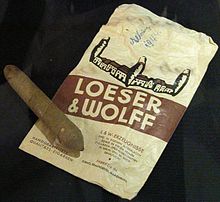

Loeser & Wolff

Loeser & Wolff was a large German tobacco goods factory and trade in Berlin that was Aryanized by the Nazis because its owners were Jewish. It manufactured, imported and distributed cigars in particular. It was at times the largest cigar factory in Europe and a Jewish company until its Aryanization in 1937.

History and significance[edit]

Beginnings[edit]

On July 1, 1865, Bernhard Loeser (born April 17, 1835, in Quedlinburg) and Carl Wolff (born 1825) founded a tobacconist's shop; it is recorded as being located at Alexanderstrasse 3 in 1866. The headquarters had been located at Alexanderstraße 1 since 1867. Wolff was responsible for the Berlin retail stores, Loeser for wholesale beyond that.[1]

Expansion beginning[edit]

In order to meet the growing demand and to be closer to the important sales region in the east of what was then Prussia, Loeser acquired shares in the cigar factory Jean Kohlweck & Co. in Elbing (West Prussia, today Elbląg in Poland) on January 20, 1874, whereupon it changed its name to Kohlweck & Loeser. In 1878 he took it over completely and changed its name to Zigarrenfabrik Loeser & Wolff. When he joined the company in 1874, 26,700 cigars were produced by hand from imported raw tobaccos with around 40 exclusively female employees. Due to rapidly growing demand, the factory was expanded in the same year, as well as in 1880, 1881 and 1882.[2][1]

Model company[edit]

The largest company in Elblag was the Schichau-Werke shipyard and machine factory. The cigar factory's women's jobs offered families an important additional income with far above-average social benefits.[3][1]

The share of wholesale trade and exports to Europe, Africa, Asia and Japan quickly exceeded the importance of the retail business. In 1881, Loeser presented the company at the Melbourne International Exhibition in Melbourne/Australia and received the 1st prize there. At exhibitions in Königsberg, Bromberg and Berlin, the high quality of the cigars was awarded.[1]

Further expansion[edit]

In 1885, Loeser had a second factory built in the nearby district town of Braunsberg (East Prussia, now Braniewo/Poland), and on December 1, 1911, another production facility went into operation in Marienburg (West Prussia, now Malbork/Poland), and in 1911, another went into operation in Prussian Stargard (West Prussia, now Starogard Gdański/Poland). All the factories were managed from Elblag, where the largest factory was located, by Director Franz Wilhelm Pamperin.[4] Pamperin was himself a son of a small tobacco factory owner in Elbing. In 1896, a small production plant in Bremen was added. In the same year, the company was the supplier of tobacco products at the Berlin Trade Exhibition. On the southern shore of the Neuer See, Loeser and Wolff had its own pavilion with a tobacco museum and exhibition. Here there were demonstrations on cigar box production and cigar making. For the production of a cigarette, LuW commissioned the Manoli cigarette factory in Berlin, which produced an exhibition cigarette under the emblem of the hammer fist, which was distributed through LuW on the premises.

In 1890, on the occasion of the company's 25th anniversary, Kaiser Wilhelm II appointed Loeser an honorary member of the National Veterans' Association. On January 29, 1895, Loeser received the honorary title of Königlich-preußischer Kommerzienrat. At the end of the 19th century, Loeser & Wolff was awarded the Royal Prussian State Medal in Gold several times. In 1899, to mark the 25th anniversary of the factory in Elbling, a street on the company's property was renamed Loeserstrasse.

Loeser died in Berlin on May 2, 1901. He is buried in the Jewish Cemetery Berlin-Weißensee. In the same year, there were already 66 stores in Berlin, 2,000 predominantly female employees worked in the Elbing and Braunsberg factories, and around 100 million cigars were produced.

On November 13, 1902, co-founder Carl Wolff also died. His widow Cäcilie and Loeser's son-in-law, the senior government and building councilor Alfred Sommerguth, continued to run the company, which subsequently reached the peak of its prosperity.[5]

Growth[edit]

In 1907, almost 3900 people were employed, 3280 of them in Elbing. In 1914, a company advertisement stated 120 sales outlets. In the fiscal year 1915–16, i.e. during the First World War, shortly before the establishment of the German Tobacco Trading Company and the war-related compulsory state management of tobacco, a total of 194,500,000 cigars were produced. The highest weekly production was 4,000,000. In 1916, Loeser & Wolff employed almost 5000 people, 3740 of them in Elbing alone.

After the end of the First World War, the branch plant in Prussian Stargard became Polish. In 1920, the two heirs united the remaining and hitherto legally independent sub-operations into a limited liability company. In the following year, a smoking tobacco factory was installed. The company briefly stopped production for months in 1922–23, but recovered after some time. At the end of the 1920s, the daughter Lucia Sommerguth-Loeser took over the management.

From 1928 to 1930, it had a new administrative headquarters building designed by the architect Albert Biebendt on a 1,445 m2 plot of land at the corner of Schöneberger Ufer 47 and Potsdamer Strasse 58 (Tiergarten district, Mitte borough) in the style of the early New Objectivity, which was one of the first high-rise buildings in Berlin.[6]

The "Loeser & Wolff" building, which juts out over the Landwehr Canal like the prow of a ship, was nicknamed the "Loeser Castle" by the Berlin vernacular at the time; today it is neutrally called the "Loeser & Wolff House".[7]

Nazi persecution[edit]

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Loeser & Wolff was persecuted as a Jewish company. Loeser & Wolff was aryanized, that is transferred to a non-Jewish owner.[8][9]

Lucia Sommerguth-Loeser died in 1937.[10] Its Berlin director Walter E. Beyer took over the company on April 1, 1937, as part of the Aryanization process.[11] A short UfA advertising film of the "Walter E. Beyer Cigar Factories" with Rudolf Platte and Eduard Wenck has been preserved from 1942.[12]

Postwar[edit]

Until 1952, the company was owned under Beyer's name, after which 80% passed into the hands of the Lucia Loeser Foundation. Beyer, however, remained managing director until December 31, 1963. The Elbing branch no longer existed in 1952 at the latest; after 1945, the "Truso" textile factory (which also no longer exists today) was established there. The Iron Curtain separated the other plants from the supply of the distribution center in Berlin.

In 1964, the architects Hans Scharoun and Edgar Wisniewski moved into an office on the top floor (attic) of the Berlin "Loeser & Wolff" building, which was built in the 1920s and listed as a historic monument in 1955, after they had won the "Capital City Berlin" competition in 1958 to build the Kulturforum (with the Philharmonic Hall, State Library and Chamber Music Hall), which was not far away. The office existed there for forty years until its renovation. In 1972, one of the first Greek restaurants in Berlin opened on the first floor; it no longer exists. A physiotherapy practice has taken up residence here

On June 30, 1983, the company "Loeser & Wolff" was dissolved.

Around the year 2000, "Polis AG", a real estate holding company of Bank Delbrück, acquired the "Loeser & Wolff" building. In cooperation with the project development company Beos, it was completely renovated and converted from 2002 to 2004 at a cost of 22.5 million euros. According to the plans of the architectural firm Gerkan, Marg and Partner, it was given two additional glazed gable floors. The initially controversial addition was based on rediscovered original plans by Scharoun, who envisioned a three-story staggered glass addition. Until 2017, the new floors housed the "40 Seconds Lounge," a party club, while the 8th floor is now home to the Golvet restaurant. The other floors are used, among others, by Deutsche Entertainment AG, the Berlin regional association of company health insurance funds, the company DfV (services for insurance carriers), an art gallery, investment consultants, architects' and lawyers' offices.

Mentions in literature[edit]

Alfred Döblin mentions Loeser & Wolff in his Berlin metropolitan novel Berlin Alexanderplatz - The Story of Franz Biberkopf.[13]

The title of Walter Kempowski's novel Tadellöser & Wolff is derived from the company name: Kempowski's father, who often bought from Loeser & Wolff, used this phrase when he wanted to praise something.

"Tadellöser & Wolff? What does that actually mean?" Well, good things, nothing more. That's just how people talk in the city. "Gutmannsdörfer" is also one of those phrases. If you think something is good, then you just say "Gutmannsdörfer". Or "Schlechtmannsdörfer", or "Miesnitz & Jenssen".

- from: Tadellöser & Wolff. S. 300

Literature[edit]

- Loeser und Wolff. Aus der Geschichte einer Weltfirma. Einzelschriften der Historischen Kommission für Ost- und Westpreussische Landesforschung. Elwert. 2001. pp. 405–423. ISBN 3-7708-1177-1.

- Peter Schubert: Haus Loeser & Wolff. In: Welt am Sonntag, 19. Dezember 2004.

External links[edit]

- Hans-Jürgen Schuch: Loeser, Bernhard. In: Ostdeutsche Biografie (Kulturportal West-Ost) – mit weiterer Literatur

- Westpreußische Unternehmer, u. a. zur Geschichte von Loeser & Wolff, von Christa Mühleisen, mit historischen Ansichten und weiterer Literatur

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Schuch, Hans-Jürgen (2001). Loeser & Wolff aus der Geschichte einer Weltfirma. OCLC 1075178961.

- ^ "Manoli-Sammlung Rainer Immensack" (in German). Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- ^ Abbott, Edith (1907). "Employment of Women in Industries: Cigar-Making: Its History and Present Tendencies" (PDF). Journal of Political Economy. 15 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1086/251279. JSTOR 1817494. S2CID 153565647. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

- ^ "Loeser, Bernhard – Kulturstiftung" (in German). Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ^ "A Spectacular Pissarro that Escaped Theft by the Nazis". sothebys.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-28.

- ^ "Loeser & Wolff Building (Berlin-Tiergarten, 1929)". Structurae. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

- ^ Kathrin., Chod (2001). Berliner Bezirkslexikon Mitte. Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein. OCLC 314195794.

- ^ "Two Big Jewish Firms "Aryanized" by Nazis". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 1937-05-03. Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- ^ "History | Virtual Shtetl". sztetl.org.pl. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

In Elbląg, anti-Jewish persecutions was epitomised by the act of seizing the D. Loewenthal Department Store, one of the finest establishments of that sort, from its Jewish owners – Alfred, Heinrich, and Kurt Loewenthal, and by the "Aryanisation" of the Loesser & Wolff Cigar Factory, which was renamed to Walter E. Beyer. The year 1934 saw the disappearance of Loessera Street (Loessrstraße). The authorities called for a boycott of Jewish companies, stores run by Jews were vandalised. All Jewish attorneys were laid off in April 1933[1.26]. During the so-called Kristallnacht, on the night of 9/10 November 1938, the fire department set "controlled" (!) fire to the synagogue. Jewish shops were plundered and all Jewish men were arrested

- ^ "Loeser und Wolff Tabakwarenfabrik". CIGABOX.DE (in German). Retrieved 2023-11-13.

Die Tochter Lucia Sommerguth-Loeser übernahm 1929 die Leitung der Firma. Sie starb 1937. 1935 fiel das Unternehmen der Arisierung zum Opfer. Der langjährige Mitarbeiter Walter E. Beyer übernahm die Geschäfte. Die Firma wurde 1940 in Walter E. Beyer Zigarrenfabriken umbenannt und firmierte bis 1952 unter diesem Namen. 1983 wurde die Firma „Loeser & Wolff" aufgelöst.

- ^ "AUS ERSTER QUELLE. R: ? [DE, 1942]". 2007-02-19. Archived from the original on 2007-02-19. Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- ^ Loeser & Wolff has become Aryanized, retrieved 2022-01-28

- ^ Hake, Sabine (1994). "Urban Paranoia in Alfred Döblin's Berlin Alexanderplatz". The German Quarterly. 67 (3): 347–368. doi:10.2307/408630. ISSN 0016-8831. JSTOR 408630.