Odia people

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (February 2023) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2017) |

ଓଡ଼ିଆ ଲୋକ (Oṛiā Lōka) | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. 34 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 33,026,680 (2011) | |

| 104,000[2] | |

| 97,000 [3] | |

| 72,000 [4] | |

| 38,000[5] | |

| Languages | |

| Odia | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly: Minorities:

| |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Odisha |

|---|

|

| Governance |

| Topics |

|

Districts Divisions |

| GI Products |

|

|

The Odia (ଓଡ଼ିଆ), formerly spelled Oriya, are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group native to the Indian state of Odisha who speak the Odia language. They constitute a majority in the eastern coastal state, with significant minority populations existing in the neighboring states of Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and West Bengal.[6]

Etymology[edit]

The earliest Odias were called by the names of Odra and Kalinga janapadas (township) of ancient Odisha, which later became Utkal. The word Odia is mentioned in epics like the Mahabharata. The Odras are mentioned as one of the peoples that fought in the Mahabharata. Pali literature calls them Oddakas. Ptolemy and Pliny the Elder also refer to the Oretas who inhabit India's eastern coast. The modern term Odia dates from the 15th century when it was used by the medieval Muslim chroniclers and adopted by the Gajapati kings of Odisha.

History[edit]

Ancient period[edit]

The Odias are distinguished by their ethnocultural customs as well as the use of the Odia language. Odisha's relative isolation and the lack of any discernible outside influence has contributed towards the preservation of a social and religious structure that has disappeared from most of north and southern part of India.[citation needed]

The inhabitants of Odisha were known as Odras, Utkal and Kalinga in the Mahabharata. During the 3rd century BCE, coastal Odisha was known as Kalinga. According to the Mahabharata, the Kalinga extended from the mouth of the Ganga in the north to the mouth of the Godavari in the south.

During the 4th century, Mahapadma Nanda conquered Kalinga. During the rule of Ashoka, Kalinga was annexed as part of Maurya Empire. During the 2nd century BCE, Kharavela emerged as a powerful ruler. He defeated several kings in north and south India. During this period, Utkala was the centre of Buddhism and Jainism.

During the reign of the Gupta Empire, Samudra Gupta conquered Odisha.

Medieval period[edit]

The Shailodbhava dynasty ruled the region from the 6th to the 8th century. They built the Parashurameshvara Temple in the 7th century, which is the oldest known temple in Bhubaneswar. The Bhauma-Kara dynasty ruled Odisha from the 8th to the 10th century. They built several Buddhist monasteries and temples, including that of Lalitgiri, Udayagiri and Baitala Deula. The Keshari dynasty ruled from the 9th to the 12th century. They constructed the Lingaraj Temple, Mukteshvara Temple and Rajarani Temple in Bhubaneswar.[7] They introduced a new style of architecture in Odisha, and their rule saw a shift from Buddhism to Brahmanism.[8] The Eastern Ganga dynasty then ruled Odisha from the 11th to the 15th century. They constructed the Konark temple. The Gajapati Empire ruled the region in the 15th century. The empire extended from the Ganga River in the north to the Kaveri River in the south during the reign of Kapilendra Deva.

Modern period[edit]

Odisha remained an independent regional power until the early 16th century A.D. It was conquered by the Mughals under Akbar in 1568 and was thereafter subject to a succession of Mughal and Maratha rule before coming under British control in 1803.[9]

In 1817, a combination of high taxes, administrative malpractice by the zamindars and dissatisfaction with the new land laws led to a revolt against Company rule breaking out, which many Odias participated in. The rebels were led by general Jagabandhu Bidyadhara Mohapatra Bhramarbara Raya.[10][11] Another series of rebellions and uprisings led by numerous Odias, such as the Tapang rebellion (1827), Banapur rebellion (1835), Sambalpur uprising (1827–62), Ghumsur Kondh uprising (1835), Kondh rebellion (1846–55), Bhuyan uprising (1864), and Ranapur Praja Revolt (1937–38), made it difficult for the British to maintain absolute authority over Odisha.[citation needed]

During the period of Maratha control, major Odia regions were transferred to the rulers of Bengal that resulted in successive decline of the language over the course of time in vast regions that stretched until today's Midnapore district of West Bengal.[12][better source needed] The British colonial administration subsequently transferred Odia areas to the neighbouring non-Odia administrative divisions that also contributed to the decline of the Odia language in the formerly core regions of Odisha, or Kalinga, due to linguistic and cultural assimilation. Following popular movements and the rise of consciousness of Odia identity, a major part of the new Odisha state was first carved out from the Bengal Presidency in 1912.

Finally, Odisha became a separate province and the first officially recognized language-based state of India in 1936 after the amalgamation of the Odia regions from Bihar and Orissa Province, Madras Presidency and Chhattisgarh Division was successfully executed. Twenty-six Odia princely states, including Sadheikala-Kharasuan in today's Jharkhand, also signed a merger with the newly formed Odisha state, while many major Odia-speaking areas were left out due to political incompetence.[13]

Geographic distribution[edit]

Although the total Odia population is unclear, the 2001 census of India puts the population of Odisha at around 36 million. There are smaller Odia communities in the neighbouring states of West Bengal, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh. Most Odias in West Bengal live in the districts of Midnapore and Bankura. Surat in Gujarat also has a large Odia population, primarily diamond workers in the southern district of Ganjam. Bengaluru and Hyderabad have sizable Odia population due to an IT boom in the late 2000s. Some Odias have migrated to Bangladesh, where they are known as the Bonaz community.

While the southern part of the state has intermigration within India, the northern part has migration towards the Middle East and the Western world. Balasore and Cuttack are known as the immigration centres of Odisha.

Diaspora[edit]

The Odia population abroad originates predominantly from the northern district of Balasore, followed by Cuttack and Bhadrak. The migrants who work within the country predominantly originate from the Ganjam and Puri districts.

Migration to the United Kingdom has been recorded since 1935, where mostly people from Balasore in undivided Bengal province went to work, thereafter continuing a chain migration, very predominant then, which continues to this day. Most British Odias have obtained British citizenship.

In the late 2000s, many Odias, predominantly from Balasore and Cuttack, migrated to Australia. This resulted in chain migration, predominantly from Balasore and Cuttack.

During the 2009, Odias predominantly from Balasore, Bhadrak and Cuttack migrated to Germany in particular for obtaining their educations and turning their degrees as the subject to earn high salaries in the IT sectors in the European Union.

Communities[edit]

The Odia people are subdivided into several communities such as the Brahmin, Jyotish, Karan, Khandayat, Gopal, Kumuti (Kalinga Vaishya),[14] Chasa, Bania, Kansari, Gudia, Patara, Tanti, Teli, Badhei , Kamara, Barika, Mali, Kumbhar, Siyal caste(panjab origin),[15] Sundhi, Keuta, Dhoba, Bauri, Kandara, Domba, Pano, and Hadi.[16]

Language and literature[edit]

Around 35–40 million people in Odisha and adjoining areas speak and use the Odia language, which is also one of the six classical languages of India.[17] Odia words are found in the 2nd century B.C. Jaugada inscriptions of emperor Ashoka and 1st century B.C. Khandagiri inscriptions of emperor Kharavela.[clarification needed] Known as Odra Bibhasa, or as Odra Magadhi Apabrhamsa in ancient times, the language has been inscribed throughout the last two millennia in ancient Pali, Prakrit, Sanskrit and Odia scripts.

The Buddhist Charyapadas were composed from the 7th to the 9th century by Buddhists like Rahula, Saraha, and Luipa.

The literary traditions of Odia achieved prominence towards the rule of the Somavamshi and Eastern dynasty. In the 14th century, during the rule of emperor Kapilendra Deva Routray, the poet Sarala Dasa wrote the Mahabharata, Chandi Purana, and Bilanka Ramayana, praising the goddess Durga. Rama-bibaha, written by Arjuna Dasa, was the first long poem written in Odia. Major contributions to the Odia language in the Middle Ages were contributed by Panchasakha, Jagannatha Dasa, Balarama Dasa, Acyutananda, Yasovanta and Ananta.

Mughalbandi or Kataki Odia, spoken in the Cuttack, Khordha and Puri districts, is generally considered to be the standard dialect and is the language of instruction and media.

There are eight major forms of Odia spoken across Odisha and adjoining areas, while another thirteen minor forms are spoken by tribal and other groups of people.

New literary traditions are emerging in the western Odia form of the language which is Sambalpuri and prominent poets and writers have emerged like Haldar Nag.

Culture[edit]

Art[edit]

Odissi is one of the oldest classical dances of India. The Applique work of Pipili and Sambalpuri sarees are notable. The silver filigree work from Cuttack and Pattachitra of Raghurajpur are some really authentic representation of ancient Indian art and culture.

Odias were the master of swords and had their own form of martial arts, later popularly known as "Paika akhada".

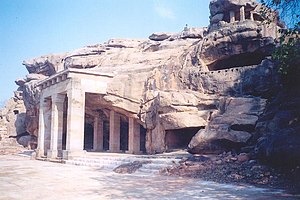

Architecture[edit]

Odia architecture has a regional architectural tradition that dates back to at least the 6th century from the times of the Shailodbhava dynasty. From the times of the Somavamshi and the Eastern Ganga dynasty the Kalinga architecture form achieved prominence with its special style of temple designs which consist of four major sections of a religious structure, namely Mukha Deula, Nata Mandapa, Bhoga Mandapa and Garba Griha (or the inner sanctum). The examples of these marvelous structures are prevalent across the several hundreds of temples build across the state of Odisha mainly in Bhubaneswar which happens to be known as the temple city. Puri Jagannath temple, ruins of the Konark Sun temple, Lingaraj temple, etc. are the living examples of ancient Kalinga architecture.

Cuisine[edit]

Seafood and sweets dominate Odia cuisine. Rice is the staple cereal and is eaten throughout the day. Popular Odia dishes are Rasagolla, Rasabali, Chhena Poda, Chhena kheeri, Chhena jalebi, Chenna Jhilli, Chhenagaja, Khira sagara, Dalma,Tanka torani and Pakhala. Machha Besara (Fish in mustard gravy), Mansha Tarkari (Mutton curry), sea foods like Chingudi Tarakari (Prawn curry), and Kankada Tarakari (Crab curry). A standard Odia meal includes Pakhala (watered rice), Badhi Chura, Saga Bhaja (Spinach fry), Macha Bhaja, Chuin Bhaja, etc.[18][19]

Festivals[edit]

A wide variety of festivals are celebrated throughout the year; There is a saying in Odia, ‘Baarah maase, terah parba’, that there are 13 festivals in 12 months of a year. Well known festivals, that are popular among the Odia people, are the Ratha Yatra, Durga Puja, Kali Puja, Nuakhai, Pushpuni, Pua Jiunita, Raja, Dola Purnima, Astaprahari, Pana Sankranti (as Vaisakhi is called in Odisha ), Kartik Purnima / Boita Bandana, Khudrukuni puja /Tapoi Osa, Kumar Purnima, Ditia Osa, Chaitra Purnima, Agijala Purnima, Bhai Juntia, Pua Jiuntia, Jhia Juntia, Sabitri Brata, Sudasha Brata, Manabasa Gurubara etc.[20]

Religion[edit]

Odisha is one of the most religiously homogeneous states in India. More than 94% of the people are followers of Hinduism.[21] Hinduism in Odisha is more significant due to the specific Jagannath culture followed by Odia Hindus. The practices of the Jagannath sect is popular in the state and the annual Rath Yatra in Puri draws pilgrims from across India.[22] Under the Hindu religion, Odia people are believers of a wide range of sects with roots to historical times.

Before the advent of the Vaisnava sects Purrushotam Jagannath cult in Odisha, Buddhism and Jainism were two very prominent religions. According to Jainkhetra Samasa, the Jain tirthankar Prasvanth came to Kopatak which is now Kupari of Baleswar district and was the guest of a person called Dhanya. The Kshetra Samasa, says that Parsvnath preached at Tamralipti (now Tamluk in Bengal) of Kalinga. The national religion of ancient Odisha became Jainism during the time of the emperor Karakandu in the 7th century B.C. The Kalinga Jina asana was established and the idol of Tirthankara Rishabhanatha then also known as the "Kalinga Jina"was the national symbol of the kingdom. Emperor Mahmeghvahana Kharavela was also a devout Jain and a religiously tolerant ruler who reclaimed and re-established the Kalinga Jina that was taken away as a victory token by the Magadhan king, Mahapadma Nanda.

Buddhism was also a prevalent religion in the Odisha region until the late Bhaumakar dynasty's rule. Remarkable archaeological findings like at Dhauli, Ratnagiri, Lalitgiri, khandagiri and Puspagiri across the state have unearthed the buried truth about the Buddhist past of Odisha in a large scale. Even today we can see the Buddhist impact on the socio-cultural traditions of the Odia people. Though a majority of Buddhist shrines lay undiscovered and buried, the past of Odia people is rich with descriptions about them in the Buddhist literature. The tooth relic of Buddha was first hosted by ancient Odisha as the king Brahmadutta constructed a beautiful shrine in his capital Dantapura (assumed to be Puri) of Kalinga. Successive dynasties in ancient Odisha's Kalinga or Tri Kalinga region were tolerant and secular in their governance over all the existing religions with Vedic roots. This provided a peaceful and secure environment for all the religious ideologies to flourish in the region for over a time period of three thousand years. The founder of Vajrayana Buddhism, King Indrabhuti was born in Odisha along with other prominent monks like Saraha, Luipa, Lakshminara and characters of Buddhist mythology like Tapassu and Bahalika were born in Odisha.

Hindu sects like Shaivism and Shaktism are also the oldest ways of Hindu belief systems in Odisha with many royal dynasties dedicating remarkable temples and making them state religion over their time of rule in history. Lingaraja, Rajarani, Mausi Maa Temple and other Temples in Bhubaneswar are mostly of Shaivaite sect while prominent temples of goddesses like Samleswari, Tara-Tarini, Mangala, Budhi Thakurani, Tarini, Kichekeswari and Manikeswari, across Odisha are dedicated to the Shakti and Tantric cult.

The Odia culture is now mostly echoed through the spread of Vaishnavite Jagannath culture across the world and the deity Jagannath himself is deeply rooted to every household traditions, culture and religious belief of Odia people today. There are historical references of wooden idols of Hindu deities being worshiped as a specific trend of Kalinga region far before the construction of Puri Jagannath temple by the king, Choda Ganga Deva in 12th century.

Lately converted Christians are generally found among the tribal people especially in the interior districts of Gajapati and Kandhamal. Around 2% of the people are Odia Muslims, most of them are indigenous though a small population are migrants from North India and elsewhere. The larger concentration of the minority Muslim population is in the districts of Bhadrak, Kendrapada and Cuttack.

Music and dance[edit]

Odissi music dates back as far as the history of the classical Odissi dance goes back. At present, the Odissi music is being lobbied by the intellectual community of the state to be recognized as a classical form of music by the cultural ministry of India. Be side Classical Odissi dance, there are some other prominent cultural and folk dance forms of the Odia people that have followed different parts if evolution over the ages.

- Odissi: A Major ancient classical dance.

- Mahari: A predecessor of Odissi dance that was mostly performed by the temple Devadashi community or royal court performers.

- Laudi Badi Khela:Is a traditional dance of Odisha. This is performed during Dola Purnima by Gopal (Yadav) community of Odisha.

- Dhemsa: Is a very popular dance format of the tribal area Undivided Koraput districts of Odisha. This generally performed by the Bhartas/Gouda/Parja Community of Koraput & Nabarangapur during the celebration.

- Gotipua

The folk dance forms have evolved over ages with direct tribal influence over them. They are listed as below.

- Chhau: The Odia Chhau dance is a direct result of its ancient martial traditions which are depicted in dance performances. Though Chhau is basically an Odia art form, it is also performed in West Bengal. Saraikella Chhau and Mayurbhanj Chhau are the only two Odia variants that have survived over time with its originality.

- Ghumura dance: Is a direct result of the ancient martial traditions of the Odias when Odia Paikas who marched into the battlefield or rested on the beats and tunes of the Ghumura music.

- Dalkhai Dance: Though this dance form has evolved from tribal dance forms, it shows a complex mix of the themes taken from various religious texts of Hinduism. It is very a popular folk dance form of western Odisha.

- Jodi Sankha: It also derives itself from the martial traditions of ancient Odisha and the performers use only the music generated from the two conchs held by each of them.

- Baagh Nach

Modern Odias have also adopted western dance and forms. Remarkably, the Prince dance group was declared as the winner of TV reality show "India's Got Talent" in the year 2009 and Ananya Sritam Nanda was declared as the winner of junior Indian Idol in the year 2015.

Entertainment[edit]

Ancient traces of entertainment can be traced to the rock edicts of Emperor Kharavela which speaks about the festive gatherings held by him in the third year of his rule that included shows of singing, dancing and instrumental music. Ancient temple art of the Odias give a strong and silent testimony to the evolution of Odissi classical dance form over the ages. Bargarh district's Dhanujatra which is also believed to be world's largest open air theater performance, Pala and Daskathia, Jatra or Odia Opera, etc. are some of the traditional ways of entertainment for masses that survive to this day. Modern Odia television shows and movies are widely appreciated by a large section of the middle class section of the Odias and the it continues to evolve at a rapid rate with innovative ways of presentation.[23]

Notable people[edit]

- Achyutananda – Indian devotional Poet from Odisha

- Binayak Acharya – Indian politician (1918–1983)

- Afzal-ul Amin – Indian politician and social worker (1915-1983)

- Subroto Bagchi – Indian entrepreneur and business leader

- Bhikari Bal – Indian singer (1929–2010)

- Hemananda Biswal – Indian politician (1939–2022)

- Bhagabat Behera – Indian politician from Odisha (1940–2002)

- Chakradhar Behera – Revolutionary from Odisha, India

- Chandi Prasad Mohanty

- Sanatan Mahakud – Indian politician

- Krishna Beura – Indian playback singer

- Kadambini Mohakud – Cricketer

- Dutee Chand – Indian sprinter (1996–)

- Nabakrushna Choudhuri – Indian politician (1901-1984)

- Ashok Das – Indian American physicist

- Bibhusita Das – Indian marine engineer

- Bidhu Bhusan Das – Indian academic (1922-1999)

- Bishwanath Das – Indian politician, lawyer, and philanthropist

- Gopabandhu Das – Indian writer (1877–1928)

- Madhusudan Das – Elderly and prominent freedom fighter, lawyer and social reformer from Odisha

- Manoj Das – Indian author (1934–2021)

- Nandita Das – Indian actress, director

- Prabhat Nalini Das – Indian academic

- Shaktikanta Das – Governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI)

- Anil Dash – American technology executive and entrepreneur

- Rajendra Narayan Singh Deo – Politician from Odisha, India

- Giridhar Gamang – Indian politician

- Hussain Rabi Gandhi – Indian writer and politician (1948–2023)

- Biswabhusan Harichandan – Indian politician (born 1934)

- Mehmood Hussain – Indian filmmaker

- Madhu Sudan Kanungo – gerontologist

- Indrajit Mahanty – Former Chief Justice of Tripura High Court

- Harekrushna Mahatab – Politician from Odisha, India

- Lalit Mansingh – Indian diplomat

- Chaturbhuj Meher – Indian weaver

- Gangadhar Meher – A renowned Odia poet of the 19th century

- Kailash Chandra Meher – Indian artist and painter

- Kunja Bihari Meher – Indian weaver (1928–2008)

- Sadhu Meher – Indian actor, director and producer (1939/1940–2024)

- Atharuddin Mohammed – Dewan of Dhenkanal

- Pramod Kumar Mishra – Indian bureaucrat and principal secretary to the Prime Minister of India

- Sabyasachi Mishra – Indian film actor

- Baidyanath Misra – Indian economist, educationist, author, and administrator

- B. K. Misra – Neurosurgeon

- Dipak Misra – 45th Chief Justice of India

- Ranganath Misra – 21st Chief Justice of India

- Tapan Misra – Indian scientist

- Biren Mitra – Indian politician (1917–1978)

- Sayeed Mohammed – Indian Odia educationist, freedom fighter and philanthropist

- Anubhav Mohanty – Odia actor and politician

- Baisali Mohanty – Odissi dancer

- Debashish Mohanty – Indian cricketer

- Surendra Mohanty – Odia writer, politician

- Uttam Mohanty – Indian actor

- Bibhu Mohapatra – Indian American Fashion designer

- Kelucharan Mohapatra – Indian classical dancer (1926–2004)

- Sona Mohapatra – Indian singer

- Arabinda Muduli – Odia singer, musician, lyricist (1961-2018)

- Srabani Nanda – Indian sprinter

- Bibhuti Bhushan Nayak – Indian journalist (born 1965)

- Pragyan Ojha – Former Indian cricketer

- Nila Madhab Panda – Indian film director

- Arun K. Pati – Indian physicist

- Biju Patnaik – Indian politician, aviator, and businessman

- Janaki Ballabh Patnaik – Politician from Odisha, India (1927–2015)

- Jayanti Patnaik – Indian parliamentarian and social worker (1932–2022)

- Naveen Patnaik – 14th Chief Minister of Odisha

- Sudarshan Patnaik – Indian Sand Artist

- Sambit Patra – Indian politician (born 1974)

- Devdutt Pattanaik – Indian mythologist and writer (born 1970)

- Dharmendra Pradhan – Indian politician

- Manasi Pradhan – Indian writer and Women's rights activist

- S.N. Pradhan – Director general of police

- Ramakanta Rath – Indian poet from Odisha

- Ekram Rasul

- Nilamani Routray – Indian politician (1920–2004)

- Sarojini Sahoo – Indian (Odia) Writer

- Archita Sahu – Indian actress and model

- Jairam Samal – Odia actor

- Debasish Samantray – Indian cricketer

- Biplab Samantray – Indian cricketer

- Pratap Chandra Sarangi – Indian politician

- Nandini Satpathy – Politician from Odisha, India (1931–2006)

- Fakir Mohan Senapati – Indian Odia author

- Sadashiva Tripathy – Chief Minister of Odisha (1910-1980)

- Bijaya Kumar Sahoo – Indian educationalist (1963–2021)

- Ashwini Vaishnaw – Indian politician and civil servant (born 1970)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Odia". ethnologue.

- ^ "Odias in the UK". Times Now. 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Census shows Indian population and languages have exponentially grown in Australia". SBS Australia. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Baumann, Martin. "Immigrant Hinduism in Germany:". Harvard University.

- ^ "New Zealand". Stats New Zealand. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ Minahan, James (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ISBN 9781598846591.

- ^ Smith, Walter (1994). The Mukteśvara Temple in Bhubaneswar. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-208-0793-8.

- ^ Smith 1994, p. 26.

- ^ GYANENENDRA NATH MITRA (25 December 2019). "Book by British ICS officer covers 'Orissa' as a whole". dailypioneer. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ Sayed Jafar Mahmud (1994). Pillars of Modern India 1757-1947. APH Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-7024-586-5. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "'Paika Bidroha' to be named as 1st War of Independence - NATIONAL - The Hindu". The Hindu.

- ^ Sengupta, N. (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-81-8475-530-5.

- ^ Sridhar, M.; Mishra, Sunita (5 August 2016). Language Policy and Education in India: Documents, contexts and debates. ISBN 9781134878246. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ Timon Tim. HISTORICAL GLANCE ON KALINGA VAISHYA COMMUNITY OR 'KUMUTI' CASTE.

- ^ Indian Antiquary: A Journal of Oriental Research in Archaeology, History, Literature, Languages, Folklore Etc. Education Society's Press. 1884.

- ^ Nab Kishore Behura; Ramesh P. Mohanty (2005). Family Welfare in India: A Cross-cultural Study. Discovery Publishing House. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-81-7141-920-3.

- ^ "Odia gets classical language status - NATIONAL - The Hindu". The Hindu.

- ^ "Cuisine Of Odisha". odishanewsinsight. 16 November 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ "Odia delicacies in Bengaluru's first 'Ama Odia Bhoji' to tickle taste buds". aninews. 12 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ "The tenacious people of Odisha". telanganatoday. 2 December 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- ^ "Lord Jagannath's Rathyatra as a Marker of Odia Identity". thenewleam. 23 July 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ "First archives for Odia films soon". The New Indian Express. 25 June 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2022.