User:Donald Trung/History of the manufacturing process of cash coins

This page serves as "the editing history" of the English Wikipedia article "History of the manufacturing process of cash coins" and is preserved for attribution.

"Upright casting" with piece moulds[edit]

The first form of metal casting in China dates back to the Shang dynasty and Western Zhou dynasty periods and was known as "Upright Casting" with piece moulds (板范豎式澆鑄),[1] this manufacturing technique would be used continually from the middle and later parts of the Spring and Autumn period of the Zhou period until as late as the Western Han dynasty.CAOJIN From the beginning coin casting was done at generalised bronze casting workshops that specialised in bronze objects and like the casting moulds of the aes the moulds used for early Chinese coinages were made of clay.[2][3][4]

The earliest cast coinages of China during this period weren't cash coins but different types of bronze coinages in various shapes such as the cowry shell-based Tong Bei, Spade money, Ant-nose coin, and round coins known as Huanqian.[2] The Spade Money coinages produced during this period functioned as a kind of link between familiar tools used in agriculture that were bartered and stylised objects that were used as a form of currency.[2] This was in parallel with the later created Knife money currency.[2]

The clay moulds would be used alongside stone and bronze moulds during the Warring States period which also saw the introduction of the first cash coins, namely the Ban Liang.[2] During the beginning of the Han dynasty period the production of cash coins wasn't monopolised by the central imperial government and both local governments as well as private manufacturers were known to produce cash coins.[2]

Different manufacturing techniques had different advantages and disadvantages, the formed and baked clay moulds that were commonplace before this era saw rising competition from stone moulds, this was because the carved moulds that were utilised were made of soft stones and they were were easily made and their creation was ad a lower cost because they could be utilised in coin production more than once, as opposed to stone moulds.[2] While they were better to use than clay moulds, stone moulds had the tendency to become brittle with ease during the casting process, so manufacturers would soon introduce bronze casting moulds.[2] This evolution was paired with larger interiors for the moulds so that they were capable of producing even more cash coins during a single casting session, during the early Western Han period these larger bronze moulds could produce as much as several dozens of cash coins at a time and unlike the earlier moulds they could be used much more often.[2]

The casting process in these early moulds worked in a way that two mould-sections were placed together, then the core of the mould was placed into the top area, then the bronze smiths would pour molten metal into an opening that was formed by a cavity that was located in its centre.[2][5][6][7]

"Stack casting"[edit]

"Stack casting" (疊鑄) is a method of cash coin casting where large quantities of identical coin moulds were placed together in a way that they were all connected to a single common casting gate, this allowed for a very large quantity of objects to be manufactured in only a single casting session, saving time, labour power, metal, materials for fuel, and refractory material.[2][8]

Historians still debate when the "stack casting" method was first used, some believe that it originated during the Warring States period while others than it started sometime during the Western Han dynasty period by commoners.[2][9] While some Ban Liang cash coins of the early Western Han dynasty period and the 4 zhu Ban Liang cash coins were produced using this method.[10] It wasn't until it was adopted by the imperial Chinese government during the Xin dynasty period, under the rule of Emperor Wang Mang,[11][12] that this technique would become the most common method for the production of cash coins.[2][13][14] The adoption of this casting method allowed for the government to produce more cash coins, as during the Xin dynasty a single cast could produce 184 cash coins, a number which wasn't possible to have been achieved with the earlier "Upright Casting" technique of manufacturing cash coins.[2] A 2004 simulation experiment managed to cast 480 coins during a single casting process with this technique.[2][15] From the Eastern Han dynasty period until the adoption of sand-mould casting this would be the main technique for casting bronze cash coins in China.[10]

The "stack casting" method would continue to be improved over the ages and was used in China until the end of the Southern dynasties during the Northern and Southern dynasties period.[2]

In China the "stack casting" method would be superseded by sand casting method for producing cash coins sometime during the 5th and 6th centuries, but the "stack casting" method endured in Vietnam until as late as the 19th century, as the French colonial authorities reported on the Nguyễn dynasty still using the "stack casting" method for producing cash coins until modern machine-struck cash coins were introduced.[2][16]

Sand casting method[edit]

The "sand casting method" (翻砂法) is a technique where cash coins were cast using vertically arranged two-piece moulds.[2] This technique allowed a large number of cash coins to be produced in batches.[2]

In the sand casting method the preparation of moulds was done with fine sand which was reinforced using an organic binder, and placed inside of a wooden box.[2] Consistency of the designs was maintained through the creation of "mother coins" (母錢), which were either individually produced or were identical copies of a single "ancestor coin" (祖錢).[2][17] Around 50 to 100 "mother coins" were pressed lightly into the surface of the mould box and was followed by the placing down of a second mould box on top of the first one.[2] This allowed for an impression to be taken of both sides of the pattern of the mother coin.[2] After the impression was taken the mould boxes would be turned over and separated, which would allow the mother coin to stay placed on the surface or the lower mould.[2] A new fresh mould box would subsequently be laid on top and this allowed the pair to be turned and separated again. Using this methodology, the mint workers obtained a series of two-piece moulds.[2] Afterwards, the casting channels between the cash coin imprints and a central tunnel were cleared out, allowing the boxes to be fixed together in pairs of two. The final step involved the pouring in of molten metal.[2]

When the process was done and the metal was allowed to cool down a "coin tree" was formed, from this "coin tree" the cash coins could be separated and cleaned up.[2][18]

Early history and origins[edit]

The origins of the sand casting method for manufacturing cash coins remain unknown.[2] Many scholars on the topic date the origins of sand casting to have started sometime during the Sui dynasty period, this is because it is around the Sui dynasty period that archeologists haven’t found any moulds that were used in for "stack casting" production method. Despite this, no written records back this common hypothesis up.[2] More recent archaeological finds note that sand casting has existed as early as the Northern Wei dynasty period.[2] The sand casting method relied on using matrix coins and sand moulds, because of this reason no moulds would be left-over after the coins were cast, making the technique different from earlier methods which had re-unable moulds.[2]

In China early sand casting utilised something called "Wiping the cash coins with a silk net", however, in China this would not appear in later sand casting production, while in Japan this technique remained in use until the Edo period, as a picture scroll depicting the manufacturing process of cash coins at the Ishinomaki Mint showed it still being in use.[2]

A Wu Zhu cash coin attributed to the Northern Wei period in the hands of the Shanghai Museum shows clear signs that it was manufactured using the sand casting method.[2][19]

In the year 1990 a coin tree was unearthed near the city of Xi'an, this coin tree was dated to the Northern Zhou period (557-581) showing that the sand casting method for producing cash coins is much older than scholars once thought, that before the find typically attributed its origins around the Sui dynasty period.[2] Later these findings would be backed up by a Tang dynasty coin tree found in the city of Baoji.[2]

In the year 2008 a Tang dynasty period cash coin manufacturing facility from the 7th century had been discovered in Guangzhou, Guangdong, this mint used the sand casting method and is further evidence for early usage of this casting technique.[2][19][20] According to the Wenxian Tongkao (文獻通攷), chapter 8 the city of Guangzhou was not among the four imperial government mints which were established during the early Tang dynasty period, meaning that the discovered site was likely the base of a large cash coin counterfeiting ring.[2]

Some scholars suggest that the usage of the sand casting technique for creating cash coins likely started not with official mints but with counterfeiting rings, this also means that these counterfeiters were using common circulating cash coins for producing more instead of the matrix coins, and that the sand casting method was utilised for practical purposes by commoners to produce cash coins in periods when the central government only enforced cash loose control over the production of currency.[2]

Song dynasty[edit]

The calligraphy found on the cash coins that were produced during the Song dynasty period is today regarded as a symbol of highest form "coin culture" or "coin art" throughout Chinese monetary history.[2] Today the cash coins of the Song dynasty are still widely regarded as the cash coins of the highest quality ever produced.[2]

During the early 11th century the Northern Song dynasty official Yu Jing (余靖) wrote a detailed description of the workings of the Yongtong Mint in Shaozhou,[a] which was established in the year 1048.[21][2] Yu Jing describes the mint as making moulds, smelting metals, and using files to file the coins, and then finishing off by using water to wash them.[2] His account describes that the Yongtong Mint had 8 workshops that were divided into 2 departments, which for each working process were further divided into 8 different sections, noting that the entire mint had a total of 800 rooms.[22][2] However, what each department and what each workshop was isn't described in the text.[2]

During the Southern Song dynasty period records about the iron cash coin mint in Qizhou (located in modern day Hubei province) state that the casting process was a 3 step method, the first step was done in the workshop of making sand moulds (沙模作) for the casting of iron cash coins itself, followed by the workshop of polishing cash coins (磨錢作) for the finishing of the freshly cast coins, and finally the workshop of arranging and ordering (排整作) for controlling the finished product.[23][2] These workshops were likely further divided into different specialised sections that each employed their own specialists.[2]

Yuan dynasty[edit]

During the period of Mongol domination under the Yuan dynasty metal currencies including cash coins didn't have a major role in the economy as paper money were was the main instrument of monetary policy.[2] Therefore information about cash coin casting during the Mongol period is scarce.[2]

Ming dynasty[edit]

The usage of cash coins again gained prominence following the establishment of the Ming dynasty.[2] Sources relating to the the manufacture of cash coins using the sand casting method have also been better preserved during the Ming period when compared to the earlier Song dynasty where only a handful of texts and mentions have survived.[2] For example, the Tiangong Kaiwu records a number of illustrations and detailed descriptions of the conditions of the sand casting process during the late Ming dynasty period.[2][24] The Tiangong Kaiwu describes that the first step in the sand casting process at the time was to create crucibles in which the copper would later be melted.[2] The melting process included a mixture of 3 parts charcoal powder and 7 parts crushed dry earth and brick fragments in order to boost the refractability.[2] This method of manufacturing crucibles was still being used as of 2015.[2][25]

The Tiangong Kaiwu lists that ox hoof-nails (牛蹄甲) was used in the production of crucibles, this ingredient was already known in traditional Chinese medicine and was mentioned in the Bencao Gangmu, the presence of ox hoof-nails does not appear in any later sources, rather salt would take the place of ox hoof-nails during the succeeding Qing dynasty period.[2] Both in traditional Chinese medicine and in the manufacture of crucibles the "ox hoof-nails" would first have to be burnt down to ashes before it could be used.[2] Modern chemical analysis of this ingredient shows that burnt ox hoof-nails have both calcium and sodium in large amounts.[2][26] This indicates that the usage of ox hoof-nails in the Ming dynasty period fulfilled the same role as salt would later do under the Qing.[2]

After the crucibles were done, the sand moulds would be prepared.[2] This preparation consisted of using 4 pieces of wood measuring 1.1 chi (尺) long (circa 35 cm) and 1.2 cun (寸) wide (circa 3.8 cm) to construct a square frame.[2] These square frames would then be filled and with finely screened earth and charcoal powder into a tight package, subsequently this would be sprinkled with either powdered charcoal of fir or of willow.[2] The wooden frame was used as a way to easily part the mould (demoulding) after the melting process was done.[2]

After the moulds were constructed the workers would enact a step known as smoking the moulds (薰模), which included them using burning resin and clear oil.[2] The moulds were smoked in order to cover them with a thin layer of what was called yanhei (煙黑, "soot black") which functioned to make reducing gas while casting, this technique helped with how the cash coins would end up.[2] This is because the surface of cash coins produced by smoked moulds were brighter and cleaner.[2][27]

The Tiangong Kaiwu then describes the process of filing and polishing cash coins after the cash coins were taken out of the moulds.[2] During the reign of the Jiajing Emperor this was done using lathes, while by the time that the Tiangong Kaiwu was written this was done by "several hundred cash coins that were strung on bamboo or wooden sticks and filed together".[24][2] The Taigong Kaiwu references a technique that was introduced at the Beijing Mint in 1562 in order to reduce the costs of coin production, to this end they replaced the lathes with files.[2] However, these cash coins, while cheaper to produce, weren't well received by the market and they were commonly referred to using the derogatory term yìtiáo gùn (一條棍) meaning "one stick".[2] These yìtiáo gùn were received by the common people with the same suspicion as counterfeit currency and many tradesmen and merchants would refuse to accept these coins when either the government or its employees tried to pay them using them.[2] Eventually, the imperial government would issue an edict that mandated the yìtiáo gùn to be accepted as a form of payment, this negatively affected the market causing both many merchant establishments and money shops to cease operations.[28][2]

The men who worked at the cash coin mints of the Ming dynasty were generally skilled labourers and craftsmen and not forced labourers, the Memorial of listed discussion on monetary policy (條議錢法疏) notes that the impoerial government had attempted to employ corvée labourers recruited from Minzhuang (民壯, "able-bodied commoners") and Shuifu (水夫, "water carriers") to be employed as grinding-coin-craftsman (磨錢匠).[2] These men typically didn't have any specialised skills and when they were tasked with operating the lathes it turned out that they didn't do it sufficiently leading to the rims of the cash coins not becoming even and smooth, resulting in the imperial government once again exclusively hiring skilled craftsmen for these jobs.[2][29]

Another specialty of coin finishing during the Ming dynasty was to lacquer the surfaces of cash coins, which created a special kind of cash coin known as Huoqi qian (火漆錢).[2] It remains disputed if this lacquering method was actually more cost effective than simply using a better alloy to produce coins.[2]

Qing dynasty[edit]

During the reign of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty the casting techniques employed during the preceding Ming dynasty would stay largely in place with fairly little changes happening throughout the period.[2] A notable difference between Ming and Qing casting techniques was the fact that the "smoking the moulds" step was no longer applied during the Qing, meanwhile the rest of the process would remain largely unchanged.[2] While the casting techniques would remain generally unchanged the organisation of the mints did change substantially with the cash coin minting system becoming more systematic.[2]

Tokugawa shogunate[edit]

In the Chinese Song dynasty period Rhapsody of the Great Smelting (大冶賦) published in the year 1210 the sentence "wiping the coins with a silk net" recorded, however, it wouldn't be until the Edo period that this process is mentioned again in any historical texts, notably in the Picture Scroll of Coin Casting, which details the production process of Kan'ei Tsūhō (寛永通寳) cash coins at the Ishinomaki Mint.[2] This indicates that this specific method may have disappeared in China but continued to be applied in Japan centuries after it stopped being used elsewhere.[2]

Machine-struck cash coins[edit]

Qing dynasty[edit]

French Cochinchina and French Indochina[edit]

Joseon[edit]

Production numbers[edit]

China[edit]

The production numbers of of cash coins throughout the monetary history of China had great variation.[2] The reasons for this varied due to both political and economic factors, including the the government's ability to create the infrastructure necessary to create cash coin mints.[2] For example, a lack of mint metal would reduce the ability and availability of the operation processes of mints.[2] Another important factor that played throughout Chinese history was governmental monetary policy and the level of importance that the dynasty placed on the production or cash coins as opposed to issuing paper money and/or silver ingots.[2]

List of average and peak cash coin production numbers in China by dynasty:[2]

| Dynasty | Average (period) | Peak (year) |

|---|---|---|

| Qin and Han dynasties | 220.000.000[30] | |

| Tang dynasty | 327.000.000 (739)[31] | |

| Northern Song dynasty | 5.000.000.000 (1078-1085)[32] | |

| Southern Song dynasty | 400.000.000 (1136)[33] | |

| Yuan dynasty | No notable cash coin production. | No notable cash coin production. |

| Ming dynasty | 500.000.000 (1630)[34] | |

| Qing dynasty | 3.590.000.000 |

Qin and Han dynasties production numbers[edit]

From 118 BC to 5 AD, the government minted over 28,000,000,000 cash coins, with an annual average of 220,000,000 coins minted (or 220,000 strings of 1,000 cash coins).[35]

Tang dynasty production numbers[edit]

The Tianbao period (天寶, 742–755 AD) of the Tang dynasty produced 327,000,000 coins every year.[35]

Song dynasty production numbers[edit]

The Song dynasty produced 3,000,000,000 cash coins in 1045 AD and 5,860,000,000 cash coins in 1080 AD.[35]

Ming dynasty production numbers[edit]

Vietnam[edit]

Nguyễn dynasty production numbers[edit]

Zeniza emaki[edit]

! Illustration !! Description

General differences between cash coins and other coinage types[edit]

Ever since the first coins were created many different concepts of defining coins, monopolisation of their production, and appreciation have been created that would lead to complex monetary systems arising in Eurasia.[2] Many of these different systems of coinages are similar and due to international contact have been transmitted mutually or have influenced each other in various ways over the centuries.[2] But of these complex different systems the most basic difference has survived between cash coins and other coinages, with only very few exceptions, until the end of the 19th century, namely their method of manufacture.[2] While the many coinages of Europe and West Asia were usually hammer-struck or later machine-pressed in contrast East Asian and Vietnamese cash coins were typically cast.[2][36]

Note that cast coinages did exist in Europe at times and even co-circulated with the struck coinages, but these European (Roman and Celtic) cast coinages were never as widespread as Far Eastern cast coinages.[2]

This difference wasn't minor and created more differences between the Far Eastern and Occidental coinage systems than the mere superficial.[2] These major differences included manufacturing techniques during their production, the working processes of the mints, az well as requirements of labour and organization in the coin mints.[2] This resulted in different quantities, quality, and levels of fineness of the coins leading to extremely different monetary and economic histories emerging in the different societies.[2] Other differences such as the rarity of silver and gold coinages circulating in Chinese society as opposed to many others also widened this divide as most cash coins were made from copper-alloys, namely leaded bronze and later different kinds of brass alloys.[2] When silver did emerge in China during the 10th to 16th centuries it was traded in weight and/or bullion rather than as an actual standardised coinage.[2] It wasn’t until as late as the 18th century that round silver coins would become a more widespread means of exchange during financial transactions, namely foreign silver coins that were imported into China through trade.[2]

Another major difference that existed between Far Eastern and Occidental coinages because of the difference in manufacturing process was the fact that the central government did not at all times seek to obtain a profit from casting cash coins but even produced them at a significant loss, this was done because of the widespread circulation of cash coins throughout the realm with the reign period of the Emperor on them as an inscription, this was seen as both a symbol of legitimacy and one of the political power of the Emperor.[2]

Problems of minting cash coins compared to other types of coinages[edit]

Cao Jin (曹晉), a researcher at the Department of Chinese and Korean Studies, Tübingen University, in her 2015 paper Mints and Minting in Late Imperial China: Technology, Organisation and Problems pointed out a number of problems that the casting of cash coins in China had when compared with the production methods of coinages in other countries.[2] Cao Jin notes that a good indicator for the economic productivity of coin minting can be found in the comparison of the overall production costs associated with coin minting when compared with the manufacturing costs.[2] According to Peng Xinwei, the percentage of manufacturing costs stood at a minimum of 9.77%, a maximum of 22.2%, and an average greater than 15% for Chinese cash coins during the reign of the Qing dynasty.[2] Cao Jin noted in her paper that the expenses that were endured by the process of casting raw mint metal into copper-alloy coins should not be neglected.[2]

She stated that if a government hoped to make a profit out off issuing coins that the value of the coin should not be exceeded by the costs of manufacturing as well as the costs of procuring the metals necessary for the minting (which includes the loss of material during both the smelting and casting processes).[2] These costs are lower for metals more precious than copper and the generally low cost of copper meant that the high cost of minting meant that production costs made profitability difficult.[2]

Cao Jin cites a number of manufacturing cost statistics in her research paper to compare the manufacturing cost ratios of hammer-struck European coinages to compare with contemporary Chinese cash coins:[2][37]

| Type of coinage | Manufacturing costs as percentage of value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Gold coins | 0.1% | Zhongguo huobi shi (中國貨幣史) (1965) by Peng Xinwei (彭信威). |

| Silver coins | 1.5% | Zhongguo huobi shi (中國貨幣史) (1965) by Peng Xinwei (彭信威). |

| Western copper coins | 3% | Zhongguo huobi shi (中國貨幣史) (1965) by Peng Xinwei (彭信威). |

| U.S. copper cent coins in 1831[b] | 5% | Report on Gold and Silver Coins, by United States Congress House (Washington D.C.: Gales and Seaton, 1810). |

| English copper coins struck from imported Swedish copper (Between 1672 and 1683) |

19.4% | The Mint: A History of the London Mint from A.D. 287 to 1948 (1953) by John Craig, page 276. |

| English copper coins struck from domestic copper (until 1718) |

15.9% | The Mint: A History of the London Mint from A.D. 287 to 1948 (1953) by John Craig, page 276. |

| English copper coins struck from domestic copper (1805) |

18.8% | The Mint: A History of the London Mint from A.D. 287 to 1948 (1953) by John Craig, page 276. |

Cao Jin notes that especially the numbers from England (a constituent country of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland) display the fact that the manufacturing cost ratios are difficult to compare when taking different time periods and different locations.[2] She explains that technology alone doesn't explain the differences in production costs as the increase of the ratio from 1718 to 1805 can be explained by the exploitation of large copper deposits in Wales during this period causing the price of copper in England to steeply decrease.[2][38] She further notes that the fact that there's incomparability between these two systems is due to fact that copper-alloy cash coins in China were the only state-sanctioned currency (as the state didn't produce any coinages made out of precious metals) meaning that their production had a unique importance, which wasn't the case in Europe and the Americas where copper coins were only supplemental to a large gold-based and silver-based currency system.[2]

While the striking and pressing process used in the Western world meant that the casting of copper coinages would have, under certain circumstances, have always been a bit cheaper than the more expensive casting process employed by the Chinese, prior to the Great Divergence, the overall economic discrepancy wasn't very obvious.[2] However, once the Great Divergence started and the far-reaching technological improvements made coin minting cheaper in the West the differences in manufacturing costs between China and the West became large.[2] However, Cao Jin notes that when comparing the casting cost ratio between China and the West is the protection against forgery is an easier and clearer aspect to evaluate the differences and the unique problems that the Chinese faced when compared to the West.[2]

The coin striking, or later pressing, in the West is likewise a very complex production system which generally required a higher level of specialised handicraft skills and expertise than the Chinese casting system.[2] Because the coining process used by European and American mints ascribed an important role to the die and its engraver, the coins produced using this method meant that it was difficult to reproduce coins by modelling them after common circulating coins.[2] Meanwhile, counterfeiting was significantly easier in China as it was possible counterfeit coins based on common circulation coins using the "sand casting" process.[2] Had the same method be employed for European coins then the end result would be too different to have been passable as genuine coinage.[2] This meant that European coin counterfeiters would have to manually attempt to imitate the original die itself.[2] Counterfeiting the original die was a particularly difficult task because of the artistry involved in the original die as well as the unique style of the creator.[2] During later periods the reproduction of European coin dies was especially difficult because they would be produced using a grand number of punches in a set that was exclusively available in only a single die engraving workshop.[2][39]

As the problem of rampant counterfeiting was more pervasive in the Chinese case, this was due to a coin counterfeiter being able to counterfeit cash coins by only needing a good circulation coin, have several sand moulds, and their own facility used for the smelting of metal.[2] The pervasiveness and ease of access of cash coin counterfeiting was so far that the Qianlong Emperor even publicly admitted that the quality of the forgeries made by the large-scale counterfeiter Zeng Shibao (曾石保) were superior to many of the cash coins produced by government-owned mints.[2][40]

The mints in China attempted to compensate the lack of complexity in the manufacturing process by expanding and paying special attention to the techniques that were employed to the finishing of cash coins, this meant that a large number of different procedures that occurred after the completion of the casting process, and at different times, included things like polishing, lathing, filing, lacquering, Etc.[2] in the hopes that cash coin counterfeiters, who typically were searching for fast monetary gains, would be discouraged from their illegal activities as the additional costs to make believable circulation cash coins would lessen the profitability of cash coin counterfeiting.[2] However, the end result was that not just counterfeiting had become more expensive, the additional procedures introduced to the already very labour-consuming casting process meant that the a large number of new working stages now became necessary for the casting process, leading to both the prolongation of the manufacturing process and increasing costs paired with decreasing levels of productivity.[2]

Another important point of comparison between the coin production of China and that of the West is the fact that there is an aspect of ambiguity concerning the progress and the regress of both mint operation and mint technology in China.[2] At different time periods in China, leading up to the Northern Song dynasty period, the quality and quantity of cash coins produced saw a certain level of steady increase which would eventually peak with an annual production of 6.000.000.000 cash coins.[2] Concurrently, it is a common opinion to see the cash coins produced by the Song dynasty to be the most superior cash coins both in terms of quality and in their quantity produced.[2] This means that after having reached its zenith during the Song, cash coin production generally saw a steep decline in both quality and the quantity of their production numbers to the point that cash coin production was completely abolished under the reign of the Yuan dynasty (Mongol Empire).[2] The post-Song dynasty period also saw a stagnation of cash coin mint techniques which would persist until the early 18th century with the large-scale exploitation of copper deposits that were found in southwestern China.[2]

Meanwhile, European minting technologies during this same time period saw their most important changes.[2] As the traditional striking technology found in the traditional European system already had a number of advantageous aspects over the casting technologies used in China, the technological developments that occurred during this time period both in the die engraving and in the creation and adoption of the screw press, leading to the mechanisation of the European coin minting process from 1530,[41] lead to European coin minting becoming superior in a large number of diverse aspects.[2] By the 16th century the superiority of the European coin minting process was evident in labour intensity, productivity, as well as the precision of coin striking to the point that believable forgeries became difficult to produce.[2]

These differences would lead to the Viceroy of Liangguang, Zhang Zhidong, ordering the British company Ralph Heaton & Sons to set up a new machine mint in the Guangdong capital city of Guangzhou in 1887.[2] This new machine mint had a daily output of 2.600.000 copper-alloy coins and 100.000 silver coins employing 90 screw presses using the latest technology.[2] During the late 19th century the Guangzhou Mint was the largest mint in the world.[2][42] The success of the adoption of the European mechanised model by the Guangdong Province caused other Chinese provinces to follow the Cantonese example and by the closing years of the 19th century the entire Chinese minting system had been transformed, ending the differences between coin production in China and the West.[2][43]

Alloys[edit]

Research by the British Museum found that cash coins were always leaded, the usage of leaded copper was found to be present in both bronze and brass alloys.[2] Though the research indicated that the percentages of lead was remarkably lower in the brass alloys from the early 16th century onwards.[2] An analysis of the lead content in Chinese cash coins from history revealed that the lead content typically ranges from 10% to 20%, with the highest recorded lead percentage being found in 12th and 13th century bronze cash coins standing at 30% (which occurred during a time period of severe copper scarcity).[2] Meanwhile, the percentage of lead found in brass cash coins was on average 5%, typically ranging from 2% to 8%.[2][44] Cao Jin (曹晉), a researcher at the Department of Chinese and Korean Studies, Tübingen University, pointed out that there were mainly 2 reasons for this, one of which was economic and the other technical.[2] She noted that the addition of lead was cheaper than other metals such as tin, zinc, or using more copper as lead was relatively cheap compared to other metals.[2] Furthermore, she noted that the technical reason was because of the fact that the addition of lead to copper-alloys boosted the fluidity of the melt, which facilitated the manufacturing process and qualitatively helped to improve the end result.[2] Cao Jin further argued that a lower percentage of lead during later periods can be attributed to the fact that only 3% lead is needed in a copper-alloy for a desired level of fluidity, concluding that the presence of high percentages of lead can mostly be attributed to economic reasons for the earlier cash coins and for technical reasons during later periods when copper scarcity was less of an issue.[2]

Ming dynasty period alloys[edit]

Until 1505 the main copper-alloy used for the manufacture of cash coins was bronze, but afterwards it was brass. This was a very important novelty in the monetary history of China.[2] This change remained in place after the fall of the Ming dynasty and brass was used until the 19th century.[2]

Numbers of mint employees[edit]

Song dynasty period mint employee statistics[edit]

During the Northern Song dynasty coin mints typically had several hundred workers, while the largest coin mint had around 1000.[2] Meanwhile, during the Southern Song dynasty these numbers had dwindled to between a few dozen workers to about 300 workers.[45][2]

Qing dynasty period mint employee statistics[edit]

In 1730, the Zhejiang Provincial Mint (寶浙局) had a total of 5 furnaces and employed 47 craftsmen per furnace, meaning that there were a total of 235 mint employees.[2][46] In 1740, the number of craftsmen employed per furnace had declined to 41, but the number of furnaces in operation doubled to 10, meaning that the Zhejiang Provincial Mint now employed a total of 410 men, with an annual production of 129,600 strings of cash coins.[2][47]

Between 1739 and 1747, the Sichuan Provincial Mint (寶川局) employed a total of 315 craftsmen and 15 furnaces.[2][48][49] Between 1755 and 1882 the Sichuan Provincial Mint operated 40 furnaces, meaning that the mint must've employed a total of 840 men.[2][49]

Numbers of mint workers and furnaces during the High Qing era:[2]

| Year | Mint | Number of employees | Number of furnaces | Workers per furnace | Annual strings of cash coins produced |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1730 | Zhejiang Provincial Mint (寶浙局) | 235 | 5 | 47 | |

| 1740 | Zhejiang Provincial Mint (寶浙局) | 410 | 10 | 41 | 129,600 |

| 1739-1747 | Sichuan Provincial Mint (寶川局) | 315 | 15 | 21 | |

| After 1755 | Sichuan Provincial Mint (寶川局) | 850 | 40 | 21 | 194,133 |

| 1797 | Guizhou Provincial Mint (寶黔局)[c] | 50 | 5 | 10 | 24,000 |

Number of cash coins produced per craftsman[edit]

The efficiency of a single cash coin mint workers at different periods in Chinese history is difficult to determine for a variety of reasons.[2] The calculations put forth by modern scholars in the field of Chinese numismatics are based a number of distinct factors and standers, which in particular concern the diversity of cash coins produced and different jobs of the mint employees that are counted in the statistics.[2] The availability of the data of the average production output of the individual cash coin mint worker is thus only valuable to provide a general idea of the overal productivity of the mint and isn't suitable as a marker for any actual developments.[2]

Number of cash coins produced per craftsman during the Tang dynasty[edit]

During the Tianbao reign era (天寶, 742–756) during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong, one worker, on average, manufactured over 300 cash coins per day.[2][50]

Number of cash coins produced per craftsman during the Song dynasty[edit]

- Between the years 974 and 1020 in accordance with the Guojia zhi zhi (國家之制), or the Imperial Standard, one mint worker had to produce a daily amount of over 1000 cash coins.[2][51]

- During the Tianxi reign-period (天禧, 1017–1021) under the reign of Emperor Zhenzong and the Tiansheng reign-period (天聖, 1023–1032) under the reign of Emperor Renzong, an average mint worker was expected to produce between 800 and 900 cash coins a day.[2]

- During the Xining reign-period (熙寧, 1068–1077) under the reign of Emperor Shenzong, an average mint worker was expected to produce between 1300 and 1400 cash coins a day.[2][52]

- Around the year 1225, the number for iron cash coins produced by an individual mint worker was 3333 coins.[2][53]

Number of cash coins produced per craftsman during the Ming dynasty[edit]

During the reign of the Hongwu Emperor (1368–1398), government regulations stipulated the following daily production per craftsman:[2]

| Type of cash coin | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Nominal value (in Zhiqian) |

Quantity of cash coins cast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xiaoping qian[d] | 小平錢 | 小平钱 | Xiǎopíng qián | 1 wén | 630 |

| Zhe'er qian | 折二錢 | 折二钱 | Zhé èr qián | 2 wén | 324 |

| Dangsan qian | 當三錢 | 当三钱 | Dāng sān qián | 3 wén | 234 |

| Dangwu qian | 當五錢 | 当五钱 | Dāng wǔ qián | 5 wén | 162 |

| Dangshi qian | 當十錢 | 当十钱 | Dāng shí qián | 10 wén | 126 |

| Total: | 1476 | ||||

Meanwhile the imperial government regulations for polishing craftsmen stated that they should polish twice the amount per day as a casting craftsman did, meaning that a single polishing craftsman was expected to polish 2952 cash coins during the Hongwu era.[2][54]

From the middle of the Ming dynasty period onwards written records on the daily productivity of individual craftsmen were no longer kept, instead now using the Mao (卯), or "casting period", as the main unit of mint productivity.[2] As the work and labour division of the cash coin mints were more organised over the time the production of cash coins was increasingly seen as a workplace-wide cooperation rather than the individual performance of a single craftsman.[2]

Organisation and salaries of mint employees[edit]

Ming dynasty period labour division and salaries[edit]

Pan Jixun, a Ming dynasty period scholar-bureaucrat, in his memorial concerning the country's monetary policy mentioned a number of types of mint employees and their salaries, these include:[2][55]

| Title | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Salary (for every 1,100 cash coins cast) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mint workers involved in the casting process | ||||

| Turning-sand-craftsman | 翻砂匠 | 翻砂匠 | Fānshā jiàng | 0.132 tael of silver |

| Watching-fire-craftsman | 看火匠 | 看火匠 | Kàn huǒ jiàng | 0.132 tael of silver |

| Lifting-crucible-craftsman | 提罐匠 | 提罐匠 | Tí guàn jiàng | 0.132 tael of silver |

| Mint workers involved in the polishing process | ||||

| Grinding-coin-craftsman | 磨錢匠 | 磨钱匠 | Mó qián jiàng | 0.088 tael of silver |

| Opening-characters-craftsman | 開字匠 | 开字匠 | Kāi zì jiàng | 0.088 tael of silver |

| Polishing-holes-craftsman | 銼眼匠 | 锉眼匠 | Cuò yǎn jiàng | 0.088 tael of silver |

| Piercing-stick-craftsman | 穿條匠 | 穿条匠 | Chuān tiáo jiàng | 0.088 tael of silver |

| Smoking-colour-craftsman | 熏色匠 | 熏色匠 | Xūn sè jiàng | 0.088 tael of silver |

| Total: | 0.836 tael of silver | |||

Based on the labour costs for these two processes, the salary of an employee directly involved in the casting process compared to that of one involved in the polishing process revealed a payment ratio of 6:4.[2] This difference in salary between the 2 different categories of mint workers attributes, to a certain extent, the intensity of the labour as well as the importance of each process to the end product of the mint.[2]

Later records mention a number of different types of cash coin mint employees, while a number of employee titles referenced by Pan Jixun aren't mentioned anymore.[2] These include, for example, "cash-stringer" (綑錢人) mentioned in the Chun ming mengyu lu (春明夢餘錄) as well as the "copper-smelter" (焺銅質) and "coin-model-engraver" (雕錢模) mentioned in the Record of economy of the Dynasty (國朝經濟録) by Zhang Pu (張溥).[2][56][57] The fact that these different professions of mint employees and craftsmen existed during the Ming dynasty period indicates that the cash coin mints did employ a form of organisation and labour division.[2] However, it was probably not as standardised and systematised as it would be under the subsequent Qing.[2]

Qing dynasty period labour division and salaries[edit]

The reign of the Qing dynasty saw the increasing standardisation of both the labour organisation and labour division of the cash coin mints.[2] While largely based on the Ming dynasty period working experience, the Qing mints employed 3 different types of workers and eight respective steps of labour per government regulations enacted in the year Qianlong 6 (1741).[2]

List of employees and salaries during the Qing dynasty:[2][58][59][60]

| Title | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Salary (Ministry of Revenue Mint, 1743) |

Salary (Ministry of Revenue Mint, 1769) |

Salary (Zhili Mint, 1769) |

Percentage of wages (1769)[e] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Watching-fire-craftsman | 看火匠 | 看火匠 | Kàn huǒ jiàng | 3 chuàn 264 wén | 3 chuàn 264 wén | 3 chuàn 264 wén | 13.90% |

| Turning-sand-craftsman | 翻砂匠 | 翻砂匠 | Fānshā jiàng | 5 chuàn 280 wén | 4 chuàn 400 wén | 4 chuàn 400 wén | 18.74% |

| Brushing-ash-craftsman | 刷灰匠 | 刷灰匠 | Shuā huī jiàng | 1 chuàn 848 wén | 1 chuàn 800 wén | 1 chuàn 800 wén | 7.67% |

| Miscellaneous-work-craftsman | 雜作匠 | 杂作匠 | Zá zuò jiàng | 3 chuàn 264 wén | 3 chuàn 4 wén | 3 chuàn 4 wén | 12.80% |

| Filing-edge-craftsman | 銼邊匠 | 锉边匠 | Cuò biān jiàng | 1 chuàn 872 wén | 1 chuàn 600 wén | 1 chuàn 600 wén | 6.82% |

| Rolling-edge-craftsman | 滾邊匠 | 滚边匠 | Gǔnbiān jiàng | 1 chuàn 680 wén | 1 chuàn 680 wén | 1 chuàn 680 wén | 7.16% |

| Grinding-coin-craftsman | 磨錢匠 | 磨钱匠 | Mó qián jiàng | 6 chuàn 720 wén | 6 chuàn 720 wén | 6 chuàn 720 wén | 28.63% |

| Washing-hole-craftsman | 洗眼匠 | 洗眼匠 | Xǐyǎn jiàng | 1 chuàn 8 wén | 1 chuàn 8 wén | 1 chuàn 8 wén | 4.29% |

| Total: | 24 chuàn 936 wén | 23 chuàn 476 wén | 23 chuàn 476 wén | 100% | |||

Besides the above craftsmen, cash coin mints also included another group of employees known as "furnace heads" (爐頭), these usually fulfilled a managerial role and their salaries were usually also included in the overall calculations of government regulations for the production costs.[2] "Furnace heads" largely acted as administrators and supervisors and their labour wasn't technical in nature.[2][61]

While the above model was the standard imperial government regulations for the labour division to be used throughout the Qing Empire, provincial mints would base their mode of operations on these regulations but might adjust them to their own in-house needs and regulations.[2] Many Qing dynasty period provincial mints diversified their cash coin production processes further than the official empire-wide regulations.[2] For example, the Guilin Mint (寶桂局), operating in the city of Guilin, Guangxi Province, had over 10 different types of craftsmen employed in the minting process.[2][62] The Zhejiang Provincial Mint (寶浙局), operating in the city of Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, between the years 1730 to 1740 had as much as 22 different categories of craftsmen employed throughout the minting process.[2][63] The Guilin Mint employed a total of 10 craftsmen per furnace and operated a total of 5 furnaces, meaning that the mint employed a total of 50 employees with an annual output of 24,000 strings of cash coins.[2][62][64]

During the Qing dynasty period the level of detailed specialisation lead to both greater standardisation and unification of mint standards and quality when compared to earlier dynasties in Chinese history.[2] However, this was only partially achieved as as differences between the various local mints still persisted throughout the reign of the Qing.[2]

General glossary of the manufacturing process of cash coins[edit]

General terminology[edit]

- String of cash coins (貫 / 索 / 緡 / 吊 / 串), refers to a

- Mao (卯),

- Ding (錠), a unit of account referring to 5,000 cash coins.ZHIQIAN

- Sapèquerie, French for "cash coin mint" (Note: sapèque is French for "cash coin").

Production process[edit]

- Moqian (磨錢), the grinding of cash coins, this was the most labour-intensive work in the mint and a part of the after-casting process.[2] As this was the part of the process that had the largest effect on the end quality of the cash coins meaning that cash coins produced by imperial governmental mints superior to the counterfeited ones, government-employed "grinding-coin-craftsmen" (磨錢匠) were typically the highest paid employees in the process.[2]

Salaries and production costs[edit]

- Salaries

- Lüfenqian (率分錢), or "percentage coins", was a type of payment given to mint employees during the Song dynasty.[2] During this period mints had 4 kinds of workers, these included skilled craftsmen, unskilled workers, soldiers, and prisoners.[2] This meant that the labour organisation of Song dynasty mints costed both of free (匠) salaried employees and forced labour (役).[2] Only a limited number of records from this period have survived into the present day and the only mention of salaries of this period notes that mint workers both had holidays and received this as a part of their payment.[65][2]

- Production costs

- Qianben (錢本), or "coin capital", refers to the overall costs of casting cash coins.[2] The authoritative regulation of the Qing dynasty, the Imperially Endorsed Collected Statutes of the Great Qing Dynasty (欽定大清會典) divides these costs into 3 categories: the procurement of the metal for minting, the costs of transportation, and the collective costs of labour (salaries), administrative tasks, as well as "all other necessary materials" (this includes fuel, salt, sand, crucibles, Etc.).[2] The final category is often named Gongliaofei (see below) in a number of sources and counted as a single category.[2]

- Gongliaofei (工料費), translated into English as either "costs for labour and material" or simply "casting cost", refers to the "miscellaneous" category of the Qianben.[2] During the Qing dynasty period the percentage of the Gongliaofei as a part of the Qianben was on average above 15% and ranged from as low as 9.77% to as high as 22.2%, according to research by the scholar Peng Xinwei.[2][66] According to the researcher Cao Jin, this large variation is possibly explained by the various types of both free and forced labour, as well the overall level of wages at the mint, the location of the mint, and the costs of fuel which varied strongly.[2]

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Yongtong (永通) literally means "eternal thoroughness".

- ^ If the copper could already be delivered in disc-shaped pieces.

- ^ Also known as the Guiyang Prefectural Mint (貴陽府局).

- ^ Also known as Xiaoqian (小錢), meaning "small money".

- ^ Percentage of wages to be spent on different types of mint workers according to the imperial regulation set up in the year Qianlong 34 (1769).

References[edit]

- ^ Tang Wenxing (湯文㠸) - ‘Woguo gudai jizhong huobi de zhuzao jishu’ (我國古代幾種貨幣的鑄造技術) [Coin-casting techniques of ancient China], in Zhongyuan wenwu (中原文物) [Cultural relics from the central plains], 2 (1983), pp. 74–78.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq cr cs ct cu cv cw cx cy cz da db dc dd de df dg dh di dj dk dl dm dn do dp dq dr ds dt du dv dw dx dy dz ea eb ec ed ee ef eg eh ei ej ek el em en eo ep eq er es et eu ev ew ex ey ez fa fb fc fd fe ff fg fh fi fj fk fl fm fn fo fp fq fr fs ft fu fv fw fx fy fz ga gb gc gd ge gf gg gh gi gj gk gl Cite error: The named reference

Cao-Jin-Cash-coin-castingwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Crawford, Michael Hewson. - Roman Republican Coinage, Vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974). Page: 589.

- ^ Hai-ping Lian, Zhong-ming Ding, and Xiang Zhou - Clay molds for casting metal molds used in minting techniques in the Han Dynasty Sciences of Conservation and Archaeology 24 (Supplement), 87-97.

- ^ Peng Xinwei (彭信威). - Zhongguo huobi shi (中國貨幣史, "A history of Chinese currency") – Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 1965. Page: 41. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- ^ Glahn, Richard von. - Fountain of Fortune: Money and Monetary Policy in China, 1000-1700 (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1996). Page: 48.

- ^ Vogel, Hans Ulrich. ‘Chinese Central Monetary Policy, 1600-1844’, in Late Imperial China, 8/2 (1987), pp. 1-52. Wagner, Donald B. Ferrous Metallurgy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008). Page: 15.

- ^ Wagner 2008, p. 154.

- ^ Hua Jueming 1983, p. 242-246.

- ^ a b Hai-ping Lian, Zhong-ming Ding, Xiang Zhou, and Hui-kang Xu - Study on the stack-casting techniques for casting coins of the Han Dynasty in China Sciences of Conservation and Archaeology 20 (Supplement), 53-61. Quote: "The stack - casting was used for casting the Banliang coins of the early Western Han Dynasty (206B.C.-A.D. 8) and the bronze coins of the Xin Empire (A.D. 9-23 ) and the Eastern Han Dynasty (A.D. 23-220) . It was a main technique for casting bronze coins from the Eastern Han to the time that the sand-mold casting was used. Some Banliang coins of the early Western Han Dynasty and Sizhubanliang coins of the middle Western Han Dynasty were also cast by the stack-casting. But Wuzhu coins were not found to be cast by the stack - casting technique."

- ^ Han Shiyuan (韓士元) - ‘Xin Mang shidai de zhu bi gongyi tantao’ (新莽時代的鑄幣工藝探討) [The technique of coin-casting in the Wang Mang period]. in Kaogu (考古) [Archeology], 5 (1965), pp. 243–251.

- ^ Li Gongdu (李恭篤) - ‘Liaoning Ningcheng xian Heicheng gu cheng Wang Mang qian fan zuofang yizhi de faxian’ (遼寧寧城縣黑城古城王莽錢范作坊遺址的發現) [A coin-mould worshop of the Wang Mang period at the site of ancient Heicheng in Ningcheng district, Liaoning], in Wenwu (文物) [Cutural relics], 12 (1977), pp. 34–43.

- ^ Shaanxi sheng bowuguan (陝西省博物館) - ‘Xi'an beijiao xinmang qianfan jiao zhi qingli jianbao’ (西安北郊新莽錢范窖址清理簡報, "A briefing of sorting out the ancient oven of making coins moulds during the Xin period (9-23AD) at the suburb north to Xi'an"), in Wenwu (文物, "Cutural relics"), 11 (1959), pp. 12–13. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- ^ Zhou Weirong (周衛榮) - ‘Zhongguo chuantong zhuqian gongyi chutan’ (中國傳統鑄錢工藝初探) [A primary research of Chinese-traditional coin-cast techniques], in Zhongguo qianbi lunwen ji (中國錢幣論文集) [A collection of papers on Chinese numismatics], 4 (2002), pp. 198–214. Zhou Weirong (2002a), pp. 13-20. 14

- ^ Dai Zhiqiang (戴志强), Zhou Weirong (周衛榮), Shi Jilong (施繼龍), Dong Yawei (董亞巍), and Wang Changsui (王昌燧). - ‘Xiao Liang qianbi zhuzao gongyi yu moni shiyan’ (蕭梁錢幣鑄造工藝模擬驗) [The coinage casting technique of the Liang Dynasty in the Six Dynasties and its simulation experiment], in Zhongguo qianbi (中國錢幣) [Chinese numismatics], 3 (2004), pp. 3-9. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- ^ Schroeder, Albert. - Annam: études numismatiques (Paris: Imprimerie nationale, E. Leroux, 1905). Pl. XXIV, XXV. (in French).

- ^ Zheng Jiaxiang (鄭家相) and Zeng Jingyi (曾敬儀) - ‘Lidai tongzhi huobi yezhu fa jianshuo’ (歷代銅質貨幣冶鑄法簡說) [A brief introduction to the methods of casting copper coins in the history], in Wenwu (文物) [Cutural relics], 4 (1959), pp. 68–70. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- ^ Sheridan Bowman, Michael Cowell and Joe Cribb. "Two thousand years of coinage in China: an analytical survey" in Wang, Helen et al. (eds.) (2005). p. 5.

- ^ a b Zhou Weirong 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Li Xiang et al. 2008, p. 11-15.

- ^ Xu zizhi tongjian changbian (續資治通鑒長編), vol. 165, p. 3969. (in Classical Chinese).

- ^ Wuxi ji (武溪集). chap. 15. (in Classical Chinese).

- ^ Youhuan jiwen (游宦紀聞), chap. 2, p. 16. (in Classical Chinese).

- ^ a b Sun, E-tu Zen, and Sun Shiou-chuan. T’ien-Kung K’ai-Wu: Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century, by Sung Ying-Hsing. (University Park and London: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1966), pp. 166-169.

- ^ Hua Jueming et al. 1999, p. 262-269.

- ^ Wu luling (武露淩), Chen Jianwei (陳建偉), and Wang Chungen (王春根) - ‘Zhu, niu, yang tijialei yaocai zhong wuji yuansu fenxi bijiao’ (豬、牛、羊蹄類藥材中無機元素分析比較) [Comparative analysis of anorganic components in pig, ox and sheep hooves as materia medica], in Jiceng zhongyao zazhi (基層中藥雜誌) [Basic Chinese medicine journal], 3 (1998), p. 45. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- ^ Hua Jueming (華覺明) and Zhu Yinhua (朱寅華) - ‘Muqian fa ji qi zaoxing gongyi moni’ (母錢法及其造型工藝模擬) [Matrix coin method and simulation experiment of its moulding technology], in Zhongguo keji shiliao (中國科史料) [China historical materials of science and technology], 3 (1999), pp. 262–269. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- ^ von Glahn 1996, p. 105.

- ^ Pan Sikong zoushu (潘司空奏疏), chap. 5. ‘Tiaoyi qianfa shu’ (條議錢法疏) [Memorial of listed discussion on monetary policy].

- ^ Hartill 2005, p. 85.

- ^ Hartill 2005, p. 103.

- ^ Hartill 2005, p. 125.

- ^ Hartill 2005, p. 160.

- ^ Hartill 2005, p. 237.

- ^ a b c Nishijima 1986, p. 588.

- ^ Tylecote, Ronald Frank - The Early History of Metallurgy in Europe (London; New York: Longman, 1987).

- ^ The Mint: A History of the London Mint from A.D. 287 to 1948 by John Craig (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1953), page 276.

- ^ Cooper, Tim - How to Read Industrial Britain? (London: Ebury press, 2011). Page: 54f.

- ^ Stahl, Alan M. - Zecca. The mint of Venice in the Middle Ages (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press in association with the American Numismatic Society, New York, 2000). Page: 237.

- ^ Cao Jin and Hans Ulrich Vogel - ‘Smoke on the mountain: the infamous counterfeiting case of Tongzi district, Guizhou province, 1794’ in Jane Kate Leonard and Ulrich Theobald (eds.) Money in Asia (1200-1900): Small Currencies in Social and Political Contexts (Leiden: Brill, 2015), pp. 188-219.

- ^ Tylecote, Ronald Frank - A History of Metallurgy (London, 1992). Page: 91.

- ^ Sweeny, James O. A Numismatic History of the Birmingham Mint. (Birmingham: The Mint, 1981). Chapter: X.

- ^ Reed, Christopher A. - Gutenberg in Shanghai: Chinese Print Capitalism, 1876-1937 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2009). Page: 313.

- ^ Michael Cowell, Joe Cribb, Sheridan Bowman and Yvonne Shashoua. The Chinese Cash: Composition and Production in Wang, Helen et al (ed.) (2005), p. 63.

- ^ Wang Shengduo (汪圣鐸) - Liang Song huobi shi (兩宋貨幣史) [Monetary history of the Song Dynasty] (Beijing: Shehui kexue wenxian chubanshe. 2003), pp. 119-120.

- ^ [Qianlong] Hangzhou fuzhi ([乾隆]杭ᐎ府志) [Gazetteer of Hangzhou prefecture]. Shao Jinhan 邵晉涵 et al. (comp.), 1784. Chap. 36, page: 14

- ^ Tongzheng bianlan (銅政便覽) [A manual on copper administration], collected by National Science Library, Chinese Academy of Sciences, hand written copy of Yunnan Provincial Administration Commission, 8 vols. Chapter 4.

- ^ Hartill 2005, p. 294.

- ^ a b Cao Jin 2012, p. 215.

- ^ Wang Shengduo (汪圣鐸) - Liang Song huobi shi (兩宋貨幣史) [Monetary history of the Song Dynasty]. (Beijing: Shehui kexue wenxian chubanshe. 2003). Page: 135.

- ^ Wang Shengduo (汪圣鐸) - Liang Song huobi shiliao huibian (兩宋貨幣史料彙編) [A source compilation of the monetary history of the Song Dynasty] (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2004). Page: 50.

- ^ Longchuan lue zhi (龍川略志) [Brief jottings of Dragon-stream] by Su Zhe (蘇轍) in 1099 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1982), chap. 3, p. 14.

- ^ Wang Shengduo (汪圣鐸) - Liang Song huobi shi (兩宋貨幣史) [Monetary history of the Song Dynasty]. (Beijing: Shehui kexue wenxian chubanshe. 2003). Page: 136.

- ^ Ming huidian (明會典) [Collected statutes of the Ming Dynasty]. Shen Shixing (申時行) (ed.), 1587, in Xuxiu siku quanshu (續修四庫全書). - (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1995), chapter 194, pp. 11a-12a.

- ^ Pan Sikong zoushu (潘司空奏疏), chap. 5. ‘Tiaoyi qianfa shu’ (條議錢法疏) [Memorial of listed discussion on monetary policy].

- ^ Chun ming mengyu lu (春明夢餘錄), chap. 38, p. 670.

- ^ Zhang Pu (張溥) - ‘Guochao jingjilu’ 國朝經濟録 [Record of economy of the Dynasty],in Qinding xu wenxian tong (欽定續文獻通攷), chap. 11.

- ^ Qingchao wenxian tongkao (清朝文獻通考), chap. 16, pp. 26-27. In the 3rd = year of Yongzheng reign-period (1725), the first step, i.e. “watching-fire” was still called “red furnace” (紅爐), or "Honglu". See vol. 15. The final step mentioned also has other varieties, e.g. xiqian (細錢) in Tongzheng bianlan (銅政便覽) and Qinding Hubu guzhu zeli (欽定戶部鼓鑄則例), Baoquanju mint (寶泉局), chuanqian (穿錢) in Baozhiju mint (寶直局).

- ^ Qinding hubu guzhu zeli 欽定戶部鼓鑄則例 [Imperially endorsed regulations and precedents for minting of the Ministry of Revenue], Fu Heng (傅恒) et al. (comp.). 1769 (Haikou: Hainan chubanshe, 2000 reprint, Gugong zhenben congkan, 287).

- ^ Peng Zeyi (彭澤益). Zhongguo jindai shougongye shi ziliao (中國近代手工業史資料) [Materials on modern Chinese handicraft history] (Beijing: Sanlian shudian, 1957). Page: 119.

- ^ Vogel, Hans Ulrich. ‘Unrest and Strikes at the Metropolitan Mints in 1741 and 1816 and their Economic and Social Background’ in Moll-Murata, Christine et al. (eds.) (2005), pp. 395-422.

- ^ a b Guangxi tongzhi (廣西通志) [Gazetteer of Guangxi province]. Xie Qikun (謝啟昆) (ed.), 1800. Chap. 178, p. 10.

- ^ [Qianlong] Hangzhou fuzhi ([乾隆]杭ᐎ府志) [Gazetteer of Hangzhou prefecture]. Shao Jinhan 邵晉涵 et al. (comp.), 1784. Chap. 36, pp. 14-15.

- ^ Tongzheng bianlan (銅政便覽) [A manual on copper administration], collected by National Science Library, Chinese Academy of Sciences, hand written copy of Yunnan Provincial Administration Commission, 8 vols. Chapter 5.

- ^ Wang Shengduo (汪圣鐸) - Liang Song huobi shi (兩宋貨幣史) [Monetary history of the Song Dynasty] (Beijing: Shehui kexue wenxian chubanshe. 2003), pages: 129-130.

- ^ Peng Xinwei (彭信威) - Zhongguo huobi shi (中國貨幣史) [A history of Chinese currency] (Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 1965). Page: 536.

Sources[edit]

- Cao Jin (曹晉) - Mint Metal Mining and Minting in Sichuan, 1700-1900: Effects on the Regional Economy and Society. (Ph.D. dissertation, Tübingen University, Tübingen, 2012).

- Hartill, David (2005). Cast Chinese Coins. Trafford, UK.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Nishijima, Sadao (1986), "The Economic and Social History of Former Han", in Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.), Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 545–607, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

External links[edit]

Category:Cash coins Category:Chinese numismatics

More sources to use[edit]

- https://www.academia.edu/25740794/Mints_and_Minting_in_Late_Imperial_China_Technology_Organisation_and_Problems

- <ref name="Cao-Jin-Cash-coin-casting">{{cite web|url= https://www.academia.edu/25740794/Mints_and_Minting_in_Late_Imperial_China_Technology_Organisation_and_Problems|title= Mints and Minting in Late Imperial China Technology Organisation and Problems.|date=2015|accessdate=29 April 2020|author= Cao Jin (曹晉)|publisher= [[Academia.edu]]|language=en}}</ref>

Zeniza emaki (Documentation)[edit]

Zeniza emaki (First attempt)[edit]

The description below follows selections from the Zeniza emaki ("Cash Mint Picture Scroll") which is reproduced in Nihon Ginkou Chousakyoku ed., Zuroku Nihon no kahei, vol. 3 (Tokyo: Touyou Keizai Shinpousha, 1974), pp. 72-79 with notes on pp. 116-117. This scroll pictures the Sendai Ishinomaki mint in the year 1728 and is the oldest scroll picturing copper coin manufacture in Japan. The text was written by Dr. Luke Shepherd Roberts of the University of California at Santa Barbara (UCSB), with minor adjustments.

-

Arriving to work meant a complete change of clothing into work clothes provided by the proprietors of the mint. Coming and going, this was done between two inspectors seated in front and in back of the worker to prevent theft of coins. Similar methods (including x-ray scans) are used by money producers and gem and precious metal miners throughout the world today.

-

Anciently Chinese coins were cast using clay molds, but from the early 600's the use of the sand mold method became common. Japan used the sand mold method from the very beginning of its minting history in the late 600's. The sand mold uses two frames filled with fine grain wetted sand, and a set of carefully manufactured "seed coins" or "mother coins." The man on the right is laying the mother coins on the sand in the mold. He also lays down rods to create the basic path for the molten metal to flow into the space of each coin. After the mother coins are laid out, the second frame filled with sand is laid on top. The man on the left is walking on the paired frames to make sure that the sand presses tightly to the mother coins, so as to produce a fine image.

-

After the mold of the mother coins is pressed sufficiently, the front and back of the mold are separated. The man on the right is cutting clean paths to each coin for the molten metal. The man in the center is removing the mother coins leaving the negative imprint in the sand. The man on the left is heating the sand filled frames with smoky pine. This dries the sand but the resin smoke helps the sand stick together to maintain its shape. The carbon also helps the molten metal flow more smoothly. Coins fresh from the mold are usually covered in pine resin soot.

-

After the mold is prepared then the two sides are clamped tightly together, as on the right side of this picture. The man on the left is finishing the final stages of preparing the molten metal. This was a mixture of copper with lead, tin, nickel, iron or other metals including toxic metals such as mercury and arsenic. Copper was usually predominant but some coins contain so much nickel or iron that they can be picked up with a magnet. Others contain so much lead that they are chalky and grey. The relative proportions of metal were often subject to availability and market forces.

-

This picture shows the workers on the right pouring the molten metal into the sand mold, which has been stood up on its end. The man in the center is removing the coins from the mold after it has cooled and been opened up. The picture makes it seem as if he is removing them one by one, but this seems unlikely. The copper in the path to the coins has cooled as well and the coins are lifted out by this frame of hardened metal. They look like leaves on a branch. This is called in English a "coin tree" or in Japanese an "edasen." They are then cut or broken off the branch one by one. Some coins will have the traces of where the metal path came into their edge, either a slight lump still sticking out or a bite into the edge of the coin itself where the coin was broken off clumsily.

-

After the coins are broken off the "tree" then they are placed on square rods and filed down so that the edges are smooth as possible. The two men in the center are filing the outside edges of the coins, while the man on the left is filing the inside square hole. This is time consuming and expensive to do, so one mon coins from the late Edo period are frequently not filed as carefully as earlier coins. In terms of care of production the 1660's was probably the apogee of Japanese cash coin manufacture. It is interesting that this coincides with the apogee of Tokugawa and daimyo lord authority as well. From the mid-eighteenth century producers learned how to make more coins faster and more cheaply but all in all the quality declines. The Sendai mint pictured here had excellent quality control and made beautiful coins even in the eighteenth century.

-

Next the coins are reheated in order to strenghten them. This is pictured on the right. Then they are checked by the man on the left to make sure that they are flat. Bent ones are presumably recycled.

-

These men seem to be polishing the surfaces of the coins and doing other checking for quality. Many coins also are made with accidental holes in them due to the metal cooling too quickly, so most of these are caught during manufacture and recycled. Some such coins nevertheless enter circulation.

-

The men on the right are giving the coins all strung on a rod a final rounding polish. The men on the left are stomping on the coins in a large pestle. Why? well the book cited above says "It must be part of the production process." So there. An anthropologist would say "It must be a religious rite."

-

Next the coins are washed to remove filing dust etc. as being done by the man on the right. The water is then screened to retrieve the metal for recycling. This is called Genta nagashi. I have not included the picture here. After being washed the coins are dried to prevent early corrosion.

-

The men on the right are yet again polishing the outside edges of the coin on a bed of straw. The men on the left are tying the coins onto strings of a standard count of say 300 or 500 coins.

-

These men are stacking and counting the strings of coins. The man on the lower left is counting and recording the amounts in an account book set by him on the floor. The man on the top center seems to have unstrung a roll to inspect. Perhaps he is another quality control man.

-

The producer of the coins is a subcontractor to the government. He keeps an agreed-upon portion for his income and to cover production costs and then gives up the remainder to the government which is run by samurai. In this case the government is that of Sendai domain. This picture shows the owner or manager going with a bevy of servants carrying the coins to the government coin office.

-

The coins are then laid upon the "coin stage" at the samurai government office. Most of the commoner workers are beneath the status permitting them to step up on the floor of the office so they wait kneeling below. Two commoner inspectors (kabiya) crouch on stage while behind him a man announces the arrival while beating a drum.

-

In this the last stage, samurai officials inspect and accept the coins. Notice the swords, markers of their status, which they have laid on the floor beside them. The chief officials are at the far left and they inspect a few samples presented them in trays. A white document, probably presenting sum totals, sits on the floor in front of one of these samurai. In the lower right sits two people. One is the Chief Inspector of the domain, the Oometsuke. To his right sits a representative of the domain accounting office, kanjougata, and he is weighing a string of coins to confirm that they meet specifications. Manufacturers like to shrink the size of the coins to save money. The three men at top center, called "myoudai," are some kind of representative but of whom are not identified by the scroll. The two men at the right are two more representatives of the Chief Inspector's office.

Zeniza emaki (Second attempt)[edit]

The description below follows selections from the Zeniza emaki ("Cash Mint Picture Scroll") which is reproduced in Nihon Ginkou Chousakyoku ed., Zuroku Nihon no kahei, vol. 3 (Tokyo: Touyou Keizai Shinpousha, 1974), pp. 72-79 with notes on pp. 116-117. This scroll pictures the Sendai Ishinomaki mint in the year 1728 and is the oldest scroll picturing copper coin manufacture in Japan. The text was written by Dr. Luke Shepherd Roberts of the University of California at Santa Barbara (UCSB), with minor adjustments.

| Description | Illustration |

|---|---|

| Arriving to work meant a complete change of clothing into work clothes provided by the proprietors of the mint. Coming and going, this was done between two inspectors seated in front and in back of the worker to prevent theft of coins. Similar methods (including x-ray scans) are used by money producers and gem and precious metal miners throughout the world today. |

|

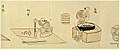

| Anciently Chinese coins were cast using clay moulds, but from the early 600's the use of the sand mould method became common. Japan used the sand mould method from the very beginning of its minting history in the late 600's. The sand mould uses two frames filled with fine grain wetted sand, and a set of carefully manufactured "seed coins" or "mother coins." The man on the right is laying the mother coins on the sand in the mould. He also lays down rods to create the basic path for the molten metal to flow into the space of each coin. After the mother coins are laid out, the second frame filled with sand is laid on top. The man on the left is walking on the paired frames to make sure that the sand presses tightly to the mother coins, so as to produce a fine image. |

|

| After the mould of the mother coins is pressed sufficiently, the front and back of the mould are separated. The man on the right is cutting clean paths to each coin for the molten metal. The man in the centre is removing the mother coins leaving the negative imprint in the sand. The man on the left is heating the sand filled frames with smoky pine. This dries the sand but the resin smoke helps the sand stick together to maintain its shape. The carbon also helps the molten metal flow more smoothly. Coins fresh from the mould are usually covered in pine resin soot. |

|

| After the mould is prepared then the two sides are clamped tightly together, as on the right side of this picture. The man on the left is finishing the final stages of preparing the molten metal. This was a mixture of copper with lead, tin, nickel, iron or other metals including toxic metals such as mercury and arsenic. Copper was usually predominant but some coins contain so much nickel or iron that they can be picked up with a magnet. Others contain so much lead that they are chalky and grey. The relative proportions of metal were often subject to availability and market forces. |

|

| This picture shows the workers on the right pouring the molten metal into the sand mould, which has been stood up on its end. The man in the centre is removing the coins from the mould after it has cooled and been opened up. The picture makes it seem as if he is removing them one by one, but this seems unlikely. The copper in the path to the coins has cooled as well and the coins are lifted out by this frame of hardened metal. They look like leaves on a branch. This is called in English a "coin tree" or in Japanese an "edasen." They are then cut or broken off the branch one by one. Some coins will have the traces of where the metal path came into their edge, either a slight lump still sticking out or a bite into the edge of the coin itself where the coin was broken off clumsily. |

|

| After the coins are broken off the "tree" then they are placed on square rods and filed down so that the edges are smooth as possible. The two men in the centre are filing the outside edges of the coins, while the man on the left is filing the inside square hole. This is time consuming and expensive to do, so one mon coins from the late Edo period are frequently not filed as carefully as earlier coins. In terms of care of production the 1660's was probably the apogee of Japanese cash coin manufacture. It is interesting that this coincides with the apogee of Tokugawa and daimyo lord authority as well. From the mid-eighteenth century producers learned how to make more coins faster and more cheaply but all in all the quality declines. The Sendai mint pictured here had excellent quality control and made beautiful coins even in the eighteenth century. |

|

| Next the coins are reheated in order to strengthen them. This is pictured on the right. Then they are checked by the man on the left to make sure that they are flat. Bent ones are presumably recycled. |

|

| These men seem to be polishing the surfaces of the coins and doing other checking for quality. Many coins also are made with accidental holes in them due to the metal cooling too quickly, so most of these are caught during manufacture and recycled. Some such coins nevertheless enter circulation. |

|

| The men on the right are giving the coins all strung on a rod a final rounding polish. The men on the left are stomping on the coins in a large pestle. Why? well the book cited above says "It must be part of the production process." So there. An anthropologist would say "It must be a religious rite." |

|

| Next the coins are washed to remove filing dust etc. as being done by the man on the right. The water is then screened to retrieve the metal for recycling. This is called Genta nagashi. I have not included the picture here. After being washed the coins are dried to prevent early corrosion. |

|

| The men on the right are yet again polishing the outside edges of the coin on a bed of straw. The men on the left are tying the coins onto strings of a standard count of say 300 or 500 cash coins. |

|

| These men are stacking and counting the strings of coins. The man on the lower left is counting and recording the amounts in an account book set by him on the floor. The man on the top centre seems to have unstrung a roll to inspect. Perhaps he is another quality control man. |

|

| The producer of the coins is a subcontractor to the government. He keeps an agreed-upon portion for his income and to cover production costs and then gives up the remainder to the government which is run by samurai. In this case the government is that of Sendai domain. This picture shows the owner or manager going with a bevy of servants carrying the coins to the government coin office. |

|

| The coins are then laid upon the "coin stage" at the samurai government office. Most of the commoner workers are beneath the status permitting them to step up on the floor of the office so they wait kneeling below. Two commoner inspectors (kabiya) crouch on stage while behind him a man announces the arrival while beating a drum. |

|

| In this the last stage, samurai officials inspect and accept the coins. Notice the swords, markers of their status, which they have laid on the floor beside them. The chief officials are at the far left and they inspect a few samples presented them in trays. A white document, probably presenting sum totals, sits on the floor in front of one of these samurai. In the lower right sits two people. One is the Chief Inspector of the domain, the Oometsuke. To his right sits a representative of the domain accounting office, kanjougata, and he is weighing a string of coins to confirm that they meet specifications. Manufacturers like to shrink the size of the coins to save money. The three men at top centre, called "myoudai," are some kind of representative but of whom are not identified by the scroll. The two men at the right are two more representatives of the Chief Inspector's office. |

|

References[edit]

Zeniza emaki attribution[edit]

Attribution: Dr. Luke Shepherd Roberts, available from http://www.history.ucsb.edu/faculty/roberts/coins/index.html

Korean mun[edit]

Significant hoards[edit]

- User:Donald Trung/History of the manufacturing process of cash coins/Coin hoards.

Done. --Donald Trung (talk) 21:31, 29 April 2020 (UTC) .

Done. --Donald Trung (talk) 21:31, 29 April 2020 (UTC) .

Spin-off projects[edit]

- == Japanese coin hoards == .

- Japanese feudal jug found to contain 260,000 coins - 10/15/2018 10:00:00 PM (The Archaeology News Network).

- [[User:Donald Trung/