Pizza

A pizza divided into eight slices | |

| Type | Flatbread |

|---|---|

| Course | Lunch or dinner |

| Place of origin | Italy |

| Region or state | Naples, Campania |

| Serving temperature | Hot or warm |

| Main ingredients | Dough, sauce (usually tomato sauce), cheese (typically mozzarella, dairy or vegan) |

| Variations | Calzone, panzerotto |

| Part of a series on |

| Pizza |

|---|

Pizza (/ˈpiːtsə/ PEET-sə, Italian: [ˈpittsa]; Neapolitan: [ˈpittsə]) is an Italian dish consisting of a flat base of leavened wheat-based dough topped with tomato, cheese, and other ingredients, baked at a high temperature, traditionally in a wood-fired oven.[1]

The term pizza was first recorded in the year 997 AD, in a Latin manuscript from the southern Italian town of Gaeta, in Lazio, on the border with Campania.[2] Raffaele Esposito is often credited for creating modern pizza in Naples.[3][4][5][6] In 2009, Neapolitan pizza was registered with the European Union as a traditional speciality guaranteed dish. In 2017, the art of making Neapolitan pizza was added to UNESCO's list of intangible cultural heritage.[7]

Pizza and its variants are among the most popular foods in the world. Pizza is sold at a variety of restaurants, including pizzerias (pizza specialty restaurants), Mediterranean restaurants, via delivery, and as street food.[8] In Italy, pizza served in a restaurant is presented unsliced, and is eaten with the use of a knife and fork.[9][10] In casual settings, however, it is typically cut into slices to be eaten while held in the hand. Pizza is also sold in grocery stores in a variety of forms, including frozen or as kits for self-assembly. They are then cooked using a home oven.

In 2017, the world pizza market was US$128 billion, and in the US it was $44 billion spread over 76,000 pizzerias.[11] Overall, 13% of the U.S. population aged two years and over consumed pizza on any given day.[12]

Etymology

The oldest recorded usage of the word pizza is from a Latin text from the town of Gaeta, then still part of the Byzantine Empire, in 997 AD; the text states that a tenant of certain property is to give the bishop of Gaeta duodecim pizze (lit. 'twelve pizzas') every Christmas Day, and another twelve every Easter Sunday.[2][13]

Suggested etymologies include:

- Byzantine Greek and Late Latin pitta > pizza, cf. Modern Greek pitta bread and the Apulia and Calabrian (then Byzantine Italy) pitta,[14] a round flat bread baked in the oven at high temperature sometimes with toppings. The word pitta can in turn be traced to either Ancient Greek πικτή (pikte), 'fermented pastry', which in Latin became picta, or Ancient Greek πίσσα (pissa, Attic: πίττα, pitta), 'pitch',[15][16] or πήτεα (pḗtea), 'bran' (πητίτης, pētítēs, 'bran bread').[17]

- The Etymological Dictionary of the Italian Language explains it as coming from dialectal pinza, 'clamp', as in modern Italian pinze, 'pliers, pincers, tongs, forceps'. Their origin is from Latin pinsere, 'to pound, stamp'.[18]

- The Lombardic word bizzo or pizzo meaning 'mouthful' (related to the English words "bit" and "bite"), which was brought to Italy in the middle of the 6th century AD by the invading Lombards.[2][19] The shift b>p could be explained by the High German consonant shift, and it has been noted in this connection that in German the word Imbiss means 'snack'.

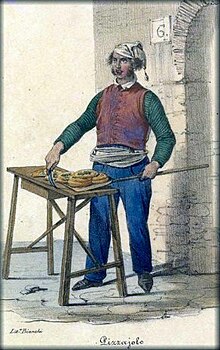

A small pizza is sometimes called pizzetta.[20] A person who makes pizza is known as a pizzaiolo.[21]

The word pizza was borrowed from Italian into English in the 1930s; before it became well known, pizza was called "tomato pie" by English speakers. Some regional pizza variations still use the name tomato pie.[22]

History

Records of pizza-like foods can be found throughout ancient history. In the 6th century BC, the Persian soldiers of the Achaemenid Empire during the rule of Darius the Great baked flatbreads with cheese and dates on top of their battle shields[23][24] and the ancient Greeks supplemented their bread with oils, herbs, and cheese.[25][26] An early reference to a pizza-like food occurs in the Aeneid, when Celaeno, queen of the Harpies, foretells that the Trojans would not find peace until they are forced by hunger to eat their tables (Book III). In Book VII, Aeneas and his men are served a meal that includes round cakes (like pita bread) topped with cooked vegetables. When they eat the bread, they realize that these are the "tables" prophesied by Celaeno.[27] In 2023, archeologists discovered a fresco in Pompeii appearing to depict a pizza-like dish among other foodstuffs and staples on a silver platter. Italy's culture minister said it "may be a distant ancestor of the modern dish".[28][29] The first mention of the word pizza comes from a notarial document written in Latin and dating to May 997 AD from Gaeta, demanding a payment of "twelve pizzas, a pork shoulder, and a pork kidney on Christmas Day, and 12 pizzas and a couple of chickens on Easter Day".[30]

Modern pizza evolved from similar flatbread dishes in Naples, Italy, in the 18th or early 19th century.[31] Before that time, flatbread was often topped with ingredients such as garlic, salt, lard, and cheese. It is uncertain when tomatoes were first added and there are many conflicting claims,[31] though it certainly could not have been before the 16th century and the Columbian Exchange. Pizza was sold from open-air stands and out of pizza bakeries until about 1830, when pizzerias in Naples started to have stanze with tables where clients could sit and eat their pizzas on the spot.[32]

A popular contemporary legend holds that the archetypal pizza, pizza Margherita, was invented in 1889, when the Royal Palace of Capodimonte commissioned the Neapolitan pizzaiolo (pizza maker) Raffaele Esposito to create a pizza in honor of the visiting Queen Margherita. Of the three different pizzas he created, the Queen strongly preferred a pizza swathed in the colors of the Italian flag—red (tomato), green (basil), and white (mozzarella). Supposedly, this kind of pizza was then named after the Queen,[33] with an official letter of recognition from the Queen's "head of service" remaining to this day on display in Esposito's shop, now called the Pizzeria Brandi.[34] Later research cast doubt on this legend, undermining the authenticity of the letter of recognition, pointing that no media of the period reported about the supposed visit and that both the story and name Margherita were first promoted in the 1930s–1940s.[35][36]

Pizza was taken to the United States by Italian immigrants in the late nineteenth century[37] and first appeared in areas where they concentrated. The country's first pizzeria, Lombardi's, opened in New York City in 1905.[38] Following World War II, veterans returning from the Italian Campaign, who were introduced to Italy's native cuisine, proved a ready market for pizza in particular.[39]

The Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana (lit. 'True Neapolitan Pizza Association') is a non-profit organization founded in 1984 with headquarters in Naples that aims to promote traditional Neapolitan pizza.[40] In 2009, upon Italy's request, Neapolitan pizza was registered with the European Union as a Traditional Speciality Guaranteed dish,[41][42] and in 2017 the art of its making was included on UNESCO's list of intangible cultural heritage.[7]

Preparation

Pizza is sold fresh or frozen, and whole or in portion-size slices. Methods have been developed to overcome challenges such as preventing the sauce from combining with the dough, and producing a crust that can be frozen and reheated without becoming rigid. There are frozen pizzas with raw ingredients and self-rising crusts.

Another form of pizza is available from take and bake pizzerias. This pizza is assembled in the store, then sold unbaked to customers to bake in their own ovens. Some grocery stores sell fresh dough along with sauce and basic ingredients, to assemble at home before baking in an oven.

- Pizza preparation

-

Traditional pizza dough being tossed

-

Toppings being placed on pan pizzas

-

An unbaked Neapolitan pizza on a metal peel, ready for the oven

-

A wrapped, mass-produced frozen pizza to be baked at home

Baking

In restaurants, pizza can be baked in an oven with fire bricks above the heat source, an electric deck oven, a conveyor belt oven, or, in traditional style in a wood or coal-fired brick oven. The pizza is slid into the oven on a long paddle, called a peel, and baked directly on hot bricks, a screen (a round metal grate, typically aluminum), or whatever the oven surface is. Before use, a peel is typically sprinkled with cornmeal to allow the pizza to easily slide on and off it.[43] When made at home, a pizza can be baked on a pizza stone in a regular oven to reproduce some of the heating effect of a brick oven. Cooking directly on a metal surface results in too rapid heat transfer to the crust, burning it.[44] Some home chefs use a wood-fired pizza oven, usually installed outdoors. As in restaurants, these are often dome-shaped, as pizza ovens have been for centuries,[45] in order to achieve even heat distribution. Another variation is grilled pizza, in which the pizza is baked directly on a barbecue grill. Greek pizza, like deep dish Chicago and Sicilian style pizza, is baked in a pan rather than directly on the bricks of the pizza oven.

Most restaurants use standard and purpose-built pizza preparation tables to assemble their pizzas. Mass production of pizza by chains can be completely automated.

- Pizza baking

-

Pizzas baking in a traditional wood-fired brick oven

-

A pizza being removed with a wooden peel

-

Charred crust on a pizza Margherita, an acceptable trait in artisanal pizza

-

Pizza grilling on an outdoor gas range

Crust

The bottom of the pizza, called the "crust", may vary widely according to style – thin as in a typical hand-tossed Neapolitan pizza or thick as in a deep-dish Chicago-style. It is traditionally plain, but may also be seasoned with garlic or herbs, or stuffed with cheese. The outer edge of the pizza is sometimes referred to as the cornicione.[46] Some pizza dough contains sugar, to help its yeast rise and enhance browning of the crust.[47]

Dipping sauce specifically for pizza was invented by American pizza chain Papa John's Pizza in 1984 and has since been adopted by some when eating pizza, especially the crust.[48]

Cheese

Mozzarella cheese is commonly used on pizza, with the buffalo mozzarella produced in the surroundings of Naples.[49] Other cheeses are also used, particularly Italian cheeses including provolone, pecorino romano, ricotta, and scamorza. Less expensive processed cheeses or cheese analogues have been developed for mass-market pizzas to produce desirable qualities like browning, melting, stretchiness, consistent fat and moisture content, and stable shelf life. This quest to create the ideal and economical pizza cheese has involved many studies and experiments analyzing the impact of vegetable oil, manufacturing and culture processes, denatured whey proteins, and other changes in manufacture. In 1997, it was estimated that annual production of pizza cheese was 1 million metric tons (1,100,000 short tons) in the U.S. and 100,000 metric tons (110,000 short tons) in Europe.[50]

Varieties and styles

A great number of pizza varieties exist, defined by the choice of toppings and sometimes also crust. There are also several styles of pizza, defined by their preparation method. The following lists feature only the notable ones.

Varieties

| Image | Name | Characteristic ingredients | Origin | First attested | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pizza Margherita | Tomatoes, mozzarella, basil. | Naples, Italy | June 1889 | The archetypical Neapolitan pizza. |

|

Pizza marinara | Tomato sauce, olive oil, oregano, garlic. No cheese. | Naples, Italy | 1734 | One of the oldest Neapolitan pizza. |

|

Pizza capricciosa | Ham, mushrooms, artichokes, egg. | Rome, Lazio, Italy | 1937 | Similar to pizza quattro stagioni, but with toppings mixed rather than separated. |

|

Pizza quattro formaggi | Prepared using four kinds of cheese (Italian: [ˈkwattro forˈmaddʒi], "four cheeses"): mozzarella, Gorgonzola and two others depending on the region. | Lazio, Italy | Its origins are not clearly documented, but it is believed to originate from the Lazio region at the beginning of the 18th century.[51] | |

|

Pizza quattro stagioni | Artichokes, mushroom, ham, tomatoes. | Campania, Italy | The toppings are separated by quarter, representing the cycle of the seasons. | |

|

Pizza pugliese | Tomatoes, onion, mozzarella. | Apulia, Italy | ||

|

Seafood pizza | Seafood, such as fish, shellfish or squid. | Italy | Subvarieties include pizza ai frutti di mare (no cheese) and pizza pescatore (with mussels or squid). | |

|

Hawaiian pizza | Pineapple, ham or bacon. | Canada | 1962 | Tends to divide opinion.[52][53] |

Styles

| Image | Name | Characteristics | Origin | First attested |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Calzone | Pizza folded in half turnover-style. | Naples, Italy | 1700s |

|

Pizzetta | Small pizza served as an hors d'oeuvre or snack. | Italy | |

|

Deep-fried pizza | The pizza is deep-fried (cooked in oil) instead of baked. | Italy and Scotland | |

|

California-style pizza | Distinguished by the use of non-traditional ingredients, especially varieties of fresh produce. | California, U.S. | 1980 |

|

Chicago-style pizza | Baked in a pan with a high edge that holds in a thick layer of toppings. The crust is sometimes stuffed with cheese or other ingredients. | Chicago, U.S. | c. 1940s |

|

Colorado-style pizza | Made with a characteristically thick, braided crust topped with heavy amounts of sauce and cheese. It is traditionally served by the pound, with a side of honey as a condiment. | Colorado, U.S. | 1973 |

|

Detroit-style pizza | The cheese is spread to the edges and caramelizes against the high-sided heavyweight rectangular pan, giving the crust a lacy, crispy edge. | Detroit, U.S. | 1946 |

|

Grandma pizza | Thin, square, baked in a sheet pan, "reminiscent of pizzas cooked at home by Italian housewives without a pizza oven".[54] | Long Island, U.S. | Early 1900s |

| Greek pizza | Proofed and baked in a shallow pan; the crust is light and similar to focaccia. | Connecticut, U.S. | 1955 | |

|

Italian tomato pie | Made from thick dough covered by tomato paste; a variation on Sicilian pizza. Also called pizza strips (when cut as in the image), gravy pie, church pie, red bread, party pizza, etc. | U.S. | Early 1900s |

|

Jumbo slice | Very large slice of pizza sold as street food. | New York and Washington, D.C., U.S. | 1981 |

|

New York–style pizza | Neapolitan-derived pizza with a characteristic thin foldable crust. | New York metropolitan area (and beyond) | Early 1900s |

|

St. Louis–style pizza | The style has a thin cracker-like crust made without yeast, generally uses Provel cheese, and is cut into squares or rectangles instead of wedges. | St. Louis, U.S. | 1945 |

By region of origin

Italy

Authentic Neapolitan pizza (Italian: pizza napoletana) is made with San Marzano tomatoes, grown on the volcanic plains south of Mount Vesuvius, and either mozzarella di bufala campana, made with milk from water buffalo raised in the marshlands of Campania and Lazio[55] or fior di latte. Buffalo mozzarella is protected with its own European protected designation of origin.[55] Other traditional pizzas include pizza marinara, which is topped with marinara sauce and is supposedly the most ancient tomato-topped pizza,[56] pizza capricciosa, which is prepared with mozzarella cheese, baked ham, mushroom, artichoke, and tomato,[57] and pizza pugliese, prepared with tomato, mozzarella, and onions.[58]

A popular variant of pizza in Italy is Sicilian pizza (locally called sfincione or sfinciuni),[59][60] a thick-crust or deep-dish pizza originating during the 17th century in Sicily: it is essentially a focaccia that is typically topped with tomato sauce and other ingredients. Until the 1860s, sfincione was the type of pizza usually consumed in Sicily, especially in the Western portion of the island.[61] Other variations of pizzas are also found in other regions of Italy, for example pizza al padellino or pizza al tegamino, a small-sized, thick-crust, deep-dish pizza typically served in Turin, Piedmont.[62][63][64]

United States

The first pizzeria in the U.S. was opened in New York City's Little Italy in 1905.[65] Common toppings for pizza in the United States include anchovies, ground beef, chicken, ham, mushrooms, olives, onions, peppers, pepperoni, salami, sausage, spinach, steak, and tomatoes. Distinct regional types developed in the 20th century, including Buffalo,[66] California, Chicago, Detroit, Greek, New Haven, New York, and St. Louis styles.[67] These regional variations include deep-dish, stuffed, pockets, turnovers, rolled, and pizza-on-a-stick, each with seemingly limitless combinations of sauce and toppings.

Thirteen percent of the United States population consumes pizza on any given day.[68] Pizza chains such as Domino's Pizza, Pizza Hut, and Papa John's, pizzas from take and bake pizzerias, and chilled or frozen pizzas from supermarkets make pizza readily available nationwide.

Argentina

Argentine pizza is a mainstay of the country's cuisine,[69] especially of its capital Buenos Aires, where it is regarded as a cultural heritage and icon of the city.[70][71][72] Argentina is the country with the most pizzerias per inhabitant in the world and, although they are consumed throughout the country, the highest concentration of pizzerias and customers is Buenos Aires, the city with the highest consumption of pizzas in the world (estimated in 2015 to be 14 million per year).[73] As such, the city has been considered as one of the world capitals of pizza.[71][73] The dish was introduced to Buenos Aires in the late 19th century with the massive Italian immigration, as part of a broader great European immigration wave to the country.[71] Thus, around the same time that the iconic pizza Margherita was being invented in Italy, pizza were already being cooked in the Argentine capital.[74] The impoverished Italian immigrants that arrived to the city transformed the originally modest dish into a much more hefty meal, motivated by the abundance of food in Argentina.[73][75] In the 1930s, pizza was cemented as a cultural icon in Buenos Aires, with the new pizzerias becoming a central space for sociability for the working class people who flocked to the city.[75][74]

The most characteristic style of Argentine pizza—which almost all the classic pizzerias in Buenos Aires specialize in—is the so-called pizza de molde (Spanish for 'pizza in the pan'), characterized by having a "thick, spongy base and elevated bready crust".[71] This style, which today is identified as the typical style of Argentine pizza—characterized by a thick crust and a large amount of cheese—arose when impoverished Italian immigrants found a greater abundance of food in then-prosperous Argentina, which motivated them to transform the originally modest dish into a much more hefty meal suitable for a main course.[73][75] The name pizza de molde emerged because there were no pizza ovens in the city, so bakers resorted to baking them in pans.[76] Since they used bakery plates, Argentine pizzas were initially square or rectangular, a format associated with the 1920s that is still maintained in some classic pizzerias, especially for vegetable pizzas, fugazzetas or fugazzas.[76]

Other styles of Argentine pizza include the iconic fugazza and its derivative fugazzeta or fugazza con queso (a terminology that varies depending on the pizzeria),[71] or the pizza de cancha or canchera (a cheese-less variant).[77] Most pizza menus include standard flavor combinations, including the traditional plain mozzarella, nicknamed "muza" or "musa"; the napolitana or "napo", with "cheese, sliced tomatoes, garlic, dried oregano and a few green olives", not to be confused with Neapolitan pizza;[71] calabresa, with slices of longaniza;[78] jamon y morrones, with sliced ham and roasted bell peppers;[71] as well as versions with provolone, with anchovies,[78] with hearts of palm, or with chopped hard boiled egg.[71] A typical custom that is unique to Buenos Aires is to accompany pizza with fainá, a pancake made from chickpea flour.[79]

Records

As of 2021[update], according to Guinness World Records:

- The world's largest pizza was prepared in Rome in December 2012, and measured 1,261 square meters (13,570 square feet). The pizza was named "Ottavia" in homage to the first Roman emperor Octavian Augustus, and was made with a gluten-free base.[80]

- The world's longest pizza was 1,930.39 meters (6,333 feet 3+1⁄2 inches) long; it was made in Fontana, California, in 2017.[81] Other previous records include that of Marquinetti (Tomelloso, Spain), where a 1141.5 m pizza was achieved, itself surpassing a previous record in Poland.[82]

- The world's most expensive commercially available pizza recognised by Guinness World Records costs US$2,700, and was sold at Industry Kitchen (USA) in New York City, New York, as of 24 April 2017. It is made of black squid ink dough, and topped with UK white Stilton cheese, French foie gras and truffles, Ossetra caviar from the Caspian Sea, Almas caviar, and 24K gold leaves.[83]

- More expensive pizzas have been reported, but are not recognised by Guinness World Records, such as the £4,200 "Pizza Royale 007" at Haggis restaurant in Glasgow, Scotland, which is topped with caviar, lobster, and 24-carat gold dust, and the US$1,000 caviar pizza made by Nino's Bellissima pizzeria in New York City, New York.[84]

- A pizza made by the restaurateur Domenico Crolla that included toppings such as sunblush-tomato sauce, Scottish smoked salmon, medallions of venison, edible gold, lobster marinated in cognac, and champagne-soaked caviar. The pizza was auctioned for charity in 2007, raising £2,150.[85]

Pizza and health

Some pizzas mass-produced by pizza chains have been criticized as having an unhealthy balance of ingredients. Pizza can be high in salt and fat, and is high in calories. The USDA reports an average sodium content of 5,100 mg per 14 in (36 cm) pizza in fast food chains.[86] There are concerns about undesirable health effects.[87][88]

Similar dishes

- Calzone and stromboli are similar dishes that are often made of pizza dough folded (calzone) or rolled (stromboli) around a filling.

- Panzerotti are similar to calzoni, but fried rather than baked.

- Piadina is a thin Italian flatbread, typically prepared in the Romagna historical region.

- Focaccia is a flat leavened oven-baked Italian bread, similar in style and texture to pizza; in some places, it is called pizza bianca (lit. 'white pizza').[89]

- Farinata or cecina.[90] A Ligurian (farinata) and Tuscan (cecina) regional dish made from chickpea flour, water, salt, and olive oil. Also called socca in the Provence region of France. Often baked in a brick oven, and typically weighed and sold by the slice.

- Coca is a similar dish consumed mainly in Catalonia and neighbouring regions, but that has extended to other areas in Spain, and to Algeria. There are sweet and savoury versions.

- The Alsatian flammekueche[91] (standard German: Flammkuchen; French: tarte flambée) is a thin disc of dough covered in crème fraîche, onions, and bacon.

- Garlic fingers is an Atlantic Canadian dish, similar to a pizza in shape and size, and made with similar dough. It is garnished with melted butter, garlic, cheese, and sometimes bacon.

- The Anatolian lahmacun (Arabic: laḥm bi'ajīn; Armenian: lahmajoun; also Turkish pizza or Armenian pizza) is a meat-topped dough round. The base is very thin, and the layer of meat often includes chopped vegetables.[92]

- The Levantine manakish (Arabic: ma'ujnāt) and sfiha (Arabic: laḥm bi'ajīn; also Arab pizza) are dishes similar to pizza.

- Panizza is half a stick of bread (often baguette), topped with the usual pizza ingredients, baked in an oven.

- The Macedonian pastrmalija is a bread pie made from dough and meat. It is usually oval-shaped with chopped meat on top of it.

- The Provençal pissaladière is similar to an Italian pizza, with a slightly thicker crust and a topping of cooked onions, anchovies, and olives.

- Pizza bagel is a bagel with toppings similar to that of traditional pizzas.

- Pizza bread is an open-faced sandwich made of bread, tomato sauce, cheese,[93] and various toppings.

- Pizza sticks are baked with pizza dough and pizza ingredients.[94] Bread dough may also be used in their preparation,[95] and some versions are fried.[96]

- Pizza snack rolls are a trade-marked commercial product.

- Okonomiyaki, a Japanese dish cooked on a hotplate, is often referred to as "Japanese pizza".[97]

- Zanzibar pizza is a street food served in Stone Town, Zanzibar, Tanzania. It uses a dough much thinner than pizza dough, almost like filo dough, filled with minced beef, onions, and an egg, similar to Moroccan basṭīla.[98]

- Zwiebelkuchen, a German onion tart, often baked with diced bacon and caraway seeds.

See also

![]() Media related to Pizzas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pizzas at Wikimedia Commons

- Italian cuisine

- List of Italian dishes

- List of pizza chains

- List of pizza varieties by country

- List of baked goods

- Antica Pizzeria Port'Alba – pizzeria in Naples, Italy

- Flammekueche – food speciality of the Alsace region

- Khachapuri – Georgian cheese-filled bread

- Lahmacun – Middle Eastern flatbread with minced meat

- Manakish – Levantine flatbread dish

- Matzah pizza – Jewish pizza dish

- Wähe – Swiss type of tart

- Pizza cake – multiple-layer pizza

- Pizza cheese – cheese for use specifically on pizza

- Pizza in China – overview of the role of pizza in China

- Pizza delivery – service in which a pizzeria delivers pizza to a customer

- Pizza farm – farm split into sections like a pizza split into slices

- Pizza party – social gathering at which pizza is eaten

- Pizza saver – object used to prevent the top of a food container from collapsing

- Pizza strips – a tomato pie of Italian-American origin

- Pizza theorem – equality of areas of alternating sectors of a disk with equal angles through any interior point

References

- ^ "144843". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b c Maiden, Martin. "Linguistic Wonders Series: Pizza is a German(ic) Word". yourDictionary.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2003.

- ^ Arthur Schwartz, Naples at Table: Cooking in Campania (1998), p. 68. ISBN 9780060182618.

- ^ John Dickie, Delizia!: The Epic History of the Italians and Their Food (2008), p. 186.

- ^ Father Giuseppe Orsini, Joseph E. Orsini, Italian Baking Secrets (2007), p. 99.

- ^ "Pizza Margherita: History and Recipe". ITALY Magazine. 14 March 2011. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Naples' pizza twirling wins Unesco 'intangible' status". The Guardian. London. Agence France-Presse. 7 December 2017. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Miller, Hanna (April–May 2006). "American Pie". American Heritage. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ Naylor, Tony (6 September 2019). "How to eat: Neapolitan-style pizza". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ Godoy, Maria (13 January 2014). "Italians To New Yorkers: 'Forkgate' Scandal? Fuhggedaboutit". The Salt (blog). National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ Hynum, Rick. "Pizza Power 2017 – A State of the Industry Report". PMQ Pizza Magazine. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ Rhodes, Donna; et al. (February 2014). "Consumption of Pizza" (PDF). Food Surveys Research Group Dietary Data Brief No. 11. USDA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Salvatore Riciniello (1987) Codice Diplomatico Gaetano, Vol. I, La Poligrafica

- ^ Babiniotis, Georgios (2005). Λεξικό της Νέας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας [Dictionary of Modern Greek] (in Greek). Lexicology Centre. p. 1413. ISBN 978-960-86190-1-2.

- ^ "Pizza, at Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ^ "Pissa, Liddell and Scott, "A Greek-English Lexicon, at Perseus". Perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ^ "Pizza, at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ^ 'pizza' Archived 21 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ "Pizza". Garzanti Linguistica. De Agostini Scuola Spa. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "Definition of pizzetta". Merriam-Webster. 22 June 2023.

- ^ Doane, Seth (20 November 2022). "Bringing authentic Neapolitan pizza home". CBS News.

- ^ Uyehara, Mari (6 October 2023). "The Many Lives of Tomato Pie". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ "Pizza, A Slice of American History" Liz Barrett (2014), p.13

- ^ "The Science of Bakery Products" W. P. Edwards (2007), p.199

- ^ Talati-Padiyar, Dhwani (8 March 2014). Travelled, Tasted, Tried & Tailored: Food Chronicles. Lulu publishers. ISBN 978-1304961358. Retrieved 18 November 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Buonassisi, Rosario (2000). Pizza: From its Italian Origins to the Modern Table. Firefly. p. 78.

- ^ "Aeneas and Trojans fulfill Anchises' prophecy". Archived from the original on 29 March 2017.

- ^ "Pompeii archaeologists discover 'pizza' painting". BBC News. 17 June 2023.

- ^ "Pizza's possible 'distant ancestor' found painted in the ruins of Pompeii". ABC News. 27 June 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "Sorpresa: la parola "pizza" è nata a Gaeta" ["Surprise: the word "pizza" was born in Gaeta]. La Reppublica (in Italian). 9 February 2015. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ a b Helstosky, Carol (2008). Pizza: A Global History. London: Reaktion. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-1-86189-391-8.

- ^ de Sanctis, Francesco. La giovinezza di Francesco de Sanctis: frammento autobiografico. p. 39.

In the evening we often used to go eating pizza in some rooms at the Piazza della Carità

- ^ "Pizza Margherita: History and Recipe". Italy Magazine. 14 March 2011. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Hales, Dianne (12 May 2009). Sök på Google (in Swedish). Crown. ISBN 978-0767932110. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ "Was margherita pizza really named after Italy's queen?". BBC Food. 28 December 2012. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ Nowak, Zachary (March 2014). "Folklore, Fakelore, History: Invented Tradition and the Origins of the Pizza Margherita". Food, Culture & Society. 17 (1): 103–124. doi:10.2752/175174414X13828682779249. ISSN 1552-8014. S2CID 142371201.

- ^ Helstosky, Carol (2008). Pizza: A Global History. Reaktion Books. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-86189-630-8.

- ^ Nevius, Michelle; Nevius, James (2009). Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City. New York: Free Press. pp. 194–95. ISBN 978-1416589976.

- ^ Turim, Gayle. "A Slice of History: Pizza Through the Ages". History.com. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ^ "Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana (AVPN)". Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ Official Journal of the European Union, Commission regulation (EU) No 97/2010 Archived 3 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 5 February 2010

- ^ International Trademark Association, European Union: Pizza napoletana obtains "Traditional Speciality Guaranteed" status Archived 19 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine, 1 April 2010

- ^ Owens, Martin J. (2003). Make Great Pizza at Home. Taste of America Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-9744470-0-1. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ Chen, Angus (23 July 2018). "Pizza Physics: Why Brick Ovens Bake The Perfect Italian-Style Pie". NPR. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "pizza oven kits". Californo. Archived from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Braimbridge, Sophie; Glynn, Joanne (2005). Food of Italy. Murdoch Books. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-74045-464-3. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ DeAngelis, Dominick A. (1 December 2011). The Art of Pizza Making: Trade Secrets and Recipes. The Creative Pizza Company. pp. 20–28. ISBN 978-0-9632034-0-3.

- ^ Shrikant, Adit (27 July 2017). "How Dipping Sauce for Pizza Became Oddly Necessary". Eater. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 27 July 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ Anderson, Sam (11 October 2012). "Go Ahead, Milk My Day". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Fox, Patrick F.; et al. (2000). Fundamentals of Cheese Science. Aspen Pub. p. 482. ISBN 978-0-8342-1260-2. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016.

- ^ "La pizza 4 fromages : origines et recettes". Restaurant le Quatre Vingt. 31 May 2017.

- ^ Dowling, Stephen; Gray, Richard (20 August 2022). "A pizza topping that divides the world". BBC. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Giuffrida, Angela (27 June 2023). "Pompeii fresco find possibly depicts 2,000-year-old form of pizza". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ Rosengarten, David (15 August 2013). "Za-Za-Zoom: The 'Grandma Pizza' Forges Ahead In New York". Forbes. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Selezione geografica". Europa.eu.int. 23 February 2009. Archived from the original on 18 February 2005. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- ^ "La vera storia della pizza napoletana". Biografieonline.it. 20 May 2013. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Guides, Rough (1 August 2011). Rough Guides (ed.). Rough Guide Phrasebook: Italian: Italian. Penguin. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-4053-8646-3. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ Wine Enthusiast, Volume 21, Issues 1–7. Wine Enthusiast. 2007. p. 475. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "What is Sicilian Pizza?". WiseGeek. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ Giorgio Locatelli (26 December 2012). Made In Sicily. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-213038-9. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ Gangi, Roberta (2007). "Sfincione". Best of Sicily Magazine. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014.

- ^ "Torino: la riscoperta della pizza al padellino". Agrodolce. 3 April 2014. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ "Pizza al padellino (o tegamino): che cos'è?". Gelapajo.it. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ "Beniamino, il profeta della pizza gourmet". Torino – Repubblica.it. 19 January 2013. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Otis, Ginger Adams (2010). New York City 7. Lonely Planet. p. 256. ISBN 978-1741795912. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Bovino, Arthur (13 August 2018). "Is America's Pizza Capital Buffalo, New York?". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "Pizza Garden: Italy, the Home of Pizza". CUIP Chicago Public Schools – University of Chicago Internet Project. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Rhodes, Donna G.; Adler, Meghan E.; Clemens, John C.; LaComb, Randy P.; Moshfegh, Alanna J. "Consumption of Pizza" (PDF). Food Surveys Research Group. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ Aeberhard, Danny; Benson, Andrew; Phillips, Lucy (2000). The Rough Guide to Argentina. Rough Guides. p. 40. ISBN 978-185-828-569-6. Retrieved 10 December 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ Pizzerías de valor patrimonial de Buenos Aires (2008), p. 11

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lazar, Allie (25 April 2016). "Buenos Aires Makes Some of the World's Best (and Weirdest) Pizza". Saveur. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Sorba, Pietro (15 October 2021). "La reivindicación de la pizza de molde argentina". Clarín (in Spanish). Buenos Aires. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d Gómez, Leire (17 July 2015). "Buenos Aires: la ciudad de la pizza". Tapas (in Spanish). Madrid: SpainMedia. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b Hidalgo, Joaquín; Auzmendi, Martín (6 October 2018). "De Nápoles a la Argentina: la historia de la pizza y cómo llegó a ser un emblema nacional". Entremujeres. Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Acuña, Cecilia (26 June 2017). "La historia de la pizza argentina: ¿de dónde salió la media masa?". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ a b Pepe Arias, Gimena (25 June 2022). "Pizza a la piedra vs. pizza al molde: dos estilos que dividen a los argentinos". Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Firpo, Hernán (20 October 2018). "Angelín cumple 80 años: mitos y verdades de una pizzería indispensable". Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Tipos de pizzas en Argentina". Diario Democracia (in Spanish). Junín. 10 January 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ Booth, Amy (10 May 2022). "Buenos Aires' unusual pizza topping". BBC Travel. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Largest pizza". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ "Longest pizza". Guinness World Records. 10 June 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ "Longest pizza in Spain". Diario Lanza Digital. 31 May 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ "Most expensive pizza commercially available". Guinness World Records. 24 April 2017. Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ Shaw, Bryan (11 March 2010). "Top Five Most Expensive Pizzas in The World". Haute Living. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ "Chef cooks £2,000 Valentine pizza". BBC News. 14 February 2007. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ "Basic Report 21299: Fast Food, Pizza Chain, 14" pizza, cheese topping, regular crust". National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. 28 September 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "Survey of pizzas". Food Standards Agency. 8 July 2004. Archived from the original on 28 December 2005. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- ^ "Health | Fast food salt levels "shocking"". BBC News. 18 October 2007. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- ^ Riolo, A. (2012). The Mediterranean Diabetes Cookbook. American Diabetes Association. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-58040-483-9.

- ^ "Brick Oven Cecina". Fornobravo.com. Archived from the original on 16 October 2006. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- ^ Helga Rosemann, Flammkuchen: Ein Streifzug durch das Land der Flammkuchen mit vielen Rezepten und Anregungen (Offenbach: Höma-Verlag, 2009).

- ^ McKernan, Bethan (27 October 2016). "A 'pizza war' has broken out between Turkey and Armenia". The Independent. Archived from the original on 17 December 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ Adler, Karen; Fertig, Judith (2014). Patio Pizzeria. Running Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7624-4966-8. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ McNair, James (2000). James McNair's New Pizza. Chronicle Books. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-8118-2364-7. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ Magee, Elaine (2009). The Flax Cookbook. Da Capo Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-7867-3062-9. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ Wilbur, Todd (1997). Top Secret Restaurant Recipes. Penguin. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-4406-7440-2. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ "hanamiweb.com". Archived from the original on 18 March 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ^ Samuelsson, Marcus (2006). The soul of a new cuisine : a discovery of the foods and flavors of Africa. Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7645-6911-1. OCLC 61748426.

Further reading

- "The Saveur Ultimate Guide to Pizza". Saveur. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- Kliman, Todd (5 September 2012). "Easy as pie: A Guide to Regional Pizza". The Washingtonian. Explanation of eight pizza styles: Maryland, Roman, "Gourmet" Wood-fired, Generic boxed, New York, Neapolitan, Chicago, and New Haven.

- Helstosky, Carol (2008). Pizza: A Global History. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-391-8. OCLC 225876066.

- Chudgar, Sonya (22 March 2012). "An Expert Guide to World-Class Pizza". QSR Magazine. Retrieved 16 October 2012.* Raichlen, Steven (2008). The Barbecue! Bible. Workman Publishing. pp. 381–384. ISBN 978-0761149446.

- Delpha, J.; Oringer, K. (2015). Grilled Pizza the Right Way. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-62414-106-5.