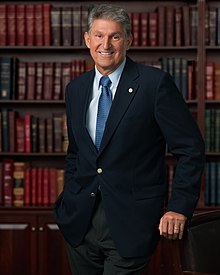

Political positions of Joe Manchin

The political positions of Joe Manchin encompass the established political and economic positions taken by Joe Manchin, the senior United States senator from West Virginia. Manchin's positions are reflected in his voting record, public speeches, and interviews. A member of the Democratic Party, Manchin is characterized by his self-described moderate beliefs.

In the 117th Congress, Manchin wielded power as a swing vote amid a deadlocked Senate.[1]

Political philosophy[edit]

I'm a West Virginia Democrat. I'm not a Washington Democrat. We're a little different. I don't subscribe to all of this very liberal, extreme liberal—I'm a centrist, moderate conservative Democrat.

—Manchin explaining his political beliefs[2]

Manchin is characterized as a moderate to conservative senator. His noted opposition to several issues within the Democratic Party agenda—including access to abortion, firearm regulation, and anti-business legislation—have garnered him criticism from within the party, although he has supported a majority of Joe Biden's nominations[3] and voted with him nearly 89% of the time, according to FiveThirtyEight.[4] He has been referred to as a moderate Democrat by The Hill[5] and Reuters[6] Simultaneously, Politico[7] and The Atlantic[8] have labelled him as a conservative Democrat, a descriptor he himself uses.[2] In August 2023, Manchin spoke to West Virginian radio personality Hoppy Kercheval to state his opposition to both parties. In the interview, he claimed that he was considering becoming an independent.[9]

Manchin's political philosophy is marked by bipartisanship; unfettered, the agenda of the Democratic Party will not maintain the political support that he has in West Virginia.[10] He has been described as a "blue dog", referring to a political philosophy of fiscally conservative Democrats that value working-class Americans.[11] Manchin supported Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski's reelection bids, two moderate Republicans in the Senate. Likewise, Murkowski has endorsed Manchin.[12] He was made an honorary co-chair of the centrist group No Labels, but stepped down in November 2014.[13] He returned to the organization three years later with Collins.[14]

Economic policy[edit]

Build Back Better Act[edit]

In November 2021, the Build Back Better Act passed the House of Representatives. Citing several factors—such as inflation, federal debt, and the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant, Manchin publicly opposed the bill on Fox News Sunday. Then-White House press secretary Jen Psaki called his opposition to the bill a "breach of his commitments" to Democrats;[15] Manchin had quietly presented the White House with an alternative deal comparable in size that excluded funding for housing and racial equity initiatives.[16]

Manchin was an architect of domestic-oriented Inflation Reduction Act and co-sponsored the bill with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer. The deal included a total of US$700 billion for energy and climate spending, deficit reduction, subsidies for Affordable Care Act premiums, prescription drug reform, and tax alterations; Manchin stated that the act would have gone farther [17] During a state dinner at the White House, French president Emmanuel Macron accused Manchin of hurting his country, following the passage of Inflation Reduction Act.[18]

Cryptocurrency[edit]

Manchin is an opponent to cryptocurrency, particularly Bitcoin. With Schumer, he sought a crackdown on Bitcoin in June 2011.[19] In February 2014, following the collapse of the cryptocurrency exchange Mt. Gox, he sent a letter to several economic figures—including then United States Department of the Treasury secretary Jack Lew, then Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen, and then Securities and Exchange Commission chair Mary Jo White—asking for Bitcoin to be banned.[20]

Energy and environmental policy[edit]

In 1987, faced with a low-paying job in the West Virginia Senate and his family's struggling carpet business, Manchin assisted a Grant Town, West Virginia power plant with clearing bureaucratic hurdles. With his brother, Roch, Manchin founded the waste coal brokerage company Enersystems in 1988. Through Enersystems, Manchin provided the plant with coal refuse. He is a vocal opponent to regulation of materials.[21]

As part of the Inflation Reduction Act, consumers who purchase electric vehicles are eligible for a federal tax credit, despite Manchin describing such credits as "ludicrous".[22] In January 2023, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) delayed implementing the tax credit to determine how to enforce the guidance in the Inflation Reduction Act. In response, Manchin introduced a bill to halt the credit until battery requirements can be introduced; the bill would also rescind some credits.[23] He vowed to sue the Biden administration in March.[24]

Social issues[edit]

Abortion[edit]

Following Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization (2022), a landmark decision that held that the Constitution does not guarantee the right to an abortion and overturned Roe v. Wade (1973), Manchin expressed disappointment. He stated that Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, who helped deliver the majority opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization and whom he nominated in 2017 and 2018, misled him.[25] Although he expressed hope that—despite being raised as pro-life—Republicans would restore Roe v. Wade,[26] he joined Republicans in opposing the Women's Health Protection Act.[27] Manchin stated that he would support a narrower bill that codified Roe v. Wade.[28]

Donald Trump[edit]

In response to the January 6 Capitol attack, Twitter temporarily locked Donald Trump's account for 12 hours. In response, Manchin asked for Twitter to lock his account for two weeks.[29]

Technology[edit]

Manchin has advocated for broadband in West Virginia. In December 2018, he lifted his hold on nominating Brendan Carr as the commissioner of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) after Carr stated his commitment to fund wireless broadband in rural areas.[30] With 11 other legislators, he urged then-FCC chairman Ajit Pai—whom he voted for in 2017[31]—to crowdsource its statistics on broadband speeds in 2019.[32] Joined by senators Angus King, Michael Bennet, and Rob Portman, he called for the Federal Communications Commission to define high-speed broadband as 100Mbps down and 100Mbps up from 25Mbps down and 3Mbps.[33] Manchin revived the See Something, Say Something Online Act with senator John Cornyn in January 2021, an act he previously sponsored in August 2021, to require online platforms to report illegal activities—such as the sale of opioids—to law enforcement, weakening the power of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.[34] Manchin opposed Biden's nomination of Gigi Sohn as the FCC's commissioner citing her association with "far-left groups", in apparent reference to her work with the Electronic Frontier Foundation.[35]

References[edit]

- ^ Everett, Burgess (February 7, 2021). "'The Democratic version of John McCain'". Politico. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Colegrove, Andrew (November 9, 2016). "Senator Manchin refutes speculation of a party switch". WSAZ. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Prokop, Andrew (April 27, 2021). "Joe Manchin wants to save Democrats from themselves". Vox. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ "Does Your Member Of Congress Vote With Or Against Biden?". FiveThirtyEight. January 3, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Stanage, Niall (July 16, 2022). "Five times Joe Manchin has bucked the Democrats". The Hill. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ "Democratic senator criticizes Pelosi's immigration comment". Reuters. January 28, 2018. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Kruse, Michael; Everett, Burgess (March 2017). "Manchin in the Middle". Politico. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Foran, Clare (May 9, 2017). "West Virginia's Conservative Democrat Gets a Primary Challenger". The Atlantic. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Hughes, Siobhan (August 10, 2023). "Joe Manchin Weighs Leaving Democratic Party". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "Understanding The Politics Of Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin". All Things Considered. NPR. July 17, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Brakey, Eric (November 3, 2021). "Joe Manchin and the blue-collar exodus". The Hill. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Kilgore, Ed (February 7, 2022). "What's the Point of Manchin and Murkowski Endorsing Each Other?". Intelligencer. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Everett, Burgess (November 7, 2014). "Manchin quits centrist No Labels". Politico. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Needham, Vicki (November 6, 2017). "Collins, Manchin to serve as No Labels co-chairs". The Hill. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Yen, Hope; Fram, Alan (December 19, 2021). "Manchin not backing Dems' $2T bill, potentially dooming it". Associated Press. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Stein, Jeff (January 8, 2022). "Manchin's $1.8 trillion spending offer appears no longer to be on the table". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Everett, Burgess; Levine, Marianne (July 27, 2022). "Manchin's latest shocker: A $700B deal". Politico. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Ward, Alexander; Lynch, Suzanne (January 19, 2023). "'You're hurting my country': Manchin faces Europe's wrath". Politico. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Wolf, Brett (June 8, 2011). "Senators seek crackdown on "Bitcoin" currency". Reuters. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Jeffries, Adrianne (February 26, 2014). "Senator calls on the US government to ban Bitcoin". The Verge. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Flavelle, Christopher; Tate, Julie (March 27, 2022). "How Joe Manchin Aided Coal, and Earned Millions". The New York Times. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Hawkins, Andrew (July 28, 2022). "EV tax credits are back — and bigger — in new Senate climate bill". The Verge. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Hawkins, Andrew (January 25, 2023). "Joe Manchin is trying to derail the EV tax credit he helped craft". The Verge. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Gitlin, Jonathan (March 30, 2023). "Manchin vows to sue Biden administration over EV tax credits". Ars Technica. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Kapur, Sahil (June 24, 2023). "Collins and Manchin suggest they were misled by Kavanaugh and Gorsuch on Roe". NBC News. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Weissmann, Jordan (June 24, 2022). "Joe Manchin Says He Hopes Republicans Will Agree to Pass Legislation Restoring Roe, Might Actually Mean It". Slate. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Carney, Jordain (May 11, 2022). "Senate GOP, Manchin block abortion rights legislation". The Hill. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Garcia, Eric (May 11, 2022). "Sen Joe Manchin will vote against Democrats' abortion legislation but 'would vote for Roe v Wade codification'". The Independent. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Gomez, Patrick (January 7, 2021). "Facebook and Instagram (and Shopify) block Donald Trump indefinitely, Twitter keeps him on probation". The A.V. Club. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Neidig, Harper (December 20, 2018). "Senators lift hold on FCC commissioner". The Hill. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Cassata, Donna (October 3, 2017). "Senate confirms Trump choice Ajit Pai to head FCC". USA Today. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ McCarthy, Kieren (February 19, 2019). "US telcos' best pal – yes, the FCC – urged to dump its dodgy stats, crowd-source internet speeds direct from subscribers". The Register. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Kelly, Makena (March 4, 2021). "Senators call on FCC to quadruple base high-speed internet speeds". The Verge. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ McGill, Margaret (February 1, 2021). "Joe Manchin's bid to pierce tech's shield". Axios. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Brodkin, Jon (March 7, 2023). "Biden FCC nominee withdraws, blaming cable lobby and "unlimited dark money"". Ars Technica. Retrieved July 10, 2023.