User:Artem.G/sandbox6

Utagawa Yoshifusa[edit]

Utagawa Yoshifusa was a Japanese ukiyo-e master and a pupil of Utagawa Kuniyoshi of the Utagawa school.

His best known work is "Kiyomori’s Visit to Nunobiki Waterfall: The Ghost of Yoshihira Taking Revenge on Nanba" that depicts the ghost of the warrior Akugenta Yoshihira (1141–1160) taking revenge on his murderer Nanba Jirō and is based on the Tale of Heiji. "Akugenta causes lightening to strike his murderer Nanba at the center of the composition, and also shoots flames at his enemy Taira no Kiyomori, who confronts Akugenta on the right. The landscape background is treated in ink monochrome, while Nunobiki waterfall is highlighted in blue against the darkness."[1]

- The Ghost of Yoshihira Taking Revenge on Nanba

commons:Category:Utagawa Yoshifusa

Mochizuki school[edit]

Mochizuki Gyokusen (1692–1755)[edit]

https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q3122702

-

Night Parade of One Hundred Demons

Mochizuki Gyokusen, the Kyoto-based artist of the Cowles handscroll, came from a samurai family and studied with at least two different teachers—one a Tosa-school painter, the other a Kano-affiliated artist. He allegedly created this work as a copy of a sixteenth-century handscroll version of the theme in the collection of the Shinjuan temple of the Daitokuji temple complex in Kyoto.

[3]

Mochizuki Gyokusen (1794-1852)[edit]

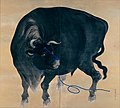

-

Squirrels on Bamboo and Rock, 1812

-

Chrysanthemum and Rock, pair of six-panel screen; ink, color, gofun, gold and silver leaf on paper. 1838.

Mochizuki Gyokusen 玉川 is the third generation of Mochizuki lineage, son of Gyokusen玉仙 (1744-1795) and father of Gyokusen 玉泉 (1834-1913). In his early years, he was known for working on the ninomaru court at Kanazawa Castle as Kishi Ganku’s pupil in 1809. Later he looked up to Matsumura Goshun (1752-1811) of Shijo School and added the bold naturalistic brush style to his own works.

In the present lot, Gyokusen filled up the space with the large, fully-blossomed chrysanthemum. White blooms elaborated with gofun and luxuriant green leaves protrude fearlessly from the naturalistically painted fences and rocks. Gyokusen employed silver leaves to represent the earth slopes (doha). It is not common to have large areas of silver leaf on a gold-leaf ground screen, and traditionally the use of silver leaf is meant for a night scene, usually with a moon in the picture. The silver earth slopes in the present work perhaps demonstrate the moonlight reflection, subtly suggesting a poetic scene of chysanthemum under the moon.

[4]

Mochizuki Gyokusen (1834-1913)[edit]

commons:Category:Mochizuki Gyokusen

Gatherings of literati like the one shown here have long been one of the most popular themes in East Asian art. Mochizuki Gyokusen’s traditional theme and style also show the influence of Nihonga, a Western-style realism prevalent in Japan beginning in the late nineteenth century. It is most apparent in the details of the icy winter world, such as how the flight of a crow from a branch has caused a small shower of snow to fall in its wake. When Gyokusen was barely twenty, he became the head of the Mochizuki family of painters and an official artist of the imperial family in the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. However, he lived most of his life in Kyoto and in 1880 helped establish the Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting. This landscape was produced around that time. Though relatively unknown, Gyokusen was the first teacher of Kawai Gyokudō (1873– 1957), a famous Nihonga artist.

[5]

Kyoto painter Mochizuki Gyokusen IV was well-known for his kacho-e (birds and flowers) and nature subjects. After studying with his father, he also studied the style of the Maruyama-Shijo School, which combined the direct observation and realism of Western artists with traditional Japanese painting techniques. He co-founded the Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting with fellow artist Kono Bairei to encourage younger artists, and was appointed an Imperial Household Artist in 1904, completing many Imperial commissions while also exhibiting internationally. "Gyokusen's Book of Paintings" (Gyokasen shugajo) was published in 1891 in multiple volumes. These charming designs resemble traditional sumi ink paintings, with handsome calligraphic line work, some monochromatic and others accented with soft color. Gyokusen's works are rarely seen outside Japan.

[6]

Guillaume du Vintrais[edit]

ru:Вейнерт, Юрий Николаевич, ru:Харон, Яков Евгеньевич, [2], [3], [4] [5]

Guillaume du Vintrais (c.1553-c.1610) was a fictional 16th-century French poet created by Soviet writers Yuri Veinert and Yakov Kharon while imprisoned in a gulag labor camp in the 1940s.[1]

Fictional biography[edit]

Du Vintrais was born around 1553 in Gascony, France.[2] He was a contemporary of poets such as Pierre de Ronsard and Theodore Agrippa d'Aubigne. As a young man, du Vintrais moved to Paris and became a court poet known for his satirical and politically provocative verses.[3]

In 1572, du Vintrais was imprisoned in the Bastille for his Huguenot beliefs during the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre.[1] After his release, he continued writing poems critical of the monarchy and Catholic church. He went into self-imposed exile in England in the 1580s to avoid further persecution.[2]

Little is known of du Vintrais' later life. He likely died around 1610. The only surviving works attributed to him are 100 French sonnets supposedly discovered in the 19th century.[1]

Poetry[edit]

Du Vintrais' surviving works consist of 100 Petrarcan sonnets written in 16th-century French.[3] The sonnets' themes express the poet's passions for freedom, justice, and romantic love.[1] Literary scholars have noted du Vintrais' talent for using the conventional love sonnet form to subtly voice political and religious dissent.[2]

Many of du Vintrais' satirical sonnets mock the abuses of monarchical power and religious hypocrisy in 16th-century France. References to exile and imprisonment underscore the persecution faced by Huguenots during the French Wars of Religion.[3] Sonnets celebrating poetic inspiration often portray verse as a means of defiance against tyranny. [1]

Nature imagery features prominently across du Vintrais' sonnets, reflecting the growing interest in Neoplatonist philosophy among French Renaissance poets. The style, meter, and diction of his love sonnets suggest the influence of poets such as Pierre de Ronsard, while biblical allusions reflect du Vintrais' Protestant faith.[2]

Du Vintrais was one of the first poets to popularize the sonnet form in French literature. His lyrical mastery of the 14-line structure later influenced 19th-century French sonneteers such as Charles Baudelaire.[3]

History[edit]

Guilleaume du Vintrais never existed. He was invented in the 1940s by Soviet writers Yuri Veinert and Yakov Kharon while they were imprisoned in a gulag labor camp in Siberia.[1]

Veinert and Kharon wrote the 100 fictional French sonnets and crafted an imaginary 16th-century biography for their fictional poet.[2] The two claimed they were merely translating du Vintrais' recently rediscovered work.[3] Literary scholars believe they likely created the poet to subtly express their own passions and critiques without attracting the suspicion of gulag authorities.[1]

Veinert, arrested in 1937, was an amateur poet who began writing verses in exile. Kharon was arrested in the 1930s as part of Stalin's purges of the Soviet intelligentsia. Their friendship blossomed in the gulag through a mutual love of poetry. [2]

The story of du Vintrais' modern "creation" only emerged after Veinert's death in 1951. Veinert and Kharon's fictional sonnets were first privately published in 1947. A more complete version edited by Kharon was released in 1954. The full truth behind du Vintrais was finally made public in the 1980s through journalist Alexei Simonov's friendship with Kharon. [1]

References[edit]

[1] Simonov, Alexei. "Du Vintrais in the Era of Dzhugashvili." Foreign Literature, no. 4 (2013): 237-249.

[2] Vashkevich, Nadezda. "Guillaume du Vintrais, un poète huguenot au goulag stalinien." Renaissance and Reformation/Renaissance et Réforme, vol. 45, no. 2 (2022): 241-254.

[3] Platonov, Rachel S. "The ‘Wicked Songs’ of Guilleaume du Vintrais: A Sixteenth-Century French Poet in the Gulag." The Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 90, no. 3 (2012): 428-449.

hikeshi banten[edit]

- ^ "Utagawa Yoshifusa | Kiyomori's Visit to Nunobiki Waterfall: The Ghost of Yoshihira Taking Revenge on Nanba | Japan | Edo period (1615–1868)". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Summary of Mochizuki School That Was Founded by a Japanese Painter, Mochizuki Gyokusen (望月玉蟾)". Dictionary of Japanese Painters & Calligraphers-SHOGA. 11 September 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "Mochizuki Gyokusen | Copy of Night Parade of One Hundred Demons from the Shinjuan Collection | Japan | Edo period (1615–1868)". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "MOCHIZUKI GYOKUSEN (1794-1852) Chrysanthemum and Rock". christies.com. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "Snow Landscape | Yale University Art Gallery". artgallery.yale.edu. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Mochizuki Gyokusen IV (1834 - 1913) Cherry Blossoms - Fuji Arts Japanese Prints". www.fujiarts.com. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Platonov, Rachel (12 July 2012). "The "Wicked Songs" of Guillaume du Vintrais: a 16th-century French Poet in the Gulag". Slavonic and East European Review. 2012;90(3):428-449.

- ^ Platonov, Rachel S. (2012). "The 'Wicked Songs of Guilleaume du Vintrais: A Sixteenth-Century French Poet in the Gulag". Slavonic and East European Review. 90 (3): 428–449. ISSN 2222-4327.

- ^ "Злые песни Гийома дю Вентре - Воспоминания о ГУЛАГе и их авторы". vgulage.name (in Russian). Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Харон и русский зэк Гийом дю Вентре. Гийом родился в сталинском лагере, а вышел после своих родителей". Новая газета (in Russian). Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Vashkevich, Nadezda (1 December 2022). "Guillaume du Vintrais, un poète huguenot au goulag stalinien". Renaissance and Reformation. 45 (2): 241–254. doi:10.33137/rr.v45i2.39764. Retrieved 27 May 2024.