Henry Polak

Henry Salomon Leon Polak (1882 — 31 January 1959) was a British-born lawyer, journalist and activist in South Africa who worked in collaboration with Mohandas Gandhi against racial discrimination. He served as an editor for the journal Indian Opinion and influenced by Theosophy, he believed in humanism and worked for the British Indian Association and several other causes.

Life and work[edit]

Polak was born in Dover, Kent in the Jewish family of Joseph and Adele Solomon Pool. He received admission to the London School of Economics but he was unable to afford studies there and after studying commerce for a while in Switzerland he attended evening classes at the Queen's Road Evening Institute in London. Here he met Millie Graham Downs, a Christian social activist. She introduced him to lectures organized at the Southgate Road Brotherhood Church by Reverend Bruce Wallace. He heard a talk by the Theosophist Annie Besant and readings on Tolstoy which influenced him. They also attended talks at the South Place Ethical Society. Polak moved to South Africa in 1903 to serve there in the family business leaving Millie behind.

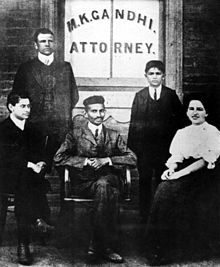

Polak first met Mohandas Gandhi in 1904 at Ziegler's vegetarian restaurant in Johannesburg, then being an editor of the Transvaal Critic. The two became close friends and Polak became the editor of the Indian Opinion from 1905 serving until 1916. Gandhi helped get Millie into South Africa and acted as best man at their wedding in South Africa on 30 December 1905. The magistrate at one point assumed that Henry was "coloured" due to his association with Gandhi and there were rules against "coloured" people marrying a white woman like Millie. Gandhi later persuaded Polak to study law, and was articled to Gandhi from 1905. He qualified in 1908 and handled Gandhi's legal practice and also became attorney of the Supreme Court of the Transvaal. When Gandhi visited London in 1906, Polak's father took Gandhi to the House of Commons to meet a liberal member of parliament. Polak and Gandhi introduced a range of writings to the audience of the Indian Opinion including ideas from Tolstoy, John Ruskin, Emerson, Mazzini, and Thoreau. Polak gifted Gandhi a copy of John Ruskin's Unto this last in 1904 which was to have a major influence. Polak published two books through G. A. Natesan on the situation of Indians in South Africa. Polak returned to England in 1916 and began to work with the British Committee of the Indian National Congress, editing the journal India. Extreme elements in the Indian National Congress like Bal Gangadhar Tilak disliked Polak's management of the India newsletter and he was forced to resign from the editorial position in 1919.[1] He was interested in inter-religious movements and took part in the World Congress of Religions at Geneva in 1937. Speaking in Madras in 1956, he drew parallels between the Theosophical movement and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights drafted in 1948. Polak had differences with Gandhi, and in later life they held more divergent views but continued to correspond with each other.[2][3][4]

References[edit]

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley A. (1961). Tilak and Gokhale: Revolution and Reform in the Making of Modern India. University of California Press. doi:10.1525/9780520323414-009. ISBN 978-0-520-32341-4.

- ^ Gandhi, Mohandas (2009). Parel, Anthony J. (ed.). M.K. Gandhi: Hind Swaraj and other writings (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511807268.031. ISBN 978-0-511-80726-8.

- ^ Haggis, Jane; Midgley, Clare; Allen, Margaret; Paisley, Fiona, eds. (2017). "Henry Polak: The Cosmopolitan Life of a Jewish Theosophist, Friend of India and Anti-racist Campaigner". Cosmopolitan Lives on the Cusp of Empire. Interfaith, Cross-Cultural and Transnational Networks, 1860–1950. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 37–60. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-52748-2_3.

- ^ Chatterjee, Margaret (1992). Gandhi and his Jewish friends. Macmillan. pp. 40–45.