User:B.Sirota/sandbox/Ver5

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

NewVERS.12 1Mar24. The hypothesis of the bicameral ("two-chambered") mind is about the neurological basis of verbal hallucinations and their cultural importance, especially in ancient history.[1][2][3][4] It asserts that hallucinated voices are caused by the brain's two-sided structure,[5] and that 'voice-hearing' once dominated human psychology, made the first civilizations possible,[6] and was the naturalistic cause of early supernatural concepts and religions.[7][8] The hypothesis is part of a far-reaching psycho-historical theory proposed by research psychologist Julian Jaynes in his 1976 book, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind.[Note 1] Jaynes argues first about consciousness,[a] that it is something "learned and not innate"[9]: 6 [10] and that it began late in the 2nd millennium BCE. He then hypothesizes (drawing on evidence from linguistics, ancient texts and archaeology, as well as behavioral and comparative psychology, so-called "split brain" research, and clinical studies of schizophrenia) that in the preceding millenia humans had a “mentality based on verbal hallucinations"[2]: 452 which he called a bicameral mind because psychologically it had two parts, one dominating the other[3]: 88 but "...neither part was conscious."[1]: 84 [4]: 8

The argument is that ancient humans had sensations and language, and lived mostly habitually just as people do today, but no evidence exists that they had an 'inner self' or 'conscious mind' because they had not learned how to introspect on their own actions and experiences. Instead, the actual ancient records are often about people 'hearing' one or more 'voices of authority' that commanded action, could not be disobeyed, and ruled over daily life.[11] Such "voices of chiefs, rulers or the gods"[12]: 1 were simply 'heard', or were associated with natural phenomena or hand-made 'divine' images.[13] In terms of the hypothesis, this preconscious 'bicamerality' could have evolved if the biological evolution of language produced important language functions in both cerebral hemispheres (not just the left as per mainstream neurolinguistics[14]), so that the right hemisphere could 'speak to' and 'be heard by' the left hemisphere as though it were a separate, superior being.[5]

The hypothesis potentially explains many "otherwise mysterious facts"[8]: 273 of ancient history such as idolatry, polytheism and oracles. Also many modern phenomena with varying degrees of trance or "diminished consciousness",: 324 such as hypnosis and severe schizophrenia, might be explainable as "vestiges" of ancient bicamerality when the brain supposedly worked in a "more primitive"[1]: 432 way than today.[15][16] The hypothesis has influenced modern research into hallucinations in the general population[16] and today voice-hearing is not always judged as mental illness.[17][18][19][20] Groups such as the Hearing Voices Movement seek meaning in the experience[16] which is known to be reported in most, possibly all, cultures, often with a spiritual significance.[1]: 413 [17]: xi Alternative hypotheses about voice-hearing, or auditory verbal hallucinations, have been proposed, but as of 2020, the phenomenon remains poorly understood both neurologically[21] and historically.[17][22]

Jaynes's overall theory, of an evolved bicamerality and of a later, learned consciousness, has been promoted as a "revolutionary idea" and a "new scientific paradigm"[b] that challenges common assumptions about human nature, mental health[23]: 126–131 and religion.[8] One early reviewer called it "ingenious [and] remarkable [... yet] exasperating [in its] incompleteness".[24]: 163 Based on "bold"[25]: 150 interpretations of the known facts, the theory has been described as largely unproveable.[17]: 35 [24]: 164 About Jaynes's approach to consciousness, one early critic rejected it as "absurd",[26] another as "biased" against evolution.[27] Supporters, while acknowledging that "Jaynes’s work is generally dismissed"[28]: 304 or has been mostly "ignored"[12]: 2 by many experts, contend nevertheless (as of 2016) that Jaynes’s theorizing is "ahead of much of the current thinking in consciousness studies"[16][c] and that "critiques of the theory are [mostly] based on misconceptions about what Jaynes actually said".[31]

Context and overview[edit]

Jaynesian psycho-historical theory[edit]

The bicameral hypothesis was one of several components in a "large" psycho-historical[d] theory "covering so much of the terrain of human nature and history".[2]: 447 The theory came to public attention in 1977[e] in The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, a book by Julian Jaynes (1920-1997), a respected lecturer and research psychologist at Princeton University from 1964 to 1995.[32] The book, his one and only, was written for general readers[f] on the results of "his lifelong work"[32]: 47 on the problem of consciousness.[32] The bicameral hypothesis, about the nature and importance of verbal hallucinations in early civilizations, emerged in the context of Jaynes's contention "that a civilization without consciousness is possible".[34]: 47

Background: the problem[edit]

Early in the 1800's psychology was called "the science of consciousness"[35]: 364 and by century's end introspection was not only the main method of study but almost a synonym for consciousness.[35][g] This "traditional view defines consciousness as the direct awareness or immediate experience of the contents and processes of mind [and the] method of observing consciousness, so defined, is introspection".[35]: 365 During the 20th century the traditional view was early on ignored by many in favor of behaviorism[35]: 365 [37]: 13-16 then later on consciousness was defined as awareness[h] and was so studied through brain research. Although the traditional view had been widely abandoned, its problems had not been resolved.[35]: 365 [37]: 13-16 [i] One psychologist in 2006 rephrased the traditional problem as, "Just what is it that makes a brain seemingly "introspectable?""[10]: 174–175

The 'nature' of consciousness[edit]

Jaynes saw the problem of consciousness in traditional terms, affirming that its "denotative definition is, as it was for Descartes, Locke, and Hume, what is introspectable",[38]: 450 one's 'innermost sense of self'[37] and completely distinct from perception.[38]: 447-449 Introspection is something like observation, but without a sensory organ, and whatever mental thing the 'mind's-eye' 'sees' is perhaps the mind itself, or a 'mental state',[j] but it is not the brain's physical reality. Jaynes argued that introspection is an 'inner sense' only metaphorically,[40] and the 'inner space' or 'inner world' of consciousness "must be a metaphor of real space."[40]: 54 Jaynes wrote that "Subjective conscious mind is an analog of what is called the real world",[40]: 55 something like a map that is 'built' first "through metaphorical language"[9]: 1 and then 'operates' (metaphorically) through linguistic or visual metaphors and analogies.[2]: 452 His main claims include: that most of the time people act habitually without consciousness, since it is irrelevant for most behavior but can help to "shortcut behavioral processes and arrive at more adequate decisions";[40]: 55 that "there is no operation in consciousness that did not occur in behavior first";[2]: 449 that consciousness is not a state or process of neurology but a way of using language; it is "learned and not innate",[9]: 6 [10] and is therefore created by culture rather than evolution.[23]: 96 Consciousness has several distinct aspects or features (e.g. mind-space and narratization) which can vary between cultures, and children can learn to do it, at a late stage of language acquisition, only through socialization.[41] Jaynes's view was influential with later social constructivist theorists such as Daniel Dennett.[25]

Consciousness in history[edit]

Jaynes also hypothesized that consciousness had an historical origin about 3,000 years ago, late in the 2nd millenium BCE.[k] On his analysis, there is no clear evidence of interiority or introspection before that era.[42] He argued that consciousness was a cultural "invention"[32]: 36 like agriculture and writing, a "new mentality": 257 that became possible "only after the breakdown"[2]: 453 of an older, non-conscious mentality and cultural system.[11][43] The breakdown of the older mentality was not a specific, one-time event, however, but rather a gradual process stretched over centuries. Certain processes of language change were involved in the historical origin of consciousness,[44]: 216-222 [45][46] and other social processes allowed it to spread across cultures or be learned by children.

Bicamerality[edit]

Jaynes further hypothesized that before the ancient origin of consciousness, human mentality was in fact hallucinatory, with a divided psychology caused by the way language evolved in the two cerebral hemispheres. He came to call it a bicameral (i.e. "two-chambered") mind as "...a rather inexact metaphor to a bicameral legislature of an upper and lower house."[3]: 88 The idea of a "preconscious mentality",: 397 one that was, moreover, based on verbal hallucinations, was so extraordinary that, in anticipation of readers' reactions, Jaynes himself introduced it (with obvious irony) as "preposterous".: 84 Nevertheless, the bicameral hypothesis was intended to explain, as scientifically as possible,[l] a wide range of important facts of the early history of civilizations and religions.[7] The legacy of the bicameral mentality continues and is evident mainly in religious traditions with ancient roots, but also in a variety of persistent forms of "diminished consciousness": 324 which may all have a genetic and neurological basis in the two-hemisphere structure of the human brain.[15]

Since the middle of the 1st millenium BCE, consciousness has flourished and interacted with "the rest of cognition"[2]: 456 to expand human abilities and accelerate cultural change. The transition from bicamerality toward consciousness is an on-going historical process affecting all of human culture.[48]

Implications and significance[edit]

The bicameral hypothesis touches a "staggering" range of subjects,[m] and has many "far-reaching"[50] implications:

- the evolution of language involved both sides of the brain, and the organization of language in the brain is changeable;[5]

- the first verbal hallucinations might have been "a side effect of language comprehension which evolved by natural selection as a method of behavioral control": 134 for early small groups;

- the bicameral system of social control and organization enabled the first agricultural civilizations wherever they arose;[51][6][n]

- bicamerality can explain "our first ideas of gods"[52] as evident in the polytheism, idolatry, and theocracy of ancient societies worldwide;[7][8]: 281–286

- the "weakening": 228 of bicameral 'voices', in part by the invention of writing, can explain the 2nd millennium BCE beliefs in demons and angels which served as "hybrid human-animal": 230 intermediaries to the gods; these supernatural beings were later supplemented by spiritualistic and magical practices, such as divination, incantation of spells, amulets, prayers, and oracles, etc., all aimed at invoking, appeasing or replacing the increasingly absent or unreliable gods;[45][53]

- the inherent instabilities of bicamerality might explain both the slow pace of growth during the early millennia of civilized society, as well as the rapid social breakdown of the 'Bronze age collapse';[54]

- in the modern world, many phenomena may crucially involve "right hemisphere function in a way that is different from ordinary conscious life" and may in some cases involve "a partial periodic right hemisphere dominance".: 324–325 They comprise "a large class of phenomena of diminished consciousness",: 324 or some degree of trance, and only some are hallucinatory, yet all might be "vestiges of the bicameral mind".[15][o] Examples of possible vestigiality are: music and poetry;[55] prophecy, spiritual possession, and glossolalia;[56] hypnosis;[57] schizophrenia;[58] shamanism;[59] and "the 'invisible playmates' of childhood; [...] and hundreds more."[50]

In the final chapter of Jaynes’s book[60] he philosophically interpreted the long cultural transition from bicamerality. Jaynes wonders, "Why should we demand that the universe make itself clear to us? Why do we care?": 433 Noting that "the urgency behind mankind’s yearning for divine certainties": 435 is recorded as the "drama . . . of the central intellectual tendency of world history",: 436 he argues that all modern religious, pseudo-religious and superstitious systems, including "faith in various pseudosciences",: 440 spring from the same psychological discomforts felt when bicameral voices were originally lost.

Modern science can also exhibit "the same quasi-religious gestures" and generate "scientisms [... or] scientific mythologies which fill the very felt void left by the divorce of science and religion in our time.": 441 The historical "secularization of science": 437 expresses the "erosion of the religious view of man [that has been and] is still a part of the breakdown of the bicameral mind.": 439 For Jaynes, religion exists and persists not for metaphysical reasons but because it is rooted in the brain.[61] In 1978, interviewer Richard Rhodes[62] quoted Jaynes, as follows, on the historical relationship between bicamerality and religion:

One of the things I’m trying to protect, […] by identifying its sources, is the function of religion in the world today. The voices are silent. True. But the brain is organized in a religious fashion. Our mentalities have come out of a divine kind of mind.

Consciousness, by contrast, is given a non-metaphysical but also non-evolutionary origin that marks a "radical discontinuity"[61]: 180 between humans and the rest of nature. The "archaic authorization": 320 for civilized action originally came from voice-hearing that controlled behavior, but having broken down, it would to a great degree be replaced by culturally defined selfhood, self-control and moral responsibility. As Jaynes put it:[63]: 79

[V]oices which had to be obeyed were the absolute prerequisite to the conscious stage of mind in which it is the self that is responsible and can debate within itself, can order and direct, [and] the creation of such a self is the product of culture.

Yet such a 'self' is psychologically suggestible and can be displaced, often in trance-like, obedient service to a 'higher power' (e.g. a hypnotist, demagogue, 'demon', or voice): Jaynes proposed a general bicameral paradigm[48]: 323-328 to explain this social process that often "allows a more absolute control over behavior than is possible with consciousness."[57]: 379

Reception and influence[edit]

Jaynes's arguments and conclusions were called "ingenious" and "remarkable", yet also "exasperating" and "incomplete".[p] Some early commentators noted that the arguments for bicamerality are difficult to summarize and explain without "distorting" Jaynes's theory or making it "difficult to take seriously."[q]

Richard Rhodes commented in 1978: "Jaynes's theories…are radical, though well within the traditions of science — he is no Velikovsky or von Daniken bending the facts to sweeten preconception."[62] In 1986, Daniel Dennett argued that Jaynes had sought to maintain "plausibility" acceptable to scientific standards, even though his project was a necessarily "bold" and "speculative exercise" to fill unavoidable gaps in the historical data. It risked the "dangers" of making huge mistakes because it combined an "amalgam of […] thinking about how it had to be, historical sleuthing [for relevant facts], and inspired guesswork".(Dennett's italics)[67]

David Stove wrote in 1989 that Jaynes's "controversial and provocative" theory was "that rarest of things: an absolutely original idea…of most various and far-reaching consequences".[50] Regarding bicamerality and the possibility that humanity experienced an historic change of mentality, Stove commented that "…if such a thing had happened, an astounding number of otherwise mysterious facts would receive an explanation!"[68] and Stove added that "Jaynes has made a definite suggestion, where no one else had a single thing to offer" to explain the existence of religion.[69]

The broad "scope" of Jaynes's argument, evidence and conclusions has been one reason for academic caution and reservation of judgement[r] as well as a possible reason for hostility from scientists.[s] Jaynes's use of ancient texts as evidence was another reason for academic caution or skepticism.[t]

The complexity of Jaynes's "multi-disciplinary" theorizing has been seen as a "reason" that his work has been more ignored than tested or refuted.[12]: 2 One commentator noted that among early critics of Jaynes’s proposals, "everyone could find a topic or conjecture that they disagreed with".[72] If some have indeed ignored Jaynes, the bicameral hypothesis has nevertheless been described as "undoubtedly influential" by Daniel B. Smith in his 2007 book on "rethinking" auditory hallucinations, where he commented that "... perhaps the only thing that [Jaynes's] boosters and critics agree upon is that [bicamerality] can't be proved."[73] Smith argued that Jaynes's theory matters, whether it is correct or not, because "the problem of voice-hearing is in large part indistinguishable from the problem of consciousness, and that the relationship between the two has been fruitful in determining the attributes of each."[73]

Philosophers have been divided in the extreme in their attitude to Jaynes and his ideas. Cavanna et.al. (2007) wrote: "Overall, the attitude of philosophers of mind towards the plausibility of a bicameral mind has been controversial."[74] Philosopher Jan Sleutels in 2006 argued in support of plausibility, but noted that "Jaynes's established repute is now such that the merest association with his views causes suspicion"[75] and commented:[29]

In philosophy [Jaynes] is rarely mentioned and almost never taken seriously. The only notable exception is Daniel Dennett who appreciates Jaynes as a fellow social constructivist with regard to consciousness. Most outspoken in his criticism is Ned Block, who rejects Jaynes's claim as patently absurd.

From an atheist viewpoint, Richard Dawkins in 2006 considered Jaynes's arguments and described his book as "either complete rubbish or a work of consummate genius, nothing in between! Probably the former, but I'm hedging my bets. [...] Whether or not you find his thesis plausible, Jaynes's book is intriguing enough to earn its mention in a book on religion."[76]

Over the years Jaynes's ideas have attracted continuous public attention and occasional academic "reappraisal"[77] or "defense".[78] Researchers have acknowledged that Jaynes was a pioneer in the modern study of consciousness and that his bicameral hypothesis has had "widespread influence",[u] especially regarding the idea of separate roles for each cerebral hemisphere.[79] The hypothesis "inspired much of the modern research into hallucinations in the normal population [since] the early 1980s"[16] and today voice-hearing is not always judged as mental illness.[17][18][19][20] Groups such as the Hearing Voices Movement seek meaning in the experience[16] which is known to be reported in most, possibly all, cultures, often with a religious or spiritual significance.[1]: 413 [17]: xi [80]

The Julian Jaynes Society was founded in 1997, after Jaynes's death, to promote awareness of his work and theories. They maintain a website with a collection of relevant research,[43] and have published collections of essays on related topics. Its founder, Marcel Kuijsten argued in 2016 that Jaynes’s theorizing "continues to be ahead of much of the current thinking in consciousness studies",[16][v] "remains the most supportable and generalizable explanation for the occurrence of auditory hallucinations, and provides voice-hearers with a historical context to better understand their experience."[82] Kuijsten contends that "the vast majority of critiques of the theory are based on misconceptions about what Jaynes actually said".[31]

Section Notes[edit]

- ^ There is no single definition of the term 'consciousness', nor consensus about what phenomena it refers to. In relation to the hypothesis of the bicameral mind, consciousness is, in Jaynes's view, not perception but "what is introspectable."[2]: 450

- ^ Quotations are from the 1990 edition book-cover.[2]

- ^ The Jaynesian approach is social constructivist,[29] and differs from the concepts, goals and methods of cognitive science and neuroscience.[30]

- ^ Jaynes uses the term psycho-historian: 211 (also psycho-archaeology: 177 ) in reference to the history of human mentality in general, not to an individual's psychohistory as the term is used in psychoanalysis.

- ^ The original copyright is from 1976, but the book was not released until mid-January 1977.[32]: 42

- ^ William Woodward, in reviewing the book as a historian of psychology, noted: "The historian of science…must approach [the book] on the level of a popular scientific document which makes use of history" and "the book certainly succeeds in meeting this presentist goal."[33]: 293

- ^ From the MacMillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 1967: "Locke's use of 'consciousness' was widely adopted in British philosophy. In the late nineteenth century the term 'introspection' began to be used. G. F. Stout's definition is typical: "To introspect is to attend to the workings of one's own mind" [... (1899)]."[36]: 191–192

- ^ The equation of consciousness with awareness or perception became popular in the 20th century. The basic definition of the term 'consciousness' as wakefulness came into use during the 19th century.[35]

- ^ "But even if the traditional theory is wrong, something like introspection often takes place."[36]: 193

- ^ The mind's presumed knowledge of itself has been questioned, for example by independent research from as early as 1977 described as the introspection illusion.[39]

- ^ The dating is always an approximation, for example in Kuijsten, "as recently as 3,000 years ago",[9]: 1 or "around 1200 B.C."[23]: 106

- ^ See comments under #Reception and influence: [47][25][8]

- ^ Philosopher David Stove wrote in 1989 that Jaynes "touches, at greater or less length, on a staggering number and variety of subjects, concerning which his theory has implications …"[8]: 271

One example of an explicit list is from James Morriss (1978): "…neurophysiology, anthropology, classical literature, psychopathology, ancient history, general semantics, art, and poetry."[49]: 317 - ^ "The bicameral mind produced a new kind of social control that allowed agricultural civilizations to begin."[3]: 88

- ^ While bicamerality was without consciousness, vestigial phenomena are problematic in that "the trance state of narrowed or absent consciousness is not ... a duplicate of the bicameral mind.": 339

- ^ See Etkin, 1977, p.163: "…it has been a long time since I read anything in the problem of human evolution that was at once so stimulating with original insights and ingenious interpretations yet disappointing, even exasperating, by the incompleteness of its analysis."[24]: 163 Also Marriott, 1980, p.158: "Many questions are raised and remain unanswered… But whether or not the concept of 'bicameral' civilization is convincing, this is a remarkable book. I cannot in this brief review do justice to [Jaynes's] teeming ideas";[64] Woodward, 1979: "…this extraordinary book which defies disciplinary classification…is noteworthy as a primary source which challenges mental evolutionists…[and which] marshalls literary and archaeological evidence for a question central to language, religion, and science — the origin of consciousness."[33]: 292

- ^ See Marriott, 1980, p.158: "I cannot in this brief review do justice to [Jaynes's] teeming ideas, to the range of his learning in half a dozen disciplines. His arguments are inevitably simplified and distorted here."[64] Also Morriss, 1978, p.316: "Unaccompanied by Jaynes's arguments and evidence, a brief explanation of his thesis is inadequate";[65] and Etkin, 1977: "Stated thus briefly without illustrations [Jaynes's] argument is difficult to take seriously."[66]

- ^ Woodward, 1979, p.293: "One is tempted to reserve judgement on such a daring thesis as this, realizing that it demands an impossibly broad range of knowledge to endorse or refute."[70]

- ^ Jones, 1979, p.23: "…all probably agree that, the more inclusive the hypothesis, the looser the fit [with evidence] is likely to be, [and] we ought to be willing to tolerate a certain looseness of fit in hypotheses of very great scope. …neurologists, archaeologists, linguists and psychologists might make…differential assessments of the [evidence] that reflect a differential tolerance for looseness of fit on the part of the scientists concerned. Nevertheless, and taking Mr. Jaynes' argument as a whole, I also predict that the reaction of most scientists would be skeptical if not hostile."[71]

- ^ Etkin, p. 164: "To one trained to look for objective evidence such [literary analysis] carries no strong conviction, especially since even superficial acquaintance with the sources suggests much that does not fit into the author's pattern… Few students of behavior venture this path."[66]

- ^ Cavanna, et al. (2007): "Jaynes' thought-provoking and pioneering work in the field of consciousness studies gave rise to a longlasting debate[;]"[77]: 11 and "Jaynes' composite picture of the bicameral mind has had widespread influence and undoubtedly shaped to a considerable extent subsequent reflections on the biological and cultural underpinnings of human consciousness."[77]: 13

- ^ The Jaynesian approach stands apart from that of 'consciousness studies' which focuses on phenomena and concepts that "in Jaynes's view...are inappropriate targets for the word consciousness."[81]

Argument and evidence[edit]

The bicameral hypothesis, that there once was a mentality different from consciousness and it was all about 'gods' who were hallucinations, is an inference from "multiple independent sources of evidence"[83] which can be interpreted in many ways.

The possibility of a preconscious mentality[edit]

The Jaynesian idea, that humans could, and at one time did, live without consciousness (i.e. introspection, or "interiority"[84]), is not easy to understand or explain.[a]

Introspection, which for Jaynes is the sole basis of any "conception of what consciousness is,": 18 identifies "a succession of different conditions which I have been taught to call thoughts, images, memories, interior dialogues, regrets, wishes, resolves, all interweaving with the constantly changing pageant of exterior sensations of which I am selectively aware.": 23 Such are the 'contents' of recalling, reminiscing or reflecting on experience and behavior, or imagining past and future possibilities.[b] All these, however, are "a much smaller part of our mental life than we are conscious of, because we cannot be conscious of what we are not conscious of[...]!"[34]: 23 Behaviorism and experimental psychology in the 20th century have shown that much of human activity, like that of other animals, involves physiological processes that are mostly automatic and habitual. One can acquire scientific knowledge that such neural and cognitive processes exist and 'be conscious' of them when 'reflecting' on them, even though they cannot be experienced.[34][c]

Jaynes criticized "superficial views of consciousness that are embedded both in popular belief and in language"[2]: 447 which treat it as 'all of mentality' or as "that vaguest of terms, experience";: 8 or they fail to distinguish "between what is introspectable and all the hosts of other neural abilities we have come to call cognition"[2]: 447 including processes of awareness (which he called "reactivity": 22 ), attention, perception, and automatic learning, problem-solving or decision-making which all happen either without any experience of the process, or before any consciousness of the result.[9]: 8–9 [88]: 20–30 Not only is consciousness far less of mentality than is commonly supposed, it is neither a constant nor necessary condition for most behavior;[d] nevertheless our "consciousness of consciousness" seems to provide knowledge of what is called one's 'inner self' and one's own 'conscious mind'.[34]

It was the idea of interiority[37]: 9 [e] — of the mind as a 'space' filled with 'mental entities' or 'mental events' — that Jaynes defined as the "primary feature" among several[f] that comprise the "basic connotative definition of consciousness."[g] When people speak about private thoughts, or 'mental life', it is simply a part of what it means to be conscious to speak as if there is a "mind-space inside our own heads as well as the heads of others".[40]: 60 The 'mental activities' that supposedly occur 'in the mind', like all human physical activities, certainly involve the brain, but nobody has direct experience of their brain at work, and introspection can never reveal how the brain works (i.e. nerve impulses, synapses, etc.). Phrases like the 'inner world' or 'mind's eye' of introspection refer to the mind and its 'contents', not the brain; however, the mind can only be described or talked about with words that normally describe the 'external' physical world,[h] as Jaynes puts it:[4]: 6

Every word we use to refer to mental events is a metaphor or analog of something in the behavioral world.

Jaynes explains further that it is generally through the use of metaphors that people feel that they understand anything at all,[i] and he develops an original theory of metaphor to explain how the assumed mind-space and other features of consciousness operate. By assuming and speaking of the existence of a 'mind', 'soul', 'inner world' or 'inner self', people learn to act and to explain everyone's behavior as if caused or controlled by something 'on the inside'.[44]: 217 [j]

Furthermore, if consciousness is based on linguistic metaphors and analogs, then it can only be a human ability, and can emerge only at a certain level of linguistic and social complexity.[41] Therefore, says Jaynes, consciousness cannot be innate, and is a product of language and culture, not biological evolution.[k] And if it is not a necessary part of human psychology, then a society could have once existed with people "who spoke, judged, reasoned, solved problems" and more, without ever having learned to be conscious at all.[34]: 46-47

Four clues from history and psychology[edit]

The oldest 'mind words'[edit]

Jaynes notes that if the earliest remnants of the invention of writing can be deciphered at all, correct translation requires much scholarly guesswork based on facts from other bodies of knowledge. He argues that the standard approach of translators is to apply modern psychological ideas when trying to understand ancient mysterious facts, a method which naively assumes that human psychology thousands of years ago was fundamentally the same as it is today. Jaynes writes:[92]: 177

When the terms are concrete, as they usually are, for most of the cuneiform literature is receipts or inventories or offerings to the gods, there is little doubt of the correctness of translation. But as the terms tend to the abstract, and particularly when a psychological interpretation is possible, then we find well-meaning translators imposing modern categories to make their translations comprehensible [... and] to make ancient men seem like us[.]

The presence of consciousness in the past can only be inferred,[10]: 185–186 and only when certain words are in a context referring to the existence or acts of a person’s 'inner' being. Contrary to ordinary assumptions, Jaynes argues that no words for 'the mind' as we understand it today are found at all in the oldest texts, especially those that are well-understood, such as Greek[46] and Hebrew.[93]: 296 [l]

Example: The Iliad[edit]

The Iliad, an epic poem based on oral traditions from the 12th century BCE, was written down about 400 years later, and may be "the earliest writing […] in a language that [modern readers] can really comprehend".[63]: 82 Jaynes analyzes this well-studied source of Greek mythology, and makes the case that the oldest parts, in Homeric Greek, tell nothing of an 'inner life', which allows the possibility that at one time it did not exist. In Jaynes's words:[63]: 75

Iliadic man did not have subjectivity as do we; he had no awareness of his awareness of the world, no internal mind-space to introspect upon.

Bruno Snell made a similar point: "...there is in Homer no genuine reflexion, no dialogue of the soul with itself."[94][m] This contrasts with late classical Greek literature of the middle 1st millennium BCE.[46][95] Jaynes emphasizes that the Greek words with mental meanings in later centuries are originally, in the Iliad, always concrete, referring to limbs, organs or bodily actions; Jaynes analyzes key terms, including psyche, noos, thumos, phren, mermerizein, (also soma)… [46]: 69–71 and discusses as well how they eventually transformed into mental words.[46]: 257-272 [n]

The 'gods' preceded 'mind'[edit]

"... THE DUEL OF HECTOR AND AJAX... Loud rang the bronze, but the shield brake not. Then Ajax took a stone... But Apollo raised [Hector] up... Then did both draw their swords; but ere they could join in close battle came the heralds, and held their sceptres between them, and Idasus, the herald of Troy, spake: — Fight no more, my sons; Zeus loves you both, and ye are both mighty warriors."

Without the use of mental vocabulary, the Iliad explicitly depicts its human heroes as being stirred into action by ‘gods’, and they explain their own behavior as caused by gods who themselves take part in the action. The humans never "sit down and think out what to do".: 72 Jaynes considers that these interactions between 'gods' and ordinary humans are similar to modern hallucinations, which are reported as 'voices', most often by people diagnosed with psychosis.[96]: 85-94

This "suggests": 75 an entirely new psychological interpretation of the 'mythological' content of the Iliad and its epic poetry form: that the Homeric gods were not simply imaginative poetic devices, and Greek society before the 5th century BCE took the gods seriously;[o] furthermore, that in the late Bronze Age and for centuries into the early Iron Age, those who recited or heard the heroic tales accepted the reality of the gods because people commonly experienced god-voices in their own hallucinatory way. The Iliad becomes for Jaynes "a psychological document of immense importance",[63]: 69 providing one ancient clue to the hallucinatory mentality that he calls the "bicameral mind".[p]

Modern hallucinated voices[edit]

Based partly on his own clinical work and research, Jaynes argues that by the mid-20th century, the little that was scientifically known about verbal hallucinations had been learned mostly during the medical treatment of psychosis and schizophrenia.[1]: 87-88 [58] He recognizes that 'voices' have been generally feared as a sign of insanity requiring treatment, although in some cases they "may be helpful to the healing process";: 88 and they may have been the source of inspiration to "those who have in the past claimed such special selection": 86 as to hear voices of prophecy. Hallucinated voices may be "heard by completely normal people to varying degrees […] often in times of stress [or] on a more continuing basis."[96]: 86 Voices occur in all age-groups, come from any location and from every direction, and even "profoundly deaf schizophrenics insisted they had heard some kind of communication.": 91 The experience is varied and complex:[96]: 88-89

The voices in schizophrenia take any and every relationship to the individual. They converse, threaten, curse, criticize, consult, often in short sentences. They admonish, console, mock, command, or sometimes simply announce everything that's happening. They yell, whine, sneer, and vary from the slightest whisper to a thunderous shout. Often the voices take on some special peculiarity, such as speaking very slowly, scanning, rhyming, or in rhythms, or even in foreign languages. There may be one particular voice, more often a few voices, and occasionally many. [They] are recognized as gods, angels, devils, enemies, or a particular person or relative. Or occasionally they are ascribed to some kind of apparatus reminiscent of the statuary which we will see was important in this regard in bicameral kingdoms.

Medical cases differ in degrees of severity. But why are voices at all "believed, why obeyed"? Because "the voices a patient hears are more real than the doctor's voice.": 95 It is normal for healthy, conscious humans to be highly attentive and compliant to 'real' voices of those in recognized authority, especially when the voices are located nearby, and sound is a modality that cannot be shut out. Hallucinated voices cannot be silenced by force of will and if they can be resisted it is only with struggle, even if they command harmful or self-destructive behavior (as so-called command hallucinations often do). In less severe cases, some patients "learn to be objective toward them and to attenuate their authority […though at first there is always] unquestioning submission […] to the commands of the voices."[96]: 98

Language and the cerebral hemispheres[edit]

If the ‘hearing of voices’ has any physiological basis at all, then it has something to do with the way language is organized in the brain.[5]: 100 Jaynes acknowledges and reviews the known facts of his day showing that language is essentially a function of one cerebral hemisphere, most commonly the left.[q] He asks why this should be so, and why "those areas on the right hemisphere corresponding to the speech areas of the left" should seem to have “no easily observable major function”, yet can, under certain conditions, take over partial or full language functions. Jaynes speculates about the evolution of "their important function, since it must have been such to preclude [right hemisphere] development as an auxiliary speech area[.]"(original italics)[5]: 102-103

Research by Wilder Penfield from the 1950's showed that 'voices' could be 'heard' by patients when the right cerebral cortex was electrically stimulated.[5]: 106-112

Ground-breaking 1960s studies of the so-called "split brain"[r] showed not only that the right hemisphere can understand language, but the two hemispheres can behave with a great deal of apparent independence, while the left hemisphere alone seems to be associated with a person's self-identity.: 112–117

Jaynes incorporates such evidence to support the “tentative”: 103 possibility that verbal hallucinations generally come from the language areas of the right cerebral hemisphere and, if so, would sound to the left hemisphere as if spoken by another being.[5]

Aspects of Jaynes's hypothesis[edit]

Bicameral mind and bicameral society[edit]

The existence and character of the ancient system are "demonstrated in the literature and artifacts of antiquity."[38]: 456 The bicameral mind is describable, however, only by comparison, partly to modern consciousness, and partly to modern hallucinations, about which too little is known.[s] Other than what people say of their experience, there is no explicit, objective method to verify the existence or character of hallucinations that seem externally real, just as the same is true of an 'inner life' of consciousness.

A divine mentality[edit]

The preposterous hypothesis we have come to is that at one time human nature was split in two, an executive part called a god, and a follower part called a man. Neither part was conscious. This is almost incomprehensible to us. And since we are conscious, [we] wish to understand[.][96]: 84

In distinction to our own subjective conscious minds, we can call the mentality of the Myceneans [and their era] a bicameral mind. Volition, planning, initiative is organized with no consciousness whatever and then 'told' to the individual in his familiar language, sometimes with the visual aura of a familiar friend or authority figure or 'god', or sometimes as a voice alone. The individual obeyed these hallucinated voices because he could not 'see' what to do by himself.[63]: 75

For this [hypothesis], the evidence is overwhelming. Wherever we look in antiquity, there is some kind of evidence that supports it [...] Apart from this theory, why are there gods? Why religions? Why does all ancient literature seem to be about gods and usually heard from gods?[38]: 452

The hallucinatory roots of civilization[edit]

The bicameral mind is ... that form of social control which allowed mankind to move from small hunter-gatherer groups to large agricultural communities. [It] evolved as a final stage of the evolution of language [in which] lies the origin of civilization.[6]: 126

Human group-life and language evolved together.[6] Pre-historic groups were small, their patterns of behavior were simple, and they "moved through their lives on the basis of habit — just as we do" today.[3]: 88 While language was simple and vocabulary was still too concrete for consciousness, the ancients "knew what followed what and where they were, and had behavioral expectancies and sensory recognitions just as all mammals do".[38]: 456 While routine behaviors would have been manageable by the vocal commands of a living parent or leader, repeatedly given as needed, social cohesion would be enhanced by the ability to recall the leader's commands.

The first hallucinated 'voices' may have been echoes of real vocal signals that evolved along with language comprehension to allow long-term behavioral control.[6]: 134–135 Larger groups, however, required more than the simple hallucinated memory of a leader's commands: the 'voices' "could with time improvise and 'say' things that the king himself had never said", just as "the 'voices' heard by contemporary schizophrenics 'think' as much and often more than they do[.]"[6]: 141

Before about 9000 BCE "voices would have played a minor role"[99] but provided the "system of social control"[83] that enabled the more complex life of settlements and agriculture in the first civilizations. This was the case in the oldest civilizations until about 1000 BCE, after which voices became a "hindrance".[99] Such was the case also in different parts of the world and in younger civilizations where the "advance to consciousness occurred quite late" (as perhaps occurred among the Incas after "their conquest by Pizarro").[49]: fn.28

Social control by 'voices'[edit]

Although modern, and presumably ancient, hallucinated voices occur within the individual's brain, they sound as 'real' and external as any human voice, and often more authoritative.[80] Jaynes claimed that:[58]: 409–410

... auditory hallucinations in general are not even slightly under the control of the individual [patient], but they are extremely susceptible to even the most innocuous suggestion from the total social circumstances of which the individual is a part. In other words, [...] hallucinations are dependent on the teachings and expectations of childhood — as we have postulated was true in bicameral times.

Hallucinations are thus dependent on cultural context as well as neurology.[17][80] This applies to modern voice-hearers (who live in a world of consciousness) and especially to schizophrenic patients who struggle with "hallucinations that are unacceptable and denied as unreal" by others.: 432 Bicameral people, however, lacked consciousness and could neither 'see for themselves' nor, for lack of an 'inner self', could they 'tell themselves' what to do; and, for lack of a culture of consciousness, they could not have deduced, imagined or even made sense of the modern idea that such voices 'came from their own heads'.

The archaeological record of the most well-understood early civilized societies and kingdoms, when they were stable, presents a rigid hierarchic structure, with divine beings at the top; the bicameral interpretation is that everybody relied on voices of authority, whether they were from a real person or a hallucinated divinity, that told the individual what to do. Civilized life, which Jaynes described as "the art of living in towns of such size that everyone does not know everyone else",[7]: 149 required bicameral authoritarianism, but he argued it was not oppressive:[44]: 205

...the bicameral mind was the social control, not fear or repression or even law. There were no private ambitions, no private grudges, no private frustrations, no private anything, since bicameral men had no internal 'space' in which to be private, and no analog 'I' to be private with. All initiative was in the voices of gods. And the gods needed to be assisted by their divinely dictated laws only in the late federations of states in the second millennium B.C.

Within each bicameral state, therefore, the people were probably more peaceful and friendly than in any civilization since.

Experiencing bicameral voices[edit]

In the modern world, occasions of learned conscious thinking are normal events in the context of otherwise habitual life;[t] when hallucinations occur, they are often "triggered by stressful, confusing, or "fight or flight" situations."[100] In bicameral times, when habitual, repetitive activities presumably dominated life, the threshold for psychological stress was probably much lower than today. Any decision-making situation, where "a change in behavior was necessary because of some novelty",[96]: 93 or where a problem was somewhat too complicated for normal habits, "was probably sufficient"[4] to trigger a voice.

Bicameral decision-making, an entirely unconscious process, was based on a lifetime of "admonitory experiences", i.e. being told by others what to do.: 93–94 A bicameral voice did not reason or 'think out loud' (as conscious people do) to solve a problem or make a decision. The 'voice' simply conveyed the result of non-concious, automatic processes of the nervous system: 37, 40, 42 in the form of a message or command. Today, the outcomes of similar processes are sometimes evident in the content of a person's consciousness, while consciousness is falsely deemed to be the source of the decision. In bicamerality, the habitual conditioning by accumulated experiences and the general social order could generate an admonitory 'voice'.[42]: 36–44

When the ancient individual heard a voice speaking a command, the command was authoritative and could not be disobeyed because it expressed the brain's unconscious volition.[42]: 98–99 However, at no time could a 'voice' be described or dismissed as 'one's own': for the bicameral human with no mind-space or conscious self-identity, there was no ability to judge the wisdom of the received messages, and disobedience would be literally unthinkable. Jaynes wrote:[96]: 98

. . . if one belonged to a bicameral culture, where the voices were recognized as at the utmost top of the hierarchy, taught you as gods, kings, majesties that owned you, head, heart, and foot, the omniscient, omnipotent voices that could not be categorized as beneath you, how obedient to them the bicameral man!

A visual component[edit]

Besides the stress of decision-making, certain sounds, such as wind and waves, might have had hallucinogenic effects in bicameral times, and so too could many visual stimuli, such as awe-inspiring vistas, clouds, sea mists, strange lighting and shadows, drawings, carved images, and ritual objects including stone idols.[13] Visual hallucinations are less commonly reported than auditory, but when they occur with voices, usually "they are merely shining light or cloudy fog",: 91–93 and they often have "flitting and bird-like movements.": 193

The Jaynesian "double brain" model of hallucinations[edit]

In the 1990 edition of his book, Jaynes specified that his psycho-historical theory consists of four "separable" hypotheses.[38]: 456 They are: the nature of consciousness; the dating of the 'dawn of consciousness'; the existence and character of the preconscious bicameral mind; and the proposed neurological model for hallucinations. Of the four hypotheses, his "double brain" neurological model for 'voices' is the one that is theoretically testable, but Jaynes knew "it would be decades before...his ideas could be tested."[101]

The neurological model underlying the bicameral mind was inspired by mid-20th-century discoveries about the cerebral hemispheres. The important and surprising facts included that both sides could comprehend language while only the left controlled speech, and that 'voices' could be 'heard' by electrical stimulation of the right hemisphere's cerebral cortex.[5]: 106-112 So-called "split brain" studies, especially, were not only demonstrating the conditional independence of the hemispheres,: 112–117 but were also generating much popular and scientific discussion about altered and complementary "modes of consciousness" (e.g. propositional/appositional, verbal/visuospatial, analytic/holistic) that were possibly related to the duality of the cerebral hemispheres.[u]

Jaynes assumed that modern language functions are normally localized and lateralized in the left hemisphere, but he hypothesized that archaic processes of language communication between the hemispheres could provide a neurological explanation to support his bicameral hypothesis.[5]

Bicameral and non-bicameral hallucinations[edit]

Jaynes's neurological model is meant to explain ancient hallucinations primarily, on the assumption that they are similar but not identical to modern hallucinations since conscious people who "relapse" into hallucinations are not bicameral.[38]: 455 About schizophrenia, Jaynes wrote:[58]: 431-432

... whether one illness or many, is in its florid stage practically defined by certain characteristics which we have stated earlier were the salient characteristics of the bicameral mind. [...] But there are great differences as well. If there is any truth to this hypothesis, the relapse is only partial. The learnings that make up a subjective consciousness are powerful and never totally suppressed. And thus the terror and the fury, the agony and the despair. [...T]he florid schizophrenic is in an opposite world to that of the god-owned laborers of Marduk or of the idols of Ur.

Jaynes allowed that his neurological model "could be mistaken (at least in the simplified version I have presented) and the other [hypotheses] true."[38]: 456 The model attributes voices, especially in the ancient bicameral mind, to the "amalgams of admonitory experience" — such as remembered commands from parents — that were "stored" in the RH (right hemisphere).: 74, 106, 428 The RH would be activated by "decision stress" to send a communication to the LH. Jaynes argues that a linguistic "code" (i.e. a verbal command) would be "the most efficient method of getting complicated cortical processing from one side of the brain to the other."[5]: 105-106 Excitation from the RH is the critical factor, and the most likely short route for a RH message to be transferred to the LH (which holds Wernicke's area) is through the anterior commissure because that is a direct physical connection between the RH and LH temporal lobes.: 103–104 [v]

Jaynes proposed two variants of his neurological model. The "stronger" variation, supposedly easier to test, is that 'voices' are generated entirely in the RH to be 'heard' in Wernicke's (LH) area. The weaker (and vaguer) model would still have excitation originate in the RH, but the "articulatory qualities of the hallucination" would somehow involve the normal LH location for speech-production, i.e. Broca's area.: 105–106

Evolutionary speculations[edit]

Language: Jaynes outlined his own theory of language evolution to account for language in both hemispheres and to focus on the social functions of vocabulary. The earliest humans, with little or no language, lived in very small groups which must have been organized to manage their strict social hierarchies, like those of other primates, using mostly "postural or visual signals" in accordance with the principles governing primate sociality.[42]: 126–131 Vocabulary may have grown through a series of stages, from vocal signals, to modifiers, then to nouns, and then to the invention of names perhaps around 10,000 BCE. Names enabled the management of individuals within larger, settled populations. The evolution of names was a necessary step towards the hallucinatory function, which was a side-effect of language comprehension.: 134

For preconscious humans — they could not tell themselves what to do — the ability to 'hear' the leader when the leader was absent, and to identify the 'voice' with the leader's name, would have provided evolutionary advantages.: 126–127 Bicameral voice-hearing would have enhanced the cohesion of a small group and reinforced the mechanisms of social control over larger populations, enabling individuals to persist at the long-term tasks which were essential for the transition from prehistoric hunter-gatherer societies to agricultural economies.

Brain plasticity: Jaynes also advocated for a concept of plasticity in the child's brain, based on evidence that under certain conditions "the normally preferred modes of neural organization": 124 are bypassed, and he speculated that the modern functional organization of the brain was achieved by selective pressure against bicamerality: "after a thousand years of psychological reorganization in which [...] bicamerality was discouraged when it appeared in early [childhood] development, [the right hemisphere language] areas function in a different way."[5]: 125

Section Notes[edit]

- ^ Richard Rhodes commented on this difficulty: "Man without language is easy: a superior primate. Man without consciousness is hard to compass."[85]

Owen Barfield also: "The consciousness of 'myself' and the distinction between 'my–self' and all other selves, the antithesis between 'myself', the observer, and the external world, the observed, is such an obvious and early fact of experience to every one of us, such a fundamental starting point of our life as conscious beings, that it really requires a sort of training of the imagination to be able to conceive of any different kind of consciousness. Yet we can see from the history of our words that this form of experience, far from being eternal, is quite a recent achievement of the human spirit [. . .] that seems to have first dawned faintly on Europe at about the time of the Reformation".[86] - ^ In a 1986 lecture, Jaynes asked: "But what then is consciousness, since I regard it as an irreducible fact that my introspections, retrospections, and imaginations do indeed exist?"[4]: 6

- ^ Jaynes extensively discusses what consciousness "is not", and why it is distinct from the cognitive processes that occur without it.[34] Similar statements about 'non-conscious' processes include: Gigerenzer (2007) "...much of our mental life is unconscious, based on processes alien to logic: gut feelings, or intuitions[, ...] on rules of thumb, and on evolved capacities";[87]: 3–4 and Kahneman (2011) "You believe you know what goes on in your mind, [but m]ost impressions and thoughts arise in your conscious experience without your knowing how they got there."[88]: 4 Oakley & Halligan (2017) and Rowe (2016) explicitly distinguish between consciousness and "executive functions" of the brain.[89][41]

- ^ Compare Kahneman, 2011: "When we think of ourselves, we identify with System 2, the conscious, reasoning self that has beliefs, makes choices, and decides what to think about and what to do [and] believes itself to be where the action is, [... whereas ...] System 1 runs automatically and System 2 is normally in a comfortable low-effort mode, in which only a fraction of its capacity is engaged."[88]: 21–24

- ^ In light of the definitional ambiguities around the term "consciousness", one of Jaynes's students, Brian McVeigh, has suggested that the term "interiority" better signified Jaynes's meaning.[90]: 42

- ^ Jaynes's 1976 analysis elaborates the following specific features of consciousness: spatialization, narratization, excerption, the analog ‘I’, the metaphor ‘me’, and conciliation. In the Afterword of the 1990 edition, he added concentration and suppression. All are causally dependent on linguistic metaphors or analogies of behavioral processes.[40] The list is not meant to be exhaustive or universal.[2]: 450-451

- ^ In the Afterword of his 1990 edition Jaynes wrote: "The basic connotative definition of consciousness is thus an analog 'I' narratizing in a functional mind-space. The denotative definition is [...] what is introspectable."[38]: 450

- ^ In an earlier work on ancient Greek language and philosophy, Bruno Snell recognized the significance of physical descriptions of the 'mind', writing: "We cannot speak about the mind or the intellect at all without falling back on metaphor."[91]

- ^ In his book, Jaynes asserts: "Understanding a thing is to arrive at a metaphor for that thing by substituting something more familiar to us. And the feeling of familiarity is the feeling of understanding."[40]: 52

- ^ Later research refers to this process as the development of theory of mind as part of the development of consciousness in children.[41]

- ^ Consciousness is "a cultural introduction, learned on the basis of language and taught to others, rather than any biological necessity."[44]: 220

- ^ Compare the transitions from 1st millennium usage of Hebrew nephesh and ruah with Greek psyche and pneuma, Latin anima and English spirit and soul in the Bible.

- ^ Jaynes mentions "Snell's parallel work on Homeric language" in a footnote on page 71.

- ^ Jaynes finds a "key to understanding" the eventual development of Greek consciousness in the history of the listed "mindlike terms in the Iliad".: 257 He refers to those terms as the "preconscious hypostases", meaning those things which, being "caused to stand under something", become "the assumed causes of action when other causes are no longer apparent."[46]: 259

- ^ Bruno Snell, in 1948, asserted the seriousness of Greek belief: "...[the Greeks] looked upon their gods as so natural and self-evident that they could not even conceive of other nations acknowledging a different faith or other gods. [...] The existence and the power of the gods are no less certain than the reality of laughter and tears..." And the earliest evidence of Greek 'atheism' appears only near the end of the 5th century BCE.[97]

- ^ This is the point in Jaynes’s book where the term is first mentioned.[63]: 75

- ^ "Language is considered to be one of the most lateralized human brain functions. Left hemisphere dominance for language has been consistently confirmed in clinical and experimental settings and constitutes one of the main axioms of neurology and neuroscience. However, [recent] functional neuroimaging studies are finding that the right hemisphere also plays a role in diverse language functions."[14]

- ^ Jaynes pointedly emphasizes that the term is misleading: "The so-called split-brain operation (which it is not — the deeper parts of the brain are still connected)...": 113

- ^ As recently as 2015, "...systematic empirical research on the phenomenology of auditory hallucinations remains scarce."[98]

- ^ The first chapters of Jaynes's book explain that consciousness is not a constant or continuous thing, though it seems so to itself.

- ^ See, for example, Robert Ornstein's compilation from 1973, "The Nature of Human Consciousness: a book of readings", with articles by Michael Gazzaniga, Joseph Bogen and others.[102]

- ^ In a footnote Jaynes explicitly acknowledged that the anterior commissure had other known functions besides the bicameral.: 105

Bicameral interpretations of ancient facts[edit]

The pattern of evidence[edit]

The bicameral hypothesis permits an interpretation of archeological and historical facts that accounts for the general pattern, says Jaynes, of "social organization [...] wherever and whenever civilization first began"[7]: 149 and specifically "the entire pattern of the evidence [of] the dead as gods in different regions of the world".[7]: 165 The hypothesis connects seemingly disconnected facts[a] and explains apparent mysteries.[8]: 273 For example, on the subject of the "Corpse/Personator Ceremony" in early China, Michael Carr wrote:[104]

There are already various non-bicameral explanations for […] all […] Chinese death beliefs and customs. However, without the bicameral hypothesis, at least one explanation has to be proposed for each of them. Proposing many different reasons for corresponding traditions across cultures ignores what Jaynes calls "the entire pattern of the evidence."

Early bicamerality[edit]

Such preserved skulls of the dead, like others found at Ancient Jericho, may have inspired 'voices'.[11]: 151

There are "several outstanding archeological features of ancient civilizations which can only be understood", says Jaynes,[11]: 150 according to the bicameral hypothesis. They include the burial of "the important dead as if they still lived";: 161 the ubiquitous use of idols, statuary and figurines; the monumental architecture, especially of 'god-houses' (i.e. temples) "in which no one lived, no grain was stored, and no animals were housed".[51]: 64 Jaynes presents evidence from ancient Sumeria, Ancient Egypt, Ancient Jericho, the Hittites, the Olmec, Maya, and the Inca.[51]: 62 [b]

The living dead. The hallucinated 'voice' of a group leader would still be 'heard' after the leader's death, and so the leader could seem, at least for a time, as still giving commands.[6]: 138-143 [105] Such an experience can explain the origin, as early as 9000 BCE,[51]: 55 of certain ceremonial treatments of the dead as still living.[51]: 66–67 One was burial beneath the home (as at Tel Jericho) or at the dwelling entrance (as at the "Pre-Pottery Neolithic B site of Tel Halula").[51]: 62 Another was the practice by Paleolithic skull cults of severing the head from a corpse and preserving the skull (as at Göbekli Tepe).[106] In many places there was a "double burial of the same corpse", perhaps because the 'voices' had stopped being heard.: 141 : 151 Elaborate mummification rituals, practised for thousands of years and in widely separated parts of the world, were aimed at preserving a physical body, perhaps to satisfy the 'afterlife' demands of a still-heard voice. In later millennia, texts refer to the dead persisting as "ghosts" if not "as gods".[51]: 66–67

The Natufian example

The "best defined and most fully studied Mesolithic culture [is] the Natufian[,]" located at Eynan in present-day Israel.: 138 By 9000 BCE they had a population of 200-300 persons living a settled life with primitive agriculture. It was a group too large to be manageable merely by signals and simple commands. They may have been a bicameral community. Natufians practiced ceremonial burials. The dead Natufian king appears to have been propped up in his elaborate tomb-dwelling — "the first such ever found (so far)" — as if he were still alive, as if...

...in the hallucinations of his people still giving forth his commands, [... which] was a paradigm of what was to happen in the next eight millennia. The king dead is a living god. The king’s tomb is the god’s house, the beginning of the elaborate god-house or temples[.][6]: 143

Statuary. A prominent feature of nearly all early settlements was a place of some kind for cultic statuary. It was not uncommon for a shrine to be located in a personal dwelling (e.g. 7th-6th millennium Çatal Hüyük). Some of the most common and oldest artifacts are strangely formed figurines, statues and cultic images, and thousands of them are small enough to hold in the hand. Many such figurines may have served as hallucinogenic devices: 152, 243 that stimulated the 'hearing' of bicameral voices.[6][7]

Monumental god-houses. The burial mounds found around the world were pre-cursors, in many places, of "tremendous architectural investment"[107] in the construction of complex tombs such as the ancient pyramid. Many such tombs for the 'living dead' served as the center of communal life where the "god-king's" presence was long-lasting, if not eternal. The first temples were possibly based on the function of a king's tomb as a "god-house". Alternatively, many large settlements and cities, for example 7th millennium Tel Jericho, or the later ziggurats of Ur,: 151–153 had a centrally located temple that housed a 'speaking' statue-god or life-sized effigy who could rule for multiple generations and in many places at once.: 144 Such was probably the case in Mesopotamia, where the cultic statues were maintained for generations by a dead king's successors acting as a servant priest of the statue-god.: 143 [7]: 150-164

Theocratic kingdoms[edit]

Of the great cultures of pre-classical antiquity, ancient Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt are the two most studied and best understood. Their extensive written records from before the Bronze Age collapse have been very successfully translated. The two cultures were quite different from ours today, and from each other as well, but what they had in common was a rigid social hierarchy that functioned for millennia and that bound politics and religion tightly together. They were each, in fact, a theocracy dominated by ’gods’ in an elaborate polytheistic system with a correspondingly elaborate priesthood. The two systems were typical of two types of ancient kingdoms, which probably began out of similarly primitive bicameral origins but developed differently:

- the "steward-king theocracy [… of the] Mesopotamian bicameral city-states" appeared in some variety as "the most important and widespread form of theocracy [... in] Mycenae[, ...] and, so far as we know, in India, China, and probably Mesoamerica";[92]: 178-185

- the "god-king theocracy in which the king himself is a god" [is the "more archaic": 186 system that] "existed in Egypt and at least some of the kingdoms of the Andes, and probably the earliest kingdom of Japan."[92]: 178,186

Mesopotamia[edit]

The basic facts of Ancient Mesopotamian religion (or Sumerian religion) are fairly well-established from the archaeology and texts of the Sumerians and Akkadians. Shrines and statues of gods, mostly made of wood, were everywhere, and they were central to daily life.[92]: 178–179

Throughout Mesopotamia, from the earliest times of Sumer and Akkad, all lands were owned by gods and men were their slaves. Of this the cuneiform texts leave no doubt whatsoever. Each city-state had its own principal god, and the king [was] "the tenant farmer of the god."

The god himself was a statue. The statue was not of a god (as we would say) but the god himself. […] The gods, according to cuneiform texts, liked eating and drinking, music and dancing; they required beds to sleep in and for enjoying sex with other god-statues on connubial visits from time to time; they had to be washed and dressed, and appeased with pleasant odors; they had to be taken out for drives on state occasions; and all these things were done with increasing ceremony and ritual as time went on.

Jaynes asks:[92]: 180-184

How is all this possible, continuing as it did in some form for thousands of years as the central focus of life [...if not because of bicamerality?] Everywhere in these texts it is the speech of gods who decide what is to be done. […The] rulers [are] the hallucinated voices of the gods Kadi, Ningirsu and Enlil. [...And] statues underwent mis-pi which means mouth-washing, and the ritual of pit-pi or "opening of the mouth." [...] Each individual, king or serf, had his own personal god [and] lived in the shadow of his personal god, his ili [who was responsible for every action.]

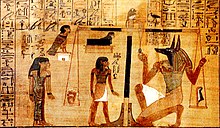

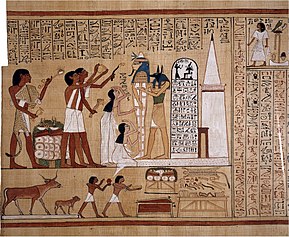

Egypt[edit]

Many basic facts of ancient Egyptian religion are similarly well-established, based on the successful decipherment of Egyptian texts in hieratic and hieroglyphics (meaning the "writing of the gods"). Egyptian beliefs and concepts are often stated in concrete terms, and Jaynes stresses that such straight-forward texts are often mis-interpreted and mis-translated to suit modern ways of thinking and philosophizing. For example, Jaynes refers to the creator god Ptah written about in the Memphite Theology, and comments:[92]: 186

. . . that the various gods are variations of Ptah’s voice or "tongue."

Now when "tongue" here is translated as something like the "objectified conceptions of his mind," as it so often is, this is surely an imposing of modern categories upon the texts.

Concerning the central mythology of the pharaohnic god-kings, "that each king at death becomes Osiris, just as each king in life is Horus[,]" Jaynes asserts:[92]: 187

Osiris [...] was not a "dying god," not "life caught in the spell of death," or "a dead god," as modern interpreters have said. He was the hallucinated voice of a dead king whose admonitions could still […] be heard, [therefore] there is no paradox in the fact that the body from which the voice once came should be mummified, with all the equipment of the tomb providing life's necessities: food, drink, slaves, women, the lot. There was no mysterious power that emanated from him; simply his remembered voice which appeared in hallucination to those who had known him and which could admonish or suggest even as it had before he stopped moving and breathing.

…and the process repeated from generation to generation.

The ka and ba[edit]

Jaynes agrees with mainstream scholarship that an important but confusing "fundamental notion": 189 in Ancient Egyptian religion is that of the ka. Jaynes observes:[92]: 190

. . . this particularly disturbing concept, which we find constantly in Egyptian inscriptions, [has been translated] in a litter of ways, as spirit, ghost, double, vital force, nature, luck, destiny, and what have you.

Texts about the ka are numerous and confusing. "Every person has his ka[. ...] Yet when one dies, one goes to one's ka.": 191 The Pharaoh and his ka, usually depicted as twins, are formed together at birth. Some texts, however, "casually say that the king has fourteen ka's!": 193 Bicamerally interpreted, the ka is "what the ili or personal god was in Mesopotamia.": 190 Pharaoh heard his ka while alive, while others would hear their own ka and would also hallucinate the Pharoah’s voice as the Pharaoh's ka, which could still be heard for some time after Pharaoh’s death.: 189–191

A related concept is that of the ba, which was usually depicted as a small humanoid bird associated with a corpse or statue of a person. The "famous Papyrus Berlin 3024, which dates about 1900 B.C." and records the "Dispute of a man with his Ba", has never been translated "at face value, as a dialogue with an auditory hallucination, much like that of a contemporary schizophrenic.": 193–194

Systemic social breakdown[edit]

Bicameral societies changed slowly over the millennia, but some changes, for example inter-cultural contact and trade, periods of expansive population growth, and natural calamities probably weakened the effectiveness of social control by the hallucinated divine beings.[44]: 206-217 While inherent instabilities made many bicameral theocratic kingdoms susceptible to collapse,: 207 only in the later millennia, after recurring breakdowns of bicameral authority, did the adaptive behavioral response of consciousness become possible; it eventually did occur, probably at different times and places.[44]: 216-222

Effects of writing[edit]

Human language and 'voices' evolved in connection to an auditory system in which the ears, unlike the eyes, cannot be closed; the hearing of sounds cannot be 'shut out'. The invention of writing, which relied on a visual system, connected language to a visual sign in a fixed location that could be looked at or avoided. Thus the use of writing was one factor that contributed to the eventual decline of the "authority of sound",: 94–97 and so of bicamerality. Originally, however, visual symbols were probably written on behalf of, and read by, the 'gods' of the right hemisphere, and the person looking at the text perhaps got the message more as "a matter of hearing […], that is, hallucinating the speech from looking at [written] picture-symbols[.]"[92]: 182

In Mesopotamia, the use of writing to encode 'divine law' (that is, the "judgement-giving") that was told to Hammurabi by his god (either Marduk or Shamash) probably enhanced the social order, at least at first.: 198–199 The practice of recording god-commanded events possibly helped the gods (i.e. the right hemisphere) remember and learn from their own past. The constant recitations and repetitions of such texts possibly produced culturally-defining epic poetry as a bicameral process. In the 1st millenium BCE, however, while the ancient texts remained as cultural artifacts, the bicameral recitation process eventually gave way to something different, supporting a major characteristic of consciousness, namely the individual's "ability to narratize memories into patterns[.]"[44]: 217-218

Loss of social order[edit]

"The smooth working of a bicameral kingdom has to rest on its authoritarian hierarchy.": 207 The admonitory functions of hallucination could respond to familiar and non-threatening situations, but might fail in unfamiliar or unmanageable situations. The success of civilized life increased the numbers of individuals' 'voices' that needed to be managed in order to maintain social order. Every established bicameral theocracy became polytheistic and had a hierarchy of priests to manage potential competition between the gods, i.e. the 'voices', of the pantheon. Many "such theocracies occasionally did [...] suddenly collapse without any known external cause.": 207 [c] Even the relatively stable bicameralities, such as in Egypt, never resolved polytheistic inconsistencies.[d] Over the course of many centuries, failures of hallucinatory authority required adaptation, or proved to be insurmountable:

- The psychological "authority of sound": 94–99 was gradually weakened, certainly by the mid-2nd millennium BCE, by the widespread use of written texts.: 209

- Inter-cultural contact between city-states, also as a result of growth, could either lead to trade relations or to conflict — but nothing in-between — depending on whether the gods on each side judged the other human as friend or foe. A judgement of the 'other' as hostile could easily lead to war, which certainly brought social chaos.: 205–207

- Besides war, natural catastrophes likely brought social chaos, followed either by long periods of rebuilding, or by migrations and potentially hostile contacts between individuals and populations.

Substitutes for divine authority[edit]

In the event of serious social disorder, "the gods could not tell you what to do[.]": 209 They became silent, or they produced more disorder.: 208–216 During the 3rd millennium BCE ancient Mesopotamian religion began to express the first forms of prayer rituals and sacrificial offerings, probably to invoke 'voices' that did not speak automatically in the face of a difficult problem.: 223–230 [e] Before consciousness could "narratize" (i.e. to 'tell the future') about an action and its consequences, a wide variety of divination rituals and the reading of omens became common practices to help a king, priest or other inquirer decide what needed to be done.[f] Eventually, and continuing into the 1st millennium BCE, Mesopotamian religion had created a superstitious world filled with countless angels and genii — beneficial half-human, half-bird messengers to the now 'distant' gods — plus countless demons, against whom protection was sought by the widespread use of amulets and exorcisms.: 230–233

The dawn of consciousness[edit]

The limited historical record of the late Bronze Age currently offers no more than clues to the possible dawn of consciousness.[11] By the end of the 3rd millennium BCE, the city owned by "Ashur" had risen to become a trading empire, Old Assyria. It collapsed but rose anew about 1380 BCE, becoming the 2nd Assyrian Empire, a militaristic, brutal conqueror unlike any before it. The new Assyrians encountered a chaos widespread throughout the region, with migrations of many peoples perhaps fleeing natural calamities. Jaynes asserted that the recorded unprecedented cruelty of the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I may have been a chaotic response to the total collapse of bicameral social order.

The very practice of cruelty as an attempt to rule by fear is, I suggest, at the brink of subjective consciousness.[44]: 214

Natural disasters "certainly accelerated" the collapse of bicamerality.: 212 Jaynes originally speculated that the major cause of collapse was a volcanic eruption:

Whenever it was, whether it was one or a series of eruptions, [the collapse of Thera] set off a huge procession of mass migrations and invasions which wrecked the Hittite and Mycenaean empires, [and] threw the world into a dark ages within which came the dawn of consciousness.: 213

By 1990, Jaynes deemphasized the volcano as an immediate cause of the "dark ages" because new evidence indicated that the Minoan eruption may have occurred, or begun, as early as 1600 BCE.[109] Even so, some historians writing after Jaynes have described the end of the millennium as the catastrophic 'Late Bronze Age collapse'. It was "a form of systems collapse [. . .that] requires a widespread internal fragility" and a "broad instability" for it to make sense, and Jaynes's theory may be the best way to explain it.[110]

Early centuries of transition to consciousness[edit]