On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life

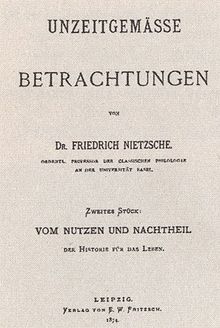

On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life (German: Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen. Zweites Stück: Vom Nutzen und Nachtheil der Historie für das Leben) is a work by Friedrich Nietzsche published in 1874 and the second of his four Untimely Meditations. The treatise is considered an important work from Nietzsche's early creative period (see Friedrich Nietzsche bibliography). In it, he criticizes his academic contemporaries who, in his opinion, either overestimate or misjudge the importance of history. This work also anticipates Nietzsche's later themes and has received comparatively great attention.

Overview[edit]

Nietzsche's Untimely Meditations are primarily writings of cultural criticism and are not as thematically broad as Nietzsche's later, consistently philosophical works. However, he approaches the subject from different angles. Thus, when he deals with the possibilities of historical science, he addresses the topics of philosophy of history and philosophy of science. On the other hand, by relating history to (human) life, he also engages in a kind of anthropology. The text is written within the framework of these four subjects.

Several interpreters have pointed out that Nietzsche's term Historie in particular is not clearly defined in the text, but fluctuates between the meanings of 'history' (res gestae, the actual events), 'historiography' (historia rerum gestarum, the narration of events) and 'historical science'. This should be borne in mind when Nietzsche's terminology is used in the following.

After an introduction in which Nietzsche shares his personal motivation for writing the book, the first chapter examines the origin of "history". The animal lives only in the present - with a modest degree of happiness - and is therefore unhistorical. Humans, in contrast, have the ability to remember. This enables them to create culture. On the other hand, individual memories and collective records are always a burden. Once this burden becomes too great, the capacity of a person or people to survive is inhibited. In Nietzsche's eyes, history is therefore both a necessity and a threat.

The second and third chapters deal with three functions that history has. "Monumental" history drives people to great deeds, "antiquarian" history preserves their collective identity, and "critical history" eliminates harmful memories. However, all three functions could turn pathological, which is why they must be in balance with one another. This categorization by Nietzsche is probably the best-known content of the text and has been taken up and interpreted in many ways.

In chapters 4–8, Nietzsche describes how an over-saturation with history can be hostile to life and culture. Nietzsche's attacks are always aimed at his contemporaries, especially in Germany, but also claim a general philosophical background. He diagnoses five "diseases" of the present, which are said to be caused by the incorrect use of history: firstly, a disturbed German identity, secondly, a lack of a sense of justice, thirdly, a lack of maturity, fourthly, a view of oneself as an epigone and fifthly, a pathological cynicism. The ninth chapter also belongs thematically to Nietzsche's criticism of the present. It includes a critique of Eduard von Hartmann's work Philosophy of the Unconscious, which was successful at the time.

In the tenth chapter, Nietzsche finally presents the cure for what he sees as a sick present: The powers of the unhistorical and "super-historical" - he mentions art and religion - would have to be promoted in order to finally arrive at a "true education" instead of one-sided, scientific "erudition".

Reception[edit]

Andreas-Salomé[edit]

Lou Andreas-Salomé already attached great importance to the second Untimely Meditation.[1] According to Salomé, history in this writing also stands for the life of thought in general, and according to Nietzsche, this must serve the life of instinct. In this demand and the remarks on "plastic power" (HL, chapter 1), she recognizes an early form of what Nietzsche later called the "Dionysian". When Nietzsche describes the opposite state, in which a multitude of foreign influences and thoughts turn the person who is unable to assimilate and organize them into a "passive arena of confused struggles",[2] he anticipates his later concept of decadence. Salomé also investigated Nietzsche's own psychological statement that he was aware of the danger of history because he had observed it in himself. According to her, Nietzsche often projected his self-observations onto his environment, and thus history appeared to him as a danger to the entire age. This is why the writing has a contradictory double character, as Nietzsche on the one hand opposes the paralyzing effect of intellectual activity, as he observed it in his contemporaries, but on the other hand also opposes an excess of conflicting influences and feelings, as he found them in himself: "It is a difference like between stupor of the soul and madness of the soul."[3]

According to Salomé, the three types of history could, in retrospect, be assigned to Nietzsche's creative periods: the antiquarian to the philologist, the monumental to the disciple of Schopenhauer and Wagner, and the critical to the positivist, free-spirited period. In his last creative period, Nietzsche then attempted to unite and overcome these approaches. In doing so, he reverted, albeit in a modified form, to the strong natures he had already called for here, whose unhistorical strength is shown in how much history they can tolerate. What in Nietzsche's early cult of genius was the historical-unhistorical, "untimely" human being, who "builds the future through the past, superior to the present".[4]

Vattimo[edit]

Gianni Vattimo considers the work to be "particularly fascinating, although it [...] raises and poses more problems and questions than it solves and answers."[5] Vattimo believes that the second Untimely can "only with difficulty be understood as the end point of a development or as the preparation of later theses - such as the doctrine of the Eternal Return".[6]

Vattimo considers the criticism of "historicism" as one of the predominant intellectual currents of the 19th century to be particularly important. This criticism was directed less against Hegelian metaphysics itself than against its social consequences, the one-sided focus on historiography in education and upbringing. Vattimo particularly emphasizes Nietzsche's criticism of the feeling of epigonism. The people of the late 19th century actually felt that the teachings of Hegel, Darwin and positivism - possibly in a popularized form - were the end and culmination of "world history". With his description of the weakened personality, which has an excess of knowledge but no inner connection to it and constantly needs new stimulants, Nietzsche foresaw "a characteristic sign of mass culture [...] in the 20th century".[7] However, Vattimo criticizes Nietzsche's suggestion of a recourse to "'super-historical' powers", which is not sufficiently thought through: "[A]fter the clarity and unambiguity of the destructive provisions, the constructive aspects of the writing [...] appear at best as a collection of demands that remain largely undefined."[8]

Vattimo dated the beginning of philosophical postmodernism between the writing of On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life and Human, All Too Human (1878):[9] Nietzsche had clearly seen that "overcoming" - a term widely discussed by Vattimo, which he contrasts with the term "transformation" borrowed from Heidegger - was itself a typically "modern" act and thus not applicable to modernity itself. In his early writings, he attempted the unconvincing recourse to super-historical and eternizing powers; in his subsequent period, Nietzsche decided on a dissolution of modernity through the "radicalization of the very tendencies that constitute this modernity itself".[10]

Other authors[edit]

Nietzsche's text On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life is by far the most influential of the four Untimely Meditations. This text has had a huge impact that extends far beyond philosophy: to this day, it plays an important role in controversial discourses between philosophers, historians and cultural scientists.[11]

References[edit]

- ^ Andreas-Salomé, Lou (1894). Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken (in German). Frankfurt: Insel Verlag (published 2000). p. 92. ISBN 3458342923.

- ^ Andreas-Salomé. Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken. p. 93.

- ^ Andreas-Salomé. Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken. p. 95.

- ^ Andreas-Salomé. Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken. p. 99.

- ^ Vattimo, Gianni (1992). Nietzsche: eine Einführung (in German). Stuttgart: Metzler. p. 22. ISBN 3476102688.

- ^ Vattimo. Nietzsche: eine Einführung. p. 22.

- ^ Vattimo. Nietzsche: eine Einführung. p. 25.

- ^ Vattimo. Nietzsche: eine Einführung. p. 26.

- ^ Vattimo, Gianni (1990). "Nihilismus und Postmoderne in der Philosophie". Das Ende der Moderne (in German). Stuttgart: Reclam. p. 178. ISBN 3150086248.

- ^ Vattimo. Das Ende der Moderne. p. 180.

- ^ Neymeyr, Barbara (2020). Kommentar zu Nietzsches Unzeitgemässen Betrachtungen. I. David Strauss der Bekenner und der Schriftsteller. II. Vom Nutzen und Nachtheil der Historie für das Leben (= Historischer und kritischer Kommentar zu Friedrich Nietzsches Werken (in German). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 305–386.

Bibliography[edit]

Nietzsche-Ausgabe[edit]

- In the Kritische Gesamtausgabe (KGW) published by Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari, On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life (Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben) can be found in: Section III, Volume 1 (together with Geburt der Tragödie, the first and the third Unzeitgemäßen Betrachtungen), ISBN 3-11-004227-4.(In German)

- The Kritische Studienausgabe (KSA) provides the same text in volume 1 (together with the Geburt der Tragödie, all other Unzeitgemäßen Betrachtungen, Nachgelassene Basler Schriften and with an afterword by Giorgio Colli). The volume KSA 1 is also published as a single volume under ISBN 3-423-30151-1. (In German)

- In 1995, Ernst Klett Schulbuchverlag published an edition of the text with materials and interpretations, including texts by Wilhelm Weischedel, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Jacob Burckhardt and others, edited by Joachim Vahland, ISBN 3-12-692040-3. (In German)

- In addition to individual editions of the work published by Reclam ISBN 3-15-007134-8 and Diogenes ISBN 3-257-21196-1, there are editions of all Unzeitgemäße Betrachtungen: there is an edition published by Goldmann Verlag with annotations by Peter Pütz, ISBN 3-442-07638-2 and another one published by Insel Verlag with an afterword by Ralph-Rainer Wuthenow, ISBN 3-458-32209-4. (In German)

Secondary sources[edit]

All major works on Nietzsche also deal with the second Untimely Meditation. Detailed bibliographies can be found in the works by Neymeyr, Salaquarda and Sommer listed here.

- Geijsen, Jacobus (1997). Geschichte und Gerechtigkeit: Grundzüge einer Philosophie der Mitte im Frühwerk Nietzsches (in German). Berlin/New York: de Gruyter. ISBN 3110156474.

- Haeuptner, Gerhard (1936). Die Geschichtsansicht des jungen Nietzsche: Versuch einer immanenten Kritik der zweiten unzeitgemäßen Betrachtung (in German). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Heidegger, Martin (2003). Zur Auslegung von Nietzsches II. Unzeitgemässer Betrachtung: "Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben" (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Klostermann. ISBN 3465032861.

- Neymeyr, Barbara (2020). Kommentar zu Nietzsches Unzeitgemässen Betrachtungen. I. David Strauss der Bekenner und der Schriftsteller. II. Vom Nutzen und Nachtheil der Historie für das Leben (= Historischer und kritischer Kommentar zu Friedrich Nietzsches Werken.) (in German). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. ISBN 978311028682-3.

- Salaquarda, Jörg (1984). "Studien zur Zweiten Unzeitgemäßen Betrachtung". Nietzsche-Studien. Internationales Jahrbuch für die Nietzsche-Forschung. 13: 1–45. ISSN 0342-1422.

- Schröter, Harmut (1982). Historische Theorie und geschichtliches Handeln – zur Wissenschaftskritik Nietzsches (in German). Mittenwald: Mäander. ISBN 3882191082.

- Sommer, Andreas (1997). Der Geist der Historie und das Ende des Christentums. Zur Waffengenossenschaft von Friedrich Nietzsche und Franz Overbeck (in German). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. ISBN 3050031123.

- Hayden White, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in 19th-century Europe, 1973 ISBN 0-8018-1761-7

External links[edit]

On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for life (complete text in German):

- in the digital Kritische Gesamtausgabe

- at Project Gutenberg