] On June 27, 2019, the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor was inaugurated at the Stonewall Inn.[44]

The Tenth Street Studio Building was situated at 51 West 10th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. The building was commissioned by James Boorman Johnston[c] and designed by Richard Morris Hunt. Its innovative design soon represented a national architectural prototype, and featured a domed central gallery, from which interconnected rooms radiated. Hunt's studio within the building housed the first architectural school in the United States. Soon after its completion in 1857, the building helped to make Greenwich Village central to the arts in New York City, drawing artists from all over the country to work, exhibit, and sell their art. In its initial years Winslow Homer took a studio there,[46] as did Edward Lamson Henry, and many of the artists of the Hudson River School, including Frederic Church and Albert Bierstadt.[47]

From the late 19th century until the present, the Hotel Albert has served as a cultural icon of Greenwich Village. Opened during the 1880s and originally located at 11th Street and University Place, called the Hotel St. Stephan and then, after 1902, called the Hotel Albert while under the ownership of William Ryder, it served as a meeting place, restaurant and dwelling for several important artists and writers from the late 19th century well into the 20th century. After 1902, the owner's brother Albert Pinkham Ryder lived and painted there. Some other noted guests who lived there include: Augustus St. Gaudens, Robert Louis Stevenson, Mark Twain, Hart Crane, Walt Whitman, Anaïs Nin, Thomas Wolfe, Robert Lowell, Horton Foote, Salvador Dalí, Philip Guston, Jackson Pollock, and Andy Warhol.[48][49] During the golden age of bohemianism, Greenwich Village became famous for such eccentrics as Joe Gould (profiled at length by Joseph Mitchell) and Maxwell Bodenheim, dancer Isadora Duncan, writer William Faulkner, and playwright Eugene O'Neill. Political rebellion also made its home here, whether serious (John Reed) or frivolous (Marcel Duchamp and friends set off balloons from atop Washington Square Arch, proclaiming the founding of "The Independent Republic of Greenwich Village" on January 24, 1917).[50][51]

In 1924, the Cherry Lane Theatre was established. Located at 38 Commerce Street, it is New York City's oldest continuously running Off-Broadway theater. A landmark in Greenwich Village's cultural landscape, it was built as a farm silo in 1817, and also served as a tobacco warehouse and box factory before Edna St. Vincent Millay and other members of the Provincetown Players converted the structure into a theatre they christened the Cherry Lane Playhouse, which opened on March 24, 1924, with the play The Man Who Ate the Popomack. During the 1940s The Living Theatre, Theatre of the Absurd, and the Downtown Theater movement all took root there, and it developed a reputation as a showcase for aspiring playwrights and emerging voices.

In one of the many Manhattan properties that Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and her husband owned, Gertrude Whitney established the Whitney Studio Club at 8 West 8th Street in 1914, as a facility where young artists could exhibit their works. By the 1930s it had evolved into her greatest legacy, the Whitney Museum of American Art, on the site of today's New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture. The Whitney was founded in 1931, as an answer to the Museum of Modern Art, founded 1928, and its collection of mostly European modernism and its neglect of American Art. Gertrude Whitney decided to put the time and money into the museum after the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art turned down her offer to contribute her twenty-five-year collection of modern art works.[53] In 1936, the renowned Abstract Expressionist artist and teacher Hans Hofmann moved his art school from East 57th Street to 52 West 9th Street. In 1938, Hofmann moved again to a more permanent home at 52 West 8th Street. The school remained active until 1958, when Hofmann retired from teaching.[54]

On January 8, 1947, stevedore Andy Hintz was fatally shot by hitmen John M. Dunn, Andrew Sheridan, and Danny Gentile in front of his apartment. Before he died on January 29, he told his wife that "Johnny Dunn shot me."[55] The three gunmen were immediately arrested. Sheridan and Dunn were executed.[56]

The Village hosted the nation's first racially integrated nightclub,[57] when Café Society was opened in 1938 at 1 Sheridan Square[58] by Barney Josephson. Café Society showcased African American talent and was intended to be an American version of the political cabarets that Josephson had seen in Europe before World War I. Notable performers there included: Pearl Bailey, Count Basie, Nat King Cole, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald, Coleman Hawkins, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Burl Ives, Lead Belly, Anita O'Day, Charlie Parker, Les Paul and Mary Ford, Paul Robeson, Kay Starr, Art Tatum, Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washington, Josh White, Teddy Wilson, Lester Young, and the Weavers, who also in Christmas 1949, played at the Village Vanguard.

The annual Greenwich Village Halloween Parade, initiated in 1974 by Greenwich Village puppeteer and mask maker Ralph Lee, is the world's largest Halloween parade and America's only major Halloween nighttime parade, attracting more than 60,000 costumed participants, two million in-person spectators, and a worldwide television audience of over 100 million.[59] The parade has its roots in New York's queer community.[52]

Postwar[edit]

Greenwich Village again became important to the bohemian scene during the 1950s, when the Beat Generation focused its energies there. Fleeing from what they saw as oppressive social conformity, a loose collection of writers, poets, artists, and students (later known as the Beats) and the Beatniks, moved to Greenwich Village, and to North Beach in San Francisco, in many ways creating the U.S. East Coast and West Coast predecessors, respectively, to the East Village-Haight Ashbury hippie scene of the next decade. The Village (and surrounding New York City) would later play central roles in the writings of, among others, Maya Angelou, James Baldwin, William S. Burroughs, Truman Capote, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Rod McKuen, Marianne Moore, and Dylan Thomas, who collapsed at the Chelsea Hotel, and died at St. Vincents Hospital at 170 West 12th Street, in the Village after drinking at the White Horse Tavern on November 5, 1953.

Off-Off-Broadway began in Greenwich Village in 1958 as a reaction to Off Broadway, and a "complete rejection of commercial theatre".[60] Among the first venues for what would soon be called "Off-Off-Broadway" (a term supposedly coined by critic Jerry Tallmer of the Village Voice) were coffeehouses in Greenwich Village, in particular, the Caffe Cino at 31 Cornelia Street, operated by the eccentric Joe Cino, who early on took a liking to actors and playwrights and agreed to let them stage plays there without bothering to read the plays first, or to even find out much about the content. Also integral to the rise of Off-Off-Broadway were Ellen Stewart at La MaMa, originally located at 321 E. 9th Street, and Al Carmines at the Judson Poets' Theater, located at Judson Memorial Church on the south side of Washington Square Park.

The Village had a cutting-edge cabaret and music scene. The Village Gate, the Village Vanguard, and the Blue Note (since 1981) regularly hosted some of the biggest names in jazz. Greenwich Village also played a major role in the development of the folk music scene of the 1960s. Music clubs included Gerde's Folk City, The Bitter End, Cafe Au Go Go, Cafe Wha?, The Gaslight Cafe and The Bottom Line. Three of the four members of the Mamas & the Papas met there. Guitarist and folk singer Dave Van Ronk lived there for many years. Village resident and cultural icon Bob Dylan by the mid-60s had become one of the world's foremost popular songwriters, and often developments in Greenwich Village would influence the simultaneously occurring folk rock movement in San Francisco and elsewhere, and vice versa. Dozens of other cultural and popular icons got their start in the Village's nightclub, theater, and coffeehouse scene during the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s. Many artists garnered critical acclaim, some before and some after, performed in the Village. This list includes Eric Andersen, Joan Baez, Jackson Browne, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, Richie Havens, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Ian, the Kingston Trio, the Lovin' Spoonful, Bette Midler, Liza Minnelli, Joni Mitchell, Maria Muldaur, Laura Nyro, Phil Ochs, Tom Paxton, Peter, Paul, and Mary, Carly Simon, Simon & Garfunkel, Nina Simone, Barbra Streisand, James Taylor, and the Velvet Underground. The Greenwich Village of the 1950s and 1960s was at the center of Jane Jacobs's book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which defended it and similar communities, while criticizing common urban renewal policies of the time.

Founded by New York-based artist Mercedes Matter and her students, the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture is an art school formed in the mid-1960s in the Village. Officially opened September 23, 1964, the school is still active, at 8 W. 8th Street, the site of the original Whitney Museum of American Art.[61]

Greenwich Village was home to a safe house used by the radical anti-war movement known as the Weather Underground. On March 6, 1970, their safehouse was destroyed when an explosive device they were constructing was accidentally detonated, killing three of their members (Ted Gold, Terry Robbins, and Diana Oughton).[62]

The Village has been a center for movements that challenged the wider American culture, most notably its seminal role in sparking the gay liberation movement. The Stonewall riots were a series of spontaneous, violent protests by members of the gay community against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn, 53 Christopher Street. Considered together, the demonstrations are widely considered to constitute the single most important event leading to the gay liberation movement and the modern fight for LGBT rights in the United States.[63][64] On June 23, 2015, the Stonewall Inn was the first landmark in New York City to be recognized by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission on the basis of its status in LGBT history,[65] and on June 24, 2016, the Stonewall National Monument was named the first U.S. National Monument dedicated to the LGBTQ-rights movement.[66] Greenwich Village contains the world's oldest gay and lesbian bookstore, Oscar Wilde Bookshop, founded in 1967, while The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center – best known as simply "The Center" – has occupied the former Food & Maritime Trades High School at 208 West 13th Street since 1984. In 2006, the Village was the scene of an assault involving seven lesbians and a straight man that sparked appreciable media attention, with strong statements defending both sides of the case. On June 20, 2023, the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Washington Square North was officially renamed Edie Windsor and Thea Speyer Way at the state level by New York Governor Kathy Hochul, in honor of the Greenwich Village plaintiffs who prevailed at the United States Supreme Court in 2013, in finding the Defense of Marriage Act, which had limited the definition of marriage as being valid strictly between one man and one woman, to be unconstitutional.[67]

Preservation[edit]

Since the end of the 20th century, many artists and local historians have mourned the fact that the bohemian days of Greenwich Village are long gone, because of the extraordinarily high housing costs in the neighborhood.[68] The artists fled to other New York City neighborhoods including SoHo, Tribeca, Dumbo, Williamsburg, and Long Island City. Nevertheless, residents of Greenwich Village still possess a strong community identity and are proud of their neighborhood's unique history and fame, and its well-known liberal live-and-let-live attitudes.[68]

Historically, local residents and preservation groups have been concerned about development in the Village and have fought to preserve its architectural and historic integrity. In the 1960s, Margot Gayle led a group of citizens to preserve the Jefferson Market Courthouse (later reused as Jefferson Market Library),[69] while other citizen groups fought to keep traffic out of Washington Square Park,[70] and Jane Jacobs, using the Village as an example of a vibrant urban community, advocated to keep it that way.

Since then, preservation has been a part of the Village ethos. Shortly after the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) was established in 1965, it acted to protect parts of Greenwich Village, designating the small Charlton-King-Vandam Historic District in 1966, which contains the city's largest concentration of row houses in the Federal style, as well as a significant concentration of Greek Revival houses, and the even smaller MacDougal-Sullivan Gardens Historic District in 1967, a group of 22 houses sharing a common back garden, built in the Greek Revival style and later renovated with Colonial Revival façades. In 1969, the LPC designated the Greenwich Village Historic District – which remained the city's largest for four decades – despite preservationists' advocacy for the entire neighborhood to be designated an historic district. Advocates continued to pursue their goal of additional designation, spurred in particular by the increased pace of development in the 1990s.

Rezoned areas[edit]

The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation (GVSHP), a nonprofit organization dedicated to the architectural and cultural character and heritage of the neighborhood, successfully proposed new districts and individual landmarks to the LPC. Those include:[71]

- Gansevoort Market Historic District was the first new historic district in Greenwich Village in 34 years. The 112 buildings on 11 blocks protect the city's distinctive Meatpacking District with its cobblestone streets, warehouses and rowhouses. About 70 percent of the area proposed by GVSHP in 2000 was designated a historic district by the LPC in 2003, while the entire area was listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places in 2007.[72][73]

- Weehawken Street Historic District, designated in 2006, is a 14-building, three-block district near the Hudson River centering on tiny Weehawken Street and containing an array of architecture including a sailors' hotel, former stables, and a wooden house.[74]

- Greenwich Village Historic District Extension I, designated in 2006, brought 46 more buildings on three blocks into the district, thus protecting warehouses, a former public school and police station, and early 19th century rowhouses. Both the Weehawken Street Historic District and the Greenwich Village Historic District Extension I were designated by the LPC in response to the larger proposal for a Far West Village Historic District submitted by GVSHP in 2004.[74]

- Greenwich Village Historic District Extension II, designated in 2010, embracing 225 buildings on 12 blocks, contains 19th century houses, 19th and 20th century tenements, and a variety of cultural landmarks.[75]

- South Village Historic District, designated in 2013, covers 235 buildings on 13 blocks, representing the largest single expansion of landmark protections in Greenwich Village since 1969. It includes well-preserved and renovated 19th century houses, colorful tenements, and a variety of sites important to the area's rich immigrant, artistic, and Italian-American history, as well as several low-rise, historically significant New York University buildings on Washington Square South.[76]

The Landmarks Preservation Commission designated as landmarks several individual sites proposed by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, including the former Bell Telephone Labs Complex (1861–1933), now Westbeth Artists' Housing, designated in 2011;[77] the Silver Towers/University Village Complex (1967), designed by I.M. Pei and including the Picasso sculpture Portrait of Sylvette, designated in 2008;[78] and three early 19th-century federal houses at 127, 129 and 131 MacDougal Street.

Several contextual rezonings were enacted in Greenwich Village in recent years to limit the size and height of allowable new development in the neighborhood, and to encourage the preservation of existing buildings. The following were proposed by the GVSHP and passed by the City Planning Commission:

- Far West Village Rezoning, approved in 2005, was the first downzoning in Manhattan in many years, putting in place new height caps, thus ending construction of high-rise waterfront towers in much of the Village and encouraging the reuse of existing buildings.[79]

- Washington and Greenwich Street Rezoning, approved in 2010, was passed in near-record time to protect six blocks from out-of-scale hotel development and maintain the low-rise character.[80]

NYU dispute[edit]

New York University and Greenwich Village preservationists have frequently become embroiled in conflicts between the university's campus expansion efforts and the preservation of the scale and character of the Village.[81]

As one press critic put it in 2013, "For decades, New York University has waged architectural war on Greenwich Village."[82] In recent years, the university has clashed most prominently with community groups such as the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation over the construction of new NYU academic buildings and residence halls. During the design of Furman Hall in 2000, the site of which is adjacent to the Judson Memorial Church, community groups sued the university, claiming the construction of a 13-story tower on the site would "loom behind the campanile of [the church]" and "mar the historic silhouette of Greenwich Village as viewed from Washington Square Park". Despite a justice in State Supreme Court dismissing the case, the university agreed to a settlement with the groups to avoid future appeals, which included reducing the building to 9 stories and restoring the facades of two historic houses located on the site, the Judson House and a red-brick town house where Edgar Allan Poe once lived, which NYU reconstructed as they appeared in the 19th century.[83]

Another dispute arose during the construction of the 26-story Founders Hall, a residence hall planned to be constructed on the site of St. Ann's Church at 120 East Twelfth Street. Amidst protests of the demolition of the church, the university decided to maintain and restore the facade and steeple of the building, parts of which were deteriorating or missing, and it now stands freely directly in front of the 12th Street entrance of the building. Further controversy also arose over the height of the building, as well as how the university would integrate the church's facade into the building's uses; however, in 2006, NYU began construction and the new dorm was completed in December 2008.[84][85]

In recent years, the most conflict has arisen over the proposed NYU 2031 plan, which the university released in 2010 as its plan for long-term growth, both within and outside of Greenwich Village. This included a court battle over the City of New York's right to transfer three plots of Department of Transportation-owned land to the university for constructing staging, which plaintiffs claimed required the consent of the state legislature. Ultimately, the Appellate Division of New York's Supreme Court ruled in the university's favor after a lower court blocked the expansion plan; however, so far, the university has only begun construction on 181 Mercer Street, the first building in the planned 1.5-million-square-foot (140,000 m2) expansion southwards.[86][87]

Demographics[edit]

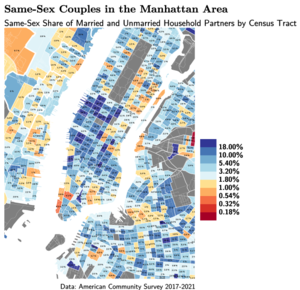

For census purposes, the New York City government classifies Greenwich Village as part of the West Village neighborhood tabulation area.[88] According to the 2010 United States Census, the population of West Village was 66,880, a change of −1,603 (−2.4%) from the 68,483 counted in 2000. Covering an area of 583.47 acres (236.12 ha), the neighborhood had a population density of 114.6/acre (73,300/sq mi; 28,300/km2).[89] The racial makeup of the neighborhood was 80.9% (54,100) White, 2% (1,353) African American, 0.1% (50) Native American, 8.2% (5,453) Asian, 0% (20) Pacific Islander, 0.4% (236) from other races, and 2.4% (1,614) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race were 6.1% (4,054) of the population.[90] Greenwich Village is home to a significant concentration of same-sex couples.

The entirety of Community District 2, which comprises Greenwich Village and SoHo, had 91,638 inhabitants as of NYC Health's 2018 Community Health Profile, with an average life expectancy of 85.8 years.[91]: 2, 20 This is higher than the median life expectancy of 81.2 for all New York City neighborhoods.[92]: 53 (PDF p. 84) Most inhabitants are adults: a plurality (42%) are between the ages of 25–44, while 24% are between 45 and 64, and 15% are 65 or older. The ratio of youth and college-aged residents was lower, at 9% and 10%, respectively.[91]: 2

As of 2017, the median household income in Community Districts 1 and 2 (including the Financial District and Tribeca) was $144,878,[93] though the median income in Greenwich Village individually was $119,728.[2] In 2018, an estimated 9% of Greenwich Village and SoHo residents lived in poverty, compared to 14% in all of Manhattan and 20% in all of New York City. Rent burden, or the percentage of residents who have difficulty paying their rent, is 38% in Greenwich Village and SoHo, compared to the boroughwide and citywide rates of 45% and 51%, respectively. Based on this calculation, as of 2018[update], Greenwich Village and SoHo are considered high-income relative to the rest of the city and not gentrifying.[91]: 7

Manhattan's 3rd Little Italy[edit]

Throughout the 1930s, many Italian-Americans starting leaving Little Italy and moved on the north side of Houston Street and around Bleecker Street and Carmine Street. Many of them being immigrants from Naples and Sicily. Up until the late 2000s, the village was home to one of the largest Italian speaking communities in the United States.[94]

Points of interest[edit]

Greenwich Village includes several collegiate institutions. Since the 1830s, New York University (NYU) has had a campus there. In 1973 NYU moved from its campus in University Heights in the West Bronx (the current site of Bronx Community College), to Greenwich Village with many buildings around Gould Plaza on West 4th Street. In 1976 Yeshiva University established the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in the northern part of Greenwich Village. In the 1980s Hebrew Union College was built in Greenwich Village. The New School, with its Parsons The New School for Design, a division of The New School, and the School's Graduate School expanded in the 2000s, with the renovated, award-winning design of the Sheila C. Johnson Design Center at 66 Fifth Avenue on 13th Street. The Cooper Union is located in Greenwich Village, at Astor Place, near St. Mark's Place on the border of the East Village. Pratt Institute established its latest Manhattan campus in an adaptively reused Brunner & Tryon-designed loft building on 14th Street, east of Seventh Avenue. The university campus building expansion was followed by a gentrification process in the 1980s. There are numerous historic buildings in the neighborhood including Emma Lazarus's former residence on West 10th Street[95] and Edward Hopper's former studio (now the NYU Silver School of Social Work).[96]

The historic Washington Square Park is the center and heart of the neighborhood. Additionally, the Village has several other, smaller parks: Christopher, Father Fagan, Little Red Square, Minetta Triangle, Petrosino Square, and Time Landscape. There are also city playgrounds, including DeSalvio Playground, Minetta, Thompson Street, Bleecker Street, Downing Street, Mercer Street, Cpl. John A. Seravelli, and William Passannante Ballfield. One of the most famous courts, is "The Cage", officially known as the West Fourth Street Courts. Sitting atop the West Fourth Street–Washington Square station at Sixth Avenue, the courts are used by basketball and American handball players from across the city. The Cage has become one of the most important tournament sites for the citywide "Streetball" amateur basketball tournament. Since 1975, New York University's art collection has been housed at the Grey Art Gallery bordering Washington Square Park, at 100 Washington Square East. The Grey Art Gallery is notable for its museum-quality exhibitions of contemporary art.

The Village has a bustling performing arts scene. It is home to many Off Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway theaters; for instance, Blue Man Group has taken up residence in the Astor Place Theater. The Village Gate (until 1992), the Village Vanguard and the Blue Note are still presenting some of the biggest names in jazz on a regular basis. Other music clubs include The Bitter End, and Lion's Den. The Village has its own orchestra aptly named the Greenwich Village Orchestra. Comedy clubs dot the Village as well, including Comedy Cellar, where many American stand-up comedians got their start.

Several publications have offices in the Village, most notably the monthly magazines American Heritage and Fortune and formerly also the citywide newsweekly the Village Voice. The National Audubon Society, having relocated its national headquarters from a mansion in Carnegie Hill to a restored and very green, former industrial building in NoHo, relocated to smaller but even greener LEED certified building at 225 Varick Street,[97] on Houston Street near the Film Forum. The Salvation Army's former American headquarters at 120–130 West 14th Street is in the northern portion of Greenwich Village.[98]

Police and crime[edit]

Greenwich Village is patrolled by the 6th Precinct of the NYPD, located at 233 West 10th Street.[99] The 6th Precinct ranked 68th safest out of 69 patrol areas for per-capita crime in 2010. This is due to a high incidence of property crime.[100] As of 2018[update], with a non-fatal assault rate of 10 per 100,000 people, Greenwich Village's rate of violent crimes per capita is less than that of the city as a whole. The incarceration rate of 100 per 100,000 people is lower than that of the city as a whole.[91]: 8

The 6th Precinct has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 80.6% between 1990 and 2018. The precinct reported 1 murder, 20 rapes, 153 robberies, 121 felony assaults, 163 burglaries, 1,031 grand larcenies, and 28 grand larcenies auto in 2018.[101]

In 1916, Greenwich Village was the site of a lynching, one of the few in New York since the American Civil War. Italian immigrant and working-class shoemaker Paulo Boleta was beaten and trampled to death by a mob after randomly firing his revolver on a crowded street, wounding one bystander.[102]

Fire safety[edit]

Greenwich Village is served by two New York City Fire Department (FDNY) fire stations:[103]

- Engine Company 24/Ladder Company 5/Battalion 2 – 227 6th Avenue[104]

- Squad 18 – 132 West 10th Street[105]

Health[edit]

As of 2018[update], preterm births are more common in Greenwich Village and SoHo than in other places citywide, though births to teenage mothers are less common. In Greenwich Village and SoHo, there were 91 preterm births per 1,000 live births (compared to 87 per 1,000 citywide), and 1 teenage birth per 1,000 live births (compared to 19.3 per 1,000 citywide), though the teenage birth rate is based on a small sample size.[91]: 11 Greenwich Village and SoHo have a low population of residents who are uninsured. In 2018, this population of uninsured residents was estimated to be 4%, less than the citywide rate of 12%, though this was based on a small sample size.[91]: 14

The concentration of fine particulate matter, the deadliest type of air pollutant, in Greenwich Village and SoHo is 0.0095 mg/m3 (9.5×10−9 oz/cu ft), more than the city average.[91]: 9 Sixteen percent of Greenwich Village and SoHo residents are smokers, which is more than the city average of 14% of residents being smokers.[91]: 13 In Greenwich Village and SoHo, 4% of residents are obese, 3% are diabetic, and 15% have high blood pressure, the lowest rates in the city—compared to the citywide averages of 24%, 11%, and 28% respectively.[91]: 16 In addition, 5% of children are obese, the lowest rate in the city, compared to the citywide average of 20%.[91]: 12

Ninety-six percent of residents eat some fruits and vegetables every day, which is more than the city's average of 87%. In 2018, 91% of residents described their health as "good", "very good", or "excellent", more than the city's average of 78%.[91]: 13 For every supermarket in Greenwich Village and SoHo, there are 7 bodegas.[91]: 10

The nearest major hospitals are Beth Israel Medical Center in Stuyvesant Town, as well as the Bellevue Hospital Center and NYU Langone Medical Center in Kips Bay, and NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital in the Civic Center area.[106][107]

Post offices and ZIP Codes[edit]

Greenwich Village is located within four primary ZIP Codes. The subsection of West Village, south of Greenwich Avenue and west of Sixth Avenue, is located in 10014, while the northwestern section of Greenwich Village north of Greenwich Avenue and Washington Square Park and west of Fifth Avenue is in 10011. The northeastern part of the Village, north of Washington Square Park and east of Fifth Avenue, is in 10003. The neighborhood's southern portion, the area south of Washington Square Park and east of Sixth Avenue, is in 10012.[108] The United States Postal Service operates three post offices near Greenwich Village:

- Patchin Station – 70 West 10th Street[109]

- Village Station – 201 Varick Street[110]

- West Village Station – 527 Hudson Street[111]

Education[edit]

Greenwich Village and SoHo generally have a higher rate of college-educated residents than the rest of the city as of 2018[update]. The vast majority of residents age 25 and older (84%) have a college education or higher, while 4% have less than a high school education and 12% are high school graduates or have some college education. By contrast, 64% of Manhattan residents and 43% of city residents have a college education or higher.[91]: 6 The percentage of Greenwich Village and SoHo students excelling in math rose from 61% in 2000 to 80% in 2011, and reading achievement increased from 66% to 68% during the same time period.[112]

Greenwich Village and SoHo's rate of elementary school student absenteeism is lower than the rest of New York City. In Greenwich Village and SoHo, 7% of elementary school students missed twenty or more days per school year, less than the citywide average of 20%.[92]: 24 (PDF p. 55) [91]: 6 Additionally, 91% of high school students in Greenwich Village and SoHo graduate on time, more than the citywide average of 75%.[91]: 6

Schools[edit]

Greenwich Village residents are zoned to two elementary schools: PS 3, Melser Charrette School, and PS 41, Greenwich Village School. Residents are zoned to Baruch Middle School 104. Residents apply to various New York City high schools. The private Greenwich Village High School was formerly located in the area, but later moved to SoHo.[113][114][115]

Greenwich Village is home to New York University, which owns large sections of the area and most of the buildings around Washington Square Park.[6][7] To the north is the campus of The New School, which is housed in several buildings that are considered historical landmarks because of their innovative architecture.[116] The New School's Sheila Johnson Design Center doubles as a public art gallery.[117] Cooper Union has been located in the East Village since its founding in 1859.[118][119]

Libraries[edit]

The New York Public Library (NYPL) operates two branches in Greenwich Village. The Jefferson Market Library is located at 425 Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Avenue). The building was a courthouse in the 19th and 20th centuries before being converted into a library in 1967, and it is now a city-designated landmark.[120] The Hudson Park branch is located at 66 Leroy Street. The branch is housed in Carnegie library that was built in 1906 and expanded in 1920.[121]

Transportation[edit]

Greenwich Village is served by the IND Eighth Avenue Line (A, C, and E trains), the IND Sixth Avenue Line (B, D, F, <F>, and M trains), the BMT Canarsie Line (L train), and the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line (1, 2, and 3 trains) of the New York City Subway. The 14th Street/Sixth Avenue, 14th Street/Eighth Avenue, West Fourth Street–Washington Square, and Christopher Street–Sheridan Square stations are in the neighborhood.[122] Local New York City Bus routes, operated by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, include the M55, M7, M11, M14, and M20.[123] On the PATH, the Christopher Street, Ninth Street, and 14th Street stations are in Greenwich Village.

Notable residents[edit]

Greenwich Village has long been a popular neighborhood for numerous artists and other notable people. Past and present notable residents include:

- Edward Albee (1928–2016), playwright[124]

- Alec Baldwin (born 1958), actor[125][126]

- Richard Barone, musician, producer[127]

- Paul Bateson (born 1940), convicted murderer who was in The Exorcist[128]

- Brie Bella (born 1983), wrestler[129]

- Nate Berkus (born 1971), interior designer[130]

- David Blue (1941–1982), folksinger and companion of Bob Dylan[131]

- Matthew Broderick (born 1962), actor[126][132]

- Barbara Pierce Bush (born 1981), daughter of former U.S. President George W. Bush[133]

- Francesco Carrozzini (born 1982), film director and photographer[134]

- Jessica Chastain (born 1977), actress[126]

- Ramsey Clark (1927–2021), lawyer and activist[135]

- Patricia Clarkson (born 1959), actress[136]

- Francesco Clemente (born 1952) contemporary artist[134]

- Jacob Cohen (1923–1983), statistician and psychologist[137]

- Anderson Cooper (born 1967), CNN anchor[126][138]

- Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), English occultist.[139]

- Hugh Dancy (born 1975), actor[140]

- Claire Danes (born 1979), actress[140]

- Robert De Niro (born 1943), actor[141]

- Brian De Palma (born 1940), film director and screenwriter[126][142]

- Floyd Dell (1887–1969), novelist, playwright, poet and managing editor of The Masses[143]

- Leonardo DiCaprio (born 1974), actor[126]

- Robert Downey Jr. (born 1965), actor and singer[144]

- Steve Earle (born 1955), musician[145]

- Crystal Eastman (1881–1928), lawyer and leader in the fight for woman's suffrage[146]

- Eric Eisner, Hollywood lawyer and former president of The Geffen Film Company[147]

- Maurice Evans (1901–1989), British actor noted for his interpretations of Shakespearean characters[124]

- Andrew Garfield (born 1983), actor[148]

- Hank Greenberg (1911–1986), Hall of Fame baseball player[149]

- John P. Hammond (born 1942), blues singer and guitarist[134]

- Jerry Herman (1931–2019), composer and lyricist[150]

- Dustin Hoffman (born 1937), actor[151]

- Edward Hopper (1882–1967), painter[152]

- Marc Jacobs (born 1963), fashion designer[153]

- Richard Johnson, gossip columnist known for the Page Six column in the New York Post, which he edited for 25 years.[154]

- Wes Joice (1931-1997), owner of the literary hangout, The Lion's Head

- Max Kellerman (born 1973), sports commentator[155]

- Eva Kotchever (1891–1943), owner of Eve's Hangout, also called Eve Adams' Tearoom, situated at 129 MacDougal St, deported to Europe and murdered at Auschwitz.[156]

- Annie Leibovitz (born 1949), photographer[126]

- Arthur MacArthur IV (born 1938), musician, son of General Douglas MacArthur

- Andrew McCarthy (born 1962), actor, writer and television director

- Bob Melvin (born 1961), Major League Baseball player and manager[157]

- Edna St. Vincent Millay, poet and playwright[158]

- Matthew Modine (born 1959), actor and activist

- Julianne Moore (born 1960), actress[159]

- Nickolas Muray (born Miklós Mandl; 1892–1965), Hungarian-born American photographer and Olympic fencer[160]

- Bebe Neuwirth (born 1958), actress[161]

- Edward Norton (born 1969), actor and filmmaker[162]

- Rosie O'Donnell, actress and comedian[126]

- Mary-Kate Olsen, actress and fashion designer[126]

- Mary-Louise Parker, actress[126]

- Sarah Jessica Parker (born 1965), actress[126]

- Sean Parker (born 1979), entrepreneur[126]

- Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849), poet and novelist[163]

- Leontyne Price (born 1927), soprano[164]

- Daniel Radcliffe (born 1989), actor[165]

- Gilda Radner (1946–1989), actress and comedian[126]

- Rachael Ray, television personality and cook[126]

- Julia Roberts (born 1967), actress[126]

- Susan Sarandon (born 1946), actress[126]

- John Sebastian (born 1944), musician[166]

- Amy Sedaris (born 1961), actress[167]

- Adrienne Shelly (1966–2006), actress, film director and screenwriter.[168]

- James Spader, actor[169]

- Anita Steckel (1930–2012), feminist artist known for paintings and photomontages with sexual imagery[170]

- Pat Steir (born 1938), painter and printmaker[134]

- Emma Stone (born 1988), actress[171]

- Uma Thurman (born 1970), actress[172]

- Tiny Tim (1932–1996), singer[citation needed]

- Marisa Tomei (born 1964), actress[173]

- Calvin Trillin (born 1935), feature writer for The New Yorker magazine.[174]

- Liv Tyler (born 1977), actress[175]

- Edgard Varèse (1883–1965), French-born composer[134]

- Chloe Webb (born 1956), actress.[176][177]

- Anna Wintour (born 1949), editor-in-chief of Vogue magazine[134]

In popular culture[edit]

Comics[edit]

- In the DC Comics universe, Wonder Woman lived in the "Village" in New York City (never called by its full name, but clearly depicted as Greenwich Village) during the late 1960s and early 1970s, when she had lost most of her superpowers. Madame Xanadu lived on Chrystie Street, described alternately as being in "Greenwich Village" and the "East Village".[178]

- In the Marvel Comics universe, Master of the Mystic Arts and Sorcerer Supreme, Doctor Strange, lives in a brownstone mansion in Greenwich Village. Doctor Strange's Sanctum Sanctorum is located at 177A Bleecker Street.[179]

- The first generation of Marvel's X-Men frequently visited the Village while not studying at Xavier's School for Gifted Youngsters.[citation needed]

- In Akimi Yoshida's Banana Fish sequel/side story, Garden of Light, Eiji Okumura is stated to live in Greenwich Village as an accomplished photographer.[citation needed]

Film[edit]

- In Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window (1954) James Stewart's character lives in a Greenwich Village apartment.[180]

- In Wonderful Town (1953), the Sherwood sisters leave 1935 Columbus, Ohio, for Greenwich Village to pursue their dreams of becoming a writer (Ruth) and an actress (Eileen). Their apartment was said to be on Christopher Street, though the actual apartment of author Ruth McKenney and her sister Eileen McKenney was at 14 Gay Street.

- In Funny Face (1957), Jo Stockton (Audrey Hepburn) works at a bookstore called Embryo Concepts in the Village, where she is discovered by Dick Avery (Fred Astaire).[181]

- In When Harry Met Sally... (1989), Sally drops Harry off in front of the Washington Square Arch after they share a drive from University of Chicago.[182]

- In Wait Until Dark (1967), Susy Hendrix (Audrey Hepburn) lives at 4 St. Luke's Place.[183]

- Next Stop, Greenwich Village (1976) chronicles the story of a young Jewish boy in 1953 who moves to the Village, looking to break into acting.

- The Pope of Greenwich Village (1984) centers on a maître d' (Mickey Rourke) in the Italian section of the Village.

- Big Daddy (1999), Adam Sandler and Cole/Dylan Sprouse's characters live in a Greenwich Village loft.[184]

- Chinese Coffee (2000), an independent film by Al Pacino, which features Pacino and Jerry Orbach, is set in Greenwich Village in 1982.

- The Collector of Bedford Street (2002) is a documentary about a neighborhood block association on Bedford Street that establishes a trust fund for a mentally disabled man named Larry Selman.[185]

- In I Am Legend (2007), Robert Neville (Will Smith) lives in Washington Square.

- Greenwich Village is the setting for the restaurant 22 Bleecker in the Catherine Zeta-Jones, Aaron Eckhart and Abigail Breslin movie No Reservations (2007).

- In Wanderlust (2012) the characters played by Paul Rudd and Jennifer Aniston live in a New York City apartment located in the West Village.

- In Kids, the characters Telly and Casper head to Washington Square Park to hang out with their skateboarding friends and buy/smoke marijuana.

- The Coen brothers' Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) depicts the Village in the early 1960s, focusing on the emerging folk scene.[186]

- In the Marvel Cinematic Universe live—action film, Avengers: Infinity War (2018), a battle between Tony Stark, Peter Parker, Doctor Strange, Wong, and the Black Order takes place in the Village.

Games[edit]

- Alex's stage in Street Fighter III: 2nd Impact takes place in Greenwich Village.

- Greenwich Village is a playable multiplayer map in the Freedom Fighters (2003) video game.

Literature[edit]

- In her non-fiction, Jane Jacobs frequently cites Greenwich Village as an example of a vibrant urban community, most notably in her 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities.[187]

- Frank and April Wheeler of the 1961 novel Revolutionary Road, and the 2008 film of the same name, used to share an apartment on Bethune Street in the West Village prior to the events of the story.[188]

- O. Henry's 1907 short story, "The Last Leaf", is set in Greenwich Village.

- The anti-hero of the 1961 book Mother Night by author Kurt Vonnegut, and the 1996 film of the same name, Howard W. Campbell Jr., resides in Greenwich Village after World War II and prior to his arrest by the Israelis.[189]

- In Lesley M. M. Blume's children's novel, Cornelia and the Audacious Escapades of the Somerset Sisters, the main characters reside in Greenwich Village.[190]

- The suggestion of moving to the Village shocks newlywed New York aristocrat Jamie "Rick" Ricklehouse in Nora Johnson's 1985 novel Tender Offer. The implication is telling of the Village's reputation in the New York of the 1960s before mass gentrification when it was perceived as lowly and beneath upper class society.[191]

- In Philip Roth's 2000 novel The Human Stain the main character Coleman Silk lives in the Village while studying at NYU.[192]

Music[edit]

- "Sapokanikan" by Joanna Newsom is written about historical events that include the history of Greenwich Village.

- "Cornelia Street" by Taylor Swift is written about the singer's time when she rented an apartment there.[193]

- The cover photo for The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan (1963) of Dylan and his then-girlfriend Suze Rotolo was taken on Jones Street near West 4th Street in Greenwich Village, near their apartment.[194]

- In an interview with Jann Wenner, John Lennon said, "I should have been born in New York, I should have been born in the Village, that's where I belong."[195]

- Buddy Holly and his wife Maria Elena Santiago lived in Apartment 4H of the Brevoort Apartments, at 11 Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village. Here he recorded the series of acoustic songs, including "Crying, Waiting, Hoping" and "What to Do", known as the "Apartment Tapes", which were released after his death.[196]

Television[edit]

- The ABC sitcom Barney Miller (1975–82) was set at the fictional 12th precinct NYPD station in Greenwich Village.[197]

- The CBS sitcom Kate & Allie (1984–1989) was set in Greenwich Village.[198]

- The NBC sitcom Friends (1994–2004) is set in the Village. Central Perk was supposedly on Mercer or Houston Street, down the block from the Angelika Film Center;[d] and Phoebe lived at 5 Morton Street.[e] The building in the exterior shot of Chandler, Joey, Rachel, and Monica's apartment building is at the corner of Grove and Bedford Streets in the West Village.[199] One of the show's working titles was Once Upon a Time in the West Village. However, the address on Rachel's wedding invitation is 495 Grove Street, which is actually in Brooklyn.

- The Village features prominently throughout the six seasons of Mad Men. In Season 1, Don Draper is having an affair with artist Midge Daniels, who lives in the Village. In Season 4, Don moves to an apartment on Waverly Place and Sixth Avenue (specified, for example, in "Public Relations"). And in Season 6, Betty Francis goes to Greenwich Village looking for a family friend, in "The Doorway", and Joan Harris and her girlfriend Kate go on a night on the town that culminates at the Electric Circus, in "To Have and to Hold".[200][201]

- On Sex and the City (1998–2004), exterior shots of Carrie Bradshaw's apartment building are of 66 Perry Street, even though her address is given as on the Upper East Side.[citation needed]

- The NBC Sitcom The Cosby Show (1984–92) made several references to the Village during its run, and the townhouse used for exterior shots, though purportedly set in Brooklyn for purposes of the show, is actually located at 10 St. Luke's Place.[202]

- Mad About You was set in the Village. The Buchman's apartment building was at 5th Avenue & 12th Street, just a few blocks north of Washington Square Park.

- The Real World: Back to New York, the 2001 season of the MTV reality television series The Real World, was filmed in the Village.[203]

- Village Barn (1948–50), the first country music show on network television (NBC) originated from a nightclub of the same name in the basement of 52 West 8th Street.

- Greenwich Village is the setting for Disney's Wizards of Waverly Place and Girl Meets World.

Theater[edit]

- The play Bell, Book and Candle is partly set in Greenwich Village.

See also[edit]

- Cedar Tavern

- The Church of the Ascension

- Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan below 14th Street

- The Market NYC

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan below 14th Street

- Village Care of New York

- Village People

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ During the period of Dutch control over the area, the Village was called Noortwyck ("Northern District", because of its location north of the original settlement on Manhattan Island). (The colony of New Netherland was captured by English forces in 1664.) Dutch colonist Yellis Mandeville, who moved to the Village in the 1670s, called it Groenwijck after the settlement on Long Island, where he previously lived.[5]

- ^ The eleven freed Blacks were Paul d'Angola, Big Manuel, Little Manuel, Manuel de Gerrit de Rens, Simon Congo, Anthony Portuguese. Gracia, Peter Santome, John Francisco, Little Anthony and John Fort Orange.[29]

- ^ James Boorman Johnston (1822–1887) was a son of the prominent Scottish-born New York merchant John Johnston, in partnership with James Boorman (1783–1866) as Boorman & Johnston, developers of Washington Square North, and a founder of New York University; a group portrait of the Johnston Children 1831, is at the Museum of the City of New York[45]

- ^ The Angelika Film Center was said to be "up the block" from Central Perk in "The One Where Ross Hugs Rachel", the sixth season's second episode, placing the coffee house on Mercer Street or Houston.

- ^ This address was given "The One With Joey's New Brain", episode 7–15.

- ^ Pronounced variously /ˈɡrɛnɪtʃ/ GREN-itch, /ˈɡrɛnɪdʒ/ GREN-ij, /ˈɡrɪnɪtʃ/ GRIN-itch, or /ˈɡrɪnɪdʒ/ GRIN-ij.

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b "NYC Planning | Community Profiles". communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov. New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Greenwich Village neighborhood in New York". Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ "National Register Information System – (#79001604)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "NYPL Map Division, Greenwich Village". Nyplmaps.tumblr.com. January 25, 2014. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ "Greenwich Village". nnp.org. Archived from the original on March 17, 2007. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ a b "Campus Map". New York University. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ a b "New York Campus". New York University. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Greif, Mark. "What Was the Hipster?",New York, October 22, 2010. Accessed April 2, 2023. "Hippie itself was originally an insulting diminutive of hipster, a jab at the sloppy kids who hung around North Beach or Greenwich Village after 1960 and didn't care about jazz or poetry, only drugs and fun."

- ^ Yaeger, Lynn. "Why the Coolest Girls Still Go to New York City's Greenwich Village",Vogue, Spring 2017. Accessed April 2, 2023. "For decades they have come here—by plane and train, Greyhound bus and thumb—bright young things in search of a cooler, more meaningful, more creative life. Call them what you will: hipsters, rebels, rule breakers, iconoclasts—these musicians and poets, peace activists and painters, have for more than a century flown their freak flags in the historic alleyways of Greenwich Village."

- ^ Strenberg, Adam (November 12, 2007). "Embers of Gentrification". New York Magazine. p. 5.

- ^ Erin Carlyle (October 8, 2014). "New York Dominates 2014 List of America's Most Expensive ZIP Codes". Forbes. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ West Village Housing, "trulia.com" Archived May 5, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Accessed January 13, 2016.

- ^ F.Y.I. Archived November 12, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, "When did the East Village become the East Village and stop being part of the Lower East Side?", Jesse McKinley, The New York Times, June 1, 1995. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- ^ McFarland, Gerald W. (2005). Inside Greenwich Village: A New York City Neighborhood, 1898-1918. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-1-55849-502-9.

- ^ "Village History". The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ Gold 1988, p. 6

- ^ Harris, Luther S. (2003). Around Washington Square: An Illustrated History of Greenwich Village. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7341-6.

- ^ "neighbourhood, New York City, New York, United States". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Walsh, Kevin (November 1999). "The Street Necrology of Greenwich Village". Forgotten NY. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ "Landmark Maps: Historic District Maps: Manhattan". Nyc.gov. Archived from the original on September 9, 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- ^ Congressional District 10 Archived March 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ New York City Congressional Districts Archived February 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ Senate District 25 Archived March 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ 2012 Senate District Maps: New York City Archived February 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed November 17, 2018.

- ^ Assembly District 66 Archived January 26, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ 2012 Assembly District Maps: New York City Archived February 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed November 17, 2018.

- ^ Current City Council Districts for New York County Archived December 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, New York City. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ Gold 1988, p. 2

- ^ a b Asbury, Edith Evans (December 7, 1977). "Freed Black Farmers Tilled Manhattan's Soil in the 1600s". The New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ Stokes, I.N. Phelps (1915–1928). The iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498–1909 (v. 6). New York, NY: Robert H. Dodd. p. 159. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ Everyday Nature: Knowledge of the Natural World in Colonial New York. Rutgers University Press. January 23, 2024. ISBN 978-0-8135-4379-6.

- ^ "Mordecai Gomez - The Peopling of New York City". macaulay.cuny.edu. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Gold 1988, p. 3

- ^ a b c Burrows & Wallace 1999, pp. 366–367

- ^ Burrows & Wallace 1999, p. 448

- ^ a b Nevius, Michelle & Nevius, James (2009), Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City, New York: Free Press, ISBN 141658997X, p. 53

- ^ Burrows & Wallace 1999, p. 369

- ^ Burrows & Wallace 1999, pp. 505–506

- ^ Walsh, Kevin (2006). Forgotten New York: The Ultimate Urban Explorer's Guide to All Five Boroughs. p. 155.

- ^ Strausbaugh, John (April 2013). The Village: 400 Years of Beats and Bohemians, Radicals and Rogues, a History of Greenwich Village. New York City, USA: Ecco. p. 13. ISBN 978-0062078193.

- ^ a b Julia Goicichea (August 16, 2017). "Why New York City Is a Major Destination for LGBT Travelers". The Culture Trip. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ a b "Workforce Diversity The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ a b Eli Rosenberg (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ "National LGBTQ Wall Of Honor Unveiled At Historic Stonewall Inn". thetaskforce.org. National LGBTQ Task Force. June 27, 2019. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- ^ "Johnston Children: John Taylor Johnston (1820–1893), James Boorman Johnston (1822–1887), Margaret Taylor Johnston (1825–1875), and Emily Proudfoot Johnston (1827–1831), (painting)". SIRIS.

- ^ "Evoking the World of Winslow Homer". The New York Times. August 17, 1997. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ "History of the Tenth Street Studio". Tfaoi.com. November 16, 1997. Archived from the original on May 12, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ "Hotel Albert history". Thehotelalbert.com. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ Gray, Christopher. "The Albert Hotel Addresses Its Myths" Archived July 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, April 15, 2011. Accessed June 21, 2016.

- ^ "The Daily Plant, The Free And Independent Republic Of Washington Square". Nycgovparks.org. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ "The Arch Conspirators: A Centennial Celebration". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on January 21, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

- ^ a b Bryan van Gorder (October 22, 2018). "THE QUEER HISTORY (AND PRESENT) OF NYC'S VILLAGE HALLOWEEN PARADE". Logo TV. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Berman, Avis (1990). Rebels on Eighth Street: Juliana Force and the Whitney Museum of American Art. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 9780689120862.

- ^ "Hans Hofmann Estate, retrieved December 19, 2008". Hanshofmann.org. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- ^ "National Affairs: A Date at The Dance Hall". Time.com. March 7, 1949. p. 1.

- ^ "National Affairs: A Date at The Dance Hall". Time.com. March 7, 1949. p. 2.

- ^ William Robert Taylor, Inventing Times Square: commerce and culture at the crossroads of the world (1991), p. 176

- ^ Many sources give the address at 2 Sheridan Square: "Barney Josephson, Owner of Cafe Society Jazz Club, Is Dead at 86" Archived November 12, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times; see history of "The theater at One Sheridan Square" Archived October 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Village Halloween Parade. "History of the Parade". Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ Viagas (2004, p. 72)

- ^ Matter, Mercedes (2002). "New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture: The School: Its History". nyss.org. New York Studio School. Archived from the original on April 26, 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ^ Rudd, Mark. "I Was Part of the Weather Underground. Violence Is Not the Answer.", The New York Times, March 5, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2024. "Fifty years ago, on March 6, 1970, an explosion destroyed a townhouse on West 11th Street in New York’s Greenwich Village. Three people — Terry Robbins, 22, Ted Gold, 22, and Diana Oughton, 28, all close friends of mine — were obliterated when bombs they were making exploded prematurely. Two others, Kathy Boudin, 26, and Cathlyn Wilkerson, 25, escaped from the rubble."

- ^ National Park Service (2008). "Workforce Diversity: The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". US Dept. of Interior. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ "Obama inaugural speech references Stonewall gay-rights riots". North Jersey Media Group. January 21, 2013. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ "NYC grants landmark status to gay rights movement building". North Jersey Media Group. Associated Press. June 23, 2015. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ Eli Rosenberg (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ "Video, Audio, Photos & Rush Transcript: Governor Hochul Delivers Remarks at the Edie Windsor and Thea Spyer Way Street Naming". State of New York. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ a b *Roberts, Rex (July 29, 2002). "When Greenwich Village was a Bohemian paradise". Insight on the News. Archived from the original on December 25, 2007. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- Harris, Paul (August 14, 2005). "New York's heart loses its beat". Arts. London: Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- Kugelmass, Jack (November 1993). ""The Fun Is in Dressing up": The Greenwich Village Halloween Parade and the Reimagining of Urban Space". Social Text. 36 (36): 138–152. doi:10.2307/466393. JSTOR 466393.

- Lydersen, Kari (March 15, 1999). "SHAME OF THE CITIES: Gentrification in the New Urban America". LiP Magazine. Archived from the original on December 25, 2007. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- Desloovere, Hesper (November 15, 2007). "City Living: Greenwich Village". New York City. Newsday. Archived from the original on December 25, 2007. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- Fieldsteel, Patricia (October 19, 2005). "Remembering a time when the Village was affordable". The Villager. 75 (22). New York: Community Media LLC. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ "Margot Gayle, Urban Preservationist and Crusader With Style, Dies at 100". The New York Times. September 30, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ NYC Dept. of Parks and Recreation. "Shirley Hayes and the Preservation of Washington Square Park".

- ^ The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. "Preservation". Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ The New York Times (September 11, 2003). "Blood on the Street, and it's Chic". The New York Times. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ The Villager. "Gansevoort Historic District Gets Final Approval From City". Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ a b The Observer. "Village Historic District Extension". Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "Panel Enlarges Landmark Zone and Cites 2 Bronx Sites". The New York Times. June 22, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ The Villager. "Positively South Village: LPC Votes to Expand Historic District". Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ The Villager. "City Dubs Westbeth a Landmark". Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "Pei's University Village Tops List of 7 Landmarks". The New York Times. November 18, 2008. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "City, Landmarks Looking to Rezone Part of West Village". Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "Council Approves 2 Village Rezonings". crainsnewyork.com. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Eli Rosenberg (March 19, 2014). "After A Long War, Can NYU and the Village Ever Make Peace?". Vox Media Inc. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ Russell, James (December 11, 2013). "NYU Blights Village With Dumpsters, Fencing, Concrete". Bloomberg. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ O'Grady, Jim (January 23, 2001). "N.Y.U. Law School Agrees To Save Part of Poe House". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Lincoln (August 2, 2006). "Conceding nothing, NYU starts building megadorm". The Villager. Vol. 76, no. 11. Archived from the original on August 20, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ "Ettinger Engineering Associates | Portfolio | New York University Founders Hall". www.ettingerengineering.com. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Holmes, Helen B. (November 16, 2016). "Supreme Court Clears The Way For NYU 2031 Expansion Plan". Medium. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Bagli, Charles (January 7, 2014). "Judge Blocks Part of NYU's Plan for Four Towers in Greenwich Village". The New York Times. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010 Archived November 29, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, February 2012. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- ^ Table PL-P5 NTA: Total Population and Persons Per Acre – New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010 Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Population Division – New York City Department of City Planning, February 2012. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- ^ Table PL-P3A NTA: Total Population by Mutually Exclusive Race and Hispanic Origin – New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010 Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Population Division – New York City Department of City Planning, March 29, 2011. Accessed June 14, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Greenwich Village and Soho (Including Greenwich Village, Hudson Square, Little Italy, Noho, Soho, South Village and West Village)" (PDF). nyc.gov. NYC Health. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ a b "2016-2018 Community Health Assessment and Community Health Improvement Plan: Take Care New York 2020" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 9, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ "NYC-Manhattan Community District 1 & 2--Battery Park City, Greenwich Village & Soho PUMA, NY". Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ Berman, Andrew. "Uncovering the sites of the South Village’s secret 'Little Italy'", 6sqft, October 5, 2017. Accessed January 18, 2024. "But some of the most historically significant sites relating to the Italian-American experience in New York can be found in the Greenwich Village blocks known as the South Village–from the first church in America built specifically for an Italian-American congregation to the cafe where cappuccino was first introduced to the country, to the birthplace of Fiorello LaGuardia, NYC’s first Italian-American mayor."

- ^ "Gesso". gesso.fm. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ "Gesso". gesso.fm. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Claire (April 6, 2008). "Audubon's New Home Brings the Outdoors In". The New York Times.

- ^ The Salvation Army National and Territorial Headquarters (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 17, 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "NYPD – 6th Precinct". www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ "Greenwich Village – DNAinfo.com Crime and Safety Report". www.dnainfo.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ "6th Precinct CompStat Report" (PDF). www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 13, 2018. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ Barrow, Janice Hittinger (September 1, 2005). "Lynching in the Mid-Atlantic, 1882–1940". American Nineteenth Century History. 6 (3): 241–271. doi:10.1080/14664650500380969. ISSN 1466-4658.

- ^ "FDNY Firehouse Listing – Location of Firehouses and companies". NYC Open Data; Socrata. New York City Fire Department. September 10, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Engine Company 24/Ladder Company 5/Battalion 2". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Squad 18". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Manhattan Hospital Listings". New York Hospitals. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Best Hospitals in New York, N.Y." U.S. News & World Report. July 26, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Greenwich Village, New York City-Manhattan, New York Zip Code Boundary Map (NY)". United States Zip Code Boundary Map (USA). Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Patchin". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Village". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: West Village". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.