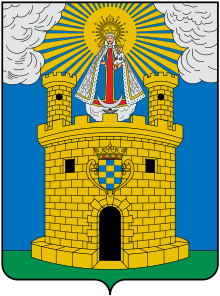

Coat of arms of Medellín (Colombia)

| Coat of arms of Medellín | |

|---|---|

| |

| Armiger | City and Municipality of Medellín |

| Adopted | March 31, 1678 |

| Shield | "In a field of azure, a round keep of gold, rounded and clarified of sable, charged with a shield of 15 pieces, 7 blue and 8 gold (arms of the house of Portocarrero), stamped with an ancient crown of gold, and surmounted, between its two turrets, by the image of Our Lady of Candelaria carrying the Child, in his left arm, and a candle in his right hand, with clouds rising from each canton."[note 1] |

| Use |

|

The coat of arms of Medellín is the heraldic emblem that represents the Colombian city of Medellín, capital of the department of Antioquia. It has its origin in the concession of its use by King Charles II of Spain by means of the Royal Decree given in Madrid on March 31, 1678.[1] The escutcheon also recalled in some of its elements the ancient coat of arms of the Spanish town of Medellín, in Extremadura, from which the city takes its name.[2]

The coat of arms, together with the flag and the anthem, are recognized as official symbols of the municipality of Medellín according to Decree No. 151 of February 20, 2002.[3] In addition, the escutcheon as a symbol of the city is part of the institutional image of the municipal administration, which is why it is present in ceremonial acts, on official stationery, in street furniture or in public works, although there are different stylistic versions between the City Hall and the Municipal council.

The escutcheon was also adopted by other entities such as the Archdiocese of Medellín, differentiated by the archbishop's cross on the seal and the name of the archdiocese as the motto.[1] Likewise, the arms of the city are also present in the first quarter of the emblem of the University of Medellín.[4]

History[edit]

On March 2, 1616, the visitor Francisco de Herrera Campuzano established the "Poblado de San Lorenzo" (Spanish for "Village of San Lorenzo") in the south of the Aburrá Valley, where El Poblado Park is today, with the function of serving as a shelter for the indigenous people.[5] Over time, the Aburrá Valley became a pantry to supply the workers of the gold mines located in the northeast of the Antioquia Province. In addition, due to its strategic position, between the mining region and the city of Antioquia, which at that time was the capital of the province, and due to the increase in population, the construction of a new town was arranged, since the indigenous reservation of San Lorenzo was discarded.[5][note 2]

Finally, in 1646, the new settlement was established in the angle formed by the Medellín River (formerly Aburrá) and the Santa Elena stream, a place called Sitio de Aná by the natives and Aguasal by the Spaniards.[5] In 1649, the new hamlet began to be called Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria de Aná (Spanish for "Our Lady of Candle of Aná"), a name that arose after the construction of the first church of walls and tiles consecrated to the Virgin of Candelaria.[5]

Since 1670, the inhabitants of the town of Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria de Aná began to want a town council, which implied administrative autonomy from the city of Antioquia. On March 20, 1671, Francisco de Montoya y Salazar, governor of the province, decreed the foundation of the town in the Sitio de Aná.[6] This foundation did not have the effect that a royal decree could have, and the inhabitants of the city of Antioquia opposed it, as they sensed that their preponderant role would be diminished with the establishment of that village as a town, for which reason they sought confirmation of the foundation through a royal concession. After overcoming various vicissitudes, finally in 1675 came the Royal Certificate of Foundation signed by the Queen Regent, Doña Mariana of Austria on behalf of her son, Charles II, and dated November 22, 1674. On November 2, 1675, the governor and captain general of the Province of Antioquia, Miguel de Aguinaga y Mendigoitía, formally proclaimed the creation of the Villa de Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria de Medellín (Spanish for "Town of Our Lady of Candles of Medellín"). The name Medellín was given in homage to Don Pedro Portocarrero y Aragón,[note 3] Count of Medellín in Extremadura, and then president of the Council of the Indies, for the interest he took in approving the erection of the new Town.[7][8][9]

On June 25, 1676, Governor Miguel de Aguinaga informed the crown about the compliance with the Royal Decree and how the erection was carried out.[10] Likewise, on June 24, 1676, the town council of the new town sent a report to His Majesty on the same subject, and after submitting several reports and making several requests, they referred to the coat of arms in the following terms:

"We also beg Your Majesty to grant arms to this town for the luster of it as the others have, as for the duration, this town promises much because the temper is very appreciable between summer and winter in the manner of the spring of Spain...".[10]

The document continues with a detailed description of the sanitation of the land, the mention of the Aburrá River (today the Medellín River), the richness of its minerals, the abundance of livestock and fruits of the land, the population at that time of approximately 4,000 souls and commerce. Later on about the Planta de Villa where they inform and describe the characteristics of the town, they say:

"...this under the patronage of Our Lady of Candles, a very miraculous image..."[10]

And further on they say;

"...the Candelaria has been the torch that has given light to its foundation..."[10]

Thus, the deep-rootedness and fervor that they had for this Marian devotion became evident.

After all this documentation sent to the crown, on February 9, 1678, the Council of the Indies agreed to grant the new town the same arms of Medellín Extremadura, also ratified the title of town and prohibited for 10 years, that the inhabitants of the city of Antioquia moved to the Villa de la Candelaria, thus avoiding that the city remained uninhabited.

This old drawing of the arms of Medellín, of naive characteristics, is a copy of the original drawing that came integrated in the Royal Decree, erroneously several publications indicate it as the original.

The document refers in the following terms:[11]

Privilege of Arms

From Messrs. Conde, Valdés, Santelize Guevara, Ochoa.

Council, February 9, 1678.

Having made relation the Royal Town Council of all the letters, reports and testimonies (relative) to the new foundation of the Villa de Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria de Medellín, of which the Governor Don Miguel de Aguinaga gives a very minor account in letter of June 25, 1676, it was agreed that all that was worked in this matter by the said Governor be approved, dispatching the title of Town, with the same arms that the one of Medellín has in the Province of Extremadura, and that the offices of Republic are enjoyed by the people who are exercising them for their life, and then they remain so that they benefit on account of the Royal Treasury with the quality that they are renounceable, like the others of the cities, towns and places of the Indies and that the own ones that are proposed for the public expenses are confirmed.

And that for a period of ten years no residents of Antioquia be admitted, and that the notary who has been appointed be granted a notary's office to be able to exercise his offices.

And that regarding the jurisdiction that is requested for this town, the Audiences of Santafé and Quito and the Governors of the Provinces of Antioquia and Popayán inform so that with greater knowledge they can take the appropriate resolution.

(There is a rubric).

(In the margin): Agreed of the Council of February 9, 1678 on the Villa de Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria de Medellín.

However, the use of this escutcheon was brief, since a new Royal Decree granted by King Charles II of Spain and given in Madrid on March 31, 1678, granted a new coat of arms that would be definitive:[1][12]

...A shield field blue and on it a very thick tower, round, all around crenellated and on it a coat of arms that has fifteen laces, seven blue and eight gold, and on its colonel that touches it and in the homage of the tower to each of the sides a turret, likewise crenellated and in the middle of them placed an image of Our Lady on a cloud, with her son in her arms with the invocation of the Annunciation in the form that follows.

The first coat of arms is still mentioned by Oidor Juan Antonio Mon y Velarde in the constitution he gave to the Town Council of Medellín in which he summarizes the genesis of the town and in which he says: "The town was also granted the right to use the same arms, privileges, extensions and pre-eminences that the town of Medellín enjoys in the Province of Extremadura in the kingdoms of Spain, but since the coat of arms of the Royal Decree has not been requested, the arms referred to therein have not been requested".[13]

But with the passage of time this coat of arms was completely forgotten. Meanwhile, the Villa de la Candelaria de Medellín (Spanish for "Town of the Candelaria of Medellín") was acquiring greater importance being declared "City" in 1813 and designated capital of the province in 1826, displacing the city of Antioquia, the same that opposed its raising to town.

Recovery of the heraldic memory[edit]

In 1952, the historian and heraldist Enrique Ortega Ricaurte, at that time director of the National Archive of Colombia, published a book titled "Colombian Heraldry" that collects with sober drawings all the coats of arms of the cities of the country, transcribing for each one of them, the royal dispositions or official documents by means of which they were granted. In the chapter referring to Medellín, he publishes the definitive coat of arms (that is, the current one), but does not transcribe the Royal Decree that granted it; instead, there is a transcription of the document from the Council of the Indies on the "Privilege of Arms".[14]

It was this document that motivated the historian Ortega to carry out an investigation to clarify historically and really which were the true arms that correspond to the city of Medellín, to finally publish the results in a future second edition of his work.[14] At the beginning of 1956 he contacted his friend Fabio Lozano y Lozano, resident in Madrid (Spain), to find out about the primitive coat of arms of the Villa de Medellín. Lozano went to the International Institute of Heraldry and Genealogy in Madrid, entity that proceeded to carry out the investigation, which was directed by the Chronicler of Arms Vicente de Cadenas y Vicent, who was also the director and founder of that Institute.[14]

During the course of the investigation, Vicente de Cadenas y Vicent kept Fabio Lozano informed of the details, who in turn informed Ortega of the progress of the investigations. By April of that same year the research was finished with notarial certification, a painting of the coat of arms and analogies, at a cost of 1,000 pesetas, or 25 dollars at the time.[14] After trying unsuccessfully to get entities such as the Colombian Academy of History or the Cultural Extension of the Government of Antioquia to buy the research documents, it was finally Martín del Corral from Medellín who acquired them, and after a year they arrived in the city, brought personally by Fabio Lozano. In summary, the documentation suggests that the true coat of arms of Medellín is the same as that of its Extremadura counterpart, since this research is based on the document issued by the Council of the Indies on February 9, 1678, on "Privilege of Arms".[14]

The text of the documentation refers in the following terms:

DON VICENTE DE CADENAS Y VICENT, DE CASTAÑAGA Y NOGUES, Chronicler of Arms of the Spanish State,

I CERTIFY: That being required to determine the Coat of Arms of the City of Medellín, in the old Kingdom of New Granada, today Colombia, it results the existence of a document granted on February 9, 1678 by which is attributed to the referred city of Medellín, in the New Kingdom of Granada, the same arms that its homonym and from whom it took the name, existing in Extremadura. By the aforementioned concession the arms referred to are described as follows: IN A FIELD OF AZURE, ON WAVES OF AZURE AND SILVER, A SILVER BRIDGE, DEFENDED BY TWO TOWERS OF THE SAME METAL, AT ITS ENDS, MAZONADO OF SABLE AND, IN THE CENTER OF THE BRIDGE, CRESTED AN IMAGE OF OUR LADY OF CANDLES.

Historically for our heraldic considerations, the Villa de Medellín, in Extremadura, current Province of Badajoz and jurisdiction of Don Benito located in the Diocese of Plasencia, had as Lord the Infante Don Sancho of Castile, who in 1373 rebuilt the old castle built in part by Don Peter I of Castile, by indispositions that had with the Infante Don Juan Alfonso to whom it belonged previously as own lordship.

Don John II of Castile created in 1452 the County of Medellín, to reward the remarkable services of Don Rodrigo Portocarrero and Monroy, to his Repostero Mayor, natural son of Don Pedro Portocarrero, V Lord of Moguer and who was already Lord of Medellín, incorporating the Castle and lands of the Lordship of the Count house.

Resulting by the mentioned document the concession of Arms of the Villa de Medellín in the new Kingdom of Granada, today Colombia, identical to those used by the Villa de Medellín in Extremadura and, being these the described ones previously in agreement with the documentation conserved in our National Historical Archive, in use of the attributions that to my charge are conferred, I certify them in the way that they are ascribed previously and that, painted they are united to this document.

And for the record where it is convenient I issue the present certification of Arms, signed, initialed, and sealed with mine, in Madrid on the seventh day of April, nineteen hundred and fifty-six.

(signed and sealed) VICENTE DE CADENAS Protocol 137, pages 81–82. Chronicler of Arms of the Spanish State.

LEGITIMATION: JOSÉ GONZÁLEZ PALOMINO, notary of the Illustrious College of Madrid, with residence in this capital, I legitimize the above signature and rubric of Mr. VICENTE DE CADENAS Y VICENT, DE CASTAÑAGA Y NOGUES, Chronicler of Arms of the Spanish State. – Madrid, April 9, 1956.

(Signed, signed and sealed): José González Palomino.

LEGALIZATION: We the undersigned, notaries of the Illustrious College of Madrid, with residence in this capital, legalize the sign, signature and rubric above of the notary of the same Mr. José González Palomino. – Madrid, April 9, 1956.

(Signed, signed and sealed): José L. Diez, Alejandro Santamaría y Rojas.

Once Martín del Corral had the documents in his possession and after analyzing them, he sent them to the Mayor of Medellín together with the official letter G 57–100 in which he expressed his concerns about what the investigation assures.[14] Consequently, the then Mayor José Gutiérrez Gómez, by means of official letter 271 of July 6, 1957, asked the Antioquian Academy of History to study the problem.[14]

For this reason the Academy held an extraordinary meeting and after several historical considerations and special confrontations,[note 5] issued, on July 10 of the same year, a decision that in synthesis emphasizes that the coat of arms should not be changed, considering it authentic in accordance with the Royal Decree and worthy of all compliance; They also emphasize that, according to volume 34 of the Enciclopedia Espasa, it is observed that the coat of arms of the Medellín Extremadura has aesthetic differences with the model sent, but fundamentally they note that the image of the Virgin is not the Purification —also called Virgin of Candelaria— as Cadenas assures, but the Annunciation. The ruling, signed by the president of the academy, was sent to the Mayor in the following terms:[14]

Ruling of the Antioquian Academy of History on the city's coat of arms.

Medellín, July 10, 1957.

With the care that the case requires I have been investigating everything concerning the coat of arms of Medellín to which your attentive letter of the current month refers, distinguished with the number 271 and to give a timely response I summoned the Academy of History, before which I presented the complete documentation of the case. Said corporation after a mature study recommended me to manifest to you what I would like to communicate to you:

The coat of arms that Medellín has been displaying since 1678, that is to say since barely three years after its foundation, has its origin in the Royal Decree given in Madrid in the same year of 1678, by the Majesty of King Charles II on March 31, which is kept in the Municipal Archives, in volume 26, year 1778, where it can be consulted.

In this document is drawn the Coat of Arms that was given to the newly founded Town; and it is opportune to suggest to you, that the exact copy is taken from there so that it is conserved in its integrity, because making the comparison with the Coat of Arms that is used officially in letterheads, it is observed that innovations have been introduced that do not appear in the original.

Regarding the drawing made by the Chronicler of Arms Don Vicente de Cadenas y Vicent that was sent to the City Hall to the worthy charge of you, we observe the following: In volume 34 of the Encyclopedia Espasa, page 18, you can consult the Coat of Arms of Medellín of Extremadura in Spain and you fall in the account that if the bridge is equal to the drawing, neither is the river nor the bases of the walls, and above all, what is fundamental, the Image of the Virgin is not that of Purification but that of the Annunciation.

That invocation was chosen by the crown in attention to the request of the Town Council, Justice and Regiment of this Town that requested it given the devotion for her of the neighbors. It is also observed that the attestations contained in the pieces that were sent to the City Hall refer to the person of Mr. Cadenas y Vicent, as Chronicler of Arms and to the officials that legalized the signatures; but the authentication of the coat of arms does not appear anywhere, which would be essential to advise the change of the current one, based on the secular use and in documents that are going to be two hundred and eighty years old.

In summary, the Academy has been unanimous in the concept that the use of the current coat of arms of the city of Medellín should not be changed, considering it authentic in accordance with the Royal Decree that has been mentioned and is worthy of all compliance.

But he takes the opportunity to suggest again to the City Hall to deign to copy faithfully the Coat of Arms just as it is in the aforementioned Royal Decree, so that it may be disclosed in official documents.

- (S.D.) Emilio Robledo,

- President of the Academy.

Meanwhile, the writer Hernán Escobar Escobar, who at that time was the director of the Historical Archive of Antioquia,[note 6] and thanks to his friendship with the historian Enrique Ortega Ricaurte, was informed of the details of the investigations, also had access to the research documents and also attended and participated in the extraordinary meeting held by the Antioquian Academy of History.[14] All this allowed him to conduct and publish in various print media a study in which he analyzes various aspects of the emblem of the city.

In these publications he concludes that the coat of arms sent by the Chronicler of Arms Vicente de Cadenas y Vicent did belong to the city of Medellín, and that it was given by the Council of the Indies on February 9, 1678, and that the Academy was right in the sense that the coat of arms known until now cannot and should not be changed, since in reality it is the one that belongs to the city since March 31, 1678. In addition, in its publications it clarifies some errors and contradictions contained in the Royal Decree.[14]

After the Academy's ruling, municipal entities began to use in all official media an almost exact copy of the drawing of the Royal Decree as suggested, and which was used until the 1980s, when a new stylistic version of the emblem began to be used. Currently, municipal entities use different stylistic versions.

Characteristics of the Royal Decree[edit]

The royal decree granting the coat of arms to the Villa de Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria de Medellín is transcribed in its entirety below:[1]

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Reproduction of the Royal Decree.[16] This document that arrived to the Villa de la Candelaria de Medellín was a copy of the Decree, since at that time the original document with the signature and seal of the King remained in Spain, and a copy was sent to the Indies. | ||

Don Charles (II) by the grace of God King of Castile, of Leon, of Aragon, of the two Sicilies, of Jerusalem, of Navarre, of Granada, of Toledo, of Valencia, of Murcia, of Jaen, of the Algarves, of Algeciras, of Gibraltar, of the Canary Islands, of the East and West Indies, Islands and mainland of the Ocean Sea, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, of Bravante and Milan, Count of Hapsburg, of Flanders, of Tyrol and Barcelona, Lord of Viscaya and Molina, etc.

Because the Town Council, Justice and Regiment of the Villa de Nuestra Señora de La Candelaria de Medellín that has been founded in the Sitio de Aná in the Province of Antioquia, has begged me in a letter of June twenty-fourth of last year of sixteen hundred and seventy-six to be of service to give it Arms for the luster of it as the others have them. And having been consulted about it by those of my Council of the Indies, I have had the good will to grant it the same Arms that the Villa de Medellín has in the Province of Extremadura in these Kingdoms and they are: A blue field shield and on it a very thick keep, round, all around crenellated and on it a coat of arms that has fifteen laces, seven blue and eight gold, and on its colonel that touches it and in the homage of the tower to each of the sides a turret, likewise crenellated and in the middle of them placed an image of Our Lady on a cloud, with her son in her arms with the invocation of the Annunciation in the form that follows: (here the graphic of the arms)

The said arms and motto I give and grant to the said Town so that it can bring them and put them and bring and put them on the banners, seals, shields and flags of it and in other parts where it wants and it is necessary, according to the form and manner that other cities of the Indies and of these my Kingdoms of Castile bring and put them, to whom they are given arms. And by this my letter I command the Dukes, Marquises, Prelates, Counts, Rich Men, Priors, Commanders, Mayors of the Castles and strong and plain Houses and those of my Council of the Indies and presidents and Judges of my Royal Audiences of them and the Governors, Captains and Justices and other my offices of the Indies, Islands and the mainland of the Ocean Sea and to the Councils and Magistrates of them and other judges and justices of the said Indies to keep and fulfill this my letter and what is contained in it in everything and for everything, according to and as it is contained in it, and that against its tenor and form they do not go, nor pass, nor consent nor pass now nor in any time whatsoever, which is my will.

- Given in Madrid on the thirty-first day of March one thousand six hundred and seventy-eight years.

- I The King.

- I Francisco de B. Madrigal. Secretary of the King Nro.

- Lord I made it written by his m.

The same royal decree refers to the documentation sent by the "Town Council, Justice and Regiment", dated June 24, 1676, where they request arms for the Villa de la Candelaria de Medellín. Further on, there is a description of the arms granted by King Charles II, and this document came with a drawing in two copies,[13] indicating what the arms for the new town should look like.

In order to understand the royal decree, it must be taken into account that it was written in 17th century Castilian, therefore its spelling and wording differ from contemporary Spanish. The following is an analysis of the blazon (description) and the drawing of the coat of arms, to understand the context of the period in which it was conceived.

The description of the arms begins with the following: (...) a blue field shield (...). The field in the strict sense designates in heraldry the background of the shield, it is the total surface of the same one and that is contained between the lines of its contour,[12] in this case the field is blue whose heraldic name is azure.

(...) and on it a very thick, round keep, all around crenellated (...). A keep is a large tower with military purposes, since in ancient times it served as defense of a square or a fortress.[13] Graphically, a keep is understood as a tower generally with a circular plan, a door and two windows, very used in Spanish heraldry and corresponding to the artificial figures.[12] The characteristics of a tower must be specified,[note 7] in this case the paragraph indicates that it must be wide, of circular plan and crowned with merlons.

(...) and on it a coat of arms that has fifteen laces, seven blue and eight gold, and on its colonel that touches it (...). Said coat of arms corresponds to the coat of arms of the House of Portocarrero, an ancient and extinct Spanish noble house, whose primitive arms are squares (checkered) of 15 pieces, 7 blue and 8 gold, the coat of arms is in homage to Pedro Portocarrero y Aragón, Count of Medellín.[12] The term "colonel" in heraldry simply refers to a crown,[17][13] an expression that today is in disuse. The reading of colonel in an ancient document is that of a crown and it does not matter the type, because at that time there was no classification system and crowns of all types were made, but especially open ones. The crown before the seventeenth and eighteenth century is paraheraldic, it has no function other than decorative. In this case, the term "colonel" refers to the fact that the coat of arms has a crown of ornamentation as a bell.

(...) and in the homage of the tower to each one of the sides a turret, likewise crenellated (...). The homage of the tower or homage tower, also called keep, was in ancient times the most outstanding tower of a fortress, it was the last redoubt of defense if the others succumbed, and it could be isolated from the rest of the fortification. In this case, the passage refers to a small crenellated tower on each side of the keep.

(...) and in the middle of them placed an image of Our Lady on a cloud, with her son in her arms with the invocation of the Annunciation (...) this part refers to the use of the hagiographic figure of the Virgin with the Child and the place arranged for its location is the place of honor of the shield, 15 the advocative error contained in this passage is explained later.

When analyzing the model that was sent in the document, it is possible to see who executed the drawing, since in the lower corners the words "Orozco Fecit" can be seen, which translates as "Orozco did it".[13]

In the drawing, from bottom to top, it is found first that all a terraced on which the tower rises is a surface that is not mentioned in the document. Then we can see the tower with a wide base, a uniform cylindrical shape, and a round arched doorway, two square windows, and is crowned with seven merlons.[12]

On the door of the tower there is a coat of arms (arms of the House of Portocarrero), which has some ornaments around it, as a bell it has an enhanced and open crown, on each side of the escutcheon there is a fleur-de-lis, and surrounding the coat of arms there are two lambrequins. These last two ornaments are not mentioned in the description of the royal decree.[12]

Above the keep, on each side, there is a small turret, also of uniform cylindrical shape, with a circular window and crowned with five merlons. It is worth noting that the number of merlons and the masonry, both of the keep and the turrets, are not recorded in the document.[12]

Between the turrets and on a cloud the hagiographic figure of the Virgin poses, who has a voluminous dress, in her right hand holds a candle (or flame) and in her left arm the Child, at her feet is a crescent moon and below it a cherub. On the head is a halo containing 19 points or rays and ends at the top in a cross, besides it emerges a glow that makes its way between two lateral clouds. Only the cloud in the center, the Virgin and the Child are indicated in the document, the other elements are part of the iconography of the Virgin of Candelaria, for this reason they are found in the drawing.[12]

In synthesis, the drawing is the complement of the description, since it defines details and shows other elements that were not enshrined in the royal decree; this was intended to clearly indicate how the coat of arms should be, thus avoiding misinterpretations, since, in heraldry, the pieces, furniture and other elements can have different aesthetic styles. For example, towers have various stylistic forms to be represented, and in this case a uniform cylindrical tower was desired.

Errors and contradictions in the Royal Decree[edit]

The analysis of the Royal Decree shows that it contains several errors and contradictions, which were clarified in the publications of the writer Hernán Escobar Escobar.[note 6] Thus, in one of its paragraphs we find the first error which is referred to in the following terms:

And having been consulted about it by those of my Council of the Indies, I have had the good will to grant it the same Arms that the Villa of Medellín has in the Province of Extremadura in these Kingdoms....

Here there is a contradiction, because the Council of the Indies had already given to the Villa de Medellín the same coat of arms of its Extremadura counterpart, but why did it not realize this detail when the king consulted them on the subject? Possibly, this council did mention something to him, and the king in reality what he wanted to say was that he granted "similar" arms to the Villa de Medellín de Extremadura, since the description of the escutcheon that he himself gives, does not agree with the coat of arms of the town of Extremadura, although they have characteristics in common.

Furthermore, if the Villa de Medellín already had the arms of its Extremadura counterpart, it makes no sense for the king to grant the same coat of arms that had already been given, unless what was sought was to give a new and definitive escutcheon. This would make more sense, since the new coat of arms would be an exclusive symbol of the town, thus complying with the Laws of Arms in the sense that there cannot be one coat of arms identical to another, since the purpose of these emblems is the individuality of lineages, cities, states, institutions, etc.[14]

Although it is possible that this error is due to the ignorance or little information that the King of Arms of the monarch Charles II had about the coat of arms of the Spanish town,[14] it could also have been generated by a bad communication with the Council of the Indies.

In another passage an advocative confusion is committed when attributing two incompatible religious representations, the passage refers in the following terms:

...in the midst of them placed an image of Our Lady on a cloud, with her son in her arms with the invocation of the Annunciation....

This is an error both in the text and in the drawing of the coat of arms that was included in the royal decree, since the Virgin of the Annunciation represents the announcement of the birth of Jesus and does not have to include the Child in her arms;[14] in addition, in the drawing of the shield was placed the Virgin of the Purification, that is also known as the Virgin of the Candelaria,[13] patron saint of the city, and that represents the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple and the Purification of the Blessed Virgin, 40 days after the birth of Christ, the Light of the world, that comes to illuminate all like the candle or the flames, from where the name of "Candelaria" is derived. It seems, then, that the Kings of Arms would have wanted to place the Virgin of the Purification, since the documentation sent by the town council mentioned this particular dedication.[12]

Another explanation that must be taken into account for the errors can be found in the context of the means of communication of the time, since the official writings were transcribed several times by different scribes, while the document with the original rubric and seal of the king remained in Spain, and in reality what was sent to the Indies was a copy of the original, perhaps deriving this process in the making of the errors.

Design[edit]

Heraldic emblems can be understood as the reproduction of graphic signs contained within an outline, generally in the form of a shield and whose description is known as the escutcheon, the very essence of the emblem itself, together with the various elements outside that outline in case it has them. Regarding the coat of arms of Medellín, its design corresponds to the escutcheon (and the model) indicated in the royal decree of March 31, 1678, which has maintained its composition almost unaltered for more than 300 years, with no variations other than aesthetic ones.

On the other hand, the shape of the coat of arms has its variations; for example, municipal entities usually represent the coat of arms with the outline corresponding to the so-called modern French style, a quadrilateral outline whose lower corners are rounded with a quarter circle (a half part), and in the center of the lower part it is equipped with a point formed by the union of two quarter circles of the same proportion. It is probably preferred for its rectangular shape, as it facilitates drawing, since the model of the royal decree is contained in a rectangle. Moreover, this outline has been used for a long time, as evidenced by a series of coats of arms of the city found in the Basílica de la Candelaria, the former cathedral and seat of the oldest parish in Medellín.[note 11]

Although its proportions are not legally established, the coat of arms used by the municipality has somewhat exaggerated measures, as it is longer than normal, the usual proportion is 8 parts high by 7 wide, however, according to some authors a proportion of 9 high by 7 wide is also allowed,[18][19] which is the one used in Italian heraldry,[20] being these the maximum measures used in the modern French style and, in this case, would be recommended for the coat of arms of the city.

Another possible contour, and the second most used, is the one that corresponds to the traditional Spanish heraldic style, a quadrilateral contour with a rounded base, with a proportion of 6 high by 5 wide,[note 10] which is preferred in the publications of historians to represent the coat of arms of the city,[note 12] probably because it is considered the most common among Hispanic escutcheons. Another form used in publications, but to a lesser extent, is the so-called English style, an outline similar to the modern French, to which two small triangular projections are added at the ends of the upper part.

Escutcheon[edit]

The escutcheon is the description of a coat of arms. Throughout history the coat of arms of Medellín has been described in different ways:

Description of the Royal Decree

A blue field shield and on it a very thick keep, round, all around crenellated and on it a coat of arms that has fifteen laces, seven blue and eight gold, and on its colonel that touches it and in the homage of the tower to each of the sides a turret, likewise crenellated and in the middle of them placed an image of Our Lady on a cloud, with her son in her arms with the dedication of the Annunciation in the form that follows

The royal decree —written in 17th century Castilian— gives a basic description of the escutcheon, which is complemented by the drawing that came with the document, and as mentioned above, it defines the forms and brings other elements that are not mentioned in the text, but even so, some aspects were left undefined.

Description of the Decree No. 151 of February 20, 2002[3]

... the coat of arms of the city is on a blue background, it has a tower with a wide and round base, and an ornamented surrounding ending in seven merlons. Above the door and in the middle of two small windows is a coat of arms, which has 15 boxes or squares, seven blue and eight gold, and ends in a heraldic crown. And in the superior part of the tower, to each one of the sides an adorned turret and in the middle of them on a cloud, an image of Our Lady of the Candles with her Child in arms.

Decree No. 151 of February 20, 2002, which defines the new administrative structure of the municipality and establishes other provisions, such as the one that refers to the arms of the city (exactly in Chapter IV – Of the regime of the Municipality. Article 12 – Medellín Coat of Arms) is only limited to that description and does not indicate or regulate the use of the emblem.[3]

Description from the web page of the City Hall of Medellín[21]

In a blue field is represented a gold keep and over the door a shield of 7 arms with 15 squares, 7 blue and 8 gold. In the upper part 2 keeps and in the middle of them the image of Our Lady of Candles, Patroness of the city.

The vague description of the City Hall, on which most of the descriptions on the web are based,[note 13] as well as several brochures and tourist guides, contains an error, because it says "...on the door a shield of 7 arms...", which is false, in reality it is not a shield of compound arms, it is a simple checkered shield of 15 pieces, 7 blue and 8 gold. In addition, they changed the words turrets that are diminutive of tower, for keeps that is augmentative of tower.

Description by José Antonio Benítez[22]

A Castle in Campo de Cielo, with two keeps, above the Gate a Heart with Yellow and Azure cartouches. In the middle of the two Towers, above the Castle, is portrayed Our Lady of Candles with her precious Child in her Arms, and a Torch in her Hand.

José Antonio Benítez was the official scribe of Antioquia from the end of the 18th century until the middle of the 19th century, and his description (on which some descriptions are based),[note 14] is the most erroneous of all, practically describing a new coat of arms, as he changes the tower for a castle and the checkered shield of 15 pieces, 7 blue and 8 gold, for a heart with yellow and blue cartouches.

Although it is understandable that the tower is perceived as a castle, since this building in the heraldry is represented as a wall (whose form can vary), with its merlons, a door and two windows; on this wall there are three towers, the middle one of greater height, all crenellated and each one with its window.[23] Although the tower agrees in almost everything to be a castle, it would only lack the tower in the middle, but in its place is the image of the Virgin.

These descriptions have two characteristics in common: none of them indicate the shape of the coat of arms, which has given rise to variations in the outline of the emblem among various styles, and none of them is truly structured in heraldic language. By analyzing both the text and the drawing of the royal decree, that is, the original granting document, we obtain a description that, although not official, is created using the precise terminology of heraldry.

Description in heraldic language

In a field of azure, a round keep of gold, mazoned and clarified of sable, charged with a shield checkered of 15 pieces, 7 blue and 8 gold (arms of the house of Portocarrero), stamped with an ancient crown of gold, and surmounted, between its two turrets, by the image of Our Lady of Candles carrying the Child, in her sinister arm, and a candle in her right hand, rayonant and bedded with clouds rising from each canton.

"Gold" keep[edit]

The keep was not originally made of "gold", since neither the Royal Decree nor Decree No. 151 of February 20, 2002,[3] which are the legal and valid documents, indicate its color. This de facto change is not clear when it was generated, but already some books published at the beginning of the 20th century contain, for some unknown reason, the word "gold" in the transcription they make of the Royal Decree that grants the arms,[note 15] remaining as follows: "...a keep of very thick gold...". The work called "Libro de actas del M. Y. Cavdo. y Rexmto. de la Villa de Medellín" published in 1932,[note 16] which gathers the transcriptions of the documents of the Town Council of the Villa de Medellín between 1675 and 1813, also for some unknown reason, in the transcription of the Royal Decree has the word "gold" added to it.[10] This work was a fundamental part of Hernán Escobar Escobar's research on the escutcheon of Medellín,[note 6] since, as he himself indicates in his study, it helped him to verify and take the transcriptions of the documents related to the coat of arms, among them the transcription of the royal decree that grants the arms.[14] Escobar, being the only person who has so far carried out a study on the emblem, is the main source of reference in most of the publications that touch on the escutcheon of the city, which, consequently, reproduce the error generated in the Book of Minutes of the Town Council.[note 15]

Diffusion of the arms of Medellín[edit]

In addition to the municipality, the arms of Medellín are present in the symbols of other institutions that, because of their close ties to the city, have adopted them, either in whole or in part. Likewise, due to its representative character, the coat of arms also appears in the most important decoration of the city and, in turn, has appeared in different commemorative elements of the most important dates of Medellín.

Archdiocese of Medellín[edit]

The Archdiocese of Medellín is one of the entities that uses the arms of the city. From its beginnings it did not have an official coat of arms despite its antiquity, for this reason Archbishop Tulio Botero Salazar, after taking possession of the archiepiscopal see in 1958, and seeing this problem, decided that to identify the archdiocese in its official documents, the same coat of arms that for 300 years has identified the city would be used, and, by decree of June 30 of the same year, adopted the coat of arms of Medellín as the official emblem,[13] adding the archiepiscopal cross as a stamp and the motto of the name of the archdiocese at the bottom.[1]

The decree refers in the following terms:[24]

Our Father Tulio Botero SalazarBy the Grace of God and the Will of the Apostolic SeeArchbishop of MedellínConsidering:A) that it is convenient to have an Official Coat of Arms of the Archdiocese;

B) that the historical Coat of Arms of the City of Medellín exists.

We decree:Article 1. That the OFFICIAL COAT OF ARCHDIOCESE OF MEDELLÍN be adopted as the COAT OF ARCHDIOCESE OF MEDELLÍN, that is: "blue field shield and on it a very thick keep, round, all around crenellated and on it a coat of arms that has fifteen laces, seven blue and eight gold, and on its colonel that touches it and in the homage of the tower to each of the sides a turret, likewise crenellated and in the middle of them placed an image of Our Lady on a cloud, with her son in her arms with the invocation of the Annunciation" (Royal Decree of March 31, 1678).

Article 2. Introduce the variant of the double archiepiscopal cross, placed in the upper part of the coat of arms.

Communicate and comply. Given in Medellín on June 30, 1958.

- Tulio Botero Salazar

- Archbishop of Medellín

- Bishop Octavio Betancur Arango

- Auxiliary

It is noteworthy that, apart from the stylistic differences, the coat of arms of the Archdiocese does not comply with two characteristics of the escutcheon of the city. The checkered shield of 15 pieces, 7 blue and 8 gold, was changed for a checkered heart and the Virgin, instead of resting on a cloud, rests directly on the tower. In addition, each one of the turrets ends in a dome, a detail that the arms of the city do not have.

Educational entities with the arms of Medellín[edit]

Another entity that uses the arms of the city is the University of Medellín, whose coat of arms was designed by Francisco López de Mesa, a member of the group of founders.[4] The coat of arms of the emblem has a pointed outline, quartered, and in its first quarter are located the arms of the Villa de la Candelaria de Medellín, which represent the link that the university has with the city, from which it takes its name.[4]

In addition, other educational institutions also use all or part of the arms of the city among their emblems, such as the "Colegio Mayor de Antioquia",[25] and the "Centro Formativo de Antioquia" —CEFA— which only have the tower,[26] and the "Institución Educativa Alcaldía de Medellín" has both the tower and the hagiographic figure of the Virgin and Child.[27] These last three educational institutions belong to the municipality.

Seal of the Free State of Antioquia[edit]

Another emblem that featured the arms of Medellín, at least partially, was the Seal of the Free State of Antioquia, which only used the keep. This seal emerged in the midst of the events of the Colombian Independence, when the then Province of Antioquia declared its independence from the Spanish Crown on July 29, 1811, with the name of Free and Independent State. In recognition of this, the President of Antioquia, José María Montoya Duque, approved by special decree the Gran Sello de Antioquia (Great Seal of Antioquia) on September 2, 1811, for use as the seal and insignia of the State, as well as its use on the uniforms of its representatives and those of the Royal Court of Finance.

Said seal consisted of a double oval, the innermost of them divided into five-quarters surrounded by the inscription Fe Publica Del Estado Lybre E Yndependyente De Antioquia, surrounded in turn by a palm branch and an olive branch. Of the first four-quarters, the first showed a tree with a raven, the second a tower, the third a lion and the fourth showed two linked hands and arms. These quarters represented the coats of arms of the cities of Santa Fe de Antioquia, Medellín, Rionegro and Marinilla, respectively, while the last quarter contained six branches gathered with a ribbon bearing the inscription R.Z.C.B.Y.C., initials of the towns of Remedios, Zaragoza, Cáceres, San Bartolomé, Yolombó and Cancán (today Amalfi), in their order.[28]

The document approving said seal refers in the following terms:[29]

In the city of Antioquia, capital of the Province, on the second day of September one thousand eight hundred and eleven, the Supreme Legislative Power having assembled in its Palace, and having proposed as the subject of its deliberations the seal to be used by the State, the insignia and uniforms of the individuals of the National Representation, and of the Tribunal of the Royal Treasury, it was agreed as follows:

That the seal of the State be immediately broken in oval form, divided into five quarters and with an inscription on the circumference reading: FE PVBLICA DEL ESTADO LYBRE E YNDEPENDYENTE DE ANTYOQUYA, which shall be bordered on one side with a palm, and on the other with an olive tree. The principal of the five quarters will be occupied by a raven perched on a leafy tree; the second, a tower; the third, a lion; the fourth, two hands and arms intertwined, and the fifth six palm branches gathered with a ribbon. And in the extremity the six initials R.Z.C.B.Y.C.B whose arms are allusive to the four illustrious City Councils; and those of the last quarter, to the six places not subject to capitular department.

Lucio de Villa, Juan Elías López, Manuel Antonio Martínez, Juan Nicolás de Hoyos, José Antonio Gómez, Silvestre Vélez, secretary.

Later and with the passage of time the Free State of Antioquia adopted other emblems, leaving the Great Seal of Antioquia in disuse.

Medellín City Hall Medal[edit]

The Medalla Alcaldía de Medellín is the highest distinction of the municipal administration, and was established by Decree 845 of August 10, 1992, when Luis Alfredo Ramos Botero was Mayor of Medellín. This decoration consists of a metal disk, on the obverse side of which there is a reproduction in relief of the arms of the city and, on the reverse side, the legend "Medalla Alcaldía de Medellín" (Medal of the City Hall of Medellín). In addition, the medal is attached to a ribbon with the colors of the municipal flag, which allows it to be hung around the neck for display. It is also accompanied by a lapel shield and a military lapel shield, both with the same design as the main medal.

The decoration comes only in gold category, and is conferred by "decree of honors" to individuals or institutions as a token of recognition and gratitude for outstanding achievements in any of the fields such as social, cultural, economic, ecological, educational, sports, recreational and welfare in the city and the country. In addition, the Mayor of Medellín has sole authority to decide on its granting and is the only one who can deliver it, without the possibility of delegation.

Stamp with the arms of Medellín[edit]

In 1975, as part of the celebrations of the 300th anniversary of the "legal" founding of Medellín, a stamp was issued with the reproduction of the arms of Medellín as the central figure, and the outline used on this occasion is that corresponding to the Spanish style. The stamp is part of the Heraldic Series programmed by the National Government of Colombia as a way of linking to the commemorative dates of the founding of the cities of the country; in this case, as a recognition to the inhabitants and the city of Medellín.

The stamp was issued on November 4 of the same year, with a format of 30 x 40 mm and a face value of 1 peso for domestic mail only. 1,500,000 units were issued; the special sheet consists of 50 stamps and, in addition, 5,000 first day envelopes were issued.[30] Around the escutcheon, at the bottom is the legend "1675-MEDELLÍN-1975" and at the top is the word "COLOMBIA" and just below it the numeral value "$ 1ºº".

Commemorative coins with the arms of Medellín[edit]

Also as part of the city's tercentenary celebrations, in 1975, two commemorative gold coins were minted, on which the arms of the city were depicted. The coat of arms used on these coins is possibly based on the drawing that was included in the royal decree, as the tower is slightly displaced to the right of the rectangle, as is the model of the document.

Both coins are of the same design, only the size and face value vary, they are made in gold law 0.900, are square in shape, and have the values of 1,000 and 2,000 Colombian pesos. The coin of the first value has a dimension of 17.5 x 17.5 mm and weighs 4.25 grams, and the second has 21 x 21 mm and weighs 8.5 grams.[31] On the obverse, the central figure is the "Coat of Arms of Medellín" flanked by olive branches; around the coat of arms, on the upper part is the legend "REPÚBLICA DE COLOMBIA" and on the lower part the years "1675 - 1975". On the reverse, the central figure is a bouquet of orchids, around it is the legend "TRICENTENARIO DE MEDELLÍN" at the top, and at the bottom is the value in letters and numbers, and "900/1000 ORO" indicating the purity of the metal.[31] A total of 8,000 pieces were minted, of which half were for 1,000 pesos and the rest for 2,000 pesos.[32] They are also the only two square-shaped Colombian coins.

These commemorative coins, although declared legal tender, and therefore, with liberatory power, never entered into circulation, since they were only created for collection purposes. Moreover, their face value is much lower than their acquisition value, which corresponded to the cost of the gold used in their manufacture, according to the market cost, increased by a premium of around 20%.[33]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Escutcheon based on both the text and the drawing of the royal decree of March 31, 1678, granting the coat of arms.

- ^ The indigenous reservation known as "El Poblado de San Lorenzo" was discarded because the laws of racial segregation prevented mestizos and mulattos from settling in the reservations, and also because of the precarious living conditions.

- ^ Pedro Portocarrero, Folch de Aragón y Córdoba, Count of Medellín, Marquis of Villa Real, Duke of Camiña, Major Reporter of the Royal House of Castile, Member of the King's Chamber and President of the Council of the Indies (titles he held at that time according to José Antonio Benítez, official scribe of Antioquia from the late 18th to the mid-19th century).

- ^ This version of the Medellín coat of arms is found in the following books:

- Under the direction of Juan Clímaco Vélez, Abel García Valencia, Juan Clímaco Vélez, Abel García Valencia, Juan Clímaco Vélez and Abel García Valencia. (1925). Medellín 1675–1925 (in Spanish). Medellín: Linotipos de "El Colombiano". OCLC 637046434.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - García, Julio César (1937). Historia de Colombia (in Spanish). Medellín: Imprenta Universidad. OCLC 21484683.

This publication has the shield in black and white.

- Under the direction of Juan Clímaco Vélez, Abel García Valencia, Juan Clímaco Vélez, Abel García Valencia, Juan Clímaco Vélez and Abel García Valencia. (1925). Medellín 1675–1925 (in Spanish). Medellín: Linotipos de "El Colombiano". OCLC 637046434.

- ^ The extraordinary meeting of the Antioquia Academy of History was chaired by Emilio Robledo, president of the Academy, and was attended by Luis mountain chain H., Pbro. Jesús Mejía Escobar, Luis Mesa Villa, Carlos Arturo Jaramillo, Abraham González, Enrique Echavarría, José Solís Moncada and as a special invitation of Robledo, the writer Hernán Escobar Escobar Escobar.

- ^ a b c Hernán Escobar Escobar

He was born in Medellín on November 9, 1925. He studied in the United States as a Technician in Documents and Archives Administration and in Europe specialized in his profession. He was for several years the Director of the Historical Archives of Antioquia and the Head of the Archives Section of the E.P.M.. He gave technical assistance to several archives, including the Historical Archive of Cali. He was a contributor to numerous national publications. He belonged to several Colombian and foreign academies, including the Franciscan Academy of History and the Ecclesiastical History Academy sponsored by the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana. A recognized expert in heraldry, he won several competitions for municipal emblems such as those of Itagüí and La Estrella. He has won several contests of historical nature and has received several decorations and titles. He is the author of the following works:

"El Histórico Retablo de Nuestra Señora de Chiquinquirá de los Llanos de Niquía", "Antioquia al Libertador Simón Bolívar", "La Virgen de la Estrella", "Algo de lo Nuestro", "Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria de Medellín", the first volume of the "index of the Colony of the Historical Archive", "Historical heraldic and analytical study of the heraldic symbols of the Municipality of Itagüí". - ^ The heraldry should indicate whether the towers are round, square or covered, crenellated with different merlons and the color of their doors and windows, lightened or mazoned.

- ^ Original drawing of the coat of arms of Medellín that came integrated in the royal decree, taken from the book titled "Libro de oro de Medellín: en el tricentenario de su erección en Villa, 1675 – 2 de noviembre – 1975" (1975)". According to the book, it is the original, but possibly this image has lost some color over the years".

- ^ Almost exact copy of the original drawing of the coat of arms of Medellín that was included in the royal decree, taken from the book "Medellín, su Origen, Progreso y Desarrollo" (1981) by Jorge Restrepo Uribe. ISBN 84-300-3286-X. Page 28

- ^ a b Messía de la Cerda y Pita, Luis F. (1990). Spanish heraldry: the heraldic design. Aldaba Ediciones, Madrid. ISBN 84-86629-36-5. "As a general rule, all treatises point out proportions of five equal parts of width by six equal parts of height for the Spanish coat of arms. These proportions are for anatomical reasons, since in the 12th century the average height of Spaniards was between 1.50 and 1.60 meters. The task of the shield is to protect the warrior or knight in combat; therefore, it should cover from the thigh to the height of the eyes and, horizontally, the chest and both shoulders; a shield of dimensions 50 x 60 cm meets the above requirements and a standard shield is obtained, suitable for most Spaniards of the twelfth, thirteenth and following centuries. From all that has been indicated, the proportion of 50 x 60 cm is obtained, that is, FIVE to SIX, and therefore the one adopted for the representations of the Spanish coat of arms. "

- ^ In the Basilica of Our Lady of Candelaria there are three coats of arms of Medellín located in the following places:

- At the top of the old baptistery and made in painted wood.

- On the Altar table and made of silver.

- On the pediment of the main façade.

- ^ Both the historian Germán Suárez Escudero in his book "Medellín, Estampas y Brochazos" of 1994; the historian and heraldist Enrique Ortega Ricaurte in his book "Heráldica Colombiana" of 1952, and the writer Hernán Escobar Escobar, in the chapter "Historia" of the book "Monografía de Medellín", have the coat of arms of Medellín in the Spanish form, although the latter also has in that chapter a version with the form that corresponds to the modern French style.

- ^ As of the date of this reference, these pages reproduce the description of the web page of the City Hall of Medellín:

- paisas.info Page about the department of Antioquia and Medellín.

- sospaisa.com Page about Medellín sponsored by the City Hall of Medellín.

- colombia.com Tourist page about Colombia.

- conexionciudad.com Page about Antioquia and Medellín sponsored by COMFENALCO.

- Page of the Academic Extension Network of the National University —REUNA—

- lea.org, The Encyclopedia of Antioquia.[permanent dead link]

- Hotel Park 10 one of the main hotels in Medellín.

- ^ As of the date of this reference, these portals have a description of the Medellín coat of arms based on the José Antonio Benítez:

- historiadeantioquia.info portal about Antioquia and Medellín

- Medellín.travel Page about Medellín sponsored by the City Hall of Medellín.

- miradaurbana.com portal about Antioquia and Medellín.

- desfiledeautosantiguos.com Official page of the Classic and Antique Car Parade held every year in Medellín. Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- eventoselhospital.com Portal of the events of the Hospital Universitario San Vicente.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Some books that reproduce all or part of the transcription of the Royal Decree that grants arms to Medellín and that contain the error of "keep of gold":

- Historia e historias de Medellín (1927) Author: Luis Latorre Mendoza. P. 112

- Medellín en 1932 (1932) Author: Luis F. Pérez, Enrique Restrepo Jaramillo. Page 10

- Estudio: Heráldica y Armorial Antioqueño (1959) Author: Alicia Mejía García. P. 115

- Historia del departamento de Antioquia (1968) Author: Francisco Duque Betancur. P. 306

- Medellín, su Origen, Progreso y Desarrollo (1981) Author: Jorge Restrepo Uribe. P. 29

- Trescientos sesenta y dos años de Medellín y crónicas de la ciudad: 1616-marzo 2-1978 (1979) Author: Humberto Bronx. P. 102

- Medellín: construcción de una ciudad (2005) Author: Beatriz Adelaida Jaramillo P. Page 32.

- ^ The work called "Libro de actas del M. Y. Cavdo. y Rexmto. de la Villa de Medellín", also known simply as "Libro de actas del Cabildo" (Book of minutes of the Town Council), is a compilation of the transcriptions of the documents of the Town Council of the Villa de Medellín between 1675 and 1813, the work is a much cited source especially in publications that have to do with the history of Medellín.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e "Nuestro Escudo" (in Spanish). Arquidiócesis de Medellín. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "Escudos/Blasones de Medellín, España" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Medellín. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Alcaldía de Medellín (February 20, 2002). "DECRETO No. 151" (PDF) (in Spanish). Capítulo IV – Del régimen del Municipio. Artículo 12 – Escudo De Medellín. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Símbolos de la Universidad" (in Spanish). Universidad de Medellín. Retrieved March 9, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d Restrepo Uribe, Jorge (1981). "Capítulo I: Historia". Medellín, su Origen, Progreso y Desarrollo (in Spanish). Medellín: Servigráficas. pp. 25–30. ISBN 84-300-3286-X.

- ^ Sociedad de Mejoras Públicas de Medellín (1975). Medellín ciudad tricentenaria : 1675–1975, pasado – presente – futuro (in Spanish) (Editorial Bedout ed.). Medellín. OCLC 2375599.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Rodríguez Jiménez, Pablo (February 2009). "Medellín: La ciudad y su gente". Revista Credencial Historia (in Spanish) (230). ISSN 0121-3296.

Article on the history of Medellín, it also contains the copy based on the original drawing of the royal charter, the version that predominates in the publications.

- ^ Bernal Nicholls, Alberto (1976). "Escudo de Armas de la Villa de Medellín". Apuntaciones sobre los orígenes de Medellín (in Spanish). Medellín: Editorial Universidad de Antioquia. pp. 76–78. OCLC 2648243.

- ^ Concejo de Medellín. "Historia" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 5, 2015. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

Text taken from the book: "330 years of History of Medellín. Past, present and future" from the texts of the academicians: José María Bravo Betancur, Evelio Ramírez Martínez and Socorro Inés Restrepo Restrepo.

- ^ a b c d e Monsalve, Manuel (Annotations) (1932). Libro de actas del M. Y. Cavdo. y Rexmto. de la Villa de Medellín (in Spanish). Vol. I. Medellín: Imprenta Oficial. pp. 97, 108–110, 115–116. OCLC 3054619.

This work gathers the transcriptions of the documents of the Town Council of the Villa de Medellín between 1675 and 1813.

- ^ Ortega Ricaurte, Enrique (1952). Heráldica Colombiana (in Spanish). Bogotá: Minerva. pp. 165–170. OCLC 2183896.

In turn taken from "Boletín de Historia y Antigüedades," number 105, January 1915, Year IX, pages 545, 554, 555, 558 and 559, Bogotá".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Escobar Escobar, Hernán (February 20, 1956). "El Escudo de Armas de Medellín". Periódico el Colombiano (in Spanish): 3, 18.

- ^ a b c d e f g Piedrahita Echeverri, Monseñor Javier (2006). "Escudo de Armas". Monografía Histórica de la Parroquia de la Candelaria (in Spanish). Medellín: Grafoprint. pp. 87–92.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Escobar Escobar, Hernán (1959). "Capítulo I: Historia". Monografía de Medellín (in Spanish). Medellín: Ediciones Hemisferio. pp. 25–42. OCLC 45242097.

- ^ Reproduction of part of the research documents of Vicente de Cadenas y Vicent, taken from the book Crónica Municipal (1967), "Capitulo: Armas para la Villa 1678" by Hernán Escobar Escobar, p. 180.

- ^ Reproduction of the Royal Decree taken from the book titled: Crónica municipal (1967) (in Spanish). Concejo de Medellín. OCLC 316960631.

- ^ "Glosario heráldico – Coronel" (in Spanish). Libro de armoria. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

Page dedicated to heraldry in general and of consultation for those interested in this discipline.

- ^ Caratti di Valfrei, Lorenzo (2003). Araldica (in Italian). Milán: Arnoldo Mondadori. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-88-04-41105-5.

- ^ Giacomo, Bascapè; Del Piazzo, Marcello (2009). Insegni e simboli. Araldica pubblica e privata medievale e moderna (in Italian). Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali, Roma. p. 713. ISBN 978-88-7125-159-2.

- ^ "Caratteristiche tecniche degli emblemi araldici" (in Italian). Governo italiano. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

The modern French coat of arms was adopted as the official outline of Italian civic and military heraldry and, in this case, its official dimensions are 9 × 7.

- ^ "Nuestros Simbolos". City Hall of Medellín-Antioquia. Consulted on March 9, 2010. "As of the date of this reference, the City Hall has this description. The address is dynamic and changes from time to time. "

- ^ Benítez, José Antonio (1988). Carnero y miscelánea de varias noticias, antiguas y modernas, de esta Villa de Medellín (in Spanish). Transcription, foreword and notes by Roberto Luis Jaramillo. Medellín: Edinalco. OCLC 463571671.

- ^ "Diseño heráldico – Figuras artificiales – Castillo" (in Spanish). heraldaria. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

Page dedicated to heraldry.

- ^ Arquidiócesis de Medellín (1978). "Decreto sobre el escudo de la Arquidiócesis". Anuario 1977 de la Arquidiócesis de Medellín (in Spanish). Medellín: Com-pas Ediciones. p. 9.

- ^ "Institución Universitaria Colegio Mayor de Antioquia" (in Spanish). Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ Centro Formativo de Antioquia. "Escudo" (in Spanish). Retrieved March 9, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Institución Educativa Alcaldía de Medellín. "Símbolos" (in Spanish). Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ Llano Isaza, Rodrigo. "Antioquia" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on August 15, 2009. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ Baena, José Gabriel; Vives Mejía, Gustavo. "Santa Fe de Antioquia: Breve Monografía" (PDF) (in Spanish). pp. 40–41. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 7, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ Salazar Trujillo, Oscar (December 26, 1975). "Emisiones portales en 1975". Periódico el Tiempo (in Spanish): 7–B. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Restrepo, Jorge Emilio (2007). Monedas de Colombia: 1619 – 2006 (in Spanish).

- ^ Cuhaj, George S.; Michael, Thomas (2009). 2010 Standard Catalog of World Coins – 1901–2000. Krause Publications. ISBN 978-0-89689-814-1.

- ^ Néstor Ricardo, Chacón (2005). Derecho Monetario (in Spanish). Editorial Universidad del Rosario.

Bibliography[edit]

- Escobar Escobar, Hernán (1959). "Capítulo I: Historia". Monografía de Medellín (in Spanish). Medellín: Ediciones Hemisferio. OCLC 45242097.

- Escobar Escobar, Hernán (1967). "Capítulo: Armas para la Villa 1678". Crónica municipal (in Spanish). Concejo de Medellín. OCLC 316960631.

- Restrepo Uribe, Jorge (1981). Medellín, su Origen, Progreso y Desarrollo (in Spanish). Medellín: Servigraficas. ISBN 84-300-3286-X.

- Ortega Ricaurte, Enrique (1952). Heráldica Colombiana. Bogotá: Minerva. OCLC 2183896.

In turn taken from "Boletín de Historia y Antigüedades," number 105, January 1915, Year IX, pages 545, 554, 555, 558 and 559, Bogotá".

External links[edit]

- Page of the City Hall of Medellín about its symbols (in Spanish) (The address is dynamic and changes from time to time).

- Old page of the City Hall of Medellín about its symbols. (in Spanish)