Tom Drury

Tom Drury | |

|---|---|

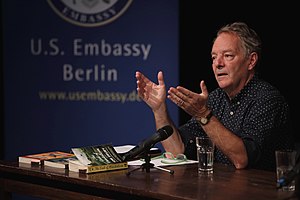

Tom Drury opens the 2017 U.S. Embassy Literature Series at English Theatre Berlin. | |

| Born | 1956 (age 67–68) Iowa, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | University of Iowa (BA) Brown University (MFA) |

| Genre | Literary fiction |

| Notable works | The End of Vandalism |

| Notable awards | Guggenheim Fellowship, Berlin Prize |

| Website | |

| www | |

Tom Drury (born 1956) is an American novelist and the author of The End of Vandalism. He was included in the 1996 Granta issue of "The Best of Young American Novelists"[1] and has received the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Berlin Prize, and the MacDowell Fellowship. His short stories have been serialized in The New Yorker[2] and his essays have appeared in The New York Times Magazine, Harper's Magazine, North American Review, and Mississippi Review.

His fiction, set in the American midwest, has been described by The Guardian as having "a kind of dislocation; a 1950s or 60s sensibility dropped into a 90s social landscape."[3] In 2015, The Guardian called him "an overlooked giant of American comic fiction."[4] The Independent compared him to Jonathan Franzen, Dave Eggers and David Foster Wallace, and called him "the greatest writer you've never heard of . . . a cult figure, the new Richard Yates", writing: "His anonymity is a literary tragedy."[5]

He has taught writing at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, Yale University, Wesleyan University, Florida State University, and La Salle University.

Background and education[edit]

Drury was born in Iowa, in 1956, and grew up in Swaledale. He received his bachelor's degree in journalism from the University of Iowa in 1980[6] and his MFA in creative writing at Brown University in 1987, where he studied with Robert Coover.[7]

Career[edit]

Journalism[edit]

Drury worked at the Danbury News-Times, the Litchfield County Times, and The Providence Journal. He was an editor at Tampa Bay Times.[8]

Literary career[edit]

Excerpts of Drury's first novel, The End of Vandalism, appeared in The New Yorker before it was published in 1994 by Houghton Mifflin.[9] The book was an ALA Notable Book in 1995.

His second novel The Black Brook (1998) was described by Kirkus Reviews as "edgy, captivating" and "an irresistibly droll portrayal of an All-American liar, loser, and innocent."[10] On his third novel Hunts in Dreams (2000), Salon.com wrote: "Drury is in love with the quotidian in a way that's specific to a few writers, painters and filmmakers. You can feel the pleasure he takes in precisely describing unremarkable events and objects -- cutting lumber ("Sawdust flew in furry arcs that coated their arms and necks"), a wooden coat hanger ("The arms were curved and smooth, and the bottom rail was chamfered in with Phillips-head screws")."[11]

His fourth novel The Driftless Area (2006) was adapted into a film starring Aubrey Plaza, Frank Langella, Anton Yelchin, Zooey Deschanel, John Hawkes, Ciaran Hinds, and Alia Shawkat.[12]

Drury's fifth novel Pacific (2013) features characters from The End of Vandalism and Hunts in Dreams and is also set in the fictional Grouse County. The three books have been called a series. In a review, NPR called it a "novel you read to linger in the moment", adding: "But to call Pacific a sequel implies that you need to read the first two installments to fully invest in this slight, beguiling third. You don't. Plot takes a back seat to sharp observations and deadpan wit in Drury's work, and Pacific can easily stand alone."[13]

About setting his novels in the midwest, he told The New York Times in 2013:

I go back to a very specific aspect of the Midwest — small towns surrounded by farmland. They make a good stage for what I like to write about, i.e., roads and houses, bridges and rivers and weather and woods, and people to whom strange or interesting things happen, causing problems they must overcome. Once I understood I was free to use the setting as a stage — to bring in elements from Vermont, say, or Key West, or anywhere — and that my version of the Midwest would not be obliged to represent the actual Midwest, then it seemed like the place offered all the freedom I needed, with the added benefit of being well remembered.[14]

Drury's work has gained a following among fellow writers. The novelist Daniel Handler claimed The Black Brook as the book he reread the most.[15] In a piece for The Guardian, writers Yiyun Li and Jon McGregor wrote:

Drury’s rare achievement is to populate a novel with a group of life-sized nobodies. How does he do this? By abandoning both tragedy and comedy, in the recognition that life’s damages are often done and felt in the least dramatic ways, and absurdity results from people’s efforts to be honest or serious.[16]

Awards and honors[edit]

- Granta's Best Young American Novelists

- Best of BBC Radio’s Recent Short Fiction, “Heroin Man”

- John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellow

- ALA Notable Books, The End of Vandalism

- GQ‘s Best Books of Last 45 Years, The End of Vandalism

- New York Magazine Best Books, The End of Vandalism

- Publishers Weekly Best Books, The End of Vandalism

- Borders Original Voices, The Black Brook

- New York Times Notable Books, Hunts in Dreams

- New York Times Editor’s Choice, The Driftless Area

- Chicago Tribune Best Books, The Driftless Area

- San Francisco Chronicle Best Books, The Driftless Area

- MacDowell Fellowship

- National Book Awards Longlist, Pacific

- New York Times Editors' Choice, Pacific

- San Francisco Chronicle Recommended Books, Pacific

- Berlin Prize Fellowship[17][18]

Bibliography[edit]

- In Our state (1989)

- The End of Vandalism (1994)

- The Black Brook (1998)

- Hunts in Dreams (2000)

- The Driftless Area (2006)

- Pacific (2013)

References[edit]

- ^ "Best of Young American Novelists". Granta Magazine (54). Granta Publications. Summer 1996.

- ^ "Tom Drury Latest Articles". The New Yorker. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ McGregor, Jon, and Yiyun Li (6 November 2015). "In praise of Tom Drury's small-town America". The Guardian. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ Lawson, Mark (28 November 2015). "Pacific by Tom Drury review – an overlooked giant of American comic fiction". The Guardian. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ Kidd, James (17 April 2015). "Why does Tom Drury remain the greatest writer you've never heard of?". The Independent. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ "PW: Tom Drury: American Strains of Humor". Publishers Weekly. 2000-05-22. Archived from the original on 2012-09-28. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

- ^ Kidd, James (17 April 2015). "Why does Tom Drury remain the greatest writer you've never heard of?". The Independent. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ "Florida Writers' Festival, Spring 2003". English.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

- ^ "Author Tom Drury to Visit Gustavus Adolphus College - Posted on September 20th, 2006 by News Office". Gustavus Adolphus College. 2006-09-20. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

- ^ "THE BLACK BROOK". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ Seligman, Craig (3 May 2000). ""Hunts in Dreams" by Tom Drury". Salon. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (8 May 2014). "Cannes: Frank Langella Joins 'The Driftless Area'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ Reese, Jennifer. "West Meets Midwest In Tom Drury's Quirky 'Pacific'". NPR. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ Williams, John (13 June 2013). "Back to Grouse County: Tom Drury Talks About 'Pacific'". The New York Times. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ Handler, Daniel (29 August 2017). "Daniel Handler: Maybe I'll Start a Dive Bar Proust Club". Literary Hub. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ McGregor, Jon, and Yiyun Li (6 November 2015). "In praise of Tom Drury's small-town America". The Guardian. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ "Tom Drury". Grove Atlantic. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ "About". tomdrury. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- 1956 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American novelists

- Novelists from Iowa

- University of Iowa alumni

- Brown University alumni

- Iowa Writers' Workshop alumni

- American male journalists

- 21st-century American novelists

- American male novelists

- American male short story writers

- 20th-century American short story writers

- 21st-century American short story writers

- 20th-century American male writers

- 21st-century American male writers

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers