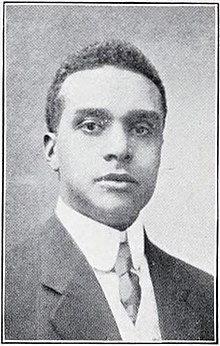

James A. Cobb

James A. Cobb | |

|---|---|

James A. Cobb | |

| Born | James Adlai Cobb January 29, 1876 |

| Died | October 14, 1958 (aged 82) |

| Occupation(s) | lawyer, judge |

James Adlai Cobb (January 29, 1876 – October 14, 1958) was an African-American lawyer, judge, and civil rights activist. He was a law professor at Howard University Law School, later becoming the school's vice-dean. As an attorney, he participated in court cases to help overturn discriminatory laws against African-Americans in the United States.[1]

Early life and education[edit]

Cobb was born on January 29, 1876, on a plantation in Louisiana, near the town of Arcadia.[2][3] Little is known about his parents, but his mother was thought to be Eleanor J. Pond, a white woman.[1] Cobb was orphaned as a young boy, and with no relatives to raise him, he was instead raised by family friends.[2]

As a teenager, Cobb worked as a post rider, delivering mail on horseback between Arcadia and Mount Lebanon. He delivered mail for a short period of time, until he was able to become a clerk at a general store. Eventually, he started a fruit and candy wagon. Once he saved up enough money from his work, he started attending private schools in the area.[2]

After leaving private school, Cobb attended Straight University in New Orleans. He then moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where he attended Fisk University's College Preparatory Department from around 1895 to 1897.[2][4] During the university's breaks, he worked at the Pullman Palace Car Company in their commissary department. Once he completed his studies as Fisk, he moved to Washington, D.C., to attend Howard University.[2] There, Cobb studied in the law department and graduated with a Bachelor of Laws degree in 1899 and a Master of Laws degree in 1900. He then attended the Howard University Teachers College, and graduated with a Bachelor of Pedagogy in 1902.[5]

Legal career[edit]

In 1901, Cobb was admitted to the bar in Washington, D.C. He began practicing law in the city, and mainly took on racial discrimination cases.[6]

In November 1907, Cobb was appointed as a special assistant attorney to the Attorney General for the District of Columbia by president Theodore Roosevelt and attorney general Charles Joseph Bonaparte.[7] He served in the position from 1907 to 1915, becoming the first black man to work as a special assistant in the Department of Justice.[8][2] During his time working, he prosecuted cases under the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act.[6] In 1915, Cobb resigned when the position was abolished and he restarted his private practice in D.C.[2]

Around June 1919, he was brought on as an attorney for the appeal of a man who shot two streetcar workers who attacked him after he sat in a whites only section of a streetcar.[9] The guilty verdict against Edgar C. Caldwell was appealed. Caldwell was a Black United States sergeant who was sentenced to hang by an all-white jury in Calhoun County, Alabama. The NAACP searched for a larger defense team for Caldwell before the case went to the Alabama Supreme Court. At the time, Cobb was the chairman of the legal committee for the NAACP's Washington, D.C., branch, and he was able to "briefly [raise] the spirits of Caldwell's defense team". However, the Alabama Supreme Court upheld the sentence against Caldwell.[10]

Cobb was a professor at Howard University Law School and in 1923, he became the vice-dean of the law school. He held the position of vice-dean until 1929.[8][11]

In 1926, Cobb was appointed Judge of the Municipal Court in Washington, D.C.,[12] becoming "the only African American on the municipal bench."[13][14] W. E. B. DuBois wrote to him about plans for Cobb to serve on a committee discussing The Crisis publication and its connections with the NAACP.[15] He also corresponded with Charles Young.[16]

Cobb died of leukemia in Washington, D.C., on October 14, 1958, at the age of 82.[17][18]

References[edit]

- ^ a b African-American Social Leaders and Activists. Facts On File. 2003. pp. 36–38. ISBN 978-0-8160-4840-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g "James A. Cobb Quits As A U. S. Prosecutor". Evening Star. 15 August 1915. p. 9. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "James A. Cobb". The Tampa Tribune. 17 October 1958. p. 2. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Catalogue of the Officers and Students of Fisk University. Press of folk-Keelin Print. Co. pp. 26, 250. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Howard university, Washington (1919). Alumni directory, 1870-1919. Washington, D.C., Howard university. pp. 55, 65. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ a b African American National Biography. Oxford University Press. 2013. ISBN 978-0-19-999036-8. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "Appointment of James A. Cobb". The New York Age. 21 November 1907. p. 4. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Colored Judges". The Crisis. 32 (4). The Crisis Publishing Company: 188–190. August 1926.

- ^ "July 30, 1920: Lynching of Sergeant Edgar Caldwell".

- ^ Mikkelsen, Vincent P. (2009). "Fighting for Sergeant Caldwell: The NAACP Campaign Against "Legal" Lynching After World War I". The Journal of African American History. 94 (4): 470. doi:10.1086/JAAHv94n4p464. ISSN 1548-1867. JSTOR 25653974. S2CID 141481751. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Lisio, Donald J. (1985). Hoover, Blacks, & lily-whites : a study of Southern strategies. University of North Carolina Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8078-1645-5. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "Black Rulers". The Crisis. 37 (4). The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc.: 132 April 1930. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "NMAH | Archives Center | Portraits of a City: The Scurlock Photographic Studio". amhistory.si.edu.

- ^ James A. Cobb Guest of Honor At Bar Dinner." Washington Post. 28 January 1934. p.13

- ^ "Letter from W. E. B. Du Bois to James A. Cobb, June 15, 1932". credo.library.umass.edu.

- ^ "ohiohistory.org / The African American Experience in Ohio, 1850-1920 / Charles Young Collection". dbs.ohiohistory.org.

- ^ "James A. Cobb Dies at Washington". The Tennessean. 16 October 1958. p. 39. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "The Week's Census". Jet. Vol. 14, no. 26. Johnson Publishing Company. 30 October 1958. p. 50. ISSN 0021-5996.

- 1876 births

- 1958 deaths

- 20th-century American lawyers

- 20th-century American judges

- 20th-century African-American lawyers

- African-American judges

- Straight University alumni

- Howard University School of Law faculty

- Howard University School of Law alumni

- People from Bienville Parish, Louisiana

- African-American academic administrators

- Deaths from leukemia in Washington, D.C.

- Judges of the Superior Court of the District of Columbia