User:Mr. Ibrahem/Serotonin syndrome

| Serotonin syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Serotonin toxicity, serotonin toxidrome, serotonin sickness, serotonin storm, serotonin poisoning, hyperserotonemia, serotonergic syndrome, serotonin shock |

| |

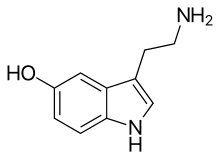

| Serotonin | |

| Specialty | Critical care medicine, psychiatry |

| Symptoms | High body temperature, agitation, increased reflexes, tremor, sweating, dilated pupils, diarrhea[1][2] |

| Usual onset | Within a day[2] |

| Causes | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), amphetamines, pethidine (meperidine), tramadol, dextromethorphan, ondansetron, cocaine[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and medication use[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, malignant hyperthermia, anticholinergic toxicity, heat stroke, meningitis[2] |

| Treatment | Active cooling[1] |

| Medication | Benzodiazepines, cyproheptadine[1] |

| Frequency | Unknown[3] |

Serotonin syndrome (SS) is a group of symptoms that may occur with the use of certain serotonergic medications or drugs.[1] The degree of symptoms can range from mild to severe.[2] Symptoms in mild cases include high blood pressure and a fast heart rate; usually without a fever.[2] Symptoms in moderate cases include high body temperature, agitation, increased reflexes, tremor, sweating, dilated pupils, and diarrhea.[1][2] In severe cases body temperature can increase to greater than 41.1 °C (106.0 °F).[2] Complications may include seizures and extensive muscle breakdown.[2]

Serotonin syndrome is typically caused by the use of two or more serotonergic medications or drugs.[2] This may include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), amphetamines, pethidine (meperidine), tramadol, dextromethorphan, buspirone, L-tryptophan, 5-HTP, St. John's wort, triptans, ecstasy (MDMA), metoclopramide, ondansetron, or cocaine.[2] It occurs in about 15% of SSRI overdoses.[3] It is a predictable consequence of excess serotonin on the central nervous system (CNS).[4] Onset of symptoms is typically within a day of the extra serotonin.[2]

Diagnosis is based on a person's symptoms and history of medication use.[2] Other conditions that can produce similar symptoms such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome, malignant hyperthermia, anticholinergic toxicity, heat stroke, and meningitis should be ruled out.[2] No laboratory tests can confirm the diagnosis.[2]

Initial treatment consists of discontinuing medications which may be contributing.[1] In those who are agitated, benzodiazepines may be used.[1] If this is not sufficient, a serotonin antagonist such as cyproheptadine may be used.[1] In those with a high body temperature active cooling measures may be needed.[1] The number of cases of serotonin syndrome that occur each year is unclear.[3] With appropriate treatment the risk of death is less than one percent.[5] The high-profile case of Libby Zion, who is generally accepted to have died from serotonin syndrome, resulted in changes to graduate medical education in New York State.[4][6]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ferri, Fred F. (2016). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1154–1155. ISBN 9780323448383. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Volpi-Abadie J, Kaye AM, Kaye AD (2013). "Serotonin syndrome". The Ochsner Journal. 13 (4): 533–40. PMC 3865832. PMID 24358002.

- ^ a b c Domino, Frank J.; Baldor, Robert A. (2013). The 5-Minute Clinical Consult 2014. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1124. ISBN 9781451188509. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ^ a b Boyer EW, Shannon M (March 2005). "The serotonin syndrome" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (11): 1112–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041867. PMID 15784664. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-18.

- ^ Friedman, Joseph H. (2015). Medication-Induced Movement Disorders. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 9781107066007. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ^ Brensilver JM, Smith L, Lyttle CS (September 1998). "Impact of the Libby Zion case on graduate medical education in internal medicine". The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, New York. 65 (4): 296–300. PMID 9757752.