Politics of Solomon Islands

|

|---|

Politics of Solomon Islands takes place within the framework of a parliamentary representative democratic, constitutional monarchy. Solomon Islands is an independent Commonwealth realm, where executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and a multi-party parliament.

The head of state, the King or Queen of Solomon Islands, is represented by the Governor-General. The head of government is the Prime Minister. Constitutional safeguards include freedom of speech, press, worship, movement, and association. The Judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature.

Executive branch[edit]

The King of Solomon Islands is represented in Solomon Islands by a governor general who acts on the advice of the prime minister and the cabinet. The Governor-General of Solomon Islands is elected by parliament.

Solomon Islands governments are characterized by weak political parties and highly unstable parliamentary coalitions. They are subject to frequent votes of no confidence, and government leadership changes frequently as a result. Cabinet changes are common.

The Prime Minister, elected by Parliament, chooses the other members of the cabinet. Each ministry is headed by a cabinet member, who is assisted by a permanent secretary, a career public servant, who directs the staff of the ministry. The cabinet consists of the Prime Minister and ministers of executive departments. They answer politically to the House of Assembly.

Attorney General of Solomon Islands[edit]

As described in the Constitution of Solomon Islands (1978), the Attorney General is appointed by the Judicial and Legal Service Commission and acts as the principal legal adviser to the Government. The Attorney General of Solomon Islands may serve in an advisory capacity to the parliament, but does not possess any voting rights.[1]

| Name | Term |

|---|---|

| Francis Lenton Daly[2][3] | c. 1979-1980 |

| Frank Kabui[4] (1st Solomon Islander male) | c. 1980-1994 |

| Primo Afeau[5][6][7][8] | c. 1995-2006 |

| Julian Moti[9] | c. 2006-2007 |

| Nuatali Tongarutu (Acting)[10] | c. 2006-2007 |

| Gabriel Suri[11][12] (Acting; Permanent) | c. 2008-2010 |

| Billy Titulu[12][13] | c. 2010-2015 |

| James Apaniai[14] | c. 2015-2018 |

| Gilbert John Osmond Muria[15] | c. 2018- |

Solicitor General of Solomon Islands[edit]

The Solicitor General of Solomon Islands is the law officer that is below the Attorney General of Solomon Islands.

| Name | Term |

|---|---|

| Ranjit Hewagama[16] | c. 1998-2001 |

| Nathan Moshinsky[17] | c. 2003-2006 |

| Reginald Teutao[18][19] | c. 2007-2010 |

| Savenaca Banuve[20][21] | c. 2011-2023 |

Ministry of Justice and Legal Affairs[edit]

See Ministry of Justice and Legal Affairs (Solomon Islands)

Legislative branch[edit]

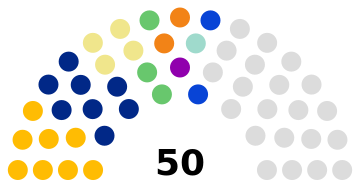

The National Parliament has 50 members, elected for a four-year term in single-seat constituencies. Solomon Islands have a multi-party system, with numerous parties in which no one party often has a chance of gaining power alone. Political parties must work with each other to form coalition governments.

Parliament may be dissolved by a majority vote of its members before the completion of its term. Parliamentary representation is based on single-member constituencies. Suffrage is universal for citizens over age 18.

Cabinet and ministries[edit]

Judiciary[edit]

The Governor General appoints the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court on the advice of the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition. The Governor General appoints the other justices with the advice of a judicial commission.

Political parties and elections[edit]

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | |

| Solomon Islands Democratic Party | 42,245 | 13.64 | 8 | New | |

| Solomon Islands United Party | 32,302 | 10.43 | 2 | New | |

| Kadere Party | 29,426 | 9.50 | 8 | +7 | |

| United Democratic Party | 25,295 | 8.17 | 4 | –1 | |

| Democratic Alliance Party | 19,720 | 6.37 | 3 | –4 | |

| People's Alliance Party | 18,573 | 6.00 | 2 | –1 | |

| People First Party | 11,419 | 3.69 | 1 | 0 | |

| Solomon Islands Party for Rural Advancement | 9,878 | 3.19 | 1 | 0 | |

| National Transformation Party | 4,622 | 1.49 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pan Melanesian Congress Party | 1,514 | 0.49 | 0 | 0 | |

| Green Party Solomon Islands | 619 | 0.20 | 0 | New | |

| New Nation Party | 593 | 0.19 | 0 | 0 | |

| Peoples Progressive Party | 381 | 0.12 | 0 | 0 | |

| Independents | 113,178 | 36.54 | 21 | –11 | |

| Total | 309,765 | 100.00 | 50 | 0 | |

| Valid votes | 309,765 | 99.71 | |||

| Invalid/blank votes | 902 | 0.29 | |||

| Total votes | 310,667 | 100.00 | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 359,523 | 86.41 | |||

| Source: Solomon Islands Election Resources | |||||

Administrative divisions[edit]

For local government, the country is divided into 10 administrative areas, of which nine are provinces administered by elected provincial assemblies, and the 10th is the city of Honiara, administered by the Honiara City Council.

Political history[edit]

Solomon Islands governments are characterized by weak political parties and highly unstable parliamentary coalitions. They are subject to frequent votes of no confidence, and government leadership changes frequently as a result. Cabinet changes are common.

The first post-independence government was elected in August 1980. Prime Minister Peter Kenilorea was head of government until September 1981, when he was succeeded by Solomon Mamaloni as the result of a realignment within the parliamentary coalitions. Following the November 1984 elections, Kenilorea was again elected Prime Minister, to be replaced in 1986 by his former deputy Ezekiel Alebua following shifts within the parliamentary coalitions. The next election, held in early 1989, returned Solomon Mamaloni as Prime Minister. Francis Billy Hilly was elected Prime Minister following the national elections in June 1993, and headed the government until November 1994 when four Cabinet Ministers were allegedly bribed by a foreign logging company to shift their parliamentary loyalties and bring Solomon Mamaloni back to power.[22][23]

The national election of 6 August 1997 resulted in Bartholomew Ulufa'alu's election as Prime Minister, heading a coalition government, which christened itself the Solomon Islands Alliance for Change. In June 2000, an insurrection mounted by militants from the island of Malaita resulted in the brief detention of Ulufa’alu and his subsequent forced resignation. Prior to this Ulufa'alu had requested Australian intervention to stabilise the deteriorating situation in Solomon Islands, which was refused. Manasseh Sogavare, leader of the People's Progressive Party, was chosen Prime Minister by a loose coalition of parties. New elections in December 2001 brought Sir Allan Kemakeza into the Prime Minister's chair with the support of a coalition of parties. Bartholomew Ulufa’alu was Leader of the Opposition.

Kemakeza attempted to address the deteriorating law and order situation in the country, but the prevailing atmosphere of lawlessness, widespread extortion, and ineffective police prompted a formal request by the Solomon Islands Government for outside help. In July 2003, Australian and Pacific Island police and troops arrived in the Solomon Islands under the auspices of the Australian-led Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI). The mission, consisting of a policing effort, military support, and a large development component, largely restored law and order to Honiara and the other provinces of Solomon Islands. Efforts are now underway to identify a donor base and reestablish credible systems of governance and financial management.

In the 2006 legislative election Kemakeza's People's Alliance Party suffered a major defeat, losing more than half its seats. However Deputy Prime Minister Synder Rini succeeded in gaining the support of enough Independent Members of Parliament to form government. This resulted in rioting in the capital of Honiara. Much of the violence was directed at Chinese businessmen who were accused of influencing the election result. Reinforcements to RAMSI stabilised the situation, but not before serious damage was done to the nation's already fragile economy. Rini resigned shortly before a motion of no confidence was due to take place, and was succeeded by Manasseh Sogavare, a former Prime Minister.

The inability of RAMSI to oversee a peaceful election has raised serious doubts about the success of the mission.

In 2006, riots broke out following the election of Snyder Rini as Prime Minister, destroying part of Chinatown and displacing more than 1,000 Chinese residents; the large Pacific Casino Hotel was also totally gutted.[24] The commercial heart of Honiara was virtually reduced to rubble and ashes.[25] Three National Parliament members, Charles Dausabea, Nelson Ne'e, and Patrick Vahoe,[26] were arrested during or as a result of the riots. The Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI), the 16-country Pacific Islands Forum initiative set up in 2003 with assistance from Australia, intervened, sending in additional police and army officers to bring the situation under control. A vote of no confidence was passed against the Prime Minister. Following his resignation, a five-party Grand Coalition for Change Government was formed in May 2006, with Manasseh Sogavare as Prime Minister, quelling the riots and running the government. The military part of RAMSI was withdrawn in 2013 and rebuilding took shape.[27]

In 2009, the government is scheduled to set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, with the assistance of South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, to "address people’s traumatic experiences during the five-year ethnic conflict on Guadalcanal".[28][29]

The government continues to face serious problems, including an uncertain economic outlook, deforestation, and malaria control. At one point, prior to the deployment of RAMSI forces, the country was facing a serious financial crisis. While economic conditions are improving, the situation remains unstable.

In 2006, riots broke out following the election of Snyder Rini as Prime Minister, destroying part of Chinatown and displacing more than 1,000 Chinese residents; the large Pacific Casino Hotel was also totally gutted.[24] The commercial heart of Honiara was virtually reduced to rubble and ashes.[30] Three National Parliament members, Charles Dausabea, Nelson Ne'e, and Patrick Vahoe,[31] were arrested during or as a result of the riots. The Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI), the 16-country Pacific Islands Forum initiative set up in 2003 with assistance from Australia, intervened, sending in additional police and army officers to bring the situation under control. A vote of no confidence was passed against the Prime Minister. Following his resignation, a five-party Grand Coalition for Change Government was formed in May 2006, with Manasseh Sogavare as Prime Minister, quelling the riots and running the government. The military part of RAMSI was withdrawn in 2013 and rebuilding took shape.[27]

In 2009, the government is scheduled to set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, with the assistance of South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, to "address people’s traumatic experiences during the five-year ethnic conflict on Guadalcanal".[28][32]

The government continues to face serious problems, including an uncertain economic outlook, deforestation, and malaria control. At one point, prior to the deployment of RAMSI forces, the country was facing a serious financial crisis. While economic conditions are improving, the situation remains unstable.

2021 unrest[edit]

In 2019, the central government under Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare withdrew recognition of the Republic of China (Taiwan) and established relations with the mainland People's Republic of China. Malaita Province, however, continued to be supported by Taiwan and the United States, the latter sending US$25 million of aid to the island in 2020.[33] The premier of Malaita Province, Daniel Suidani, also held an independence referendum in 2020 which the national government has dismissed as illegitimate.[34] Rising unemployment and poverty, worsened by the border closure during the COVID-19 pandemic, have also been cited as a cause of the unrest.[35] Chinese businesses were also accused of giving jobs to foreigners instead of locals.[36]

The protests were initially peaceful,[12] but turned violent on 24 November 2021 after buildings adjoining the Solomon Islands Parliament Building[37] were burnt down. Schools and businesses were closed down as police and government forces clashed with protesters. Violence escalated as Honiara's Chinatown was looted.[38][39] Most of the protesters came from Malaita Province.[40][41]

Australia responded to the unrest by deploying Australian Federal Police and Australian Defence Force personnel following a request from the Sogavare government under the Australia–Solomon Islands Bilateral Security Treaty.[42] Papua New Guinea, Fiji and New Zealand also sent peacekeepers.[43][44]

Since 2024[edit]

In May 2024, Jeremiah Manel was elected as the Solomon Islands new prime minister to succeed Manasseh Sogavare.[45]

Land ownership[edit]

Land ownership is reserved for Solomon Islanders. At the time of independence, citizenship was granted to all persons whose parents are or were both British protected persons and members of a group, tribe, or line indigenous to Solomon Islands. The law provides that resident expatriates, such as the Chinese and Kiribati, may obtain citizenship through naturalization.

Land generally is held on a family or village basis and may be handed down from mother or father according to local custom. The islanders are reluctant to provide land for nontraditional economic undertakings, and this has resulted in continual disputes over land ownership.

Military[edit]

No military forces are maintained by Solomon Islands, although the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force (RSIP) of nearly 500 includes a border protection element. The police also have responsibility for fire service, disaster relief, and maritime surveillance. The police force is headed by a commissioner, appointed by the Governor General and responsible to the prime minister.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Constitution 1978". www.paclii.org. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Loading site please wait..." www.sclqld.org.au. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "DISTRICT COURT OF QUEENSLAND ANNUAL REPORT 1998-1999" (PDF).

- ^ "Mr Frank Kabui is elected new Governor-General designate of Solomon Islands | National Parliament of Solomon Islands". www.parliament.gov.sb. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Solomon Islands - Legislation - Chronological Index". www.paclii.org. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Prime Minister v Governor-General [1998] SBHC 41; HC-CC 150 of 1998 (10 September 1998) / HIGH COURT OF SOLOMON ISLANDS / HC-CC150 of 1998 / THE PRIME MINISTER -V THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2012.

- ^ "Solomons attorney general to be removed - report". Radio New Zealand. 21 August 2006. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Pacific News (8 Australian Law Librarian 2000)". heinonline.org. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Julian Moti and the raid on the Prime Minister's office". Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability. 19 December 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Solomons erratic on fugitive lawyer visit". amp.smh.com.au. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ "SOLOMONS NAME SURI AS NEW ATTORNEY GENERAL | Pacific Islands Report". www.pireport.org. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ a b c "Solomon Islands appoints new Attorney general". pina.com.fj. 9 September 2010. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018. Cite error: The named reference ":0" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Solomon Islands attorney general says teachers shouldn't sue". Radio New Zealand. 4 March 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "New AG for Solomon Islands". Radio New Zealand. 26 June 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "SIPEU commends new Attorney General". Island Sun. 14 November 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Borda, Aldo Zammit (31 October 2013). Legislative Drafting. Routledge. ISBN 9781317983033.

- ^ "Solomons Solicitor General leaves post early". Radio New Zealand. 22 October 2006. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "SOLOMONS GOVERNOR GENERAL SEEKS PARLIAMENT SESSION | Pacific Islands Report". www.pireport.org. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "Former Solomons Cabinet Ministers told they can hold on to their government cars". Radio New Zealand. 14 February 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ "PILON COUNTRY REPORT 2011 / SOLOMON ISLANDS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 March 2018.

- ^ "The Mid-term review of the Solomon Islands Justice Program" (PDF). August 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2018.

- ^ "page 32".

- ^ http://www.native-net.org/archive/nl/9512/0134.html[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Spiller, Penny (21 April 2006). "Riots highlight Chinese tensions". BBC News. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ Huisken, Ron; Thatcher, Meredith (2007). History as Policy: Framing the debate on the future of Australia's defence policy. ANU E Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-921313-56-1.

- ^ "Third Solomons MP arrested over riot". The Sydney Morning Herald. 24 April 2006. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Doing Business in the Solomon Islands" (PDF). pitic.org.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Solomon Islands moves closer to establishing truth and reconciliation commission". Radio New Zealand International. 4 September 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ "Archbishop Tutu to Visit Solomon Islands", Solomon Times, 4 February 2009

- ^ Huisken, Ron; Thatcher, Meredith (2007). History as Policy: Framing the debate on the future of Australia's defence policy. ANU E Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-921313-56-1.

- ^ "Third Solomons MP arrested over riot". The Sydney Morning Herald. 24 April 2006. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ "Archbishop Tutu to Visit Solomon Islands", Solomon Times, 4 February 2009

- ^ "China convinced the Solomons to switch allegiances. Its one rebel province is now in line for $35m in US aid". ABC News. 15 October 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ Kaye, Ron; Packham, Colin (25 November 2021). "Australia to deploy police, military to Solomon Islands as protests spread". Reuters. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "Three killed in Solomon Islands unrest, burnt bodies found in Chinatown". South China Morning Post. 27 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ "Solomon Islands violence recedes but not underlying tension". AP NEWS. 26 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ Lagan, Bernard. "Solomon Islands protesters burn parliament and Chinese shops in anti-Beijing riots". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ "Solomon Islands: Australia sends peacekeeping troops amid riots". BBC News. 25 November 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ "Australia sending troops to Solomon Islands as protests spread". CBC News.

- ^ McGuirk, David Rising and Rod (25 November 2021). "Australia sending troops, police to Solomon Islands amid unrest". CTV News. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ "Australia sends troops and police to Solomon Islands as unrest grows". The Guardian. 25 November 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ Andrews, Karen (25 November 2021). "Joint media release - Solomon Islands" (Press release). Canberra: Australian Government. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "Riots rock Solomon Islands capital for third day despite peacekeepers". Agence France-Presse. 26 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021 – via France 24.

- ^ "Fiji sends 50 peacekeepers to Solomon Islands". the Guardian. 29 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Solomon Islands elects ex-top diplomat as new prime minister". Al Jazeera.

External links[edit]

- Parliament of Solomon Islands

- Office of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Constitutional Reform Unit

- Office of the Auditor General

- Central Bank of Solomon Islands

- Ministry of Commerce, Industry, Labour and Immigration

- Department of External Trade

- Ministry of Mines and Energy