Shivaji

| Shivaji I | |

|---|---|

| Shakakarta[1] Haindava Dharmoddharak[2] Shakakarta[1] Haindava Dharmoddharak[2] Mountain Rat[3][4] | |

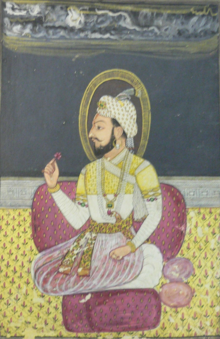

Portrait of Shivaji (c. 1680s), British Museum | |

| 1st Chhatrapati of the Maratha Empire | |

| Reign | 6 June 1674–3 April 1680 |

| Coronation |

|

| Predecessor | Position established |

| Successor | Sambhaji |

| Born | 19 February 1630 Shivneri Fort, Ahmadnagar Sultanate (present-day Maharashtra, India) |

| Died | 3 April 1680 (aged 50) Raigad Fort, Mahad, Maratha Empire (present-day Maharashtra, India) |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | 8,[6] including Sambhaji and Rajaram I |

| House | Bhonsle |

| Father | Shahaji |

| Mother | Jijabai |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Signature | |

Shivaji I (Shivaji Shahaji Bhonsale; Marathi pronunciation: [ʃiʋaːd͡ʒiˑ bʱoˑs(ə)leˑ]; c. 19 February 1630 – 3 April 1680[7]) was an Indian ruler and a member of the Bhonsle Dynasty.[8] Shivaji carved out his own independent kingdom from the declining Adilshahi Sultanate of Bijapur that formed the genesis of the Maratha Empire. In 1674, he was formally crowned the Chhatrapati of his realm at Raigad Fort.[9]

Over the course of his life, Shivaji engaged in both alliances and hostilities with the Mughal Empire, the Sultanate of Golkonda, the Sultanate of Bijapur and the European colonial powers. Shivaji's military forces expanded the Maratha sphere of influence, capturing and building forts, and forming a Maratha navy. Shivaji established a competent and progressive civil administration with well-structured administrative institutions. He revived ancient Hindu political traditions, court conventions and promoted the use of the Marathi and Sanskrit languages, replacing Persian at court and in administration.[9][10] Praised for his chivalrous treatment of women,[11] Shivaji employed people of all castes and religions, including Muslims[12] and Europeans, in his administration and armed forces.[13]

Shivaji's legacy was to vary by observer and time, but nearly two centuries after his death he began to take on increased importance with the emergence of the Indian independence movement, as many Indian nationalists elevated him as a proto-nationalist and hero of the Hindus.[14][15][16]

Early life

Shivaji was born in the hill-fort of Shivneri, near the city of Junnar, which is now in Pune district. Scholars disagree on his date of birth; the Government of Maharashtra lists 19 February as a holiday commemorating Shivaji's birth (Shivaji Jayanti).[a][23][24] Shivaji was named after a local deity, the Goddess Shivai Devi.[25][26]

Shivaji belonged to a Maratha family of the Bhonsle clan.[27] Shivaji's father, Shahaji Bhonsle, was a Maratha general who served the Deccan Sultanates.[28] His mother was Jijabai, the daughter of Lakhuji Jadhavrao of Sindhkhed, a Mughal-aligned sardar claiming descent from a Yadav royal family of Devagiri.[29][30] His paternal grandfather Maloji (1552–1597) was an influential general of Ahmadnagar Sultanate,

and was awarded the epithet of "Raja". He was given deshmukhi rights of Pune, Supe, Chakan, and Indapur to provide for military expenses. He was also given Fort Shivneri for his family's residence (c. 1590).[31][32]

At the time of Shivaji's birth, power in the Deccan was shared by three Islamic sultanates: Bijapur, Ahmednagar, and Golkonda. Shahaji often changed his loyalty between the Nizamshahi of Ahmadnagar, the Adilshah of Bijapur and the Mughals, but always kept his jagir (fiefdom) at Pune and his small army.[28]

Conflict with Bijapur Sultanate

Background and context

In 1636, the Adil Shahi sultanate of Bijapur invaded the kingdoms to its south.[8] The sultanate had recently become a tributary state of the Mughal empire.[8][33] It was being helped by Shahaji, who at the time was a chieftain in the Maratha uplands of western India. Shahaji was looking for opportunities of rewards of jagir land in the conquered territories, the taxes on which he could collect as an annuity.[8]

Shahaji was a rebel from brief Mughal service. Shahaji's campaigns against the Mughals, supported by the Bijapur government, were generally unsuccessful. He was constantly pursued by the Mughal army, and Shivaji and his mother Jijabai had to move from fort to fort.[34]

In 1636, Shahaji joined in the service of Bijapur and obtained Poona as a grant. Shahaji, being deployed in Bangalore by the Bijapuri ruler Adilshah, appointed Dadoji Kondadeo as Poona's administrator. Shivaji and Jijabai settled in Poona.[35] Kondadeo died in 1647 and Shivaji took over its administration. One of his first acts directly challenged the Bijapuri government.[36]

Independent generalship

In 1646, 16-year-old Shivaji captured the Torna Fort, taking advantage of the confusion prevailing in the Bijapur court due to the illness of Sultan Mohammed Adil Shah, and seized the large treasure he found there.[37][38] In the following two years, Shivaji took several important forts near Pune, including Purandar, Kondhana, and Chakan. He also brought areas east of Pune around Supa, Baramati, and Indapur under his direct control. He used the treasure found at Torna to build a new fort named Rajgad. That fort served as the seat of his government for over a decade.[37] After this, Shivaji turned west to the Konkan and took possession of the important town of Kalyan. The Bijapur government took note of these happenings and sought to take action. On 25 July 1648, Shahaji was imprisoned by a fellow Maratha sardar called Baji Ghorpade, under the orders of the Bijapur government, in a bid to contain Shivaji.[39]

Shahaji was released in 1649, after the capture of Jinji secured Adilshah's position in Karnataka. During 1649–1655, Shivaji paused in his conquests and quietly consolidated his gains.[40] Following his father's release, Shivaji resumed raiding, and in 1656, under controversial circumstances, killed Chandrarao More, a fellow Maratha feudatory of Bijapur, and seized the valley of Javali, near the present-day hill station of Mahabaleshwar.[41] The conquest of Javali allowed Shivaji to extend his raids into south and southwest Maharashtra. In addition to the Bhonsle and the More families, many others—including Sawant of Sawantwadi, Ghorpade of Mudhol, Nimbalkar of Phaltan, Shirke, Mane, and Mohite—also served Adilshahi of Bijapur, many with Deshmukhi rights. Shivaji adopted different strategies to subdue these powerful families, such as forming marital alliances, dealing directly with village Patils to bypass the Deshmukhs, or subduing them by force.[42] Shahaji in his later years had an ambivalent attitude to his son, and disavowed his rebellious activities.[43] He told the Bijapuris to do whatever they wanted with Shivaji. Shahaji died around 1664–1665 in a hunting accident.

Combat with Afzal Khan

The Bijapur sultanate was displeased with their losses to Shivaji's forces, with their vassal Shahaji disavowing his son's actions. After a peace treaty with the Mughals, and the general acceptance of the young Ali Adil Shah II as the sultan, the Bijapur government became more stable, and turned its attention towards Shivaji.[44] In 1657, the sultan, or more likely his mother and regent, sent Afzal Khan, a veteran general, to arrest Shivaji. Before engaging him, the Bijapuri forces desecrated the Tulja Bhavani Temple, a holy site for Shivaji's family, and the Vithoba temple at Pandharpur, a major pilgrimage site for Hindus.[45][46][47]

Pursued by Bijapuri forces, Shivaji retreated to Pratapgad fort, where many of his colleagues pressed him to surrender.[48] The two forces found themselves at a stalemate, with Shivaji unable to break the siege, while Afzal Khan, having a powerful cavalry but lacking siege equipment, was unable to take the fort. After two months, Afzal Khan sent an envoy to Shivaji suggesting the two leaders meet in private, outside the fort, for negotiations.[49][50]

The two met in a hut in the foothills of Pratapgad fort on 10 November 1659. The arrangements had dictated that each come armed only with a sword, and attended by one follower. Shivaji, suspecting Afzal Khan would arrest or attack him,[51][b] wore armour beneath his clothes, concealed a bagh nakh (metal "tiger claw") on his left arm, and had a dagger in his right hand.[53] What transpired is not known with historical certainty, mainly Maratha legends tell the tale; however, it is agreed that the two wound up in a physical struggle that proved fatal for Khan.[c] Khan's dagger failed to pierce Shivaji's armour, but Shivaji disemboweled him; Shivaji then fired a cannon to signal his hidden troops to attack the Bijapuri army.[55]

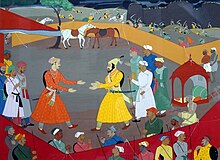

In the ensuing Battle of Pratapgarh, Shivaji's forces decisively defeated the Bijapur Sultanate's forces. More than 3,000 soldiers of the Bijapur army were killed; and one sardar of high rank, two sons of Afzal Khan, and two Maratha chiefs were taken prisoner.[56] After the victory, a grand review was held by Shivaji below Pratapgarh. The captured enemy, both officers and men, were set free and sent back to their homes with money, food, and other gifts. Marathas were rewarded accordingly.[56]

Siege of Panhala

Having defeated the Bijapuri forces sent against him, Shivaji and his army marched towards the Konkan coast and Kolhapur, seizing Panhala fort, and defeating Bijapuri forces sent against them, under Rustam Zaman and Fazl Khan, in 1659.[57] In 1660, Adilshah sent his general Siddi Jauhar to attack Shivaji's southern border, in alliance with the Mughals who planned to attack from the north. At that time, Shivaji was encamped at Panhala fort with his forces. Siddi Jauhar's army besieged Panhala in mid-1660, cutting off supply routes to the fort. During the bombardment of Panhala, Siddi Jauhar purchased grenades from the English at Rajapur, and also hired some English artillerymen to assist in his bombardment of the fort, conspicuously flying a flag used by the English. This perceived betrayal angered Shivaji, who in December would retaliate by plundering the English factory at Rajapur and capturing four of the owners, imprisoning them until mid-1663.[58]

After months of siege, Shivaji negotiated with Siddi Jauhar and handed over the fort on 22 September 1660, withdrawing to Vishalgad;[59] Shivaji would retake Panhala in 1673.[60]

Battle of Pavan Khind

Shivaji escaped from Panhala by cover of night, and as he was pursued by the enemy cavalry, his Maratha sardar Baji Prabhu Deshpande of Bandal Deshmukh, along with 300 soldiers, volunteered to fight to the death to hold back the enemy at Ghod Khind ("horse ravine") to give Shivaji and the rest of the army a chance to reach the safety of the Vishalgad fort.[61]

In the ensuing Battle of Pavan Khind, the smaller Maratha force held back the larger enemy to buy time for Shivaji to escape. Baji Prabhu Deshpande was wounded but continued to fight until he heard the sound of cannon fire from Vishalgad,[27] signalling Shivaji had safely reached the fort, on the evening of 13 July 1660.[62] Ghod Khind (khind meaning "a narrow mountain pass") was later renamed Paavan Khind ("sacred pass") in honour of Bajiprabhu Deshpande, Shibosingh Jadhav, Fuloji, and all other soldiers who fought there.[62]

Conflict with the Mughals

Until 1657, Shivaji maintained peaceful relations with the Mughal Empire. Shivaji offered his assistance to Aurangzeb, the son of the Mughal Emperor and viceroy of the Deccan, in conquering Bijapur, in return for formal recognition of his right to the Bijapuri forts and villages in his possession. Dissatisfied with the Mughal response, and receiving a better offer from Bijapur, he launched a raid into the Mughal Deccan.[63] Shivaji's confrontations with the Mughals began in March 1657, when two of Shivaji's officers raided the Mughal territory near Ahmednagar.[64] This was followed by raids in Junnar, with Shivaji carrying off 300,000 hun in cash and 200 horses.[65] Aurangzeb responded to the raids by sending Nasiri Khan, who defeated the forces of Shivaji at Ahmednagar. However, Aurangzeb's countermeasures against Shivaji were interrupted by the rainy season and his battles with his brothers over the succession to the Mughal throne, following the illness of the emperor Shah Jahan.[66]

Attacks on Shaista Khan and Surat

At the request of Badi Begum of Bijapur, Aurangzeb, now the Mughal emperor, sent his maternal uncle Shaista Khan, with an army numbering over 150,000, along with a powerful artillery division, in January 1660 to attack Shivaji in conjunction with Bijapur's army led by Siddi Jauhar. Shaista Khan, with his better equipped and well provisioned army of 80,000 seized Pune. He also took the nearby fort of Chakan, besieging it for a month and a half before breaching the walls.[67] He established his residence at Shivaji's palace of Lal Mahal.[68]

On the night of 5 April 1663, Shivaji led a daring night attack on Shaista Khan's camp.[69] He, along with 400 men, attacked Shaista Khan's mansion, broke into Khan's bedroom and wounded him. Khan lost three fingers.[70] In the scuffle, Shaista Khan's son and several wives, servants, and soldiers were killed.[71] The Khan took refuge with the Mughal forces outside of Pune, and Aurangzeb punished him for this embarrassment with a transfer to Bengal.[72]

In retaliation for Shaista Khan's attacks, and to replenish his now-depleted treasury, in 1664 Shivaji sacked the port city of Surat, a wealthy Mughal trading centre.[73] On 13 February 1665, he also conducted a naval raid on Portuguese-held Basrur in present-day Karnataka, and gained a large plunder.[74][75]

Treaty of Purandar

The attacks on Shaista Khan and Surat enraged Aurangzeb. In response, he sent the Rajput general Jai Singh I with an army numbering around 15,000 to defeat Shivaji.[76] Throughout 1665, Jai Singh's forces pressed Shivaji, with their cavalry razing the countryside, and besieging Shivaji's forts. The Mughal commander succeeded in luring away several of Shivaji's key commanders, and many of his cavalrymen, into Mughal service. By mid-1665, with the fortress at Purandar besieged and near capture, Shivaji was forced to come to terms with Jai Singh.[76]

In the Treaty of Purandar, signed by Shivaji and Jai Singh on 11 June 1665, Shivaji agreed to give up 23 of his forts, keeping 12 for himself, and pay compensation of 400,000 gold hun to the Mughals.[77] Shivaji agreed to become a vassal of the Mughal empire, and to send his son Sambhaji, along with 5,000 horsemen, to fight for the Mughals in the Deccan, as a mansabdar.[78][79]

Arrest in Agra and escape

In 1666, Aurangzeb summoned Shivaji to Agra (though some sources instead state Delhi), along with his nine-year-old son Sambhaji. Aurangzeb's planned to send Shivaji to Kandahar, now in Afghanistan, to consolidate the Mughal empire's northwestern frontier. However, on 12 May 1666, Shivaji was made to stand at court alongside relatively low-ranking nobles, men he had already defeated in battle.[80] Shivaji took offence, stormed out,[81] and was promptly placed under house arrest. Ram Singh, son of Jai Singh, guaranteed custody of Shivaji and his son.[82]

Shivaji's position under house arrest was perilous, as Aurangzeb's court debated whether to kill him or continue to employ him. Jai Singh, having assured Shivaji of his personal safety, tried to influence Aurangzeb's decision.[83] Meanwhile, Shivaji hatched a plan to free himself. He sent most of his men back home and asked Ram Singh to withdraw his guarantees to the emperor for the safe custody of himself and his son. He surrendered to Mughal forces.[84][85] Shivaji then pretended to be ill and began sending out large baskets packed with sweets to be given to the Brahmins and poor as penance.[86][87][88][89] On 17 August 1666, by putting himself in one of the large baskets and his son Sambhaji in another, Shivaji escaped and left Agra.[90][91][92][d]

Peace with the Mughals

After Shivaji's escape, hostilities with the Mughals ebbed, with the Mughal sardar Jaswant Singh acting as an intermediary between Shivaji and Aurangzeb for new peace proposals.[94] Between 1666 and 1668, Aurangzeb conferred the title of raja on Shivaji. Sambhaji was also restored as a Mughal mansabdar with 5,000 horses. Shivaji at that time sent Sambhaji, with general Prataprao Gujar, to serve with the Mughal viceroy in Aurangabad, Prince Mu'azzam. Sambhaji was also granted territory in Berar for revenue collection.[95] Aurangzeb also permitted Shivaji to attack Bijapur, ruled by the decaying Adil Shahi dynasty; the weakened Sultan Ali Adil Shah II sued for peace and granted the rights of sardeshmukhi and chauthai to Shivaji.[96]

Reconquest

The peace between Shivaji and the Mughals lasted until 1670, after which Aurangzeb became suspicious of the close ties between Shivaji and Mu'azzam, who he thought might usurp his throne, and may even have been receiving bribes from Shivaji.[97][98] Also at that time, Aurangzeb, occupied in fighting the Afghans, greatly reduced his army in the Deccan; many of the disbanded soldiers quickly joined Maratha service.[99] The Mughals also took away the jagir of Berar from Shivaji to recover the money lent to him a few years earlier.[100] In response, Shivaji launched an offensive against the Mughals and in a span of four months recovered a major portion of the territories that had been surrendered to them.[101]

Shivaji sacked Surat for a second time in 1670; the English and Dutch factories were able to repel his attack, but he managed to sack the city itself, including plundering the goods of a Muslim prince from Mawara-un-Nahr, who was returning from Mecca. Angered by the renewed attacks, the Mughals resumed hostilities with the Marathas, sending a force under Daud Khan to intercept Shivaji on his return home from Surat; this force was defeated in the Battle of Vani-Dindori near present-day Nashik.[102]

In October 1670, Shivaji sent his forces to harass the English at Bombay; as they had refused to sell him war materiel, his forces blocked English woodcutting parties from leaving Bombay. In September 1671, Shivaji sent an ambassador to Bombay, again seeking materiel, this time for the fight against Danda-Rajpuri. The English had misgivings of the advantages Shivaji would gain from this conquest, but also did not want to lose any chance of receiving compensation for his looting their factories at Rajapur. The English sent Lieutenant Stephen Ustick to treat with Shivaji, but negotiations failed over the issue of the Rajapur indemnity. Numerous exchanges of envoys followed over the coming years, with some agreement as to the arms issues in 1674, but Shivaji was never to pay the Rajapur indemnity before his death, and the factory there dissolved at the end of 1682.[103]

Battles of Umrani and Nesari

In 1674, Prataprao Gujar, the sarnaubat (commander-in-chief of the Maratha forces), was sent to push back the invading force led by the Bijapuri general, Bahlol Khan. Prataprao's forces defeated and captured the opposing general in the battle, after cutting-off their water supply by encircling a strategic lake, which prompted Bahlol Khan to sue for peace. In spite of Shivaji's specific warnings against doing so, Prataprao released Bahlol Khan, who started preparing for a fresh invasion.[104]

Shivaji sent a letter to Prataprao, expressing his displeasure and refusing him an audience until Bahlol Khan was re-captured. Upset by this rebuke, Prataprao found Bahlol Khan and charged his position with only six other horsemen, leaving his main force behind, and was killed in combat. Shivaji was deeply grieved on hearing of Prataprao's death, and arranged for the marriage of his second son, Rajaram, to Prataprao's daughter. Prataprao was succeeded by Hambirrao Mohite, as the new sarnaubat. Raigad Fort was newly built by Hiroji Indulkar, as a capital of the nascent Maratha kingdom.[105]

Coronation

Shivaji had acquired extensive lands and wealth through his campaigns, but lacking a formal title, he was still technically a Mughal zamindar or the son of a Bijapuri jagirdar, with no legal basis to rule his de facto domain. A kingly title could address this and also prevent any challenges by other Maratha leaders, who were his equals.[e] Such a title would also provide the Hindu Marathis with a fellow Hindu sovereign in a region otherwise ruled by Muslims.[107]

The preparation for a proposed coronation began in 1673. However, some controversies delayed the coronation by almost a year.[108] One controversy erupted amongst the Brahmins of Shivaji's court: they refused to crown Shivaji as a king because that status was reserved for those of the kshatriya varna (warrior class) in Hindu society.[109] Shivaji was descended from a line of headmen of farming villages, and the Brahmins accordingly categorised him as a Maratha, not a Kshatriya.[110][111] They noted that Shivaji had never had a sacred thread ceremony, and did not wear the thread, such as a kshatriya would.[112] Shivaji summoned Gaga Bhatt, a pandit of Varanasi, who stated that he had found a genealogy proving that Shivaji was descended from the Sisodias, and thus indeed a kshatriya, albeit one in need of the ceremonies befitting his rank.[113] To enforce this status, Shivaji was given a sacred thread ceremony, and remarried his spouses under the Vedic rites expected of a kshatriya.[114][115] However, according to historical evidence, Shivaji's claim to Rajput, and specifically of Sisodia ancestry, may be seen as being anything from tenuous, at best, to purely inventive.[116]

On 28 May, Shivaji did penance for his and his ancestors' not observing Kshatriya rites for so long. Then he was invested by Gaga Bhatt with the sacred thread.[117] On the insistence of other Brahmins, Gaga Bhatt omitted the Vedic chant and initiated Shivaji into a modified form of the life of the twice-born, instead of putting him on a par with the Brahmins. Next day, Shivaji made atonement for the sins, deliberate or accidental, committed in his own lifetime.[118] He was weighed separately against seven metals including gold, silver, and several other articles, such fine linen, camphor, salt, sugar etc. All these articles, along with a lakh (one hundred thousand) of hun, were distributed among the Brahmins. According to Sarkar, even this failed to satisfy the greed of the Brahmins. Two of the learned Brahmins pointed out that Shivaji, while conducting his raids, had killed Brahmins, cows, women, and children. He could be cleansed of these sins for a price of Rs. 8,000, which Shivaji paid.[118] The total expenditure for feeding the assemblage, general almsgiving, throne, and ornaments approached 1.5 million rupees.[119]

On 6 June 1674, Shivaji was crowned king of the Maratha Empire (Hindavi Swaraj) in a lavish ceremony at Raigad fort.[120][121] In the Hindu calendar it was the 13th day (trayodashi) of the first fortnight of the month of Jyeshtha in the year 1596.[122] Gaga Bhatt officiated, pouring water from a gold vessel filled with the waters of the seven sacred rivers—Yamuna, Indus, Ganges, Godavari, Narmada, Krishna, and Kaveri—over Shivaji's head, and chanted the Vedic coronation mantras. After the ablution, Shivaji bowed before his mother, Jijabai, and touched her feet. Nearly fifty thousand people gathered at Raigad for the ceremonies.[123][124] Shivaji was entitled Shakakarta ("founder of an era")[1] and Chhatrapati ("Lord of the Umbrella"). He also took the title of Haindava Dharmodhhaarak (protector of the Hindu faith)[2] and Kshatriya Kulavantas:[125][126][127] Kshatriya being the varna[f] of Hinduism and kulavantas meaning the 'head of the kula, or clan'.[128]

Shivaji's mother died on 18 June 1674. The Marathas summoned Nischal Puri Goswami, a tantric priest, who declared that the original coronation had been held under inauspicious stars, and a second coronation was needed. This second coronation, on 24 September 1674, mollified those who still believed that Shivaji was not qualified for the Vedic rites of his first coronation, by being a less controversial ceremony.[129][130][131]

Conquest in southern India

Beginning in 1674, the Marathas undertook an aggressive campaign, raiding Khandesh (October), capturing Bijapuri Ponda (April 1675), Karwar (mid-year), and Kolhapur (July).[132] In November, the Maratha navy skirmished with the Siddis of Janjira, but failed to dislodge them.[133] Having recovered from an illness, and taking advantage of a civil war that had broken out between the Deccanis and the Afghans at Bijapur, Shivaji raided Athani in April 1676.[134]

In the run-up to his expedition, Shivaji appealed to a sense of Deccani patriotism, that Southern India was a homeland that should be protected from outsiders.[135][136] His appeal was somewhat successful, and in 1677 Shivaji visited Hyderabad for a month and entered into a treaty with the Qutubshah of the Golkonda sultanate, who agreed to renounce his alliance with Bijapur and jointly oppose the Mughals. In 1677, Shivaji invaded Karnataka with 30,000 cavalry and 40,000 infantry, backed by Golkonda artillery and funding.[137] Proceeding south, Shivaji seized the forts of Vellore and Gingee;[138] the latter would later serve as a capital of the Marathas during the reign of his son Rajaram I.[139]

Shivaji intended to reconcile with his half-brother Venkoji (Ekoji I), Shahaji's son by his second wife, Tukabai (née Mohite), who ruled Thanjavur (Tanjore) after Shahaji. The initially promising negotiations were unsuccessful, so whilst returning to Raigad, Shivaji defeated his half-brother's army on 26 November 1677 and seized most of his possessions on the Mysore plateau. Venkoji's wife Dipa Bai, whom Shivaji deeply respected, took up new negotiations with Shivaji and also convinced her husband to distance himself from his Muslim advisors. In the end, Shivaji consented to turn over to her and her female descendants many of the properties he had seized, with Venkoji consenting to a number of conditions for the proper administration of the territories and maintenance of Shahji's tomb (samadhi).[140][141]

Death and succession

The question of Shivaji's heir-apparent was complicated. Shivaji confined his son to Panhala Fort in 1678, only to have the prince escape with his wife and defect to the Mughals for a year. Sambhaji then returned home, unrepentant, and was again confined to Panhala Fort.[142]

Shivaji died around 3–5 April 1680 at the age of 50,[143] on the eve of Hanuman Jayanti. The cause of Shivaji's death is disputed. British records states that Shivaji died of bloody flux, after being sick for 12 days.[g] In a contemporary work in Portuguese, in the Biblioteca Nacional de Lisboa, the recorded cause of death of Shivaji is anthrax.[145][146] However, Krishnaji Anant Sabhasad, author of Sabhasad Bakhar, a biography of Shivaji has mentioned fever as the cause of death.[147][146] Putalabai, the childless eldest of the surviving wives of Shivaji committed sati by jumping into his funeral pyre. Another surviving spouse, Sakwarbai, was not allowed to follow suit because she had a young daughter.[142] There were also allegations, though doubted by later scholars, that his second wife Soyarabai had poisoned him in order to put her 10-year-old son Rajaram on the throne.[148]

After Shivaji's death, Soyarabai made plans, with various ministers, to crown her son Rajaram rather than her stepson Sambhaji. On 21 April 1680, ten-year-old Rajaram was installed on the throne. However, Sambhaji took possession of Raigad Fort after killing the commander, and on 18 June acquired control of Raigad, and formally ascended the throne on 20 July.[149] Rajaram, his mother Soyarabai and wife Janki Bai were imprisoned, and Soyrabai was executed on charges of conspiracy that October.[150]

Aurangzeb's Campaign Against Marathas And Aftermath

In 1681, soon after Shivaji's death, Aurangzeb launched an offensive in the South, to capture territories held by the Marathas, the Adil Shahi of Bijapur, and Qutb Shahi of Golconda. He was successful in obliterating the Adil Shahi and Qutb Shahi dynasties, but could not subdue the Marathas. Better known as the Mughal–Maratha Wars, this campaign nominally increased the size of Mughal Empire, but ended in a strategic defeat and had a ruinous effect on Mughal Empire. Aurangzeb spent 27 years in Deccan, but ultimately failed to achieve his objective of conquering the Marathas, while, draining the Mughal treasury, and almost irreparably damaging the strength and morale of the Mughal army. According to contemporary sources, about 2.5 million of Aurangzeb's army were killed during the Mughal–Maratha Wars (100,000 annually over a quarter-century), while 2 million civilians in war-torn lands died due to drought, plague, and famine.[151][152][153]

Shahu, a grandson of Shivaji and son of Sambhaji, was kept prisoner by Aurangzeb during the 27-year conflict. After the latter's death, his successor released Shahu. After a brief power struggle with his aunt Tarabai over the succession, Shahu ruled the Maratha Empire from 1707 to 1749. Early in his reign, he appointed Balaji Vishwanath, and later his descendants, as Peshwas (prime ministers) of the Maratha Empire. The empire expanded greatly under the leadership of Balaji's son, Peshwa Bajirao I and grandson Peshwa Balaji Bajirao[citation needed].

In a bid to effectively manage the large empire, Shahu and the Peshwas gave semi-autonomy to the strongest of the lords, Gaekwads of Baroda, the Holkars of Indore and Malwa, the Scindias of Gwalior, and Bhonsales of Nagpur, thus creating the Maratha Confederacy.[154]

Legacy

Shivaji's greatest legacy was laying the foundation for the Maratha Empire, which played a significant role in undermining the military and economic strength and prestige of the Mughal Empire.

Soon after Aurangzeb's death in 1707, Marathas started to capture Mughal dominions. By 1734, Marathas were firmly established in Malwa. By 1737 Marathas had carried out raids as far as Bundelkhand, Rajputana, the Doab, and defeated an imperial army outside walls of Delhi.[155] Facing defeat and starvation of his army in 1738, the Nizam of Hyderabad, acting on the authority of the Mughal emperor, recognised Marathas as rulers of Malwa and sovereign of all territories between Narmada and Chambal.[156] Stewart Gordon writes regarding the northward march of Marathas:[156]

In the 1750s, the "frontier" extended north to Delhi. In this period, the Mughal government directly controlled little territory further than fifty miles from the capital. Even this was fiercely fought over. Jats and Rohillas disputed for the territory; factions fought for the throne, and the Afghan king, Ahmad Shah Abdali, periodically descended on the capital.

...

For the Marathas, probably the two most significant events of the whole chaotic period in Delhi were a treaty in 1752, which made them protector of the Mughal throne (and gave them the right to collect chauth in the Punjab), and the civil war of 1753, by which the Maratha nominee ended up on the Mughal throne.- (Cambridge History of India Vol. 2 Part 4 pp. 138 - 139)

At its peak, the Maratha empire stretched from modern-day Maharashtra, in the south, to the Sutlej river, in the north, and to Orissa, in the east. In 1761, the Maratha army lost the Third Battle of Panipat to Ahmed Shah Durrani of the Afghan Empire, which is considered a big setback for the Marathas. However, the Marathas soon recovered. Ten years after Panipat, Marathas regained influence in North India during the rule of Madhav Rao II.[157]

In the first half of the 19th century, the British East India Company was increasing its strength in India. Charles Metcalfe, a British official and later acting governor-general, said in 1806:[158]

India contains no more than two great powers, British and Maratha, and every other state acknowledges the influence of one or the other. Every inch that we recede will be occupied by them.

The Marathas remained the pre-eminent power in India until their defeat by the British in the Second and Third Anglo-Maratha wars (1805–1818), which left the company the dominant power in most of India.[159][160]

Governance

Ashta Pradhan Mandal

The Council of Eight Ministers, or Ashta Pradhan Mandal, was an administrative and advisory council set up by Shivaji.[161][162] It consisted of eight ministers who regularly advised Shivaji on political and administrative matters. The eight ministers were as follows:[147]

| Minister | Duty |

|---|---|

| Peshwa or Prime Minister | General administration |

| Amatya or Finance Minister | Maintaining public accounts |

| Mantri or Chronicler | Maintaining court records |

| Summant or Dabir or Foreign Secretary | All matters related to relationships with other states |

| Sachiv or Shurn Nawis or Home Secretary | Managing correspondence of the king |

| Panditrao or Ecclesiastical Head | Religious matters |

| Nyayadhis or Chief Justice | Civil and military justice |

| Senapati/Sari Naubat or Commander-in-Chief | All matters related to army of the king |

Except the Panditrao and Nyayadhis, all other ministers held military commands, their civil duties often being performed by deputies.[147][161]

Promotion of Marathi and Sanskrit

At his court, Shivaji replaced Persian, the common courtly language in the region, with Marathi, and emphasised Hindu political and courtly traditions. Shivaji's reign stimulated the deployment of Marathi as a systematic tool of description and understanding.[163] Shivaji's royal seal was in Sanskrit. Shivaji commissioned one of his officials to make a comprehensive lexicon to replace Persian and Arabic terms with their Sanskrit equivalents. This led to the production of the Rājavyavahārakośa, the thesaurus of state usage in 1677.[10]

Religious policy

Many modern commentators have deemed Shivaji's religious policies as tolerant. While encouraging Hinduism, Shivaji not only allowed Muslims to practice without harassment, but supported their ministries with endowments.[164] When Aurangzeb imposed the Jizya tax on non-Muslims on 3 April 1679, Shivaji wrote an admonishing letter to Aurangzeb criticising his tax policy. He wrote:

In strict justice, the Jizya is not at all lawful. If you imagine piety in oppressing and terrorising the Hindus, you ought to first levy the tax on Raj Singh I, who is the head of Hindus. But to oppress ants and flies is not at all valour nor spirit. If you believe in Quran, God is the lord of all men and not just of Muslims only. Verily, Islam and Hinduism are terms of contrast. They are used by the true Divine Painter for blending the colours and filling in the outlines. If it is a mosque, the call to prayer is chanted in remembrance of God. If it is a temple, the bells are rung in yearning for God alone. To show bigotry to any man's religion and practices is to alter the words of the Holy Book.[165][166]

Noting that Shivaji had stemmed the spread of the neighbouring Muslim states, his contemporary, the poet Kavi Bhushan stated:

Had not there been Shivaji, Kashi would have lost its culture, Mathura would have been turned into a mosque and all would have been circumcised.[167]

However, Gijs Kruijtzer, in his book Xenophobia in Seventeenth-Century India argues that the roots of modern communalism (the antagonism between Hindu and Muslim "communities") first appeared in the decade 1677–1687, in the interplay between Shivaji and the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb (though Shivaji died in 1680).[168] [page needed] During the sack of Surat in 1664, Shivaji was approached by Ambrose, a Capuchin friar who asked him to spare the city's Christians. Shivaji left the Christians untouched, saying "the Frankish Padrys are good men."[169]

Shivaji was not attempting to create a universal Hindu rule. He was tolerant of different religions and believed in syncretism. He urged Aurangzeb to act like Akbar in according respect to Hindu beliefs and places. Shivaji had little trouble forming alliances with the surrounding Muslim nations, even against Hindu powers. He also did not join forces with certain other Hindu powers fighting the Mughals, such as the Rajputs.[h] His own army had Muslim leaders from early on. The first Pathan unit was formed in 1656. His admiral, Darya Sarang, was a Muslim.[171]

-

Bakhar dedicated to Shivaji

-

Writings of Modi Script. line 2 is from the time of Shivaji

Ramdas

Shivaji was a contemporary of Samarth Ramdas. Historian Stewart Gordon concludes about their relationship:

Older Maratha histories asserted that Shivaji was a close follower of Ramdas, a Brahmin teacher, who guided him in an orthodox Hindu path; recent research has shown that Shivaji did not meet or know Ramdas until late in his life. Rather, Shivaji followed his own judgement throughout his remarkable career.[42]

Seal

Seals were a means to confer authenticity on official documents. Shahaji and Jijabai had Persian seals. But Shivaji, right from the beginning, used Sanskrit for his seal.[10] The seal proclaims: "This seal of Shiva, son of Shah, shines forth for the welfare of the people and is meant to command increasing respect from the universe like the first phase of the moon."[172]

Shivaji's mode of warfare

Shivaji maintained a small but effective standing army. The core of Shivaji's army consisted of peasants of Maratha and Kunbi castes.[173] Shivaji was aware of the limitations of his army. He realised that conventional warfare methods were inadequate to confront the big, well-trained cavalry of the Mughals, which was equipped with field artillery. As a result, Shivaji mastered guerilla tactics which became known as Ganimi Kawa in the Marathi language.[174][175] His strategies consistently perplexed and defeated armies sent against him. He realized that the most vulnerable point of the large, slow-moving armies of the time was supply. He utilised knowledge of the local terrain and the superior mobility of his light cavalry to cut off supplies to the enemy.[176] Shivaji refused to confront the enemy in pitched battles. Instead, he lured the enemies into difficult hills and jungles of his own choosing, catching them at a disadvantage and routing them. Shivaji did not adhere to a particular tactic but used several methods to undermine his enemies, as required by circumstances, such as sudden raids, sweeps and ambushes, and psychological warfare.[177]

Shivaji was contemptuously called a "Mountain Rat" by Aurangzeb and his generals, because of his guerilla tactics of attacking enemy forces and then retreating into his mountain forts.[178][179][180]

Military

Shivaji demonstrated great skill in creating his military organisation, which lasted until the demise of the Maratha Empire. His strategy rested on leveraging his ground forces, naval forces, and series of forts across his territory. The Maval infantry served as the core of his ground forces (reinforced by Telangi musketeers from Karnataka) and supported by Maratha cavalry. His artillery was relatively underdeveloped and reliant on European suppliers, further inclining him to a very mobile form of warfare.[181]

Hill forts

Hill forts played a key role in Shivaji's strategy. Ramchandra Amatya, one of Shivaji's ministers, describes the achievement of Shivaji by saying that his empire was created from forts.[182] Shivaji captured important Adilshahi forts at Murambdev (Rajgad), Torna, Kondhana (Sinhagad), and Purandar. He also rebuilt or repaired many forts in advantageous locations.[183] In addition, Shivaji built a number of forts, numbering 111 according to some accounts, but it is likely the actual number "did not exceed 18."[184] The historian Jadunath Sarkar assessed that Shivaji owned some 240–280 forts at the time of his death.[185] Each was placed under three officers of equal status, lest a single traitor be bribed or tempted to deliver it to the enemy. The officers acted jointly and provided mutual checks and balances.[186]

Aware of the need for naval power to maintain control along the Konkan coast, Shivaji began to build his navy in 1657 or 1659, with the purchase of twenty galivats from the Portuguese shipyards of Bassein.[187] Marathi chronicles state that at its height his fleet counted some 400 warships, although contemporary English chronicles counter that the number never exceeded 160.[188]

With the Marathas being accustomed to a land-based military, Shivaji widened his search for qualified crews for his ships, taking on lower-caste Hindus of the coast who were long familiar with naval operations (the famed "Malabar pirates"), as well as Muslim mercenaries.[188] Noting the power of the Portuguese navy, Shivaji hired a number of Portuguese sailors and Goan Christian converts, and made Rui Leitao Viegas commander of his fleet. Viegas was later to defect back to the Portuguese, taking 300 sailors with him.[189]

Shivaji fortified his coastline by seizing coastal forts and refurbishing them. He built his first marine fort at Sindhudurg, which was to become the headquarters of the Maratha navy.[190] The navy itself was a coastal navy, focused on travel and combat in the littoral areas, and not intended for the high seas.[191][192]

Depictions and interpretations of Shivaji

Shivaji was well known for his strong religious convictions, warrior code of ethics, and exemplary character.[193]

Contemporaneous view

Shivaji was admired for his heroic exploits and clever stratagems in the contemporary accounts of English, French, Dutch, Portuguese, and Italian writers.[194] Contemporary English writers compared him with Alexander, Hannibal, and Julius Caesar.[195] The French traveller Francois Bernier wrote in his Travels in Mughal India:[196]

I forgot to mention that during pillage of Sourate, Seva-Gy, the Holy Seva-Gi! respected the habitation of the Reverend Father Ambrose, the Capuchin missionary. 'The Frankish Padres are good men', he said 'and shall not be attacked.' He spared also the house of a deceased Delale or Gentile broker, of the Dutch, because assured that he had been very charitable while alive.

Mughal depictions of Shivaji were largely negative, referring to him simply as "Shiva" without the honorific "-ji". One Mughal writer in the early 1700s described Shivaji's death as kafir bi jahannum raft (lit. 'the infidel went to Hell').[197] His chivalrous treatment of enemies and women has been praised by Mughal authors, including Khafi Khan. Jadunath Sarkar writes:[11]

His chivalry to women and strict enforcement of morality in his camp was a wonder in that age and has extorted the admiration of hostile critics like Khafi Khan.

Early depictions

The earliest depictions of Shivaji by authors not affiliated with Maratha court in Maharashtra are to be found in the bakhars that depict Shivaji as an almost divine figure, an ideal Hindu king who overthrew Muslim dominion. The current academic consensus is that while these Bakhars are important for understanding how Shivaji was viewed in his time, they must be correlated with other sources to decide historical truth. Sabhasad Bakhar and 91 Kalami Bakhar are considered the most reliable of all bakhars by scholars.[76]

Nineteenth century

James Grant Duff, a British administrator, published his 3-volume work on History of Marathas in 1863.[198] This work is mostly a chronological sequence of events and more of a political history with little to no insight about other aspects of Maharashtra's history.[76]

In the mid–19th century, Marathi social reformer Jyotirao Phule wrote his interpretation of the Shivaji legend, portraying him as a hero of the shudras and dalits. Phule's 1869 ballad-form story of Shivaji was met with great hostility by the Brahmin-dominated media.[199]

In 1895, the Indian nationalist leader Lokmanya Tilak organised what was to be an annual festival to mark the birthday of Shivaji.[14] He portrayed Shivaji as the "opponent of the oppressor", with possible negative implications concerning the colonial government.[200] Tilak denied any suggestion that his festival was anti-Muslim or disloyal to the government, but simply a celebration of a hero.[201] These celebrations prompted a British commentator in 1906 to note: "Cannot the annals of the Hindu race point to a single hero whom even the tongue of slander will not dare call a chief of dacoits...?"[202]

One of the first commentators to reappraise the critical British view of Shivaji was M. G. Ranade, whose Rise of the Maratha Power (1900) declared Shivaji's achievements as the beginning of modern nation-building. Ranade criticised earlier British portrayals of Shivaji's state as "a freebooting power, which thrived by plunder and adventure, and succeeded only because it was the most cunning and adventurous ... This is a very common feeling with the readers, who derive their knowledge of these events solely from the works of English historians."[203]

In 1919, Sarkar published the seminal Shivaji and His Times, hailed as the most authoritative biography of the king since James Grant Duff's 1826 A History of the Mahrattas. Sarkar was able to read primary sources in Persian, Marathi, and Arabic, but was challenged for his criticism of the "chauvinism" of Marathi historians' views of Shivaji.[204] Likewise, although supporters cheered his depiction of the killing of Afzal Khan as justified, they decried Sarkar's terming as "murder" the killing of the Hindu raja Chandrao More and his clan.[205]

In 1937, Dennis Kincaid, a British civil servant in India, published The Grand Rebel.[206] This book portrays Shivaji as a heroic rebel and a master strategist fighting a much larger Mughal army.[76]

During the independence movement

As political tensions rose in India in the early 20th century, some Indian leaders came to re-work their earlier stances on Shivaji's role. Jawaharlal Nehru had in 1934 noted "Some of the Shivaji's deeds, like the treacherous killing of the Bijapur general, lower him greatly in our estimation." Following a public outcry from Pune intellectuals, Congress leader T. R. Deogirikar noted that Nehru had admitted he was wrong regarding Shivaji, and now endorsed Shivaji as a great nationalist.[207][208]

At the end of the 19th century, Shivaji's memory was leveraged by the non-Brahmin intellectuals of Mumbai, who identified as his descendants and through him claimed the kshatriya varna. While some Brahmins rebutted this identity, defining them as of the lower shudra varna, other Brahmins recognised the Marathas' utility to the Indian independence movement, and endorsed this kshatriya legacy and the significance of Shivaji.[209]

Post independence

In modern times, Shivaji is considered as a national hero in India,[210][211][212][213] especially in the state of Maharashtra, where he remains an important figure in the state's history. Stories of his life form an integral part of the upbringing and identity of the Marathi people.[214]

Political parties

In 1966, the Shiv Sena (lit. 'Army of Shivaji') political party was formed to promote the interests of Marathi-speaking people in the face of migration to Maharashtra from other parts of India, and the accompanying loss of power of locals. His image adorns literature, propaganda, and icons of the party.[215]

Shivaji is seen as a hero by regional political parties and also by the Maratha-caste-dominated Indian National Congress and the Nationalist Congress Party.[216]

In the late 20th century, Babasaheb Purandare became one of the most significant authors in portraying Shivaji in his writings, leading him to be declared in 1964 as the Shiv-Shahir (lit. 'Bard of Shivaji').[217][218] However, Purandare, a Brahmin, was also accused of overstating the influence of Brahmin gurus on Shivaji,[216] and his Maharashtra Bhushan award ceremony in 2015 was protested by those claiming he had defamed Shivaji.[219]

In 1993, the Illustrated Weekly published an article suggesting that Shivaji was not opposed to Muslims per se, and that his style of governance was influenced by that of the Mughal Empire. Congress Party members called for legal actions against the publisher and writer, Marathi newspapers accused them of "imperial prejudice", and Shiv Sena called for the writer's public flogging. Maharashtra brought legal action against the publisher under regulations prohibiting enmity between religious and cultural groups, but a High Court found that the Illustrated Weekly had operated within the bounds of freedom of expression.[220][221]

In 2003, the American academic James W. Laine published his book Shivaji: Hindu King in Islamic India to, what Ananya Vajpeyi terms, a regime of "cultural policing by militant Marathas".[222][223] As a result of this publication, the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, in Pune, where Laine had done research, was attacked by the Sambhaji Brigade.[224][225] Laine was even threatened with arrest,[222] and the book was banned in Maharashtra in January 2004. The ban was lifted by the Bombay High Court in 2007, and in July 2010 the Supreme Court of India upheld the lifting of the ban.[226] This lifting was followed by public demonstrations against the author and the decision of the Supreme Court.[227][228]

Commemorations

Shivaji's statues and monuments are found almost in every town and city in Maharashtra, as well as in different places across India.[229][230][231]

The headquarters in Mumbai of the Western Railway zone, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was renamed Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus in 1996.[232][233] The busiest airport in Mumbai is named Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport.[234] In 2022, the Indian prime minister unveiled the new ensign of the Indian Navy, which was inspired by the seal of Shivaji.[235]

Other commemorations include the Indian Navy's INS Shivaji station[236] and numerous postage stamps.[237] In Maharashtra, there has been a long tradition of children building replica forts with toy soldiers and other figures during the festival of Diwali, in memory of Shivaji.[238][239]

A proposal to build a giant memorial called Shiv Smarak was approved in 2016; the memorial is to be located near Mumbai on a small island in the Arabian Sea. It will be 210 metres (690 ft) tall, which will make it the world's tallest statue when completed.[240] As of August 2021, the project has been stalled since January 2019, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Only the bathymetry survey has been completed, while the geotechnical survey was underway. Consequently, the state public works department proposed extending the completion date by a year, from 18 October 2021 to 18 October 2022.[241]

Sources

Notes

- ^ Based on multiple committees of historians and experts, the Government of Maharashtra accepts 19 February 1630 as his birthdate. This Julian calendar date of that period (1 March 1630 of today's Gregorian calendar) corresponds[17] to the Hindu calendar birth date from contemporary records.[18][19][20] Other suggested dates include 6 April 1627 or dates near this day.[21][22]

- ^ A decade earlier, Afzal Khan, in a parallel situation, had arrested a Hindu general during a truce ceremony.[52]

- ^ Jadunath Sarkar after weighing all recorded evidence in this behalf, has settled the point "that Afzal Khan struck the first blow" and that "Shivaji committed.... a preventive murder. It was a case of a diamond cut diamond." The conflict between Shivaji and Bijapur was essentially political in nature, and not communal.[54]

- ^ As per Stewart Gordon, there is no proof for this, and Shivaji probably bribed the guards. But other Maratha Historians including A. R. Kulkarni and G. B. Mehendale disagree with Gordon. Jadunath Sarkar probed more deeply into this and put forth a large volume of evidence from Rajasthani letters and Persian Akhbars. With the help of this new material, Sarkar presented a graphic account of Shivajï's visit to Aurangzeb at Agra and his escape. Kulkarni agrees with Sarkar.[93]

- ^ Most of the great Maratha Jahagirdar families in the service of Adilshahi strongly opposed Shivaji in his early years. These included families such as the Ghadge, More, Mohite, Ghorpade, Shirke, and Nimbalkar.[106]

- ^ Varna is sometimes also termed Varnashrama Dharma

- ^ As for the cause of his death, the Bombay Council's letter dated 28 April 1680 says: "We have certain news that Shivaji Rajah is dead. It is now 23 days since he deceased, it is said of a bloody flux, being sick 12 days." A contemporaneous Portuguese document states that Shivaji died of anthrax. However, none of these sources provides sufficient details to draw a definite conclusion. The Sabhasad Chronicle states that the King died of fever, while some versions of the A.K. Chronicle state that he died of "navjvar" (possibly typhoid).[144]

- ^ Shivaji was not attempting to create a universal Hindu rule. Over and over, he espoused tolerance and syncretism. He even called on Aurangzeb to act like Akbar in according respect to Hindu beliefs and places. Shivaji had no difficulty in allying with the Muslim states which surrounded him – Bijapur, Golconda, and the Mughals – even against Hindu powers, such as the nayaks of the Karnatic. Further, he did not ally with other Hindu powers, such as the Rajputs, rebelling against the Mughals.[170]

References

- ^ a b c Sardesai 1957, p. 222.

- ^ a b c Satish Chandra (1982). Medieval India: Society, the Jagirdari Crisis, and the Village. Macmillan. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-333-90396-4.

- ^ Gordon 2007, p. 84. sfn error: multiple targets (7×): CITEREFGordon2007 (help)

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley A. (2009). A New History of India. Oxford University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-19-533756-3.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 260.

- ^ James Laine (1996). Anne Feldhaus (ed.). Images of women in Maharashtrian literature and religion. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-7914-2837-5.

- ^ Dates are given according to the Julian calendar, see Mohan Apte, Porag Mahajani, M. N. Vahia. Possible errors in historical dates: Error in correction from Julian to Gregorian Calendars.

- ^ a b c d Robb 2011, pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b Govind Ranade, Mahadev (1900). Rise of the Maratha Power. India: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting.

- ^ a b c Pollock, Sheldon (2011). Forms of Knowledge in Early Modern Asia: Explorations in the Intellectual History of India and Tibet, 1500–1800. Duke University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8223-4904-4.

- ^ a b Sarkar, Jadunath (1920). Shivaji and his times. University of California Libraries. London, New York, Longmans, Green and co. pp. 20–30, 43, 437, 158, 163.

- ^ Deshpande 2015.

- ^ Scammell, G. (1992). European Exiles, Renegades and Outlaws and the Maritime Economy of Asia c. 1500–1750. Modern Asian Studies, 26(4), 641–661. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00010003, [1]

- ^ a b Wolpert 1962, pp. 79–81.

- ^ Biswas, Debajyoti; Ryan, John Charles (2021). Nationalism in India: Texts and Contexts. Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-00-045282-2.

- ^ Sengar, Bina; McMillin, Laurie Hovell (2019). Spaces and Places in Western India: Formations and Delineations. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-69155-9.

- ^ Apte, Mohan; Mahajani, Parag; Vahia, M. N. (January 2003). "Possible errors in historical dates" (PDF). Current Science. 84 (1): 21.

- ^ Kulkarni, A. R. (2007). Jedhe Shakavali Kareena. Diamond Publications. p. 7. ISBN 978-81-89959-35-7.

- ^ Kavindra Parmanand Nevaskar (1927). Shri Shivbharat. Sadashiv Mahadev Divekar. p. 51.

- ^ D.V Apte and M.R. Paranjpe (1927). Birth-Date of Shivaji. The Maharashtra Publishing House. pp. 6–17.

- ^ Siba Pada Sen (1973). Historians and historiography in modern India. Institute of Historical Studies. p. 106. ISBN 978-81-208-0900-0.

- ^ N. Jayapalan (2001). History of India. Atlantic Publishers & Distri. p. 211. ISBN 978-81-7156-928-1.

- ^ Sailendra Sen (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 196–199. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- ^ "Public Holidays" (PDF). maharashtra.gov.in. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 19.

- ^ Laine, James W. (2003). Shivaji: Hindu King in Islamic India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-972643-1.

- ^ a b V. B. Kulkarni (1963). Shivaji: The Portrait of a Patriot. Orient Longman.

- ^ a b Richard M. Eaton (2005). A Social History of the Deccan, 1300–1761: Eight Indian Lives. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 128–221. ISBN 978-0-521-25484-7.

- ^ Arun Metha (2004). History of medieval India. ABD Publishers. p. 278. ISBN 978-81-85771-95-3.

- ^ Kalyani Devaki Menon (2011). Everyday Nationalism: Women of the Hindu Right in India. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-0-8122-0279-3.

- ^ Marathi book Shivkaal (Times of Shivaji) by Dr V G Khobrekar, Publisher: Maharashtra State Board for Literature and Culture, 1st. ed. 2006. Chapter 1

- ^ Salma Ahmed Farooqui (2011). A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: From Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century. Dorling Kindersley India. pp. 314–. ISBN 978-81-317-3202-1.

- ^ Subrahmanyam 2002, pp. 33–35.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (2007). The Marathas 1600–1818. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03316-9.

- ^ Sarkar, Jadunath (1952). Shivaji and his times (5th ed.). Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan Private Limited. p. 19. ISBN 978-8125040262.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (2007). The Marathas 1600–1818. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03316-9.

- ^ a b Mahajan, V. D. (2000). India since 1526 (17th ed., rev. & enl ed.). New Delhi: S. Chand. p. 198. ISBN 81-219-1145-1. OCLC 956763986.

- ^ Gordon, The Marathas 1993, p. 61.

- ^ Kulkarni, A.R., 1990. Maratha Policy Towards the Adil Shahi Kingdom. Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute, 49, pp. 221–226.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Eaton, Richard M. (2019). India in the Persianate Age: 1000–1765. Penguin UK. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-14-196655-7.

- ^ a b Stewart Gordon (2007). The Marathas 1600–1818. Cambridge University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-521-03316-9.

- ^ Gordon, S. (1993). The Marathas 1600–1818 (The New Cambridge History of India). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521268837 p. 69, [2]

- ^ Gordon, The Marathas 1993, p. 66.

- ^ John F. Richards (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 208–. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- ^ Eaton, The Sufis of Bijapur 2015, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik (2012). Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-139-57684-0.

- ^ Abraham Eraly (2000). Last Spring: The Lives and Times of Great Mughals. Penguin Books Limited. p. 550. ISBN 978-93-5118-128-6.

- ^ Kaushik Roy (2012). Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press. pp. 202–. ISBN 978-1-139-57684-0.

- ^ Gier, The Origins of Religious Violence 2014, p. 17.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 70.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (2007). The Marathas 1600–1818. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-521-03316-9.

- ^ Haig & Burn, The Mughal Period 1960, p. 22.

- ^ Kulkarni, A. R. (2008). The Marathas. Diamond Publications. ISBN 978-81-8483-073-6.

- ^ Haig & Burn, The Mughal Period 1960.

- ^ a b Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 75.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 78.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 266.

- ^ Ali, Shanti Sadiq (1996). The African Dispersal in the Deccan: From Medieval to Modern Times. Orient Blackswan. p. 124. ISBN 978-81-250-0485-1.

- ^ Farooqui, A Comprehensive History of Medieval India 2011, p. 283.

- ^ Sardesai 1957.

- ^ a b Shripad Dattatraya Kulkarni (1992). The Struggle for Hindu supremacy. Shri Bhagavan Vedavyasa Itihasa Samshodhana Mandira (Bhishma). p. 90. ISBN 978-81-900113-5-8.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, pp. 55–56.

- ^ S.R. Sharma (1999). Mughal empire in India: a systematic study including source material, Volume 2. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 59. ISBN 978-81-7156-818-5.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 57.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 60.

- ^ Indian Historical Records Commission: Proceedings of Meetings. Superintendent Government Printing, India. 1929. p. 44.

- ^ Aanand Aadeesh (2011). Shivaji the Great Liberator. Prabhat Prakashan. p. 69. ISBN 978-81-8430-102-1.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (2007). The Marathas 1600–1818. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-521-03316-9.

- ^ Mahmud, Sayyid Fayyaz; Mahmud, S. F. (1988). A Concise History of Indo-Pakistan. Oxford University Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-19-577385-9.

- ^ Richards, John F. (1993). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- ^ Mehta 2009, p. 543.

- ^ Mehta 2005, p. 491.

- ^ Shejwalkar, T.S. (1942). Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute. Vol. 4. Vice Chancellor, Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute (Deemed University), Pune. pp. 135–146. JSTOR 42929309. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "Mega event to mark Karnataka port town Basrur's liberation from Portuguese by Shivaji". New Indian Express. 15 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Gordon, Stewart (1993). The Marathas 1600–1818, Part 2, Volume 4. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1, 3–4, 50–55, 59, 71–75, 114, 115–125, 133, 138–139. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521268837. ISBN 9780521268837.

- ^ Haig & Burn, The Mughal Period 1960, p. 258.

- ^ Sarkar, History of Aurangzib 1920, p. 77.

- ^ Gordon, The Marathas 1993, p. 74.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (1994). Marathas, Marauders, and State Formation in Eighteenth-century India. Oxford University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-19-563386-3.

- ^ Gordon, The Marathas 1993, p. 78.

- ^ Jain, Meenakshi (2011). The India They Saw (Vol. 3). Prabhat Prakashan. pp. 299, 300. ISBN 978-81-8430-108-3.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (2007). The Marathas 1600–1818. Cambridge University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-521-03316-9.

- ^ Sarkar, Jadunath (1994). A History of Jaipur: c. 1503–1938. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-0333-5.

- ^ Mehta, Jl. Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 547. ISBN 978-81-207-1015-3.

- ^ Datta, Nonica (2003). Indian History: Ancient and medieval. Encyclopaedia Britannica (India) and Popular Prakashan, Mumbai. p. 263. ISBN 978-81-7991-067-2.

- ^ Patel, Sachi K. (2021). Politics and Religion in Eighteenth-Century India: Jaisingh II and the Rise of Public Theology in Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavism. Routledge. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-00-045142-9.

- ^ Sabharwal, Gopa (2000). The Indian Millennium, AD 1000–2000. Penguin Books. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-14-029521-4.

- ^ Mahajan, V. D. (2007). History of Medieval India. S. Chand Publishing. p. 190. ISBN 978-81-219-0364-6.

- ^ Kulkarni, A. R. (2008). The Marathas. Diamond Publications. p. 34. ISBN 978-81-8483-073-6.

- ^ Gandhi, Rajmohan (2000). Revenge and Reconciliation: Understanding South Asian History. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-81-8475-318-9.

- ^ SarDesai, D. R. (2018). India: The Definitive History. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-97950-7.

- ^ Kulkarni, A. R. (1996). Marathas And The Maratha Country: Vol. I: Medieval Maharashtra: Vol. II: Medieval Maratha Country: Vol. III: The Marathas (1600–1648) (3 Vols.). Books & Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-81-85016-51-1.

- ^ Sarkar, History of Aurangzib 1920, p. 98.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 185.

- ^ Gordon, The Marathas 1993, p. 231.

- ^ Murlidhar Balkrishna Deopujari (1973). Shivaji and the Maratha Art of War. Vidarbha Samshodhan Mandal. p. 138.

- ^ Eraly, Emperors of the Peacock Throne 2000, p. 460.

- ^ Eraly, Emperors of the Peacock Throne 2000, p. 461.

- ^ Sarkar, History of Aurangzib 1920, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Sarkar, History of Aurangzib 1920, p. 175.

- ^ Sarkar, History of Aurangzib 1920, p. 189.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 393.

- ^ Sarkar, History of Aurangzib 1920, pp. 230–233.

- ^ Malavika Vartak (May 1999). "Shivaji Maharaj: Growth of a Symbol". Economic and Political Weekly. 34 (19): 1126–1134. JSTOR 4407933.

- ^ Daniel Jasper 2003, p. 215.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (1993). The New Cambridge history of India. II, The Indian States and the transition to colonialism. 4, The Marathas, 1600–1818. Cambridge: Cambridge university press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-521-26883-7. OCLC 489626023.

- ^ Rajmohan Gandhi (1999). Revenge and Reconciliation. Penguin Books India. pp. 110–. ISBN 978-0-14-029045-5.

On the ground that Shivaji was merely a Maratha and not a kshatriya by caste, Maharashtra's Brahmins had refused to conduct a sacred coronation.

- ^ Gordon, The Marathas 1993, p. 87-88.

- ^ B. S. Baviskar; D. W. Attwood (2013). Inside-Outside: Two Views of Social Change in Rural India. Sage Publications. pp. 395–. ISBN 978-81-321-1865-7.

- ^ Gordon, The Marathas 1993, p. 88.

- ^ Cashman, The Myth of the Lokamanya 1975, p. 7.

- ^ Farooqui, A Comprehensive History of Medieval India 2011, p. 321.

- ^ Oliver Godsmark (2018). Citizenship, Community and Democracy in India: From Bombay to Maharashtra, c. 1930–1960. Taylor & Francis. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-1-351-18821-0.

- ^ Varma, Supriya; Saberwal, Satish (2005). Traditions in Motion: Religion and Society in History. Oxford University Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-19-566915-2.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 244.

- ^ a b Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 245.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 252.

- ^ Manu S Pillai (2018). Rebel Sultans: The Deccan from Khilji to Shivaji. Juggernaut Books. p. xvi. ISBN 978-93-86228-73-4.

- ^ Barua, Pradeep (2005). The State at War in South Asia. University of Nebraska Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8032-1344-9.

- ^ Mallavarapu Venkata Siva Prasada Rau (Andhra Pradesh Archives) (1980). Archival organization and records management in the state of Andhra Pradesh, India. Published under the authority of the Govt. of Andhra Pradesh by the Director of State Archives (Andhra Pradesh State Archives). p. 393.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920.

- ^ Yuva Bharati (Volume 1 ed.). Vivekananda Rock Memorial Committee. 1974. p. 13.

About 50,000 people witnessed the coronation ceremony and arrangements were made for their boarding and lodging.

- ^ H. S. Sardesai (2002). Shivaji, the Great Maratha. Cosmo Publications. p. 431. ISBN 978-81-7755-286-7.

- ^ Narayan H. Kulkarnee (1975). Chhatrapati Shivaji, Architect of Freedom: An Anthology. Chhatrapati Shivaji Smarak Samiti.

- ^ U. B. Singh (1998). Administrative System in India: Vedic Age to 1947. APH Publishing. p. 92. ISBN 978-81-7024-928-3.

- ^ Tej Ram Sharma (1978). Personal and Geographical Names in the Gupta Inscriptions. Concept Publishing Company. p. 72. GGKEY:RYD56P78DL9.

- ^ Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava (1964). The History of India, 1000 A.D.–1707 A.D. Shiva Lal Agarwala. p. 701.

Shivaji was obliged to undergo a second coronation ceremony on 4th October 1674, on the suggestion of a well-known Tantrik priest, named Nishchal Puri Goswami, who said that Gaga Bhatta had performed the ceremony at an inauspicious hour and neglected to propitiate the spirits adored in the Tantra. That was why, he said, the queen mother Jija Bai had died within twelve days of the ceremony and similar other mishaps had occurred.

- ^ Indian Institute of Public Administration. Maharashtra Regional Branch (1975). Shivaji and swarajya. Orient Longman. p. 61.

one to establish that Shivaji belonged to the Kshatriya clan and that he could be crowned a Chhatrapati and the other to show that he was not entitled to the Vedic form of recitations at the time of the coronation

- ^ Shripad Rama Sharma (1951). The Making of Modern India: From A.D. 1526 to the Present Day. Orient Longmans. p. 223.

The coronation was performed at first according to the Vedic rites, then according to the Tantric. Shivaji was anxious to satisfy all sections of his subjects. There was some doubt about his Kshatriya origin (see note at the end of this chapter). This was of more than academic interest to his contemporaries, especially Brahmans [Brahmins]. Traditionally considered the highest caste in the Hindu social hierarchy. the Brahmans would submit to Shivaji, and officiate at his coronation, only if his

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 17.

- ^ Maharashtra (India) (1967). Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Maratha period. Directorate of Government Printing, Stationery and Publications, Maharashtra State. p. 147.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 258.

- ^ Gijs Kruijtzer (2009). Xenophobia in Seventeenth-Century India. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 153–190. ISBN 978-90-8728-068-0.

- ^ Kulkarni, A. R. (1990). "Maratha Policy Towards the Adil Shahi Kingdom". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 49: 221–226. JSTOR 42930290.

- ^ Haig & Burn, The Mughal Period 1960, p. 276.

- ^ Everett Jenkins Jr. (2010). The Muslim Diaspora (Volume 2, 1500–1799): A Comprehensive Chronology of the Spread of Islam in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas. McFarland. pp. 201–. ISBN 978-1-4766-0889-1.

- ^ Haig & Burn, The Mughal Period 1960, p. 290.

- ^ Sardesai 1957, p. 251.

- ^ Maya Jayapal (1997). Bangalore: the story of a city. Eastwest Books (Madras). p. 20. ISBN 978-81-86852-09-5.

Shivaji's and Ekoji's armies met in battle on 26 November 1677, and Ekoji was defeated. By the treaty he signed, Bangalore and the adjoining areas were given to Shivaji, who then made them over to Ekoji's wife Deepabai to be held by her, with the proviso that Ekoji had to ensure that Shahaji's Memorial was well tended.

- ^ a b Mehta 2005, p. 47.

- ^ Haig & Burn, The Mughal Period 1960, p. 278.

- ^ Mehendale 2011, p. 1147.

- ^ Pissurlencar, Pandurang Sakharam. Portuguese-Mahratta Relations. Maharashtra State Board for Literature and Culture. p. 61.

- ^ a b Mehendale, Gajanan Bhaskar (2011). Shivaji his life and times. India: Param Mitra Publications. p. 1147. ISBN 978-93-80875-17-0. OCLC 801376912.

- ^ a b c Mahajan, V. D. (2000). India since 1526 (17th ed., rev. & enl ed.). New Delhi: S. Chand. p. 203. ISBN 81-219-1145-1. OCLC 956763986.

- ^ Truschke 2017, p. 53.

- ^ Mehta 2005, p. 48.

- ^ Sunita Sharma, K̲h̲udā Bak̲h̲sh Oriyanṭal Pablik Lāʼibrerī (2004). Veil, sceptre, and quill: profiles of eminent women, 16th–18th centuries. Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Public Library. p. 139.

By June 1680 three months after Shivaji's death Rajaram was made a prisoner in the fort of Raigad, along with his mother Soyra Bai and his wife Janki Bai. Soyra Bai was put to death on charge of conspiracy.

- ^ White, Matthew (2011). Atrocitology: Humanity's 100 Deadliest Achievements. Canongate Books. ISBN 978-0-85786-125-2.

- ^ Eraly, Abraham (2007). Emperors Of The Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Moghuls. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-93-5118-093-7.

- ^ John Clark Marshman (2010). History of India from the Earliest Period to the Close of the East India Company's Government. Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-108-02104-3.

- ^ Pearson, Shivaji and Mughal decline 1976, p. 226.

- ^ Potter, George Richard (1967). The New Cambridge Modern History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 549, 563.

- ^ a b Gordon, Stewart (1993). The Marathas 1600–1818, Part 2, Volume 4. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1, 3–4, 50–55, 59, 71–75, 114, 115–125, 133, 138–139. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521268837. ISBN 9780521268837.

- ^ Sailendra N. Sen (1994). Anglo-Maratha relations during the administration of Warren Hastings 1772–1785. Popular Prakashan. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-81-7154-578-0.

- ^ Nehru, Jawaharlal (1 February 2008). Discovery of India. Penguin Random House India Private Limited. pp. 272, 276. ISBN 978-93-85990-05-2.

- ^ Jeremy Black (2006). A Military History of Britain: from 1775 to the Present. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-99039-8.

- ^ Percival Spear (1990) [First published 1965]. A History of India. Vol. 2. Penguin Books. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-14-013836-8.

- ^ a b Ashta Pradhan at the Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Kulkarni, A. R. (2008). The Marathas. Diamond Publications. ISBN 978-81-8483-073-6.

- ^ Pollock, Sheldon (2011). Forms of Knowledge in Early Modern Asia: Explorations in the Intellectual History of India and Tibet, 1500–1800. Duke University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8223-4904-4.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 421.

- ^ Gier, Nicholas F. (2014). The Origins of Religious Violence: An Asian Perspective. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-9223-8.

- ^ Sardesai 1957, p. 250.

- ^ American Oriental Society (1963). Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. p. 476. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ Gijs Kruijtzer, Xenophobia in Seventeenth-Century India (Leiden University Press, 2009).

- ^ Panduronga S. S. Pissurlencar (1975). The Portuguese and the Marathas: Translation of Articles of the Late Dr. Pandurang S. Pissurlenkar's Portugueses E Maratas in Portuguese Language. State Board for Literature and Culture, Government of Maharashtra. p. 152.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (2007). The Marathas 1600–1818. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03316-9.

- ^ Kulkarni, A. R. (July 2008). Medieval Maratha Country. Diamond Publications. ISBN 978-81-8483-072-9.

- ^ Eraly, Abraham (2007). Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Moghuls. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-93-5118-093-7.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik (3 June 2015). Warfare in Pre-British India – 1500BCE to 1740CE. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-58691-3.

- ^ Barua, Pradeep (1 January 2005). The State at War in South Asia. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1344-9.

- ^ Davis, Paul (25 July 2013). Masters of the Battlefield: Great Commanders from the Classical Age to the Napoleonic Era. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-534235-2.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (1 February 2007). The Marathas 1600–1818. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03316-9.

- ^ Kantak, M. R. (1993). The First Anglo-Maratha War, 1774–1783: A Military Study of Major Battles. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-7154-696-1.

- ^ Bhave, Y. G. (2000). From the Death of Shivaji to the Death of Aurangzeb: The Critical Years. Northern Book Centre. p. 7. ISBN 978-81-7211-100-7.

- ^ Stanley A. Wolpert (1994). An Introduction to India. Penguin Books India. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-14-016870-9.

- ^ Hugh Tinker (1990). South Asia: A Short History. University of Hawaii Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8248-1287-4.

- ^ Kantak, M. R. (1993). The First Anglo-Maratha War, 1774–1783: A Military Study of Major Battles. Popular Prakashan. p. 9. ISBN 978-81-7154-696-1.

- ^ Abhang, C. J. (2014). UNPUBLISHED DOCUMENTS OF EAST INDIA COMPANY REGARDING DESTRUCTION OF FORTS IN JUNNER REGION. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 75, 448–454. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44158417

- ^ Pagadi 1983, p. 21.

- ^ M. S. Naravane (1 January 1995). Forts of Maharashtra. APH Publishing Corporation. p. 14. ISBN 978-81-7024-696-1.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 408.

- ^ Sarkar, History of Aurangzib 1920, p. 414.

- ^ Kaushik Roy (30 March 2011). War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740–1849. Taylor & Francis. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-1-136-79087-4.

- ^ a b Sarkar, History of Aurangzib 1920, p. 59.

- ^ Bhagamandala Seetharama Shastry (1981). Studies in Indo-Portuguese History. IBH Prakashana.

- ^ Kaushik Roy; Peter Lorge (17 December 2014). Chinese and Indian Warfare – From the Classical Age to 1870. Routledge. pp. 183–. ISBN 978-1-317-58710-1.

- ^ "New Naval Ensign: The naval prowess of Chhatrapati Shivaji that has always inspired the Indian Navy - Optimize IAS". 3 September 2022.

- ^ Raj Narain Misra (1986). Indian Ocean and India's Security. Mittal Publications. pp. 13–. GGKEY:CCJCT3CW16S.

- ^ Sarkar, Shivaji and His Times 1920, p. 74.

- ^ Sen, Surendra (1928). Foreign Biographies of Shivaji. Vol. II. London, K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & co. ltd. p. xiii.

- ^ Krishna, Bal (1940). Shivaji The Great. The Arya Book Depot Kolhapur. pp. 11–12.

- ^ Surendra Nath Sen (1977). Foreign Biographies of Shivaji. K. P. Bagchi. pp. 14, 139.

- ^ Truschke 2017, p. 54.

- ^ A History of Marathas by Grant Duff Vol. 1.

- ^ Uma Chakravarti (2014). Rewriting History: The Life and Times of Pandita Ramabai. Zubaan. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-93-83074-63-1.

- ^ Biswamoy Pati (2011). Bal Gangadhar Tilak: Popular Readings. Primus Books. p. 101. ISBN 978-93-80607-18-4.

- ^ Cashman, The Myth of the Lokamanya 1975, p. 107.

- ^ Indo-British Review. Indo-British Historical Society. p. 75.

- ^ McLain, Karline (2009). India's Immortal Comic Books: Gods, Kings, and Other Heroes. Indiana University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-253-22052-3.

- ^ Prachi Deshpande (2007). Creative Pasts: Historical Memory and Identity in Western India, 1700–1960. Columbia University Press. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-0-231-12486-7.

Shivaji and His Times, was widely regarded as the authoritative follow-up to Grant Duff. An erudite, painstaking Rankean scholar, Sarkar was also able to access a wide variety of sources through his mastery of Persian, Marathi, and Arabic, but as explained in the last chapter, he earned considerable hostility from the Poona [Pune] school for his sharp criticism of the "chauvinism" he saw in Marathi historians' appraisals of the Marathas

- ^ C. A. Bayly (2011). Recovering Liberties: Indian Thought in the Age of Liberalism and Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 282–. ISBN 978-1-139-50518-5.

- ^ Dennis Kincaid (1937). The Grand Rebel.

- ^ Girja Kumar (1997). The Book on Trial: Fundamentalism and Censorship in India. Har-Anand Publications. p. 431. ISBN 978-81-241-0525-2.

- ^ Bipan Chandra; Mridula Mukherjee; Aditya Mukherjee; K N Panikkar; Sucheta Mahajan (2016). India's Struggle for Independence. Penguin Random House India Private Limited. pp. 107–. ISBN 978-81-8475-183-3.