User:Mr. Ibrahem/Reflex syncope

{{#unlinkedwikibase:id=Q2667159}}

| Reflex syncope | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Neurally mediated syncope, neurocardiogenic syncope[1][2] |

| |

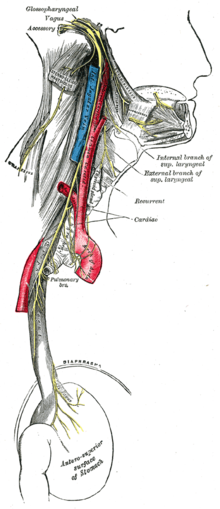

| Vagus nerve | |

| Specialty | Neurology, cardiovascular |

| Symptoms | Loss of consciousness before which there may be sweating, decreased ability to see, ringing in the ears[1][2] |

| Complications | Injury[1] |

| Duration | Brief[1] |

| Types | Vasovagal, situational, carotid sinus syncope[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after ruling out other possible causes[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Arrhythmia, orthostatic hypotension, seizure, hypoglycemia[1] |

| Treatment | Avoiding triggers, drinking sufficient fluids, exercise, cardiac pacemaker[2] |

| Medication | Midodrine, fludrocortisone[4] |

| Frequency | > 1 per 1,000 people per year[1] |

Reflex syncope is a brief loss of consciousness due to a neurologically induced drop in blood pressure.[2] Before an affected person passes out, there may be sweating, a decreased ability to see, or ringing in the ears.[1] Occasionally, the person may twitch while unconscious.[1] Complications of reflex syncope include injury due to a fall.[1]

Reflex syncope is divided into three types: vasovagal, situational, and carotid sinus.[2] Vasovagal syncope is typically triggered by seeing blood, pain, emotional stress, or prolonged standing.[5] Situational syncope is often triggered by urination, swallowing, or coughing.[2] Carotid sinus syncope is due to pressure on the carotid sinus in the neck.[2] The underlying mechanism involves the nervous system slowing the heart rate and dilating blood vessels, resulting in low blood pressure and thus not enough blood flow to the brain.[2] Diagnosis is based on the symptoms after ruling out other possible causes.[3]

Recovery from an episode happens without specific treatment.[2] Prevention of episodes involves avoiding a person's triggers.[2] Drinking sufficient fluids, salt, and exercise may also be useful.[2][4] If this is insufficient for treating vasovagal syncope, medications such as midodrine or fludrocortisone may be tried.[4] Occasionally, a cardiac pacemaker may be used as treatment.[2] Reflex syncope affects at least 1 in 1,000 people per year.[1] It is the most common type of syncope, making up more than 50% of all cases.[2]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Aydin, MA; Salukhe, TV; Wilke, I; Willems, S (26 October 2010). "Management and therapy of vasovagal syncope: A review". World Journal of Cardiology. 2 (10): 308–15. doi:10.4330/wjc.v2.i10.308. PMC 2998831. PMID 21160608.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Adkisson, WO; Benditt, DG (September 2017). "Pathophysiology of reflex syncope: A review". Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 28 (9): 1088–1097. doi:10.1111/jce.13266. PMID 28776824.

- ^ a b Brignole, Michele; Benditt, David G. (2011). Syncope: An Evidence-Based Approach. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 158. ISBN 9780857292018. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Shen, WK; Sheldon, RS; Benditt, DG; Cohen, MI; Forman, DE; Goldberger, ZD; Grubb, BP; Hamdan, MH; Krahn, AD; Link, MS; Olshansky, B; Raj, SR; Sandhu, RK; Sorajja, D; Sun, BC; Yancy, CW (1 August 2017). "2017 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society". Circulation. 136 (5): e25–e59. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000498. PMID 28280232.

- ^ "Syncope Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.