Stirchley, Birmingham

| Stirchley | |

|---|---|

View of Pershore Road looking north, with the British Oak public house to the left | |

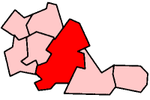

Location within the West Midlands | |

| OS grid reference | SP054812 |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BIRMINGHAM |

| Postcode district | B30 |

| Dialling code | 0121 |

| Police | West Midlands |

| Fire | West Midlands |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

Stirchley is a suburb in south-west Birmingham, England.[1] The name likely refers to a pasture for cattle. The settlement dates back to at least 1658. Prehistoric evidence, Roman roads, and Anglo-Saxon charters contribute to its history. The Worcester and Birmingham Canal and the railways brought industry to the area. Stirchley's development is also linked to industries like screw-making and rubber manufacturing. Originally part of Worcestershire, Stirchley underwent administrative changes in 1911. Residential developments were established alongside the long-standing Victorian terracing which is associated with the suburb.

The River Rea, which flows through the area and once powered mills at Lifford, Hazelwell, Dogpool and Moor Green, is now a walking and cycle route. The restored former Stirchley Baths community hub opened in 2016.[2]

Political[edit]

In 2018, Stirchley separated from the Bournville Ward to become a ward in its own right. It is represented by Councillor Mary Locke (Lab). Stirchley is in the Parliamentary Constituency of Selly Oak represented by Steve McCabe (Lab). Until the Local Provisional Order Bill came into effect on 9 November 1911,[3] the area was administered by the King’s Norton and Northfield Urban District Council in the East Worcestershire (UK Parliament constituency) represented by Austen Chamberlain. The event, known as the Greater Birmingham Act,[4] required the ancient county boundaries of Staffordshire, Worcestershire and Warwickshire to be changed. The former county boundary was the Bourn Brook which separates Edgbaston (Warwickshire), from Selly Oak (Worcestershire). Slightly more than 22,000 acres of Worcestershire was transferred to Warwickshire in the extension of the administrative area of Birmingham, and this has grown further with the creation of New Frankley.[5] Nearly 50% of modern Birmingham was formerly in Worcestershire or Staffordshire. The Evolution of Worcestershire county boundaries since 1844 is complex as a number of enclaves and exclaves were adjusted. Documentary references need to be researched under the county of origin. An editorial note in the VCH Warwickshire Volume 7 Birmingham refers to the special difficulties created by the change of the county boundaries and states that: "Accounts of the ancient parishes of King’s Norton, Northfield, and Yardley, and the parish of Quinton (in the ancient parish of Halesowen), now within the boundaries of the city, are contained in Volume III of the History of Worcestershire."[6]

Toponymy[edit]

Lock considers the reference to Stercan Lei in the 730 Cartularium Saxonicum applies to Stirchley. A stirk or Styrk is Old English for heifer, and therefore the name signifies the clearing or pasture for cattle.[7] This has been adopted as the meaning of Stirchley in Shropshire.

The earliest known reference of a settlement at Stirchley is a deed dated 6 May 1658, where it is described as an "Indenture between Katherine Compton and Daniel Greves and others concerning a tenement and lands at Stretley Streete in the Parish of King’s Norton".[8] In his research of the history of the building called Selly Manor,[9] Demidowicz identified it to be a Yeoman’s house before becoming cottages called the Rookery. He also identified the site of the medieval settlement of Barnbrook’s End. This is connected to Barnbrook Hall, frequently referred to as Bournbrook Hall, which is confusing because of another property of the same name in Bournbrook. Demidowicz accessed a 1602 map that showed that Stretley Brook was the boundary between the ancient parishes of Northfield and King’s Norton.[10] The brook was later known as Gallows Brook, Griffins Brook, and, after the Cadbury Brothers established their Cocoa Company it became ‘The Bourn’. It is likely that Gallows Brook was the former name of Wood Brook, which flows from Northfield, as in 1783 Thomas Wardle, was sentenced to be executed and his body hung in Chains on the further Part of Bromsgrove Lickey, near Northfield. Three others also received death sentences.[11]

In a map published in 1789, James Sheriff names the place as Stutley, while one of 1796 names Sturchley.[7] However, Chinn suggests that an 18th-century map maker mis-read the ‘ee’ and replaced it with a ‘u’.[12]

In 1863, Strutley Street branch national school was opened to accommodate 132 pupils. It replaced a former school suggesting there was an established population in the area before this date.[13] Hazelwell Street was shown as Strutley Street on the plans for the sale of land to be developed in conjunction with straightening the Pershore Road.

History[edit]

Prehistoric[edit]

Evidence of human activity during the Bronze Age is provided by the presence of mounds of heat-shattered and fissured pebbles in charcoal referred to as ‘burnt mounds’. Such mounds have been identified along the River Rea in Wychall Lane, at Ten Acres, and at Moseley Bog. No settlement associated with this period has been found.[14] Prehistoric settlements or farmsteads are difficult to find in built-up areas, however, there is a possibility of occupation at Cotteridge. Chinn suggests that the name Cotteridge means Cotta’s Ridge, and there is a clear ridge running up from Breedon Hill.[15] The Tithe Map records a feature of Near and Far Motts, now beneath the housing development at Foxes Meadow[16] suggesting the possibility of an ancient Celtic settlement, hill-fort, or look-out site at the top of the ridge which runs through Northfield to Dudley. Alternatively, it may be the medieval Vill of Northfield’s Sub-Manor of Middleton[17] as the site was possibly included on the auctioneer's plan for the sale of the Estate of Middleton Hall.[18]

Hutton commented that "In the parish of King’s Norton, four miles [6 kilometres] south west of Birmingham is ‘The Moats’, upon which long resided the ancient family of Field. The numerous buildings, which almost formed a village, are totally erased and barley grows where the beer was drank."[19] This location would have provided an excellent panoramic view of the south of the Birmingham Plateau. The ancient pre-urban landscape was not dissimilar to that of Bredon Hill near Evesham. Both ‘Bre’ (Celtic) and ‘don’ (Old English) mean hill.[20] Demidowicz has identified that the Rea was formerly called the Cole, a derivative of the Welsh Celtic word ‘colle’ meaning Hazel. In a map of the locations mentioned in an Anglo-Saxon Charter the site where the Rea crosses Dogpool Lane was referred to in 1495 as Collebrugge and in 1496 as Colebruge.[21]

Roman[edit]

The Roman Road Icknield Street, or Ryknield Street, connected Alcester with Metchley Fort. Evidence of this road at Walkers Heath Road, Broadmeadow Lane, Lifford Lane, and Stirchley Street suggests a route along a terrace that avoided medieval King’s Norton Green and Cotteridge.[16] There is a reference to Selly Cross which may be where Icknield Street converged with the Upper Saltway now the Bristol Road (A38). The Roman Road may have followed a more ancient packhorse route with salt as the most obvious commodity to be transported. From Metchley Fort the road went north through the Streetly Valley in Sutton Park where there is a watercourse called the Bourne Brook[22] Continuing northwards, Icknield Street crossed Watling Street (A5) near Letocetum, the Roman site at Wall, close to Hammerwich where the Staffordshire Hoard was found.[23] Barrow suggests that another road, the Hadyn Way ran in a southerly direction from the Ryknield Street near Bournbrook through Stirchley Street and Alauna (Alcester) to join the Fosse Way near Bourton-on-the-Water.[24] Peter Leather indicates that Dogpool Lane may have been a minor Roman route from the Alcester Road to Metchley Fort via Warwards Lane and Selly Park Recreation Ground where a significant archaeological survey was undertaken.[25]

Until recently, the place name of Stirchley was accompanied by ‘Street’. Gelling suggests that major place-names like Strete or Streetly refer to the position of the settlement on or close to one of the main roads of Roman Britain.[26] It is possible that the name Street is a corruption of the OE Stroet which has been interpreted as a "Roman road, a paved road, an urban road, a street".[27] The 1838 Tithe Map for King’s Norton Parish in the County of Worcestershire identifies the place, rather than the road name, as Stirchley Street.[28] Other Place names associated with Roman occupation are Street Farm Northfield where the road from Wootton Wawen met the Bromsgrove Road, and Moor Street Bartley Green.

Anglo-Saxon[edit]

Stirchley was in the ancient parish of King’s Norton. King’s Norton had two Anglo-Saxon boundary charters: Hellerelege (AD 699-709) which was a grant by Offa, King of Mercia, and Cofton (AD 849) in which Bishop Ealhun of Worcester has leased the 20 hide estate to King Berhtwulf. Plotting these boundaries has proved difficult as many of the names have changed.[29] The boundaries of King’s Norton parish and the manor were coterminous and stretched from Balsall Heath in the north to Wythall in the south, from Rednal in the west to Solihull Lodge in the east. Beating the bounds took four days to complete. The population was scattered but small hamlets and later sub-manors were formed. For administration purposes the parish was divided into five yields or taxable divisions.[30] Lea yield, which was probably focused on the area of Leys Farm in Stirchley, was consumed by the Moseley and Moundesley yields around the time of the Tithe Commutation Act of 1836 and is not shown with the Tithe Map and Apportionments.

Domesday Book indicates that Bromsgrove was a significant manor with eighteen outliers or berewicks.[31] Some these manors are now part of the Anglo-Saxon presence in Greater Birmingham: Moseley, King’s Norton, Lindsworth, Tessall, Rednal, Wychall, and possibly Lea. There are ongoing arguments as to the location of Lea. Monkhouse considered the reference to belong to the Stirchley area of Leys Farm while F and C Thorn identified it as Lea Green near Houndsfield and Wythwood. Leys Farm was not mentioned on the 1832 OS map although there is the possibility of a building on the site.[32] A considerable period of time has elapsed since those discussions and it seems valid that the debate should be resumed now that so much more information is available.

At the time of the Domesday survey in 1086, Birmingham was a manor in Warwickshire[33] with less than 3,000 acres whereas the current Birmingham Metropolitan Borough is closer to 66,219 acres (26,798 ha).[34] Birmingham developed in the hinterland of three counties – Warwickshire, Staffordshire, and Worcestershire and nearly 50% of modern Birmingham has Domesday Book manors that were formerly in either Staffordshire,[35] or Worcestershire,[36] As the city expanded the ancient Shire boundaries were changed in order that the area being administered came under one county authority – Warwickshire.[37] To establish the Saxon presence in the territory of modern Birmingham all the former Manors and Berewicks/Outliers mentioned in Domesday Book that are now within the boundaries of the City, need to be combined.[38] This is complicated by the fact that separate figures were not given for Harborne (Staffordshire), Yardley and King’s Norton (Worcestershire) which were all attached to manors outside the area. The Birmingham Plateau had about 26 Domesday Book manors, a population of close to 2,000, with seven mills, and three priests.

Other Worcestershire manors mentioned in Domesday Book are: Yardley; Selly Oak and its outlier Bartley Green; Northfield; Frankley (New Frankley); and Halesowen (Quinton).[39] Harborne (Staffordshire) was owned by the Bishop of Lichfield.[40] Selly Oak was leased to Wulfwin, who owned Birmingham as a freeman, by the Bishop of Lichfield. "Leases meant services to the bishop, and in this way he ensured the cultivated of the lands he retained in his own hands, as well as those which he let out, and had a large force ready at hand in case of war or tumult." These services could have been called upon during the raids by the Danes.[41] The nun-cupative (oral) will is a unique inclusion and suggests that the Bishop had a particular reason for not wishing to lose the territory of Selly Oak which meets Stirchley north of the Bourn and west of the River Rea.

The Domesday Book manors of both King’s Norton and Selly Oak were in pre-Conquest Came Hundred which later became Halfshire Hundred. A Hundred was an administrative division of a Shire (County). Some Tithe maps field names near Moor Green called Big Hundred (3260), Little Hundred (3257), Upper Hundred (2759), Lower Hundred (2760), plus Hundreds Meadow (3261), hint that there was once a hundred meeting place there in Anglo-Saxon times. The site is near to the Dogpool Lane Bridge over the Rea, which might once have been a ford as the stream runs wide and shallow at that point. Such a spot was favoured for early meeting places.[42] Just west of the River Rea is the Selly Wick Estate. The ‘wick’ may be a loan from the Latin vicus, a civilian settlement associated with a Roman fort or it may belong to a variety of meanings including salt-working centre or a dairy farm.[43] This estate joins the Selly Hall Estate and as ‘sel’ or 'cel' may derive from the Anglo-Saxon for house, hall, or storage building[44] it is possible that an earlier structure may lie beneath what is now the Convent of the Sisters of Charity of St Paul the Apostle.[45] Near Selly Wick House and once part of the Selly Hall Estate[46] are the remains of a medieval moat and fishponds.[47]

Mills[edit]

Lifford Mill and pool lie on the south side of Tunnel Lane where it crosses the eastern of the two branches of the Rea at Lifford. It may have been the Dobbs Mill shown in the area in 1787–9. The pool and the reservoir below the mill were formed when the Worcester and Birmingham Canal was constructed in the early 19th century. In 1830 the mill was described as a ‘rolling mill of 15 horse power upon a never-failing stream. In 1841 Joseph Davies left it together with Harborne Mill to his son Samuel. In 1873 and 1890 it was occupied by india-rubber manufacturers. By 1900 it had become part of the works of J & E Sturge, chemical manufacturers. The mill building is now derelict, but both it and Lifford House form part of the premises of J & E Sturge, Ltd.[48]

Hazelwell Mill and pool lie on the east of the Rea immediately above Hazelwell Fordrough. The three water corn mills in Hazelwell manor in 1704 were probably at this mill, and the mill was similarly described when in the tenure of Thomas Hadley in 1733. Edward Jordan, who took over the mill from John White in 1756, was, like the Hadley’s, a gunsmith. The mill was, however, being used for corn milling, stones in the rye mill and the wheat mill being mentioned in the lease. The three water corn mills were again mentioned in 1776 and in 1787, but by the early 19th century the mill had been converted to metal working. In 1843 and 1863 it was in the tenure of William Deakin and Sons, sword-cutlers, gun-barrel and bayonet manufacturers, and in the 1870s of William Millward and Sons, sword-cutlers, gun and pistol-barrel makers. It was a gun-barrel works in 1886, but by the 1900s had become a rubber factory.[49]

Dogpool Mill with its pool lies to the west of the Rea just below the point where Griffin’s Brook joins the Rea. It was mentioned as Dog Poo’ Mill in 1800 and was a rolling mill in 1836. The tenant in 1843 was John Phipson and in 1863 Tomlinson and Co., tube- and wire-manufacturers. By 1875 the mill had been taken over by C Clifford and Sons, metal-rollers and tube-makers.[50]

Moor Green, or Farmons Mill and its pool, lay on the east of the Rea just above the point where Holders Lane reaches the river. The mill, called a blade mill, was already in existence when the Moore family acquired it from John Middlemore, together with the manor, in 1597. It was held by the Moore family until 1783 when it was sold by John Moore to James Taylor. The Serjeant family held the lease of the mill from Moore and Taylor between 1780 and 1841, and William Serjeant greatly improved the mill, then still a blade mill, between 1816 and 1841. In 1841 his widow surrendered the lease to James Taylor and the freehold was sold to Charles Umpage, metal-roller. William Betts and Co., metal-rollers, occupied the mill in the 1860s and 70s. It was still in use as a rolling mill in the 1880s but seems to have fallen into disuse shortly after, and only a part of the wheel channel still remains.[50]

Sherborne Mill, also known as the Kings Norton Paper Mill, was built by James Baldwin & Sons Ltd, paper makers of Birmingham, in the 1850s. The mill produced brown papers for wrapping, grocery papers, paper bags and gun wadding. The mill became an independent business in 1926 which was dissolved in 1967. The buildings were converted to hold the Patrick Collection of vintage cars. It is now called the Lakeside Centre and Lombard Rooms. An artificial pond, created to provide water for the paper-making process, still exists on site. James Baldwin was Mayor of Birmingham in 1853–54. The Baldwin family lived nearby at Breedon House, now the site of the Cotteridge school.[51]

Farms[edit]

Using the modern road names to identify the location: Lea House Farm was near Lea House Road; Two Gates Farm was by the junction of Sycamore Road and Willows Road; Barnbrook Farm was by the cross-roads of Linden Road and Bournville Lane; Row Heath Farm was at the junction of Franklin Road and Oak Tree Lane, and Barnbrook Hall Farm later became the recreation ground for female staff at Cadbury’s; Fordhouse Farm was half way up Fordhouse Lane near The Worthings; Bullies Farm was located on Cartland Road, close to the junction with Pineapple Road; Pineapple Farm was at the bottom of Vicarage Road, just across the railway lines from Hazelwell Hall; Dawberry Farm stood near Dawberry Fields Road and Harton Way.[52]

Estates and high status residences[edit]

Breedon House: The 1840 Tithe Map shows that John Lane Snow owned Breedon House on the estate of which is now Cotteridge Primary School. The house and estate was occupied by the Baldwin family, papermakers (whose principal mill was off Lifford Lane), between c.1860 and c.1895.[53] The Old Cross Inn was sold c. 1900 and the owner moved to larger premises on the other side of the canal to enable the expansion of the screw factory. Stirchley Village starts at the foot of Breedon Hill.

Transport and communications[edit]

Pershore Road (A441)[edit]

King’s Norton village was connected to Birmingham by a minor rural track until it reached the road from Alcester to Balsall Heath which was turnpiked in 1767. There was no Pershore Road until an Act of 1825 authorised the construction of the Pershore Turnpike.[54] This new road from Birmingham to Redditch began near Smithfield Market and headed south through Edgbaston Parish (Warwickshire) to Pebble Mill where the Bourn Brook marks the former county boundary. It continued through Northfield Parish (Worcestershire) past Moor Green to Ten Acres, where it crossed the watercourse of the Bourn into King’s Norton Parish. This particular section of the road does not appear on either the first series OS Map or the 1839 Tithe maps.[55] A surveyors plan for the sale of Dogpool Mill on 15 July 1847 names the stretch of road from the Bourn to Dogpool Lane as ‘New Street’ and the continuation of this to Birmingham as ‘New Pershore Road’.[56] The new road created a one way system as it appears that a small hamlet had formed at the junction of Bournville Lane and Hazelwell Street. The Pershore Road joined the old Roman Road as far as Breedon Cross and went straight up the hill to Cotteridge which was probably little more than a farmstead. It went down the hill towards the manorial mill and up to King’s Norton village. The new road that bypassed King's Norton Green was not authorised until 1834 although the section to West Heath had been constructed in 1827.[57]

Public transport was by horse-drawn bus operated by City of Birmingham Tramways Co.[58] The building that became Halford Coach Trimmers was once the stable for the horses that pulled the horse-drawn tram. Its concrete floor had drainage grooves set into it.[59] Under the powers of 1901 the King’s Norton and Northfield UDC constructed a tramway along the Pershore Road, and a short connecting line along Pebble Mill Road was constructed to link the Bristol Road section with the new line. As the Bristol and Pershore Roads were so closely related, arrangements were made for CBT to work the new line on behalf of the two councils until the lease of the Bristol Road section expired in 1911. CBT cars began working to Breedon Cross on 29 May 1904, and through to Cotteridge on 23 June 1904.[60] The addition of another 40 cars became necessary when it was realised that many of the 30 cars operated by CBT on the Selly Oak and King’s Norton routes were in such poor condition that they could not be counted upon for regular service when due for acquisition in July 1911.[61]

In 1911, Birmingham Corporation Tramways took over the operation.[62] At the beginning of World War I the Pershore Road line had been doubled between Pebble Mill Road and Cotteridge. At Ten Acres where, because of the narrowness of the road, a single track with a passing loop was retained. The single track in Pebble Mill Road was doubled and placed on the central reservation between dual carriageways, the first use of this layout in Birmingham.[63] World War I brought difficulties to all undertakings and Tramways were no exception. Buses were impressed for military use, staff shortages became acute giving rise to the appearance of conductresses, costs rose and supplies of all kinds became difficult to obtain.[64] The upper saloon bulkheads were replaced by half-glazed partitions enclosing new quarter-turn staircases, at the head of which doors were provided. The suggestion of saloon handrails on these partitions was suggested initially by a regular passenger, R A Howlett, who lived in Stirchley. The scope of his proposed scheme was enlarged and handrails were provided for the whole length of the partitions.[65] The eight cars stationed at either the Bournbrook or Cotteridge depots were painted in the chocolate and cream livery when taken over in July 1911.[66] Wartime grey livery was applied to some cars with them being repainted in the standard livery when next overhauled between July 1945 and April 1946.[67] The line closed in 1952 and the depot was demolished and replaced with Beaumont Park Sheltered Housing.[68]

Canals[edit]

After protracted arguments on 10 June 1791 the Worcester and Birmingham Canal Bill received the Royal Assent.[69] It involved the expertise of civil engineers in the construction of tunnels, cuttings and embankments with aqueducts over roads, rivers and streams. An early wooden accommodation draw-bridge at Leay House Farm, located where Mary Vale Road now crosses the canal, was replaced by a brick bridge in 1810. The route of the canal didn’t respect farm and estate boundaries: "Unfortunately this work meant the destruction of growing wheat on the land of Mr Guest of Barnbrook, and he was promised compensation for his crops, as were other farmers similarly affected on the line of the canal as the work proceeded."[70] The labourers, who had travelled to the area, were housed in barracks possibly large wooden huts that could be moved to other sites as the work progressed. Food, beer and other domestic needs were serviced by the local community, who also provided skilled work as carpenters, blacksmiths, and brickmakers. The canal was completed in 1815 although sections had been opened when completed and had enabled a route from Dudley to London. The Lapal, or Dudley 2, connection from Netherton to Selly Oak had been opened on 28 May 1798. The Stratford-upon-Avon Canal joined the Worcester and Birmingham canal near King’s Norton village and was fully opened in 1816. An unusual guillotine lock was installed to control the difference in height of the water. This is now a scheduled ancient monument.[71] Wharves were built to offload supplies of coal and lime which were then distributed by horse-drawn carts.

Railways[edit]

In 1828 powers were obtained to build a railway or tramway (sic) from Bristol to Gloucester and in 1836 another Act authorised the route from Gloucester to Birmingham. This line was opened on 17 December 1840 with a terminus at Camp Hill and on 17 August 1841 trains commenced running into the London and Birmingham Terminus at Curzon Street.[72] Lifford has had three stations. The first Lifford railway station opened 1840–1844; The Birmingham West Suburban Railway opened the second station on its line which closed in 1885. The third station was on the Camp Hill line and closed in 1941.[73] The station at King’s Norton (Cotteridge) opened in 1849. Another station that served Stirchley was Hazelwell at the top of what would become Cartland Road.

Construction of the Birmingham West Suburban Line began in 1872. This required expanding the canal embankment. A section of the canal had to be drained to complete the work scheduled to last for a week. The canal was to be re-watered through a valve in the southern stop-gate but someone opened the gate and water from as far as Tardibigge rushed towards Birmingham "like a great tidal wave" resulting in a breach of the canal in Edgbaston and causing damage to a number of canal boats. The water spent itself in Charlotte Road where the culverts carried away an immense quantity. It was a major event for the emergency services and the navvies, and witnessed by a multitude of people who turned up to witness the devastation. The railway opened on 3 April 1876 with a station at Stirchley Street (now Bournville). By this time the Midland Railway Company had taken over the Birmingham West Suburban Railway and in 1881 obtained an act for doubling the track and creating a direct route to King’s Norton that avoided the Lifford Loop.[74]

Midland Railway Company Engine Shed The opening of Lifford curve in July 1892 allowed for a more intensive local service. New sidings were opened at Cadbury’s and Selly Oak in 1885 and by 1892 Selly Oak was handling over 55,000 tons of goods traffic and Lifford over 17,000 tons. The Midland Railway Company identified an available site near Stirchley Street which was bordered by the Birmingham West Suburban main line, Cotteridge Park, Breedon Road, and Mary Vale Road. Land was purchased from the Trustees of the late J Hock. The engine roundhouse was built by Messrs. Garlick and Horton at a cost of £11,546 and Eastwood Swingler gained the contract for a 50’ turntable. Construction began in 1893 and the shed opened on 12 March 1894. Although named Bournville Engine Shed it was unrelated to Bournville Model Village. The shed was significant during World War I and drivers and firemen were classified as being in a Reserved occupation. The lighter Engines required for the Dowery Dell viaduct operated from Lifford taking empty wagons on the outward journey and returning with loads, usually steel tubes and coil, manufactured in the Halesowen area. The arrival of diesel driven units and the 1950s rationalisation of the railway programme meant the end of the shed. It closed on 2 February 1960. It became the new ‘Parkside’ distribution centre for Cadbury’s. By 1971 Cadbury’s had switched from rail to road transport so the depot became surplus to requirements and was demolished and replaced with a housing estate.[75]

Industry[edit]

Guest, Keen, and Nettlefold Ltd: James and Son constructed a screw making factory at Breedon Cross in 1861-2.[76] In 1864 William Avery joined the firm and the company name changed to James, Son, and Avery.[77] Joseph Chamberlain (senior) gave financial support to his brother-in-law, John Sutton Nettlefold, to secure at a cost of £30,000, the English rights to an American screw making machine. In 1866 Nettlefold and Chamberlain moved into the factory at Breedon Cross. The company was managed by the sons of the owners, Joseph Chamberlain and Joseph Henry Nettlefold. Joseph Chamberlain left the company in 1874 to concentrate on politics. In 1880 the company was incorporated as Nettlefolds Ltd, the various firms incorporated were those of Messrs Nettlefold’s, at Heath Street, and Princip-Street, Birmingham, and at King’s Norton.[78] and later, in 1902, became part of Guest, Keen, and Nettlefold (GKN).

Boxfoldia: in 1924 Boxfoldia moved to the Ten Acre Works. They manufactured cartons for well-known companies such as Colman's, Reckitt Benckiser, and the Dunlop Rubber Company. The founder, Charles Henry Foyle, believed that business was a partnership between employer and employee, and set up a Works Council. By 1933 these works had become too small and Boxfoldia moved to Dale Road, in Bournbrook[79] From 1934 the site was then taken over by Cox, Wilcox & Co who were manufacturers of domestic Hardware. Ten Acre Mews, a small housing development now occupies the site.[80]

Capon Heaton: Hazelwell Mill was established in the late 17th century to grind corn for the sub-manor of Hazelwell in Kings Norton. In about the mid-18th century it was converted to the boring and grinding of gun barrels. By 1904 the earlier watermill had been demolished. Edward Capon and Harry Heaton entered into a partnership in 1883. As Capon-Heaton and Company they manufactured India-rubber at Lifford until the mid-1890s when the firm moved to Hazelwell, the next mill downstream where they continued until acquired in 1964 by Avon India Rubber Co.[81] In 1978-9, The Stirchley Industrial Estate was built over the original mill and mill pool site.

Eccles Caravans: In 1913 A J Riley and his son built his first recreational vehicle by putting a caravan body onto a Talbot car chassis. After World War I ended the Riley’s decided to invest in a motor haulage company that was having difficulty. It was called the Eccles Motor Transport Company. By the late 1920s the factory had outgrown its premises and moved to a 4-acre site in Hazelwell Lane, Stirchley, where a modern, single story factory was built. Believed to be the first purpose built caravan factory of its kind in the World it was fitted with the latest high tech woodwork machinery. It was here that 'overrun brake systems' were invented and these are still fitted on caravans produced today. During World War II orders for caravans virtually stopped however the Eccles factory survived by adapting to the war situation. Commissioned by the British Military Authorities the Eccles factory still produced caravan bodies but these were used as portable workshops and radio offices. The factory also built ambulances and search light vehicles. By 1960 Bill Riley had retired, shutdown the factory and sold it to Sprite Caravans who moved production to their factory in Newmarket.[82]

The Hampton Works Company in Twyning Road, was a manufacturer of custom precision pressings. The building was designed by Bradley and Clark of Temple Row, Birmingham in 1934. It was extended c.1939 by the same architects and air raid shelters were built at the same time to the west of the existing factory buildings. It is a listed building now occupied by Rivfast Ltd. The buildings are of plum-coloured brick laid in Flemish bond with decorative bands of brown brick dressings and partially glazed pitched roofs and metal-framed windows. The decorative motifs are in an Art Deco style.

Jesse Hill Gunmakers, Ash Tree Road, is a family business that began in 1921. The building is listed.[83]

R J Hunt & Sons: The iron foundry was acquired by J Brockhouse and Co in 1937 and continued to trade as Brockhouse Hunt. They produced cast iron products from scrap and other metal using sand from Bromsgrove. The site is now derelict and will potentially become a small housing estate.[84]

Rubberplas BSP Ltd, Mary Vale Road, manufactures Rubber Moulding, Thermoplastic Moulding & Vacuum Metallizing for automotive and domestic industries. It also launched the Golf Grass Mat used to install permanent or temporary walkways around Golf Courses.

Edwin Showell and Sons: Showell and Barnes were founded in 1790, in Loveday Street. By 1820 they were trading as Edwin Showell and Sons, manufacturing door springs and architectural brassware. After Edwin died his two sons, Charles and Edwin Alfred ran the company. The move to the Stirchley Brass Foundry in Charlotte Road took place in c1902. The property included an attractive Elizabethan red brick farmhouse, called Ivy House or Nine Elms into which Charles Showell moved. The factory gradually expanded to include the whole site and the farmhouse, which had fallen into disrepair, was demolished. During World War I they produced 100,000 Enfield oilers for Birmingham Small Arms Company rifles. In 1956 they were taken over by Josiah Parkes and Sons.[85]

Community[edit]

Stirchley Neighbourhood Forum[edit]

Stirchley Neighbourhood Forum represents all residents of Stirchley. The forum holds a monthly open meeting attended by police and the local councillor.[86]

Ten Acres and Stirchley Street Co-operative Society (TASCOS)[edit]

This co-operative society was formed by a group of traders who met in Ten Acres School (now Darris Road). The front room and cellar of a house at 112 Hazelwell Street was rented, trading stock was bought, and on 25 June 1875 the first shop was opened. The success was such that bigger premises were necessary and in 1893 the Stirchley Street Central Premises was opened. Adjoining shops and cottages were acquired and the Central Premises was extended. The Drapery and Footwear Departments were trading in 1893 from the first Central Premises. By 1913 further expansion resulted in the construction of a new building at the corner of Hazelwell Street and Umberslade Road. Throughout the district various shops became branches where members could recite their ‘divvy’ number and be rewarded by collecting a dividend for shopping in the TASCOS chain of stores. Initially bread was made at a bake-house at the rear of the old Central Premises until larger premises were opened in 1905 and even larger premises were acquired in Mary Vale Road in 1929. The Central Butchery was established in 1913. By 1914 the model dairy in Ribblesdale Road was distributing 5,000 gallons of milk a week. Although TASCOS began trading in coal in 1898 the site at Lifford was not operational until 1917. The furnishing department opened in 1915. A Hairdresser (1926), a chemist (1928), and the Funeral Department (1932) were also opened. The laundry moved from Mary Vale Road to Bewdley Road where it opened in 1939 at a cost of £36,000. The building was a target in 1940 air raids. The Co-Operative movement had an ethos of Education and Social Activities. A sports pavilion was erected on ground purchased near Lifford. By 1951, the membership had grown to over 60,000 and the office staff to 192. After a short period of administration by the Co-operative Wholesale Society in 1971 TASCOS was absorbed into the Birmingham Co-operative Society.[87]

The co-op food store ceased trading in Stirchley on 25 January 2020, ahead of Morrisons supermarket taking over the building.[88]

Housing[edit]

Much of Pershore Road from Cotteridge to Pebble Mill is lined with artisans houses built from the 1870s. Many of the side roads have similar houses and there are also unique terraces, Derwent Cottages, and Rose Cottages that lie behind the Pershore Road. The main builders were Grant’s Estates and they often gave the terraces names and the date of construction. Grant’s Estates was founded by brothers Thomas James Grant and Henry Michael Grant in the 1890s. Groups of terraced housing in Cotteridge and King’s Heath, stable blocks, and other jobbing work in 1897 can be traced to the company. They concentrated on buying building plots on green field sites, laying out the roads and drainage, and letting the properties. Their business premises were next to the railway bridge in Cotteridge. Sewell’s acquired the business in 1961. The family lived in a house called Falcon Hill which became a police station in the 1960s and was replaced by Grant’s Court ten years later. The family name is preserved in the Grant Arms pub. Mrs Ellen Grant Ferris bought Harvington Hall, in 1920, which she gave to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Birmingham.[89]

The houses on the East side of the Pershore Road from Ten Acres heading towards Pebble Mill are known as the ABC houses as they are named in alphabetical order after places in Britain. The ambitious project only got as far as J for Jarrow.[90]

Parks and open spaces[edit]

Stirchley Park is a pocket park between Hazelwell Street and Bond Street.[91] There is mown grass with mature as well as recently planted trees and a few benches. A wall by the park has some professional Graffiti. The park once had a competitive bowling club with a green and pavilion for the players. This had not been used for many years and, as part of a Community Asset Transfer, will become the car-park for the new Community Centre. The park has now been established as the venue for the annual Stirchley Festival. The vehicular entrance to the park is being improved by the demolition of an extension to the listed Friends Meeting House. It is likely that the Farmers Market will also relocate to this site. Hazelwell Park was the former venue for the festival but major works to address issues of flooding meant it was temporarily unavailable and the new location fits in well with the regeneration of Stirchley. Near Hazelwell Park, still known to some as Newlands Park, there are significant community allotments. Ten Acres Park is between Cartland Road and Dogpool Lane where the former head race for the mill was cut from the Bourn and the River Rea. The community has suggested the creation of a natural wetland area on land subject to flooding. Holders Lane Playing Fields is on the site of the ancient Farmons Mill. Lifford Reservoir was built near the junction of the Worcester and Birmingham Canal, and the Stratford-upon-Avon Canal, as a supply lake for the nearby mills. It was also a leisure resort with a tea shop, boating and fishing.[92] During the 1920s and 1930s there were tea rooms, boats for hire, and fishing at Dogpool Mill pool.[93]

Cinemas and library[edit]

Picturedrome, Hudson Drive: It was opened on the site of Hudson Brothers Ltd in 1913 but Cotteridge Cinema Ltd went into liquidation in 1932. It is now a factory unit and a small estate has been built on the former industrial land at the end of the Drive.[94]

Savoy Cinema, Breedon Cross: This building was opened in 1922 as the ‘Palace of Varieties’. Ten years later the name was changed to the Savoy and it closed in 1958. The building continued in use as Wyvern Engineering.[95]

Empire, Pershore Road: It opened in 1912 to the design of architects Wood and Kenrick of Colmore Row.[96] William Astley, father-in-law of Sidney Clift, who started the Clifton Circuit, was the first proprietor of the Empire.[97] The cinema, known locally as the ‘Bug House’, had closed by 1950. The building was then used as a car hire depot.[98]

Stirchley Pavilion, Pershore Road, was designed by Harold Seymore Scott and opened on 18 November 1931 by Alderman Sir Percival Bower. In 1931 a large house was demolished, an orchard ploughed up, and the Cinema was built. The promoters included Joseph Cohen who owned the News Theatre in Birmingham. The Pavilion’s at Stirchley and Wylde Green were intended as the first of a chain of Pavilions throughout the Midlands. However, the idea was abandoned and they became ABC houses.[97] It had a seating capacity of 2,500 and a restaurant. A Ten-pin bowling alley was built next to the cinema which closed in 1968. After alterations it became ‘The Star’, a Bingo (United Kingdom) and bowls venue. Part of the building is now Fitness First.[99]

The area is served by Stirchley Library.

Public houses[edit]

The earliest pubs were the Cross Inn, that was relocated to build the GKN works and the Black Horse where Stirchley Baths was built.[28]

The Three Horseshoes public house existed in 1836 although it was rebuilt in the 1920s. It was also used as a meeting place to auction local plots of land.[100] The Inn sold Davenports’ Celebrated and Noted Bottled Ales and Stouts. Davenports operated a ‘beer at home’ delivery service.[101] In 2020 the pub was refurbished and opened under the new name of The Bournbrook Inn.[102] It includes a bar, restaurant and 53 rooms and is operated by Westfield Leisure.

The British Oak was a small beer house that was rebuilt in 1926.[103] The new building was designed by Mr Brassington, who had designed the Barton Arms some twenty two years earlier. At the rear is a bowling green, gardens, and a children’s playground.[104]

The New Dogpool Hotel was previously on the opposite corner on Dogpool Lane where the Birmingham Municipal Bank was opened in 1928. It replaced the Ten Acres Tavern, a Holt’s pub, which stood at the junction of St Stephen’s Road and dates from 1923.[105] It has changed names a number of times.

Further along the Pershore Road is the Selly Park Tavern with its bowling green and skittle alley. Formerly the Pershore Road Inn and then the Selly Park Hotel, it was built on land owned by the brewer Sir John Holder whose initials appear on the centre gable. After 1920 Holders Brewery was acquired by Mitchells & Butlers. The Tavern has a separate skittle alley in what may have been the earlier inn’s outbuildings. It also has a bowling green.[106]

The Highbury marks the boundary with Moseley and King’s Heath Ward. The Lifford Curve suffered the same fate as the Breedon Bar being burnt beyond repair. The Hazelwell was built on the site of Hazelwell Hall.

The Lifford Curve public house was located on Fordhouse Lane. The name of the pub was taken from the nearby curve in the Camp Hill line.The building was badly damaged by a fire in May 2010.[107] The pub was later demolished and the site sold for redevelopment. The site is now occupied by Thrifty Car Rental

The Breedon Bar was closed in 1993. It was a listed building but was so badly damaged by a major fire that it had to be demolished. It is now an apartment block.[108]

Between 2015 and 2019, the area saw a sudden increase of micropubs, bars and breweries (with adjacent tap houses) launch either on or near the Pershore Road. This included The Wildcat Tap, Cork & Cage, Artefact, Attic Brew, Glasshouse Brewery and the Birmingham Brewing Company. In 2019, the Couch cocktail bar opened (also selling beer). The area became colloquially known as the Stirchley Beer Mile and often also included Cotteridge Wines and Stirchley Wines off licenses as well as the long established British Oak pub.[109]

Stirchley Baths[edit]

On 25 June 1911, Stirchley Baths in Bournville Lane were opened to the public by King's Norton and Northfield Urban District Council. These were the second baths constructed by the council with the other being located on Tiverton Road, Bournbrook. Later that year, the baths were taken over by the Birmingham Baths Committee. The baths contained one swimming pool with a spectators' gallery, private baths for men and women and a small steam room. In the winter months, the swimming pool was floored over and the room was used as a hall. The private baths service was discontinued after the baths were taken by the City of Birmingham Baths Department shortly after opening. An unusual feature of the baths was a system of aeration and filtration of the water, which was obtained from the council's mains supply and continuously filtered. This was one of the first uses of such a system in swimming baths in the country and it was later introduced and installed in all baths in all local authorities. Swimming baths usually obtained the water from deep wells constructed beneath the premises.[110]

These baths are a grade II Listed building but were closed in 1986 and became tumbledown. In January 2015 a building refurbishment project began, using money from the sale of the old Community Centre (as part of a supermarket redevelopment) and a £1 million community development grant. The building reopened as a community centre in January 2016.[111]

Pictures of the derelict state of the baths can be viewed here[112] and here.[113]

The ongoing building project and associated community activities can be viewed here.[114]

Places of worship[edit]

Church of Ascension: construction of the Church of Ascension began in 1898 on Hazelwell Street on land adjoining the Church School and School House. These later became the church hall. Construction was completed in 1901 and it was consecrated by the Bishop of Coventry on 30 October 1901. It was designed by W. Hale as a Chapel of ease to St. Mary's Church in Moseley. A separate Parish was assigned to it in 1912 out of the parishes of St. Mary's, Moseley and St. Nicolas, Kings Norton. On 1 December 1927, a daughter church dedicated to St. Hugh of Lincoln serving the Dads Lane estate was opened in Pineapple Grove. A new parish of St Mary Magdalene, Hazelwell, was created, taking in part of Stirchley parish. During World War II the church hall was taken over by the ‘British Restaurant’.[115]

On 29 October 1965, the Church of Ascension was destroyed by fire and was demolished. Services continued at St Hugh's. A new church, designed by Romilly Craze, was constructed next to St. Hugh's and was consecrated by the Bishop of Birmingham on 14 July 1973. Surviving features from the original church, such as some of the stained glass, the Stations of the Cross, the altar silver, the processional crosses and the vestments, were used in the new church. St. Hugh's became the church hall for the new Church of Ascension A new vicarage was built on land behind the church in 1992. The Church of Ascension is a large building with an octagonal main church, and a church hall. There is also a chapel, and a large organ on an upper balcony in the main building.

Andrew Cohen Residential Care home constructed a small private Synagogue for the benefit of its residents, staff, and visitors.

Christadelphians, Hazelwell Street. The institute, formerly the Friends Institute, was in use for Christadelphians meetings in 1941 to 1954.

Christ Church: Pershore Road, Selly Park

Friends meeting house, Hazelwell Street. Hazelwell Street: A meeting room was in use from 1882 to 1892. At first it was a small dining room near Mosley’s Lodge by Stirchley station. The meeting owed its foundation to the removal in 1879 of Cadbury’s cocoa and chocolate works from Bridge Street, Birmingham, to their new site at Bournville, and the consequent migration of management and staff, some of whom were Quakers. It was preceded by Christian Society meetings at the Stirchley Street Board School, started in 1879. The congregation moved in 1892 to Stirchley institute.

Gospel Mission Hall: 1937

Islam: St Stephen’s Road and Pershore Road.

Kingdom Hall for Jehovah's Witnesses

Stirchley Community Church

The Salvation Army used the top floor of Jesse Hill’s premises in Ash Tree Road for children’s services. A new building was constructed in 1914 near Hazelwell Street. The building became a retail tile warehouse and has recently been demolished for a new supermarket development.[116]

Selly Park Baptist Church: The original Dogpool Chapel, St Stephen’s Road, was a gift from Mr Wright of a chapel from Acocks Green. It was moved and re-erected by Mr Johnson and the first service was held on the first Sunday in May 1867. William Middlemore made a substantial contribution of £2,600 for a new permanent church that was opened in 1877 and officially established the following year. The wooden building was extended in 1874 and Sunday school classes began two years later. This building was moved to the site of the current school hall.[117]

St Andrews Methodist Church: Cartland Road: the Primitive Methodists had held meetings in local cottages until 1906 when a corrugated iron building was erected. At first it was called the Cartland Road Methodist Church but when the Selly Park church closed and the congregations amalgamated a new building was constructed and it was consecrated as St Andrews.[118]

Stirchley Institute and Elim Pentecostal: Hazelwell Street:

Stirchley Methodist Chapel, Mayfield Road was built in 1897 by the Methodist New Connection and once had a lovely garden with iron railings in front. The main hall could seat 136 people and there were two other rooms. After World War II the chapel was used as an annexe to Stirchley School. It ceased to be registered for public worship in 1956.[119] The Stirchley Young Men’s Association (YMA) was connected with the Chapel in Mayfield Road. The building is now used as storage space for a private business.[120]

Wesleyan Chapel: Stirchley Street 1839

Neighbouring estates[edit]

Pineapple Farm estate[edit]

Pineapple Farm council estate was developed in the 1920s and 1930s in the east of Stirchley and from 1923 was served by a primary school, which opened initially with space for 400 pupils, at a site on Allen's Croft Road. However, an annex was opened at Hazelwell Parish Hall in 1930 to accommodate growing pupil numbers, before the main site was finally expanded to create a 14-class (two-form entry) 5-11 school in 1952. The school buildings were replaced in 2007, by which time they were all between 55 and 84 years old.[121] During World War II, a number of bombs aimed by the German Luftwaffe at local factories fell on the Pineapple Farm estate, resulting in eight deaths, account for all but three of the 11 air raid fatalities at Stirchley during the war.[122]

References[edit]

- ^ "Stirchley Ward Map" (PDF). Birmingham.gov.uk. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ "These are the coolest neighbourhoods in the UK". Cntraveller.com. 4 June 2020.

- ^ Hansard: Local Government Provisional Order (No 13) Bill (HC Deb 16 February 1911 volume 21 cc1321-53)

- ^ Briggs, Asa: History of Birmingham, Volume II, Borough and City 1865–1938 (OUP 1952) chapter 5

- ^ Manzoni, Herbert J: Report on the Survey –Written Analysis (Birmingham City Council 1952) p. 7

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964) page xv

- ^ a b Lock, Arthur B: History of King’s Norton and Northfield Wards (Midland Educational Company Ltd) p. 128

- ^ Item 253503, A catalogue of the Birmingham collection, Birmingham Public Libraries

- ^ English Heritage Building ID: 217669, NGR: SP0456781423

- ^ Demidowicz, George: Selly Manor, The Manor House that never was. (2015)

- ^ Derby Mercury BL_0000189_17830807_012_0003.pdf

- ^ Chinn, Carl: One Thousand years of Brum (Birmingham Evening Mail 1999) p. 144

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964) p. 541

- ^ Demidowicz, G and Price S: King’s Norton – A History (Phillimore 2009) p. 1

- ^ Chinn, Carl: One Thousand years of Brum (Birmingham Evening Mail 1999) p. 36-37

- ^ a b Tithe Map and Apportionment of Northfield Parish, Worcestershire 1839

- ^ "Parishes: Northfield | British History Online". British-history.ac.uk.

- ^ Messrs James and Lister Lea: Plan of Middleton Hall Freehold Building Estate August 23rd 1877

- ^ Baker, Anne: A study of north-eastern King’s Norton: ancient settlement in a woodland manor (BWAS Transactions 107, 2003) p. 145

- ^ Gelling, Margaret: Signposts to the Past (Phillimore 1997) p. 94

- ^ Demidowicz, G and Price S: King’s Norton – A History (Phillimore 2009) p. 6

- ^ Hodder, Michael: The Archaeology of Sutton Park (History Press 2013) p. 55

- ^ Dean, Stephen; Hooke, Della; FSA; Jones, Alex: The ‘Staffordshire Hoard’: The Fieldwork (Antiquaries Journal 90, 2010) p. 150

- ^ Muirhead, J H: Birmingham Institutions (Cornish Brothers, Birmingham 1911), Chapter 1: Barrow, Walter: The Town and its Industries, p. 5

- ^ Leather, Peter: Birmingham Roman Roads Project

- ^ Gelling, Margaret: Signposts to the Past (Phillimore 1997) p. 155

- ^ Hooke, Della: The Anglo-Saxon Landscape – the Kingdom of the Hwicce (MUP 1985) p. 145

- ^ a b Tithe Map and Apportionments of Northfield Parish, Worcestershire 1839

- ^ Demidowicz, G and Price S: King’s Norton – A History (Phillimore 2009) p. 7

- ^ Demidowicz, G and Price S: King’s Norton – A History (Phillimore 2009) p. 11

- ^ Morris, John (General Editor): Domesday Book 16 Worcestershire (Phillimore 1982) folia 172b

- ^ Baker, Anne: A study of north-eastern King’s Norton: ancient settlement in a woodland manor (BWAS Transactions 107, 2003) p. 141

- ^ Morris, John: Domesday Book 23 Warwickshire (Phillimore 1976)

- ^ Axinte, Adrian: Mapping Birmingham’s Historic Landscape (Birmingham City Council 2015)

- ^ Morris, John: Domesday Book 24 Staffordshire (Phillimore 1976)

- ^ Morris, John: Domesday Book 16 Worcestershire

- ^ Briggs, Asa: History of Birmingham, Volume II, Borough and City 1865–1938 (OUP 1952) Chapter 5

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964) p. 246

- ^ Morris, John (General Editor): Domesday Book 16 Worcestershire (Phillimore 1982)

- ^ Morris, John (General Editor): Domesday Book 24 Staffordshire (Phillimore 1976)

- ^ Page, William (Editor) University of London Institute of Historical Research: VCH Worcestershire Volume 2 (Dawson's of Pall Mall 1971 reprinted from the original edition of 1906) pp. 4 & 95

- ^ Baker, Anne: A study of north-eastern King’s Norton: ancient settlement in a woodland manor (BWAS Transactions 107, 2003) p. 140

- ^ Gelling, Margaret: Signposts to the Past (Phillimore 1997) p. 69

- ^ Chapelot, Jean and Fossier, Robert: The Village and House in the Middle Ages (Batsford 1985) p. 79

- ^ English Heritage Building ID: 217596, NGR: SP0547582485

- ^ Tithe Map: Northfield Parish, Worcestershire

- ^ Historic Environment Record MBM862 Selly Manor Moat 1066–1539

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964) p. 261

- ^ Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964) pp. 261-2

- ^ a b Stevens, W B (Editor): VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham (OUP 1964) p. 262

- ^ Cale, M.,'Ephemeral and essential: the development of the paper industry in Birmingham,' The Local Historian, vol. 51, issue 2 (April 2021), p. 137-153

- ^ Chinn, Carl: One Thousand years of Brum (Birmingham Evening Mail 1999) p. 23 & p. 145

- ^ M. Cale, 'Essential and Ephemeral: The development of the paper industry in Birmingham.' The Local Historian, 51(2), Apr. 2021

- ^ Demidowicz, G and Price S: King’s Norton – A History (Phillimore 2009) p. 101

- ^ Tithe Map and Apportionments of Northfield Parish, Worcestershire 1839

- ^ "Plan of Freehold Property at Stirchley Street near Birmingham to be sold at Auction by Mr J Fallows on 15th July 1847"

- ^ Demidowicz, G and Price S: King’s Norton – A History (Phillimore 2009) p. 148

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Stirchley, Cotteridge, and Selly Park on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) No 1

- ^ Chew, Linda: Images of Stirchley (1995) p. 37

- ^ Hardy, P L & Jaques, P: A Short Review of Birmingham Corporation Tramways (H J Publications 1971) p. 11

- ^ Lawson, P W: Birmingham Corporation Tramway Rolling Stock (Birmingham Transport Historical Group 1983) p. 45

- ^ Demidowicz, G and Price S: King’s Norton – A History (Phillimore 2009) p. 164

- ^ Hardy, P L & Jaques, P: A Short Review of Birmingham Corporation Tramways (H J Publications 1971) p. 41

- ^ Hardy, P L & Jaques, P: A Short Review of Birmingham Corporation Tramways (H J Publications 1971) p. 40

- ^ Lawson, P W: Birmingham Corporation Tramway Rolling Stock (Birmingham Transport Historical Group 1983) p. 106

- ^ Lawson, P W: Birmingham Corporation Tramway Rolling Stock (Birmingham Transport Historical Group 1983) p. 71

- ^ Lawson, P W: Birmingham Corporation Tramway Rolling Stock (Birmingham Transport Historical Group 1983) p. 111

- ^ Pearson, Wendy: Cotteridge through time (Amberley 2011) p. 71

- ^ White, Reverend Alan: The Worcester and Birmingham Canal – Chronicles of the Cut (Brewin 2005) p. 19

- ^ White, Reverend Alan: The Worcester and Birmingham Canal – Chronicles of the Cut (Brewin 2005) p. 35

- ^ Pearson, Wendy: King’s Norton Past and Present (Sutton Publishing 2004) p. 114-115

- ^ Jenson, Alec G: Birmingham Transport: a History of Public Road Transport in the Birmingham Area, (Birmingham Transport Historical Group, 1978) p. 9

- ^ Pearson, Wendy: Cotteridge through time (Amberley 2011) p. 68

- ^ White, Reverend Alan: The Worcester and Birmingham Canal – Chronicles of the Cut (Brewin 2005) p. 186-189

- ^ Sharpe, Derek: The Railways of Cadbury and Bournville. (Bournbrook Publications and Derek Sharpe 2002) pp. 51-100

- ^ Demidowicz, G and Price S: King’s Norton – A History (Phillimore 2009) p. 144-145

- ^ Chew, Linda: Images of Stirchley (1995) p. 46

- ^ Showell, Walter: Dictionary of Birmingham (Walter Showell and Sons 1885) p. 321

- ^ Pearson, Wendy: Selly Oak and Bournbrook through time (Amberley 2012) p. 23

- ^ Butler, Joanne; Baker, Anne; Southworth, Pat: Selly Oak and Selly Park (Tempus 2005) p. 38

- ^ Demidowicz, G and Price S: King’s Norton – A History (Phillimore 2009) p. 139

- ^ Chew, Linda: Images of Stirchley (1995) pp. 52-53

- ^ Chew, Linda: Images of Stirchley (1995) p. 5

- ^ Pearson, Wendy: Cotteridge through time (Amberley 2011) p. 44

- ^ Chew, Linda: Images of Stirchley (1995) p. 54

- ^ "Stirchley Forum - Representing Stirchley Residents". Stirchleyforum.co.uk.

- ^ Chew, Linda and Anthony: TASCOS, Ten Acres and Stirchley Co-Operative Society, A Pictorial History (2015)

- ^ "As Stirchley Co-op shuts its doors we look back at 100 years of history". Birminghammail.co.uk. February 2020.

- ^ Rathbone, Niky: The Grants Estates and the Avenues

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Stirchley, Cotteridge, and Selly Park on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) Image 51

- ^ "A Brummie's Guide to Birmingham: Stirchley Park". Brummiesguidetobirmingham.blogspot.com. 5 July 2012.

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Stirchley, Cotteridge, and Selly Park on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) image 18

- ^ Butler, Joanne; Baker, Anne; Southworth, Pat: Selly Oak and Selly Park (Tempus 2005) p. 26

- ^ Pearson, Wendy: Cotteridge through time (Amberley 2011) p. 93

- ^ Pearson, Wendy: Cotteridge through time (Amberley 2011) p. 94

- ^ Chew, Linda: Images of Stirchley (1995) p. 27

- ^ a b Clegg, Chris and Rosemary: The Dream Palaces of Birmingham, (1983) p. 49

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Stirchley, Cotteridge, and Selly Park on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) Image 36

- ^ Chew, Linda: Images of Stirchley (1995) p. 24

- ^ Chew, Linda: Images of Stirchley (1995) p. 16

- ^ Marks, John: Birmingham Inns and Pubs (Reflections of a Bygone Age 1992) p. 1

- ^ "Home". Bournbrookinn.co.uk.

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Stirchley, Cotteridge, and Selly Park on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) image 34

- ^ Chew, Linda: Images of Stirchley (1995) p. 32

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Stirchley, Cotteridge, and Selly Park on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) images 45 and 46

- ^ Butler, Joanne; Baker, Anne; Southworth, Pat: Selly Oak and Selly Park (Tempus 2005) p. 102

- ^ "Pub in Stirchley left gutted by blaze". 23 May 2010.

- ^ White, Reverend Alan: The Worcester and Birmingham Canal – Chronicles of the Cut (Brewin 2005) p. 312

- ^ "The Stirchley Beer Mile". Thebrewerybible.com.

- ^ Moth, J., (1951) The City of Birmingham Baths Department 1851 - 1951

- ^ Elkes, Neil (11 January 2016). "Official opening of historic Stirchley Baths following a £4 million restoration". Birmingham Mail. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Stirchley Local News for Stirchley Birmingham". Stirchley.co.uk.

- ^ "Stirchley Baths – A community hub in restored Edwardian Swimming baths". Stirchleybaths.org. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Chew, Linda: Images of Stirchley (1995) p. 12

- ^ Chew, Linda: Images of Stirchley (1995) p. 30

- ^ Selly Park Baptist Church, 1878–1978 A century of Progress

- ^ Chew, Linda: Images of Stirchley (1995) p. 25

- ^ Chew, Linda: Images of Stirchley (1995) p. 40

- ^ Maxam, Andrew: Stirchley, Cotteridge, and Selly Park on old picture postcards (Reflections of a Bygone Age 2005) Image 20

- ^ "Pineapple : History of Birmingham Places A to Y". Billdargue.jimdo.com.

- ^ [1] [permanent dead link]

Bibliography[edit]

- Baker, Anne (2003). A study of north-eastern King's Norton: ancient settlement in a woodland manor. BWAS Transactions 107.

- Brassington, W Salt (1894). Historic Worcestershire. Midland Educational Company Ltd.

- Briggs, Asa (1952). History of Birmingham, Volume II, Borough and City 1865–1938. OUP.

- Butler, Joanne; Baker, Anne; Southworth, Pat (2005). Selly Oak and Selly Park. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3625-2.

- Chew, Linda (1995). Images of Stirchley. ISBN 0-9526823-0-3.

- Chew, Linda and Anthony (2015). TASCOS, The Ten Acres and Stirchley Co-Operative Society, A Pictorial History.

- Chinn, Carl (1995). One Thousand Years of Brum. Birmingham Evening Mail. ISBN 0-9534316-5-7.

- Demidowicz, George & Price, Stephen (2009). King's Norton A History. Phillimore. ISBN 978-1-86077-562-8.

- Doubleday H Arthur, ed. (1971). VCH Worcestershire Volume 1. Dawson's of Pall Mall. ISBN 0-7129-0479-4.

- Gelling, Margaret (1997). Signposts to the Past. Phillimore. ISBN 978-186077-592-5.

- Goodger, Helen (1990). King's Norton. Brewin. ISBN 0-947731-62-8.

- Hodder, Michael (2004). Birmingham, The Hidden History. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3135-8.

- Hooke, Della (1985). The Anglo-Saxon Landscape, The Kingdom of the Hwicce. MUP.

- Hutton, William (1839). An History of Birmingham. Wrightson and Webb, Birmingham.

- Lock, Arthur B. History of King's Norton and Northfield Wards. Midland Educational Company Ltd.

- Manzoni, Herbert J (1952). Report on the Survey –Written Analysis. Birmingham City Council.

- Marks, John (1992). Birmingham Trams. Reflections of a Bygone Age. ISBN 0-946245-53-3.

- Maxam, Andrew (2005). Stirchley, Cotteridge, and Selly Park on old picture postcards. Reflections of a Bygone Age. ISBN 1-905408-01-3.

- Page, William, ed. (1971). VCH Worcestershire Volume 2. Dawson's of Pall Mall.

- Pearson, Wendy (2011). Cotteridge through time. Amberley. ISBN 978-1-4456-0238-7.

- Pearson, Wendy (2004). King's Norton Past and Present. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-3858-7.

- Stevens, W B, ed. (1964). VCH Warwick Volume VII: The City of Birmingham. OUP.

- Thorn, Frank and Caroline (1982). Domesday Book 16 Worcestershire. OUP. ISBN 0-85033-161-7.

- Tithe Map and Apportionments of Northfield Parish, Worcestershire. 1839.

- Walker, Peter L, ed. (2011). Tithe Apportionments of Worcestershire, 1837–1851. Worcestershire Historical Society.

- White, Reverend Alan (2005). The Worcester and Birmingham Canal – Chronicles of the Cut. Brewin. ISBN 1-85858-261-X.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Evening mail article one last look at the baths

- Images of Stirchley, Linda Chew, Stirchley, Birmingham, B30 3BN, available at level 4 of the reference section of The Library of Birmingham