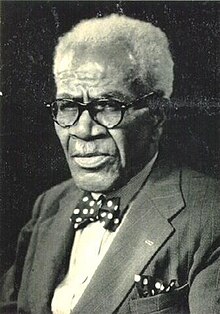

T.A. Marryshow

T. A. Marryshow | |

|---|---|

Theophilus Albert Marryshow | |

| Born | Theophilus Albert Maricheau 7 November 1887 |

| Died | 19 October 1958 (aged 70) Grenada |

| Nationality | Grenadian |

| Other names | Albert Marryshow; Teddy Marryshow; T. Albert Marryshow |

| Occupation(s) | Journalist; politician |

| Known for | Promotion of the West Indies Federation |

| Children | 17, inc. Julian Marryshow[1] |

Theophilus Albert Marryshow CBE (7 November 1887 – 19 October 1958), sometimes known as "Teddy" or "Albert", was a radical politician in Grenada and considered the father of the West Indies Federation.

Early life[edit]

Theophilus Albert Maricheau was born in Grenada on 7 November 1887, the son of a small-scale cocoa farmer who reportedly disappeared the day his son was baptised. His mother died in 1890, and then Maricheau was brought up by his godmother. He initially attended a Roman Catholic primary school and, subsequently, a Methodist School. In 1903, he took a job with William Galwey Donovan, who was a newspaper publisher and printer. His company produced radical newspapers, advocating representative government and a West Indian federation. Marryshow, who at an early stage Anglicised his surname, advanced rapidly from delivering newspapers to being a competent journalist. Donovan, who was half-Grenadian and half-Irish, was known as the "lion" due to his red hair. Marryshow took on many of his ideas. Donovan also taught him about journalism and Marryshow became sub-editor of the St. George's Chronicle and Grenada Gazette in 1908. At the same time, he became active in local politics.[2][3][4]

Early career[edit]

Together with C. F. P. Renwick, Marryshow established a new paper, The West Indian, which advocated a Federation of the West Indies. The first issue (1 January 1915) promised that it would be "an immediate and accurate chronicler of current events, an untrammelled advocate of popular rights, unhampered by chains of party prejudice, an unswerving educator of the people in their duties as subjects of the state and citizens of the world". Marryshow was an outspoken opponent of the apartheid regime in South Africa and confidently predicted independence for British African colonies. At the same time, he also campaigned for West Indians to fight in World War One and for the establishment of the British West Indies Regiment. He was presented to the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII, during his 1920 visit to Grenada as "Grenada's leading journalist".[4][5][6] However, according to Grenada's second prime minister, Maurice Bishop, it was more usual for the British to refer to him as "this dangerous radical".[7]

In 1918 he set up the Representative Government Association (RGA) in Grenada, which petitioned the British Government to introduce elected members to the Legislative Council. In 1921, he went to London at his own expense to argue his case and this led directly to the establishment of the Woods Commission, which visited the Caribbean in 1922 and recommended five elected members out of a total of 16 in the Legislative Council, to apply both in Grenada as well as in the other Windward Islands, the British Leeward Islands and Trinidad and Tobago. Marryshow himself was elected representative for the St George's constituency, a position he retained for 33 years. He continued to participate in various activities designed to promote a regional Federation, including the first regional conference on integration, held in Barbados in 1929. In the 1920s the ideas of Marcus Garvey, who preached the eventual return of Black Caribbean people to Africa, took hold in the Caribbean. To restrict their circulation the British passed a Seditious Publications Bill, which was opposed by Marryshow who believed strongly in the freedom of the press. He visited London again to lobby the British Colonial Office in favour of a Federation in 1931. A new constitution for Grenada was approved in 1935, adding additional elected representatives to the Legislative Council.[3][4][7][8][9]

Later career[edit]

Marryshow co-founded the Grenada Workingmen’s Association in 1931 and in 1945 was appointed as the first president of the Caribbean Labour Congress, the first attempt to bring together regional labour unions. For reasons of ill-health, he sold The West Indian newspaper in 1934. His financial situation was also poor and would remain so until his death. Towards the end of his political career, the status quo in Grenada was challenged by the more populist politics of Eric Gairy, who would go on to become the country’s first prime minister. In the first election under full adult suffrage in 1951, Marryshow retained his seat, but Gairy's party took six of the eight available. However, Marryshow was made Deputy President of the Legislative Council.[3][10]

In June 1953, he was invited to the Coronation of Elizabeth II in London, and celebrated her visit to Jamaica as a "dream come true", to have a reigning Sovereign visit the Caribbean.[11] Having thus made the transformation from being a rebel to almost an establishment figure, Marryshow continued to work towards the establishment of a West Indies Federation, which eventually started in 1958 and which he described as his dream come true. He was nominated to represent Grenada as a Senator in the Upper House of the Federation's Parliament. He died in the same year and thus did not live to see the collapse of his dreams; the Federation was dissolved after just four years, in 1962.[3][4][6][7][9]

Death and heritage[edit]

Marryshow died on 19 October 1958, aged 70. He had never married but fathered 17 children, including six with Edna Gittens.[1] His large house in St George's, Grenada, now known as "Marryshow House", hosts the Grenada Centre of the School of Continuing Studies of the University of the West Indies. Although far from wealthy he managed, when he was 30, to build a substantial house, which overlooks St George’s Harbour. He named it the "Rosery" as there was a popular song by that name when it was being built, and he went on to develop an impressive rose garden. The house, which was reputedly the first built in Grenada using cast concrete, was in a colonial style and was idiosyncratically and eclectically furnished, with people remembering best a life-sized ceramic bulldog, which became his political mascot. He would take it to political meetings, and encourage people to use the name of "The Bulldog" for him. The dining room was frequently used to host the many people Marryshow had become friendly with through his work, including the Trinidadian writer C. L. R. James and the singer Paul Robeson. Marryshow was himself a good singer and enjoyed singing Spirituals. Since being sold by Marryshow’s family the building has hosted many important events and has also been twice featured on postage stamps of Grenada.[12]

In the Caribbean he became known as the "Father of the Federation" while in Britain he was known as "The Elder Statesman of the Caribbean". In 1974 he was remembered at a "Marryshow Festival", with an exhibition of his achievements held in his former house. At the beginning of the 1980s schoolchildren in Guyana were still using Colonial-era textbooks showing illustrations of white children in English homes. A new series of primary-school textbooks was developed and these were called "Marryshow Readers". In 2010, the Government of Grenada officially recognised 7 November as Marryshow Day, in recognition of his contribution to Grenada and the region. It had been unofficially celebrated for many years before that.[13] He also gave his name to the T.A. Marryshow Community College, which provides tertiary education in Grenada.[3][5][6][8]

Honours and awards[edit]

Marryshow was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 1943 Birthday Honours.

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Obituary for Basil Albert Marryshow". Grenadian Connection. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ^ Cox, Edward L. (February 2007). "William Galwey Donovan and the Struggle for Political Change in Grenada, 1883–1920". Small Axe. Project Muse. pp. 17–38. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Theophilus Albert Marryshow, CBE Father of West Indies Federation". Caribbean Elections Biography. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d "T.A. Marryshow". University of West Indies. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Theophilus Albert Marryshow The Father of Federation". Grenada Cultural Foundation. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Sheppard, Jill (1957). Marryshow of Grenada: An Introduction. Grenada: Letchworth Press. p. 56.

- ^ a b c Bishop, Maurice. "Address on Marryshow Day, 7 November 1982". Grenada Revolution Online. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ a b Schoenhals, Kai; Melanson, Richard (2019). Revolution And Intervention In Grenada: The New Jewel Movement, The United States, And The Caribbean. Routledge. ISBN 9780367285951. First published 1985.

- ^ a b King, Nelson A. (2 June 2015). "Father of West Indies Federation". Caribbean Life. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ Gunson, Phil; Chamberlain, Greg; Thompson, Andrew (2015). The Dictionary of Contemporary Politics of Central America and the Caribbean. Routledge. p. 397.

- ^ "The Queen is Passing By". Marryshow.name. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ Steele, Beverley A. "Marryshow House — A Living Legacy". University of West Indies. Retrieved 26 June 2020. (Based upon a paper originally written in 1992 and published in the Caribbean Quarterly, vol. 41, 1995.)

- ^ "Government officially recognises Marryshow Day". Spiceislander.com. 5 November 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2020.