Bellaire Goblet Company

| Industry | Glass manufacturing |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1876 |

| Founder | E. G. Morgan, C. H. Over, Henry Carr, John Robinson, M. L. Blackburn, and W. A. Gorby |

| Defunct | 1891 |

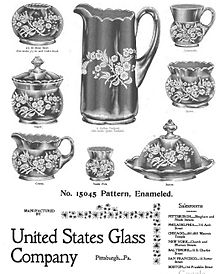

| Successor | Factory M of U.S. Glass Company (closed 1893) |

| Headquarters | Bellaire, Ohio 1876-1888; Findlay, Ohio 1888-1891 |

Key people | John Robinson, Charles Henry Over |

| Products | goblets, tableware |

Number of employees | 312 (1888) |

The Bellaire Goblet Company was the largest manufacturer of goblets (glass stemware) in the United States during the 1880s. Its original glass plant was located in Bellaire, Ohio, which earned the nickname "Glass City" because of its many glass factories. Bellaire Goblet Company was part of Ohio's "Glass City" on the east side of the state, and later moved to the other side of the state to participate in Northwest Ohio's "Gas Boom". It also became part of a large glass trust.

The company was incorporated on July 31, 1876, by experienced glass makers from the Belmont Glass Company, which was Bellaire's first glass manufacturer. Operations for Bellaire Goblet started later in the year. By 1879 the company was exporting goods to Europe, South America, and Australia, and it expanded production capacity by leasing an additional glass works in town. Bellaire had what glass companies and other manufacturers needed: a good transportation infrastructure, a good labor supply, and plenty of coal for fuel.

In 1886 Northwest Ohio began a "gas boom" with the discovery of natural gas near the small community of Findlay. Local businessmen used incentives such as free land, cash, and low-cost natural gas to lure energy–intensive manufacturers to set up operations there. Bellaire Goblet Company moved to Findlay in 1888. The company kept the name "Bellaire" because of the brand recognition already associated with that name. During the next few years Northwest Ohio began having gas shortages in addition to the country's economic recession, and this put financial hardship on companies that relied on large quantities of fuel for their manufacturing process. In 1891 Bellaire Goblet Company was sold to a glass trust named United States Glass Company and became known as the trust's "Factory M". The Factory M plant was closed permanently in January 1893 when it had no fuel for its furnaces after the town stopped providing natural gas. The plant was sold to a non–glass company in 1894.

Background[edit]

Glass is made by starting with a batch of ingredients, melting it together, forming the glass product, and gradually cooling it. The batch of ingredients is dominated by sand, which contains silica.[1] The batch is placed inside a pot or tank that is heated by a furnace to roughly 3090 °F (1700 °C).[1] The melted batch is typically shaped into the glass product (other than plate and window glass) by either a blowing or pressing it into a mold.[2] The glass product must then be cooled gradually (annealed), or else it could easily break.[3] An oven used for annealing is called a lehr.[4]

Because most glass plants melted their ingredients in a pot during the 1880s, the plant's number of pots was often used to describe a plant's capacity.[Note 1] One of the major expenses for the glass factories is fuel for the furnace.[6] Wood and coal have long been used as fuel for glassmaking. An alternative fuel, natural gas, became a desirable fuel for making glass because it is clean, gives a uniform heat, is easier to control, and melts the batch of ingredients faster.[7]

Glass City[edit]

Belmont County, Ohio, is located in the Ohio coal belt on the eastern side of the state.[8] One of the county's Ohio River communities is Bellaire. At one time, steamships traveling down the Ohio River knew Bellaire as the last stop for coal until Cincinnati.[9] Bellaire had ten coal mines in the hills adjacent to the town.[10] An 1873 map shows the Central Ohio Railroad entering Bellaire from the west, and the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad entering Bellaire from the north.[11] The Central Ohio Railroad was Bellaire's first, and it connected Bellaire with Columbus, Ohio. The line began being operated by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in 1865. The Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad eventually became controlled by the Pennsylvania Railroad.[12] In addition to its railroads, the National Road ran through Bellaire.[13] A few miles upriver was the city of Wheeling, West Virginia, which was an early glass producing center in what was at that time, the American "west". Glass was first made in Wheeling in the 1820s, and one of the larger glass works in the United States, J. H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company, was still operating there in the 1880s.[14]

Given Bellaire's transportation resources, fuel resource, and experienced workforce nearby, the town was an excellent location for a glass manufacturing plant. The Belmont Glass Company, founded in 1866, was Bellaire's first of many glass plants and the second in Belmont County.[15] For the period of 1870 to 1885, Bellaire's nickname was "Glass City" because of its numerous glass factories and the large amount of capital invested in them.[16] By 1880, Belmont County ranked sixth in the value of glass produced among the nation's counties, and the state of Ohio ranked fourth.[17] Glass manufacturers inspected in Bellaire in 1888 (includes makers of bottles, fruit jars, glassware, lantern globes and window glass) were: Rodefer Brothers, Aetna Glass Manufacturing, Bellaire Fruit Jar, Union Window Glass Works, Crystal Window Glass, Lantern Globe, Bellaire Bottle, Belmont Glass Works, Bellaire Window Glass Works, Enterprise Window Glass, and Bridgeport Glass.[18] Partially caused by the gas boom in Northwest Ohio, Bellaire had only three glass furnaces in 1891 after a peak of 17 in 1884.[19]

Northwest Ohio gas boom[edit]

In early 1886, a major discovery of natural gas occurred in Northwest Ohio near the small village of Findlay.[20] Although small natural gas wells had been drilled in the area earlier, the well drilled on property owned by Louis Karg was much more productive than those drilled before. Soon, many more wells were drilled, and the area experienced an economic boom as gas workers, businesses, and factories were drawn to the area.[20] In 1888, Findlay community leaders, assuming the supply of natural gas was unlimited, started a campaign to lure more manufacturing plants to the area. Incentives to relocate to Findlay included free natural gas, free land, and cash.[21] These incentives were especially attractive to glass manufacturers, since the glass manufacturing process is energy-intensive.[22]

The gas boom in Northwest Ohio enabled the state to improve its national ranking as a manufacturer of glass (based on value of product) from 4th in 1880 to 2nd in 1890.[23] Over 70 glass companies operated in northwest Ohio between 1880 and the early 20th century.[24] However, Northwest Ohio’s gas boom lasted less than five years. By 1890, the region was experiencing difficulty with its gas supply, and many manufacturers were already shutting down, using alternative fuels, or considering relocating.[24]

Bellaire[edit]

The Bellaire Goblet Company (sometimes mislabeled as Bellaire Goblet Works) received its charter from the state of Ohio on July 31, 1876.[25] It was organized in the fall by E. G. Morgan, Charles Henry Over, Henry Carr, John Robinson, Melvin L. Blackburn, and William A. Gorby. Morgan was president, Gorby was secretary and treasurer, and Over was manager.[26] Most of the founders were experienced glass men from the Belmont Glass Company with exception of Morgan, who provided capital.[27] Robinson and Over had also worked at the J. H. Hobbs, Brockunier and Company before being involved with the Belmont Glass startup.[28] The company's original glass product was exclusively goblets (glass stemware).[27] Production was conducted using a workforce of about 100 employees working a 10–pot furnace.[29] The company would eventually expand its products to include tableware and pressed stemware.[28]

During the 1870s, deflation was an economic issue for manufacturers. One source estimates that consumer prices decreased for seven years in that decade, while they remained unchanged for the other three.[30] To combat falling prices, manufacturers of similar products formed trade associations, typically known as holding companies or trusts.[31] (The Sherman Antitrust Act was not passed until 1890.[31]) During February 1877, a cartel named Pittsburgh and Wheeling Goblet Company was formed with the objective of limiting the sale of goblets below prices determined by the "partnership".[31] Eighteen manufacturers of goblets were part of the trust, and this included a non-union manufacturer: Bellaire Goblet Company.[Note 2] Competitive pressures prevailed, and the group disbanded on September 11, 1877.[31]

During March 1879, Bellaire Goblet leased (and eventually purchased) an additional glass plant that had an 8–pot furnace. That plant was expanded with the addition of a 14–pot gas furnace.[27] In September, the company's two factories had a capacity of 7,500 dozen goblets per week—and two months–worth of unfilled orders. They exported to South America, Germany, and Australia. Domestically, half of their product was sold in the eastern United States, especially Boston and New York. St. Louis, Chicago, Cincinnati, and San Francisco were major destinations for goblets in the west.[33] The company's employee count was about 150.[33]

In 1880, Bellaire Goblet Company had three furnaces with a total capacity of 29 pots.[34] This meant the company had 10 percent of Ohio's glassmaking capacity. It was also the largest of Bellaire's six glass manufacturers, and third largest of the 19 in the state.[35] By 1885, the employee count grew to 175 men and boys.[36] A report for 1887 listed Bellaire Goblet as having 285 employees and as one of eleven glass companies in Bellaire.[37] During March 1888, a newspaper noted that there was a "strong probability" that the company would move to Findlay, Ohio.[38]

Findlay[edit]

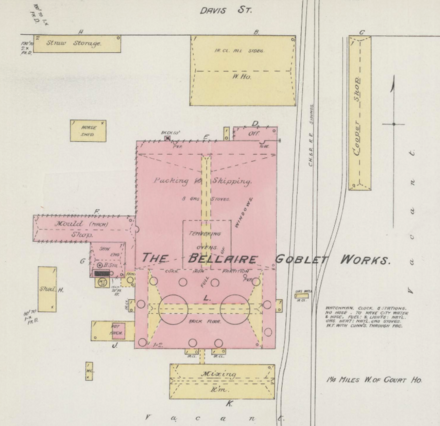

The management of Bellaire Goblet Company decided in March 1888 to move to Findlay, Ohio. A major reason for the move was the incentives: free natural gas for five years (important for the furnaces), free land, and $15,000 cash (equivalent to $508,667 in 2023).[39][Note 3] Construction of the glass works began in late April.[28] The new plant had two 15-pot furnaces, and equipment from the Bellaire works was shipped by rail to Findlay.[28] The plant's location in Findlay was on Bolton Avenue (between Davis and College streets) near a switching track from the Cincinnati, Hamilton and Dayton Railway.[41]

When Bellaire Goblet Company moved to Findlay, it leased its two Bellaire glass works to another glass company.[27] Charles Henry Over and company president E. G. Morgan decided to not move to Findlay. Melvin L. Blackburn became president while William Gorby continued as secretary and treasurer. John Robinson became plant manager, replacing Over.[28] Some of the Bellaire plant's 300 workers chose to remain in Bellaire and work for the company leasing the Bellaire glass works.[42]

Production in the new Findlay glass works began on August 13. The only problems were not factory–related: workers were difficult to find, and housing for the workers was scarce.[43] An inspector's report for 1888 listed the company as employing 250 males, 12 females, and 50 boys.[44] Production at the new plant went well and continued into the next year with no major problems. Then in the early morning of May 9, 1889, the plant was destroyed by fire in what was called the "most destructive fire in the history of Findlay".[45]

Rebuild and gas[edit]

The fire destroyed everything except the building's brick walls and furnaces. The total loss was estimated at over $100,000 (equivalent to $3,391,111 in 2023), and insurance covered about $65,000 (equivalent to $2,204,222 in 2023).[45] Although some newspapers said the glass works would be rebuilt at once, management was concerned about the availability of natural gas.[46] Even though the company had signed a contract for five years of free gas, the contract was nullified by Findlay's gas producer. Bellaire Goblet was offered a new contract, contingent on the company rebuilding the glass works as soon as possible, for gas at $400 (equivalent to $13,564 in 2023) per year for five years, which would be available if the city had a sufficient supply.[47] The company signed the contract on June 9, 1889, and the rebuild of the glass works began. The company's glassmakers were used as a construction workforce, and the plant resumed full production on August 18, 1889.[47] The Bellaire Goblet Company had a capacity of 30 pots, making it second in capacity among Findlay's twelve glass companies.[48]

In December 1890, gas rates were raised from $400 per year to $3,600 (equivalent to $122,080 in 2023), and the company was notified that if it did not pay at the new rate its gas would be shut off. The company claimed it already had an agreement to pay $400 per year, but the city said the contract was illegal.[49] On top of this potential huge increase in fuel costs, the domestic economy had been in recession since July 1890.[50] The company sued over the gas price increase—and lost.[51][Note 4] The unfavorable decision was made in late June 1891, but management was focused on something else. On July 1, 1891, the Bellaire Goblet Company ceased to exist as it became Factory M of the United States Glass Company.[53][Note 5]

Factory M[edit]

The objective of the U.S. Glass Company trust was to lower production costs.[55] Two ways to lower costs were to get concessions from the unions and to use more mechanization.[56] U.S. Glass preferred to produce glass using the most modern equipment with relatively unskilled workers.[57] It began construction of large glass works at Gas City, Indiana, and Glassport, Pennsylvania, which would be highly automated.[58] As fuel is another important cost in glassmaking, Gas City was participating in East Central Indiana's Gas Boom, and Glassport had a coal mine.[59]

Factory M began operations during August 1891, and it produced many of the original products made when it was Bellaire Goblet Company.[60] U.S. Glass management signed an agreement to pay $2,700 (equivalent to $91,560 in 2023) per year for the plant's natural gas fuel.[61] Factory M produced glass through December 8, 1892, before going on a holiday stop effective December 10.[62] Findlay's gas supply was very low, and all glass factories in town had switched to other fuel sources with the exception of two factories owned by U.S. Glass—Factory J and Factory M.[61] Factory J was in the process of switching to oil, but was still using gas.[54] Findlay gas trustees warned Factory M that it should immediately convert to oil for its fuel source., and then raised its gas price to $5,040 (equivalent to $170,912 in 2023) per year.[61] On January 12, 1893, after gas was cut off, U.S. Glass announced that it was shutting down Factory J and Factory M permanently.[63] Equipment from Factory M was stored at the empty Factory J, and eventually equipment from both factories was sent to the Gas City plant (Factory U). The Factory M property was sold to a non–glass manufacturer in May 1894, and the Factory J land was sold in 1910.[64]

Aftermath[edit]

Charles Henry Over, who did not move to Findlay, started the C. H. Over Glass Company in 1889. The plant was located in Muncie, Indiana, and employed 175 people.[65] William A. Gorby was a trustee for United States Glass Company. After Bellaire Goblet became Factory M, Gorby became a purchasing agent for U.S. Glass in Pittsburgh.[51] John Robinson resigned as plant manager and started Robinson Glass Company in Zanesville, Ohio. M. L. Blackburn joined Robinson Glass in 1892.[66]

During the Economic depression of 1893 (Panic of 1893), United States Glass Company negotiated with the union to change restrictive work rules and equalize wages in unionized and nonunion glass works. The union refused to make concessions, and a "lockout–strike" lasted from October 12, 1893, until January 1897.[67] During much of that time glass was still made at the two large plants in Gas City and Glassport, and the company did not suffer from significant financial difficulties.[58] In 1896, the company was operating six plants: three in Pittsburg (Factories B, F, and K), and three more in Tiffin, Gas City, and Glassport.[68][Note 6] Some of the other plants were closed permanently during the strike, including four that were destroyed by fire.[71] The company experienced more strikes in 1913, including at Gas City and Glassport, and reached a settlement where all of its plants became unionized.[72] More plants were closed during the Great Depression in the 1930s. The company filed for bankruptcy in 1962.[73]

Notes[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Each ceramic pot was located inside a furnace. The pot contained molten glass created by melting a batch of ingredients that typically included sand, soda, lime, and other ingredients.[5]

- ^ The eighteen companies in the Pittsburgh and Wheeling Goblet Company "partnership" were: Adams & Co.; Bakewell, Pears & Co.; Bellaire Goblet Co.; Belmont Glass Co.; Bryce, Walker & Co.; Campbell, Jones & Co.; Central Glass Co.; Crystal Glass Co.; Doyle & Co.; George Duncan & Sons; Excelsior Glass Co.; J. H. Hobbs, Brockunier & Co.; King, Son & Co.; La Belle Glass Co.; McKee & Bro.; O'Hara Glass Co. Limited; Richards & Hartley Flint Glass Co.; and Ripley & Company.[31] In 1891, some of these companies joined a tableware trust named United States Glass Company.[32]

- ^ Paquette's sources for information on the incentives are the March 27, 1888 edition of the Findlay Dispatch–Courier; the April 19 and 26, 1888 editions of the Pottery and Glass Reporter, and the June 9, 1889 edition of the Findlay Republican.[40] A December 17, 1903, article in the Crockery and Glass Journal says the cash incentive was $20,000 (equivalent to $678,222 in 2023).[19]

- ^ Paquette got the information on the gas dispute from local newspapers and an in-depth account from the July 21, 1891 edition of Pottery and Glass Reporter.[52]

- ^ A second glass manufacturer in Findlay, Columbia Glass Company, became Factory J of U.S. Glass Company.[54]

- ^ Factory B was the former Bryce Brothers, Factory F was the former Ripley & Company, and Factory K was the former King Glass Company.[69] The Tiffin plant, Factory R, was the former A. J. Beatty & Sons.[70]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b "How Glass is Made – What is glass made of? The wonders of glass all come down to melting sand". Corning. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 45

- ^ "Corning Museum of Glass – Annealing Glass". Corning Museum of Glass. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ "Corning Museum of Glass – Lehr". Corning Museum of Glass. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ Skrabec 2007a, pp. 25–26

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 12

- ^ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 13; Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 36

- ^ O.W. Gray (1873). Rail road map of Ohio 1873 (retrieved from the Library of Congress) (Map). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: O.W. Gray. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023. Retrieved October 4, 2023.; McKelvey 1903, p. 79

- ^ Bruno & Ehritz 2009, p. 7

- ^ Howe 1888, p. 321

- ^ O.W. Gray (1873). Rail road map of Ohio 1873 (retrieved from the Library of Congress) (Map). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: O.W. Gray. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ McKelvey 1903, p. 171

- ^ McKelvey 1903, p. 68

- ^ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, pp. 78–79

- ^ Cranmer et al. 1890, pp. 484, 756

- ^ McKelvey 1903, p. 170

- ^ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, pp. 11, 15

- ^ State of Ohio & Dorn (Chief State Inspector) 1889, pp. 37–38

- ^ a b "The Glass Factories - A review of the trade in the Ohio Valley for the past thirty years". Crockery & Glass Journal. 58 (25). New York, New York: Whittemore and Jaques, Inc.: 123–125 December 17, 1903.

- ^ a b Paquette 2002, pp. 24–25; Skrabec 2007, pp. 7, 25

- ^ Paquette 2002, p. 26

- ^ "Glass manufacturing is an energy-intensive industry mainly fueled by natural gas". U.S. Energy Information Administration. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ United States Census Office 1895, p. 315

- ^ a b Paquette 2002, p. 28

- ^ Bell, Jr. 1877, p. 190

- ^ Caldwell & Newton 1880, pp. 261–262; Paquette 2002, p. 26

- ^ a b c d Cranmer et al. 1890, p. 485

- ^ a b c d e Paquette 2002, p. 57

- ^ Caldwell & Newton 1880, p. 261; Cranmer et al. 1890, p. 485

- ^ "Consumer Price Index, 1800– (Historic data including estimates before the modern U.S. consumer price index)". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Archived from the original on June 19, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Measell, James S. (April 1988). "Notes and Documents: The Pittsburgh and Wheeling Goblet Company". The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine. 71 (2). Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania (Penn State Libraries Open Publishing): 191–195. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "The Tableware Trust (page 1 2nd col. from right)". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). February 21, 1891. Archived from the original on August 7, 2023. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- ^ a b "Bellaire Goblet Works". Cincinnati Commercial. September 10, 1879. p. 12.

...the only establishment in the world devoted exclusively to the manufacturer of all kinds of stem goblets....

- ^ Ohio Bureau of Labor Statistics & Walls 1881, p. 181

- ^ Ohio Bureau of Labor Statistics & Walls 1881, pp. 181–182

- ^ "Untitled (page 3 third column from left near top)". Belmont Chronicle (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). October 15, 1885. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ Howe 1888, p. 320

- ^ "Untitled (page 3 4th column near bottom)". Belmont Chronicle (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). March 29, 1888. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ Paquette 2002, pp. 56, 59

- ^ Paquette 2002, pp. 56, 59, 488

- ^ Lambert 2019, p. 47; Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. (1890). Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Findlay, Hancock County, Ohio – (see area 16 in upper left of image 1 ) (Map). New York, New York: Sanborn Perris Map Co. Archived from the original on July 9, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ Paquette 2002, pp. 56–57

- ^ Paquette 2002, p. 58

- ^ State of Ohio & Dorn (Chief State Inspector) 1889, p. 55

- ^ a b Paquette 2002, p. 58; "Bellaire Goblet Works – The Largest in the World, Burned to the Ground (page 1 column 6)". Daily Kennebec Journal (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). May 10, 1889. Archived from the original on 2023-10-19. Retrieved 2023-10-05.; "Wiped Out by Flames (page 8 column 3)". Pittsburgh Dispatch (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). May 10, 1889. Archived from the original on October 19, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ "Bellaire Goblet Works – The Largest in the World, Burned to the Ground (page 1 column 6)". Daily Kennebec Journal (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). May 10, 1889. Archived from the original on October 19, 2023. Retrieved October 5, 2023.; "Goblet Works Burned (page 1 right column halfway down)". Savannah Morning News (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). May 10, 1889. Archived from the original on October 19, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.; Paquette 2002, p. 59

- ^ a b Paquette 2002, p. 59

- ^ Geological Survey of Ohio, Robinson & Orton 1890, p. 119

- ^ Paquette 2002, pp. 59–60

- ^ "US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions". National Bureau of Economic Research. Archived from the original on December 1, 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Paquette 2002, p. 60

- ^ Paquette 2002, pp. 59–60, 488

- ^ Paquette 2002, p. 60; "Unlucky thirteen (page 19 column 6 top)". Pittsburg Dispatch (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). July 11, 1891. Archived from the original on October 19, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.; "Will Be Known by Letters (page 2 column 5 near bottom)". Pittsburg Dispatch (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). September 4, 1891. Archived from the original on October 19, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Paquette 2002, p. 99

- ^ "The New Glass Trust (page 5 column 4)". Wheeling Daily Intelligencer (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). June 30, 1891. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 23

- ^ Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 8

- ^ a b Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 24

- ^ Glass, James A. (December 2000). "The Gas Boom in East Central Indiana". Indiana Magazine of History. 96 (4). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press: 313–335. JSTOR 27792274. Retrieved October 11, 2023.; Pennsylvania & Roderick 1901, p. 643

- ^ Lechner & Lechner 1998, p. 32

- ^ a b c Paquette 2002, p. 101

- ^ Lechner & Lechner 1998, p. 32; Paquette 2002, p. 101

- ^ Lechner & Lechner 1998, p. 32; Paquette 2002, pp. 99, 101

- ^ Paquette 2002, pp. 99–101

- ^ Paquette 2002, p. 117; Glass & Kohrman 2005, p. 26

- ^ Iwen, Marg (Winter 2004). "The Robinsons of Zanesville 1893–1900" (PDF). Bottles and Extras (Antique Bottle and Glass Collector). 15. The Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors: 2–8. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2023.; Paquette 2002, p. 60

- ^ "US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions". National Bureau of Economic Research. Archived from the original on December 1, 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2023.; Steele, Eilsworth (September 1954). "The Flint Glass Workers' Union in the Indiana Gas Belt and the Ohio Valley in the 1890's". Indiana Magazine of History. 50 (3). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press: 229–250. JSTOR 27788200. Retrieved October 13, 2023.; Bredehoft & Bredehoft 1997, p. 24

- ^ "United States Glass Company". Glass and Pottery World. IV (11). Chicago, Illinois: American Glass and Pottery World Company: 9. November 1896.

- ^ "Will Be Known by Letters (page 2 column 5 near bottom)". Pittsburg Dispatch (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). September 4, 1891. Archived from the original on October 19, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ Paquette 2002, pp. 431–432

- ^ Shotwell 2002, p. 579; Paquette 2002, p. 218

- ^ "The U. S. Strike". The American Flint. XVI (7). Toledo, Ohio: American Flint Glass Workers' Union of North America: 9. May 1925. Archived from the original on October 19, 2023. Retrieved October 13, 2023.

- ^ Shotwell 2002, p. 579

References[edit]

- Bell, Jr., William (1877). Annual Report of the Secretary of State to the Governor of the State of Ohio...for the year 1876. Columbus, Ohio: Nevins and Myers, State Printers. OCLC 2421686. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- Bredehoft, Neila M.; Bredehoft, Thomas H. (1997). Hobbs, Brockunier and Co., Glass: Identification and Value Guide. Paducah, KY: Collector Books. ISBN 978-0-89145-780-0. OCLC 37340501.

- Bruno, Holly; Ehritz, Andrew (2009). Bellaire. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-6006-9. OCLC 320804618.

- Caldwell, John Alexander; Newton, J. H. (1880). History of Belmont and Jefferson Counties, Ohio: and Incidentally Historical Collections Pertaining to Border Warfare and the Early Settlement of the Adjacent Portion of the Ohio Valley. Wheeling, West Virginia: Historical Publishing Company. OCLC 1029864213. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- Cranmer, Gibson L.; Jepson, Samuel L.; Trainer, John H.S. and William Morrison; Taneyhill, R. H. (1890). History of the Upper Ohio Valley: with Family History and Biographical Sketches. A statement of its resources, industrial growth and commercial advantages ... Vol. I & II. Madison, WI: Brant & Fuller. OCLC 49762897.

- Geological Survey of Ohio; Robinson, S. W.; Orton, Edward (1890). First Annual Report of the Geological Survey of Ohio. Columbus, Ohio: Westbote Co., State Printers. OCLC 1026686144. Archived from the original on August 3, 2023. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- Glass, James A.; Kohrman, David (2005). The Gas Boom of East Central Indiana. Charleston, SC: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-7385-3963-8. OCLC 61885891.

- Howe, Henry (1888). Historical Collections of Ohio in Two Volumes. An Encyclopedia of the State - Vol. I. Cincinnati, Ohio: State of Ohio. OCLC 1068774. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved October 3, 2023.

- Lambert, Teresa Straley (2019). Lost Hancock County, Ohio. Charleston, South Carolina: History Press. ISBN 978-1-46714-135-2. OCLC 1102472234.

- Lechner, Mildred; Lechner, Ralph (1998). The World of Salt Shakers: Antique & Art Glass Value Guide Volume III. Paducah, Kentucky: Collector Books. ISBN 978-1-57432-065-7. OCLC 39502285.

- McKelvey, Alexander T. (1903). Centennial History of Belmont County, Ohio and Representative Citizens. Chicago: Biographical Publishing Company. OCLC 1029853230. Archived from the original on 2023-10-10. Retrieved 2023-09-29.

- Ohio Bureau of Labor Statistics; Walls, H. J. (1881). Fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, made to the General Assembly of the State of Ohio, for the year 1880. Columbus, Ohio: G. J. Brand & Co., State Printers. OCLC 8421878. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- Paquette, Jack K. (2002). Blowpipes, Northwest Ohio Glassmaking in the Gas Boom of the 1880s. Xlibris Corp. ISBN 1-4010-4790-4. OCLC 50932436.

- Pennsylvania; Roderick, James E. (1901). Report of the Bureau of Mines of the Department of Internal Affairs of Pennsylvania – 1900. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Wm. Stanley Ray, State Printer of Pennsylvania. OCLC 48787455. Archived from the original on October 19, 2023. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- Shotwell, David J. (2002). Glass A to Z. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. ISBN 978-0-87349-385-7. OCLC 440702171.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2007). Glass in Northwest Ohio. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-73855-111-1. OCLC 124093123.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2007a). Michael Owens and the Glass Industry. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-1-45560-883-6. OCLC 1356375205.

- State of Ohio; Dorn (Chief State Inspector), Henry (1889). Fifth Annual Report of the Chief State Inspector of Workshops and Factories, to the General Assembly of the State of Ohio, for the year 1888. Columbus, Ohio: Office Chief State Inspector of Workshops and Factories (The Westbote Company, State Printers). OCLC 13049818. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- United States Census Office (1895). Report on manufacturing industries in the United States at the eleventh census: 1890. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 10470409.

- United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce (1917). The Glass Industry. Report on the Cost of Production of Glass in the United States. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 5705310.

- Weeks, Joseph D.; United States Census Office (1884). Report on the Manufacture of Glass. Washington, District of Columbia: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 2123984. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

External links[edit]

- Bellaire Goblet Company various patterns – Early American Pattern Glass Society

- Bellaire Goblet Company various patterns – The Museum of American Glass in West Virginia

- Findlay's tableware glass factories – Hancock Historical Museum