User:Michael Aurel/Psamathe (Nereid)

To-Do[edit]

- Revise wolf myth versions. Add Hornblower, p. 341 on lines 901–2

- Forbes Irving search

- Secondary source for Nonnus: Verhelst, p. 230 n. 17 to p. 229. Add as source and explain/expand on role with some context.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art 31.11.13

- Phocus death footnote

- Peleus Telamon parentage footnote

- Fix Perseus links

- Euripides - switch to Loeb?

- Add cites to genealogy chart

Sources[edit]

Primary[edit]

Apollodorus[edit]

- 1.2.7

- [7] To Nereus and Doris were born the Nereids,20 whose names are Cymothoe, Spio, Glauconome, Nausithoe, Halie, Erato, Sao, Amphitrite, Eunice, Thetis, Eulimene, Agave, Eudore, Doto, Pherusa, Galatea, Actaea, Pontomedusa, Hippothoe, Lysianassa, Cymo, Eione, Halimede, Plexaure, Eucrante, Proto, Calypso, Panope, Cranto, Neomeris, Hipponoe, Ianira, Polynome, Autonoe, Melite, Dione, Nesaea, Dero, Evagore, Psamathe, Eumolpe, Ione, Dynamene, Ceto, and Limnoria.

- 20 For lists of Nereids, see Hom. Il. 18.38-49; Hes. Th. 240-264ff.; HH Dem. 417-423; Verg. G. 4.334-344; Hyginus, Fab. pp. 28ff., ed. Bunte.

- [7] To Nereus and Doris were born the Nereids,20 whose names are Cymothoe, Spio, Glauconome, Nausithoe, Halie, Erato, Sao, Amphitrite, Eunice, Thetis, Eulimene, Agave, Eudore, Doto, Pherusa, Galatea, Actaea, Pontomedusa, Hippothoe, Lysianassa, Cymo, Eione, Halimede, Plexaure, Eucrante, Proto, Calypso, Panope, Cranto, Neomeris, Hipponoe, Ianira, Polynome, Autonoe, Melite, Dione, Nesaea, Dero, Evagore, Psamathe, Eumolpe, Ione, Dynamene, Ceto, and Limnoria.

- 3.12.6

- Afterwards Aeacus cohabited with Psamathe, daughter of Nereus, who turned herself into a seal to avoid his embraces, and he begot a son Phocus.11

- 11 Compare Hes. Th. 1003ff.; Pind. N. 5.12(21); Scholiast on Eur. Andr. 687, who mentions the transformation of the sea-nymph into a seal. The children of Phocus settled in Phocis and gave their name to the country. See Paus. 2.29.2, Paus. 10.1.1, Paus. 10.30.4. Thus we have an instance of a Greek people, the Phocians, who traced their name and their lineage to an animal ancestress. But it would be rash to infer that the seal was the totem of the Phocians. There is no evidence that they regarded the seal with any superstitious respect, though the people of Phocaea, in Asia Minor, who were Phocians by descent (Paus. 7.3.10), put the figure of a seal on their earliest coins. But this was probably no more than a punning badge, like the rose of Rhodes and the wild celery (σέλινον) of Selinus. See George Macdonald, Coin Types (Glasgow, 1905), pp. 17, 41, 50.

- Afterwards Aeacus cohabited with Psamathe, daughter of Nereus, who turned herself into a seal to avoid his embraces, and he begot a son Phocus.11

Euripides[edit]

- Helen

- 4–15 (pp. 12, 13) [Loeb]

- 4–15 [Perseus]

- Proteus was king of this land when he was alive, [5] living on the island of Pharos and lord of Egypt; and he married one of the daughters of the sea, Psamathe, after she left Aiakos' bed. She bore two children in his palace here: a son Theoklymenos, [because he spent his life in reverence of the gods,] [10] and a noble daughter, her mother's pride, called Eido in her infancy. But when she came to youth, the season of marriage, she was called Theonoe; for she knew whatever the gods design, both present and to come, [15] having received this honor from her grandfather Nereus.

Hesiod[edit]

- Theogony

- 240–262

- [240] And of Nereus and rich-haired Doris, daughter of Ocean the perfect river, were born children, passing lovely amongst goddesses, Ploto, Eucrante, Sao, and Amphitrite, and Eudora, and Thetis, Galene and Glauce, [245] Cymothoe, Speo, Thoe and lovely Halie, and Pasithea, and Erato, and rosy-armed Eunice, and gracious Melite, and Eulimene, and Agaue, Doto, Proto, Pherusa, and Dynamene, and Nisaea, and Actaea, and Protomedea, [250] Doris, Panopea, and comely Galatea, and lovely Hippothoe, and rosy-armed Hipponoe, and Cymodoce who with Cymatolege and Amphitrite easily calms the waves upon the misty sea and the blasts of raging winds, [255] and Cymo, and Eione, and rich-crowned Alimede, and Glauconome, fond of laughter, and Pontoporea, Leagore, Euagore, and Laomedea, and Polynoe, and Autonoe, and Lysianassa, and Euarne, lovely of shape and without blemish of form, [260] and Psamathe of charming figure and divine Menippe, Neso, Eupompe, Themisto, Pronoe, and Nemertes who has the nature of her deathless father.

- 1003–1005

- But of the daughters of Nereus, the Old man of the Sea, Psamathe the fair goddess, [1005] was loved by Aeacus through golden Aphrodite and bore Phocus.

Lycophron[edit]

- 901–902 (pp. 568, 569)

- ... and the lordl of the Wolfm that devoured the atonement and was turned to stone ...

- l Eurypylus from Ormenion in Thessaly (il. ii. 734).

- m When Peleus had collected a herd of cattle as an atonement for the murder of Actor, son of Acastus (schol.) or Eurytion (Ant. Lib. 38) or Phocus (Ovid, M. xi. 381), the herd was devoured by a wolf which Thetis turned into stone. This stone is variously located in Thessaly or Phocis.

- ... and the lordl of the Wolfm that devoured the atonement and was turned to stone ...

Nicander[edit]

- apud Antoninus Liberalis, 38

- WOLF: Nicander tells this tale in the first book of his Metamorphoses. Aeacus, son of Zeus and of Aigina daughter of Asopus, had as sons Telamon and Peleus and a third, Phocus, born of Psamathe, daughter of Nereus. Aeacus was extremely fond of this third son because he was as handsome as he was good. Peleus and Telamon envied him and killed him in secret. For this Aeacus drove them away and they left the isle of Aigina. Telamon settled in the isle of Salamis while Peleus went to Eurytion son of Irus and prayed for and received from him purification from the murder. Later, when hunting, he aimed at a boar and unintentionally killed Eurytion. Again a fugitive, he betook himself to Acastus whose wife's amorous behaviour led to his being marooned alone on Mount Pelion. In his wanderings he encountered Chiron the centaur, sought his help and was received into his cave. Then Peleus brought together many sheep and cattle and led them to Irus as blood money for the slaying of his son. Irus would not accept this price so Peleus led them away and set them free in accordance with the oracle of the god. A wolf, coming upon the animals unattended by herdsmen, ate them all. By divine will this wolf was changed into a rock which stood for a long time between Locris and the land of the Phocians.

Nonnus[edit]

- 43.356–372 (pp. 290–293) [IA] [ToposText]

- Psamathe sorrowful on the beach beside the sea, watching the turmoil of seabattling Dionysos, uttered the dire trouble of her heart in terrified words:

- O Lord Zeus! if thou hast gratitude for Thetis and the ready hands of Briareus, if thou hast [§ 43.362] not forgot Aigaion the protector of thy laws, save us from Bacchos in his madness! Let me never see Glaucos dead and Nereus a slave! Let not Thetis in floods of tears be servant to Lyaios, let me not see her a slave to Bromios, leaving the deep, to look on the Lydian land, lamenting in one agony Achilles, Peleus, Pyrrhos, grandson, husband, and son! Pity the groans of Leucothea, whose husband took their son and slew him — the heartless father butchered his son with the blade of his murderous knife!

- She spoke her prayer, and Zeus on high heard her in heaven.

Ovid[edit]

- Metamorphoses

- 11.348–409 (pp. 144–149) [Loeb] [IA]

- Peleus' herdsman, came running in with breathless haste, crying: "Peleus, Peleus! I come to tell you news of dreadful slaughter." Peleus bade him tell his news, while the Trachinian king himself waited in trembling anxiety. The herdsman went on: "I had driven the weary herd down to the curving shore when the high sun was midway in his course, beholding as much behind him as still lay before. A part of the cattle had kneeled down upon the yellow sands, and lying there were looking out upon the broad, level sea; part was wandering slowly here and there, while others still swam out and stood neck-deep in water. A temple stood near the sea, not resplendent with marble and gold, but made of heavy timbers, and shaded by an ancient grove. The place was sacred to Nereus and the Nereids (these a sailor told me were the gods of that sea, as he dried his nets on the shore). Hard by this temple was a marsh thick-set with willows, which the backwater of the sea made into a marsh. From this a loud, crashing noise filled the whole neighbourhood with fear: a huge beast, a wolf! he came rushing out, smeared with marsh-mud, his great, murderous jaws all bloody and flecked with foam, and his eyes blazing with red fire. He was mad with rage and hunger, but more with rage. For he stayed not to sate his fasting and dire hunger on the slain cattle, but mangled the whole herd, slaughtering all in wanton malice. Some of us, also, while we strove to drive him off, were sore wounded by his deadly fangs and given over to death. The shore, the shallow water, and the swamps, resounding with the bellow- ings of the herd, were red with blood. But delay is fatal, nor is there time to hesitate. While still there's something left, let us all rush on together, and arms, let us take arms, and make a combined attack upon the wolf!" So spoke the rustic. Peleus was not stirred by the story of his loss; but, conscious of his crime, he well knew that the bereaved Nereid1 was sending this calamity upon him as a sacrificial offering to her slain Phocus. The Oetaean king bade his men put on their armour and take their deadly spears in hand, and at the same time was making ready to go with them himself. But his wife, Alcyone, roused by the loud outcries, came rushing out of her chamber, her hair not yet all arranged, and, sending this flying loose, she threw herself upon her husband's neck, and begged him with prayers and tears that he would send aid but not go himself, and so save two lives in one. Then said the son of Aeacus to her : " Your pious fears, O queen, become you ; but have no fear. I am not ungrateful for your proffered help; but I have no desire that arms be taken in my behalf against the strange monster. I must pray to the goddess of the sea." There was a tall tower, a lighthouse on the top of the citadel, a welcome landmark for storm- tossed ships. They climbed up to its top, and thence with cries of pity looked out upon the cattle lying dead upon the shore, and saw the killer revelling with bloody jaw, and with his long shaggy hair stained red with blood. There, stretching out his hands to the shores of the open sea, Peleus prayed to the sea-nymph, Psamathe, that she put away her wrath and come to his help. She, indeed, remained unmoved by the prayers of Peleus; but Thetis, add- ing her prayers for her husband's sake, obtained the nymph's forgiveness. But the wolf, though ordered off from his fierce slaughter, kept on, mad with the sweet draughts of blood; until, just as he was fastening his fangs upon the torn neck of a heifer, the nymph changed him into marble. The body, save for its colour, remained the same in all respects ; but the colour of the stone proclaimed that now he was no longer wolf, that now he no longer need be feared. But still the fates did not suffer the banished Peleus to continue in this land. The wandering exile went on to Magnesia, and there, at the hands of the Haemonian king, Acastus, he gained full absolution from his bloodguiltiness.

- 1 Psamathe, the mother of Phocus whom Peleus had accidentally killed.

- Peleus' herdsman, came running in with breathless haste, crying: "Peleus, Peleus! I come to tell you news of dreadful slaughter." Peleus bade him tell his news, while the Trachinian king himself waited in trembling anxiety. The herdsman went on: "I had driven the weary herd down to the curving shore when the high sun was midway in his course, beholding as much behind him as still lay before. A part of the cattle had kneeled down upon the yellow sands, and lying there were looking out upon the broad, level sea; part was wandering slowly here and there, while others still swam out and stood neck-deep in water. A temple stood near the sea, not resplendent with marble and gold, but made of heavy timbers, and shaded by an ancient grove. The place was sacred to Nereus and the Nereids (these a sailor told me were the gods of that sea, as he dried his nets on the shore). Hard by this temple was a marsh thick-set with willows, which the backwater of the sea made into a marsh. From this a loud, crashing noise filled the whole neighbourhood with fear: a huge beast, a wolf! he came rushing out, smeared with marsh-mud, his great, murderous jaws all bloody and flecked with foam, and his eyes blazing with red fire. He was mad with rage and hunger, but more with rage. For he stayed not to sate his fasting and dire hunger on the slain cattle, but mangled the whole herd, slaughtering all in wanton malice. Some of us, also, while we strove to drive him off, were sore wounded by his deadly fangs and given over to death. The shore, the shallow water, and the swamps, resounding with the bellow- ings of the herd, were red with blood. But delay is fatal, nor is there time to hesitate. While still there's something left, let us all rush on together, and arms, let us take arms, and make a combined attack upon the wolf!" So spoke the rustic. Peleus was not stirred by the story of his loss; but, conscious of his crime, he well knew that the bereaved Nereid1 was sending this calamity upon him as a sacrificial offering to her slain Phocus. The Oetaean king bade his men put on their armour and take their deadly spears in hand, and at the same time was making ready to go with them himself. But his wife, Alcyone, roused by the loud outcries, came rushing out of her chamber, her hair not yet all arranged, and, sending this flying loose, she threw herself upon her husband's neck, and begged him with prayers and tears that he would send aid but not go himself, and so save two lives in one. Then said the son of Aeacus to her : " Your pious fears, O queen, become you ; but have no fear. I am not ungrateful for your proffered help; but I have no desire that arms be taken in my behalf against the strange monster. I must pray to the goddess of the sea." There was a tall tower, a lighthouse on the top of the citadel, a welcome landmark for storm- tossed ships. They climbed up to its top, and thence with cries of pity looked out upon the cattle lying dead upon the shore, and saw the killer revelling with bloody jaw, and with his long shaggy hair stained red with blood. There, stretching out his hands to the shores of the open sea, Peleus prayed to the sea-nymph, Psamathe, that she put away her wrath and come to his help. She, indeed, remained unmoved by the prayers of Peleus; but Thetis, add- ing her prayers for her husband's sake, obtained the nymph's forgiveness. But the wolf, though ordered off from his fierce slaughter, kept on, mad with the sweet draughts of blood; until, just as he was fastening his fangs upon the torn neck of a heifer, the nymph changed him into marble. The body, save for its colour, remained the same in all respects ; but the colour of the stone proclaimed that now he was no longer wolf, that now he no longer need be feared. But still the fates did not suffer the banished Peleus to continue in this land. The wandering exile went on to Magnesia, and there, at the hands of the Haemonian king, Acastus, he gained full absolution from his bloodguiltiness.

- 11.348–409 [Perseus]

Pausanias[edit]

- 2.29.9

- ... Phocus was not, being, if indeed the report of the Greeks be true, the son of a sister of Thetis.

Pindar[edit]

- Nemean

- 5.12 (pp. 50, 51) [Loeb]

- 5.12 [Perseus]

- Phocus was the son of the goddess Psamatheia; he was born by the shore of the sea.

Plutarch[edit]

- Moralia

- 311 E (pp. 292, 293) [Loeb] 311 E (pp. 292, 293) [IA] Parallela minora 25 [Perseus]

- 25. Telamon led out to hunt Phocus, the beloved son of Aeacus by his wife Psamathe. When a boar appeared, Telamon threw his spear at his hated brother and killed him. But his father drove him into exile.b So Dorotheus in the first book of his Metamorphoses.

- b Cf. Frazer on Apollodorus, iii. 12. 6 (L.C.L. vol. ii. p. 57).

- 25. Telamon led out to hunt Phocus, the beloved son of Aeacus by his wife Psamathe. When a boar appeared, Telamon threw his spear at his hated brother and killed him. But his father drove him into exile.b So Dorotheus in the first book of his Metamorphoses.

- [= FGrHist 145 F6]

- [= 289 F4]

- Telamon led out to a hunt Phokos, who was the son of Aiakos by Psamathe and much beloved. When a boar appeared, Telamon threw his spear against the hated one and killed him. But his father drove him into exile, as Dorotheos says in the first book of his Metamorphoses.

Scholia on Euripides' Andromache[edit]

- 687 (Dindorf, pp. 178–179) {[= Alcmeonis, fr. 1 West, pp. 58, 59]}

- Frazer, p. 57 n. 11

- Compare Hes. Th. 1003ff.; Pind. N. 5.12(21); Scholiast on Eur. Andr. 687, who mentions the transformation of the sea-nymph into a seal.

- BNJ 289 F4 (Commentary)

- However, according to a tradition preserved by Pseudo-Apollodoros, Library 3.12.6, and by the scholiast to Euripides, Andromache 687, Phokos’ mother, the Nereid Psamathe, had transformed herself into a seal in attempting to escape the advances of Aiakos.

Tzetzes on Lycophron[edit]

- Gantz, p. 227

- Related in some way to these events is perhaps Lykophron 901–2, which speaks of a wolf turned to stone for devouring a compensation. As the scholia explain the line, this compensation consists of cattle and sheep gathered by Peleus as payment for his accidental killing of Aktor, son of Akastos, while hunting; when the wolf attacks them, Thetis lithifies it. The scholiast also knows, however, of a version in which Psamathe sends the wolf to attack Peleus' herds after he and Telamon have killed Phokos, with the same result.

Secondary[edit]

BNJ[edit]

- commentary on 289 F4

- Jacoby, FGrH 3A, 392 stresses the oddity of the absence of a metamorphosis in a story culled from a book titled Metamorphoses. As he points out, the notion that in an ampler version of the Parallela minora / in Dorotheos Phokos transformed himself in a seal, is a solution of despair; nor can a metamorphosis such as the one that occurs at the end of the version of Antoninus Liberalis 38 (the wolf who eats the cattle, and is then changed into stone) solve the problem. However, according to a tradition preserved by Pseudo-Apollodoros, Library 3.12.6, and by the scholiast to Euripides, Andromache 687, Phokos’ mother, the Nereid Psamathe, had transformed herself into a seal in attempting to escape the advances of Aiakos. While this cannot have figured in the story as narrated in Parallela minora, it is clear that transformations are part of the story’s overall landscape; in this sense, to give as source-reference a book on metamorphosis may have been an intended, allusive joke of Pseudo-Plutarch.

Brill's New Pauly[edit]

- s.v. Aeacus

- By his wife Endeis, A. fathered Peleus and Telamon; many stories give him a further third son with the name Phocus (seal), whose mother was the Nereid Psamathe. Phocus lost his life through his half-brothers, deliberately so, according to most versions; A. thereupon banished them.

- s.v. Phocus (1)

- [1] Mythical hero of Aegina

- Mythical hero of Aegina, son of Aeacus and the Nereid Psamathe; the latter had attempted in vain to stop Aeacus from raping her by turning herself into a seal (phṓkē): hence the name P. for the child of this union (Hes. Theog. 1004f., Apollod. 3,158 and 160; Pind. Nem. 5,12). In Phocis P. marries the princess Asterodia and gives his name to this region (Apollod. 1,86). P. is ultimately killed by his step-brothers Peleus and Telamon, and he is buried in Aegina (Paus. 2,29,9f.). His mother avenges his death (Ov. Met. 11, 346-409; Antoninus Liberalis 38).

- s.v. Psamathe (1)

- (Ψαμάθη/Psamáthē, Ψαμάθα/Psamátha, Ψαμάθεια/Psamátheia).

- [1] Nereid

- Nereid (Hes. Theog. 260; Apollod. 1,12). The mother of Phocus [1] by Aeacus (Hes. Theog. 1004 f.; Pind. Nem. 5,13). Like her sister Thetis, who resisted marriage to Peleus, P. escaped marriage with Aeacus by transforming into a seal (Apollod. 3,158). According to Eur. Hel. 6-14, she later became the wife of Proteus and the mother of Theoclymenus and Theonoë by him. Because Peleus killed her son Phocus, she sent a rapacious wolf against his herds. At the request of Thetis, P. turned the monster to stone, or it was turned to stone by Thetis herself (Ov. Met. 11,346-406; schol. Lycoph. 175; cf. Antoninus Liberalis 38).

Caldwell[edit]

- p. 44 on lines 243–264

- Nereids of individual significance are Amphitrite (243), Thetis (244), Galateia (250), and Psamathe (26).

- p. 45 on line 260

- 260 Psamathe will marry Aiakos and bear a son Phokos (1003-1005). Psamathe changes into a seal in her effort to resist the advances of Aiakos (Ap 3.12.6); hence the name of her son Phokos (from phoke, "seal").

- p. 82 on lines 1003–1005

- 1003-1005 The Nereid Psamathe (260) has an affair with Aiakos, king of the island Aigina and husband of Endeis. Their son Phokos (see on 260) is killed by his better-known Telamon (an ally and lover of Herakles) and Peleus, the future father of Achilleus (Ap 3.12.6, 2.6.4).

Fontenrose[edit]

- pp. 106–107

- Argive Psamathe, Kropotos' daughter, appears to be originally the same as the sea nymph Psamathe, Nereus' daughter. This Nereid was wife of Aiakos, who won his bride in the same way as his son Peleus won Thetis. She turned herself into a seal (phoke) while Aiakos struggled with her, and in due time bore him a son, Phokos. After Phokos was killed by his half brothers Peleus and Telamon, she sent a monstrous wolf against the herds of Peleus. He propitiated her, Thetis supported his prayer, and the wolf was turned to stone.26

- Psamathe's transformation into a seal, her son's name Phokos, and her character as Nereid suggest that she was a woman with a fish body, a mermaid, i.e., a creature something like Keto or Skylla. Another of her husbands was Proteus old man of the sea.27

- The specific introduction of the seal into the story seems to be due to a desire to make her son the eponym of the land Phokis, which folk etymology interpreted as seal-land. In fact, three manuscripts of Apollodorus say that she changed herself into a phykes (wrasse). And her son's name, which appears to be the masculine form of phoke, is identical with a variant of phokaina, the name of a kind of dolphin. True enough, dolphins are as much mammals as seals are, but the Greeks didn't know it: they had no doubt that dolphins and porpoises were fish.28

- This fish-woman, then, lost her son and in wrath attacked cattle through a wolf surrogate. She attacked men too: as Ovid tells the story, men of Peleus' band were killed as they tried to protect the herds from the wolf. The wolf was a monstrous beast (belua vasta); his maw and shaggy coat were smeared with blood; his eyes flashed fire. He ate some of the cattle that he killed; others he wantonly destroyed. These Psamathe meant to be offerings (inferiae) to the dead Phokos, as Poine's victims were offerings only to Psamathe herself but to her son Linos. Furthermore the Nereid Psamathe was temporarily wife of Aiakos, as Argive Psamathe was Apollo's mistress. Peleus' decision to propitiate the Nereid with prayers and offerings rather than to fight her recalls Apollo's instructions to make offerings to Sybaris and to Poine. It is significant too that Psamathe's wolf raided a hero's herds of cattle, a hero, moreover, whose son fought Kyknos. It is also significant that Peleus was then guest in the house of Keyx in Trachis. There is an interesting coincidence of name between Alkyone, Keyx's wife, who enters into Ovid's narrative, and Alkyoneus, intended victim in the Sybaris story.29

- 26 Ovid Met. 11.346–406; Apollod. 3.12.6; Nic. ap. Ant. Lib. 38; Paus. 29.9; Schol. Vet. on Eur. Andr. 687. The identity of the two Psamathes is recognised by Gruppe (1906) 90, 98, who does not, however, present the case for it.

- 27 Eur. Hel 6 f.

- 28 On phykes see D. Thompson (1947) 276–278, Douglas 91928a) 149. There is also a fish that the Greeks called psamathis; Thompson 294. On phokaina, defind porpoise in lexica, ibid. 281. On the Greeks' classification of dolphins see Douglas 158.

- 29 See Ovid Met. 11.363–396.

Gantz[edit]

- p. 220

- ... and at the end of the Theogony, he [Aiakos] is wedded to the Nereid Psamathe and sires a child, Phokos (Th 1003–1005). ... We have seen that in the Theogony Aiakos already has one son, Phokos. But although he is firmly established in the Iliad as the father of Peleus (Il 21.189), and Peleus appears immediately after him in the Theogony (Th 1006&ndash7), the Theogony does not call Peleus the child of Aiakos and Psamathe; probably then the author of this section agreed with the later view that Peleus was born of the union of Aiakos and some other woman. Pindar and Bakchylides call her Endeis (Nem 5.11–12; Bak 13.96–99); Apollodorus (ApB 3.12.6), Plutarch (Thes 10), and Pausanias (2.29.9) concur and assign as her father the Skiron of Megara whom Theseus slew, while for Hyginus (on an emendation: Fab 14.8) and several scholiasts (Σ Nem 5.12; ΣA Il 16.14) this father is Cheiron (Plutarch says that her mother was Chariklo, adding a further note of confusion between Skiron and Cheiron). None of the above sources offers any explanation for the two marriages (or at least matings), although Euripides does claim that Psamathe left the bed of Aiakos (no reason given) and subsequently married Proteus (Hel 4–7). That she originally resisted Aiakos' advaces, turning herself into a seal to try to escape him, is a story related by Apollodorus (ApB 3.12.6) and the scholia to Euripides' Andromache (Σ And 687). With a son named Phokos this metamorphosis is scarcely surprising, but it is hard to say which came first.

- p. 227

- Related in some way to these events is perhaps Lykophron 901–2, which speaks of a wolf turned to stone for devouring a compensation. As the scholia explain the line, this compensation consists of cattle and sheep gathered by Peleus as payment for his accidental killing of Aktor, son of Akastos, while hunting; when the wolf attacks them, Thetis lithifies it. The scholiast also knows, however, of a version in which Psamathe sends the wolf to attack Peleus' herds after he and Telamon have killed Phokos, with the same result.

Grimal[edit]

- s.v. Aeacus, pp. 14–15

- Later, Aeacus coupled with Psamathe, the daughter of Nereus, and fathered a son. Psamathe who like most sea and river divinities possessed the gift of changing her shape, had turned herself into a seal to escape from Aeacus' pursuit, but this was to no avail and the son conceived by this union was given the name of Phocus which recalled his mother's metamorphosis.

- s.v. Psamathe (1), p. 396

- 1. A Nereid who had a son, by Aeacus, named Phocus (Table 30). She had taken on diverse shapes, notably that of a seal, to escape the advances of Aeacus, but nothing prevented him from achieving his aim. When Phocus was killed by his half-brothers Telamon and PELEUS, Psamathe sent a monstrous wolf against the latter's flocks. Later, Psamathe abandoned Aeacus and married PROTEUS, the king of Egypt.

- References, s.v. Psamathe (1), p. 507

- Psamathe (1) Hesiod, Theog. 260; 1004; Apollod. Bibl. 1,2,7; 3,12,6; Pind. Nem. 5,13 (24) and schol.; Antoninus Liberalis, Met. 38; Tzetzes on Lyc. Alex. 53; 175; schol. on Euripides, Andr. 687; Ovid, Met. ii,366ff.; Euripides, Helen 6ff.

Hard[edit]

- p. 52

- Mention should also be made of a lesser Nereid, Psamathe, who was caught by surprise by Aiakos, king of Aegina, and bore him a son Phokos (see p. 531).

- p. 531

- Peleus and Telamon are exiled from Aegina for killing their half-brother Phokos

- For all his high principles, Aiakos mismanaged his family affairs and became estranged from his sons. He married Endeis, daughter of Cheiron (or Skeiron), who bore him his two legitimate children, PELEUS and TELAMON; but he also fathered a son out of wedlock by the Nereid Psamathe.91 On finding herself accosted by a mortal, the sea-nymph tried to escape his embrace by turning herself into a seal (phoke), but he kept a firm hold on her and caused her to conceive a son, PHOKOS, whom he reared as a member of his family.92 He was especially fond of Phokos and showed him such favour that his wife and legitimate sons grew increasingly resentful, until Peleus and Telamon eventually banded together to murder the intruder with the encouragement of their mother. Although accounts differ on whether Peleus or Telamon delivered the fatal blow or both did so jointly, it was generally agreed that they conspired together to cause his death. According to the usual tradition, one or the other killed Phokos by hurling a discus at his head while the three of them were exercising together. Other versions of the legend in which they were said to have killed him because they were jealous of his athletic prowess or simply by accident were plainly of secondary origin. Whatever the exact course of events, Aiakos sent Peleus and Telamon into exile on hearing of the death of Phokos, and never allowed them to set foot on Aegina again.93

- 91 Apollod. 3.12.6, Paus. 2.29.7, cf. Bacch 13.96–9 (two sons by Endeis), Pi. Nem. 5.8–13; Phokos as son by Psamathe, already Hes. Theog. 1003–5.

- 92 Apollod. 3.12.6, schol. Eur. Androm. 687.

- 93 Apollod. 3.12.6 (Telamon kills Phokos), Alcmaeonis fr. 1 Davies (Telamon strikes with discus, Peleus kills with axe), Paus. 2.29.7 (Peleus kills), D.S. 4.72.6 (Peleus kills accidentally).

Kerenyi[edit]

- pp. 64–65

- The following, then, were the daughters of Nereus:157 ... Psamathe, "the sand-goddess"; ...

Larson[edit]

- p. 71

- A doublet of the myth is the conquest by Aiakos, Peleus’ father, of another Nereid. Psamathe, whose name means “sea sand,” turned herself into a seal while trying to escape Aiakos; their son was called Phokos, “seal.”38

Mair[edit]

- pp. 312–313 n. a

- a Peleus and Telamon, sons of Aeacus and Endeis, slew their half-brother Phocus, son of Aeacus and Psamathe. The reluctance of Callimachus to speak of the deed seem to be an echo of Pindar's treatment of the same theme in Nem. V. 14 ff. [Greek]

- pp. 568–569 n. m

- m When Peleus had collected a herd of cattle as an atonement for the murder of Actor, son of Acastus (schol.) or Eurytion (Ant. Lib. 38) or Phocus (Ovid, M. xi. 381), the herd was devoured by a wolf which Thetis turned into stone. This stone is variously located in Thessaly or Phocis.

March[edit]

- s.v. Aeacus, p. 21

- Aeacus was also had by the Nereid Psamathe a son, PHOCUS (1), so named because his mother had changed herself into a seal (phoke) in trying to avoid intercourse with Aeacus.

- s.v. Eidothea, pp. 142–143

- In Euripides' Helen, Eidothea's name is changed to Theonoe: Proteus is here king of Egypt and has had by the Nereid PSAMATHE (1) two children, Theonoe (once called Eido) and a son, Theoclymenus.

- s.v. Phocus (1), pp. 318–319

- Bastard son of AEACUS, king of Aegina, by the Nereid Psamathe. He was given his name from phoke, 'seal', because his mother, being a sea-nymph with the gift of metamorphosis, changed herself into a seal in trying to escape intercourse with his father.

- There are varying traditions about his death. He was killed by one or both of his half-brothers PELEUS and TELAMON, either accidentally, or because they were jealous of his athletic prowess, or because he was hated by their mother Endeis, Aeacus' legitimate wife. Peleus and Telamon were sent into exile by their father, and Psamathe in anger sent a huge wolf to ravages Peleus' herds of cattle. Finally, however, her sister Thetis interceded on Peleus' behalf and the wolf was turned to stone.

- s.v. Psamathe (1), p. 340

- A Nereid (see NEREIDS), daughter of the sea-god NEREUS and the Oceanid Doris. To AEACUS she bore a son, PHOCUS (1), so named because she had changed herself into a seal (phoke) in trying to avoid intercourse with his father. Phocus was brought up in Aeacus' household, but was later killed by his half-brothers, PELEUS and TELAMON. Psamathe, in her anger, sent a huge wolf to ravage Peleus' herds of cattle, but her sister THETIS interceded on Peleus' behalf and the wolf was turned to stone.

- Psamathe married PROTEUS, king of Egypt, and bore him a son, Theoclymenus, and a daughter, Theonoe, (see EIDOTHEA).

- [Hesiod, Theogony 260, 1004–5; Pindar, Nemean 5.11–13; Euripides, Helen 4–15; Apollodorus 1.2.7, 3.12.6; Ovid, Metamorphoses 11.346–406.]

Oxford Classical Dictionary[edit]

- s.v. Phocus, p. 826

- Phocus (Φῶκος), in mythology, son of Aeacus (q.v.) by the nymph Psamathe, who took the shape of a seal, φώκη; hence the name of her son (Apollod. 3. 158). He proved a distinguished athlete, thus arousing the jealousy of the legitimate sons, Peleus and Telamon (qq.v.); they drew lots to see which should kill him, and Telamon, to whom the task fell, murdered him while they were exercising; Aeacus found out and banished them both (ibid. 160).

Paschalis[edit]

- pp. 163–4

- Now there is an episode in the Metamorphoses that narrativizes precisely a situation in which people take up “arms” (arma) in order to defend a “herd of cattle” (armenta). It is the narrative of Peleus and the wolf (11.266–289, 346–409) and runs as follows. Peleus was banished from Aegina for murdering his brother Phocus and found refuge with Ceyx, the peace-loving king of Trachis. He left his flock of sheep (276 greges pecorum), which are not mentioned again, and herd of cattle (armenta) outside the city, asked the king for shelter but concealed his crime. At some point Peleus’ herdsman (348 armenti custos) named Onetor announced that a monstrous wolf was mangling the herd (371–372 sed omne / uulnerat armentum sternitque hostiliter omne). In this report the words uulnerat (“wounds”) and hostiliter (“in a hostile fashion”) form a semantic cluster with armentum thus evoking its etymology from arma. The reader does not need to wait long before the etymology suggested by this semantic cluster is confirmed. The herdsman asks for an immediate call to arms in order to defend the cattle before all is lost (377–378):

- ‘[…] Dum superest aliquid, cuncti coeamus et arma, arma capessamus coniunctaque tela feramus.’

- “[…] While still there’s something left, let us all rush on together, and arms, let us take arms, and make a combined attack upon the wolf!”

- At this point Ceyx orders that his men be armed for the fight (382 induere arma uiros uiolentaque sumere arma; note the anaphora of arma) but Peleus knew that it was the Nereid Psamathe, his murdered brother’s wife, who had sent the bloodthirsty wolf. So he objected to the idea of an armed mobilization against the wolf on his behalf (391 non placet arma mihi contra noua monstra moueri) and from the top of the citadel he prayed to Psamathe that she put an end to her wrath; she remained unmoved but the mediation of Thetis, Peleus’ wife, proved successful and the wolf, still mangling the herd, was eventually changed into marble by Psamathe. The narrative of Peleus and the wolf suggests that the motive of Psamathe’s wrath against Peleus may have been amor towards her murdered husband Phocus; but this element is suppressed and the narrative is organized around arma and armenta. The hypothesis of amor with reference to a wife’s devotion to her dead husband should be considered also in light of Alcyone’s love for Ceyx (11.384–388), their separation and the bond of conjugal love that survives death and is immortalized by Ovid in the next episode (Met. 11.410–748).

- Based on existing evidence, the idea to organize the narrative of Peleus and the wolf around armenta and arma is probably Ovid’s own. Chapter 38.5 of Antoninus Liberalis’ Metamorphoses offers a very brief treatment of the wolf story, derived from Nicander’s Heteroioumena, but the only things it has in common with Ovid’s version is that a wolf attacked Peleus’ sheep (not cattle) that were unattended by herdsmen, ate them all and was next turned to stone by divine will.32

- 32 “A wolf, coming upon the sheep unattended by herdsmen, ate them all. By divine will this wolf was changed onto a rock which stood for a long time between Locris and the land of the Phocians” (translated by Celoria 1992).

- Now there is an episode in the Metamorphoses that narrativizes precisely a situation in which people take up “arms” (arma) in order to defend a “herd of cattle” (armenta). It is the narrative of Peleus and the wolf (11.266–289, 346–409) and runs as follows. Peleus was banished from Aegina for murdering his brother Phocus and found refuge with Ceyx, the peace-loving king of Trachis. He left his flock of sheep (276 greges pecorum), which are not mentioned again, and herd of cattle (armenta) outside the city, asked the king for shelter but concealed his crime. At some point Peleus’ herdsman (348 armenti custos) named Onetor announced that a monstrous wolf was mangling the herd (371–372 sed omne / uulnerat armentum sternitque hostiliter omne). In this report the words uulnerat (“wounds”) and hostiliter (“in a hostile fashion”) form a semantic cluster with armentum thus evoking its etymology from arma. The reader does not need to wait long before the etymology suggested by this semantic cluster is confirmed. The herdsman asks for an immediate call to arms in order to defend the cattle before all is lost (377–378):

Peck[edit]

- s.v. Phocus

- 1. The son of Aeacus and the nymph Psamathé, slain by his half-brothers Telamon and Peleus, who were therefore sent into banishment by Aeacus. From him the country Phocis derived its name (Pausan. ii. 29, 2).

- s.v. Proteus

- His Egyptian name is said to have been Cetes, for which the Greeks substituted that of Proteus. His wife is called Psamathé or Toroné, and, besides the above-mentioned sons, Theoclymenus and Theonoë are likewise called his children.

Smith[edit]

- s.v. Ae'acus

- By Endeis Aeacus had two sons, Telamon and Peleus, and by Psamathe a son, Phocus, whom he preferred to the two others, who contrived to kill Phocus during a contest, and then fled from their native island.

- s.v. Peleus

- He was a brother of Telamon, and step-brother of Phocus, the son of Aeacus, by the Nereid Psamathe. (Comp. Hom. Il. 16.15, 21.189; Ov. Met. 7.477, 12.365; Apollon. 2.869, 4.853 ; Orph. Argon. 130.)

- s.v. Phocus (2)

- 2. A son of Aeacus by the Nereid Psamathe, and husband of Asteria or Asterodia, by whom he became the father of Panopeus and Crissus. (Hes. Theoy. 1094; Pind. N. 5.23; Tzetz. ad Lyc. 53, 939; Schol. ad Eurip. Or. 33.) As Phocus surpassed his step-brothers Telamnn and Peleus in warlike games and exercises, they being stirred up by their mother Endeis, resolved to destroy him, and Telamon, or, according to others, Peleus killed him with a disculs (some say with a spear during the chase). The brothers carefully concealed the deed, but it was nevertheless found out, and they were obliged to enmigrate from Aegina. (Apollod. 3.12.6; Paus. 2.29.7; Plut. Parall. Min. 25.) Psamathe afterwards took vengeance for the murder of her son, by sending a wolf among the flocks of Peleus, but she was prevailed upon by Thetis to change the animal into a stone. (Tzetz. ad Lyc. 901; Ant. Lib. 38.)

- s.v. Proteus

- His wife is called Psamathe (Eur. Hel. 7) or Torone (Tzetz. ad Lyc. 115), and, besides the above mentioned sons, Theoclymenus and Theonoe are likewise called his children. (Eur. Hel. 9, 13.)

Szabados[edit]

- p. 568

- Translation:

- (Ψαμάθη) Néréide (>Nereides) whose name appears in Hes. theog. 260, Apollod. bibl. 1 (12) 2, 7. and Nonn. Dion. 43, 360. D'Aaque (>Aiakos), from which she tries to escape by metamorphosing into a seal (Apollod. bibl. 3 [158] 12, 6), she has a son, >Phokos (III) (Hes. theog. 1004–1005; Pind., N. 5, 12–13), then she becomes the wife of >Proteus to whom she gives a son, Théoclyméne, and a daughter, Théonoé (or Eidö, Eur. Hel. 6-15). She sends against the herds of >Peleus, who had killed Phokos, a wolf that she, or Thetis, petrifies at the request of the latter (Ov. Met. 11, 365–406; Ant. Lib. 38; Tzetz. Lykophr. 175).

- BIBLIOGRAPHY: Gallina, A., EAA VI (1965) 531 sb "Psamathe"; Herzog-Hauser, G., RE XVII (1936) 20 no. 73 > D "Nereiden"; Höfer, O., ML III 2 (1902-09) 3194-3196 s. v. "Psamathe r"; Radke, G., RE XXIII 2 (1959) 1297-1298 s.v. "Psamathe 1"; idem, KlPauly IV (1972) 1209 s. v "Psamathe".

- CATALOGUE

- Attic vases with f.r.

- 1 (= Kymathoe 1 with bibl. and cross-references, = Peleus 171, = Speio 1) Dinos. Würzburg, Univ. L 540, = ARV 992, 69: P. of Achilles. - About 450 BC. - Struggle of Thetis and Peleus: Nereus and seven Nereids, including P., current (inscribed names).

- 2.* (= Nereides 328 with bibl. and references) Fr. Vienna, Univ. 505. De Vulci, - ARV 1030, 33: Polygnotos. - 450-440 B.C. - Upper area: P. ({¥JAMA@E) on a dolphin, holding a dolphin on one hand.

- 3.* (= Nereides 331* with bibl. and cross-references) Lecythe to fbl. New York, MMA 31.11.13. From Athenes. - ARV 1248, 9; 1688: P. of Eretria. - Circa 420 B.C.-P (inscribed), on a dolphin, holds the helmet of Achilles.

- 4.* (= Nereides 12 with bibl. and cross-references) Pyxis. New York, MMA 40.11.2. From Greece? - ARV 1213, 1: P. of London D 14. - About 435-430 B.C. - Seated P. (inscribed) receives a crown from >Glauke (I) (?).

- 5. (= Nereides 13 with bibl, = Theo I 1) Pyxis. Athens, Ephoria A 1877. From Athens, Eolou Street. - ARV 1707, 84%: P. de Kalliope. ~ About 430 B.C. - P. (inscr.) standing holding an exaleiptron.

- 6.* (= Nereides 10 with references, = Ploto 1*) Skyphos. Berlin, Staatl. Mus. V.I. 3244. From Sorrento. - ARV 1142: P. de Xenotimos; Add? 334 ~ About 430 B.C. ~ A: Eileithyia, Nereus, Eulimene. B: Thetis, Ploto offers a hare to D (inscr.; sakkos) seated at g.

- 7.* (= Kymathoe 2 with bibl. and cross-references) Aryballisque lekythos. Naples, Mus. Naz. 81849 (H 3352). - Kymathoe, Thetis, P. (WEMAOE, sic) standing towards dr., holding phiale and jug. Hermes, Achilles, Nereus. l .

- 8. (= Kymodoke 3 with references, = Peitho 10,= Pe- leus 179) Aryballe ft. lost. Formerly at Athens, priv. coll. - 1V*s. B.C. Struggle of Thetis and Peleus: only the inscription of his name remains of P.

- COMMENTARY

- P, whose name evokes the sea shores, appears on Attic vases with f.r. dated mostly between 450 and 420 B.C., mixed with her sceurs in very frequent scenes of the iconography of the Nereids (fight of Peleus and Thetis: 1, 8; transport of the weapons of Achill 2-3; interior scenes: 4-5). She has the usual appearance of the female figures of the time, dressed in a chiton and sometimes in a himation, and distinguished only by the inscription that designates her.

- She is often named on the figurative documents, without however presenting a personal iconography. She benefits, like Thetis, Amphitrite and Galateia of an individual myth in the literature, which frequently takes again the same topics as that of Thetis. Only one representation, with a difficult interpretation, highlights her (6).

- For the interpretation of the interior or gynecological scenes (4-5), >Nereides p. 788-789.

Tripp[edit]

- s.v. Aeacus, pp. 14–15

- Endeis bore two sons, Peleus and Telamon. Aeacus had a third son, Phocus, by the nereid Psamathe.

- s.v. Peleus, pp. 452–455

- According to Ovid [Metamorphoses 11.266–288, 11.346–406], Peleus went from Aegina to Trachis, where Ceyx, king of Oeta, entertained him. Psamathe, Phocus' sea-nymph mother, sent a wolf to destroy Peleus' flocks. The fugitive tried vainly to appease her with prayers and sacrifice. Finally, Psamathe's sister Thetis, who later married Peleus, interceded for him and Psamathe turned the wolf to stone.

- s.v. Proteus (2), pp. 502–503

- A king of Egypt. Proteus succeeded Pharos as king. He married the Nereid Psamathe, formerly Aeacus' mistress, and had by her a son, Theoclymenus, and a daughter, Eido, who later came to be called Theonoe.

- s.v. Psamathe, p. 503

- A Nereid. Psamathe bore a son, Phocus, to Aeacus, king of Aegina. The young man was killed by his half-brothers, Peleus and Telamon. Psamanthe sent a wolf to ravage the flocks of Peleus in Phthia or Trachis, but was persuaded by her sister Thetis to turn the animal to stone. Psamathe later married Proteus, king of Egypt, and bore two children, Theoclymenus and Eido (Theonoe). [Ovid, Metamorphoses, 11.346–406; Euripides, Helen, 4.13.]

Structure[edit]

- Family

- Mythology

- Sources

- Iconography

Subject[edit]

Parentage of Peleus and Telamon[edit]

Death of Phocus[edit]

Primary[edit]

BNJ[edit]

- commentary on 289 F4

- This is a well-known story, of which there were numerous versions, different in respect to who exactly had murdered Phokos (both brothers; Peleus only – this is the most widespread version – or Telamon only, a version present only here), in the way in which Phokos was killed, and in the reason for the murder (see S. Eitrem, ‘Phokos (3)’, RE 20.1 (1941), cols. 498-500; the long, detailed footnote of J.G. Frazer, Apollodorus. Library 2 (Cambridge, Ma 1921), 56-7, ad 3.13.6; and T. Gantz, Early Greek Myth: a Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources (Baltimore 1993), 222-3). Its Roman pendant, the story of the murder by Rhesos of his half-brother Similis during a hunt, and of the exile imposed on him by his father Gaius Maximus, supposedly culled from the third book of Aristokles’ Italika, is unknown, and clearly modelled on the basis of the Greek story (see BNJ 831 F 1 - but I cannot agree with M. Horster’s commentary to F 1, nor with her overall evaluation of Aristokles). Because the title Metamorphoses does not fit with the other works attributed to Dorotheos, Dübner in a note to Müller’s edition (C. Müller, Scriptores rerum Alexandri magni (Paris 1846) 156) proposed the correction of the author’s name to Theodoros, whose Metamorphoses are cited in Parallela minora 22A, Moralia 310F-311A; the same correction is proposed by M. van der Valk, Researches on the Text and the Scholia of the Iliad 1 (Leiden 1963), 406 n. 377. There is no reason to correct the text, which is perfectly sound as it is.

- The 6th-century epic poem Alcmeonis is our earliest source for the death of Phokos. In it, Phokos is killed by his half-brothers Telamon and Peleus: the first hits him with a discus, the second finishes him off with an axe (Alcmeonis F 1 Bernabé, Poetae Epici Graeci 1 (Leipzig 1987) = Alcmeonis F 1 West, Greek epic fragments = scholia to Euripides, Andromache 687). A similar version, in which, however, Peleus hits Phokos with the discus and Telamon finishes him off with a sword, is recorded in the scholia on Pindar, Nemean 5.14 and in Tzetzes’ commentary to Lykophron’s Alexandra 175.

- Pausanias 2.29.9 and 10.30.4, Ovid, Metamorphoses 11.267, and the A scholia to Homer, Iliad 16.14 all present Peleus as the murderer, and his action as intended. In Pseudo-Apollodoros, Library 3.12.6.11 Telamon is the main actor, as in (F 4) above: the two brothers plot against Phokos, but the lot falls on Telamon, who kills him. (In discussing Dorotheos’ version, (F 4) above, in which Telamon acts alone, Gantz, Early Greek Myth, 223 suggests that this version may have been intended to exonerate Peleus. While such an intent may have applied to the source followed on that point by Pseudo-Apollodoros, it seems to me very unlikely that the Parallela minora – or even Dorotheos’ Metamorphoses, if they ever existed – might have had such an intent). Finally, some sources present the death as accidental: in Pindar, Nemean 5.14-16, no specific details are given, but the brothers are unjustly exiled together, one supposes as a consequence of the accidental death of Phokos; the death is accidental also in Diodoros of Sicily 4.72.6 (with Peleus having thrown the discus and being sent into exile).

- Antoninos Liberalis, Metamorphoses 38, offers a complex narrative (related, if one trusts the manchette, to Nikander’s Heteroioumena (cf. BNJ 271-272)), which involves a metamorphosis. In Antoninus’ version, the two brothers kill Phokos ‘in secret’ – how the murder was perpetrated is not specified; they are then exiled; while in exile, Peleus unintentionally kills, during a hunt, his benefactor Eurytion, who has purified him; he has thus to leave again, and after other incidents brings together cattle and sheep as blood-price for Eurytion; but as the father of Eurytion, Iros, does not accept the price, the animals are left free. At this point, a wolf eats them all, and is by divine will changed into a stone. In Antoninus, the murder of Phokos is presented in the traditional way; but the second story, in which Peleus kills Eurytion during a boar-hunt, is interesting. Telamon is the hero of a similar adventure: according to Philostephanos, quoted as authority in the scholia D to Homer, Iliad 16.14 (Van Thiel), Peleus killed Phokos, and was sent into exile; as for Telamon, he killed involuntarily one of the participants in the hunt of the Calydonian boar, and thus was also sent into exile. In Pseudo-Apollodoros, Library 3.13.2, Peleus kills Eurytion, son of Actor, during the Calydonian boar-hunt. The unique version of Parallela minora might thus be the result of a confusion between these versions (so Frazer, Apollodorus 2.56-7), or also, as I prefer to think (with Jacoby, FGrH 3A, 392), of intentional readaptation. Note however that Lactantius, L. Caecilius Firmianus Placidus, Commentary to Statius, Thebaid 2.113, seems to hint at a version in which Peleus unwittingly killed Phokos during a hunt (he is comparing Tydeus, ‘pollutus … sanguine Melanippi fratris sui, quem in venatu incautus occiderat ut Peleus Phocum, …’; but in the commentary to the Thebaid 7.344 and 11.281, Lactantius Placidus names Peleus and Telamon together as murderers, without giving details as to how this was achieved): more variants than we can now track may have been circulating. As Peter Liddel points out to me, beyond issues of content, we may find a trace of the literary ambitions of the Pseudo-Plutarch in the parallelism preserved in the text of the Parallela minora, where Phokos moves from being presented as the beloved one (στεργομένου) to being the hated one (μισουμένου).

- Jacoby, FGrH 3A, 392 stresses the oddity of the absence of a metamorphosis in a story culled from a book titled Metamorphoses. As he points out, the notion that in an ampler version of the Parallela minora / in Dorotheos Phokos transformed himself in a seal, is a solution of despair; nor can a metamorphosis such as the one that occurs at the end of the version of Antoninus Liberalis 38 (the wolf who eats the cattle, and is then changed into stone) solve the problem. However, according to a tradition preserved by Pseudo-Apollodoros, Library 3.12.6, and by the scholiast to Euripides, Andromache 687, Phokos’ mother, the Nereid Psamathe, had transformed herself into a seal in attempting to escape the advances of Aiakos. While this cannot have figured in the story as narrated in Parallela minora, it is clear that transformations are part of the story’s overall landscape; in this sense, to give as source-reference a book on metamorphosis may have been an intended, allusive joke of Pseudo-Plutarch.

Frazer[edit]

- n. 14 to 3.16.2

- 14 As to the murder of Phocus and the exile of Peleus and Telamon, see Diod. 4.72.6ff. (who represents the death as accidental); Paus. 2.29.9ff.; Scholiast on Pind. N. 5.14(25); Scholiast on Eur. Andr. 687 (quoting verses from the Alcmaeonis); Scholiast on Hom. Il. xvi.14; Ant. Lib. 38; Plut. Parallela 25; Tzetzes, Scholiast on Lycophron 175 (vol. i. pp. 444, 447, ed. Muller); Hyginus, Fab. 14; Ov. Met. 11.266ff.; Lactantius Placidus on Statius, Theb. ii.113, vii.344, xi.281. Tradition differed on several points as to the murder. According to Apollodorus and Plutarch the murderer was Telamon; but according to what seems to have been the more generally accepted view he was Peleus. (So Diodorus, Pausanias, the Scholiast on Homer, one of the Scholiast on Eur. Andr. 687, Ovid, and in one passage Lactantius Placidus). If Pherecydes was right in denying any relationship between Telamon and Peleus, and in representing Telamon as a Salaminian rather than an Aeginetan (see above), it becomes probable that in the original tradition Peleus, not Telamon, was described as the murderer of Phocus. Another version of the story was that both brothers had a hand in the murder, Telamon having banged him on the head with a quoit, while Peleus finished him off with the stroke of an axe in the middle of his back. This was the account given by the anonymous author of the old epic Alcmaeonis; and the same division of labour between the brothers was recognized by the Scholiast on Pindar and Tzetzes, though according to them the quoit was handled by Peleus and the cold steel by Telamon. Other writers (Antoninus Liberalis and Hyginus) lay the murder at the door of both brothers without parcelling the guilt out exactly between them. There seems to be a general agreement that the crime was committed, or the accident happened, in the course of a match at quoits; but Dorotheus (quoted by Plut. Parallela 25) alleged that the murder was perpetrated by Telamon at a boar hunt, and this view seems to have been accepted by Lactantius Placidus in one place (Lactantius Placidus on Statius, Theb. ii.113), though in other places (Lactantius Placidus on Statius, Theb. vii.344 and xi.281) he speaks as if the brothers were equally guilty. But perhaps this version of the story originated in a confusion of the murder of Phocus with the subsequent homicide of Eurytion, which is said to have taken place at a boar-hunt, whether the hunting of the Calydonian boar or another. See below, Apollod. 3.13.2 with the note. According to Pausanias the exiled Telamon afterwards returned and stood his trial, pleading his cause from the deck of a ship, because his father would not suffer him to set foot in the island. But being judged guilty by his stern sire he sailed away, to return to his native land no more. It may have been this verdict, delivered against his own son, which raised the reputation of Aeacus for rigid justice to the highest pitch, and won for him a place on the bench beside Minos and Rhadamanthys in the world of shades.

Gantz[edit]

- pp. 222–3

- Returning to the three more certain sons, Peleus, Telamon, and Phokos, we come to the regrettable event alluded to in the fragment of the Alkmaionis, namely the death of Phokos at the hands of his two half-brothers. The Alk- maionis as quoted by a scholiast simply attests that Telamon struck Phokos on the head with a discus, and that Peleus then completed the deed, hitting him quickly in the back with an axe (fr 1 PEG). The context of such a reference is uncertain; probably it was utilized as something already familiar to the poem’s audience. Pindar also refers to the murder in Nemean 5, but quite obliquely, and as something he does not wish to discuss (Nem 5.6—12). No preserved title or even fragment suggests the existence of a tragedy on this promising material. All further details come from scholia and late sources such as Apollodoros and Pausanias; most of these agree that both men plotted the crime together, although there is some variation regarding whether one or the other or both together committed it. In Pausanias, for example, Peleus alone uses the discus to perform the slaying under the guise of training for athletic contests (2.29.9). So too, in the A scholia to Iliad 16.14, Peleus does the deed alone and flees to Cheiron, while Telamons exile is caused by the inadvertent slaying of a fellow hunter during the Kalydonian Boar Hunt. On the other hand, Plu- tarch (citing one Dorotheos) relates a version—Telamon takes Phokos out hunting and deliberately throws his spear at his brother—which might be in- tended to exonerate Peleus (Mor 311e). Two motives are reported, one that Peleus and Telamon were jealous because Phokos surpassed them in athletic skills (ApB 3.12.6; X And 687), the other that they wished to please their mother, who was angry at this offspring by another woman (Paus 2.29.9).?8 Some attempt was made to conceal the murder, but Aiakos discovered it, and both his remaining sons went into exile. Telamon indeed did try to defend himself, but his father refused to hear him, and he thus migrated to Salamis (Paus 2.29.10). Only Diodoros claims that the killing (by Peleus) was accidental (DS 4.72.6).

Hard[edit]

- p. 531

- Peleus and Telamon are exiled from Aegina for killing their half-brother Phokos

- For all his high principles, Aiakos mismanaged his family affairs and became estranged from his sons. He married Endeis, daughter of Cheiron (or Skeiron), who bore him his two legitimate children, PELEUS and TELAMON; but he also fathered a son out of wedlock by the Nereid Psamathe.91 On finding herself accosted by a mortal, the sea-nymph tried to escape his embrace by turning herself into a seal (phoke), but he kept a firm hold on her and caused her to conceive a son, PHOKOS, whom he reared as a member of his family.92 He was especially fond of Phokos and showed him such favour that his wife and legitimate sons grew increasingly resentful, until Peleus and Telamon eventually banded together to murder the intruder with the encouragement of their mother. Although accounts differ on whether Peleus or Telamon delivered the fatal blow or both did so jointly, it was generally agreed that they conspired together to cause his death. According to the usual tradition, one or the other killed Phokos by hurling a discus at his head while the three of them were exercising together. Other versions of the legend in which they were said to have killed him because they were jealous of his athletic prowess or simply by accident were plainly of secondary origin. Whatever the exact course of events, Aiakos sent Peleus and Telamon into exile on hearing of the death of Phokos, and never allowed them to set foot on Aegina again.93

- 91 Apollod. 3.12.6, Paus. 2.29.7, cf. Bacch 13.96–9 (two sons by Endeis), Pi. Nem. 5.8–13; Phokos as son by Psamathe, already Hes. Theog. 1003–5.

- 92 Apollod. 3.12.6, schol. Eur. Androm. 687.

- 93 Apollod. 3.12.6 (Telamon kills Phokos), Alcmaeonis fr. 1 Davies (Telamon strikes with discus, Peleus kills with axe), Paus. 2.29.7 (Peleus kills), D.S. 4.72.6 (Peleus kills accidentally).

Text[edit]

Old[edit]

- ... in Greek mythology, was a Nereid, one of the fifty daughters of the sea god Nereus and the Oceanid Doris. She was the mother of Phocus by Aeacus[1] and later became the wife of Proteus.[2] By the latter, she gave birth to a son, Theoclymenus, who became a king of Egypt, and a daughter, Theonoe (Eido).

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 11.398

- ^ In Euripides' tragedy Helen, Psamathe is married to king Proteus of Egypt.

New[edit]

Lead[edit]

In Greek mythology, Psamathe (Ancient Greek: Ψαμάθη) is a Nereid, one of the fifty daughters of the sea god Nereus and the Oceanid Doris. By Aeacus, the king of Aegina, she becomes the mother of a son, Phocus, and is later the wife of Proteus, king of Egypt.

Mythology[edit]

Peleus and Telamon are the sons of Aeacus by his wife Endeis.[note 1][1] The two of them kill their half-brother Phocus,[note 2][2] and they are subsequently exiled from Aegina by their father.[3] The second story which features Psamathe involves her sending of a wolf at the herds of Peleus, out of revenge for her son's death.[clarification note as to the origins of said "herds"?] After the wolf eats part of Peleus' herd, it is turned to stone by either Psamathe herself, or her sister Thetis.[4]

Footnotes[edit]

[note 1] The parentage of Peleus and Telamon [etc etc...]

[note 2] The manner in which Phocus is killed and by whom, as well as the motivation which vary between versions,For an extensive discussion of Phocus' death by his half-brothers, see BNJ, commentary on 289 F4; see also Gantz, pp. 222–3; Hard, p. 531; Frazer, n. 14 to 3.16.2. The specifics of his death and the motivations of his half-brothers vary between versions. [etc etc...]

References[edit]

- ^ Hard, p. 531.

- ^ The manner in which Phocus is killed and the motivations for his murder vary between versions. For an extensive discussion of Phocus' death by his half-brothers, see BNJ, commentary on 289 F4; see also Gantz, pp. 222–3; Hard, p. 531; Frazer, n. 14 to 3.16.2.

- ^ Gantz, pp. 223; Hard, p. 531.

- ^ (secondary sources ? ) Ovid, Metamorphoses 11.348–409 (pp. 144–149); Tzetzes on Lycophron, 175 (pp. 432–447); also Nicander apud Antoninus Liberalis, 38.

Iconography[edit]

- LIMC 1–8

Vases[edit]

LIMC 8059 (Psamathe 1)[edit]

- Description:

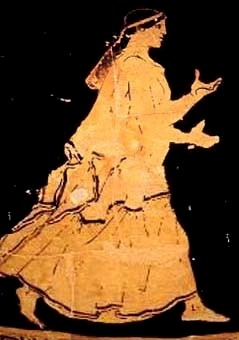

- During the fight between Thetis and Peleus, the following Nereids are fleeing: Nao, Psamathe, Kymatolege, Melite (I), Speo, Kymathoe and Glauke (I). Nereus runs towards the couple.

- Technique

- red figured

- Names

- Glauke I, Kymathoe, Kymatolege, Melite I, Nao, Nereus, Peleus, Psamathe, Speio

Szabados

- p. 568

- Struggle of Thetis and Peleus: Nereus and seven Nereids, including P., current (inscribed names).

Newton

- p. 3

- 2. A vase engraved (Monumenti Inediti del Instituto Archeologico I, Tav. 38). On this vase we have in the centre the struggle of Peleus and Thetis, with Nereids on each side, over whom area inscribed their names, Cymathoe, Psamathe, Cymatolege, Glauke, Speo, Melite, and Nao. In this scene Nereus, the father of Thetis, appears on the left.

LIMC 387 (Psamathe 2)[edit]

- Description:

- Upper panel: Thetis and Nereides on marine monsters, carrying the arms of Achilleus. Nausithoe and Psamathe are seated on a dolphins. B: Prothesis of Patroklos? Patroklos on a kline, a standing woman (Briseis?) and Talthybios.

- Technique

- red figured

- Names

- Glauke I, Kymathoe, Kymatolege, Melite I, Nao, Nereus, Peleus, Psamathe, Speio

Szabados

- p. 568

- P. ({¥JAMA@E) on a dolphin, holding a dolphin on one hand.

Richter

- p. 175

- ... from the right we see approaching Thetis, the mother of Achilles, and her Nereid sisters, bringing the armor made by Hephaistos. They are riding across the sea on dolphins ... then Psamathe ([Inscription]) her head in three-quarter view, with an Attic helmet ...

LIMC 10251 (Psamathe 3)[edit]

- Description:

- Middle panel: Thetis and seven other Nereids sitting on dolphins. The Nereids Klymene (I), Psamathe, Galateia and Kymodoke are carrying the new arms to Achilleus. The seventh Nereid, sitting on the left, is named Euploia. In the lower panel an amazonomachie. Some of the figures are named. Eupolis (I) is a Greek adversary of Doris. The amazon Klymene (VIII) is shown in oriental dress. Hippolyte attacks Phaleros.

- Technique

- red figured and white-ground

- Names

- Achilleus, Amazones, Amynomene, Charope, Doris II, Eumache, Euploia, Eupolis I, Galateia, Hippolyte I, Klymene I, Klymene VIII, Kymodoke, Mimnousa, Nereides, Patroklos, Phaleros, Psamathe, Theseus, Thetys I

Szabados

- p. 568

- [P.] on a dolphin, holds the helmet of Achilles.

LIMC 12954 (Psamathe 4)[edit]

- Description

- Six Nereids in an indoor scene. The Nereids are: Aktaie (I), Beroie, Galene (I), Kymodoke, Glauke (I) and Psamathe.

Szabados

- p. 568

- Seated P. (inscribed) receives a crown from >Glauke (I) (?).

LIMC 4844 (Psamathe 5)[edit]

- Description:

- Galene, Alexo with box and Psamathe, standing, holding exaleiptron. Thetis with mirror, Eulimene, Glauke handing over a box to Kymododoe, Theo (I) with alabastron, Aura and Chryseis wir exaleiptron.

- Technique

- red figured

- Names

- Nereides, Psamathe, Theo I, Thetis

Szabados

- p. 568

- P. (inscr.) standing holding an exaleiptron.

LIMC 10893 (Psamathe 6)[edit]

- Description:

- Nereus and the Nereids. A: Eulimene, Nereus seated, and before him Eileithyia with a dolphin. Her hair is tied at the nape with a red ribbon. By the flower on the handles in red the inscription HILITHYA. Ploto offers a hare to Psamanthe.

Szabados

- p. 568

- Eileithyia, Nereus, Eulimene. B: Thetis, Ploto offers a hare to P. (inscr.; sakkos) seated at g.

LIMC 1713 (Psamathe 7)[edit]

- Description:

- Lower frieze: Nine fleeing companions of Oreithyia (I) - two of them with balls - and Erechtheus (standing). Upper frieze: Kymathoe, standing, putting her hands on the shoulders of the seated Thetis. Close to them Psamathea, holding a phiale. The seated Nereus offers a crown to Achilleus, between them is Hermes. All figures are named.

Szabados

- p. 568

- Kymathoe, Thetis, P. (WEMAOE, sic) standing towards dr., holding phiale and jug. Hermes, Achilles, Nereus. l .

LIMC 12127 (Psamathe 8)[edit]

- Description:

- Fight between Thetis and Peleus in the presence of Nereides (Kymodoke, Psamathe) and gods (Aphrodite, Eros, Pan, Athena, Poseidon).

- Names

- Aphrodite, Kymodoke, Peitho, Peleus, Psamathe

Szabados

- p. 568

- Struggle of Thetis and Peleus: only the inscription of his name remains of P.

Subject[edit]

Fight between Peleus and Thetis[edit]

- LIMC 8059 (Psamathe 1); Beazley Archive, 213890; Newton, p. 3

- – Among the Nereids fleeing from the couple

Transportation of the Weapons of Achilles[edit]

- LIMC 387 (Psamathe 2); Beazley Archive, 213890; Richter, p. 175

- – Riding on a dolphin, holding an Attic helmet

- – Riding on a dolphin, holding Achilles' helmet

Other[edit]

Images[edit]

Genealogy[edit]

| Psamathe's family tree | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- ^ LIMC 8059 (Psamathe 1).

- ^ For more detailed charts of Aeacus' genealogy, see Hard, p. 711, table 18, and Grimal, p. 550, table 30.

![Psamathe, detail of a vase depicting the struggle between Peleus and Thetis. Psamathe is among the Nereids fleeing from the couple.[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/73/Psamathe.jpg/126px-Psamathe.jpg)