User:Lethesl/Berlioz

Louis Hector Berlioz (December 11, 1803 – March 8, 1869) was a French Romantic composer, best known for his compositions Symphonie fantastique and Grande Messe des morts (Requiem). Berlioz made great contributions to the modern orchestra with his Treatise on Instrumentation and by utilizing huge orchestral forces for his works, sometimes calling for over 1000 performers.[citation needed] At the other extreme, he also composed around 50 songs for voice and piano.

Biography[edit]

Early years[edit]

Berlioz was born in France at La Côte-Saint-André[1] in the département of Isère, near Lyon on 11 December, 1803.[2] His father was a respected[3] provincial physician[4] and scholar and was responsible for much of the young Berlioz's education.[3] His father was an atheist,[4] with a liberal outlook,[5] while his mother an orthodox Roman Catholic.[3][4] He had five siblings in all, three of whom did not survive to adulthood.[6] The other two, Nanci and Adèle, remained close to Berlioz throughout their lives.[5] Berlioz did not begin his study in music until the age of twelve, when he began writing small compositions and arrangements. By this age he has also learnt to read Virgil in Latin and translate it into French under his fathers tuition. Unlike many other composers of the time, he was not a child prodigy, and never learned to play the piano,[7], but did learn to play the flute and guitar as a boy.[7][8] He learnt harmony by textbooks alone - he was not formally trained.[8][7] Still at the age of twelve, as recalled in his Mémoires, he experienced his first passion for a woman, an 18 year old next door neighbour named Estelle Fornier (née Dubœuf).[3][9] The majority of his early compositions were romances and chamber pieces.[7][10] Berlioz appears to have been innately Romantic, - this characteristic manifesting itself in his love affairs, adoration of great romantic literature,[11] and his weeping at passages by Virgil,[5] Shakespeare, and Beethoven.

Student life[edit]

Paris[edit]

In 1821 at the age of eighteen, Berlioz was sent to Paris to study medicine,[12][4] a field in which he had no interest, and later, outright disgust towards after viewing a human corpse being dissected,[3][4] which he later detailed in a colourful account in his Mémoires.[13] He began to take advantage of the institutions he now had access to in the city, including his first visit to the Paris Opéra, where he saw Iphigénie en Tauride by Christoph Willibald Gluck, a composer whom he came to admire above all, jointly alongside Ludwig van Beethoven. He also began to visit the Paris Conservatoire library, where he sought out scores of Gluck's operas, and made personal copies of parts of them. His Mémoires recall his first encounter in that library with the Conservatoire's then music director Luigi Cherubini, in which Cherubini attempted to throw out the impetuous Berlioz, who was not a formal music student.[14][15] Berlioz also heard two operas by Gaspare Spontini, a composer who influenced him through their friendship, and who he later championed when working as a critic. From then on, he devoted himself to composition, encouraged by Jean-François Lesueur, director of the Royal Chapel and professor at the Conservatoire. In 1823, he wrote his first article in the form of a letter to the journal Le Corsaire defending Spontini's La Vestale. By now he had composed several works including Estelle et Némorin and Le Passage de la mer Rouge (The Crossing of the Red Sea) - both now lost - the latter of which convinced Lesueur to take Berlioz on as one of his private pupils.[3]

Despite his parents disapproval,[11] in 1824 he formally abandoned his medical studies[4] to pursue a career in music. He composed the Messe solennelle, which was rehearsed, and revised after the rehearsal, but not performed again until the following year. Berlioz later claimed to have burnt the score,[16] but it was miraculously re-discovered in 1991.[17][18] Later that year or in 1825, he began to compose the opera Les francs-juges, which was completed the following year but went unperformed. The work survives only in fragments,[19] but the overture survives and is sometimes played in concert. In 1826 he began attending the Conservatoire[12] to study composition under Lesueur and Anton Reicha. He also submitted a fugue to the Prix de Rome, but was eliminated in the primary round. Winning the prize would become an obsession for him until he finally won it in 1830 - he submitted a new cantata every year until he succeeded at his fourth attempt. The reason for this interest in the prize was not just academic recognition, but because part of the prize included a five year pension[20] - much needed income for the struggling composer. In 1827 he composed the Waverly overture after Walter Scott's[12] Waverley novels. He also began working as a chorus singer at a vaudeville theatre to contribute towards an income.[4][9] Later that year, he saw his future wife Harriet Smithson at the Odéon theatre playing Ophelia and Juliet in Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare. He immediately became infatuated by both actress[11] and playwright.[12] From then on, he began to send Harriet messages, but she considered Berlioz's letters introducing himself to her so overly passionate that she refused his advances.[4]

In 1828 Berlioz heard Beethoven's third and fifth symphonies performed at the Paris Conservatoire - an experience that he found overwhelming.[21] He also read Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Faust for the first time (in French translation), which would become the inspiration for Huit scènes de Faust (his Opus 1), much later re-developed as La damnation de Faust. He also came into contact with Beethoven's string quartets[22] and piano sonatas, and recognised the importance of these immediately. He began to study English so that he could read Shakespeare. At a similar time, he also began to write musical criticism.[4] He began and finished composition of the Symphonie fantastique in 1830, a work which would bring Berlioz much fame and notoriety. He entered into a relationship with - and subsequently became engaged to - Camille Moke, despite the symphony being inspired by Berlioz's obsession with Harriet Smithson. As his fourth cantata for submittal to the Prix de Rome neared completion, the July Revolution broke out. "I was finishing my cantata when the Revolution broke out," he recorded in his Mémoires, "I dashed off the final pages of my orchestral score to the sound of stray bullets coming over the roofs and pattering on the wall outside my window. On the 29th I had finished, and was free to go out and roam about Paris 'till morning, pistol in hand".[23] Shortly later, he finally wins the prize[24][25] with the cantata Sardanapale. He also arranged the French national anthem La Marseillaise as well as composed an overture to Shakespeare's The Tempest, which was the first of his pieces to play at the Paris Opéra, but an hour before the performance began, quite ironically, a sudden storm created the worst rain in Paris for 50 years, meaning the performance was almost deserted.[26] Berlioz met Franz Liszt who was also attending the concert. This proved to be the beginning of a long friendship. Liszt would later transcribe the entire Symphonie fantastique for piano to enable more people to hear it.

Italy[edit]

On the 30 December, Berlioz travelled to Italy, since a clause in the Prix de Rome award required a winner to spend two years in the country. He actually only spent 15 months there between 1831 and 1832, but they were an important inspiration to his music writing even after his return to France, and while he produced none of his very major works while there, the later Harold en Italie (1834) in particular is indebted to his experiences in Italy. While sailing there, he met a group of Carbonari, members of a secret society of Italian patriots based in France with the aim of creating a unified Italy.[27] In Rome he stayed at the French Academy in the Villa Medici, and he travelled out of the city as often as possible. He found the city to his distaste, writing "Rome is the most stupid and prosaic city I know: it is no place for anyone with head or heart".[5] While in Italy he received a letter from the mother of his fiancée informing him that she had called off their engagement and married Camille Pleyel (son of Ignaz Pleyel), a rich piano manufacturer. Berlioz decides to return to Paris to take revenge and kill all three – and conceives an elaborate plan in which to do so. He purchased a dress, hat (with veil) and wig, which he was to use to disguise himself as a woman[28] to gain entry to their building, before killing each of them with a shot of his pistol, saving one shot for himself. He then stole a pair of double-barrelled pistols from the Academy.[28] He also purchased phials of strychnine and laudanum[28] to use as poisons in the event of a pistol jamming. By the time he had reached Genoa by mail coach, he realised that he had left his disguise in the side pocket of a carriage he had later moved from due to a swap at a previous station. By the time he arrived in Nice (at the time part of Italy) he realised that his plan was inappropriate,[28] and he sent a letter to the Academy, requesting that he might be allowed to return. His request was accepted.[9]

While in Nice he composed the overtures to King Lear[6] and Rob Roy,[7] and began work on a sequel to the Symphonie fantastique, Le retour à la vie (The Return to Life),[29] renamed Lélio in 1855. While in Rome, Emile Signol had drawn a portrait of Berlioz, which Berlioz did not consider to be a good likeness of himself. The portrait was finished in its final painted form in April 1832.[30] By the time Berlioz left Italy, he had also visited Pompeii, Naples, Milan, Tivoli, Florence, Turin and Genoa. Italy was important in providing Berlioz with experiences that would be impossible in France, at times, it was as if he was experiencing the Romantic tales of Byron in person, mixing with brigands, corsairs, and peasants.[5] On November 1832 he returned to Paris to promote his music.

Decade of productivity[edit]

The decade between 1830 and 1840 saw Berlioz write many of his most popular and enduring works.[18] The foremost of these are the Symphonie fantastique (1830), Harold en Italie (1834), the Grande Messe des morts (Requiem) (1837) and Roméo et Juliette (1839).

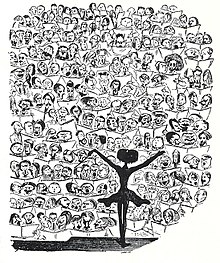

In Paris, Berlioz met playwright Ernest Legouvé who became a lifelong friend. On 9 December a concert including Symphonie fantastique (which had been extensively revised in Italy)[31] and Le retour à la vie was performed, with among others in attendance: Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, Heinrich Heine, Niccolò Paganini, Franz Liszt, Frédéric Chopin, George Sand, Alfred de Vigny, Théophile Gautier, Jules Janin and Harriet Smithson. A few days later, Berlioz and Harriet were introduced, and entered into a relationship. Despite Berlioz not understanding spoken English and Harriet not knowing any French,[9] on 3 October 1833, he and Harriet married at the British Embassy in Paris with Liszt as one of the witnesses,[6] and next year their first child, Louis Berlioz, was born - a source of initial disappointment and anxiety, and eventual pride to his father.[5]

In 1834, virtuoso violinist and composer Paganini commissioned Berlioz to compose a viola concerto,[12] intending to premiere it as soloist. This became the symphony for viola and orchestra, Harold en Italie. However, Paganini changed his mind when he saw the first sketches for the work, saying that he must be playing all the time, and expressing misgivings over its lack of complexity.[citation needed] The premiere of the piece was held later that year, and some time after this performance, Berlioz decided to conduct most of his own concerts from then on. Berlioz composed the opera Benvenuto Cellini in 1836. The piece which followed was one of his most enduring, the Grande Messe des morts, which was first performed at Les Invalides[32] in December of that year.[33] Its gestation was difficult due to the nature of the commission - as it was paid for by the state,[34][25] much bureaucracy had to be endured. There was also opposition from Luigi Cherubini, who was at the time the music director of the Paris Conservatoire. Cherubini felt that a government-sponsored commission should naturally be offered to him rather than the young Berlioz, who was considered an eccentric.[3] (It should be noted, however, that regardless of the animosity between the two composers, Berlioz learned from and admired Cherubini's music,[35] such as the requiem.)[36] Berlioz's mother died on 18 February. Benvenuto Cellini was premiered at the Paris Opéra on 10 September, but was a failure due to a hostile audience.[24][29] After initially rejecting the piece, after hearing Harold en Italie for the first time, Paganini, as Berlioz's Mémoires recount, knelt before Berlioz in front of the orchestra and proclaimed him a genius and heir to Beethoven.[37][34] The next day he sent Berlioz a gift of 20,000 francs,[6][9] the generosity of which left Berlioz uncharacteristically lost for words.[38]

Thanks to money that Paganini had given him, Berlioz was able to pay off Harriet's and his own debts and suspend his work as a critic in order to focus on writing the "dramatic symphony" Roméo et Juliette for voices, chorus and orchestra. Berlioz later identified Roméo et Juliette as his favourite piece among his own musical compositions.[citation needed] (He considered his Requiem his best work, however: "If I were threatened with the destruction of the whole of my works save one, I should crave mercy for the Messe des morts".)[39] It was a success both at home and abroad, unlike later great vocal works such as La damnation de Faust and Les Troyens, which were commercial failures. Roméo et Juliette was premiered in a series of three concerts later in 1839 to distinguished audiences, one including Richard Wagner. The same year, Berlioz was appointed Conservateur adjoint (Deputy Librarian) Paris Conservatoire Library. Berlioz supported himself and his family by writing musical criticism for Paris publications, primarily Journal des Débats for over thirty years, and also Gazette musicale and Le Rénovateur.[7] While his career as a critic and writer[12] provided him with a comfortable income, and he had an obvious talent for writing, he came to detest[18][40][24] the amount of time spent attending performances to review, as it severely limited his free time to promote his own composition[12] and produce more compositions. It should also be noted that despite his prominent position in musical criticism, he did not use his articles to promote his own works.[29]

Mid-life[edit]

After the 1830s, Berlioz found it more difficult to achieve recognition for his music in France, and as a result, he began to travel to other countries with greater frequency. During his lifetime, Berlioz was as famous a conductor as he was as a composer.[41] Between 1842 and 1863 he travelled to Germany, England, Austria, Russia and elsewhere,[7][11] where he conducted operas and orchestral music - both his own and others'.

In 1840, the Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale was commissioned to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the July Revolution of 1830. Due to the strict deadline, it was performed only days after it was completed. The performance was held in the open air on 28 July, conducted by Berlioz himself, at the Place de la Bastille, in honour of the victims of the revolution, and during the performance, the piece was difficult to hear due to the crowds and timpani of the drum corps.[34] Next year he began but later abandoned the composition of a new opera, La Nonne sanglante, of which some fragments survive.[42] This was later remedied by a concert performance a month later, and Wagner voiced his approval of the work.[34] In 1841, Berlioz wrote recitatives for a production of Weber's Der Freischütz at the Paris Opéra, and also orchestrated Weber’s Invitation à la valse to add ballet music to it. Later that year Berlioz finished composing the song cycle Les nuits d'été for piano and voices (later to be orchestrated in a revision). He also entered into a relationship with Marie Recio, a singer, who would become his second wife.

In 1842, Berlioz embarked on a concert tour of Brussels, Belgium from September to October. In December he began a tour in Germany which continued until the middle of next year. Towns visited included: Berlin, Hanover, Leipzig, Stuttgart, Weimar, Hechingen, Darmstadt, Dresden, Brunswick, Hamburg, Frankfurt and Mannheim. On this tour he met Mendelssohn and Schumann (who had written an enthusiastic article on the Symphonie fantastique) in Leipzig, Marschner in Hanover, Wagner in Dresden, Meyerbeer in Berlin.[42] Back in Paris, Berlioz began to compose the concert overture Le Carnaval romain, based on[12] music from Benvenuto Cellini. The work was finished the following year and was premiered shortly after. Nowadays it is among the most popular of his overtures.

In early 1844, Berlioz's highly influential[2][4] Treatise on Instrumentation was published for the first time. At this time Berlioz was producing several serialisations for music journals which would eventually be collected into his Mémoires and Les Soirées de l’Orchestre (Evenings with the Orchestra).[42] He takes a recouperation trip to Nice late that year, during which he composed the concert overture La Tour de Nice (The Tower of Nice), later to be revised and renamed Le Corsaire.[42] Berlioz separated from his wife Harriet, who had long since been suffering from alcohol abuse due to the failure of her acting career,[4] and moved in with Marie Recio. He continued to provide for Harriet for the rest of her life. He also met Mikhail Glinka (who he had initially met in Italy and remained a close friend), who was in Paris between 1844-5, and persuaded Berlioz to embark on one of two tours of Russia. Berlioz's joke "If the Emperor of Russia wants me, then I am up for sale" was taken seriously.[6] The two tours of Russia (the second in 1867) proved so financially successful[6] that they secured Berlioz's finances despite the large amounts of money he was losing in writing unsuccessful compositions. In 1845 he embarked on his first large-scale concert tour of France. He also attended and wrote a report on the inauguration of a statue to Beethoven in Bonn,[42] and began composing La damnation de Faust, incorporating the earlier Huit scènes de Faust. On his return to Paris, the recently completed La damnation de Faust was premiered at the Opéra-Comique, but after two performances, the run was discontinued and the work was a popular failure[43] (perhaps due to its halfway status between opera and cantata), despite receiving generally favourable critical reviews.[44] This left Berlioz heavily in debt[42] to the tune of 5-6000 francs.[44] Becoming ever more disenchanted with his prospects in France, he wrote:

| “ | Great success, great profit, great performances, etc. etc. … France is becoming more and more philistine towards music, and the more I see of foreign lands the less I love my own. Art, in France, is dead; so I must go where it is still to be found. In England apparently there has been a real revolution in the musical consciousness of the nation in the last ten years. We shall see.[5] | ” |

In 1847, during a seven-month visit to England, he was appointed conductor at the London Drury Lane Theatre[42] by its then-musical director, the popular French musician Louis-Antoine Jullien. He was impressed with its quality when he first heard the orchestra perform at a promenade concert.[45] In London he also learnt that he knew far more English than he had supposed, although still did not understand half of what was said in conversation.[45] He began to start writing his Mémoires. During his stay in England, the February Revolution broke out in France. Berlioz arrived back in France in 1848, only to be informed that his father has died shortly after his return. He went back to his birthplace to mourn his father along with his sisters.[42] After his return to Paris, Harriet suffered a series of strokes which left her almost paralysed. Berlioz paid for four servants to look after her on a permanent basis and visited her almost daily.[42] He began composition of his Te Deum.

In 1850 he became Head Librarian at the Paris Conservatoire, the only official post he would ever hold, and a valuable source of income.[42] During this year Berlioz also conducted an experiment on his many vocal critics. He composed a work entitled the Shepherd's Farewell and performed it in two concerts[46] under the guise of it being by a composer named Pierre Ducré. This composer was of course a fictional construct by Berlioz.[47] The trick worked, and the critics praised the work by 'Ducré' and claimed it was an example that Berlioz would do well to follow. "Berlioz could never do that!", he recounts in his Mémoires, was one of the comments.[46] Berlioz later incorporated the piece into La fuite en Egypte from L'enfance du Christ.[48] In 1852, Liszt revived Benvenuto Cellini[29] in what was to become the "Weimar version" of the opera, containing modifications made with the approval of Berlioz.[49] The performances are the first since the disastrous premiere of 1838. Berlioz travelled to London in the following year to stage it at Theatre Royal, Covent Garden but withdrew it after one performance due to the hostile reception.[5] It was during this visit that he witnessed a charity performance involving six thousand five hundred children singing in St Paul's Cathedral.[50] Harriet Smithson died in 1854. L'enfance du Christ was completed later that year and was well-received upon its premiere. Unusually for a late Berlioz work, it appears to have remained popular long after his death.[43] In October, Berlioz married Marie Recio. In a letter written to his son, he said that having lived with her for so long, it was his duty to do so. In early 1855 Le Retour à la vie was revised and renamed Lélio. Shortly afterwards, the Te Deum received its premiere with Berlioz conducting. During a short visit to London, Berlioz had a long conversation with Wagner over dinner. A second edition of Treatise on Instrumentation was also published, with a new chapter detailing aspects of conducting.[42]

Les Troyens[edit]

In 1856 Berlioz visited Weimar where he attended a performance of Liszt conducting Benvenuto Cellini. His time with Liszt also highlighted Berlioz's increasing lack of appreciation for Wagner's music, much to Liszt's annoyance.[51] Berlioz was convinced by Princess Sayn-Wittenstein - with whom he had corresponded for some time - that he should begin to compose Les Troyens,[42], a subject that he had been contemplating for some time. He began composition of this grandest of grand operas, basing the libretto (which he wrote himself) on Books Two and Four of Virgil's Aeneid, which Berlioz had learnt to read as a child with his father. The idea had already been in his mind for five years or so,[5] and despite the long disillusionment, his creative flame seems to have re-emerged for the composition of the opera. It was to be a five act grand opera, on a similar scale to Meyerbeer's and many others that enjoyed regular performance in Paris - well-rooted in the French tradition, and composed with the Paris Opéra in mind. Yet Berlioz’s chances of securing a production in which his work would receive attention at all adequate to its merits were negligible from the start – a fact he must have been aware of.[52][5] Les Troyens was to be a very personal project for him, a homage to his first literary love, whom he had not forgotten since his discoveries of Shakespeare and Goethe.[52] The onset of an intestinal illness which would plague Berlioz for the rest of his life had now become apparent to him.[42] 1858 saw the completion of Les Troyens in its original form. During a visit to Baden-Baden, Edouard Bénazet commissioned a new opera from Berlioz. The opera was never written due to the onset of illness,[42] but two years later Berlioz wrote Béatrice et Bénédict for him instead, which was accepted.[5] In 1860 the Théâtre-Lyrique in Paris agreed to stage Les Troyens, only to reject it next year. It was soon picked up again by the Paris Opéra.[42] Béatrice et Bénédict was completed on 25 February, 1862.

Marie Recio, Berlioz's wife, died unexpectedly of a heart attack on 13 June at the age of 48. Berlioz met a young woman called Amélie[53] at Montmartre Cemetery, and though she was only 24, he comes close to her.[42] The first performances of Béatrice et Bénédict were held at Baden-Baden on 9th and 11 August. The work had had extensive rehearsals for many months, and despite problems Berlioz found in making the musicians play as delicately as he would like, and even discovering that the orchestra pit was too small before the premiere, the work was a success.[54] Berlioz later remarked that his conducting was much improved due to the considerable pain he was in on the day, allowing him to be "emotionally detached" and "less excitable".[54] Béatrice was sung by Madame Charton-Demeur. Both she and her husband were staunch supporters of Berlioz's music, and she was present at Berlioz's deathbed. Les Troyens was dropped by the Paris Opéra with the excuse that it was too expensive to stage; it was replaced by Wagner's Tannhäuser.[9] The work was attacked by his opponents for its length and demands, and with memories of the failure of Benvenuto Cellini at the Opéra were still fresh.[5] It was then accepted by the new director of the recently re-built Théâtre-Lyrique. In 1863 Berlioz published his last signed article for the Journal des Débats.[42] After resigning, an act which should have raised his spirits given how much he detested his job, his disillusionment became even stronger.[5] He also busied himself judging entrants for the Prix de Rome - arguing successfully for the eventual winner, the 21 year old Jules Massenet.[55] Amélie requested that they end their relationship, which Berlioz did, to his despair.[42] The staging of Les Troyens was fraught with difficulties when performed in a truncated form at the Théâtre-Lyrique. It was eventually premiered on 4 November and ran for 21 performances until 20 December. Madame Charton-Demeur sang the role of Didon. It was first performed in Paris without cuts as recently as 2003 at the Théâtre du Châtelet, conducted by John Eliot Gardiner.[56]

Later years[edit]

In 1864 Berlioz was made Officier de la Légion d’honneur. On 22 August, Berlioz heard from a friend that Amélie, who had been suffering from poor health, had died at the age of 26. A week later, while walking in the Montmartre Cemetery, he discovered Amélie’s grave: she had been dead for six months.[42] By now, many of Berlioz's friends and family had died, including both of his sisters. Events like these became all too common in his later life, as his continued isolation from the musical scene increased as the focus shifted to Germany.[8] He wrote:

| “ | I am in my 61st year; past hopes, past illusions, past high thoughts and lofty conceptions. My son is almost always far away from me. I am alone. My contempt for the folly and baseness of mankind, my hatred of its atrocious cruelty, have never been so intense. And I say hourly to Death: ‘When you will’. Why does he delay?[8] | ” |

Berlioz met Estelle Fornier - the object of his childhood affections - in Lyon for the first time in 40 years, and began a regular correspondence with her.[42] Berlioz soon realised that he still longed for her, and eventually she had to inform him that there was no possibility that they could become closer than friends.[57] By 1865, an initial printing of 1200 copies of his Mémoires was completed. A few copies were distributed amongst his friends, but the bulk were, slightly morbidly, stored in his office at the Paris Conservatoire, to be sold upon his death.[5] He travelled to Vienna in December 1866 to conduct the first complete performance there of La damnation de Faust. In 1867 Berlioz's son Louis, a merchant shipping captain, died[7] of yellow fever[4] in Havanna.[9] In his study, Berlioz burnt a large number of documents and other mementos which he had accumulated during his life,[42] keeping only a conducting baton given to him by Mendelssohn and a guitar given to him by Paganini.[9] He then wrote his will. The intestinal pains had been gradually increasing, and had now spread to his stomach, and whole days were passed in agony. At times he experienced spasms in the street so intense that he could barely move.[58] Later that year he embarks on his second concert tour of Russia, which would also be his last of any kind. The tour was extremely lucrative for him, so much so that Berlioz turned down an offer of 100,000 francs from American Steinway to perform in New York.[6] In St. Petersburg, Berlioz experienced a special pleasure at performing with the "first-rate" orchestra of the St. Petersburg Conservatory.[6] He returned to Paris in 1868, exhausted, with his health damaged due to the Russian winter.[9] He immediately travelled to Nice to recuperate in the Mediterranean climate, but slipped on some rocks by the sea shore, possibly due to a stroke, and had to return to Paris, where he lived as an invalid.[9]

On 8 March, 1869,[1] Berlioz died at his Paris[2] home, No.4 rue de Calais, at 30 minutes past midday. He was surrounded by friends at the time. His funeral was held at the recently completed Église de la Trinité[59] on 11 March, and he was buried in Montmartre Cemetery with his two wives, who were exhumed and re-buried next to him. His last words were reputed to be "Enfin, on va jouer ma musique" [60][61][41] (They are finally going to play my music). From any other composer, these would be suspected to be apocryphal, but with Berlioz one cannot be so sure.

Berlioz as a conductor[edit]

Berlioz's work as a conductor was highly influential[41] and brought him fame across Europe.[7][11] He was considered by Charles Hallé, Hans von Bülow and others to be the greatest conductor of his era.[62] Berlioz initially began conducting due to frustrations over the inability of other conductors - more used to performing older and simpler music - to master his advanced and progressive works,[63] with their extended melodies[41] and rhythmic complexity.[34] He began with more enthusiasm than mastery,[63] and was not formally trained,[63] but through perseverance his skills improved. He was also willing to take advice from others, as evidenced by Spontini criticising his early use of large gestures while conducting.[62] One year later, according to Hallé, his movements were much more economical, enabling him to control more nuance in the music.[62] His expert understanding of the way the sound of each instrument interacts with each other (demonstrated in his Treatise on Instrumentation) was attested to by the critic Louis Engel, who mentions how Berlioz once noticed, amidst an orchestral tutti, a minute pitch difference between two clarinets.[62] Engel offers an explanation of Berlioz's ability to detect such things as in part due to the sheer nervous energy he was experiencing during conducting.[62]

Despite this talent, Berlioz never held an employed position of conductor during his lifetime, having to be content with conducting only as a guest. This was almost not the case, as late in 1835, he was approached by the management of a new concert hall in Paris, the Gymnase Musical, as to whether he would be interested in becoming their musical director.[64] To Berlioz this was ideal, as not only would it give him a large annual salary (between 6000 to 12,000 francs),[64] but it would also give him a platform from which to perform his own music, and the music of fellow progressives. He even went as far as signing the contract[64] before fate intervened. The obstacle was one of the many restrictions that the revolutionary government had placed on the running of musical establishments. The decree in question was one which prevented all new concert halls from staging any vocal music,[64] so that they do not compete with the influential Paris Opéra among other organisations. There were passionate arguments and attempts to circumvent this restriction, but they fell on deaf ears, and the Gymnase Musical became a dance hall instead.[64] This left Berlioz dejected, and would prove to have been a crucial cross-roads in his life, forcing him to work long hours as a critic, which severely impaired his free time available for composition.

From then on, he conducted at many different occasions, but mainly during grand tours of various countries where he was paid handsomely for visiting. In particular, towards the end of his life, he made a lot of money by touring Russia twice, the final visit proving extremely lucrative and also being the final conducting tour before his death. This enabled him not only to perform his music to a wider audience, but also to increase his influence across Europe - for example, his orchestration was studied by many Russian composers. Not just fellow hyper-Romantic Tchaikovsky, but also members of The Five are indebted to these techniques, including Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, but even Modest Mussorgsky - often portrayed as uninterested in refined orchestration - revered Berlioz[65] and died with a copy of Berlioz's Treatise on Instrumentation on his bed.[61] Similarly, his conducting technique as described by contemporary sources appears to set the groundwork for the clarity and precision favoured in the French School of conducting right up to the present, exemplified by such figures as Pierre Monteux, Désiré-Emile Inghelbrecht, Charles Münch, André Cluytens, Pierre Boulez and Charles Dutoit.

Legacy[edit]

Although neglected in France for much of the 19th century, the music of Berlioz has often been cited as extremely influential in the development of the symphonic form,[66] instrumentation,[67] and the depiction in music of programmatic ideas, features central to musical Romanticism. He was considered extremely progressive for his day, and he, Wagner, and Liszt are sometimes considered the great trinity of progressive 19th century Romanticism. Richard Pohl, the German critic in Schumann's musical journal, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, called Berlioz "the true pathbreaker".[citation needed] Liszt was an enthusiastic performer and supporter, and Wagner himself, after first expressing great reservations about Berlioz, wrote to Liszt saying: "we, Liszt, Berlioz and Wagner, are three equals, but we must take care not to say so to him." [citation needed] As Wagner here implies, Berlioz himself was indifferent to the idea of what was called the "la musique du passé" (music of the past), and clearly influenced both Liszt and Wagner (and other forward-looking composers) although he increasingly began to dislike many of their works.[citation needed] Wagner's remark also suggests the strong ethnocentrism characteristic of European composers of the time on both sides of the Rhine. Berlioz not only influenced Wagner through his orchestration and breaking of conventional forms, but also in his use of the idée fixe in the Symphonie fantastique which foreshadows the leitmotif.[68][69] Liszt came to see Berlioz not only as a composer to support, but also to learn from, considering Berlioz an ally in his aim for "A renewal of music through its closer union with poetry".[70]

During his centenary in 1903, while receiving attention from all leading musical reference books, he was still not generally accepted as being one of the great composers.[71] Some of his music was still in neglect and his following was smaller than other, mainly German, composers. Even half a century did not change much,[71] and it took until the 1960s for the right questions to be asked about his work, and for it to be viewed in a more balanced and sympathetic light. One of the pivotal events in this fresh ignition of interest in the composer was a performance of Les Troyens by Rafael Kubelík in 1957 at Covent Garden.[72] The music of Berlioz enjoyed a revival during the 1960s and 1970s, due in large part to the efforts of British conductor Sir Colin Davis, who recorded his entire oeuvre, bringing to light a number of Berlioz's lesser-known works. An unusual (but telling) example of the increase of Berlioz's fame in the 60s was an explosion of forged autographs, manuscripts, and letters, evidently created to cater for a much greater interest in the composer.[73] Davis's recording of Les Troyens was the first near-complete recording of that work. The work, which Berlioz never saw staged in its entirety during his life, is now a part of the international repertoire,[56] if still something of a rarity. Les Troyens was the first opera performed at the newly built Opéra Bastille in Paris on March 17, 1990 in a production claimed to be complete, but lacking the ballets.[72]

In 2003, the bicentenary of Berlioz's birth, his achievements and status are much more widely recognised,[74] and his music is viewed as both serious and original, rather than an eccentric novelty.[71] Newspaper articles reported his colourful life with zeal, very many festivals dedicated to the composer were held,[75][76] readings of his books[74] and a French dramatised television biography[77] all helped to create a lot of exposure to the composer's life and music - far more than the previous centenary anniversary. Numerous recording projects were begun or reissued,[78] and broadcasts of his music increased.[75] Prominent Berlioz conductor Colin Davis had already been in the process of recording much of Berlioz's music on the LSO Live label, and has continued this project to this date with a L'enfance du Christ recording issued in 2007. The internet was also a factor in the celebrations, with the comprehensive hberlioz.com site (which has been online since 1997) being an easily available source of information to anyone interested in the composer. The 'Berlioz 2003' celebrations, organised by French academic institutions,[74] also had a promenent website, listing events, publications and gatherings[74] the domain of which has now lapsed. There was also a site maintained by the Association nationale Hector Berlioz.[79] A proposal was made to remove his remains to the Panthéon, and while initially encouraged by French President Jacques Chirac,[80][74] it was postponed by him, claimed to be because it was too shortly after Alexandre Dumas was moved there.[81] He may have also been influenced by a political dispute over Berlioz's worthiness as a republican,[61][67] since Berlioz, who regularly met kings and princes, had severely criticized the 1848 Revolution, speaking of the "odious and stupid republic".[citation needed] There were also objections from supporters of Berlioz, some of whom claimed that Berlioz was an anti-establishment figure and would have no interest in such a ceremony, and that he was happy to be buried next to his two wives in the location he has been in for almost 150 years.[67] Since Chirac retired as President, the future of Berlioz's resting place is still unclear.[81]

Musical influences[edit]

Berlioz had a keen affection for literature, and many of his best compositions are inspired by literary works. For Symphonie fantastique, Berlioz was inspired in part by Thomas de Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. For La damnation de Faust, Berlioz drew on Goethe's Faust; for Harold en Italie, he drew on Byron's Childe Harold; for Benvenuto Cellini, he drew on Cellini's own autobiography. For Roméo et Juliette, Berlioz turned, of course, to Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. For his magnum opus, the monumental opera Les Troyens, Berlioz turned to Virgil's epic poem The Aeneid. In his last opera, the comic opera Béatrice et Bénédict, Berlioz prepared a libretto based loosely on Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing. His composition " Tristia" (for Orchestra and Chorus) drew its inspiration from Shakespeare's Hamlet.

Apart from the many literary influences, Berlioz also championed Beethoven who was at the time unknown in France. The performance of the "Eroica" symphony in Paris seems to have been a turning point for Berlioz's compositions. Next to those of Beethoven, Berlioz showed deep reverence for the works of Gluck, Mozart, Étienne Méhul, Carl Maria von Weber and Gaspare Spontini, as well as respect for those of Rossini, Meyerbeer and Verdi.

Curiously perhaps, the adventures in chromaticism of his prominent contemporaries and associates Frederic Chopin and Richard Wagner seemed to have little effect on Berlioz's style.

Works[edit]

Musical works[edit]

The five movement Symphonie fantastique, partly due to its fame, is considered by most to be Berlioz's most outstanding work,[82] and the work had a considerable impact when new.[2][3] It is famous for its innovations in the form of the programmatic symphony. The story behind this work relates to Berlioz himself and can be considered somewhat autobiographical.[83]

In addition to the Symphonie fantastique, some other orchestral works of Berlioz currently in the standard orchestral repertoire include his "légende dramatique" La damnation de Faust and "symphonie dramatique" Roméo et Juliette (both large-scale works for mixed voices and orchestra), and his concertante symphony (for viola and orchestra) Harold en Italie, several concert overtures also remain enduringly popular, such as Le Corsaire and Le Carnaval romain. Amongst his more vocally-oriented works, the song cycle Les nuits d'été and the oratorio L'Enfance du Christ have retained enduring appeal, as have the quasi-liturgical Te Deum and Grande Messe des morts.

The unconventional music of Berlioz irritated the established concert and opera[5] scene. Berlioz often had to arrange for his own performances as well as pay for them himself. This took a heavy toll on him financially[44] and emotionally. The nature of his large works - sometimes involving hundreds of performers[84] - made financial success difficult. His journalistic abilities became essential for him to make a living and he survived as a witty critic,[12] emphasizing the importance of drama and expressivity in musical entertainment. It was perhaps this expense which prevented Berlioz from composing more opera than he did. His talent in the genre is obvious, but opera is the most expensive of all classical forms, and Berlioz in particular struggled to arrange stagings of his operas. due to conservative Paris opera companies unwilling to perform his work.[24]

Literary works[edit]

While Berlioz is best known as a composer, he was also a prolific writer, and supported himself for many years by writing musical criticism, utilising a bold, vigorous style, at times imperious and sarcastic. He wrote for many journals, including Le Rénovateur,[85] Journal des Débats and Gazette musicale.[86] He was active in the Débats for over thirty years until submitting his last signed article in 1863.[42] Almost from the founding, Berlioz was a key member of the editorial board of the Gazette as well as a contributor, and acted as editor on several occasions[87] while the owner was otherwise engaged. Berlioz took full advantage of his times as editor, allowing himself to increase his articles written on music history rather than current events, evidenced by him publishing seven articles on Gluck in the Gazette between June 1834 and January 1835.[87] An example of the amount of work he produced is indicated in his producing over one-hundred articles[87] for the Gazette between 1833 and 1837. This is a conservative estimate, as not all of his submissions were signed.[87] In 1835 alone, due to one of his many times of financial difficulty, he wrote four articles for the Monde dramatique, twelve for the Gazette, nineteen for the Débats and thirty-seven for the Rénovateur.[88] These were not mere scribbes, but in-depth articles and reviews with little duplication,[88] which took considerable time to write.

Another noteworthy indicator of the importance Berlioz placed on journalistic integrity and even-handedness were the journals which he both did and did not write for. During the middle of the 1830s the Gazette was considered an intellectual journal, strongly supporting the progressive arts and Romanticism in general, and opposing anything which it considers as debasing this.[87] Exemplified in its long-standing criticism of Henri Herz, and his seemingly endless stream of variations on opera themes, but in to its credit, it also positively reviewed his music on occasion.[89] Its writers included Alexandre Dumas, Honoré de Balzac and George Sand.[87] The Gazette wasn't even unanimous in its praise of Berlioz's music, although it always recognised him as an important and serious composer to be respected.[89] An example of another journal of the same time is the Revue musicale, which thrived on personal attacks, many against Berlioz himself from the pen of critic François-Joseph Fétis.[90] At one point, Robert Schumann was motivated to publish a detailed rebuttal of one of Fétis' attacks on Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique[31] in his own Neue Zeitschrift für Musik journal.[90] Fétis would later contribute to the debasement of the reputation of the Gazette when this journal fails and is absorbed by the Gazette, and he finds himself on the editorial board.[90]

The books which Berlioz has become acclaimed for were compiled from his journal articles.[42] Les Soirées de l’Orchestre (Evenings with the Orchestra) (1852), a scathing satire[91] of provincial musical life in 19th century France, and the Treatise on Instrumentation, a pedagogic work, were both serialised originally in the Gazette musicale.[42] Many parts of the Mémoires (1870) were originally published in the Journal des Débats, as well as Le Monde Illustré.[92] The Mémoires paint a magisterial (if biased) portrait of the Romantic era through the eyes of one of its chief protagonists. Evenings with the Orchestra is more overtly fictional than his other two major books, but its basis in reality is its strength,[91] making the stories it recounts all the funnier due to the ring of truth. W. H. Auden praises it, saying "To succeed in [writing these tales], as Berlioz most brilliantly does, requires a combination of qualities which is very rare, the many-faceted curiosity of the dramatist with the aggressively personal vision of the lyric poet."[93] The Treatise established his reputation as a master of orchestration.[7] The work was closely studied by Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss and served as the foundation for a subsequent textbook by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov who as a music student attended the concerts Berlioz conducted in Moscow and St. Petersburg.[61]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Matthew Bruce Tepper's Hector Berlioz Page

- ^ a b c d The Internet Public Library | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ a b c d e f g h Its.Caltech.edu | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Think Quest | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Andante.com - "Everything classical" | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ a b c d e f g h IMDb.com | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j w3.rz-berlin.mpg.de - The Classical Music Pages | Hector Berlioz biography (Grove sourced)

- ^ a b c d EssentialsofMusic.com | Hector Berlioz biography Cite error: The named reference "eom" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Berlioz and Shakespeare - A Romantic Life

- ^ Rhapsody.com | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ a b c d e Karadar.com | Hector Berlioz page

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Naxos Records | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ Berlioz, Hector, translated by Cairns, David (1865, 1912, 2002). The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz. Hardback, pp.20-1. Everyman's Library/Random House. ISBN 0-375-41391-X

- ^ Berlioz, Hector, translated by Cairns, David (1865, 1912, 2002). The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz. Hardback, pp.34-6. Everyman's Library/Random House. ISBN 0-375-41391-X

- ^ HBerlioz.com - Hector Berlioz reference site | Relevent page from the Mémoires (French)

- ^ FindArticles.com | Newish Berlioz from The Musical Times

- ^ HBerlioz.com - Comprehensive Hector Berlioz reference site | The Discovery of Berlioz's Messe Solennelle

- ^ a b c ClassicalArchives.com | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ Cairns, David (1989, rev. 1999). Berlioz: The Making of an Artist, 1803-1832. Paperback, p.144 Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-140-28726-4

- ^ NewAdvent.org - Catholic Encyclopedia | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ Cairns, David (1989, rev. 1999). Berlioz: The Making of an Artist, 1803-1832. Paperback, in general ch.15, directly p.265 Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-140-28726-4

- ^ Cairns, David (1989, rev. 1999). Berlioz: The Making of an Artist, 1803-1832. Paperback, in general ch.15, directly p.311 Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-140-28726-4

- ^ La Marseillaise information site | Hector Berlioz page

- ^ a b c d CarringBush.net | Hector Berlioz page

- ^ a b Encyclopedia.Farlex.com | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ Berlioz, Hector, translated by Cairns, David (1865, 1912, 2002). The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz. Hardback, pp.105-6. Everyman's Library/Random House. ISBN 0-375-41391-X

- ^ Cairns, David (1989, rev. 1999). Berlioz: The Making of an Artist, 1803-1832. Paperback, p.442 Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-140-28726-4

- ^ a b c d Cairns, David (1989, rev. 1999). Berlioz: The Making of an Artist, 1803-1832. Paperback, pp.457-9. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-140-28726-4

- ^ a b c d NNDB.com | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ a b Cairns, David (1989, rev. 1999). Berlioz: The Making of an Artist, 1803-1832. Paperback, p.542 Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-140-28726-4

- ^ a b [[http://members.aol.com/ComposerScott/essays/Berlioz.html Scott D. Farquhar (May 19, 1994) | The Symphonie Fantastique of Hector Berlioz As Viewed by His Contemporaries

- ^ Programme Notes - Berlioz Requiem

- ^ Grande Messe des morts: Historical Background; Features of the Berlioz Style

- ^ a b c d e Encyclopædia Britannica | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ Cairns, David (1989, rev. 1999). Berlioz: The Making of an Artist, 1803-1832. Paperback, p.312+2, pictures, top caption. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-140-28726-4

- ^ Playbill Arts | Interview about Cherubini with Martin Pearlman of Boston Baroque

- ^ HBerlioz.com - Comprehensive Hector Berlioz reference site | Roméo et Juliette page

- ^ Berlioz, Hector, translated by Cairns, David (1865, 1912, 2002). The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz. Hardback, p.243. Everyman's Library/Random House. ISBN 0-375-41391-X

- ^ Royal Albert Hall | Notes to a performance of the Requiem

- ^ FindArticles.com | Music: The tragedy and the glory from The Independent

- ^ a b c d FindArticles.com | Music: The tragedy and the glory from The Independent

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x HBerlioz.com - Comprehensive Hector Berlioz reference site | Chronological list of events in Berlioz's life

- ^ a b Bartleby.com - Great books online | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ a b c Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.361-5 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ a b Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.395 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ a b Berlioz, Hector, translated by Cairns, David (1865, 1912, 2002). The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz. Hardback, p.527. Everyman's Library/Random House. ISBN 0-375-41391-X

- ^ HumanitiesWeb.org | Berlioz biography

- ^ Completely Berlioz | Chronological biography

- ^ Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.494 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ HBerlioz.com | Berlioz in London: St Paul's Cathedral

- ^ Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.587-8 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ a b Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.591 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ Completely Berlioz | Small mention of Amélie

- ^ a b Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.682 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.699 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ a b HBerlioz.com | The première of Les Troyens in November 1963

- ^ Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.660+6 (bottom caption) Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2 Estelle sent Berlioz a photograph of herself, now an old woman, with a written note saying: "...[to] remind you of present realities and to destroy the illusions of the past."

- ^ Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.754 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.779 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ French Government Ministry for Foreign Affairs | Hector Berlioz biography

- ^ a b c d Scena.org - The Lebrecht Weekly | Hector Berlioz: The Unloved Genius

- ^ a b c d e Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.100 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ a b c Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.99 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ a b c d e Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.101 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.761 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ Mascagni.org | The Legacy of the Century

- ^ a b c BBC News | Row mars Berlioz anniversary

- ^ FilmSound.org | Leitmotif revisited

- ^ The Literary Encyclopedia | Leitmotif

- ^ Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.470 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ a b c HBerlioz.com | Berlioz and his Romantic legacy

- ^ a b KBAQ.org | Les Troyens (The Trojans) by Hector Berlioz

- ^ HBerioz.com | Berlios Forgeries

- ^ a b c d e International Herald Tribune | Homage to Berlioz, Not a Century Too Soon Cite error: The named reference "iht" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b HBerlioz.com | A list of 2003 bicentenary celebrations

- ^ International Herald Tribune | Homage to Berlioz, Not a Century Too Soon

- ^ IMDb.com | Moi, Hector Berlioz (2003)

- ^ HBerlioz.com | A Berlioz discography with years of release and reissue

- ^ Berlioz 2003 - Association nationale Hector Berlioz

- ^ HBerlioz.com | Berlioz in Paris: The Panthéon

- ^ a b NPR.org | Berlioz Bicentennial

- ^ HBerlioz.com | Symphonie Fantastique

- ^ NPR.org | Symphonie Fantastique, with Michael Tilson Thomas

- ^ Appendix D: "Berlioz," Broadcast Lecture by Sir Hamilton Harty, 2 March 1936, BBC

- ^ HBerlioz.com | Berlioz Reviews Berlioz, Le Rénovateur, 2-3 novembre 1834

- ^ Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.95 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ a b c d e f Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.96 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ a b Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.85 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ a b Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.97 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ a b c Cairns, David (1999, 2000). Berlioz: Servitude and Greatness (1832-1869). Paperback, p.98 Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028727-2

- ^ a b GreenManReview.com | Evenings with the Orchestra book review

- ^ HBerlioz.com - Comprehensive Berlioz reference site | Original scan of a Mémoires serialisation in Le Monde Illustré

- ^ University of Chigago Press | Evenings with the Orchestra blurb