Zona Sur

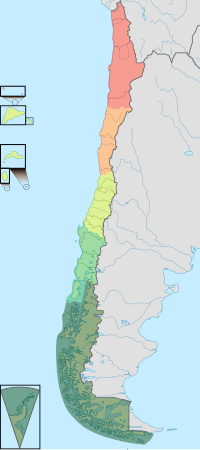

Zona Sur (Southern Zone) is one of the five natural regions on which CORFO divided continental Chile in 1950. Its northern border is formed by the Bío-Bío River, which separates it from the Central Chile Zone. The Southern Zone borders the Pacific Ocean to the west, and to the east lies the Andean mountains and Argentina. Its southern border is the Chacao Channel, which forms the boundary with the Austral Zone. While the Chiloé Archipelago belongs geographically to the Austral Zone in terms of culture and history, it lies closer to the Southern Zone.

Geography[edit]

Although many lakes can be found in the Andean and coastal regions of central Chile, the south (Sur de Chile) has the country's most lakes. Southern Chile stretches from below the Río Bío-Bío at about 37° south latitude to below Isla de Chiloé at about 43.4° south latitude. In this lake district of Chile, the valley between the Andes and the coastal range is closer to sea level, and the hundreds of rivers that descend from the Andes form lakes, some quite large, as they reach the lower elevations. They drain into the ocean through other rivers, some of which (principally the Calle-Calle River, which flows by the city of Valdivia) are the only ones in the whole country that are navigable for any stretch. The Central Valley's southernmost portion is submerged in the ocean and forms the Golfo de Ancud. Isla de Chiloé, with its rolling hills, is the last important elevation of the coastal range of mountains.

The lakes in this region are remarkably beautiful. The snow-covered Andes form a backdrop to clear blue or even turquoise waters, as at Lago Todos los Santos. The rivers that descend from the Andes rush over volcanic rocks, forming numerous white-water sections and waterfalls. Some sections still consist of old-growth forests, and in all seasons, but especially in the spring and summer, there are plenty of wildflowers and flowering trees. The pastures in the northernmost section, around Osorno, are well suited for raising cattle; milk, cheese, and butter are important products of that area. All kinds of berries grow in the area, some of which are exported, and freshwater farming of various species of trout and salmon has developed, with cultivators taking advantage of the abundant supply of clear running water. The lumber industry is also important. A number of tourists, mainly Chileans and Argentines, visit the area during the summer.

In terms of tectonics at Zona Sur the South American Plate is experiencing a long-term ENE-WSW shortening. This shortening is accommodated by strike-slip faults.[1] The details of this pattern show significant local variations.[1]

Climate[edit]

The climate of Southern Chile is rainy with a Mediterranean precipitation pattern.[2] The windward slopes of the Chilean Coast Range and the Andes receive up to 3000–5000 mm of precipitation annually.[2] Behind the Chilean Coast range there is a weak rain shadow while behind the Andes, in Argentina, precipitation drops sharply.[2] The zone lies in the mid-latitudes and is strongly influenced by the Westerlies.[2] During the summer the South Pacific High moves into the area.[2]

Soils[edit]

The main agricultural soils are; red clay soil (rojo arcillosos, ultisols), trumao and ñadi.[3] Some red clay soils are planted with Eucalyptus globulus.[4] In the middle course of Bío Bío River, in the northern part of Zona Sur, soils are sandy with a coarsening trend towards the Andes.[5] Soils of the Chilean Coast Range are mostly derived from metamorphic rock.[6] These soils are usually poor in phosphorus, potassium and have toxic levels of aluminium. Often, these soils have poor drainage and their thickness is highly variable even at scale of tens of meters.[6]

Flora and fauna[edit]

The natural vegetation of Southern Chile is mainly the Valdivian temperate rainforests. These forests are characterized by large trees, chiefly evergreen Nothofagus and Conifers plus Myrtles.[2][7] The understory is made of vines, hanging vines, bushes, small trees, moss, dead trunks and decomposing matter.[7] Despite being largely evergreen the Valdivian temperate rainforests do contain a number of deciduous tree species like Nothofagus obliqua and Nothofagus alpina.[2] Other vegetations types of southern Chile include Fitzroya forests, Araucaria forests and wetlands called ñadis.[7]

A number of small mammals inhabit Southern Chile including the pudú, coypu and Darwin's fox.[7][8]

History[edit]

At the time of the Spanish arrival beans, maize and potatoes are known to have been cultivated in Valdivia and around Bueno River.[9] The cultivation of beans extended likely all the way south to Chiloé Archipelago.[9]

Southern Chile was during the time of Spanish conquest and colony populated by indigenous Mapuches from Toltén River northwards and by Huilliches south of the river, both groups are classified as Araucanian. The mountainous zones in the east were populated by Pehuenches Puelches. Until the Battle of Curalaba and the following Destruction of Seven Cities around 1600 the southern zone was part of the General Captaincy of Chile and Spanish Empire. After 1600, the Spanish settlements were destroyed or abandoned with the exception of Valdivia that was re-founded in 1645 with heavy fortifications. The zone between Valdivia and Chiloé was gradually incorporated into Chile by a series of agreements with local Huilliches and founding of settlements. By 1850, this process was culminated with the immigration of thousands of German immigrants to Valdivia, Osorno and Llanquihue. The zone north of Valdivia was incorporated into Chile in the 1880s during the occupation of the Araucania.

Demographics[edit]

Spanish is widely spoken in all the region, but the southern people speak a bit slower than Santiaguinos. In the Araucanía region, the Mapudungun is used in rural communities, especially between elders. German is widely spoken in the region because of German colonization, but mostly as a second or third language.

Gallery[edit]

-

Cattle grazing in the Rupanco area.

-

Cattle grazing near Llanquihue Lake. Osorno Volcano in the background.

-

Haverbeck Canal

-

The maritime influence of some southern Andean valleys makes them prone to snow falls in winter such as in Curarrehue in the picture.

-

Calle-Calle River in picture is one of various large rivers that drain the Andean lakes of Zona Sur.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Sielfeld, Gerd; Lange, Dietrich; Cembrano, José (2019-02-12). "Intra‐Arc Crustal Seismicity: Seismotectonic Implicationsfor the Southern Andes Volcanic Zone, Chile" (PDF). Tectonics. 38 (2): 552–578. Bibcode:2019Tecto..38..552S. doi:10.1029/2018TC004985. S2CID 135109592.

- ^ a b c d e f g Veblen, Thomas T.; Donoso, Claudio; Kitzberger, Thomas; Rebertus, Alan J. (1996), "Ecology of Southern Chilean and Argentinean Nothofagus Forests", in Veblen, Thomas T.; Hill, Robert S.; Read, Jennifer (eds.), The Ecology and Biogeography of Nothofagus Forests, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-06423-3

- ^ Estudio de suelos de la provincia de Valdivia (in Spanish). Santiago: Instituto Nacional de Investigación de Recursos Naturales – Universidad Austral de Chile. 1978. p. 1.

- ^ Geldres, Edith; Schlatter, Juan E. (2004). "Crecimiento de las plantaciones de Eucalyptus globulussobre suelos rojo arcillosos de la provinciad Osorno, Décima Región" [Growth of Eucalyptus globulus plantations on red clay soils in the Province of Osorno, 10th Region, Chile] (PDF). Bosque (in Spanish). 25 (1): 95–101. doi:10.4067/S0717-92002004000100008. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- ^ Schlatter et al. 2003, p. 100.

- ^ a b Schlatter et al. 2003, pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b c d Hernández, Silvia (1973), Geografía de plantas y animales de Chile (in Spanish) (2nd ed.), Santiago de Chile: Editorial Universitaria, pp. 130–165

- ^ Silva-Rodríguez, E; Farias, A.; Moreira-Arce, D.; Cabello, J.; Hidalgo-Hermoso, E.; Lucherini, M. & Jiménez, J. (2016) [errata version of 2016 assessment]. "Lycalopex fulvipes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T41586A107263066. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41586A85370871.en. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ a b Pardo B., Oriana; Pizarro, José Luis (2014). Chile: Plantas alimentarias Prehispánicas (in Spanish) (2015 ed.). Arica, Chile: Ediciones Parina. p. 162. ISBN 9789569120022.

- Bibliography

- Schlatter, Juan; Grez, Renato; Gerding, Víctor (2003). Manual para el reconocimiento de suelos (in Spanish). Valdivia: Universidad Austral de Chile. ISBN 956-7105-25-1.