Dear Lord and Father of Mankind

| Dear Lord and Father of Mankind | |

|---|---|

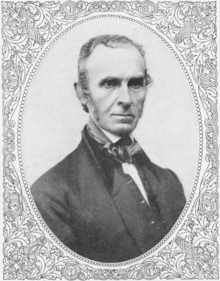

| by John Greenleaf Whittier | |

John Greenleaf Whittier | |

| Genre | Hymn |

| Written | 1872 |

| Meter | 8.6.8.8.6 |

| Melody | "Rest" by Frederick Charles Maker, "Repton" by Hubert Parry |

"Dear Lord and Father of Mankind" is a hymn with words taken from a longer poem, "The Brewing of Soma" by American Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier. The adaptation was made by Garrett Horder in his 1884 Congregational Hymns.[1]

In the many countries the hymn is most usually sung to the tune "Repton" by Hubert Parry; however, in the US, the prevalent tune is "Rest" by Frederick Charles Maker.

Text[edit]

The text set appears below. Some hymnal editors omit the fourth stanza or resequence the stanza so that the fifth stanza as printed here comes last.

If sung to Parry's tune, "Repton", the last line of each stanza is repeated.

It is often customary, when singing the final stanza as printed here, to gradually sing louder from "Let sense be dumb...", reaching a crescendo on "...the earthquake, wind and fire", before then singing the last line "O still, small voice of calm" much more softly.

Dear Lord and Father of mankind,

Forgive our foolish ways!

Reclothe us in our rightful mind,

In purer lives Thy service find,

In deeper reverence, praise.

In simple trust like theirs who heard

Beside the Syrian sea

The gracious calling of the Lord,

Let us, like them, without a word

Rise up and follow Thee.

O Sabbath rest by Galilee!

O calm of hills above,

Where Jesus knelt to share with Thee

The silence of eternity

Interpreted by love!

With that deep hush subduing all

Our words and works that drown

The tender whisper of Thy call,

As noiseless let Thy blessing fall

As fell Thy manna down.

Drop Thy still dews of quietness,

Till all our strivings cease;

Take from our souls the strain and stress,

And let our ordered lives confess

The beauty of Thy peace.

Breathe through the heats of our desire

Thy coolness and Thy balm;

Let sense be dumb, let flesh retire;

Speak through the earthquake, wind, and fire,

O still, small voice of calm.

The Brewing of Soma[edit]

The text of the hymn is taken from a longer poem, "The Brewing of Soma". The poem was first published in the April 1872 issue of The Atlantic Monthly.[2] Soma was a sacred ritual drink in Vedic religion, going back to Proto-Indo-Iranian times (ca. 2000 BC), possibly with hallucinogenic properties.

The storyline is of Vedic priests brewing and drinking Soma in an attempt to experience divinity. It describes the whole population getting drunk on Soma. It compares this to some Christians' use of "music, incense, vigils drear, and trance, to bring the skies more near, or lift men up to heaven!" But all in vain – it is mere intoxication.

Whittier ends by describing the true method for contact with the divine, as practised by Quakers: sober lives dedicated to doing God's will, seeking silence and selflessness in order to hear the "still, small voice", described in I Kings 19:11-13 as the authentic voice of God, rather than earthquake, wind or fire.

The poem opens with a quote from the Rigveda, attributed to Vasishtha:

These libations mixed with milk have been prepared for Indra:

offer Soma to the drinker of Soma. (Rv. vii. 32, trans. Max Müller).[3]

Associated tunes[edit]

Hubert Parry originally wrote the music for what became Repton in 1888 for the contralto aria 'Long since in Egypt's plenteous land' in his oratorio Judith. In 1924 George Gilbert Stocks, director of music at Repton School, set it to 'Dear Lord and Father of mankind' in a supplement of tunes for use in the school chapel. Despite the need to repeat the last line of words, Repton provides an inspired matching of lyrics and tune. By this time, Rest, by Frederick Maker (matching the metrical pattern without repetition), was already well established with the lyrics in the United States.

Tunes it can be sung to are

- Repton by Hubert Parry

- Rest by Frederick Charles Maker

- Hammersmith by William Henry Gladstone

- Elegy for Dunkirk by Dario Marianelli

Serenity (song by Charles Ives)[edit]

The American composer Charles Ives took stanzas 14 and 16 of The Brewing of Soma ("O Sabbath rest.../Drop Thy still dews...") and set them to music as the song "Serenity"; however, Ives quite likely extracted his two stanzas from the hymn rather than from the original poem. Published in his collection: "114 songs", in 1919, the first documented performance of the Ives version was by mezzo-soprano Mary Bell, accompanied by pianist Julius Hijman.[4]

Uses[edit]

- In 2005 the hymn was voted second in BBC One show Songs of Praise poll to find the United Kingdom's favourite hymn.[5]

- It was used in the Broadway production of the musical Jekyll & Hyde, at the wedding scene.

- A Repton version can be heard being sung by the Bede College Choir in the 2007 film Atonement during the Dunkirk evacuation.[6]

- The pipes and drums of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards covered the hymn for their 2007 album, Spirit of the Glen: Journey.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Ian C. Bradley, Abide with me: the world of Victorian hymns (1997), p. 171; Google Books.

- ^ Osbeck, Kenneth W. 101 More Hymn Stories: The Inspiring True Stories Behind 101 Favorite Hymns. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications, 1985: 15. ISBN 0-8254-3420-3

- ^ Müller, Max (1859). A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature. London: Williams and Norgate. pp. 543–4. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ James B. Sinclair (2012) [1999]. A Descriptive Catalogue of The Music of Charles Ives. Yale University Press. hdl:10079/fa/music.mss.0014.1.

- ^ BBC Songs of Praise poll, released 27 October 2005 (Retrieved 18 May 2009).

- ^ Internet Movie Database

External links[edit]

Works related to Dear Lord and Father of Mankind at Wikisource

Works related to Dear Lord and Father of Mankind at Wikisource