Frederick Sanger

Frederick Sanger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 13 August 1918 Rendcomb, Gloucestershire, England |

| Died | 19 November 2013 (aged 95) |

| Alma mater | St John's College, Cambridge (BA, PhD) |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse | Margaret Joan Howe[4] |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biochemistry |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | The metabolism of the amino acid lysine in the animal body (1943) |

| Doctoral advisor | Albert Neuberger[1] |

| Doctoral students | |

Frederick Sanger OM CH CBE FRS FAA (/ˈsæŋər/; 13 August 1918 – 19 November 2013) was a British biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice.

He won the 1958 Chemistry Prize for determining the amino acid sequence of insulin and numerous other proteins, demonstrating in the process that each had a unique, definite structure; this was a foundational discovery for the central dogma of molecular biology.

At the newly constructed Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, he developed and subsequently refined the first-ever DNA sequencing technique, which vastly expanded the number of feasible experiments in molecular biology and remains in widespread use today. The breakthrough earned him the 1980 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, which he shared with Walter Gilbert and Paul Berg.

He is one of only three people to have won multiple Nobel Prizes in the same category (the others being John Bardeen in physics and Karl Barry Sharpless in chemistry),[5] and one of five persons with two Nobel Prizes.

Early life and education[edit]

Frederick Sanger was born on 13 August 1918 in Rendcomb, a small village in Gloucestershire, England, the second son of Frederick Sanger, a general practitioner, and his wife, Cicely Sanger (née Crewdson).[6] He was one of three children. His brother, Theodore, was only a year older, while his sister May (Mary) was five years younger.[7] His father had worked as an Anglican medical missionary in China but returned to England because of ill health. He was 40 in 1916 when he married Cicely, who was four years younger. Sanger's father converted to Quakerism soon after his two sons were born and brought up the children as Quakers. Sanger's mother was the daughter of an affluent cotton manufacturer and had a Quaker background, but was not a Quaker.[7]

When Sanger was around five years old the family moved to the small village of Tanworth-in-Arden in Warwickshire. The family was reasonably wealthy and employed a governess to teach the children. In 1927, at the age of nine, he was sent to the Downs School, a residential preparatory school run by Quakers near Malvern. His brother Theo was a year ahead of him at the same school. In 1932, at the age of 14, he was sent to the recently established Bryanston School in Dorset. This used the Dalton system and had a more liberal regime which Sanger much preferred. At the school he liked his teachers and particularly enjoyed scientific subjects.[7] Able to complete his School Certificate a year early, for which he was awarded seven credits, Sanger was able to spend most of his last year of school experimenting in the laboratory alongside his chemistry master, Geoffrey Ordish, who had originally studied at Cambridge University and been a researcher in the Cavendish Laboratory. Working with Ordish made a refreshing change from sitting and studying books and awakened Sanger's desire to pursue a scientific career.[8] In 1935, prior to heading off to college, Sanger was sent to Schule Schloss Salem in southern Germany on an exchange program. The school placed a heavy emphasis on athletics, which caused Sanger to be much further ahead in the course material compared to the other students. He was shocked to learn that each day was started with readings from Hitler's Mein Kampf, followed by a Sieg Heil salute.[9]

In 1936 Sanger went to St John's College, Cambridge, to study natural sciences. His father had attended the same college. For Part I of his Tripos he took courses in physics, chemistry, biochemistry and mathematics but struggled with physics and mathematics. Many of the other students had studied more mathematics at school. In his second year he replaced physics with physiology. He took three years to obtain his Part I. For his Part II he studied biochemistry and obtained a 1st Class Honours. Biochemistry was a relatively new department founded by Gowland Hopkins with enthusiastic lecturers who included Malcolm Dixon, Joseph Needham and Ernest Baldwin.[7]

Both his parents died from cancer during his first two years at Cambridge. His father was 60 and his mother was 58. As an undergraduate Sanger's beliefs were strongly influenced by his Quaker upbringing. He was a pacifist and a member of the Peace Pledge Union. It was through his involvement with the Cambridge Scientists' Anti-War Group that he met his future wife, Joan Howe, who was studying economics at Newnham College. They courted while he was studying for his Part II exams and married after he had graduated in December 1940. Sanger, although brought up and influenced by his religious upbringing, later began to lose sight of his Quaker related ways. He began to see the world through a more scientific lens, and with the growth of his research and scientific development he slowly drifted farther from the faith he grew up with. He has nothing but respect for the religious and states he took two things from it, truth and respect for all life.[10] Under the Military Training Act 1939 he was provisionally registered as a conscientious objector, and again under the National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939, before being granted unconditional exemption from military service by a tribunal. In the meantime he undertook training in social relief work at the Quaker centre, Spicelands, Devon and served briefly as a hospital orderly.[7]

Sanger began studying for a PhD in October 1940 under N.W. "Bill" Pirie. His project was to investigate whether edible protein could be obtained from grass. After little more than a month Pirie left the department and Albert Neuberger became his adviser.[7] Sanger changed his research project to study the metabolism of lysine[11] and a more practical problem concerning the nitrogen of potatoes.[12] His thesis had the title, "The metabolism of the amino acid lysine in the animal body". He was examined by Charles Harington and Albert Charles Chibnall and awarded his doctorate in 1943.[7]

Research and career[edit]

Sequencing insulin[edit]

Neuberger moved to the National Institute for Medical Research in London, but Sanger stayed in Cambridge and in 1943 joined the group of Charles Chibnall, a protein chemist who had recently taken up the chair in the Department of Biochemistry.[13] Chibnall had already done some work on the amino acid composition of bovine insulin[14] and suggested that Sanger look at the amino groups in the protein. Insulin could be purchased from the pharmacy chain Boots and was one of the very few proteins that were available in a pure form. Up to this time Sanger had been funding himself. In Chibnall's group he was initially supported by the Medical Research Council and then from 1944 until 1951 by a Beit Memorial Fellowship for Medical Research.[6]

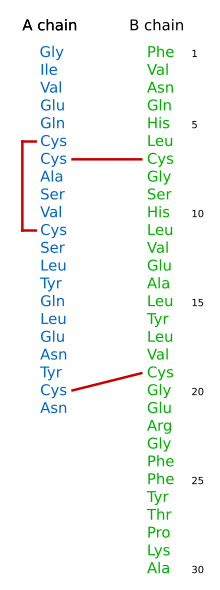

Sanger's first triumph was to determine the complete amino acid sequence of the two polypeptide chains of bovine insulin, A and B, in 1952 and 1951, respectively.[15][16] Prior to this it was widely assumed that proteins were somewhat amorphous. In determining these sequences, Sanger proved that proteins have a defined chemical composition.[7]

To get to this point, Sanger refined a partition chromatography method first developed by Richard Laurence Millington Synge and Archer John Porter Martin to determine the composition of amino acids in wool. Sanger used a chemical reagent 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (now, also known as Sanger's reagent, fluorodinitrobenzene, FDNB or DNFB), sourced from poisonous gas research by Bernard Charles Saunders at the Chemistry Department at Cambridge University. Sanger's reagent proved effective at labelling the N-terminal amino group at one end of the polypeptide chain.[17] He then partially hydrolysed the insulin into short peptides, either with hydrochloric acid or using an enzyme such as trypsin. The mixture of peptides was fractionated in two dimensions on a sheet of filter paper, first by electrophoresis in one dimension and then, perpendicular to that, by chromatography in the other. The different peptide fragments of insulin, detected with ninhydrin, moved to different positions on the paper, creating a distinct pattern that Sanger called "fingerprints". The peptide from the N-terminus could be recognised by the yellow colour imparted by the FDNB label and the identity of the labelled amino acid at the end of the peptide determined by complete acid hydrolysis and discovering which dinitrophenyl-amino acid was there.[7]

By repeating this type of procedure Sanger was able to determine the sequences of the many peptides generated using different methods for the initial partial hydrolysis. These could then be assembled into the longer sequences to deduce the complete structure of insulin. Finally, because the A and B chains are physiologically inactive without the three linking disulfide bonds (two interchain, one intrachain on A), Sanger and coworkers determined their assignments in 1955.[18][19] Sanger's principal conclusion was that the two polypeptide chains of the protein insulin had precise amino acid sequences and, by extension, that every protein had a unique sequence. It was this achievement that earned him his first Nobel prize in Chemistry in 1958.[20] This discovery was crucial to the later sequence hypothesis of Francis Crick for developing ideas of how DNA codes for proteins.[21]

Sequencing RNA[edit]

From 1951 Sanger was a member of the external staff of the Medical Research Council[6] and when they opened the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in 1962, he moved from his laboratories in the Biochemistry Department of the university to the top floor of the new building. He became head of the Protein Chemistry division.[7]

Prior to his move, Sanger began exploring the possibility of sequencing RNA molecules and began developing methods for separating ribonucleotide fragments generated with specific nucleases. This work he did while trying to refine the sequencing techniques he had developed during his work on insulin.[21]

The key challenge in the work was finding a pure piece of RNA to sequence. In the course of the work he discovered in 1964, with Kjeld Marcker, the formylmethionine tRNA which initiates protein synthesis in bacteria.[22] He was beaten in the race to be the first to sequence a tRNA molecule by a group led by Robert Holley from Cornell University, who published the sequence of the 77 ribonucleotides of alanine tRNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae in 1965.[23] By 1967 Sanger's group had determined the nucleotide sequence of the 5S ribosomal RNA from Escherichia coli, a small RNA of 120 nucleotides.[24]

Sequencing DNA[edit]

Sanger then turned to sequencing DNA, which would require an entirely different approach. He looked at different ways of using DNA polymerase I from E. coli to copy single stranded DNA.[25] In 1975, together with Alan Coulson, he published a sequencing procedure using DNA polymerase with radiolabelled nucleotides that he called the "Plus and Minus" technique.[26][27] This involved two closely related methods that generated short oligonucleotides with defined 3' termini. These could be fractionated by electrophoresis on a polyacrylamide gel and visualised using autoradiography. The procedure could sequence up to 80 nucleotides in one go and was a big improvement on what had gone before, but was still very laborious. Nevertheless, his group were able to sequence most of the 5,386 nucleotides of the single-stranded bacteriophage φX174.[28] This was the first fully sequenced DNA-based genome. To their surprise they discovered that the coding regions of some of the genes overlapped with one another.[2]

In 1977 Sanger and colleagues introduced the "dideoxy" chain-termination method for sequencing DNA molecules, also known as the "Sanger method".[27][29] This was a major breakthrough and allowed long stretches of DNA to be rapidly and accurately sequenced. It earned him his second Nobel prize in Chemistry in 1980, which he shared with Walter Gilbert and Paul Berg.[30] The new method was used by Sanger and colleagues to sequence human mitochondrial DNA (16,569 base pairs)[31] and bacteriophage λ (48,502 base pairs).[32] The dideoxy method was eventually used to sequence the entire human genome.[33]

Postgraduate students[edit]

During the course of his career Sanger supervised more than ten PhD students, two of whom went on to also win Nobel Prizes. His first graduate student was Rodney Porter who joined the research group in 1947.[2] Porter later shared the 1972 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Gerald Edelman for his work on the chemical structure of antibodies.[34] Elizabeth Blackburn studied for a PhD in Sanger's laboratory between 1971 and 1974.[2][35] She shared the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Carol W. Greider and Jack W. Szostak for her work on telomeres and the action of telomerase.[36]

Sanger's rule[edit]

... anytime you get technical development that’s two to threefold or more efficient, accurate, cheaper, a whole range of experiments opens up.[37]

This rule should not be confused with Terence Sanger's rule, which is related to Oja's rule.

Awards and honours[edit]

As of 2015[update], Sanger is one of the only two people to have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice (the other being Karl Barry Sharpless in 2001 and 2022), and one of only five two-time Nobel laureates: The other four were Marie Curie (Physics, 1903 and Chemistry, 1911), Linus Pauling (Chemistry, 1954 and Peace, 1962), John Bardeen (twice Physics, 1956 and 1972), and Karl Barry Sharpless (twice Chemistry, 2001 and 2022).[5]

- Elected Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1954[2]

- Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) – 1963[2]

- Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH) – 1981[2]

- Member of the Order of Merit (OM) – 1986[2]

- Corresponding Member of the Australian Academy of Science – 1982[2]

- William Bate Hardy Prize – 1976[2]

- Nobel Prize in Chemistry – 1958, 1980[20][30]

- Corday–Morgan Medal – 1951[2]

- Royal Medal – 1969[2]

- Gairdner Foundation International Award – 1971[2]

- Copley Medal – 1977[2]

- G.W. Wheland Award – 1978[2]

- Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize of Columbia University – 1979[2]

- Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research – 1979[2]

- Association of Biomolecular Resource Facilities Award – 1994[38]

- Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement – 2000[39][40]

- Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award from the Division of History of Chemistry of the American Chemical Society – 2016[41][42][29]

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (formerly the Sanger Centre) is named in his honour.[2]

Personal life[edit]

Marriage and family[edit]

Sanger married Margaret Joan Howe (not to be confused with Margaret Sanger, the American pioneer of birth control) in 1940. She died in 2012. They had three children — Robin, born in 1943, Peter born in 1946 and Sally Joan born in 1960.[6] He said that his wife had "contributed more to his work than anyone else by providing a peaceful and happy home."[43]

Later life[edit]

Sanger retired in 1983, aged 65, to his home, "Far Leys", in Swaffham Bulbeck outside Cambridge.[2]

In 1992, the Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council founded the Sanger Centre (now the Sanger Institute), named after him.[44] The institute is on the Wellcome Trust Genome Campus near Hinxton, only a few miles from Sanger's home. He agreed to having the Centre named after him when asked by John Sulston, the founding director, but warned, "It had better be good."[44] It was opened by Sanger in person on 4 October 1993, with a staff of fewer than 50 people, and went on to take a leading role in the sequencing of the human genome.[44] The Institute had about 900 people in 2020 and is one of the world's largest genomic research centres.

Sanger said he found no evidence for a God so he became an agnostic.[45] In an interview published in the Times newspaper in 2000 Sanger is quoted as saying: "My father was a committed Quaker and I was brought up as a Quaker, and for them truth is very important. I drifted away from those beliefs – one is obviously looking for truth, but one needs some evidence for it. Even if I wanted to believe in God I would find it very difficult. I would need to see proof."[46]

He declined the offer of a knighthood, as he did not wish to be addressed as "Sir". He is quoted as saying, "A knighthood makes you different, doesn't it, and I don't want to be different." In 1986 he accepted admission to the Order of Merit, which can have only 24 living members.[43][45][46]

In 2007 the British Biochemical Society was given a grant by the Wellcome Trust to catalogue and preserve the 35 laboratory notebooks in which Sanger recorded his research from 1944 to 1983. In reporting this matter, Science noted that Sanger, "the most self-effacing person you could hope to meet", was spending his time gardening at his Cambridgeshire home.[47]

Sanger died in his sleep at Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge on 19 November 2013.[43][48] As noted in his obituary, he had described himself as "just a chap who messed about in a lab",[49] and "academically not brilliant".[50]

Global policy[edit]

He was one of the signatories of the agreement to convene a convention for drafting a world constitution.[51][52] As a result, for the first time in human history, a World Constituent Assembly convened to draft and adopt a Constitution for the Federation of Earth.[53]

Selected publications[edit]

- Neuberger, A.; Sanger, F. (1942), "The nitrogen of the potato", Biochemical Journal, 36 (7–9): 662–671, doi:10.1042/bj0360662, PMC 1266851, PMID 16747571.

- Neuberger, A.; Sanger, F. (1944), "The metabolism of lysine", Biochemical Journal, 38 (1): 119–125, doi:10.1042/bj0380119, PMC 1258037, PMID 16747737.

- Sanger, F. (1945), "The free amino groups of insulin", Biochemical Journal, 39 (5): 507–515, doi:10.1042/bj0390507, PMC 1258275, PMID 16747948.

- Sanger, F. (1947), "Oxidation of insulin by performic acid", Nature, 160 (4061): 295–296, Bibcode:1947Natur.160..295S, doi:10.1038/160295b0, PMID 20344639, S2CID 4127677.

- Porter, R.R.; Sanger, F. (1948), "The free amino groups of haemoglobins", Biochemical Journal, 42 (2): 287–294, doi:10.1042/bj0420287, PMC 1258669, PMID 16748281.

- Sanger, F. (1949a), "Fractionation of oxidized insulin", Biochemical Journal, 44 (1): 126–128, doi:10.1042/bj0440126, PMC 1274818, PMID 16748471.

- Sanger, F. (1949b), "The terminal peptides of insulin", Biochemical Journal, 45 (5): 563–574, doi:10.1042/bj0450563, PMC 1275055, PMID 15396627.

- Sanger, F.; Tuppy, H. (1951a), "The amino-acid sequence in the phenylalanyl chain of insulin. 1. The identification of lower peptides from partial hydrolysates", Biochemical Journal, 49 (4): 463–481, doi:10.1042/bj0490463, PMC 1197535, PMID 14886310.

- Sanger, F.; Tuppy, H. (1951b), "The amino-acid sequence in the phenylalanyl chain of insulin. 2. The investigation of peptides from enzymic hydrolysates", Biochemical Journal, 49 (4): 481–490, doi:10.1042/bj0490481, PMC 1197536, PMID 14886311.

- Sanger, F.; Thompson, E.O.P. (1953a), "The amino-acid sequence in the glycyl chain of insulin. 1. The identification of lower peptides from partial hydrolysates", Biochemical Journal, 53 (3): 353–366, doi:10.1042/bj0530353, PMC 1198157, PMID 13032078.

- Sanger, F.; Thompson, E.O.P. (1953b), "The amino-acid sequence in the glycyl chain of insulin. 2. The investigation of peptides from enzymic hydrolysates", Biochemical Journal, 53 (3): 366–374, doi:10.1042/bj0530366, PMC 1198158, PMID 13032079.

- Sanger, F.; Thompson, E.O.P.; Kitai, R. (1955), "The amide groups of insulin", Biochemical Journal, 59 (3): 509–518, doi:10.1042/bj0590509, PMC 1216278, PMID 14363129.

- Ryle, A.P.; Sanger, F.; Smith, L.F.; Kitai, R. (1955), "The disulphide bonds of insulin", Biochemical Journal, 60 (4): 541–556, doi:10.1042/bj0600541, PMC 1216151, PMID 13249947.

- Brown, H.; Sanger, F.; Kitai, R. (1955), "The structure of pig and sheep insulins", Biochemical Journal, 60 (4): 556–565, doi:10.1042/bj0600556, PMC 1216152, PMID 13249948.

- Sanger, F. (1959), "Chemistry of Insulin: determination of the structure of insulin opens the way to greater understanding of life processes", Science, 129 (3359): 1340–1344, Bibcode:1959Sci...129.1340G, doi:10.1126/science.129.3359.1340, PMID 13658959.

- Milstein, C.; Sanger, F. (1961), "An amino acid sequence in the active centre of phosphoglucomutase", Biochemical Journal, 79 (3): 456–469, doi:10.1042/bj0790456, PMC 1205670, PMID 13771000.

- Marcker, K.; Sanger, F. (1964), "N-formyl-methionyl-S-RNA", Journal of Molecular Biology, 8 (6): 835–840, doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(64)80164-9, PMID 14187409.

- Sanger, F.; Brownlee, G.G.; Barrell, B.G. (1965), "A two-dimensional fractionation procedure for radioactive nucleotides", Journal of Molecular Biology, 13 (2): 373–398, doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(65)80104-8, PMID 5325727.

- Brownlee, G.G.; Sanger, F.; Barrell, B.G. (1967), "Nucleotide sequence of 5S-ribosomal RNA from Escherichia coli", Nature, 215 (5102): 735–736, Bibcode:1967Natur.215..735B, doi:10.1038/215735a0, PMID 4862513, S2CID 4270186.

- Brownlee, G.G.; Sanger, F. (1967), "Nucleotide sequences from the low molecular weight ribosomal RNA of Escherichia coli", Journal of Molecular Biology, 23 (3): 337–353, doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(67)80109-8, PMID 4291728.

- Brownlee, G.G.; Sanger, F.; Barrell, B.G. (1968), "The sequence of 5S ribosomal ribonucleic acid", Journal of Molecular Biology, 34 (3): 379–412, doi:10.1016/0022-2836(68)90168-X, PMID 4938553.

- Adams, J.M.; Jeppesen, P.G.; Sanger, F.; Barrell, B.G. (1969), "Nucleotide sequence from the coat protein cistron of R17 bacteriophage RNA", Nature, 223 (5210): 1009–1014, Bibcode:1969Natur.223.1009A, doi:10.1038/2231009a0, PMID 5811898, S2CID 4152602.

- Barrell, B.G.; Sanger, F. (1969), "The sequence of phenylalanine tRNA from E. coli", FEBS Letters, 3 (4): 275–278, doi:10.1016/0014-5793(69)80157-2, PMID 11947028, S2CID 34155866.

- Jeppesen, P.G.; Barrell, B.G.; Sanger, F.; Coulson, A.R. (1972), "Nucleotide sequences of two fragments from the coat-protein cistron of bacteriophage R17 ribonucleic acid", Biochemical Journal, 128 (5): 993–1006, doi:10.1042/bj1280993h, PMC 1173988, PMID 4566195.

- Sanger, F.; Donelson, J.E.; Coulson, A.R.; Kössel, H.; Fischer, D. (1973), "Use of DNA Polymerase I Primed by a Synthetic Oligonucleotide to Determine a Nucleotide Sequence in Phage f1 DNA", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 70 (4): 1209–1213, Bibcode:1973PNAS...70.1209S, doi:10.1073/pnas.70.4.1209, PMC 433459, PMID 4577794.

- Sanger, F.; Coulson, A.R. (1975), "A rapid method for determining sequences in DNA by primed synthesis with DNA polymerase", Journal of Molecular Biology, 94 (3): 441–448, doi:10.1016/0022-2836(75)90213-2, PMID 1100841.

- Sanger, F.; Nicklen, S.; Coulson, A.R. (1977), "DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 74 (12): 5463–5467, Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.5463S, doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463, PMC 431765, PMID 271968. According to the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) database, by October 2010 this paper had been cited over 64,000 times.

- Sanger, F.; Air, G.M.; Barrell, B.G.; Brown, N.L.; Coulson, A.R.; Fiddes, C.A.; Hutchinson, C.A.; Slocombe, P.M.; Smith, M. (1977), "Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage φX174 DNA", Nature, 265 (5596): 687–695, Bibcode:1977Natur.265..687S, doi:10.1038/265687a0, PMID 870828, S2CID 4206886.

- Sanger, F.; Coulson, A.R. (1978), "The use of thin acrylamide gels for DNA sequencing", FEBS Letters, 87 (1): 107–110, doi:10.1016/0014-5793(78)80145-8, PMID 631324, S2CID 1620755.

- Sanger, F.; Coulson, A.R.; Barrell, B.G.; Smith, A.J.; Roe, B.A. (1980), "Cloning in single-stranded bacteriophage as an aid to rapid DNA sequencing", Journal of Molecular Biology, 143 (2): 161–178, doi:10.1016/0022-2836(80)90196-5, PMID 6260957.

- Anderson, S.; Bankier, A.T.; Barrell, B.G.; De Bruijn, M.H.; Coulson, A.R.; Drouin, J.; Eperon, I.C.; Nierlich, D.P.; Roe, B.A.; Sanger, F.; Schreier, P.H.; Smith, A.J.; Staden, R.; Young, I.G. (1981), "Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome", Nature, 290 (5806): 457–465, Bibcode:1981Natur.290..457A, doi:10.1038/290457a0, PMID 7219534, S2CID 4355527.

- Anderson, S.; De Bruijn, M.H.; Coulson, A.R.; Eperon, I.C.; Sanger, F.; Young, I.G. (1982), "Complete sequence of bovine mitochondrial DNA. Conserved features of the mammalian mitochondrial genome", Journal of Molecular Biology, 156 (4): 683–717, doi:10.1016/0022-2836(82)90137-1, PMID 7120390.

- Sanger, F.; Coulson, A.R.; Hong, G.F.; Hill, D.F.; Petersen, G.B. (1982), "Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage λ DNA", Journal of Molecular Biology, 162 (4): 729–773, doi:10.1016/0022-2836(82)90546-0, PMID 6221115.

- Sanger, F. (1988), "Sequences, sequences, and sequences", Annual Review of Biochemistry, 57: 1–28, doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.000245, PMID 2460023.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Allen, A.K.; Muir, H.M. (2001). "Albert Neuberger. 15 April 1908 – 14 August 1996". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 47: 369–382. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2001.0021. JSTOR 770373. PMID 15124648. S2CID 72943723.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Brownlee, George G. (2015). "Frederick Sanger CBE CH OM. 13 August 1918 – 19 November 2013". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 61: 437–466. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2015.0013.

- ^ "Seven days: 22–28 November 2013". Nature. 503 (7477): 442–443. 2013. Bibcode:2013Natur.503..442.. doi:10.1038/503442a.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1958".

- ^ a b "Nobel Prize Facts". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1958: Frederick Sanger – biography". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "A Life of Research on the Sequences of Proteins and Nucleic Acids: Fred Sanger in conversation with George Brownlee". Biochemical Society, Edina – Film & Sound Online. 9 October 1992. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2013.. Subscription required. A 200 min interview divided into 44 segments. Notes give the content of each segment. [dead link]

- ^ Marks, Lara. "Sanger's early life: From the cradle to the laboratory". The path to DNA sequencing: The life and work of Fred Sanger. What is Biotechnology. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Jeffers, Joe S. (2017). Frederick Sanger Two-Time Nobel Laureate in Chemistry. Springer International. ISBN 978-3-319-54707-7.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1980".

- ^ Sanger, Frederick (1944). The metabolism of the amino acid lysine in the animal body (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge.

- ^ Neuberger & Sanger 1942; Neuberger & Sanger 1944

- ^ "Frederick Sanger, Ph.D. Biography and Interview". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ Chibnall, A. C. (1942). "Bakerian Lecture: Amino-Acid Analysis and the Structure of Proteins" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 131 (863): 136–160. Bibcode:1942RSPSB.131..136C. doi:10.1098/rspb.1942.0021. S2CID 85124201. Section on insulin starts on page 153.

- ^ Sanger & Tuppy 1951a; Sanger & Tuppy 1951b; Sanger & Thompson 1953a; Sanger & Thompson 1953b

- ^ Sanger, F. (1958), Nobel lecture: The chemistry of insulin (PDF), Nobelprize.org, retrieved 18 October 2010. Sanger's Nobel lecture was also published in Science: Sanger 1959

- ^ Marks, Lara. "Sequencing proteins: Insulin". The path to DNA sequencing: The life and work of Fred Sanger. What is Biotechnology. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Ryle et al. 1955.

- ^ Stretton, A.O. (2002). "The first sequence. Fred Sanger and insulin". Genetics. 162 (2): 527–532. doi:10.1093/genetics/162.2.527. PMC 1462286. PMID 12399368.

- ^ a b "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1958: Frederick Sanger". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- ^ a b Marks, Lara. "The path to sequencing nucleic acids". The path to DNA sequencing: The life and work of Fred Sanger. What is Biotechnology. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Marcker & Sanger 1964

- ^ Holley, R. W.; Apgar, J.; Everett, G. A.; Madison, J. T.; Marquisee, M.; Merrill, S. H.; Penswick, J. R.; Zamir, A. (1965). "Structure of a Ribonucleic Acid". Science. 147 (3664): 1462–1465. Bibcode:1965Sci...147.1462H. doi:10.1126/science.147.3664.1462. PMID 14263761. S2CID 40989800.

- ^ Brownlee, Sanger & Barrell 1967; Brownlee, Sanger & Barrell 1968

- ^ Sanger et al. 1973

- ^ Sanger & Coulson 1975

- ^ a b Sanger, F. (1980). "Nobel lecture: Determination of nucleotide sequences in DNA" (PDF). Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ Sanger et al. 1977

- ^ a b Sanger, Nicklen & Coulson 1977.

- ^ a b "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1980: Paul Berg, Walter Gilbert, Frederick Sanger". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- ^ Anderson et al. 1981

- ^ Sanger et al. 1982

- ^ Walker, John (2014). "Frederick Sanger (1918–2013) Double Nobel-prizewinning genomics pioneer". Nature. 505 (7481): 27. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...27W. doi:10.1038/505027a. PMID 24380948.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1972". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ Blackburn, E. H. (1974). Sequence studies on bacteriophage ØX174 DNA by transcription (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2009". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ "Schlessinger, David" (PDF). National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI, genome.gov). March 2018.

- ^ "The ABRF Award for Outstanding Contributions to Biomolecular Technologies". Association of Biomolecular Resource facilities. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "Summit Overview Photo".

Awards Council member and Nobel Prize laureate Dr. Charles H. Townes presenting the American Academy of Achievement's Golden Plate Award to British biochemist Dr. Frederick Sanger, recipient of two Nobel Prizes in Chemistry, at the 2000 Summit in Hampton Court.

- ^ "2016 Awardees". American Chemical Society, Division of the History of Chemistry. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Chemical Sciences. 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ "Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award" (PDF). American Chemical Society, Division of the History of Chemistry. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Chemical Sciences. 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ a b c "Frederick Sanger, OM". The Telegraph. 20 November 2013. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ a b c "Frederick Sanger". Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ a b Hargittai, István (April 1999). "Interview: Frederick Sanger". The Chemical Intelligencer. 4 (2). New York: Springer-Verlag: 6–11.. This interview, which took place on 16 September 1997, was republished in Hargittai, István (2002). "Chapter 5: Frederick Sanger". Candid science II: conversations with famous biomedical scientists. London: Imperial College Press. pp. 73–83. ISBN 978-1-86094-288-4.

- ^ a b Ahuja, Anjana (12 January 2000). "The double Nobel laureate who began the book of life". The Times. London. p. 40. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2010 – via warwick.ac.uk.

- ^ Bhattachjee, Yudhijit, ed. (2007). "Newsmakers: A Life in Science". Science. 317 (5840): 879. doi:10.1126/science.317.5840.879e. S2CID 220092058.

- ^ "Frederick Sanger: Nobel Prize winner dies at 95". BBC.co.uk. 20 November 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ "Frederick Sanger: Unassuming British biochemist whose pivotal and far-reaching discoveries made him one of a handful of double Nobel prizewinners". The Times. London. 21 November 2013. p. 63.

- ^ "Frederick Sanger's achievements cannot be overstated". The Conversation. 21 November 2013.

- ^ "Letters from Thane Read asking Helen Keller to sign the World Constitution for world peace. 1961". Helen Keller Archive. American Foundation for the Blind. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ "Letter from World Constitution Coordinating Committee to Helen, enclosing current materials". Helen Keller Archive. American Foundation for the Blind. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ "Preparing earth constitution | Global Strategies & Solutions | The Encyclopedia of World Problems". The Encyclopedia of World Problems | Union of International Associations (UIA). Retrieved 15 July 2023.

Bibliography[edit]

- Brownlee, George G. (2014). Fred Sanger, double Nobel laureate: a biography. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-08334-9. Chapters 4-6 contain the 1992 interview that the author conducted with Sanger.

- Finch, John (2008), A Nobel Fellow on every floor: a history of the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge: Medical Research Council, ISBN 978-1-84046-940-0.

- García-Sancho, Miguel (2010). "A new insight into Sanger's development of sequencing: from proteins to DNA, 1943–1977" (PDF). Journal of the History of Biology. 43 (2): 265–323. doi:10.1007/s10739-009-9184-1. hdl:20.500.11820/e4febe48-772a-4f47-a1c5-a5ca89505367. PMID 20665230. S2CID 1134280.

- Sanger, F.; Dowding, M. (1996), Selected Papers of Frederick Sanger: with commentaries, Singapore: World Scientific, ISBN 978-981-02-2430-1.

- Interviews with Nobel Prize–winning scientists: Dr Frederick Sanger, British Broadcasting Corporation, c. 1985. Interviewed by Lewis Wolpert. Duration 1 hour.

External links[edit]

- The Sanger Institute

- About the 1958 Nobel Prize

- About the 1980 Nobel Prize

- Fred Sanger 2001 Video Documentary by The Vega Science Trust

- Portraits of Frederick Sanger at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Frederick Sanger interviewed by Alan Macfarlane, 24 August 2007 (video), also available on Video on YouTube. Duration 57 minutes.

- Frederick Sanger archive collection – Wellcome Library finding aid for the digitised collection.

- Frederick Sanger on Nobelprize.org

- 1918 births

- 2013 deaths

- Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge

- Members of the European Molecular Biology Organization

- Fellows of King's College, Cambridge

- Academics of the University of Cambridge

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- English biochemists

- English agnostics

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences

- Members of the Order of Merit

- Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour

- Nobel laureates in Chemistry

- Nobel laureates with multiple Nobel awards

- British Nobel laureates

- People educated at Bryanston School

- People educated at Malvern College

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- English pacifists

- British conscientious objectors

- People educated at The Downs School, Herefordshire

- Royal Medal winners

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- English Nobel laureates

- People from Cotswold District

- Recipients of the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research

- Fellows of the Australian Academy of Science

- Foreign Fellows of the Indian National Science Academy

- World Constitutional Convention call signatories