Engolo

| Also known as | ngolo, engolo, angolo, angola |

|---|---|

| Focus | kicks, evasions, takedowns, handstands, jumps |

| Country of origin | Angola |

| Date of formation | pre-colonial times |

| Descendant arts | capoeira knocking and kicking danmyé |

| Meaning | strength, power |

N'golo (anglicized as Engolo) is a traditional Bantu martial art and game from Angola, that combines elements of combat and dance, performed in a circle accompanied by music and singing. It is known as the forerunner of capoeira.

Engolo has been played in Africa for centuries, specifically along the Cunene River in the Cunene Province of Angola.[1] Ngolo finds its inspiration in nature, involving the imitation of animal behaviors. Examples include mimicking a zebra's kicking motion[2] or emulating the swaying of trees.[3] This warrior dance is not merely ritualistic; serious injuries have been known to occur during its practice.[3]

The combat style of engolo encompasses a variety of techniques, including different types of kicks, dodges, and takedowns, with a particular emphasis on inverted positions. Many of the iconic capoeira techniques, such as meia lua de compasso, scorpion kick, chapa, chapa de costas, rasteira, L-kick, and others, were originally developed within engolo.[3] As African slaves were transported to Brazil, they brought engolo with them, and through the centuries, it evolved into the capoeira.[4]

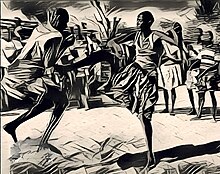

Engolo was "rediscovered" in 1950s when the Angolan artist Albano Neves e Sousa included it in a collection of drawings, highlighting its similarities to the Afro-Brazilian martial art of Capoeira.[5]

Engolo is one of several African martial arts spread to the Americas through the African Diaspora. It descendant arts include knocking and kicking in North America, capoeira in Brazil, and danmyé in Martinique.[6] Known sources document only one African combat game beside engolo that uses similar kicking techniques – moraingy on Madagascar and surrounding islands.[7]

Name[edit]

The term ngolo derived from the Kikongo Bantu language and signifies concepts related to strength, power, and energy.[8] Moreover, in the 15th century, ngola was a title held by African kings. The term ngolo originates from a Bantu root *-gol, meaning to bend or twist.[9]

Ngolo is also colloquially referred to as the Zebra dance.[10]

Music[edit]

In West Central Africa, martial arts naturally take the form of dance. In Bantu culture, dance is an integral part of daily life. People danced while working, playing, praying, mourning, and celebrating. In Congo-Angola, dance is intricately linked to song, music, and ritual, and even incorporated into wartime preparations and battles.[11]

Engolo is typically performed within a circle, accompanied by percussion, with participants humming, singing, and clapping hands.[12] The dance synchronizes with the rhythm of handclaps. In Jogo de corpo documentary, sometimes the musical bow was also played (with mouth).[3]

One of the traditional song in engolo is: “Who dies in engolo won’t be wept for”. There are also alternative translation from Kimbundu language: [13]

| Kimbundu | English translation |

|---|---|

|

Wankya kengolo mutanbo kwapkwapo |

Who is killed (struck down) in engolo does not make a wake |

Another engolo song highlightes the all-important ability to dodge and escape: “Kauno tchivelo kwali tolondo”, meaning “You don’t have a door, maybe jump over”, emphasizing agility in evasions and cunning in finding creative solutions to challenges.[14]

Engolo circle[edit]

Within the Bantu culture, the circle carries profound symbolism. Village dwellings are frequently arranged in circular formations, and communal meals are enjoyed while seated in a circle.[15] Dancing in a circle holds significance, representing protection and strength, symbolizing the bond with the spirit world, life, and the divine.[15]

The practice of engolo, as documented in the 1950s, involves a circle of singing participants and potential combatants, and, similar to a capoeira roda, participants must remain within a defined area.[5] Sometimes, this circle is overseen by a kimbanda, a ritual specialist. The game starts with clapping and call-and-response songs, some of them featuring humming instead of lyrics.[12] A practitioner enters the circle, dancing and shouting, and when another participant joins, they engage in a dance-off, assessing each other's skills. This interaction incorporates kicks and sweeps, with defenders using dodges and blending techniques to counterattack smoothly. This cycle continues until one participant concedes defeat, feels the match is complete, or the kimbanda overseeing the match calls for its conclusion.[16]

In engolo games documented in the 2010s, players often initiate the engolo circle by challenging others. In such cases, they enthusiastically leap into the circle, showcasing agile movements and occasional shouts while awaiting someone to join and engage in the play. They can also select a specific individual to join them by using kicks or simulated kicks.[17]

History[edit]

The origin of engolo[edit]

There is no written record of engolo's origin. Engolo practitioners claim that "engolo comes from the ancestors"[6] and that their fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers played engolo.[3]

According to Desch-Obi, engolo was likely developed by Bantu shamans and warriors in ancient Angola,[18] based on the inverted worldview of kongo religion.[19] With this worldview, shamans put themselves upside down to gain power from the ancestral realm.[20] Among the Pende shamans, the most used movement was the front crescent kick.[20] Masked shaman kicked over sacred medicine to activate it and over the kneeling people to heal them.[20] Moreover, engolo was a military training method to develop warriors' close combat skills.[12]

Neves e Sousa believes that the techniques of engolo derived from the way in which zebras fight among themselves. Desch-Obi finds that using the zebra as a combat role model in Angola makes sense because it symbolizes nimbleness and agile defense. The engolo also resembled the zebra's fighting style, particularly the zebra kicks executed with the palms touching the ground, which is a defining feature of engolo.[9]

Matthew Zylstra suggests that a dance performed by the Gwikwe Bushmen bears a striking resemblance to the Angolan art. He proposes a theory that the Bantu peoples in southern Angola, who interacted with San Bushmen groups in the region, may have known such dances and integrated them into their cultures. If this theory holds, it would imply that the origins of engolo could be thousands of years old.[2]

Engolo in Africa[edit]

In precolonial Angola, mock combats were a major part of military training, and since hand-to-hand combat was essential to warfare, techniques to avoid blows and attacks were a key focus of martial exercises.[21]

Since the Portuguese invasion in the 16th century, European chroniclers noted the martial skills of the local people. Mock combats were a common feature of military reviews in Kongo/Angola, similar to drills in Europe.[21] These movements could be applied in warfare, as Angolan warriors heavily relied on personal maneuvers in their fighting technique.[21] Written sources from the 16th century describe martial arts similar to capoeira.[22] A Jesuit missionary in late 16th century described the abilities of the Ndongo warriors as follows:

They do not have defensive arms, all their defense rests in sanguar, which is to jump from one place to another with a thousand twists and such agility that they can dodge arrows and spears.[23]

In the mid-17th century, Italian missionary Cavazzi also described the handstand technique of Angolan nganga:

To augment the reputation of his excellency, he frequently walks turned upside down, with his hands on the ground and his feet in the air."[20]

In 17th century, new military formation of kilombo, a fortified war camp surrounded by a wooden palisade, appeared among Imbangala warriors, which would soon be used in Brazil by freed Angolans.[24] Angolan warriors mostly fought without shields, so evasion was essential to survive in missile and close combat. In the 19th century, Angolan warriors excelled in close combat techniques, surpassing Europeans.[25]

In the early 20th century, Portuguese ethnographer Augusto Bastos documented a capoeira-like combat game in the Benguela district:

The Quilengues have an exercise, which they call ómudinhu. It consists in prodigious jumps in which they throw the legs into the air and the head downward. It is accompanied by strong hand clapping.[26]

In the 1950s, "n'golo dance" was first documented when the painter Neves e Sousa visited Mucope, in Cunene Province. In his drawings, young men in their prime can be seen performing inverted kicks and challenging acrobatic moves. His engolo drawings show many of the foundational capoeira moves, including the chapa de costas, rabo de arraia, scorpion, and cartwheel kick.[27]

During the 1990s martial arts scholar Desch-Obi undertook field research in Angola, documenting engolo techniques.[28] Around 2010, as a result of a research project, a documentary was made about engolo Jogo de Corpo. This time, all engolo players were elderly individuals who used only a basic set of kicks and sweeps, without demanding acrobatics. They stated that engolo had not been actively played since the 1970s because of Angolan Civil War (1975–2002), and that youth were no longer learning engolo.[3]

Engolo in Americas[edit]

The art of engolo spread from Africa to the Americas, mainly among slaves taken from Angola and transported to the colonies via the Atlantic slave trade routes. The art has been maintained for centuries, and its traces have survived to this day among the African diaspora. It descendant arts include knocking and kicking in North America, danmyé in Martinique and capoeira in Brazil.[6] Knocking and kicking was secretly practiced in the states of South Carolina and Virginia, during the times of slavery in the United States. Angolans were the predominant portion of the slaves in South Carolina.[29] Gwaltney characterizes knocking and kicking as "the ancient martial art practiced by clergy among the enslaved and their followers."[30] The "clergy" of the old African religion was known as nganga in Congo/Angola. These clandestine gatherings were often referred to as "drum meetings."[30]

The danmyé or ladja is a martial art from Martinique that is similar to capoeira.[31] The term danmyé likely came from the drumming technique danmyé, played during the combat.[32] The art was influenced by various combat techniques from West and Central Africa, including West African wrestling, but the core kicking techniques comes from ngolo.[31] In the 1930s Katherine Dunham filmed the ladja matches. In that time, wrestling was not the dominant technique of ladja, but kicks, many of them inverted, and a significant number of hand strikes from kokoyé.[33]

Engolo in Brazil[edit]

Well, there is one thing that nobody doubts: the ones to teach capoeira to us were the negro slaves that were brought from Angola.[34]

From the 16th century, Portuguese colonists began capturing slaves from Angola and transporting them to Brazil. In 1617, they established a colony in Benguela. In 1627 and 1628, they conducted two significant military campaigns: one ventured towards the source of the Cunene River, and the other explored the central territories inhabited by the Cunene people.[35]

Soon freed slaves started founding settlements in remote areas, calling them kilombo, meaning a war camp in the Kimbundu Bantu language.[36] Portuguese sources mentioned that it took more than one dragoon to capture a quilombo warrior, as they defended themselves with a "strangely moving fighting technique".[37] Some quilombos grew into independent states, with the largest, Quilombo dos Palmares, lasting nearly a century (1605-1694) as an African Kingdom in the Western Hemisphere.[37]

One of the first records of inverted kicks in Brazil is from 18th-century Bahia. The Inquisition case reported of a free African named João, who had the ability to become "possessed" and communicate with the ancestors. To accomplish this, he would need to "walk on one foot, throwing the other one violently over his shoulder."[38] By the mid-18th century, ngolo had spread to Rio de Janeiro and other cities.[39] The term playing angola was also used for the art, where both angola and engolo actually came from the same Bantu word.[8]

Any display of not only martial arts but mere acrobatics among Africans was forbidden.[40] During the 1780s, a free negro in Rio was accused of "witchcraft" before the Inquisition. One indicator of his role as a witch doctor was his ability of hand walking.[38] Due to repression, angola was forced to be passed down as secret knowledge.

As the end of the 18th century, the Angolan fighting technique in Brazil started to be called capoeira,[41] named after the clearings in the forest where freed slaves resided and practice its skills.[42]

Evolution to capoeira[edit]

During the 19th century, the street capoeiragem in Rio became associated with gangs and very different from the original Angolan art, including hand strikes, head butts, clubs and daggers.

In the early 20th century, Anibal Burlamaqui and Agenor Moreira Sampaio first codified the street version of capoeira as a national martial art, removing music and dance and incorporating strikes from boxing, judo and other disciplines. In the 1930s, Mestre Bimba founded the regional style of capoeira in Salvador, Bahia, incorporating traditional elements of music and dance, as well as new elements from other martial arts. Finally, in the 1940s, in response to the popularization of corrupted forms of capoeira, Mestre Pastinha founded the Capoeira angola school, returning capoeira to its African roots.

Modern capoeira remains firmly based on crescent and pushing kicks (often from inverted positions), sweeps, and acrobatic evasions inherited from engolo.[43] Professor Desch-Obi finds that the evolution from engolo to capoeira took place within a relatively isolated context, because the Portuguese lacked prevalent unarmed martial art to blend with. Some punching and grappling techniques were used in street combat, but they were not incorporated into the philosophy, aesthetics and rituals of capoeira. The sole new form incorporated in engolo was headbutting, derived from a distinct African practice known as jogo de cabeçadas. Headbutts was a major component of the street-fighting capoeira in Rio, but only a few butts entered the regular practice.[44]

One observer remarked that "the Brazilian capoeira is nothing other than our engolo done to different songs."[45] Also, the angolan painter Neves e Sousa, who drew engolo games in Mucope, visited Brazil in 1960s asserting that "N’golo is capoeira".[2]

Techniques[edit]

For a person to be good at engolo, he needs to have a light heart. If he receives a strong kick, and he is bad, he will try to fight. And then he does not learn well.[17]

— Kahani Waupeta

Engolo players use casual terms like mussana and ngatussana for kicks and koyola for dragging or pulling, without a formalized kick-naming system seen in martial arts.[17]

Base step[edit]

Engolo's movements are rooted in the specific fundamental jumping moves, that serve as the foundation for offensive and evasive maneuvers. In contrast to capoeira ginga, engolo jumps can attain remarkable heights, often honed through exercises like jumping cattle fences.[17]

Kicks[edit]

In contrast to the quick, snapping kicks commonly found in Asian martial arts, engolo predominantly features circular or crescent kicks. When straight kicks are employed, they are usually pushing kicks. Engolo's distinctive set of moves prominently includes inverted kicks in the handstand position.[13]

Push kicks (chapas)[edit]

There are several types of push kicks in engolo including: [27][17]

- front push kick (chapa de frente)

- back push kick (chapa de costas)

- side push kick (chapa lateral)

- revolving push kick (chapa giratoria)

- push kick from inverted position

Engolo players often do a rotation with a back push kick, with or without jumping.[17]

Crescent kicks (meia lua)[edit]

Front crescent kick is one of the basic engolo kick, documented both in 20th and 21st century. There are numerous variations of this basic kick in engolo: [17]

- front crescent kick (okupayeka,[20] pt. meia lua de frente)

- high front crescent

- medium front crescent

- jumping front crescent

- reversed front crescent (queixada)

- back crescent kick (armada)

The leg used for kicking can be extended fully or partially bent.[17]

Rabo de arraia[edit]

What most clearly connects engolo and capoeira is a specific crescent kick known as Rabo de arraia or Meia lua de compasso, which is extremely rare in other martial systems.[17] This kick combines an evasive maneuver with a reverse roundhouse kick, and was first documented in Angola in the works of Neves e Sousa, in the mid-20th century.

The Bantu name for this technique is okuminunina / okusanene komima (crescent kicks with hands on ground).[14]

Roundhouse kick (martelo)[edit]

Some of the most seasoned engolo players, like Kahani, do a martelo while jumping in the air.[17]

Back hook kick[edit]

Engolo practitioners employ a hooking kick executed from behind, resembling the capoeira move known as gancho de costas. This particular kick is employed when the adversary's upper torso is in close proximity to one's own body. As Muhalambadje demonstrates in the Jogo de corpo documentary (2014), this is a very dangerous technique.[17]

Scorpion kick[edit]

Scorpion kick is one of the distinct engolo kicks, first documented in early drawings from 20th century.[46] It is not so common among today's old practitioners, but they are known how to execute it when asked.[3]

Cartwheel kicks[edit]

Various kicking cartwheel techniques were documented in engolo since the 1950s. The Bantu name for this kicking techniques is okusanena-may-ulu (cartwheel or handstand kick).[14]

The L-kick is executed by throwing the body into a cartwheel motion, but rather than completing the wheel, the body flexes, while supported by one hand on the ground. One leg is brought downward and deliver a kick, while the other remains in the air. One of Neves e Sousa’s drawings clearly shows this technique.[17]

The Buntu name for the techniques is okusana omaulo-ese (cartwheel or handstand kick down).[14]

Evasions[edit]

The core of engolo lies in the practitioner's ability to defend themselves through agile movements like ducking, twisting, and leaping.[11]

Unlike defensive maneuvers seen in Angolan kandeka slapboxing, engolo does not include blocking movements. Instead, skilled practitioners must gracefully evade attacks by going over, under, or employing fluid, evasive techniques. Some of the common evasive techniques are:

- defensive squat[47]

- spinning away from kick[47]

- angling away from kick[48]

- falling back escape[47]

- escape with cartwheel (okuyepa)[14]

Assunção finds that contemporary engolo employs five fundamental evasions against kicks, including: [17]

- defensive squat (dodge under the opponent's kick by lowering the head and guarding the face with an arm)

- high escape (escape while keeping the body upright)

- jump escape (with one or both arms raised or even with the counter kick)

- short jump escape (guard with one hand while do a brief jump to move the body out of the kick's range)

- entering into the opponent's kick (while guarding the face)

Takedowns[edit]

Another set of movements distinct for engolo includes foot sweeps. Few basic types are:

Four variations of sweeps or takedowns were documented during engolo game in the 2010s:[17]

- a lateral sweeping kick resembling the capoeira banda, causing the opponent's foot to lift off the ground, leading to a fall.

- a rasteira, where one strategically places their instep behind the adversary's standing heel and then pulls or drags forward to disrupt their balance.

- a defending sweep against the opponent's rasteira (observed during lessons but rarely used in gameplay).

- a rasteira targeting the opponent's knee.

Acrobatics[edit]

Documented acrobatics techniques in engolo includes: [51]

Engolo using handstands and cartwheels both for kicks and evasive maneuvers. Multiple early drawings clearly demonstrates these techniques.[27]

Initiation[edit]

The one who taught me was a man called Francisco Tchibelembembe, but he already died. He taught me, and also led the ritual through which I was initiated to the spirit.[17]

— Kahani Waupeta

Spirituality[edit]

Inverted worldview[edit]

Kalûnga in Kongo religion represents the idea that in the realm of the living everything is reversed from the realm of the ancestors. Where men walk on their feet, the spirits walk on their hands; where men are black, the spirits are white; where men reach physical abilities, the ancestors reach spirituality.[52] Dweller of the ancestral realm are inverted compared to us, as viewed from our mirrored perspective.[52] With this worldview, practitioners of African martial arts deliberately invert themselves upside down to emulate the ancestors, and to draw power from the ancestral realm.[52][53]

Spirit possession[edit]

I initiated with the spirit when I was already ill. They said it was my grandfather Mukwya. I did not know him. I was already an engolo dancer when the spirit found me.[17]

— Kahani Waupeta

An integral aspect of engolo game is incorporation of ancestral spirit. Historical accounts document that certain Engolo players underwent a ritual of spirit possession (oktonkheka) guided by their engolo teachers. All engolo players unanimously agreed that this connection typically extended to a family member who had previously engaged in engolo and had developed a distinct bond with the descendant they are presently embodying.[17]

My friend, if you see me dancing, you will say, "What is happening to this old man?" You will pay attention, because you know what my way of dancing is. You will only get scared when I'm crying. You will feel the heat. People can ask me questions; I won't say a word. I will only speak later on.[17]

— Munekavela Katumbela

When a player is possessed by a spirit, this transformation may not manifest immediately, as they continue with the game, maybe playing even better than usual. However, the shift in their behavior becomes evident to the audience, especially in their communication.[17]

Engolo as a part of rituals[edit]

Painter Neves e Sousa described engolo as part of a rite of passage (efico and omuhelo), wherein young boys competed for a bride.[54] Desch-Obi finds that engolo is not a part of any specific ritual but was often performed during community celebrations or rites. At other times, it might be employed for dueling, self-defense, or merely a recreation.[12]

Interpretations[edit]

Professor Matthias Röhrig Assunção posits that the Nkhumbi are the sole ethnic group in Angola known for practicing engolo. He questions why a practice limited to such a small ethnic group would have spread in Brazil. He suggests that two hypotheses about capoeira's origin are plausible:[17]

- It may have resulted from related Angolan combat games brought to Brazilian ports and merged into capoeira. However, there's no evidence of engolo-like practices among other Angolan groups.

- Alternatively, a small Nkhumbi group could have laid the foundation for capoeira, incorporating contributions from other Africans. This raises questions about how such a minority could influence a broader enslaved community, although similar cultural evolutions have occurred before.[17]

Professor Desch-Obi finds that engolo was transferred to Brazil similar to how modern martial arts are transmitted. He suggests martial arts could spread with just a "few practitioners introduced to a region".[55]

Literature[edit]

- Assunção, Matthias Röhrig (2002). Capoeira: The History of an Afro-Brazilian Martial Art. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-8086-6.

- Desch-Obi, M. Thomas J. (2008). Fighting for Honor: The History of African Martial Art Traditions in the Atlantic World. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-718-4.

- Talmon-Chvaicer, Maya (2008). The Hidden History of Capoeira: A Collision of Cultures in the Brazilian Battle Dance. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71723-7.

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Engolo-Angola".

- ^ a b c Matthew Zylstra, The real origins of capoeira?

- ^ a b c d e f g The documentary Jogo de Corpo. Capoeira e Ancestralidade (2013) by Matthias Assunção and Mestre Cobra Mansa provides insights into this development.

- ^ Capoeira: Afro-Brazilian Dance of Freedom

- ^ a b THE VISIT OF ALBANO NEVES E SOUSA

- ^ a b c Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 2.

- ^ Assunção 2002, pp. 45.

- ^ a b https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/ngolo

- ^ a b Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 38.

- ^ Body Games

- ^ a b Talmon-Chvaicer 2008, pp. 29.

- ^ a b c d Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 36.

- ^ a b Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 40.

- ^ a b c d e Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 43.

- ^ a b Talmon-Chvaicer, M. (2004). Verbal and Non-Verbal Memory in Capoeira. Sport in Society, 7(1), 49–68. doi:10.1080/1461098042000220182

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Matthias Röhrig Assunção, Engolo and Capoeira. From Ethnic to Diasporic Combat Games in the Southern Atlantic

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 17, 39.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 37.

- ^ a b c d e Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 39.

- ^ a b c Assunção 2002, pp. 47.

- ^ Talmon-Chvaicer 2008, pp. 19.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 45.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 21.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Assunção 2002, pp. 53.

- ^ a b c Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 219–224.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 291.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 77.

- ^ a b Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 107–8.

- ^ a b Assunção 2002, pp. 62.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 277.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 279.

- ^ "It's a fight, it's a dance, it's Capoeira". Realidade. February 1967 – via velhosmestres.com.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 47.

- ^ A. de Assis Junior, "Kilómbo", Dicionário kimbundu-português, Luanda Argente, Santos, p. 127

- ^ a b Gomes, Flávio (2010). Mocambos de Palmares; histórias e fontes (séculos XVI–XIX) (in Portuguese). Editora 7 Letras. ISBN 978-85-7577-641-4.

- ^ a b Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 163.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Desch-Obi, T. J. "Capoeira." Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History, edited by Colin A. Palmer, 2nd ed., vol. 2, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 395–398. Gale eBooks, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3444700236/GVRL?u=tamp44898&sid=GVRL&xid=fe4652ba. Accessed 19 January 2021.

- ^ Its very first mention dating back only to 1789 [Cavalcanti 2004: 201–2]

- ^ https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/capoeira#Etymology_2_2

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 154.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 207.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 317.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 222, 223.

- ^ a b c Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 220.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 221.

- ^ a b Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 86.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 224.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 219.

- ^ a b c Obadele Bakari Kambon, Afrikan=Black Combat Forms Hidden in Plain Sight: Engolo/Capoeira, Knocking-and-Kicking and Asafo Flag Dancing

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 3.

- ^ Da minha África e do Brasil que eu vi, Albano Neves e Sousa. Angola: Ed. Luanda.

- ^ Desch-Obi 2008, pp. 78.