User:Andrzejbanas/sandbox

| Dracula | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Tod Browning |

| Based on | and the 1927 stageplay by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston |

| Produced by | Carl Laemmle, Jr.[2] |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Karl Freund |

| Edited by | Milton Carruth[2] |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures Corp. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 75 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States[3] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $341,000 |

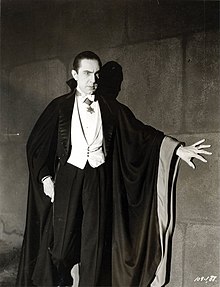

Dracula is a 1931 American horror film directed by Tod Browning. It is based on both the novel Dracula by Bram Stoker and the 1927 play Dracula. The film stars Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula, a vampire who emigrates from Transylvania to England and preys upon the blood of living victims, including Mina Seward, the fiancée of John Harker. Dracula was produced by the Universal Pictures Corp., who was interested in purchasing the rights for a film adaptation of the story as early as June 1915. After Carl Laemmle, Jr. became in charge of the production activity at Universal, he began changing the policy on the development of film production leading to purchase of the rights to both the novel and the popular play. A screenplay was adapted and went through at least four drafts from various writers ranging from Fritz Stephani, Louis Bromfield, Dudley Murphy and Garrett Fort . Their films script includes original material and adapt parts of the novel, play, as well as elements from the previous Dracula adaptation, Nosferatu (1922). Some of the cast was brought in from the play such as Edward Van Sloan and Herbert Bunston while the role of Count Dracula went through several potential cast including Paul Muni, John Wray before deciding on Bela Lugosi.

Plot[edit]

Renfield is a solicitor traveling to Count Dracula's castle in Transylvania on a business matter. The local village people fear that vampires inhabit the castle and warn Renfield not to go there. Renfield ignores their warnings, and asks his carriage driver to take him to the Borgo Pass. Renfield is driven to the castle by Dracula's coach, with Dracula disguised as the driver. On arrival to the castle, Renfield enters the castle and is welcomed by the Count, who, unbeknownst to Renfield, is a vampire. They discuss Dracula's intention to lease Carfax Abbey in England, where he intends to travel the next day. Dracula hypnotizes Renfield into opening a window. Renfield faints as a bat appears, and Dracula's three wives close in on him. Dracula waves them away, then attacks Renfield himself.

Aboard the schooner Vesta, Renfield is a raving lunatic slave to Dracula, who hides in a coffin and feeds on the ship's crew. When the ship reaches England, Renfield is discovered to be the only living person. Renfield is sent to Dr. Seward's sanatorium adjoining Carfax Abbey. At a London theatre, Dracula meets Seward. Seward introduces his daughter Mina, her fiancé John Harker, and a family friend, Lucy Weston. Lucy is fascinated by Count Dracula. That night, Dracula enters her room and feasts on her blood while she sleeps. Lucy dies the next day after a string of blood transfusions. Renfield is obsessed with eating flies and spiders. Professor Van Helsing analyzes Renfield's blood and discovers his obsession. He starts talking about vampires, and that afternoon Renfield begs Seward to send him away, claiming his nightly cries may disturb Mina's dreams. When Dracula calls Renfield through the medium of a wolf howling, Renfield is disturbed by Van Helsing showing him wolfsbane, which Van Helsing says is used for protection from vampires.

Dracula visits Mina, asleep in her bedroom, and bites her. The next evening, Dracula enters for a visit, and Van Helsing and Harker notice that he does not have a mirror reflection. When Van Helsing reveals this to Dracula, he smashes the mirror and leaves. Van Helsing deduces that Dracula is the vampire behind the recent tragedies. Mina leaves her room and runs to Dracula in the garden, where he attacks her. The maid finds her. Newspapers report that a woman in white is luring children from the park and biting them. Mina recognizes the lady as Lucy, risen as a vampire. Harker wants to take Mina to London for safety but is convinced to leave Mina with Van Helsing. Van Helsing orders Nurse Briggs to take care of Mina when she sleeps and not to remove the wreath of wolfsbane from her neck.

Renfield escapes from his cell and listens to the men discussing vampires. Before his attendant takes Renfield back to his cell, Renfield relates to them how Dracula convinced Renfield to allow him to enter the sanatorium by promising him thousands of rats full of blood and life. Dracula enters the Seward parlor and talks with Van Helsing. Dracula states that Mina now belongs to him and warns Van Helsing to return to his home country. Van Helsing swears to excavate Carfax Abbey and destroy Dracula. Dracula attempts to hypnotize Van Helsing, but the latter's resolve proves stronger. As Dracula lunges at Van Helsing, he draws a crucifix from his coat, forcing Dracula to retreat. Harker visits Mina on a terrace, and she speaks of how much she loves "nights and fogs." A bat flies above them and squeaks to Mina. She then attacks Harker, but Van Helsing and Seward save him. Mina confesses what Dracula has done to her and tells Harker their love is finished. Dracula hypnotizes Briggs into removing the wolfsbane from Mina's neck and opening the windows. Van Helsing and Harker see Renfield heading for Carfax Abbey. They see Dracula with Mina in the Abbey. When Harker shouts to Mina, Dracula thinks Renfield has led them there and kills him. Dracula is hunted by Van Helsing and Harker, who know that Dracula is forced to sleep in his coffin during daylight, and the sun is rising. Van Helsing prepares a wooden stake while Harker searches for Mina. Van Helsing impales Dracula through the heart, killing him, and Mina returns to normal.

Cast[edit]

Cast sourced from the book Universal Horrors.[2]

- Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula

- Helen Chandler as Mina Seward

- David Manners as John Harker

- Dwight Frye as Renfield

- Edward Van Sloan as Prof. Van Helsing

- Herbert Bunston as Dr. Seward

- Frances Dade as Lucy Weston

- Joan Standing as Maid

- Charles K. Gerrard as Martin

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Background[edit]

Dracula is based on the novel Dracula written in 1987 by Bram Stoker.[2] The original novel is written epistolary style with chapters comrised of different personal letters, diary entries, ship's logs, and newspaper accounts and phonograph diaries.[2] The book was previously adapted from the novel as the 1922 German production titled Nosferatu directed by F. W. Murnau.[4] The film only made a brief appearance in the United States in 1929 in New York and Newark.[5] This version was an unofficial adaptation of the novel with characters names changed.[4] As the adaptation was unauthorized, Stoker's estate sued and sought to have all prints of the film destroyed.[4][5] Two years later, the British producer Hamilton Deane premiered a stage version of Dracula at the Grand Theatre in Derby, England.[4] This version of the play was a modernized retelling of Stoker's story.[4] The play's success led to Deane taking it on tour for the next three years.[4] The play opened in London's Little Theatre on February 14, 1927 where it was sold well while not being critically well received.[4] After seeing the play in London, American producer Horace Liveright bought the rights to the for Broadway, and hired John L. Balderston to Americanize the Deane's text.[4][6] The Broadway version featured actors who would later be cast into the Universal film, including Bela Lugosi as Dracula, Edward Van Sloan as Prof. Van Helsing, Herbert Bunston as Dr. Seward.[2][4] Dracula opened at New York's Fulton Theatre on October 5, 1927 where it ran for 265 performances finally closing in New York in May 1928.[4] Gary Don Rhodes described the play as "taking America storm", a statement backed up by a 1930 article in the Chicago Tribune claiming that the play "has been rolling around the country ever since its first vogue two or three seasons ago, coaxing money into box offices that had abandoned hope of the drama, and of the shriek-and-shudder plays of the last five years it easily leads the list."[7][8]

Universal Pictures had been interested in adapting Dracula as early as June 1915.[9] In June, the studio looked into adapting the novel but determined that the rights might involve complicated litigation.[9] The Oakland Tribune reported in 1920 that director Tod Browning was rumoured to want to produce Dracula as a film.[9] Nothing was developed beyond this article for a film adaptation in 1920.[9] A report from 1925 suggested that Carl Laemmle, Sr., the founder and head of Universal Pictures, may develop Dracula with Arthur Edmund Carew potentially in the title role.[9] Office communication notices noted disagreements on purchasing the rights to adapt the film due to censorship issues.[4] During the late 1920s, Carl Laemmle, Jr. was the only son of Laemmle, Sr. who followed his father's work in the film industry.[10] Laemmle Sr. let his son produce the Paul Fejos' Lonesome (1928) and by the end of that year, Laemmle Jr. was promoted to Associate Producer, leading him to supervise Fejos' The Last Performance (1928) and Paul Leni's The Last Warning (1927).[11] By May 1929, the Film Daily reported that Laemmle Jr. was "in complete charge of [Universal] and all production activity. The change is effective at once."[12] In 1929 negotiations for the screen rights to Dracula began among different parties.[13] A representative of Bram Stoker's widow began working to offer the rights to several studios, including Columbia Pictures, Pathé, Paramount Pictures, MGM, and Universal.[13]

In 1930, Laemmele Jr. made a major policy change for the studio to "discontinue program pictures and just make only great pictures."[14][15] While Universal was focused on these films, Universal limited the cost of their bigger budget productions, spending roughly $500,000 on each of its twenty planned productions which was later lowered to budgets ranging from $350,000 to $400,000.[16] By May 3, 1930, Universal reported a net loss of over $575,000 and was putting in cost-cutting measures including losing as many as 50 employees.[16] This led to non-production based employees in the upper ranks of the studio to build a smaller number of experienced executives.[17] The studio officially purchased the rights to both the play and the novel Dracula in June 1930 for $40,000.[4] Universal purchased the rights to three different versions of the play.[18]

Scripting[edit]

Dracula's screenplay draws from both the novel Dracula by Bram Stoker and the 1927 stageplay by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston[2] From June to late September 1930, the film's screenplay went through at least five different authors who attempted to adapt Dracula.[4][19] Rhodes stated that a complete history of the adaptation of the film to the screen cannot be constructed, it is still possible to learn specific details on how the film changed from surviving archival material.[19] The first person who had seemed to write a treatment of Dracula was Fritz Stephani in 1930.[20] Stephani's treatment starts with the story in England before Harker departs to Hungary. This element of the story is not in either the play or the original novel and appears to have potentially been an original idea or borrowed from Murnau's Nosferatu which opens similarly.[20] Stephani's script had other similarities to Nosferatu, such as doors in Castle Dracula opening on their own and the vampire seeing an image of a young male lead's fiancee, leading him to remark that she had a "lovely neck."[21] Elements of Stephani's screenplay that are included in the final film that were not part of either the novel or the play. These include include Harker looking out of his carriage and seeing a bat flying in front of the carriage with no human driver and Van Helsing murdering Dracula.[22] Variety announced that on July 9, 1930 that Louis Bromfield had arrived that week to being work on the screen treatment for Dracula.[23] At that time, Bromfield was one of the most famous contemporary American authors with his books being best-sellers. From personal letters from the author himself, he may have been working on Dracula earlier than this, stating in a mid-July letter to a friend that he had been working on the film for five months.[23] The Hollywood Filmograph reported that Laemmle, Jr. specifically chose Bromfield after reading his novel Early Autumn (1926).[23][24] Observing his treatment titled First Treatment for Dracula dated July 18, 1930, Bromfield borrowed far more from the novel than the play.[25] Bromfield's script also included elements that would be included in the final script, including Dracula's castle doors opening on its own, Dracula and three vampire women sleeping in coffins at the bottom of the castle, but was otherwise mostly discarded.[26]

On August 24 the New York Times reported that Bromfield and Dudley Murphy would collaborate on the dialogue for Dracula.[27] Whether the two actively worked together or if Murphy worked in isolation updating Bromfield's script is unknown.[26] Murphy had previously worked in the film industry shooting avant-garde projects such as Soul of the Cypress (1920) and Ballet mécanique (1924).[28] From the surviving pages of their script titled Dracula by Louis Bromfield and Dudley Murphy incorporates the term "Nosferatu", which was in neither the play or novel.[29] Elements of their script that are included in the final film include, such as Harker's arrival in Transylvania.[30] Their script is partially lost and ends when Dracula offers Harker dinner and wine early in the script.[31]

Garrett Fort was previously an employee at Famous Players studio and from there worked as a writer under contract with Cecil B. DeMille and later at Paramount.[32] He began developing a reputation as an important screenwriter of talkie films, with the Film Daily describing him On February 24, 1930 as "rapidly earning the title of 'The Edgar Wallace of the Movies,' judging by the way in which he is turning out scripts and originals that sell."[33] Fort was signed March 18, 1930 to Universal for a long term contract.[34] On September 15, Film Daily reported Fort as having signed a contract on September 11, 1930 for the role of Count Dracula.[35] On August 23, 1930 Fort published an advertisement in the Hollywood Filmograph that announced he was doing the adaptation and dialogue for Dracula, one day before the New York Times reported the Murphy and Bromfield collaboration.[36] The final shooting script dated September 26, 1930 was credited "Adaptation and Dialogue by Tod Browning and Garrett Fort" and "Continuity by Dudley Murphy".[37] In contrast John LeRoy Johnston's early draft of the Dracula pressbook credited Murphy for "added dialogue" opposed to continuity.[37] Fort received the sole screen credit.[4] The screenplay was close to the American version of the play with some lines of dialogue being lifted from the novel that were not in either form of the plays.[4] The title page of the fourth draft of the final script that was dated September 26, 1930 splits the credits between Fort and Browning.[4]

Pre-production[edit]

Crew[edit]

Browning had begun work behind film cameras with his film The Lucky Transfer (1915) and joined Universal in 1919.[38][39] Browning worked at Universal making Outside the Law (1920) starring Lon Chaney, Sr..[40] The film was among the film was the most in demand film than any other the studio had produced, leading to its reissue in 1926.[40] Browning would continue to work with Chaney up until the film West of Zanzibar (1928), their tenth and final collaboration.[41] Browning was announced for several productions in 1930 at Universal including a sound version of Virgin of Stamboul, The Scarlet Triangle and Little Buddha and a sound remake of Outside the Law.[42] On July 3, 1930 the Hollywood Daily Citizen announced that Laemmle Jr. had "pointed the finger at Tod Browning to direct Universal's all-talking version of Dracula, after having seen with great satisfaction the proof [of] the director's talents in the nearly finished Outside the Law (1930)."[43] The key personnel involved with Dracula, specifically the director, screenwriters, cinematographer, producer and assistant director all died before any historian conducted any serious interviews with them regarding the production.[44] The same is true except for one cast member: David Manners. In an interview published in 1974, Manners spoke that Browning was "always off to the side somewhere" and that he remembered being "directed by Karl Freund [...] I believe he is the one mainly responsible for making Dracula watchable today."[45] In his book The Monster Show, Skal applied Manner's statements to have him conclude that Freund had directed large amounts of the film.[46] This included the concert hall sequences, the chase and destruction of cellars in Carfax Abbey.[46] Skal noted that as other actors were no longer alive, it could not be figured how much Browning did or did not direct while finding that that Manners statements corroborated with the Hollywood Filmograph's statements later that "we cannot believe that the same man was responsible for both the first and latter parts of the picture."[46] Rhodes interviewed Manners in 1985 who echoed similar statements to his 1974 interview, as well as stating he did not particularly enjoy the company of Browning and Lugosi.[45] Rhodes has challenged Manners and Skal's assertations in 2014, stating that Manners, given his role and script, he would only have been on set for no more than half the shoot.[47] Rhodes has noted that several Manner's memories of the production have been proven incorrect ranging from his memories of his pay.[47] Contemporary interviews of the period involving actors and the director refer to only Browning directing, such as an interview with the Hollywood Filmograph with Lugosi specifically stating how Browning told him how to act for screen opposed to stage.[48] Rhodes continued noting that Browning's style of direction often was with little instruction and that he would only discuss with actors their performance he felt it was needed.[49] Carla Laemmle who appears only in the opening carriage ride scene stated in 2012 she had no memory of Browning and when asked about him again in 2014, she responded that she had a vague memory of meeting him briefly.[50]

The films director of photography was the famous German cinematographer Karl Freund. Freund had previously shot films ranging from The Golem (1915), The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920), Murnau's The Last Laugh (1924) and Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927).[51] According to an article in American Cinematographer, Freund had come to Hollywood to work for Technicolor, but when his work arrangements with them fell through he signed on with Universal in 1930.[52] The Hollywood Filmograph reported on September 27, 1930 that cinematographer for Dracula was unassigned. Variety only announced Freund as the films cinematographer until October 4, 1930, by that time the film had already been in production for five days.[51] Freund left no accounts on his work on Dracula.[53] The film's art director was Charles D. Hall who had previous work designing sets for films such as Charlie Chaplin's The Gold Rush (1925) before working at Universal.[51] Among the crew working under Hall, was Herman Rosse who had won an academy ward for his work as the art director on Universal's King of Jazz (1930).[54] Rosse reportedly saved some of the set design budget for Universal working on the film, by designing the facade of Castle Dracula which was pieced together from portions of disassembled Medieval sets from the silent era.[55] Jack Pierce had signed a two year contract with Universal on February 19, 1929.[54] Pierce had already worked on The Cat Creeps (1930) for Universal would continue to work on several of their horror projects in the 1930s and 1940s.[54]

Casting[edit]

Universal's casting director Phil Friedman had taken over from Harry Garson in February 1930 after Garson was promoted to a producer.[56] Friedman underwent an operation for appendicitis in late September 1930.[57] He was involved with casting at least two key members of the cast: Dwight Frye and Edward Van Sloan.[58] Frye was announced to have been cast by The Hollywood Reporter on September 9 while Van Sloan was announced by Variety on September 10.[59][60] Van Sloan was specifically cast for his association with the play, as Universal wanted to further connect their film adaptation to the successful play.[58] The same Variety article noted that other principal parts, including the the role of Dracula have not been completed.[60]

Lew Ayres, who starred in All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) was initially announced on September 23 to be playing the role of Jonathan Harker. As the script changed and reduced the role of Harker in the film, Laemmle Jr. opted to not cast Ayres.[61] The Hollywood Reporter announced on September 12, 1930 that Jeanette Loff was preparing for her work in Dracula. Loff was a relatively big name actress in 1930, with The Hollywood Reporter referring to her as one of Universal's "Box Office Leaders" in 1930.[62] In September, Loff began fighting for a contract release that was granted by Universal leading her to be signed with Tiffany Pictures.[63] On September 24, Helen Chandler was announced for Dracula, where she was loaned out from Warner Bros. immediately after signing a contract with the company.[63]

Bela Lugosi was not the initial choice for the role of Dracula.[64] In his book Hollywood Gothic, David J. Skal spoke that Universal had not been interested in Lugosi for the role based on a telegram from March 27, 1930 from Laemmle Jr. that stated "Not Interested Bela Luogsi Present Time".[65][35] Rhodes countered this stating the telegram makes no mention of Dracula specifically and that Universal had not even purchased the rights to the film yet at the time.[66] It has been reported that Universal's initial choice was that of Lon Chaney, Sr. who was struck with bronchial cancer.[64] Chaney died of the disease on August 26, 1930.[64] Rhodes declared that this was not quite true as Chaney was never cast as Count Dracula while Browning would have wanted him for the film.[67] Michael Francis Blake, who wrote three books about Chaney, stated that it would be quite unlikely that Chaney would have been in Dracula due to his star status at MGM, and that he was having new success at at talking pictures.[68] Browning spoke in July 1930 that his idea of casting for Dracula "getting a stranger from Europe, and not giving his name. It takes away from the thrilling effects of the story."[69]

On June 21, Universal announced that John Wray had been cast as Dracula.[64] Wray had previously been in Universal's All Quiet on the Western Front (1930).[64] Wray did not get the part.[64] Rumors began circling in In late June 1930 that Bela Lugosi would star as Dracula.[69] On August 11, 1930, the films associate producer E. M. Asher contacted director Roland West about the availability of Chester Morris who had starred in West's The Bat Whispers which was not yet released at the time.[70] West had turned down Asher's offer, stating on August 12 that he was trying to find a romantic story for the actor.[71] By late August, Paul Muni was being considered and Universal had shot screentest with William Courtenay.[64][71] Joseph Schildkraut and John Carradine claimed later in their careers that they were considered for the role of Dracula but there is no evidence of them being seriously considered for the role by Laemmle, Jr.[72]

Filming[edit]

In late August 1930, Universal announced that Dracula would begin production in the next three weeks.[73] Early proposed start dates included September 22 and September 25 while filming would not officially start until September 29, 1930.[74] Universal allotted for a budget of $355,050 for Dracula which was an A-picture budget for their productions and had a shooting schedule of 36 days.[64] Dracula was made during the latter period of the silent to sound film period of cinema.[75] Beginning in 1928, the preferred approach to developing films for foreign-language markets was to produce more than one version of some films.[76] These versions used the same scripts, sets, and costumes as the English-language original but employed different actors who could speak languages such as Spanish, French and German.[76] Universal Pictures was one of the first studios in Hollywood to produce foreign-language films and in September 1930, announced that their 1930-1931 seasons would include a dozen of these films.[77] On September 23, Universal announced that Dracula would get it's own Spanish language version.[78] While Skal had reported the film had been shot sequentially, shooting schedules show that the film was shot by location, with the exception of the Transylvanian sequences.[79] On September 29, 1930, Browning shot the interiors and exteriors at the Inn.[79] The next day shots of the interior coach that takes Renfield to the Inn and the Inn's courtyard were shot on a hill in the Universal backlot.[79] Once filming began, Browning made numerous changes to the shooting script.[50] Changes to the final shooting script was a removal of a character in the carriage, mild dialogue changes, and a scene where the proprietor of the inn is in discussion.[50]

Film continued between October 1st through the 4th, with filming of Dracula's Castle and Borgo Pass which used the mountainous area on the West side of the Universal lot.[80] Browning again made changes to conversation between Dracula and Renfield.[81] Rhodes noted the greatest change was what happened to Renfield, which initially involved him lookout a window and seeing the height of a castle above a dark chasm. He then sees a bat which makes him hit the window in shock to fall to the floor unconscious.[81]

The film completed shooting on November 15, an additional six days over what was originally scheduled.[64] Re-takes were made on January 2, 1931 with a final budget for the film being $341,191.20.[64]

Post-production[edit]

Music[edit]

As was common in early sound film, there is little music in Dracula.[82] Music is heard during the main title with a brief interlude at the opera and ringing of bells as Mina and Harker leave Carfax Abbey.[82] In 1999, Universal created new edition of Dracula with a Dolby Digital 5.1 score composed and conducted by classical music composer Phillip Glass.[83]

Weaver, Brunas and Brunas noted the new film was greeted with mixed reception.[83]

Release[edit]

Marketing[edit]

In 1930s, the mystery film genre was in vogue and early information on Dracula being promoted as mystery film was common.[18] The idea that the film being a mystery story persisted despite the novel, play and film's story relying on the supernatural.[18] Laemmle Jr. and Browning reported discussed for a week on whether Dracula should "be a thriller or a romance" before agreeing to "make it both".[84] Many years later, Laemmle Jr. spoke in an interview with film historian Rick Atkins that they "decided to hype it as both, and I've never regretted it."[85] Rhodes explained that this type of promotion existed yet as the idea of the horror film did not exist yet as a codified genre and although critics have used the term "horror" to describe films in reviews, the term has not truly be developed at the period as the genre's name.[85]

The film's poster campaign was overseen by Universal advertising art director Karoly Grosz, who also illustrated the "insert" poster himself.[86] Original posters from the 1931 release are scarce and highly valuable to collectors. In 2009, actor Nicolas Cage auctioned off his collection of vintage film posters, which included an original "Style F" one sheet that sold for $310,700; as of March 2012, it stood as the sixth-highest price for a film poster.[87] In December 2017, a "Style A" poster — one of only two known copies — sold at auction for $525,000, setting a new world record for the most expensive film poster.[88]

Theatrical release[edit]

Dracula premiered on February 12, 1931 at the Roxy Theatre in New York.[89] where it was distributed by Universal Pictures.[2][3]

Box office[edit]

Home media[edit]

Critical reception[edit]

Weaver, Brunas and Brunas described the contemporary reviews of Dracula "uniformly positive, some even laudatory" and was "one of the best received critically of any of the Universal horror pictures."[82]

Audience reception[edit]

Aftermath and influence[edit]

Sequels and follow-ups[edit]

Within three weeks of the release of Dracula, Universal considered no fewer than three ideas for a sequel.[90] These included the following titles submitted to the Hayes Office: The Modern Dracula, The Return of Dracula and The Son of Dracula.[90] None of these films were produced and no info on their potential plot lines are available.[91][92] Film historians have described in different terms to what films belong to the series. Ken Hanke wrote in A Critical Guide to Horror Film Series stated that Universal produced only three films (Dracula, Dracula's Daughter, and Son of Dracula) "can properly be called part of a loosely grouped Dracula series" and that Son of Dracula, is really a distant cousin.[93] Rhodes wrote in his book Tod Browning's Dracula that Universal had produced five films in their classic era whose plotlines assume the audience would be familiar with the Count Dracula character from either viewing or being aware of the 1931 film while Hanke includes both Daughter of Dracula and Son of Dracula.[94][93] Hanke commented that The House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula merely featured Dracula in "token appearances" and were more incorporated into Universal's Frankenstein series.[93] Rhodes commented on the House of films as being very distant from the others, with Dracula being portrayed differently: as a Southern gentleman with a moustache and that the character only limited appearances in the films, such as his character only appearing for 15 minutes in The House of Frankenstein.[95][91]

Dracula's Daughter featured more of the original crew of the first film than any subsequent sequel.[96] This included Balderston of the Deane-Balderston team who co-authored the 1927 Broadway play of Dracula, Fort who was the co-author of the final shooting script to Dracula, and E. M. "efe" Asher, who was the associate producer on Dracula.[96] Universal originally planned to have Lugosi reprise his role in Dracula's Daughter, the final script did not feature his character outside a prop corpse while Sloan returned as Van Helsing, who is renamed Von Helsing in the film.[97] In 1939, Lugosi's friend Manly P. Hall wrote a treatment for an unmade sequel to Dracula that would follow-up after the end of the 1931 film.[91] This film involved Dracula returning back to life as Van Helsing, who had staked the vampire one minute after sundown, an event that would rework the events of the original film.[91] In 1949, Universal discussed the idea of a remake of Dracula with Lugosi with an industry press claiming the deal was in "negotiation stages".[91] Prior to the release of House of Dracula, an April 1944 Hollywood trade paper announced a film titled Wolfman vs. Dracula that was to have been directed and produced by Ford Beebe.[98]

- Weaver, Brunas and Brunas wrote that Dracula was known for years as "perhaps the best-known of all vintage horror films".[2]

- film is "rich in historical importance" [2]

- Weaver, Brunas and Brunas described Universal's The Mummy (1932) as more-or-less a remake of Dracula describing it as "a carbon copy right down to individual scenes"[83]

- Lugosi was typecast as a horror film star after Dracula.[99]

- Frye became typecast after Dracula portraying what Weaver, Brunas and Brunas described as "morons, ghouls, and hunchbacks" for the rest of his career.[99] In the press book for The Vampire Bat (1933), Frye stated that "If God is good, I will be able to play comedy in which I was featured on Broadway for eight seasons and in which no producer of motion pictures will give me a chance." and "please, God, may it be before I got screwy playing idiots, halfwits and lunatics on the talking screen!"[99]

References[edit]

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 238.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 21.

- ^ a b c "Dracula (1931)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on July 11, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 23.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 38.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 34.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 40.

- ^ Collins 1930.

- ^ a b c d e Rhodes 2014, p. 43.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 61.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 61-62.

- ^ "Welsh Out of Universal; Laemmle Jr. Takes Helm". Film Daily. May 24, 1929. p. 1.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 89.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 64.

- ^ Merrick 1930.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 86.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Rhodes 2014, p. 90.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 121.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 122.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 123.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 124.

- ^ a b c Rhodes 2014, p. 125.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 126.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 127.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 130.

- ^ "Talking Shadows in the Making". New York Times. August 24, 1930. p. 5. Archived from the original on July 14, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; July 15, 2021 suggested (help) - ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 131.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 132.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 133.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 134.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 135.

- ^ Blair 1930.

- ^ Wilk 1930.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 110.

- ^ "Garrett Fort Adaptation and Dialogue for "Dracula" in Production "Scotland Yard"". Hollywood Filmograph. August 23, 1930. p. 7.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 137.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 46.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 48.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 50.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 51.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 68.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 69.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 145.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 147.

- ^ a b c Skal 2001, p. 121.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 148.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 149.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 150.

- ^ a b c Rhodes 2014, p. 157.

- ^ a b c Rhodes 2014, p. 92.

- ^ Bosco 1944, p. 124.

- ^ Skal 1991, p. 181.

- ^ a b c Rhodes 2014, p. 93.

- ^ "Herman Rosse". Hollywood Filmograph. November 29, 1930. p. 31.

- ^ "Friedman, U's Caster". Variety. Vol. 98, no. 5. February 12, 1930. p. 8 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Hollywood and Los Angeles". Variety. September 24, 1930. p. 69.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 95.

- ^ "Frye for Dracula". The Hollywood Reporter. September 9, 1930. p. 2.

- ^ a b "First Players for Dracula". Variety. Vol. 100, no. 9. September 10, 1930. p. 32. Retrieved July 13, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 96.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 97.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 24.

- ^ Skal 1991, p. 120.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 110-111.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 102.

- ^ Blake 1993, p. 263.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 103.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 106-107.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 107.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 82.

- ^ "Variety's Bulletin Condensed". Variety. August 27, 1930. p. 32.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 113.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 74.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 77.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 78-79.

- ^ "Several Boudoirs". Variety. Vol. 100, no. 11. September 24, 1930. p. 6. Retrieved July 13, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c Rhodes 2014, p. 153.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 159.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 32.

- ^ "Universal's Dracula to Have Romance and Thrills". Exhibitors Herald-World. October 4, 1930. p. 58.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 91.

- ^ Rebello & Allen 1988, p. 217.

- ^ Pulver 2012.

- ^ Arnet 2017.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 245.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 289.

- ^ a b c d e Rhodes 2014, p. 295.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 296.

- ^ a b c Hanke 2014, p. 23.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 290.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 293.

- ^ a b Rhodes 2014, p. 291.

- ^ Rhodes 2014, p. 292.

- ^ Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 366.

- ^ a b c Weaver, Brunas & Brunas 2007, p. 29.

Sources[edit]

- Arnet, Danielle (December 1, 2017). "Vintage 'Dracula' poster set a new world record at auction". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2020.

- Bidgood, Jess (March 11, 2017). "How to Get the Brain to Like Art". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2020.

- Blair, Harry N. (February 24, 1930). "Short Shots from New York Studios". The Film Daily.

- Blake, Michael Francis (1993). Lon Chaney: The Man Behind the Thousand Faces. Vestal Press. ISBN 9781879511095.

- Bosco, Wally (April 1944). "Aces of the Camera: Karl Freund, A.S.C.". American Cinematographer.

- Collins, Charlie (December 1, 1930). "The Stage". Chicago Tribune.

- Hanke, Ken (2014) [1991]. A Critical Guide to Horror Film Series. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-72642-9.

- Merrick, Mollie (June 20, 1930). "Hollywood - In Person". New Orleans Times-Picayune.

- Pulver, Andrew (March 14, 2012). "The 10 Most Expensive Film Posters – in Pictures". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- Rebello, Stephen; Allen, Richard C. (1988). Reel Art: Great Posters from the Golden Age of the Silver Screen. New York: Abbeville Pres. ISBN 0-89659-869-1.

- Rhodes, Gary D. (2014). Tod Browning's Dracula. Tomahawk Press. ISBN 978-0-9566834-5-8.

- Skal, David J. (1991). Hollywood Gothic. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-30805-7.

- Skal, David J. (2001) [1st pub. 1993]. The Monster Show. Faber and Faber Inc. ISBN 0-571-19996-8.

- Weaver, Tom; Brunas, Michael; Brunas, John (2007) [1990]. Universal Horrors (2 ed.). McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2974-5.

- Wilk, Ralph (March 18, 1930). "A Little from 'Lots". Film Daily.