Skating technique and influence of Johnny Weir

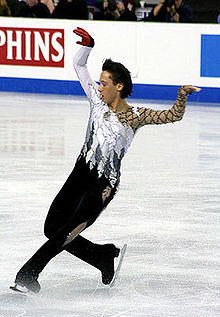

Figure skater and television commentator Johnny Weir is a two-time Olympian (2006 and 2010 Winter Olympics), the 2008 World bronze medalist, a two-time Grand Prix Final bronze medalist, the 2001 World Junior Champion, and a three-time U.S. National champion (2004–2006).

Weir had two coaches in his competitive figure skating career, Priscilla Hill, who was, unlike many figure skating coaches, was "nurturing and gentle"[1] and Russian Galina Zmievskaya, who had a different approach to coaching than Hill. Hill trained Weir in pair skating to strengthen his skating and to focus on skills other than jumps. Zmievskaya had a more Russian approach and focused on "drill sergeant-like demands for discipline and rigor".[2]

Weir considered his style of figure skating artistic and classical and was known for his lyricism. He believed that his style was "a hybrid of Russian and American skating",[3] which was brought out by hiring coaches from those countries and often caused conflicts with U.S. Figure Skating, as did many of his costume choices. He was instructed by Yuri Sergeev, a dancer for the St. Petersburg Ballet, taught himself the Russian language, conversing with Zmievskaya in Russian, and compared himself to Russian skater Evgeni Plushenko. In 2014, Weir designed Olympic gold medalist Yuzuru Hanyu's costume for his free skating program, worn during the Sochi Olympics.

Weir's outspokenness caused conflict between him and U.S. Figure Skating. Weir was praised for being one of the few figure skaters who spoke his mind, even when he knew it would get him in trouble with federation officials and judges. The press, especially in the U.S., made much out of the rivalry between Weir and his fellow competitor and rival, Evan Lysacek.

Coaching[edit]

Johnny Weir's first coach, Priscilla Hill, unlike many figure skating coaches, was "nurturing and gentle".[1] She became "a second mom" to him in Delaware.[4] At the beginning of Weir's career, "all [he] wanted to do was jump;[5] as sports writer Philip Hersh stated, jumping had always "come ridiculously easy to Weir".[6] Hill trained Weir in pair skating, teaming him with Jodi Rudden the first year they worked together, to focus on other aspects of figure skating, such as edges, spinning, footwork, and artistry. He and Rudden won a few minor competitions in pair skating the first two years he skated competitively. By 2005, Weir's skating skills were good enough that he did not need a quadruple jump to do well in competition, although he worked on adding it to his programs.[5][7]

In 2007, he changed coaches and hired Galina Zmievskaya, whom reporter Amy Strauss called "the polar opposite"[4] of Hill. He thought that he would benefit from Zmievskaya's "drill sergeant-like demands for discipline and rigor",[2] as well as her Russian approach to figure skating. She also focused on improving his jumps; Hill did not tend to focus on jumps in order to avoid stressing his body.[8] Zmievskaya made him practice his jumps over and over again, especially quadruple jumps. Before training with her, he had "a very free entrance"[8] into his triple Axel. He relied on his natural talent and would fly into his jumps, which made them exciting for him to perform and for the audience to watch. Zmievskaya had a strict pattern for how he accomplished his jumps, no matter how much it punished his body. He admitted in 2018, however, that quadruple jumps were his "nemesis".[9] Weir said that even though Zmievskaya was tougher than he was used to, she was also nurturing, caring for him, and controlling every aspect of his life. They developed a strong bond after a few weeks of working together.[10]

-

Weir's first coach, Priscilla Hill, in 2010

-

Weir and Zmievskaya during the 2008 Grand Prix Final

Artistry[edit]

Weir called his style classical. He was known for being "a very lyrical skater";[11] Olympic champion and commentator Dick Button described Weir as "more than just a jumper but an entertaining artisan".[12] Weir told figure skating reporter Lou Parees in 2004 that he believed that he was able to offset his technical weaknesses with his elegance. He did not think he needed to include quadruple jumps in his programs because he focused on other aspects of his skating. Parees said that Weir's landings were graceful and elegant, and that his spins were unique. At the time, Weir's secure landings earned him more points than skaters who attempted quadruple jumps and fell. He told Parees that "the softer edge" of his skating, which he did not need to practice, came naturally to him.[12] Weir told figure skating reporter Barry Mittan in 2005 that he thought the ISU Judging System, which was implemented in 2004,[13] benefited him because at the time, it rewarded every part of a skater's programs, especially Weir's strengths, such as "having good flow out of my jumps and having a different look on the ice”.[11]

Weir told Jeré Longman of The New York Times after the 2010 U.S. Nationals, "My obligation has always been to bring the artistic side of my sport out. Jumps are jumps, and everybody can do those jumps. But not everybody can show something wonderful and special and unique and different".[14] He also told Longman that he had no interest in making figure skating more "mainstream or masculine",[14] and that figure skating had a specific audience attracted to the sport's athleticism, theatricality, elegance, and artistry. Frank Carroll, who coached Weir's rival Evan Lysacek, said that he respected Weir for knowing who he was and for not caring what others thought of him.[14]

Weir believed that his style was "a hybrid of Russian and American skating",[3] two different approaches to figure skating. He said, in his 2011 autobiography Welcome to My World, "With coaches from both countries, I had married the artistic with the athletic, the passion with the technique. My costumes were different and so was the way I moved my body. I was an American boy with a Russian soul, and nobody else skated like me".[3] Weir developed a connection with Russia and with the Russian style of figure skating early in his career.[15] His first ballet teacher in Delaware, Yuri Sergeev, was a dancer for the St. Petersburg Ballet,[11][16] and he taught himself the Russian language, conversing with Zmievskaya in Russian.[17] He also studied czarist history and wore a jacket from the "old Soviet team uniform as a good-luck charm", given to him by Russian pairs skater and Olympic gold medalist Tatiana Totmianina, during the 2006 Olympics in Turin.[18] Weir compared his style to Russian champion Evgeni Plushenko, stating, "I think Plushenko is a very modern Russia, as it is now. I'm more from the Baryshnikov era".[19] This aspect of his skating style often caused conflicts with U.S. Figure Skating; Weir also said that his skating style, his programs, and costumes, especially his short program and accompanying costume he wore at his first Russian Grand Prix in 2002, was considered "an affront to American skating tradition".[18] Weir stated that his connection with Russia caused many Russian fans to "came to think of me as one of their own".[15] Figure skating reporter Gwen Knapp called Weir "an honorary Russian".[19]

Costumes[edit]

Weir often designed his own costumes or worked extensively with his designers. At times, his costume choices caused conflicts with U.S. Figure Skating, which he called "the federation".[20] In 2002, the first time he traveled to Russia for a competition, he was told by American skating officials that he had to change both his costume, which he had designed, and hairstyle, because they found them "too unique" and "disrespectful".[21] Weir's costumes helped him compete; like his music choices, they helped create his programs' mood and character. He stated, "I can't skate unless I feel beautiful",[22] so he spent a lot of time on his costume, hair, and makeup. In 2014, Weir designed Olympic gold medalist Yuzuru Hanyu's costume for his free skating program, worn during the Sochi Olympics.[23] In 2018, Hanyu paid tribute to Weir with his short program, as well as to Russian champion Evgeni Plushenko in his free skating program.[24]

Figure skater costume designer and Emmy-winner Jef Billings expressed his opinion that Weir's "singular personality" and "exaggerated style"[14] might have undercut Weir's skating. Phillip Hersh stated that earlier in Weir's career, he was able to maintain a balance between his "understated elegance" and "the too-too costumes he prefers", but by 2010, "the balance has tipped toward shtick".[14] In 2010, Weir designed fellow Olympian Yuzuru Hanyu's free skate costume.[25]

Influence[edit]

The haters have lost, they and all their floods of hate mail and death threats that flowed from the 2006 Olympics. The uncompromising Johnny Weir, on the verge of the culmination of his competitive career, has won. Among the world's best male skaters, Weir exhibits the most fluid poetry of motion, consciously elevating the sport's artistic elements over its purely athletic ones. But there has also been a powerful, tenacious, true grit that accounts for his success.

The 2006 Olympics marked the first time the wider world of sports enthusiasts encountered him, and many did not take kindly to his flamboyant, outspoken manner. Thus, when he didn't win a medal, the floodgates of hate issued forth. Not only Weir's perseverance, but a change in the mood of the country – reflected in the 2008 election – accounts for the fact that he's now seen as less freaking people out, and more entertaining and enlightening them with his wit and unapologetic uniqueness.

By simply being himself in such an open and high-profile way, he creates space for countless others to venture out with their own special individuality, and in doing this, he is making his best contribution of all.

Figure skating reporter Nicholas Benton, 2010, [26]

Weir's outspokenness often caused conflict between him and U.S. Figure Skating. In 2004, the federation told Hill to have Weir "tone down the skater's act" after he described the costume he wore during U.S. Nationals as "an icicle on crack".[6][27] Knapp called Weir "a natural with the media—smart, witty, insightful".[19] Steve Kelley of the Seattle Times called Weir "as much a world-class sportsman as he is a showman".[28] Kelley also called Weir "refreshing" in the "increasingly uptight" sport of figure skating, someone who celebrated his outlandishness and genuineness. He also stated, "While figure skating tries to become more mainstream and looks for some love from the NFL-loving fans, while it tries to 'masculinize' its sport, it shouldn't forget about athletic showmen like Johnny Weir. He is too good and too charismatic to be ignored".[28] The Associated Press (AP), prior to Weir's retirement in 2013, said that Weir had "always been delightfully refreshing, on and off the ice".[29] The AP praised Weir for being one of the few figure skaters who spoke his mind, even when he knew it would get him in trouble with federation officials and judges. They also said, "His colorfulness is part of his massive appeal, and he remains one of skating's most popular figures, particularly in Japan and Russia".[29]

The press made much of the rivalry between Weir and Evan Lysacek. E.M. Swift of Sports Illustrated wrote in 2007 that their rivalry was "exacerbated by Weir's increasingly outlandish behavior",[30][31] citing a recent photo shoot and Weir's fashion choices at press conferences during Nationals.[30] Nancy Armour of the AP reported during U.S. Nationals in 2007 that Lysacek and Weir had a "good rivalry"[32] that had developed over the previous few years. For five straight years, either Weir or Lysacek won gold at U.S. Nationals, Weir in 2004, 2005, and 2006, and Lysacek in 2007 and 2008, to the point that Weir called Nationals the "Evan and Johnny show".[33][34][35] Inevitably, Weir and Lysacek's skating styles and personalities were often compared. For example, Swift stated that even through they were evenly matched in their skating skills and abilities, they were "stylistic opposites".[36]

Swift compared Weir and Lysacek in this way: "Lysacek is all sparks of energy, emotion and gangly strength...Weir tries to embody elegance, style and fragile grace".[36] As for Weir and Lysacek themselves, they tended to downplay their rivalry.[37][38] In 2007, the Denver Post reported that although Weir and Lysacek were not friends, they were friendly, complimenting each other's skating, touring together in Champions on Ice, and avoiding speaking negatively about each other.[39] Also in 2007, Weir stated that the rivalry helped both he and Lysacek train and skate better, that it was exciting for the fans and for the skating community, and that it was good for U.S. men's figure skating.[38][37] By 2010, however, their rivalry intensified after Lysacek suggested that "a lack of talent" was the reason Weir was not hired to tour with Stars on Ice. Lysacek later apologized for his remarks.[40]

In 2021, Weir was inducted, along with professional figure skater and coach Sandy Schwomeyer Lamb and judge and official Gale Tanger, into the U.S. Figure Skating Hall of Fame. The inductions were postponed until the 2022 U.S. Figure Skating Championships due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[41]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Weir, p. 176

- ^ a b Benton, Nicholas F. (January 23, 2008). "Recharged Weir Determined to Take Back Skating Title". Falls Church News-Press. Falls Church, Virginia. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c Weir, p. 78

- ^ a b Strauss, Amy (December 20, 2007). "Sports: Johnny Drama". Philadelphia Magazine. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Hersh, Philip (January 13, 2005). "Weir Not Jumping at Skating's New Scoring System". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Hersh, Philip (March 21, 2004). "U.S. Champ Johnny Weir Doesn't Mind If He Upsets a Few Federation Officials; the 19-Year-Old Simply Wants to Have a Good Time". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Peterson, Anne M. (January 13, 2005). "Weir Took Wing Flying Solo". Spokesman Review. Associated Press. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Weir, p. 196

- ^ Lies, Elaine (January 4, 2018). "Figureskating-Quads: How Far Will They Go?". Reuters. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Weir, pp. 196—197

- ^ a b c "Johnny Weir: USA". Lausanne, Switzerland: International Skating Union. July 24, 2013. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Parees, Lou (June 21, 2004). "Johnny Weir: The Road to Russia". Golden Skate. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Thomson, Candus (February 1, 2006). "Revised System Born in Scandal". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Longman, Jeré (January 18, 2010). "The Difference Between Glitter and Gold for Johnny Weir". The New York Times. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Weir, p. 49

- ^ Weir, p. 29

- ^ Weir, p. 194

- ^ a b Weir, p. 54

- ^ a b c Knapp, Gwen (February 15, 2006). "Comrade in Arms: Skater Weir is American in Fact, a Russian in Heart". SF Gate. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Weir, p. 8

- ^ Weir, p. 53

- ^ Weir, p. 52

- ^ Gaines, Cork (February 14, 2014). "Figure Skater Wins Gold Wearing A Costume Designed By Johnny Weir". Business Insider. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Kwong, PJ (September 22, 2018). "The Evolution of Yuzuru Hanyu: How One of the Best Ever Keeps Developing". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Sports. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Flade, Tatjana (April 21, 2011). "Hanyu Shoots for the Top". Golden Skate. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Benton, Nicholas F. (February 17, 2010). "Johnny Weir Has Prevailed". Falls Church News-Press. Falls Church, Virginia. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Weir, pp. 66—67

- ^ a b Kelley, Steve (January 16, 2010). "Figure Skating's Flamboyant Johnny Weir Must be Taken Seriously". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Skater Johnny Weir out of Sochi". ESPN. Associated Press. September 17, 2013. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Swift, E.M. (January 29, 2007). "Something Special". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ "2007 US Figure Skating Championships: Men's Highlights". Golden Skate. January 30, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Armour, Nancy (January 25, 2007). "Weir, Lysacek Rivalry Heats up Today". Arizona Daily Star. Tucson, Arizona. Associated Press. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ "Johnny Weir 2005/2006". International Skating Union. March 23, 2006. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ "Evan Lysacek 2006/2007". International Skating Union. Archived from the original on July 2, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Macur, Juliet (January 23, 2009). "Weir and Lysacek Find Company at the Top". The New York Times. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Fit to be Tied: Scoring Anomaly Spices up Lysacek-Weir U.S. Rivalry". Sports Illustrated. January 27, 2008. Archived from the original on January 31, 2008. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Men's Skating Needs This Rivalry of Weir-Lysacek". The Seattle Times. January 26, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "Rivalry between Weir-Lysacek Gives US Skating Some Buzz". Pioneer Press. St. Paul, Minnesota. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Henderson, John (January 24, 2007). "Weir, Lysacek Rule Landscape". The Denver Post. Denver, Colorado. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Benet, Lorenzo; Dyball, Rennie (April 30, 2010). "Inside Story: Evan Lysacek and Johnny Weir 'At War'". People. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ "Johnny Weir, Sandy Schwomeyer Lamb, Gale Tanger make U.S. Figure Skating Hall of Fame". ESPN. Associated Press. December 28, 2020. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

Works cited[edit]

- Weir, Johnny (2011). Welcome to My World. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4516-1028-4.