Education of Generation Z

| Part of a series on |

| Social generations of the Western world |

|---|

|

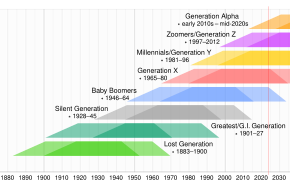

Generation Z (or Gen Z for short), colloquially also known as zoomers,[1][2] is the demographic cohort succeeding Millennials and preceding Generation Alpha.[3] Researchers and popular media use the mid-to-late 1990s as starting birth years and the early 2010s as ending birth years.[4] This article focuses specifically on the education of Generation Z.

Across the globe, Gen Z has generally high enrollment in primary schools in both developed and developing countries.[5]

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has supported research on educational spending and achievement in its 36 member states, and found that while spending increased in the early 2000s, academic performance has largely stagnated. Students from China and Singapore, both outside of the OECD, continued to outperform their peers. The OECD attributes socioeconomic background as a key factor in academic success, however, some countries demonstrate a weak link between background and performance, meaning these countries have the most equitable education systems.[6]

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the education of around one and a half billion students, as schools in 165 countries closed their doors and 60 million teachers were sent home, according to UNESCO.[7] Schools were partially or fully closed for nearly 80% of instruction time during the first year of the pandemic.[8] Some countries expanded access to the internet in remote areas or broadcast more educational materials on national television.[7] This wasn't an option in all contexts as internet access varied significantly and about two-thirds of people under the age of 25 around the world didn't have access to the internet at home.[8]

In the early 2000s, the number of students from emerging economies going abroad for higher education rose significantly. This was a golden age of growth for many Western universities admitting international students.[9] However, COVID-19 ended this golden age.[9]

This article expands on the education of Gen Z, including global trends and additional information for Asia, Europe, North America, and Oceania.

Global trends[edit]

Enrollment in primary schools in developing countries has been rising steadily since the mid-20th century. By the 1990s and 2000s, primary-school enrollment rates in these countries approached 100%, sitting just below those of the developed world.[5] According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), countries spent an average of US$10,759 educating their children from primary school to university in 2014.[10]

Over 600,000 students between the ages of eight and nine from 49 countries and territories took part in the 2015 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). The highest-scoring students in mathematics hailed from Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. In particular, the gap between the lowest scoring East Asian country (Japan, at 593) was 23 points higher than the next nation (Northern Ireland, at 570), which was unchanged from 2011. In science, the top scorers were from Singapore, South Korea, Japan, Russia, and Hong Kong.[11]

The OECD-sponsored Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) is administered every three years to fifteen-year-old schoolchildren around the world on reading comprehension, mathematics, and science. Students from 71 nations and territories took the PISA tests in 2015. Students with the highest average scores in mathematics came from Singapore, Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, and Japan; in science from Singapore, Japan, Estonia, Taiwan, and Finland; and in reading from Singapore, Hong Kong, Canada, Finland, and Ireland.[12]

In 2019, the OECD surveyed educational standards and achievement of its 36 member states and found that while education spending has gone up by an average of 15% over the previous decade, the academic performance of 15-year-old students in reading, mathematics, and science on the PISA has largely stagnated. Students from China and Singapore, both outside of the OECD, continued to outclass their global peers. Among all the countries that sent their students to take the PISA, only Albania, Colombia, Macao, Moldova, Peru, Portugal, and Qatar saw any improvements since joining. Of these, only Portugal is an OECD country. Meanwhile, Australia, Finland, Iceland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Slovakia, and South Korea all saw a decline in overall performance since joining. Funding, while important, is not necessarily the most important thing, as the case of Estonia demonstrates. Estonia spent 30% below the OECD average yet still achieved top marks.[6]

The socioeconomic background is a key factor in academic success in the OECD, with students coming from families in the top 10% of the income distribution being three years ahead in reading skills compared to those from the bottom 10%. However, the link between background and performance was weakest in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Japan, Norway, South Korea, and the United Kingdom, meaning these countries have the most equitable education systems.[6] A proposed method of assessing the equality of educational opportunities in a given society is to measure the heritability of academic ability as empirical evidence does support the hypothesis that the heritability of test results is higher in a country with a national curriculum compared to one with a decentralized system; having a national curriculum aimed at equality reduces environmental influences.[13]

Different nations and territories approach the question of how to nurture gifted students differently. During the 2000s and 2010s, whereas the Middle East and East Asia (especially China, Hong Kong, and South Korea) and Singapore actively sought them out and steered them towards top programs, Europe and the United States had in mind the goal of inclusion and chose to focus on helping struggling students. In 2010, for example, China unveiled a decade-long National Talent Development Plan to identify able students and guide them into STEM fields and careers in high demand; that same year, England dismantled its National Academy for Gifted and Talented Youth and redirected the funds to help low-scoring students get admitted to elite universities. Developmental cognitive psychologist David Geary observed that Western educators remained "resistant" to the possibility that even the most talented of schoolchildren needed encouragement and support and tended to concentrate on low performers. In addition, even though it is commonly believed that past a certain IQ benchmark (typically 120), practice becomes much more important than cognitive abilities in mastering new knowledge, recently published research papers based on longitudinal studies, such as the Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth (SMPY) and the Duke University Talent Identification Program, suggest otherwise.[14]

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted education of around one and a half billion students, as schools in 165 countries closed their doors and 60 million teachers were sent home, according to UNESCO.[7] Schools were partially or fully closed for nearly 80% of instruction time during the first year of the pandemic.[8] A number of countries tackled the problem by expanding access to the Internet in remote areas or broadcasting more educational materials on national television.[7] This wasn't an option in all contexts as internet access varied significantly depending on levels of economic development and about two thirds of young people under the age of 25 around the world didn't have access to the internet at home.[8]

Since the early 2000s, the number of students from emerging economies going abroad for higher education has risen markedly. During the 2010s, while the number electing to study in the United Kingdom and the United States largely evened out, more and more opted for Australia and Canada. This was a golden age of growth for many Western universities admitting international students.[9] In the late 2010s, around five million students trotted the globe each year for higher education, with the developed world being the most popular destinations and China the biggest source of international students.[9] Chinese government statistics show that 660,000 students studied abroad in 2018, more than thrice the number a decade prior. In 2019, the United States was the most popular destination for Chinese university students, with 30% of the international student body coming from mainland China, followed by Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Japan.[15] But as relations between the West and China soured and because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Western universities saw their revenue from foreign students plummet and will have to reconfigure themselves in order to survive. Government assistance might not be available due to the strained ties between universities and many politicians, who are skeptical of the value of higher education because even though admissions have boomed, productivity growth has slowed.[16] Moreover, political battles in the West are increasingly fought between those who have university degrees and those who do not. In any case, universities that are highly dependent on revenue for foreign students face the possibility of bankruptcy. COVID-19 has ended the golden age of universities.[9]

For information on public support for higher education (for domestic students) in various countries in 2019, see the chart below.

In Asia[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2022) |

In South Korea, teaching is a prestigious and rewarding position and the education system is highly centralized and focused on testing. Similarly, in Singapore, becoming a teacher is by no means an easy task and the nation's education system is also centrally managed.[10]

In Europe[edit]

In Finland, during the 2010s, it was extremely difficult to become a schoolteacher, as admissions rates for a teacher's training program were even lower than for programs in law or medicine.[10] According to the 2015 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), French students scored last in mathematics and next-to-last in science when compared to other member states of the European Union. French fourth graders (students aged eight to nine) scored an average of 488 points in mathematics and 487 in science, compared to the E.U. average of 527 and 525, respectively. Internationally, France ranked in 35th place out of the 49 participant countries and territories.[11] French mediocrity in mathematics at the level of grade school notwithstanding, the situation in higher education and research was a revelation, as can be seen in the number of Fields Medalists the nation has produced, which is more than any other country except the United States.[17][18]

In early 2020, the Paris-Saclay University opened. It merged some 20 tertiary and research institutions (including the elite grandes écoles and specialized research institutes), employs 9,000 teaching and research faculty members and serves 48,000 students. It is dedicated to science and is intended to be what President Emmanuel Macron called the "MIT à la française." Although the French were previously indifferent towards international rankings of universities, Paris-Saclay is, as of 2020, one of the best in the world, especially in mathematics.[18]

In France, while year-long mandatory military service for men was abolished in 1996 by President Jacques Chirac, who wanted to build a professional all-volunteer military,[19] all citizens between 17 and 25 years of age must still participate in the Defense and Citizenship Day (JAPD), when they are introduced to the French Armed Forces, and take language tests.[19] In 2019, President Macron introduced something similar to mandatory military service, but for teenagers, as promised during his presidential campaign. Known as the Service National Universel or SNU, it is a compulsory civic service. While students will not have to shave their heads or handle military equipment, they will have to sleep in tents, get up early (at 6:30 am), participate in various physical activities, raise the tricolor, and sing the national anthem. They will have to wear a uniform, though it is more akin to the outfit of security guards rather than military personnel. This program takes a total of four weeks. In the first two, youths learn how to provide first aid, how to navigate with a map, how to recognize fake news, emergency responses for various scenarios, and self-defense. In addition, they get health checks and get tested on their mastery of the French language, and they participate in debates on a variety of social issues, including environmentalism, state secularism, and gender equality. In the second fortnight, they volunteer with a charity for local government. The aim of this program is to promote national cohesion and patriotism, at a time of deep division on religious and political grounds, to get people out of their neighborhoods and regions, and mix people of different socioeconomic classes, something mandatory military service used to do. Supporters thought that teenagers rarely raise the national flag, spend too much time on their phones, and felt nostalgic for the era of compulsory military service, considered a rite of passage for young men and a tool of character-building. Critics argued that this program is inadequate, and would cost too much.[20] The SNU is projected to affect some 800,000 French citizens each year when it becomes mandatory for all aged 16 to 21 by 2026, at a cost of some €1.6 billion.[20] Another major concern is that it will overburden the French military, already stretched thin by counter-terrorism campaigns at home and abroad.[19] A 2015 IFOP poll revealed that 80% of the French people supported some kind of mandatory service, military, or civilian. At the same time, returning to conscription was also popular; supporters included 90% of the UMP party, 89% of the National Front (now the National Rally), 71% of the Socialist Party, and 67% of people aged 18 to 24. This poll was conducted after the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attacks.[21]

In the early 2010s, British schoolboys found themselves falling behind girls in reading comprehension. In 2011, only 80% of boys reached the expected reading level at age 11 compared to 88% of girls; the gap widened to 12 points at age 14. Previous research suggests this is due to the general tendency of boys not receiving a lot of encouragement in voluntary reading.[22] Teachers noticed that secondary schoolboys struggled to carry on reading. 25% said interest waned within the first few pages, 22% the first 50 pages, another 25% the first hundred. Almost a third reported that boys lost interest on the cover if the book had more than 200 pages. English-language literary classics most unpopular among boys included the novels of Jane Austen, the plays of William Shakespeare (especially Macbeth, The Tempest, and A Midsummer Night's Dream), and John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men.[23]

69% of British primary school teachers and 60% of secondary school teachers reported in 2018 they saw a growing frequency of substandard vocabulary levels in their students of all ages, leading to not just low self-esteem and various other behavioral and social problems, but also to greater difficulty in courses such as English and history and in important exams such as the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE), a set of school-leaving exams required for 16-year-olds. 49% of Year 1 students and 43% of children in Year 7 (ages 11 to 12) lacked the vocabulary to excel in school. Many believed that the decline in reading for pleasure among students, especially older teenagers, to be the cause of this trend. Psychologist Kate Nation warned, "Regardless of the causes, low levels of vocabulary set limits on literacy, understanding, learning the curriculum and can create a downward spiral of poor language which begins to affect all aspects of life."[24][25]

In 2017, almost half of Britons have received higher education by the age of 30. This is despite the fact that £9,000 worth of student fees were introduced in 2012. U.K. universities first introduced fees in autumn 1998 to address financial troubles and the fact that universities elsewhere charged tuition. Prime Minister Tony Blair introduced the goal of having half of young Britons earning a university degree in 1999, though he missed the 2010 deadline.[26] Blair did not take into account the historical reality that an oversupply of young people with high levels of education precipitated periods of political instability and unrest in various societies, from early modern Western Europe and late Tokugawa Japan to the Soviet Union, modern Iran, and the United States. Quantitative historian Peter Turchin termed this elite overproduction.[27][28] Turchin estimated that 30% of British university graduates were overqualified given the requirements of their jobs[29] while the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) reckoned that one out of five graduates would have been better off had they not gone to university.[16] The IFS also warned that 13 British universities risked bankruptcy as admissions fall precipitously due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Normally, admissions rise during an economic recession as people seek to enhance their competitiveness in the workforce, but this did not happen with the one induced by the pandemic due to requirements of social distancing and the availability of online classes.[16] Prime Minister Boris Johnson has made the case for better vocational training. "We need to recognize that a significant and growing minority of young people leave university and work in a non-graduate job," he said.[29]

Nevertheless, demand for higher education in the United Kingdom remains strong, driven by the need for high-skilled workers from both the public and private sectors. There was, however, a widening gender gap. As of 2017, women were more likely to attend or have attended university than men, 55% to 43%, a 12% gap.[26]

In North America[edit]

2018 PISA test results showed that in reading comprehension, Canadian high-school students ranked above the OECD average, but below China and Singapore. Students from Alberta scored above the national average, from British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nova Scotia about average, and Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island below average. Nationally, 14% of Canadian students scored below Level 2 (407 points or higher), but with a significant gender gap. While 90% of girls were at Level 2 or higher, only 82% of boys did the same, in spite of the initiatives aimed at encouraging boys to read more. Overall, the Canadian PISA reading average has declined since 2000, albeit with a significant bump in 2015. In mathematics, Canada was behind China, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Estonia, and Finland that year, when 600,000 students from 79 countries took the PISA tests. There was no improvement in the mathematical skills of Canadian students since 2012 as assessed by PISA, with one in six students scoring below the benchmark.[30][31]

During the 2010s, investigative journalists and authorities have unveiled numerous instances of academic dishonesty in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, ranging from contract cheating (buying an essay, hiring someone to complete an assignment, or to take an exam) to bribing admissions officers. In some instances, advertisements for contract cheating were found right next to university campuses. The actual prevalence of plagiarism remains unknown, and early research might have underestimated the true extent of this behavior.[32]

According to the World Economic Forum, over one in five members of Generation Z are interested in attending a trade or technical school instead of a college or university.[33] In the United States today, high school students are generally encouraged to attend college or university after graduation while the options of technical school and vocational training are often neglected.[34] According to the 2018 CNBC All-American Economic Survey, only 40% of Americans believed that the financial cost of a four-year university degree is justified, down from 44% five years before. Moreover, only 50% believed a four-year program is the best kind of training, down from 60%, and the number of people who saw value in a two-year program jumped from 18% to 26%. These findings are consistent with other reports.[35]

Because jobs (that matched what one studied) were so difficult to find in the few years following the Great Recession, the value of getting a liberal arts degree and studying the humanities at university came into question, their ability to develop a well-rounded and broad-minded individual notwithstanding.[36] While the number of students majoring in the humanities has fallen significantly, those in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, or STEM, have risen sharply.[37] About a quarter of American university students failed to graduate within six years in the late 2010s and those who did face diminishing wage premiums.[16]

According to the 2018 National Assessment of Educational Progress, 73% of American eighth and twelfth graders had deficient writing skills.[38] There have been numerous reports in the 2010s on how U.S. students were falling behind their international counterparts in the STEM subjects, especially those from (East) Asia. This is a source of concern for some because academically gifted students in STEM can have an inordinately positive impact on the national economy. In addition, while American students are less focused on STEM, students from China and India are not only outperforming them but are also coming to the United States in large numbers for higher education.[39]

Data from the Institute of International Education (IIE) showed that compared to the 2013–14 academic year, the number of foreign students enrolled in American colleges and universities grew in 2015–6 to about 300,000 students, before falling slightly in subsequent years. Compared to the 2017–18 academic year, 2018–19 saw for the first time in a decade a drop of 1% in the number of foreign students enrolled. This became a concern for institutions that relied on international enrollment for revenue, as they typically charged foreign students more for tuition than their domestic counterparts. However, the number of foreign graduates who stayed for work or further training had increased. In 2019, there were 220,000 who were authorized to stay for temporary work, a 10% rise compared to fall 2017. The top sources of students studying abroad in the United States were China, South Korea, India, and Saudi Arabia (in that order). The number of Chinese students studying in the United States had fallen since 2019 due to a confluence of factors, which included greater difficulty in obtaining a U.S. visa amid a deterioration in the bilateral relationship, increased competition from the Canadian and Australian higher education systems, and growing anti-Chinese sentiments due to concerns over intellectual property theft. However, students coming from elsewhere in Asia (though not South Korea and Japan), Latin America, and Africa had gone up. In particular, the number of Nigerian students climbed 6% while those from Brazil and Bangladesh rose 10%. The most popular majors had shifted, with business (an academic subject extremely popular among Chinese students) falling by 7% in the 2018–19 academic year. Meanwhile, mathematics and computer science jumped 9%, replacing business as the second most popular majors after engineering.[40]

In 2020, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and steps taken by the Trump administration to limit Chinese student enrollment, the number of students from mainland China being granted an F-1 visa dropped 99% compared to the previous year.[15] More broadly, a survey of over 700 institutions of higher learning revealed that the number of foreign students matriculating in the U.S. fell 43%.[41] However, 2023 data from IIE indicated a reversal of the trend of declining international student enrollment as it showed international student enrollment for the 2022-2023 academic year had exceeded pre-pandemic levels. The rate of the enrollment growth was the fastest in 40 years, with strong growth coming from India and sub-Saharan Africa.[42]

In Oceania[edit]

By the late 2010s, education has become Australia's fourth-largest export, after coal, iron ore, and natural gas. For Australia, foreign students are highly lucrative, bringing AU$9 billion into the Australian economy in 2018. That amount was also just over a quarter of the revenue stream for Australian universities. In 2019, Australian institutions of higher education welcomed 440,000 foreign students, who took up about 30% of all seats. 40% of non-Australian students hailed from China. In response to a surge in interest from prospective foreign students, Australian universities have invested lavishly in research laboratories, learning facilities, and art collections. Some senior bureaucrats saw their salaries rise tremendously. But the topic of international students is a contentious one in Australia. Proponents of accepting high numbers of foreign students said this was because the Australian government was not providing sufficient funding, forcing schools to take in more from other countries. Critics argued universities have made themselves too dependent on foreign revenue streams. In 2020, as SARS-CoV-2 spread around the globe, international travel restrictions were imposed, preventing foreign students from going to university in Australia, where the academic year begins in January. This proved to be a serious blow to the higher-education industry in Australia because it is more dependent on foreign students than its counterparts in other English-speaking countries. Australia's federal government excluded universities AU$60bn wage-subsidy scheme because it wanted to focus on domestic students, who, it said, will continue to receive funding. Federal and state governments were likely to provide relief to small regional institutions, but, like the big universities, they might need to shrink in order to survive.[43]

References[edit]

- ^ "Words We're Watching: 'Zoomer'". Merriam-Webster. January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ "zoomer". Dictionary.com. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Williams, Alex (September 19, 2015). "Meet Alpha: The Next 'Next Generation'". Fashion. The New York Times. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ June, Sophia (July 10, 2021). "Could Gen Z Free the World From Email?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ a b Worthman, Carol; Trang, Kathy (2018). "Dynamics of body time, social time and life history at adolescence". Nature. 554 (7693): 451–457. Bibcode:2018Natur.554..451W. doi:10.1038/nature25750. PMID 29469099. S2CID 4407844.

- ^ a b c Thomas, Leigh (December 3, 2019). "Education levels stagnating despite higher spending: OECD survey". World News. Reuters. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Strauss, Valerie (March 26, 2020). "1.5 billion children around globe affected by school closure. What countries are doing to keep kids learning during pandemic". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "PREVENTING A LOST DECADE: Urgent action to reverse the devastating impact of COVID-19 on children and young people" (PDF). Unicef. pp. 19–20. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Birrell, Hamish (November 17, 2020). "A golden age for universities will come to an end". The Economist. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ a b c Rushe, Dominic (September 7, 2018). "The US spends more on education than other countries. Why is it falling behind?". The Guardian. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Chhor, Khatya (December 8, 2016). "French students rank last in EU for maths, study finds". France24. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ DeSilver, Drew (February 15, 2017). "U.S. students' academic achievement still lags that of their peers in many other countries". Pew Research Center. Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ^ Rimfeld, Kaili; Kovas, Yulia; Dale, Philip S.; Plomin, Robert (July 23, 2015). "Pleiotropy across academic subjects at the end of compulsory education". Nature. 5 (11713): 11713. Bibcode:2015NatSR...511713R. doi:10.1038/srep11713. PMC 4512149. PMID 26203819.

- ^ Clynes, Tom (September 7, 2016). "How to raise a genius: lessons from a 45-year study of super-smart children". Nature. 537 (7619): 152–155. Bibcode:2016Natur.537..152C. doi:10.1038/537152a. PMID 27604932. S2CID 4459557.

- ^ a b Watanabe, Shin (November 4, 2020). "US visas for Chinese students tumble 99% as tensions rise". Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Covid-19 will be painful for universities, but also bring change". The Economist. August 8, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ Floch, Benoît (May 31, 2012). "Why do the French excel at maths? Thank the écoles normales supérieures". The Guardian. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ a b "How France created a university to rival MIT". The Economist. August 29, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c Davies, Pascale (June 27, 2018). "On Macron's orders: France will bring back compulsory national service". France. EuroNews. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Villeminot, Florence (July 11, 2019). "National civic service: A crash course in self-defence, emergency responses and French values". French Connection. France 24. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ "Poll says 80% of French want a return to national service". France 24. January 26, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- ^ Richardson, Hannah (July 2, 2012). "Boys' reading skills 'must be tackled'". BBC News. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Richardson, Hannah (May 17, 2011). "Boys 'can't read past 100th page', study says". BBC News. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Adams, Richard (April 19, 2018). "Teachers in UK report growing 'vocabulary deficiency'". The Guardian. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Busby, Eleanor (April 19, 2018). "Children's grades at risk because they have narrow vocabulary, finds report". Education. The Independent. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ a b Adams, Richard (September 28, 2017). "Almost half of all young people in England go on to higher education". Higher Education. The Guardian. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- ^ Turchin, Peter (July 2, 2008). "Arise 'cliodynamics'". Nature. 454 (7200): 34–5. Bibcode:2008Natur.454...34T. doi:10.1038/454034a. PMID 18596791. S2CID 822431.

- ^ Turchin, Peter (February 3, 2010). "Political instability may be a contributor in the coming decade". Nature. 403 (7281): 608. Bibcode:2010Natur.463..608T. doi:10.1038/463608a. PMID 20130632.

- ^ a b "Can too many brainy people be a dangerous thing?". The Economist. October 24, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Alphonso, Caroline (December 3, 2019). "Canadian high school students among top performers in reading, according to new international ranking". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ "Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA): Results from PISA 2018 – Canada" (PDF). OECD. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 18, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ Eaton, Sarah Elaine (January 15, 2020). "Cheating may be under-reported across Canada's universities and colleges". Education. The Conversation. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ "Why Generation Z has a totally different approach to money". World Economic Forum. November 30, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- ^ Krupnick, Matt (August 29, 2017). "After decades of pushing bachelor's degrees, U.S. needs more tradespeople". PBS Newshour. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Paterson, James (July 3, 2018). "Yet another report says fewer Americans value 4-year degree". Education Dive. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ "So You Have a Liberal Arts Degree and Expect a Job?". PBS Newshour. January 3, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Solman, Paul (March 28, 2019). "Anxious about debt, Generation Z makes college choice a financial one". PBS Newshour. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ Aragon, Cecilia (December 27, 2019). "What I learned from studying billions of words of online fan fiction". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Wai, Jonathan; Makel, Matthew C. (September 4, 2015). "How do academic prodigies spend their time and why does that matter?". The Conversation. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ Binkey, Collin (November 18, 2019). "US draws fewer new foreign students for 3rd straight year". Associated Press. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ Korn, Melissa (November 16, 2020). "New International Student Enrollment Plunges 43% This Fall". Education. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ Anderson, Nick (November 13, 2023). "With surge from India, international students flock to United States". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Australia's foreign-student bubble has burst". Asia. The Economists. May 28, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2020.