João Manuel de Lima e Silva

João Manuel de Lima e Silva | |

|---|---|

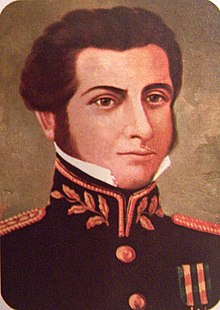

Lima e Silva, c. 1830 | |

| Born | 2 March 1805 Rio de Janeiro, State of Brazil |

| Died | 29 August 1837 (aged 32) São Borja, Rio Grande do Sul, Empire of Brazil |

| Allegiance | |

| Battles/wars | Brazilian War of Independence Cisplatine War Ragamuffin War |

| Spouse(s) |

Maria Joaquina de Almeida Corte Real

(m. 1828) |

| Relations | Francisco de Lima e Silva (brother) Luís Alves de Lima e Silva (nephew) |

João Manuel de Lima e Silva (2 March 1805 – 29 August 1837) was a Brazilian military officer and revolutionary leader, being the first general of the Riograndense Republic.

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

The son of José Joaquim de Lima e Silva and Joana Maria da Fonseca Costa, João Manuel was born in Rio de Janeiro on 2 March 1805, being from a traditional military family. His father was a Portuguese marshal who arrived in Brazil in 1783 as captain of the Braganza Regiment. He was the brother of Francisco de Lima e Silva, José Joaquim de Lima e Silva and Manuel da Fonseca de Lima e Silva; he was also the uncle of Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, later Duke of Caxias, despite being younger than his nephew. João Manuel joined the Royal Military Academy in Rio de Janeiro at the age of fifteen with the rank of alferes. From 1820 to 1821 he took the first year of the math course and the fifth year of the military course in 1822, graduating from the academy that same year with the rank of infantry lieutenant of the 1st Battalion of Fusiliers.[1][2][3]

Brazilian War of Independence[edit]

After graduating, in 1822, João Manuel actively took part in the Brazilian War of Independence in Bahia as part of the so-called Emperor's Battalion alongside his nephew, Luís Alves de Lima e Silva. The commander and subcommander of the battalion were his brothers José Joaquim de Lima e Silva, later Viscount of Magé, and Manuel da Fonseca de Lima e Silva, the Baron of Suruí, respectively. José Joaquim took part in the battle of Pirajá and also commanded the Brazilian Army in Bahia in the absence of general Pierre Labatut.[1][2]

Cisplatine War[edit]

In 1825, João Manuel volunteered to fight in the Cisplatine War against the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata in southern Brazil. Upon his arrival in Rio Grande do Sul, he was given command of the 1st Company of the 3rd Battalion of Caçadores of Rio de Janeiro. This unit was part of the 1st Infantry Brigade, which in turn was part of the 1st Infantry Division, whose commander was general Sebastião Barreto Pereira Pinto. On 20 February 1827, João Manuel took part in the battle of Ituzaingó as part of the 3rd Battalion of Caçadores. He was later promoted to major and even got to command a brigade and a division.[4]

With the end of the war, João Manuel, now major, was sent to Porto Alegre and given interim command of the 28th Battalion of Caçadores, which had been transferred to Porto Alegre in 1828 following a rebellion in Rio de Janeiro that same year. This battalion consisted of German mercenaries and was part of the Foreigner Corps. It had been hired to fight in the Cisplatine War. João Manuel was tasked with disciplining the battalion and, if it were no longer needed, dissolve it.[5]

João Manuel was later given interim command of the 8th Battalion of Caçadores and married Maria Joaquina de Almeida Corte Real on 24 April 1828. Maria Joaquina was the sister of Afonso José Corte Real, who later also joined the rebel side on the Ragamuffin War and took part in the capture of Porto Alegre on 20 September 1835.[2][6] João Manuel also supported the political events led by his brother Francisco de Lima e Silva that culminated in the abdication of emperor Pedro I of Brazil on 7 April 1831.[6]

Ragamuffin War[edit]

Political conspirations[edit]

According to Cláudio Moreira Bento, João Manuel might have been influenced by his wife's family and personal disappointments, and also the events taking place in the neighboring Platine states, the United Provinces and Uruguay, which slowly turned him into a defender of liberalism and republicanism in contrast to the monarchical regime of the Empire of Brazil.[6] After Pedro I's abdication, João Manuel bought a typography called Fonseca e Cia, which he installed in his house and used to print the journal O Continentino, issued every two weeks. His house was also the seat of a political association called Sociedade Continentino, which congregated republican sympathizers and opposed another association named Sociedade Militar; the latter defended the return of emperor Pedro I to the Brazilian throne.[6][7] Sociedade Continentino had a Masonic character and operated in secret; some of its members included Italian Tito Lívio Zambecari, José Pinheiro de Ulchoa Cintra, from Minas Gerais, Manuel Ruedas, from Uruguay, and José Mariano de Matos, who was a close friend of João Manuel and one of his colleagues at the Royal Academy, sharing his republican and federalist ideas.[8]

In November 1833, João Manuel became the subject of a military inquiry and was summoned to the Court in Rio de Janeiro, together with colonel Bento Gonçalves, to defend himself before the Minister of War amidst accusations of conspiring with the 28th Battalion of Caçadores and German colonists from São Leopoldo to separate Rio Grande do Sul from the Empire.[5] The accusations were made by José Mariani, then president of the province, and general Sebastião Barreto, the provincial Commander of Arms.[2][6] The inquiry was inconclusive and João Manuel was acquitted, but it resulted in the arrest of major Otto Heise, two captains and some civilians from São Leopoldo, all German immigrants, who were later released.[9] A large number of the military officers in Porto Alegre held republican views, which prompted Barreto to allocate these officers to Brazil's frontiers with the neighboring countries; this included João Manuel, who was sent to São Borja with the 8th Battalion of Caçadores on 22 March 1834.[6]

Outbreak of the war and initial actions[edit]

João Manuel became the subject of suspicion by the local authorities, especially by José Egídio Gordilho de Barbuda, the 2nd Viscount of Camamu. Barbuda, an ultramonarchist, attacked João Manuel on a newspaper. In response, Manuel filed a lawsuit against Barbuda, who was then condemned on 10 July 1834 for his personal attacks against João Manuel. However, Barbuda's sentence was alleviated by the provincial president, who used a series of tricks to lessen the penalty, damaging his image in the process. Barbuda was sent to prison and tried to organize a mutiny against colonel Silvano José Monteiro de Araújo e Paula, a commander of the National Guard and the prison's officer. The mutiny failed without any major immediate consequences, but the events had a negative repercussion across the province, leading to the further radicalization of both sides.[8]

The transfer of army personnel to remote areas promoted earlier by Sebastião Barreto left the capital Porto Alegre defended only by a diminished force consisting of the local police and National Guard units. The rebels took advantage of this and initiated the rebellion on 20 September 1835 by capturing Porto Alegre. In the initial rebel plan, João Manuel was tasked with securing the rebel position in São Borja and reinforcing colonel Bento Manuel Ribeiro with forces from Cruz Alta. Once Porto Alegre had been taken by the rebels, João Manuel moved to Alegrete with the 8th Battalion of Caçadores; from there he was called to help Marciano José Pereira Ribeiro as advisor to the office of provincial Commander of Arms. The rebels deposed Antônio Rodrigues Fernandes Braga, the provincial president, and sworn Marciano José as the new president of the province. João Manuel temporarily assumed the office of Commander of Arms on 4 December 1835 and definitely on 17 February 1836, after Bento Manuel Ribeiro defected to the Imperial side.[2][10]

After the new president of the province took office, João Manuel moved to São José do Norte with Domingos José de Almeida and Domingos Gonçalves Chaves, all of which represented the provincial assembly, in order to hold a conference with Marciano Ribeiro. Later, João Manuel moved to Caçapava do Sul in order to prepare to attack the coastal city of Rio Grande, which had strategic importance due to its port. João Manuel joined his troops with colonel Souza Neto and Domingos Crescêncio de Carvalho in order to carry out the attack; however, the Imperial government sent brigadier Antônio Elzeário de Miranda e Brito to reinforce the city with five hundred infantry and artillerymen, six cannons and three warships. The reinforcements' arrival prevented the rebels from capturing Rio Grande. The city became a naval base for the navigation of the province's interior rivers, which were dominated by the Imperial Navy under the command of John Pascoe Grenfell.[11]

Assassination[edit]

After leaving a ball in São Borja, on 29 August 1837, he was ambushed by the indigenous Roque Faustino and assassinated helpless, left naked and unburied.[12]

In 1840, after the Battle of Caçapava, by orders of general Manuel Jorge Rodrigues, executed by Bonifácio Izaías Calderón and Manuel dos Santos Loureiro, his grave was desecrated and his remains were spread across the fields.[12]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Bento 1992, pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b c d e Hartmann 2002, p. 85.

- ^ Doria 1918, p. 378.

- ^ Bento 1992, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Hartmann 2002, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f Bento 1992, p. 44.

- ^ Flores 1999.

- ^ a b Bento 1992, p. 45.

- ^ Hartmann 2002, pp. 41, 64.

- ^ Bento 1992, p. 46.

- ^ Bento 1992, p. 47.

- ^ a b Bento 1992, pp. 67–68.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bento, Cláudio Moreira (1992). O Exército Farrapo e os seus Chefes (PDF) (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército.

- Doria, Luiz Gastão de Escragnolle (1918). Publicações do Archivo Nacional sob a direção de Luiz Gastão de Escragnolle Doria (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Archivo Nacional.

- Flores, Hilda Agnes Hubner (1999). Alemães na Guerra dos Farrapos (in Portuguese). Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS.

- Hartmann, Ivar (2002). Aspectos da Guerra dos Farrapos (PDF) (in Portuguese). Novo Hamburgo: Editora Feevale.