The Nation

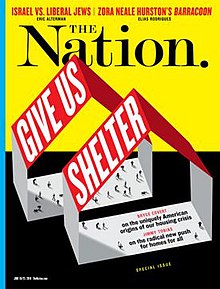

The Nation, cover dated June 18–25, 2018 | |

| Editor | D. D. Guttenplan[1] |

|---|---|

| Former editors | |

| Categories | Political progressive[2] |

| Frequency | Monthly |

| Publisher | Katrina vanden Heuvel |

| Total circulation (2021) | 96,000[3] |

| First issue | July 6, 1865 |

| Company | The Nation Company, L.P. |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | New York City, U.S. |

| Website | thenation |

| ISSN | 0027-8378 |

The Nation is a progressive[2][4] American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator, an abolitionist newspaper that closed in 1865, after ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Thereafter, the magazine proceeded to a broader topic, The Nation. An important collaborator of the new magazine was its Literary Editor Wendell Phillips Garrison, son of William. He had at his disposal his father's vast network of contacts.

The Nation is published by its namesake owner, The Nation Company, L.P., at 520 8th Ave New York, NY 10018. It has news bureaus in Washington, D.C., London, and South Africa, with departments covering architecture, art, corporations, defense, environment, films, legal affairs, music, peace and disarmament, poetry, and the United Nations. Circulation peaked at 187,000 in 2006 but dropped to 145,000 in print by 2010, although digital subscriptions had risen to over 15,000. By 2021, the total for both print and digital combined was 96,000.[5]

History[edit]

Founding and journalistic roots[edit]

The Nation was established on July 6, 1865, at 130 Nassau Street ("Newspaper Row") in Manhattan. Its founding coincided with the closure of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator,[6] also in 1865, after slavery was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution; a group of abolitionists, led by the architect Frederick Law Olmsted, desired to found a new weekly political magazine. Edwin Lawrence Godkin, who had been considering starting such a magazine for some time, agreed and so became the first editor of The Nation.[7] Wendell Phillips Garrison, son of The Liberator's editor/publisher William Lloyd Garrison, was Literary Editor from 1865 to 1906.

Its founding publisher was Joseph H. Richards; the editor was Godkin, an immigrant from Ireland who had formerly worked as a correspondent of the London Daily News and The New York Times.[8][9] Godkin sought to establish what one sympathetic commentator later characterized as "an organ of opinion characterized in its utterance by breadth and deliberation, an organ which should identify itself with causes, and which should give its support to parties primarily as representative of these causes."[10]

In its "founding prospectus" the magazine wrote that the publication would have "seven main objects" with the first being "discussion of the topics of the day, and, above all, of legal, economical, and constitutional questions, with greater accuracy and moderation than are now to be found in the daily press."[11] The Nation pledged to "not be the organ of any party, sect or body" but rather to "make an earnest effort to bring to discussion of political and social questions a really critical spirit, and to wage war upon the vices of violence, exaggeration and misrepresentation by which so much of the political writing of the day is marred."[11]

In the first year of publication, one of the magazine's regular features was The South As It Is,[12] dispatches from a tour of the war-torn region by John Richard Dennett, a recent Harvard graduate and a veteran of the Port Royal Experiment. Dennett interviewed Confederate veterans, freed slaves, agents of the Freedmen's Bureau, and ordinary people he met by the side of the road.

Among the causes supported by the publication in its earliest days was civil service reform—moving the basis of government employment from a political patronage system to a professional bureaucracy based upon meritocracy.[10] The Nation also was preoccupied with the reestablishment of a sound national currency in the years after the American Civil War, arguing that a stable currency was necessary to restore the economic stability of the nation.[13] Closely related to this was the publication's advocacy of the elimination of protective tariffs in favor of lower prices of consumer goods associated with a free trade system.[14]

The magazine would stay at Newspaper Row for 90 years.

From 1880s literary supplement to 1930s New Deal booster[edit]

In 1881, newspaperman-turned-railroad-baron Henry Villard acquired The Nation and converted it into a weekly literary supplement for his daily newspaper the New York Evening Post. The offices of the magazine were moved to the Evening Post's headquarters at 210 Broadway. The New York Evening Post would later morph into a tabloid, the New York Post, a left-leaning afternoon tabloid, under owner Dorothy Schiff from 1939 to 1976. Since then, it has been a conservative tabloid owned by Rupert Murdoch, while The Nation became known for its left-wing ideology.[15]

In 1900, Henry Villard's son, Oswald Garrison Villard, inherited the magazine and the Evening Post, and sold off the latter in 1918. Thereafter, he remade The Nation into a current affairs publication and gave it an anti-classical liberal orientation. Oswald Villard welcomed the New Deal and supported the nationalization of industries – thus reversing the meaning of "liberalism" as the founders of The Nation would have understood the term, from a belief in a smaller and more restricted government to a belief in a larger and less restricted government.[16][17] Villard sold the magazine in 1935. Maurice Wertheim, the new owner, sold it in 1937 to Freda Kirchwey, who served as editor from 1933 to 1955.

Almost every editor of The Nation from Villard's time to the 1970s was looked at for "subversive" activities and ties.[18] When Albert Jay Nock published a column criticizing Samuel Gompers and trade unions for being complicit in the war machine of the First World War, The Nation was briefly suspended from the US mail.[19]

World War II and early Cold War[edit]

The magazine's financial problems in the early 1940s prompted Kirchwey to sell her individual ownership of the magazine in 1943, creating a nonprofit organization, Nation Associates, out of the money generated from a recruiting drive of sponsors. This organization was also responsible for academic affairs, including conducting research and organizing conferences, that had been a part of the early history of the magazine. Nation Associates became responsible for the operation and publication of the magazine on a nonprofit basis, with Kirchwey as both president of Nation Associates and editor of The Nation.[20]

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, The Nation repeatedly called on the United States to enter World War II to resist fascism, and after the US entered the war, the publication supported the American war effort.[21] It also supported the use of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.[21]

During the late 1940s and again in the early 1950s, a merger was discussed by Kirchwey (later Carey McWilliams) and The New Republic's Michael Straight. The two magazines were very similar at that time — both were left of center, The Nation further left than TNR; both had circulations around 100,000, although TNR's was slightly higher; and both lost money. It was thought that the two magazines could unite and make the most powerful journal of opinion. The new publication would have been called The Nation and New Republic. Kirchwey was the most hesitant, and both attempts to merge failed. The two magazines would later take very different paths: The Nation achieved a higher circulation, and The New Republic moved more to the right.[22]

In the 1950s, The Nation was attacked as "pro-communist" because of its advocacy of détente with the expansionist Soviet Union of Joseph Stalin, and its criticism of McCarthyism.[9] One of the magazine's writers, Louis Fischer, resigned from the magazine afterwards, claiming The Nation's foreign coverage was too pro-Soviet.[23] Despite this, Diana Trilling pointed out that Kirchwey did allow anti-Soviet writers, such as herself, to contribute material critical of Russia to the magazine's arts section.[24]

During McCarthyism (the Second Red Scare), The Nation was banned from several school libraries in New York City and Newark,[25] and a Bartlesville, Oklahoma, librarian, Ruth Brown, was fired from her job in 1950, after a citizens committee complained she had given shelf space to The Nation.[25]

In 1955, George C. Kirstein replaced Kirchway as magazine owner.[26] James J. Storrow Jr. bought the magazine from Kirstein in 1965.[27]

During the 1950s, Paul Blanshard, a former associate editor, served as The Nation's special correspondent in Uzbekistan. His most famous writing was a series of articles attacking the Catholic Church in America as a dangerous, powerful, and undemocratic institution.

1970s to 2022[edit]

In June 1979, The Nation's publisher Hamilton Fish and then-editor Victor Navasky moved the magazine to 72 Fifth Avenue, in Manhattan. In June 1998, the periodical had to move to make way for condominium development. The offices of The Nation are now at 33 Irving Place, in Manhattan's Gramercy Park neighborhood.

In 1977, a group organized by Hamilton Fish V bought the magazine from the Storrow family.[28] In 1985, he sold it to Arthur L. Carter, who had made a fortune as a founding partner of Carter, Berlind, Potoma & Weill.

In 1991, The Nation sued the Department of Defense for restricting free speech by limiting Gulf War coverage to press pools. However, the issue was found moot in Nation Magazine v. United States Department of Defense, because the war ended before the case was heard.

In 1995, Victor Navasky bought the magazine and, in 1996, became publisher. In 1995, Katrina vanden Heuvel succeeded Navasky as editor of The Nation, and in 2005, as publisher.

In 2015, The Nation celebrated its 150th anniversary with a documentary film by Academy Award-winning director Barbara Kopple; a 268-page special issue[29] featuring pieces of art and writing from the archives, and new essays by frequent contributors like Eric Foner, Noam Chomsky, E. L. Doctorow, Toni Morrison, Rebecca Solnit, and Vivian Gornick; a book-length history of the magazine by D. D. Guttenplan (which The Times Literary Supplement called "an affectionate and celebratory affair"); events across the country; and a relaunched website. In a tribute to The Nation, published in the anniversary issue, President Barack Obama said:

In an era of instant, 140-character news cycles and reflexive toeing of the party line, it's incredible to think of the 150-year history of The Nation. It's more than a magazine — it's a crucible of ideas forged in the time of Emancipation, tempered through depression and war and the civil-rights movement, and honed as sharp and relevant as ever in an age of breathtaking technological and economic change. Through it all, The Nation has exhibited that great American tradition of expanding our moral imaginations, stoking vigorous dissent, and simply taking the time to think through our country's challenges anew. If I agreed with everything written in any given issue of the magazine, it would only mean that you are not doing your jobs. But whether it is your commitment to a fair shot for working Americans, or equality for all Americans, it is heartening to know that an American institution dedicated to provocative, reasoned debate and reflection in pursuit of those ideals can continue to thrive.

On January 14, 2016, The Nation endorsed Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders for President. In their reasoning, the editors of The Nation professed that "Bernie Sanders and his supporters are bending the arc of history toward justice. Theirs is an insurgency, a possibility, and a dream that we proudly endorse."[30]

On June 15, 2019, Heuvel stepped down as editor; D. D. Guttenplan, the editor-at-large, took her place.[31]

On March 2, 2020, The Nation again endorsed Vermont United States Senate|Senator Bernie Sanders for President of the United States|President. In their reasoning, the editors of The Nation professed: "As we find ourselves on a hinge of history—a generation summoned to the task of redeeming our democracy and restoring our republic—no one ever has to wonder what Bernie Sanders stands for."[4]

On February 23, 2022, The Nation named Jacobin founder Bhaskar Sunkara its new president.[32] In December 2023, Sunkara announced the magazine would be switching from a biweekly format to a larger monthly publication.[33]

Finances[edit]

Print ad pages declined by 5% from 2009 to 2010, while digital advertising rose 32.8% from 2009 to 2010.[34] Advertising accounts for 10% of total revenue for the magazine, while circulation totals 60%.[35] The Nation has lost money in all but three or four years of operation and is sustained in part by a group of more than 30,000 donors called Nation Associates, who donate funds to the periodical above and beyond their annual subscription fees. This program accounts for 30% of the total revenue for the magazine. An annual cruise also generates $200,000 for the magazine.[35] Since late 2012, the Nation Associates program has been called Nation Builders.[36]

In 2023, the magazine had approximately 91,000 subscribers, roughly 80% of whom pay for the print magazine. Adding sales from newsstands, The Nation had a total circulation of 96,000 copies per issue in 2021, earning the majority of its revenue from subscriptions and donations, rather than print advertising.[33]

Poetry[edit]

Since its creation, The Nation has published significant works of American poetry,[37][38] including works by Hart Crane, Eli Siegel, Elizabeth Bishop, and Adrienne Rich,[37] as well as W.S. Merwin, Pablo Neruda, Denise Levertov, and Derek Walcott.[38]

In 2018, the magazine published a poem entitled "How-To" by Anders Carlson-Wee which was written in the voice of a homeless man and used black vernacular. This led to criticism from writers such as Roxane Gay because Carlson-Wee is white. The Nation's two poetry editors, Stephanie Burt and Carmen Giménez Smith, issued an apology for publishing the poem, the first such action ever taken by the magazine.[37] The apology itself became an object of criticism also. Poet and Nation columnist Katha Pollitt called the apology "craven" and likened it to a letter written from "a reeducation camp".[37] Grace Schulman, The Nation's poetry editor from 1971 to 2006, wrote that the apology represented a disturbing departure from the magazine's traditionally broad conception of artistic freedom.[38]

Regular columns[edit]

The magazine runs a number of regular columns:

- "Beneath the Radar" by Gary Younge

- "Deadline Poet" by Calvin Trillin

- "Diary of a Mad Law Professor" by Patricia J. Williams

- "The Liberal Media" by Eric Alterman

- "Subject to Debate" by Katha Pollitt

- "Between the Lines" by Laila Lalami

Regular columns in the past have included:

- "Look Out" by Naomi Klein

- "Sister Citizen" by Melissa Harris-Perry[39]

- "Beat the Devil" (1984–2012) by Alexander Cockburn

- "Dispatches" (1984–87) by Max Holland and Kai Bird[40]

- "Minority Report" (1982–2002) by Christopher Hitchens

- "The Nation cryptic crossword" by Frank W. Lewis from 1947 to 2009, and Joshua Kosman and Henri Picciotto from 2011 to 2020, that is now available by subscription[41]

See also[edit]

- Modern liberalism in the United States

- Harper & Row v. Nation Enterprises

- Nation Magazine v. United States Department of Defense

- Jacobin

- Mother Jones

References[edit]

- ^ "Masthead". The Nation. March 24, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ a b "About Us and Contact". The Nation. December 9, 2009. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ "The Nation Media Kit 2022" (PDF). The Nation. January 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ a b "'The Nation' Endorses Bernie Sanders and His Movement". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ "The Nation Media Kit 2022" (PDF). The Nation. January 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ The Anti-Slavery Reporter, August 1, 1865, p. 187.

- ^ Fettman, Eric (2009). "Godkin, E. L.". In Vaughn, Stephen L. (ed.). Encyclopedia of American Journalism. London: Routledge. p. 200. ISBN 9780415969505.

- ^ Moore, John Bassett (April 27, 1917). "Proceedings at the Semi-Centennial Dinner: The Biltmore, April 19, 1917". The Nation. 104 (2704). section 2, pp. 502–503.

- ^ a b Aucoin, James (2008). "The Nation". In Vaughn, Stephen L. (ed.). Encyclopedia of American Journalism. New York: Routledge. pp. 317–8. ISBN 978-0-415-96950-5.

- ^ a b Moore, "Proceedings at the Semi-Centennial Dinner", p. 503.

- ^ a b Richards, Joseph H. (July 6, 1865). "Founding Prospectus". The Nation. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015.

- ^ Dennett, John R. (2010). The South As It Is: 1865–1866. University of Alabama Press.

- ^ Moore, "Proceedings at the Semi-Centennial Dinner", pp. 503–504.

- ^ Moore, "Proceedings at the Semi-Centennial Dinner", p. 504.

- ^ Spike, Carlett (December 9, 2016). "'What's bad for the nation is good for The Nation'". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- ^ Carey McWilliams, "One Hundred Years of The Nation." Journalism Quarterly 42.2 (1965): 189–197.

- ^ Dollena Joy Humes, Oswald Garrison Villard: Liberal of the 1920s (Syracuse University Press, 1960).

- ^ Kimball, Penn (March 22, 1986). "The History of The Nation According to the FBI". The Nation: 399–426. ISSN 0027-8378.

- ^ Wreszin, Michael (1969). "Albert Jay Nock and the Anarchist Elitist Tradition in America". American Quarterly. 21 (2). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 173. doi:10.2307/2711573. JSTOR 2711573.

It was probably the only time any publication was suppressed in America for attacking a labor leader, but the suspension seemed to document Nock's charges.

- ^ Alpern, Sara (1987). Freda Kirchwey: A Woman of the Nation. President and Fellows of Harvard College. pp. 156–161. ISBN 0-674-31828-5.

- ^ a b Boller, Paul F. (c. 1992). "Hiroshima and the American Left". Memoirs of An Obscure Professor and Other Essays. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press. ISBN 0-87565-097-X.

- ^ Navasky, Victor S. (January 1, 1990). "The Merger that Wasn't". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378.

- ^ Alpern, Sara (1987). Freda Kirchwey, a Woman of the Nation. Boston: Harvard University Press. pp. 162–5. ISBN 0-674-31828-5.

- ^ Seaton, James (1996). Cultural Conservatism, Political Liberalism: From Criticism to Cultural Studies. University of Michigan Press. p. 71. ISBN 0-472-10645-7.

- ^ a b Caute, David (1978). The Great Fear: the Anti-Communist purge under Truman and Eisenhower. London: Secker and Warburg. p. 454. ISBN 0-436-09511-4.

- ^ "KIRCHWEY REGIME QUITS THE NATION; Weekly's Editor - Publisher Turns It Over to Carey McWilliams, G. C. Kirstein". The New York Times. September 15, 1955. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ Sibley, John (December 27, 1965). "NATION MAGAZINE SOLD TO PRODUCER; Storrow Taking Over Liberal Weekly From Kirstein for an Undisclosed Price POLICY TO BE RETAINED Staff Also Will Be Kept, New Owner Says -- First Editor Began in 1856". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ Carmody, Deirdre (December 23, 1977). "Nation Magazine Sold to Group Led by Hamilton Fish". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ "150th Anniversary Special Issue". The Nation. Archived from the original on July 6, 2015.

- ^ "Bernie Sanders for President". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ Hsu, Tiffany (April 8, 2019). "Katrina vanden Heuvel to Step Down as Editor of The Nation". The New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ "The Nation Names Bhaskar Sunkara its New President". The Nation. February 23, 2022. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ a b Dwyer, Kate (December 11, 2023). "The Nation Magazine to Become Monthly". The New York Times. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ Steve Cohn. "min Correction: The Nation Only Down Slightly in Print Ad Sales, Up in Web". MinOnline. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- ^ a b Peters, Jeremy W. Peters (November 8, 2010). "Bad News for Liberals May be Good News for a Liberal Magazine". The New York Times.

- ^ Katrina vanden Heuvel (December 28, 2012). "Introducing The Nation Builders". The Nation.

- ^ a b c d Jennifer Schuessler, A Poem in The Nation Spurs a Backlash and an Apology, New York Times (August 1, 2018).

- ^ a b c Grace Schulman, The Nation Magazine Betrays a Poet — and Itself, New York Times (August 6, 2018).

- ^ Melissa Harris-Perry. "Sister Citizen". The Nation. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- ^ Hiar, Corbin (April 24, 2009). "Kai Bird: The Nation's Foreign Editor". Hiar learning. Wordpress. Retrieved April 24, 2010.

- ^ "Out of Left Field Cryptics". leftfieldcryptics.com. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Pollak, Gustav (1915). Fifty years of American idealism: The New York Nation, 1865-1915. Brief history plus numerous essays.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- The Nation Archive (subscription required)

- The Nation (archive 1865–1925) at HathiTrust Digital Library (free)

- The Nation (archive 1984–2005) at The Free Library (free)