User:Nissafreed

Feminist science fiction is a subgenre of science fiction which is focused on examining women’s roles in society. Feminist sci fi poses questions about important social issues such as how society constructs gender roles, the role reproduction plays in defining gender, and the unequal political and personal power of men and women. Feminist science fiction often illustrates these themes using utopias to explore a society in which gender differences or gender power imbalances do not exist; or dystopias to explore worlds in which gender inequalities are intensified, thus highlighting the need for feminist work to continue.[1] According to Gary Westfahl:

"Science fiction and fantasy serve as important vehicles for feminist throught, particularly as bridges between theory and practice. No other genres so actively invite representations of the ultimate goals of feminism: worlds free of sexism, worlds in which women's contributions (to science) are recognized and valued, worlds in which the diversity of women's desire and sexuality, and worlds that move beyond gender."[2]

Literature[edit]

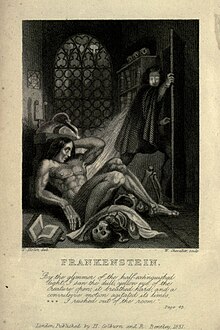

Women writers are often regarded as outside the mainstream of science fiction although Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, published in 1818, is often considered to be the first work of modern science fiction.[3] This may be due to a tradition of pulp science fiction (see pulp magazines) from the 1920-30’s in which an exaggerated view of masculinity and sexist portrayals of women were key to the genre.[4] In the 1960’s the genre of science fiction took a different turn, combining its existing sensationalism with political and technological critique of society. With the advent of feminism, questioning women’s roles became fair game to this "subversive, mind expanding genre."[5]

Two key early texts are Ursula K. Le Guin's The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) and Joanna Russ' The Female Man (1970). They serve to highlight the socially constructed nature of gender roles by creating utopias that do away with this issue by creating genderless societies.[6] In The Handmaid's Tale, Margaret Atwood tells a dystopic tale of a society in which women are stripped of all freedom, which serves to highlight the continued importance of feminism.[7] Octavia Butler poses complicated questions about the nature of race and gender in her book Kindred (1979). This literary form is not limited to Western feminism. The Sultana's Dream, depicting a gender-reversed purdah in an alternate and technolgically futuristic world, was published in 1905 by Bengali Muslim feminist Roquia Sakhawat Hussain.

Feminist science fiction is sometimes used at the university level to teach about the role of social constructs in understanding gender.[8] More often the role of feminist science fiction is to pose questions that lead us to examine the conceptual bedrock of societal institutions such as motherhood, femininity, and the political power structure of the world we live in.

Examples in Prose

- The Female Man by Joanna Russ

- The Fifth Sacred Thing by Starhawk

- The Gate to Women's Country by Sheri S. Tepper

- Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- The Handmaid's Tale and Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood

- "Houston, Houston, Do You Read?" by James Tiptree, Jr.

- Gormglaith, by Heidi Wyss

- Kindred by Octavia Butler

- The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. LeGuin

- Motherlines and Walk to the End of the World by Suzy McKee Charnas

- Native Tongue (1984), The Judas Rose (1987), and Earthsong (1993), by Suzette Haden Elgin

- Oy Pioneer! by Marleen S. Barr

- Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler

- The Shore of Women by Pamela Sargent

- The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin

- Sultana's dream by Roquia Sakhawat Hussain

- The Ship Who Searched by Mercedes Lackey

Comic Books and Graphic Novels[edit]

Feminist science fiction embraced the globally popular new medium of anime and graphic novels. In the early 1960s, Marvel Comics already contained some strong female characters, although they often suffered from stereotypical female weakness such as fainting after intense exertion.[9] By the 1980s, true female heroes started to emerge on the pages of comics.[10]

One of the first appearances of a strong female character was that of Wonder Woman co-created by husband and wife team William Moulton Marston and Elizabeth Holloway Marston. In December 1941 Wonder Woman came to life on the pages of All Star Comics volume # 8. The character later spawned a television series starring Lynda Carter and played a role in animated series such as Super Friends and the Justice League. A motion picture adaptation is currently underway.

Characters such as Sailor Moon, a teenager with the ability to transform into a magical girl who battles the evil forces of the universe to protect the ones that she loves, splashed onto the page of comic book history in February 1992. This led to other positive female heroes taking shape in comic books the world over.

Examples Comic books and Graphic Novels

- Akiko by Mark Crilley

- Doom Patrol by Rachel Pollack

- Finder by Carla Speed McNeil

- Hawk and Dove by Barbara Kesel

- Meridian by Barbara Kesel

- Supergirl by Peter David

- Tank Girl by Jamie Hewlett

- Wonder Woman by William Moulton and Sadie Holloway Marston

- Get Your Tongue Out of My Mouth, I'm Kissing You Goodbye by Cynthia Heimel

- Fushigi Yuugi by Yuu Watase

- Sailor Moon by Naoko Takeuchi

- Silent Möbius by Kia Asamiya

Film and Television[edit]

Feminist science fiction in film is the focus of identifying the tensions of feminism within the medium of film. Film could be anything from television, to mainstream Hollywood blockbusters. Just recently has the concept of feminism been acknowledged as a subgenre of science fiction. The beginning of this came from men going off to World War II, and the women being left behind to take on the scientific roles that the men left behind. This notion of women being able to take on these roles greatly influenced the ways that film was constructed thereafter.[11] Feminist science fiction in film helps to show gender roles and relationships that are portrayed. The films suggest new ideas of thinking about social constructs and the ways that feminists influence science.[12] These social constructions about the roles of males and females are creatively being broken down and questioned. Feminist science fiction leaves a window of opportunity to challenge the norms of society and suggest new standards of the ways societies view gender.[13] It deconstructs the male/female categories and shows that there is a difference between female roles verses feminine roles. Feminism influences the film industry with the progression of the science fiction genre.[14]

Some examples of FSF in Film:

- Wonder Woman (T.V. series)

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer (T.V. series)

- Xena: Warrior Princess (T.V series)

- The Handmaid’s Tale (1990)

- The Stepford Wives (1975)

Podcasts[edit]

Podcasts are one of the newest ways that science fiction is currently being explored. New writers are using podcasts to produce more material and expand the boundary of the genre.

Examples in Podcasts

Notes[edit]

- ^ Westfahl, Gary. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Greenwood Press, 2005: 289-290

- ^ Westfahl, Gary. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Greenwood Press, 2005:291

- ^ Stableford, Brian (2005). The A to Z of Science Fiction Literature. Scarecrow Press, 114.

- ^ Clute, John (1995). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Martin’s Griffin, 1344.

- ^ Clute, John (1995). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Martin’s Griffin, 424.

- ^ Westfahl, Gary. The Greenwood Encylcopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Greenwood Press, 2005: 290.

- ^ Sturgis, Susanna. Octavia E. Butler: June22, 1947-February 24, 2006: The Women's Review of Books, 23(3): 19, May 2006.

- ^ Lips, Hilary M. Using Science Fiction to Teach the Psychology of Sex and Gender: Teaching of Psychology 1990, Vol. 17, No. 3, Pages 197-198

- ^ Wright, Bradford (2003). Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 219.

- ^ Wright, Bradford (2003). Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 221.

- ^ Answers.com. Science Fiction. Feb 1. 2007.http://www.answers.com/topic/science-fiction

- ^ Miniscule, Caroline. The Thunder Child. Science Fiction and Fantasy Web Magazine and Sourcebooks. Fiction Book Reviews. “Stand By For Mars!”. http://thethunderchild.com/Reviews/Books/NonFiction/FilmStudies/Women50s.html

- ^ Westfahl, Gary. “Feminism”. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: themes, works and wonders. Westport, Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data, 2005. 289-291.

- ^ Hollinger, Veronica. “Feminist Theory and Science Fiction”. The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003. 125-134.

External links[edit]

- Feminist Science Fiction

- The Secret World Chronicle

- Variant Frequencies

- Escape Pod

- Geek Fu Action Grip