Canberra

| Canberra Kanbarra (Ngunawal) Australian Capital Territory | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

City map plan of Canberra | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Coordinates | 35°17′35″S 149°07′37″E / 35.29306°S 149.12694°E | ||||||||

| Population | 466,566 (June 2023)[1] (8th) | ||||||||

| • Density | 503.932/km2 (1,305.18/sq mi) | ||||||||

| Established | 12 March 1913 | ||||||||

| Elevation | 578 m (1,896 ft)[2] | ||||||||

| Area | 814.2 km2 (314.4 sq mi)[3] | ||||||||

| Time zone | AEST (UTC+10:00) | ||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | AEDT (UTC+11:00) | ||||||||

| Location | |||||||||

| Territory electorate(s) | |||||||||

| Federal division(s) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Canberra (/ˈkænbərə/ ⓘ KAN-bər-ə) is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest Australian city overall. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory[10] at the northern tip of the Australian Alps, the country's highest mountain range. As of June 2023,[update] Canberra's estimated population was 466,566.[1]

The area chosen for the capital had been inhabited by Aboriginal Australians for up to 21,000 years,[11] by groups including the Ngunnawal, Ngunawal and Ngambri.[12] European settlement commenced in the first half of the 19th century, as evidenced by surviving landmarks such as St John's Anglican Church and Blundells Cottage. On 1 January 1901, federation of the colonies of Australia was achieved. Following a long dispute over whether Sydney or Melbourne should be the national capital,[13] a compromise was reached: the new capital would be built in New South Wales, so long as it was at least 100 mi (160 km) from Sydney. The capital city was founded and formally named as Canberra in 1913. A plan by the American architects Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin was selected after an international design contest, and construction commenced in 1913.[14][15] Unusual among Australian cities, it is an entirely planned city. The Griffins' plan featured geometric motifs and was centred on axes aligned with significant topographical landmarks such as Black Mountain, Mount Ainslie, Capital Hill and City Hill. Canberra's mountainous location makes it the only mainland Australian city where snow-capped mountains can be seen in winter, although snow in the city itself is uncommon.

As the seat of the Government of Australia, Canberra is home to many important institutions of the federal government, national monuments and museums. This includes Parliament House, Government House, the High Court building and the headquarters of numerous government agencies. It is the location of many social and cultural institutions of national significance such as the Australian War Memorial, the Australian National University, the Royal Australian Mint, the Australian Institute of Sport, the National Gallery, the National Museum and the National Library. The city is home to many important institutions of the Australian Defence Force including the Royal Military College Duntroon and the Australian Defence Force Academy. It hosts all foreign embassies in Australia as well as regional headquarters of many international organisations, not-for-profit groups, lobbying groups and professional associations.

Canberra has been ranked among the world's best cities to live in and visit.[16][17][18][19][20] Although the Commonwealth Government remains the largest single employer in Canberra, it is no longer the majority employer. Other major industries have developed in the city, including in health care, professional services, education and training, retail, accommodation and food, and construction.[21] Compared to the national averages, the unemployment rate is lower and the average income higher; tertiary education levels are higher, while the population is younger. At the 2016 Census, 32% of Canberra's inhabitants were reported as having been born overseas.[22]

Canberra's design is influenced by the garden city movement and incorporates significant areas of natural vegetation. Its design can be viewed from its highest point at the Telstra Tower and the summit of Mount Ainslie. Other notable features include the National Arboretum, born out of the 2003 Canberra bushfires, and Lake Burley Griffin, named for Walter Burley Griffin. Highlights in the annual calendar of cultural events include Floriade, the largest flower festival in the Southern Hemisphere,[23][24] the Enlighten Festival, Skyfire, the National Multicultural Festival and Summernats. Canberra's main sporting venues are Canberra Stadium and Manuka Oval. The city is served with domestic and international flights at Canberra Airport, while interstate train and coach services depart from Canberra railway station and the Jolimont Centre respectively. City Interchange is the main hub of Canberra's bus and light rail transport network.

Name

The word "Canberra" is derived from the Ngunnawal language of a local Ngunnawal or Ngambri clan who resided in the area and were referred to by the early British colonists as either the Canberry, Kanberri or Nganbra tribe.[25][26] Joshua John Moore, the first European land-owner in the region, named his grant "Canberry" in 1823 after these people. "Canberry Creek" and "Canberry" first appeared on regional maps from 1830, while the derivative name "Canberra" started to appear from around 1857.[27][28][29]

Numerous local commentators, including the Ngunnawal elder Don Bell, have speculated upon possible meanings of "Canberra" over the years. These include "meeting place", "woman's breasts" and "the hollow between a woman's breasts".[30][31]

Alternative proposals for the name of the city during its planning included Austral, Australville, Aurora, Captain Cook, Caucus City, Cookaburra, Dampier, Eden, Eucalypta, Flinders, Gonebroke, Home, Hopetoun, Kangaremu, Myola, Meladneyperbane, New Era, Olympus, Paradise, Shakespeare, Sydmelperadbrisho, Swindleville, The National City, Union City, Unison, Wattleton, Wheatwoolgold, Yass-Canberra.[32][33][34]

History

First Nations peoples

The first peoples of the Canberra area include the Ngunnawal, Ngunawal and Ngambri peoples.[12] Other groups claiming a connection to the land include the Ngarigo (who also lived directly to the south) and the Ngambri-Guumaal.[25] Neighbouring groups include the Wandandian to the east, the Walgulu also to the south, Gandangara people to the north and Wiradjuri to the north-west.

The first British settlers into the Canberra area described two clans of Ngunnawal people resident to the vicinity. The Canberry or Nganbra clan lived mostly around Sullivan's Creek and had ceremonial grounds at the base of Galambary (Black Mountain), while the Pialligo clan had land around what is now Canberra Airport.[35][36] The people living here carefully managed and cultivated the land with fire and farmed yams and hunted for food.[37]

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the region includes inhabited rock shelters, rock paintings and engravings, burial places, camps and quarry sites as well as stone tools and arrangements.[38] Artefacts suggests early human activity occurred at some point in the area 21,000 years previously.[11]

Still today, Ngunnawal men into the present conduct ceremony on the banks of the river, Murrumbidgee River. They travel upstream as they receive their Totems and corresponding responsibilities for land management. 'Murrum' means 'Pathway' and Bidgee means 'Boss'.[37]

The submerged limestone caves beneath Lake Burley Griffin contained Aboriginal rock art, some of the only sites in the region.[37]

Galambary (Black Mountain) is an important Aboriginal meeting and business site, predominantly for men's business. According to the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, Mt Ainslie is primarily for place of women's business. Black Mountain and Mount Ainslie are referred to as women's breasts. Galambary was also used by Ngunnawal people as an initiation site, with the mountain itself said to represent the growth of a boy into a man.[37]

British exploration and colonisation

In October 1820, Charles Throsby led the first British expedition to the area.[40][41][42][43] Four other expeditions occurred between 1820 and 1823 with the first accurate map being produced by explorer Mark John Currie in June 1823. By this stage the area had become known as the Limestone Plains.[40][44]

British settlement of the area probably dates from late 1823, when a sheep station was formed on what is now the Acton Peninsula by James Cowan, the head stockman employed by Joshua John Moore.[45] Moore had received a land grant in the region in 1823 and formally applied to purchase the site on 16 December 1826. He named the property "Canberry". On 30 April 1827, Moore was told by letter that he could retain possession of 1,000 acres (405 ha) at Canberry.[46]

Other colonists soon followed Moore's example to take up land in the region. Around 1825 James Ainslie, working on behalf of the wealthy merchant Robert Campbell, arrived to establish a sheep station. He was guided to the region by a local Aboriginal girl who showed him the fine lands of her Pialligo clan.[35] The area then became the property of Campbell and it was initially named Pialligo before Campbell changed it to the Scottish title of Duntroon.[27][47][48] Campbell's family later built the imposing stone house that is now the officers' mess of the Royal Military College, Duntroon.[49] The Campbells sponsored settlement by other farmer families to work their land, such as the Southwells of "Weetangera".[50]

Other notable early colonists included Henry Donnison, who established the Yarralumla estate—now the site of the official residence of the Governor-General of Australia—in 1827, and John Palmer who employed Duncan Macfarlane to form the Jerrabomberra property in 1828. A year later, John MacPherson established the Springbank estate, becoming the first British owner-occupier in the region.[27][51][52]

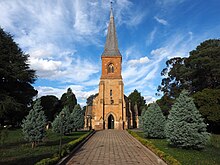

The Anglican church of St John the Baptist, in the suburb of Reid,[53] was consecrated in 1845 and is now the oldest surviving public building in the city.[54][55] St John's churchyard contains the earliest graves in the district.[56] It has been described as a "sanctuary in the city",[57][58] remaining a small English village-style church even as the capital grew around it. Canberra's first school, St John's School (now a museum), was situated next to the church and opened in the same year of 1845.[59] It was built to educate local settlers children,[60] including the Blundell children who lived in nearby Blundell's Cottage.[61]

As the European presence increased, the Indigenous population dwindled largely due to the destruction of their society, dislocation from their lands and from introduced diseases such as influenza, smallpox, alcoholism and measles.[62][63]

Creation of the nation's capital

The district's change from a rural area in New South Wales to the national capital started during debates over federation in the late 19th century.[64][65] Following a long dispute over whether Sydney or Melbourne should be the national capital,[13] a compromise was reached: the new capital would be built in New South Wales, so long as it was at least 100 mi (160 km) from Sydney,[64] with Melbourne to be the temporary seat of government while the new capital was built.[66] A survey was conducted across several sites in New South Wales with Bombala, southern Monaro, Orange, Yass, Albury, Tamworth, Armidale, Tumut and Dalgety all discussed.[67] Dalgety was chosen by the federal parliament and it passed the Seat of Government Act 1904 confirming Dalgety as the site of the nation's capital. However, the New South Wales government refused to cede the required territory as they did not accept the site.[67] In 1906, the New South Wales Government finally agreed to cede sufficient land provided that it was in the Yass-Canberra region as this site was closer to Sydney.[64] Newspaper proprietor John Gale circulated a pamphlet titled 'Dalgety or Canberra: Which?' advocating Canberra to every member of the Commonwealth's seven state and federal parliaments. By many accounts, it was decisive in the selection of Canberra as the site in 1908 as was a result of survey work done by the government surveyor Charles Scrivener.[68] The NSW government ceded the district to the federal government in 1911 and the Federal Capital Territory was established.[64]

An international design competition was launched by the Department of Home Affairs on 30 April 1911, closing on 31 January 1912. The competition was boycotted by the Royal Institute of British Architects, the Institution of Civil Engineers and their affiliated bodies throughout the British Empire because the Minister for Home Affairs King O'Malley insisted that the final decision was for him to make rather than an expert in city planning.[69] A total of 137 valid entries were received. O'Malley appointed a three-member board to advise him but they could not reach unanimity. On 24 May 1911,[70] O'Malley came down on the side of the majority of the board with the design by Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin of Chicago, Illinois, United States, being declared the winner.[71][72] Second was Eliel Saarinen of Finland and third was Alfred Agache of Brazil but resident in Paris, France.[69] O'Malley then appointed a six-member board to advise him on the implementation of the winning design. On 25 November 1912, the board advised that it could not support the Griffins' plan in its entirety and suggested an alternative plan of its own devising. This plan ostensibly incorporated the best features of the three place-getting designs as well as of a fourth design by H. Caswell, R.C.G. Coulter and W. Scott-Griffiths of Sydney, the rights to which it had purchased. It was this composite plan that was endorsed by Parliament and given formal approval by O'Malley on 10 January 1913.[69] However, it was the Griffin plan which was ultimately proceeded with. In 1913, Walter Burley Griffin was appointed Federal Capital Director of Design and Construction and construction began.[73] On 23 February, King O'Malley drove the first peg in the construction of the future capital city.

In 1912, the government invited suggestions from the public as to the name of the future city. Almost 750 names were suggested. At midday on 12 March 1913,[74][75] Lady Denman, the wife of Governor-General Lord Denman, announced that the city would be named "Canberra" at a ceremony at Kurrajong Hill,[76][77][78] which has since become Capital Hill and the site of the present Parliament House.[79] Canberra Day is a public holiday observed in the ACT on the second Monday in March to celebrate the founding of Canberra.[63] After the ceremony, bureaucratic disputes hindered Griffin's work;[80] a Royal Commission in 1916 ruled his authority had been usurped by certain officials and his original plan was reinstated.[81] Griffin's relationship with the Australian authorities was strained and a lack of funding meant that by the time he was fired in 1920, little work had been done.[82][83] By this time, Griffin had revised his plan, overseen the earthworks of major avenues and established the Glenloch Cork Plantation.[84][85]

Development throughout 20th century

The Commonwealth government purchased the pastoral property of Yarralumla in 1913 to provide an official residence for the Governor-General of Australia in the new capital.[86] Renovations began in 1925 to enlarge and modernise the property.[87] In 1927, the property was official dubbed Government House.[86] On 9 May that year, the Commonwealth parliament moved to Canberra with the opening of the Provisional Parliament House.[88][89] The Prime Minister Stanley Bruce had officially taken up residence in The Lodge a few days earlier.[90][91] Planned development of the city slowed significantly during the depression of the 1930s and during World War II.[92] Some projects planned for that time, including Roman Catholic and Anglican cathedrals, were never completed.[93] (Nevertheless, in 1973 the Roman Catholic parish church of St. Christopher was remodelled into St. Christopher's Cathedral, Manuka, serving the Archdiocese of Canberra and Goulburn. It is the only cathedral in Canberra.[94])

From 1920 to 1957, three bodies — successively the Federal Capital Advisory Committee,[95] the Federal Capital Commission,[96] and the National Capital Planning and Development Committee — continued to plan the further expansion of Canberra in the absence of Griffin. However, they were only advisory and development decisions were made without consulting them, which increased inefficiency.[84][97]

The largest event in Canberra up to World War II was the 24th Meeting of ANZAAS in January 1939. The Canberra Times described it as "a signal event ... in the history of this, the world's youngest capital city". The city's accommodation was not nearly sufficient to house the 1,250 delegates and a tent city had to be set up on the banks of the Molonglo River. One of the prominent speakers was H. G. Wells, who was a guest of the Governor-General Lord Gowrie for a week. This event coincided with a heatwave across south-eastern Australia during which the temperature in Canberra reached 108.5 degrees Fahrenheit (42.5 Celsius) on 11 January. On Friday, 13 January, the Black Friday bushfires caused 71 deaths in Victoria and Wells accompanied the Governor-General on his tour of areas threatened by fires.[98]

Immediately after the end of the war, Canberra was criticised for resembling a village and its disorganised collection of buildings was deemed ugly.[99][100][101] Canberra was often derisively described as "several suburbs in search of a city".[102] Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies regarded the state of the national capital as an embarrassment.[103] Over time his attitude changed from one of contempt to that of championing its development. He fired two ministers charged with the development of the city for poor performance. Menzies remained in office for over a decade and in that time the development of the capital sped up rapidly.[104][105] The population grew by more than 50 per cent in every five-year period from 1955 to 1975.[105] Several Government departments, together with public servants, were moved to Canberra from Melbourne following the war.[106] Government housing projects were undertaken to accommodate the city's growing population.[107]

The National Capital Development Commission (NCDC) formed in 1957 with executive powers and ended four decades of disputes over the shape and design of Lake Burley Griffin — the centrepiece of Griffin's design — and construction was completed in 1964 after four years of work.[108] The completion of the lake finally laid the platform for the development of Griffin's Parliamentary Triangle.[109] Since the initial construction of the lake, various buildings of national importance have been constructed on its shores.[110]

The newly built Australian National University was expanded and sculptures as well as monuments were built.[110][111] A new National Library was constructed within the Parliamentary Triangle, followed by the High Court and the National Gallery.[53][112] Suburbs in Canberra Central (often referred to as North Canberra and South Canberra) were further developed in the 1950s and urban development in the districts of Woden Valley and Belconnen commenced in the mid and late 1960s respectively.[113][114] Many of the new suburbs were named after Australian politicians such as Barton, Deakin, Reid, Braddon, Curtin, Chifley and Parkes.[115]

On 9 May 1988, a larger and permanent Parliament House was opened on Capital Hill as part of Australia's bicentenary celebrations.[116][112] The Commonwealth Parliament moved there from the Provisional Parliament House, now known as Old Parliament House.[116]

Self-government

In December 1988, the Australian Capital Territory was granted full self-government by the Commonwealth Parliament, a step proposed as early as 1965.[117] Following the first election on 4 March 1989,[118] a 17-member Legislative Assembly sat at temporary offices at 1 Constitution Avenue, Civic, on 11 May 1989.[119][120] Permanent premises were opened on London Circuit in 1994.[120] The Australian Labor Party formed the ACT's first government, led by the Chief Minister Rosemary Follett, who made history as Australia's first female head of government.[121][122]

Parts of Canberra were engulfed by bushfires on 18 January 2003 that killed four people, injured 435 and destroyed more than 500 homes as well as the major research telescopes of Australian National University's Mount Stromlo Observatory.[123]

Throughout 2013, several events celebrated the 100th anniversary of the naming of Canberra.[124] On 11 March 2014, the last day of the centennial year, the Canberra Centenary Column was unveiled in City Hill. Other works included The Skywhale, a hot air balloon designed by the sculptor Patricia Piccinini,[125] and StellrScope by visual media artist Eleanor Gates-Stuart.[126] On 7 February 2021, The Skywhale was joined by Skywhalepapa to create a Skywhale family, an event marked by Skywhale-themed pastries and beer produced by local companies as well as an art pop song entitled "We are the Skywhales".[127]

In 2014, Canberra was named the best city to live in the world by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,[16] and was named the third best city to visit in the world by Lonely Planet in 2017.[19][20]

Geography

Canberra covers an area of 814.2 km2 (314.4 sq mi)[3] and is located near the Brindabella Ranges (part of the Australian Alps), approximately 150 km (93 mi) inland from Australia's east coast. It has an elevation of approximately 580 m (1,900 ft) AHD;[128] the highest point is Mount Majura at 888 m (2,913 ft).[129][130] Other low mountains include Mount Taylor 855 m (2,805 ft),[131] Mount Ainslie 843 m (2,766 ft),[132] Mount Mugga Mugga 812 m (2,664 ft)[133] and Black Mountain 812 m (2,664 ft).[134][135]

The native forest in the Canberra region was almost wholly eucalypt species and provided a resource for fuel and domestic purposes. By the early 1960s, logging had depleted the eucalypt, and concern about water quality led to the forests being closed. Interest in forestry began in 1915 with trials of a number of species including Pinus radiata on the slopes of Mount Stromlo. Since then, plantations have been expanded, with the benefit of reducing erosion in the Cotter catchment, and the forests are also popular recreation areas.[136]

The urban environs of the city of Canberra straddle the Ginninderra plain, Molonglo plain, the Limestone plain, and the Tuggeranong plain (Isabella's Plain).[137] The Molonglo River which flows across the Molonglo plain has been dammed to form the national capital's iconic feature Lake Burley Griffin.[138] The Molonglo then flows into the Murrumbidgee north-west of Canberra, which in turn flows north-west toward the New South Wales town of Yass. The Queanbeyan River joins the Molonglo River at Oaks Estate just within the ACT.[137]

A number of creeks, including Jerrabomberra and Yarralumla Creeks, flow into the Molonglo and Murrumbidgee.[137] Two of these creeks, the Ginninderra and Tuggeranong, have similarly been dammed to form Lakes Ginninderra and Tuggeranong.[139][140][141] Until recently the Molonglo River had a history of sometimes calamitous floods; the area was a flood plain prior to the filling of Lake Burley Griffin.[142][143]

Climate

Under the Köppen-Geiger classification, Canberra has an oceanic climate (Cfb).[144] In January, the warmest month, the average high is approximately 29 °C (84 °F); in July, the coldest month, the average high drops to approximately 12 °C (54 °F).

Frost is common in the winter months. Snow is rare in the CBD (central business district) due to being on the leeward (eastern) side of the dividing range, but the surrounding areas get annual snowfall through winter and often the snow-capped Brindabella Range can be seen from the CBD. The last significant snowfall in the city centre was in 1968.[128] Canberra is often affected by foehn winds, especially in winter and spring, evident by its anomalously warm maxima relative to altitude.

The highest recorded maximum temperature was 44.0 °C (111.2 °F) on 4 January 2020.[145] Winter 2011 was Canberra's warmest winter on record, approximately 2 °C (4 °F) above the average temperature.[146]

The lowest recorded minimum temperature was −10.0 °C (14.0 °F) on the morning of 11 July 1971.[128] Light snow falls only once in every few years, and is usually not widespread and quickly dissipates.[128]

Canberra is protected from the west by the Brindabellas which create a strong rain shadow in Canberra's valleys.[128] Canberra gets 100.4 clear days annually.[147] Annual rainfall is the third lowest of the capital cities (after Adelaide and Hobart)[148] and is spread fairly evenly over the seasons, with late spring bringing the highest rainfall.[149] Thunderstorms occur mostly between October and April,[128] owing to the effect of summer and the mountains. The area is generally sheltered from a westerly wind, though strong northwesterlies can develop. A cool, vigorous afternoon easterly change, colloquially referred to as a 'sea-breeze' or the 'Braidwood Butcher',[150][151] is common during the summer months[152] and often exceeds 40 km/h in the city. Canberra is also less humid than the nearby coastal areas.[128]

Canberra was severely affected by smoke haze during the 2019/2020 bushfires. On 1 January 2020, Canberra had the worst air quality of any major city in the world, with an AQI of 7700 (USAQI 949).[153]

| Climate data for Canberra Airport Comparison (1991–2010 averages, extremes 1939–2023); 578 m AMSL; 35.30° S, 149.20° E | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 44.0 (111.2) |

42.7 (108.9) |

37.5 (99.5) |

32.6 (90.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.1 (68.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

24.0 (75.2) |

30.2 (86.4) |

32.7 (90.9) |

39.9 (103.8) |

41.6 (106.9) |

44.0 (111.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 28.8 (83.8) |

27.8 (82.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

16.6 (61.9) |

12.9 (55.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.4 (74.1) |

26.5 (79.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.4 (70.5) |

20.8 (69.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

6.2 (43.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.4 (38.1) |

1.6 (34.9) |

0.3 (32.5) |

1.2 (34.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.1 (53.8) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 1.6 (34.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

0.3 (32.5) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 61.3 (2.41) |

55.2 (2.17) |

37.6 (1.48) |

27.3 (1.07) |

31.5 (1.24) |

50.0 (1.97) |

44.3 (1.74) |

43.1 (1.70) |

55.8 (2.20) |

50.9 (2.00) |

68.4 (2.69) |

54.1 (2.13) |

579.5 (22.81) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 6.8 | 6.7 | 5.7 | 5.4 | 6.3 | 9.7 | 10.0 | 8.5 | 9.8 | 9.1 | 10.2 | 7.2 | 95.4 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 37 | 40 | 42 | 46 | 54 | 60 | 58 | 52 | 49 | 47 | 41 | 37 | 47 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 8.6 (47.5) |

9.8 (49.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

6.4 (43.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

2.3 (36.1) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

6.9 (44.4) |

5.7 (42.3) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 294.5 | 254.3 | 251.1 | 219.0 | 186.0 | 156.0 | 179.8 | 217.0 | 231.0 | 266.6 | 267.0 | 291.4 | 2,813.7 |

| Source 1: Climate averages for Canberra Airport Comparison (1939–2010); averages given are for 1991–2010[147][154] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Records from Canberra Airport for more recent extremes[155] | |||||||||||||

Urban structure

Canberra is a planned city and the inner-city area was originally designed by Walter Burley Griffin, a major 20th-century American architect.[156] Within the central area of the city near Lake Burley Griffin, major roads follow a wheel-and-spoke pattern rather than a grid.[157] Griffin's proposal had an abundance of geometric patterns, including concentric hexagonal and octagonal streets emanating from several radii.[157] However, the outer areas of the city, built later, are not laid out geometrically.[158]

Lake Burley Griffin was deliberately designed so that the orientation of the components was related to various topographical landmarks in Canberra.[159][160] The lakes stretch from east to west and divided the city in two; a land axis perpendicular to the central basin stretches from Capital Hill—the eventual location of the new Parliament House on a mound on the southern side—north northeast across the central basin to the northern banks along Anzac Parade to the Australian War Memorial.[100] This was designed so that looking from Capital Hill, the War Memorial stood directly at the foot of Mount Ainslie. At the southwestern end of the land axis was Bimberi Peak,[160] the highest mountain in the ACT, approximately 52 km (32 mi) south west of Canberra.[135]

The straight edge of the circular segment that formed the central basin of Lake Burley Griffin was perpendicular to the land axis and designated the water axis, and it extended northwest towards Black Mountain.[160] A line parallel to the water axis, on the northern side of the city, was designated the municipal axis.[161] The municipal axis became the location of Constitution Avenue, which links City Hill in Civic Centre and both Market Centre and the Defence precinct on Russell Hill. Commonwealth Avenue and Kings Avenue were to run from the southern side from Capital Hill to City Hill and Market Centre on the north respectively, and they formed the western and eastern edges of the central basin. The area enclosed by the three avenues was known as the Parliamentary Triangle, and formed the centrepiece of Griffin's work.[160][161]

The Griffins assigned spiritual values to Mount Ainslie, Black Mountain, and Red Hill and originally planned to cover each of these in flowers. That way each hill would be covered with a single, primary colour which represented its spiritual value.[162] This part of their plan never came to fruition, as World War I slowed construction and planning disputes led to Griffin's dismissal by Prime Minister Billy Hughes after the war ended.[82][83][163]

The urban areas of Canberra are organised into a hierarchy of districts, town centres, group centres, local suburbs as well as other industrial areas and villages. There are seven residential districts, each of which is divided into smaller suburbs, and most of which have a town centre which is the focus of commercial and social activities.[164] The districts were settled in the following chronological order:

- Canberra Central, mostly settled in the 1920s and 1930s, with expansion up to the 1960s,[165] 25 suburbs

- Woden Valley, first settled in 1964,[114] 12 suburbs

- Belconnen, first settled in 1966,[114] 27 suburbs (2 not yet developed)

- Weston Creek, settled in 1969, 8 suburbs[166]

- Tuggeranong, settled in 1974,[167] 18 suburbs

- Gungahlin, settled in the early 1990s, 18 suburbs (3 not yet developed)

- Molonglo Valley, development began in 2010, 13 suburbs planned.

The Canberra Central district is substantially based on Walter Burley Griffin's designs.[160][161][168] In 1967 the then National Capital Development Commission adopted the "Y Plan" which laid out future urban development in Canberra around a series of central shopping and commercial area known as the 'town centres' linked by freeways, the layout of which roughly resembled the shape of the letter Y,[169] with Tuggeranong at the base of the Y and Belconnen and Gungahlin located at the ends of the arms of the Y.[169]

Development in Canberra has been closely regulated by government,[170][171] both through planning processes and the use of crown lease terms that have tightly limited the use of parcels of land. Land in the ACT is held on 99-year crown leases from the national government, although most leases are now administered by the Territory government.[172] There have been persistent calls for constraints on development to be liberalised,[171] but also voices in support of planning consistent with the original 'bush capital' and 'urban forest' ideals that underpin Canberra's design.[173]

Many of Canberra's suburbs are named after former Prime Ministers, famous Australians, early settlers, or use Aboriginal words for their title.[174] Street names typically follow a particular theme; for example, the streets of Duffy are named after Australian dams and reservoirs, the streets of Dunlop are named after Australian inventions, inventors and artists and the streets of Page are named after biologists and naturalists.[174] Most diplomatic missions are located in the suburbs of Yarralumla, Deakin and O'Malley.[175] There are three light industrial areas: the suburbs of Fyshwick, Mitchell and Hume.[176]

| Points of Interest Looking South from Mount Ainslie | |||

Sustainability and the environment

The average Canberran was responsible for 13.7 tonnes of greenhouse gases in 2005.[178] In 2012, the ACT Government legislated greenhouse gas targets to reduce its emissions by 40 per cent from 1990 levels by 2020, 80 per cent by 2050, with no net emissions by 2060.[179] The government announced in 2013 a target for 90% of electricity consumed in the ACT to be supplied from renewable sources by 2020,[180] and in 2016 set an ambitious target of 100% by 2020.[181][182]

In 1996 Canberra became the first city in the world to set a vision of no waste, proposing an ambitious target of 2010 for completion.[183] The strategy aimed to achieve a waste-free society by 2010, through the combined efforts of industry, government and community.[184] By early 2010, it was apparent that though it had reduced waste going to landfill, the ACT initiative's original 2010 target for absolutely zero landfill waste would be delayed or revised to meet the reality.[185][186]

Plastic bags made of polyethylene polymer with a thickness of less than 35 μm were banned from retail distribution in the ACT from November 2011.[187][188][189] The ban was introduced by the ACT Government in an effort to make Canberra more sustainable.[188]

Of all waste produced in the ACT, 75 per cent is recycled.[190] Average household food waste in the ACT remains above the Australian average, costing an average $641 per household per annum.[191]

Canberra's annual Floriade festival features a large display of flowers every Spring in Commonwealth Park. The organisers of the event have a strong environmental standpoint, promoting and using green energy, "green catering", sustainable paper, the conservation and saving of water.[177] The event is also smoke-free.[177]

Government and politics

Territory government

and the statue Ethos (Tom Bass, 1961)

There is no local council or city government for the city of Canberra. The Australian Capital Territory Legislative Assembly performs the roles of both a city council for the city and a territory government for the rest of the Australian Capital Territory.[192] However, the vast majority of the population of the Territory reside in Canberra and the city is therefore the primary focus of the ACT Government.

The assembly consists of 25 members elected from five districts using proportional representation. The five districts are Brindabella, Ginninderra, Kurrajong, Murrumbidgee and Yerrabi, which each elect five members.[193] The Chief Minister is elected by the Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) and selects colleagues to serve as ministers alongside him or her in the Executive, known informally as the cabinet.[192]

Whereas the ACT has federally been dominated by Labor,[194][195] the Liberals have been able to gain some footing in the ACT Legislative Assembly and were in government during a period of 6+1⁄2 years from 1995 and 2001. Labor took back control of the Assembly in 2001.[121] At the 2004 election, Chief Minister Jon Stanhope and the Labor Party won 9 of the 17 seats allowing them to form the ACT's first majority government.[121] Since 2008, the ACT has been governed by a coalition of Labor and the Greens.[121][196][197] As of 2022[update], the Chief Minister was Andrew Barr from the Australian Labor Party.

The Australian federal government retains some influence over the ACT government. In the administrative sphere, most frequently this is through the actions of the National Capital Authority which is responsible for planning and development in areas of Canberra which are considered to be of national importance or which are central to Griffin's plan for the city,[198] such as the Parliamentary Triangle, Lake Burley Griffin, major approach and processional roads, areas where the Commonwealth retains ownership of the land or undeveloped hills and ridge-lines (which form part of the Canberra Nature Park).[198][199][200] The national government also retains a level of control over the Territory Assembly through the provisions of the Australian Capital Territory (Self-Government) Act 1988.[201] This federal act defines the legislative power of the ACT assembly.[202]

Federal representation

The ACT was given its first federal parliamentary representation in 1949 when it gained a seat in the House of Representatives, the Division of Australian Capital Territory.[203][204] However, the ACT member could only vote on matters directly affecting the territory.[204] In 1974, the ACT was allocated two Senate seats and the House of Representatives seat was divided into two.[203] A third was created in 1996, but was abolished in 1998 because of changes to the regional demographic distribution.[194] At the 2019 election, the third seat has been reintroduced as the Division of Bean.

The House of Representatives seats have mostly been held by Labor and usually by comfortable margins.[194][195] The Labor Party has polled at least seven percentage points more than the Liberal Party at every federal election since 1990 and their average lead since then has been 15 percentage points.[121] The ALP and the Liberal Party held one Senate seat each until the 2022 election when Independent candidate David Pocock unseated the Liberal candidate Zed Seselja.[205]

Judiciary and policing

The Australian Federal Police (AFP) provides all of the constabulary services in the territory in a manner similar to state police forces, under a contractual agreement with the ACT Government.[206] The AFP does so through its community policing arm ACT Policing.[207]

People who have been charged with offences are tried either in the ACT Magistrates Court or, for more severe offences, the ACT Supreme Court.[208] Prior to its closure in 2009, prisoners were held in remand at the Belconnen Remand Centre in the ACT but usually imprisoned in New South Wales.[209] The Alexander Maconochie Centre was officially opened on 11 September 2008 by then Chief Minister Jon Stanhope. The total cost for construction was $130 million.[210] The ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal deal with minor civil law actions and other various legal matters.[211][212]

Canberra has the lowest rate of crime of any capital city in Australia as of 2019[update].[213] As of 2016[update] the most common crimes in the ACT were property related crimes, unlawful entry with intent and motor vehicle theft. They affected 2,304 and 966 people (580 and 243 per 100,000 persons respectively). Homicide and related offences—murder, attempted murder and manslaughter, but excluding driving causing death and conspiracy to murder—affect 1.0 per 100,000 persons, which is below the national average of 1.9 per 100,000. Rates of sexual assault (64.4 per 100,000 persons) are also below the national average (98.5 per 100,000).[214][215][216] However the 2017 crime statistics showed a rise in some types of personal crime, notably burglaries, thefts and assaults.

Economy

In February 2020, the unemployment rate in Canberra was 2.9% which was lower than the national unemployment rate of 5.1%.[217] As a result of low unemployment and substantial levels of public sector and commercial employment, Canberra has the highest average level of disposable income of any Australian capital city.[218] The gross average weekly wage in Canberra is $1827 compared with the national average of $1658 (November 2019).[219]

The median house price in Canberra as of February 2020 was $745,000, lower than only Sydney among capital cities of more than 100,000 people, having surpassed Melbourne and Perth since 2005.[219][220][221] The median weekly rent paid by Canberra residents is higher than rents in all other states and territories.[222] As of January 2014 the median unit rent in Canberra was $410 per week and median housing rent was $460, making the city the third most expensive in the country.[223] Factors contributing to this higher weekly rental market include; higher average weekly incomes, restricted land supply,[224] and inflationary clauses in the ACT Residential Tenancies Act.[225]

The city's main industry is public administration and safety, which accounted for 27.1% of Gross Territory Product in 2018-19 and employed 32.49% of Canberra's workforce.[226][21] The headquarters of many Australian Public Service agencies are located in Canberra, and Canberra is also host to several Australian Defence Force establishments, most notably the Australian Defence Force headquarters and HMAS Harman, which is a naval communications centre that is being converted into a tri-service, multi-user depot.[227] Other major sectors by employment include Health Care (10.54%), Professional Services (9.77%), Education and Training (9.64%), Retail (7.27%), Accommodation & Food (6.39%) and Construction (5.80%).

The former RAAF Fairbairn, adjacent to the Canberra Airport was sold to the operators of the airport,[228] but the base continues to be used for RAAF VIP flights.[229][230] A growing number of software vendors have based themselves in Canberra, to capitalise on the concentration of government customers; these include Tower Software and RuleBurst.[231][232] A consortium of private and government investors is making plans for a billion-dollar data hub, with the aim of making Canberra a leading centre of such activity in the Asia-Pacific region.[233] A Canberra Cyber Security Innovation Node was established in 2019 to grow the ACT's cyber security sector and related space, defence and education industries.[234]

Demographics

At the 2021 census, the population of Canberra was 453,558,[235] up from 395,790 at the 2016 census,[236] and 355,596 at the 2011 census.[237] Canberra has been the fastest-growing city in Australia in recent years, having grown 23.3% from 2011 to 2021.[235]

Canberrans are relatively young, highly mobile and well educated. The median age is 35 years and only 12.7% of the population is aged over 65 years.[236] Between 1996 and 2001, 61.9% of the population either moved to or from Canberra, which was the second highest mobility rate of any Australian capital city.[238] As at May 2017, 43% of ACT residents (25–64) had a level of educational attainment equal to at least a bachelor's degree, significantly higher that the national average of 31%.[239]

According to statistics collected by the National Australia Bank and reported in The Canberra Times, Canberrans on average give significantly more money to charity than Australians in other states and territories, for both dollar giving and as a proportion of income.[240]

Ancestry and immigration

| Birthplace[N 1] | Population |

|---|---|

| Australia | 269,682 |

| England | 12,739 |

| Mainland China | 11,334 |

| India | 10,405 |

| New Zealand | 4,722 |

| Philippines | 3,789 |

| Vietnam | 3,340 |

| United States | 2,775 |

| Sri Lanka | 2,774 |

| Malaysia | 2,431 |

| South Korea | 2,283 |

At the 2016 census, the most commonly nominated ancestries were:[N 2][22]

The 2016 census showed that 32% of Canberra's inhabitants were born overseas.[22] Of inhabitants born outside Australia, the most prevalent countries of birth were England, China, India, New Zealand and the Philippines.[242]

1.6% of the population, or 6,476 people, identified as Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders) in 2016.[N 5][22]

Language

At the 2016 census, 72.7% of people spoke only English at home. The other languages most commonly spoken at home were Mandarin (3.1%), Vietnamese (1.1%), Cantonese (1%), Hindi (0.9%) and Spanish (0.8%).[22]

Religion

On census night in 2016, approximately 50.0% of ACT residents described themselves as Christian (excluding not stated responses), the most common denominations being Catholic and Anglican; 36.2% described themselves as having no religion.[236]

Culture

Education

The two main tertiary institutions are the Australian National University (ANU) in Acton and the University of Canberra (UC) in Bruce, with over 10,500 and 8,000 full-time-equivalent students respectively.[243][244] Established in 1946,[245] the ANU has always had a strong research focus and is ranked among the leading universities in the world and the best in Australia by The Times Higher Education Supplement and the Shanghai Jiao Tong World University Rankings.[244][246] There are two religious university campuses in Canberra: Signadou in the northern suburb of Watson is a campus of the Australian Catholic University;[247] St Mark's Theological College in Barton is part of the secular Charles Sturt University.[248] The ACT Government announced on 5 March 2020 that the CIT campus and an adjoining carpark in Reid would be leased to the University of New South Wales (UNSW) for a peppercorn lease, for it to develop as a campus for a new UNSW Canberra.[249] UNSW released a master plan in 2021 for a 6,000 student campus to be realised over 15 years at a cost of $1 billion.[250]

The Australian Defence College has two campuses: the Australian Command and Staff College (ACSC) plus the Centre for Defence and Strategic Studies (CDSS) at Weston, and the Australian Defence Force Academy (ADFA) beside the Royal Military College, Duntroon located in the inner-northern suburb of Campbell.[251][252] ADFA teaches military undergraduates and postgraduates and includes UNSW@ADFA, a campus of the University of New South Wales;[253][254] Duntroon provides Australian Army officer training.[255]

Tertiary level vocational education is also available through the Canberra Institute of Technology (CIT), with campuses in Bruce, Reid, Gungahlin, Tuggeranong and Fyshwick.[256] The combined enrolment of the CIT campuses was over 28,000 students in 2019.[257] Following the transfer of land in Reid for the new UNSW Canberra, a new CIT Woden is scheduled to be completed by 2025.[258]

In 2016 there were 132 schools in Canberra; 87 were operated by the government and 45 were private.[259] During 2006, the ACT Government announced closures of up to 39 schools, to take effect from the end of the school year, and after a series of consultations unveiled its Towards 2020: Renewing Our Schools policy.[260] As a result, some schools closed during the 2006–08 period, while others were merged; the creation of combined primary and secondary government schools was to proceed over a decade. The closure of schools provoked significant opposition.[261][262][263] Most suburbs were planned to include a primary and a nearby preschool; these were usually located near open areas where recreational and sporting activities were easily available.[264] Canberra also has the highest percentage of non-government (private) school students in Australia, accounting for 40.6 per cent of ACT enrollments.[265]

Arts and entertainment

Canberra is home to many national monuments and institutions such as the Australian War Memorial, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, the National Gallery of Australia, the National Portrait Gallery, the National Library,[168] the National Archives,[266] the Australian Academy of Science,[267] the National Film & Sound Archive and the National Museum.[168] Many Commonwealth government buildings in Canberra are open to the public, including Parliament House, the High Court and the Royal Australian Mint.[268][269][270]

Lake Burley Griffin is the site of the Captain James Cook Memorial and the National Carillon.[168] Other sites of interest include the Australian–American Memorial, Commonwealth Park, Commonwealth Place, the Telstra Tower, the Australian National Botanic Gardens, the National Zoo and Aquarium, the National Dinosaur Museum, and Questacon – the National Science and Technology Centre.[168][271]

The Canberra Museum and Gallery in the city is a repository of local history and art, housing a permanent collection and visiting exhibitions.[272] Several historic homes are open to the public: Lanyon and Tuggeranong Homesteads in the Tuggeranong Valley,[273][274] Mugga-Mugga in Symonston,[275] and Blundells' Cottage in Parkes all display the lifestyle of the early European settlers.[39] Calthorpes' House in Red Hill is a well-preserved example of a 1920s house from Canberra's very early days.[276] Strathnairn Homestead is an historic building which also dates from the 1920s.

Canberra has many venues for live music and theatre: the Canberra Theatre and Playhouse which hosts many major concerts and productions;[277] and Llewellyn Hall (within the ANU School of Music), a world-class concert hall are two of the most notable.[278] The Street Theatre is a venue with less mainstream offerings.[278] The Albert Hall was the city's first performing arts venue, opened in 1928. It was the original performance venue for theatre groups such as the Canberra Repertory Society.[279]

Stonefest was a large annual festival, for some years one of the biggest festivals in Canberra.[280][281] It was downsized and rebranded as Stone Day in 2012.[282] There are numerous bars and nightclubs which also offer live entertainment, particularly concentrated in the areas of Dickson, Kingston and the city.[283] Most town centres have facilities for a community theatre and a cinema, and they all have a library.[284] Popular cultural events include the National Folk Festival, the Royal Canberra Show, the Summernats car festival, Enlighten festival, the National Multicultural Festival in February and the Celebrate Canberra festival held over 10 days in March in conjunction with Canberra Day.[285]

Canberra maintains sister-city relationships with both Nara, Japan and Beijing, China. Canberra has friendship-city relationships with both Dili, East Timor and Hangzhou, China.[286] City-to-city relationships encourage communities and special interest groups both locally and abroad to engage in a wide range of exchange activities. The Canberra Nara Candle Festival held annually in spring, is a community celebration of the Canberra Nara Sister City relationship.[287] The festival is held in Canberra Nara Park on the shores of Lake Burley Griffin.[288]

The history of Canberra was told in the 1938 radio feature Canberra the Great.

Media

As Australia's capital, Canberra is the most important centre for much of Australia's political reportage and thus all the major media, including the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, the commercial television networks, and the metropolitan newspapers maintain local bureaus. News organisations are represented in the press gallery, a group of journalists who report on the national parliament. The National Press Club of Australia in Barton has regular television broadcasts of its lunches at which a prominent guest, typically a politician or other public figure, delivers a speech followed by a question-and-answer session.[289]

Canberra has a daily newspaper, The Canberra Times, which was established in 1926.[290][291] There are also several free weekly publications, including news magazines CityNews and Canberra Weekly as well as entertainment guide BMA Magazine. BMA Magazine first went to print in 1992; the inaugural edition featured coverage of the Nirvana Nevermind tour.[292]

There are a number of AM and FM stations broadcasting in Canberra (AM/FM Listing). The main commercial operators are the Capital Radio Network (2CA and 2CC), and Austereo/ARN (104.7 and Mix 106.3). There are also several community operated stations.

A DAB+ digital radio trial is also in operation, it simulcasts some of the AM/FM stations, and also provides several digital only stations (DAB+ Trial Listing).

Five free-to-air television stations service Canberra:

- ABC Canberra (ABC)

- SBS New South Wales (SBS)

- Southern Cross 10 Southern NSW & ACT (CTC) – Network 10 affiliate

- Seven Network Southern NSW & ACT (CBN) – Seven Network owned and operated station

- WIN Television Southern NSW & ACT (WIN) – Nine Network affiliate

Each station broadcasts a primary channel and several multichannels. Of the three main commercial networks:

- WIN airs a half-hour local WIN News each weeknight at 6pm, produced from a newsroom in the city and broadcast from studios in Wollongong.

- Southern Cross 10 airs short local news updates throughout the day, produced and broadcast from its Hobart studios. It previously aired a regional edition of Nine News from Sydney each weeknight at 6pm, featuring opt-outs for Canberra and the ACT when it was a Nine affiliate.

- Seven airs short local news and weather updates throughout the day, produced and broadcast from its Canberra studios.

Prior to 1989, Canberra was serviced by just the ABC, SBS and Capital Television (CTC), which later became Ten Capital in 1994 then Southern Cross Ten in 2002 then Channel 9/Southern Cross Nine in 2016 and finally Channel 10 in 2021, with Prime Television (now Prime7) and WIN Television arriving as part of the Government's regional aggregation program in that year.[293]

Pay television services are available from Foxtel (via satellite) and telecommunications company TransACT (via cable).[294]

Sport

In addition to local sporting leagues, Canberra has a number of sporting teams that compete in national and international competitions. The best known teams are the Canberra Raiders and the ACT Brumbies who play rugby league and rugby union respectively; both have been champions of their leagues.[295][296] Both teams play their home games at Canberra Stadium,[297] which is the city's largest stadium and was used to hold group matches in football for the 2000 Summer Olympics and in rugby union for the 2003 Rugby World Cup.[298][299]

Canberra United represents the city in the A-League Women (formerly the W-League), the national women's soccer league and were champions in the 2011–12 season.[300] A men's team is set to join the A-League Men in the 2024–25 season.

The city also has a successful basketball team, the Canberra Capitals, which has won seven out of the last eleven national women's basketball titles.[301] The Canberra Vikings represent the city in the National Rugby Championship and finished second in the 2015 season.

There are also teams that participate in national competitions in netball, field hockey, ice hockey, cricket and baseball.

The historic Prime Minister's XI cricket match is played at Manuka Oval annually.[302] Other significant annual sporting events include the Canberra Marathon[303] and the City of Canberra Half Ironman Triathlon.

Canberra has been bidding for an Australian Football League club since 1981 when Australian rules in the Australian Capital Territory was more popular.[304] While the league has knocked back numerous proposals, according to the AFL Canberra belongs to the Greater Western Sydney Giants[305] who play three home games at Manuka Oval each season.

Other significant annual sporting events include the Canberra Marathon[303] and the City of Canberra Half Ironman Triathlon.

The Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) is located in the Canberra suburb of Bruce.[306] The AIS is a specialised educational and training institution providing coaching for elite junior and senior athletes in a number of sports. The AIS has been operating since 1981 and has achieved significant success in producing elite athletes, both local and international.[306] The majority of Australia's team members and medallists at the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney were AIS graduates.[307]

Canberra has numerous sporting ovals, golf courses, skate parks, and swimming pools that are open to the public. Tennis courts include those at the National Sports Club, Lyneham, former home of the Canberra Women's Tennis Classic. A Canberra-wide series of bicycle paths are available to cyclists for recreational and sporting purposes. Canberra Nature Parks have a large range of walking paths, horse and mountain bike trails. Water sports like sailing, rowing, dragon boating and water skiing are held on Canberra's lakes.[308][309] The Rally of Canberra is an annual motor sport event, and from 2000 to 2002, Canberra hosted the Canberra 400 event for V8 Supercars on the temporary Canberra Street Circuit, which was located inside the Parliamentary Triangle.

A popular form of exercise for people working near or in the Parliamentary Triangle is to do the "bridge to bridge walk/run" of about 5 km around Lake Burley Griffin, crossing the Commonwealth Avenue Bridge and Kings Avenue Bridge, using the paths beside the lake. The walk takes about 1 hour, making it ideal for a lunchtime excursion. This is also popular on weekends. Such was the popularity during the COVID-19 isolation in 2020 that the ACT Government initiated a 'Clockwise is COVID-wise' rule for walkers and runners.[310]

Infrastructure

Health

Canberra has two large public hospitals, the approximately 600-bed Canberra Hospital—formerly the Woden Valley Hospital—in Garran and the 174-bed Calvary Public Hospital in Bruce. Both are teaching institutions.[311][312][313][314] The largest private hospital is the Calvary John James Hospital in Deakin.[315][316] Calvary Private Hospital in Bruce and Healthscope's National Capital Private Hospital in Garran are also major healthcare providers.[311][313]

The Royal Canberra Hospital was located on Acton Peninsula on Lake Burley Griffin; it was closed in 1991 and was demolished in 1997 in a controversial and fatal implosion to facilitate construction of the National Museum of Australia.[110][161][168][317][318] The city has 10 aged care facilities. Canberra's hospitals receive emergency cases from throughout southern New South Wales,[319] and ACT Ambulance Service is one of four operational agencies of the ACT Emergency Services Authority.[320] NETS provides a dedicated ambulance service for inter-hospital transport of sick newborns within the ACT and into surrounding New South Wales.[321]

Transport

The automobile is by far the dominant form of transport in Canberra.[322] The city is laid out so that arterial roads connecting inhabited clusters run through undeveloped areas of open land or forest, which results in a low population density;[323] this also means that idle land is available for the development of future transport corridors if necessary without the need to build tunnels or acquire developed residential land. In contrast, other capital cities in Australia have substantially less green space.[324]

Canberra's districts are generally connected by parkways—limited access dual carriageway roads[322][325] with speed limits generally set at a maximum of 100 km/h (62 mph).[326][327] An example is the Tuggeranong Parkway which links Canberra's CBD and Tuggeranong, and bypasses Weston Creek.[328] In most districts, discrete residential suburbs are bounded by main arterial roads with only a few residential linking in, to deter non-local traffic from cutting through areas of housing.[329]

In an effort to improve road safety, traffic cameras were first introduced to Canberra by the Kate Carnell Government in 1999.[330] The traffic cameras installed in Canberra include fixed red-light and speed cameras and point-to-point speed cameras; together they bring in revenue of approximately $11 million per year in fines.[330]

ACTION, the government-operated bus service, provides public transport throughout the city.[331] CDC Canberra provides bus services between Canberra and nearby areas of New South Wales of (Murrumbateman and Yass)[332] and as Qcity Transit (Queanbeyan).[333] A light rail line commenced service on 20 April 2019 linking the CBD with the northern district of Gungahlin.[334] A planned Stage 2A of Canberra's light rail network will run from Alinga Street station to Commonwealth Park, adding three new stops at City West, City South and Commonwealth Park.[335] In February 2021 ACT Minister for Transport and City Services Chris Steel said he expects construction on Stage 2A to commence in the 2021-22 financial year, and for "tracks to be laid" by the next Territory election in 2024.[336] At the 2016 census, 7.1% of the journeys to work involved public transport, while 4.5% walked to work.[236]

There are two local taxi companies. Aerial Capital Group enjoyed monopoly status until the arrival of Cabxpress in 2007.[337] In October 2015 the ACT Government passed legislation to regulate ride sharing, allowing ride share services including Uber to operate legally in Canberra.[338][339][340] The ACT Government was the first jurisdiction in Australia to enact legislation to regulate the service.[341] Since then many other ride sharing and taxi services have started in ACT namely Ola, Glide Taxi[342] and GoCatch[343]

An interstate NSW TrainLink railway service connects Canberra to Sydney.[344] Canberra railway station is in the inner south suburb of Kingston.[345] Between 1920 and 1922 the train line crossed the Molonglo River and ran as far north as the city centre, although the line was closed following major flooding and was never rebuilt, while plans for a line to Yass were abandoned. A 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge construction railway was built in 1923 between the Yarralumla brickworks and the provisional Parliament House; it was later extended to Civic, but the whole line was closed in May 1927.[346] Train services to Melbourne are provided by way of a NSW TrainLink bus service which connects with a rail service between Sydney and Melbourne in Yass, about a one-hour drive from Canberra.[344][347]

Plans to establish a high-speed rail service between Melbourne, Canberra and Sydney,[348] have not been implemented, as the various proposals have been deemed economically unviable.[349][350] The original plans for Canberra included proposals for railed transport within the city,[351] however none eventuated.[351] The phase 2 report of the most recent proposal, the High Speed Rail Study, was published by the Department of Infrastructure and Transport on 11 April 2013.[352] A railway connecting Canberra to Jervis Bay was also planned but never constructed.[353]

Canberra is about three hours by road from Sydney on the Federal Highway (National Highway 23),[354] which connects with the Hume Highway (National Highway 31) near Goulburn, and seven hours by road from Melbourne on the Barton Highway (National Highway 25), which joins the Hume Highway at Yass.[354] It is a two-hour drive on the Monaro Highway (National Highway 23) to the ski fields of the Snowy Mountains and the Kosciuszko National Park.[347] Batemans Bay, a popular holiday spot on the New South Wales coast, is also two hours away via the Kings Highway.[347]

Canberra Airport provides direct domestic services to Adelaide, Brisbane, Cairns, Darwin, Gold Coast, Hobart, Melbourne, Perth, Sunshine Coast and Sydney with connections to other domestic centres.[355] There are also direct flights to small regional towns: Ballina, Dubbo, Newcastle and Port Macquarie in New South Wales. Canberra Airport is, as of September 2013, designated by the Australian Government Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development as a restricted use designated international airport.[356] International flights have previously been operated by both Singapore Airlines and Qatar Airways. Fiji Airways has announced direct flights to Nadi commencing in July 2023.[357] Until 2003 the civilian airport shared runways with RAAF Base Fairbairn. In June of that year, the Air Force base was decommissioned and from that time the airport was fully under civilian control.[358]

Canberra has one of the highest rates of active travel of all Australian major cities, with 7.1 per cent of commuters walking or cycling to work in 2011.[359] An ACT Government survey conducted in late 2010 found that Canberrans walk an average of 26 minutes each day.[360] According to The Canberra Times in March 2014, Canberra's cyclists are involved in an average of four reported collisions every week.[361] The newspaper also reported that Canberra is home to 87,000 cyclists, translating to the highest cycling participation rate in Australia; and, with higher popularity, bike injury rates in 2012 were twice the national average.[362]

Since late 2020, two scooter-sharing systems have been operational in Canberra: orange scooters from Neuron Mobility and purple scooters from Beam Mobility,[363] both Singapore-based companies that operate in many Australian cities. These services cover much of Canberra Central and Central Belconnen, with plans to expand coverage to more areas of the city in 2022.[364]

Utilities

The government-owned Icon Water manages Canberra's water and sewerage infrastructure.[366] ActewAGL is a joint venture between ACTEW and AGL, and is the retail provider of Canberra's utility services including water, natural gas, electricity, and also some telecommunications services via a subsidiary TransACT.[367]

Canberra's water is stored in four reservoirs, the Corin, Bendora and Cotter dams on the Cotter River and the Googong Dam on the Queanbeyan River. Although the Googong Dam is located in New South Wales, it is managed by the ACT government.[368] Icon Water owns Canberra's two wastewater treatment plants, located at Fyshwick and on the lower reaches of the Molonglo River.[369][370]

Electricity for Canberra mainly comes from the national power grid through substations at Holt and Fyshwick (via Queanbeyan).[371] Power was first supplied from the Kingston Powerhouse near the Molonglo River, a thermal plant built in 1913, but this was finally closed in 1957.[372][373] The ACT has four solar farms, which were opened between 2014 and 2017: Royalla (rated output of 20 megawatts, 2014),[374] Mount Majura (2.3 MW, 2016),[365] Mugga Lane (13 MW, 2017)[375] and Williamsdale (11 MW, 2017).[376] In addition, numerous houses in Canberra have photovoltaic panels or solar hot water systems. In 2015 and 2016, rooftop solar systems supported by the ACT government's feed-in tariff had a capacity of 26.3 megawatts, producing 34,910 MWh. In the same year, retailer-supported schemes had a capacity of 25.2 megawatts and exported 28,815 MWh to the grid (power consumed locally was not recorded).[377]

There are no wind-power generators in Canberra, but several have been built or are being built or planned in nearby New South Wales, such as the 140.7 megawatt Capital Wind Farm. The ACT government announced in 2013 that it was raising the target for electricity consumed in the ACT to be supplied from renewable sources to 90% by 2020,[180] raising the target from 210 to 550 megawatts.[378] It announced in February 2015 that three wind farms in Victoria and South Australia would supply 200 megawatts of capacity; these are expected to be operational by 2017.[379] Contracts for the purchase of an additional 200 megawatts of power from two wind farms in South Australia and New South Wales were announced in December 2015 and March 2016.[380][381] The ACT government announced in 2014 that up to 23 megawatts of feed-in-tariff entitlements would be made available for the establishment of a facility in the ACT or surrounding region for burning household and business waste to produce electricity by 2020.[382]

The ACT has the highest rate with internet access at home (94 per cent of households in 2014–15).[383]

Twin towns and sister cities

Canberra has three sister cities:

In addition, Canberra has the following friendship cities:

- Hangzhou, China: The ACT Government signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Hangzhou Municipal People's Government on 29 October 1998. The Agreement was designed to promote business opportunities and cultural exchanges between the two cities.[385]

- Dili, East Timor: The Canberra Dili Friendship Agreement was signed in 2004, aiming to build friendship and mutual respect and promote educational, cultural, economic, humanitarian and sporting links between Canberra and Dili.[386]

See also

- 1971 Canberra flood

- 2003 Canberra bushfires

- List of planned cities

- List of tallest buildings in Canberra

- Lists of capitals

Notes

- ^ In accordance with the Australian Bureau of Statistics source, England, Scotland, Mainland China and the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau are listed separately

- ^ As a percentage of 373,561 persons who nominated their ancestry at the 2016 census.

- ^ The Australian Bureau of Statistics has stated that most who nominate "Australian" as their ancestry are part of the Anglo-Celtic group.[241]

- ^ Of any ancestry. Includes those identifying as Aboriginal Australians or Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

- ^ Of any ancestry. Includes those identifying as Aboriginal Australians or Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

References

Citations

- ^ a b "Regional population, 2022-23". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 26 March 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "GFS / BOM data for CANBERRA AIRPORT". Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ a b "Planning Data Statistics". ACT Planning & Land Authority. 21 July 2009. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between CANBERRA and SYDNEY". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between CANBERRA and MELBOURNE". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between CANBERRA and ADELAIDE". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between CANBERRA and BRISBANE". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between CANBERRA and PERTH". Geoscience Australia. March 2004. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ Augmented Electoral Commission for the Australian Capital Territory (July 2018). "Redistribution of the Australian Capital Territory into electoral divisions" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

The electoral divisions described in this report came into effect from Friday 13 July 2018 ... However, members of the House of Representatives will not represent or contest these electoral divisions until ... a general election.

- ^ "Canberra map". Britannica. 2013. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ a b Flood, J. M.; David, B.; Magee, J.; English, B. (1987), "Birrigai: a Pleistocene site in the south eastern highlands", Archaeology in Oceania, 22: 9–22, doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.1987.tb00159.x

- ^ a b "Community Stories: Canberra Region". National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ a b Davison, Graeme; Hirst, John; Macintyre, Stuart, eds. (1998). The Oxford Companion to Australian History. Oxford University Press. pp. 464–465, 662–663. ISBN 9780195535976.

- ^ Nowroozi, Isaac (19 February 2021). "Celebrating Marion Mahony Griffin, the woman who helped shape Canberra". ABC News. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ Lewis, Wendy; Balderstone, Simon; Bowan, John (2006). Events That Shaped Australia. New Holland. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-74110-492-9.

- ^ a b "Canberra ranked 'best place to live' by OECD". BBC News. 8 October 2014. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Riordan, Primrose (7 October 2014). "Canberra named the best place in the world...again". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Why Canberra is Australia's most liveable city". Switzer Daily. 4 February 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ a b "'Criminally overlooked': Canberra named third-best travel city in the world". ABC News. 24 October 2017. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Lonely Planet lists Canberra as one of the world's three hottest destinations". The Guardian. 24 October 2017. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ a b c "EDA ACT Economic Indicators". EDA Australia. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "2016 Census Community Profiles: Australian Capital Territory". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ "Canberra blooms: Australia's biggest celebration of spring - People's Daily Online". en.people.cn. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Floriade - the biggest blooming show in Australia". Australian Traveller. 5 September 2014. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ a b Osborne, Tegan (3 April 2016). "What is the Aboriginal history of Canberra?". ABC News. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ "Ngambri people consider claiming native title over land in Canberra after ACT government apologises". ABC News. 29 April 2023. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

The name 'Canberra' is derived from the name of our people and country: the Ngambri, the Kamberri.

- ^ a b c Selkirk, Henry (1923). "The Origins of Canberra". The Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. 9: 49–78. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ Cambage, Richard Hind (1919). "Part X, The Federal Capital Territory". Notes on the Native Flora of New South Wales. Linnean Society of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ^ "A Skull Where Once The Native Roamed". The Canberra Times. Vol. 37, no. 10,610. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 9 August 1963. p. 2. Retrieved 23 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Frei, Patricia. "Discussion on the Meaning of 'Canberra'". Canberra History Web. Patricia Frei. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ Hull, Crispin (6 February 2009). "European settlement and the naming of Canberra". Canberra – Australia's National Capital. Crispin Hull. Archived from the original on 26 April 2010. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ "Suggested names for Australia's new capital | naa.gov.au". www.naa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Australia For Everyone: Canberra - The Names of Canberra". Australia Guide. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Salvage, Jess (25 August 2016). "The Siting and Naming of Canberra". www.nca.gov.au. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ a b "ABORIGINES ADVISED AINSLIE TO CHOOSE DUNTROON". The Canberra Times. Vol. 28, no. 3, 213. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 30 April 1954. p. 2. Retrieved 24 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "CANBERRA BLACKS". Sydney Morning Herald. No. 27, 886. New South Wales, Australia. 21 May 1927. p. 11. Retrieved 24 May 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b c d Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Trail (PDF). Australian National University.

- ^ Gillespie, Lyall (1984). Aborigines of the Canberra Region. Canberra: Wizard (Lyall Gillespie). pp. 1–25. ISBN 0-9590255-0-2.

- ^ a b "Blundells Cottage". National Capital Authority. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ a b Cambage, R.H. (1921). "Exploration between the Wingecarribee, Shoalhaven, Macquarie and Murrumbidgee Rivers". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. 7 (5): 217–288. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ Canberra – Australia's capital city, Australian Government, 4 February 2010, archived from the original on 12 February 2014

- ^ Fitzgerald 1987, p. 5.

- ^ Gillespie 1991, pp. 3–8.

- ^ Currie, Mark John (1823), Journal of an excursion to the southward of Lake George in New South Wales, nla.obj-62444232, retrieved 24 May 2022 – via Trove

- ^ Gillespie 1991, p. 9.

- ^ "LETTERS". Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 31 January 1934. p. 6. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ Gibbney 1988, p. 48.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1987, p. 9.