User:PNSMurthy/The Longest and Largest Theropods and Sauropods

Here is my list in the making :

Introduction[edit]

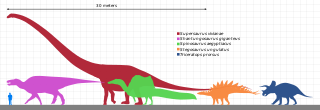

Size has been one of the most fascinating aspects of dinosaur paleontology to the general public and to professional scientists. Dinosaurs show some of the most extreme variations in size of any land animal group, ranging from the tiny hummingbirds, which can weigh as little as three grams, to the extinct titanosaurs, which could weigh as much as 90 tonnes (89 long tons; 99 short tons).[1]

Scientists will probably never be certain of the largest and smallest dinosaurs. This is because only a small fraction of animals ever fossilize, and most of these remain buried in the earth and will never be found. Few of the specimens that are recovered are complete skeletons, and impressions of skin and other soft tissues are rarely discovered. Rebuilding a complete skeleton by comparing the size and morphology of bones to those of similar, better-known species is an inexact art, and reconstructing the muscles and other organs of the living animal is, at best, a process of educated guesswork, and never perfect.[2] Weight estimates for dinosaurs are much more variable than length estimates, because estimating length for extinct animals is much more easily done from a skeleton than estimating weight. Estimating weight is most easily done with the laser scan skeleton technique that puts a "virtual" skin over it, but even this is only an estimate.[3]

The latest evidence suggests that dinosaur average size varied through the Triassic, early Jurassic, late Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, and dinosaurs probably only became widespread during the Jurassic.[4] Predatory theropod dinosaurs, which occupied most terrestrial carnivore niches during the Mesozoic, most often fall into the 100- to 1,000-kilogram (220 to 2,200 lb) category when sorted by estimated weight into categories based on order of magnitude, whereas recent predatory carnivoran mammals peak in the 10- to 100-kilogram (22 to 220 lb) category.[5] The mode of Mesozoic dinosaur body masses is between one and ten metric tonnes.[6] This contrasts sharply with the size of Cenozoic mammals, estimated by the National Museum of Natural History as about 2 to 5 kg (4.4 to 11.0 lb).[7]

§Taken from the Dinosaur size article

Record sizes[edit]

The sauropods were the longest and heaviest dinosaurs. For much of the dinosaur era, the smallest sauropods were larger than anything else in their habitat, and the largest were an order of magnitude more massive than anything else that has walked the Earth since. Giant prehistoric mammals such as Paraceratherium and Palaeoloxodon (the largest land mammals ever discovered[8]) were dwarfed by the giant sauropods, and only modern whales surpass them in weight, though they live in the oceans.[9] There are several proposed advantages for the large size of sauropods, including protection from predation, reduction of energy use, and longevity, but it may be that the most important advantage was dietary. Large animals are more efficient at digestion than small animals, because food spends more time in their digestive systems. This also permits them to subsist on food with lower nutritive value than smaller animals. Sauropod remains are mostly found in rock formations interpreted as dry or seasonally dry, and the ability to eat large quantities of low-nutrient browse would have been advantageous in such environments.[10]

One of the tallest and heaviest dinosaurs known from good skeletons is Giraffatitan brancai (previously classified as a species of Brachiosaurus). Its remains were discovered in Tanzania between 1907 and 1912. Bones from several similar-sized individuals were incorporated into the skeleton now mounted and on display at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin;[11] this mount is 12–13.27 metres (39.4–43.5 ft) tall and 21.8–22.5 metres (72–74 ft) long,[12][13][14] and would have belonged to an animal that weighed between 30,000 to 60,000 kilograms (66,000 to 132,000 lb). One of the longest complete dinosaurs is the 27-metre-long (89 ft) Diplodocus, which was discovered in Wyoming in the United States and displayed in Pittsburgh's Carnegie Natural History Museum in 1907.[15]

There were larger dinosaurs, but knowledge of them is based entirely on a small number of fragmentary fossils. Most of the largest herbivorous specimens on record were discovered in the 1970s or later, and include the massive titanosaur Argentinosaurus huinculensis, which is the largest dinosaur known from uncontroversial evidence, estimated to have been 50–96.4 metric tons (55.1–106.3 short tons)[16] and 30–39.7 m (98–130 ft) long.[17][18] Some of the longest sauropods were those with exceptionally long, whip-like tails, such as the 29–33.5-metre-long (95–110 ft) Diplodocus hallorum[10][18] (formerly Seismosaurus) and the 33- to 35-metre-long (108–115 ft) Supersaurus.[19][18]

In 2014, the fossilized remains of a previously unknown species of sauropod were discovered in Argentina.[20] The titanosaur, named Patagotitan mayorum, would have been around 40m long and weighed around 77 tonnes, larger than any other previously found sauropod. The specimens found were remarkably complete, significantly more so than previous titanosaurs. Research as of 2017 estimated Patagotitan to have been 37 m (121 ft) long [21] It has also been suggested that Patagotitan is not necessarily larger than Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus.[22]

Tyrannosaurus was for many decades the largest and best known theropod to the general public. Since its discovery, however, a number of other giant carnivorous dinosaurs have been described, including Spinosaurus, Carcharodontosaurus, and Giganotosaurus.[23] These large theropod dinosaurs rivaled or even exceeded Tyrannosaurus in size, though more recent studies show some indication that Tyrannosaurus, although shorter, was the heavier predator. Specimens such as Sue and Scotty are both estimated to be the most massive theropods known to science. There is still no clear explanation for exactly why these animals grew so much larger than the land predators that came before and after them.

The largest extant theropod is the common ostrich, up to 2.74 metres (9 ft 0 in) tall and weighs between 63.5 and 145.15 kilograms (140.0 and 320.0 lb).[24]

The smallest non-avialan theropod known from adult specimens may be Anchiornis huxleyi, at 110 grams (3.9 ounces) in weight and 34 centimetres (13 in) in length.[25] However, some studies suggest that Anchiornis was actually an avialan.[26] The smallest dinosaur known from adult specimens which is definitely not an avialan is Parvicursor remotus, at 162 grams (5.7 oz) and measuring 39 centimetres (15 in) long.[27] When modern birds are included, the bee hummingbird Mellisuga helenae is smallest at 1.9 g (0.067 oz) and 5.5 cm (2.2 in) long.[28]

Recent theories propose that theropod body size shrank continuously over the past 50 million years, from an average of 163 kilograms (359 lb) down to 0.8 kg (1.8 lb), as they eventually evolved into modern birds. This is based on evidence that theropods were the only dinosaurs to get continuously smaller, and that their skeletons changed four times faster than those of other dinosaur species.[29][30]

The List of Longest Theropods[edit]

Sizes are given with a range, where possible, of estimates that have not been contradicted by more recent studies. In cases where a range of currently accepted estimates exist, sources are given for the sources with the lowest and highest estimates, respectively, and only the highest values are given if these individual sources give a range of estimates. Some other giant theropods are also known; for example, a theropod trackmaker in Morocco that was perhaps between 10 and 19 metres (33 and 62 ft) long, but the information is too scarce to make precise size estimates.[31][32]

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus - 15 - 18 meters[33] (upper estimate is likely inaccurate)

Sigillmassosaurus brevicolius - 14.5[34] - 17 meters [citation needed](upper estimate is likelily inaccurate)

Giganotosaurus carollini - 12[citation needed] - 14.2 meters[35][36]

Carcheradontosaurus saharicus - 11 [citation needed] - 13.8 meters[37][38]

The 19IGR Trackmaker - 13.6[citation needed] - 15.7 meters[39](upper estimate not used for various inaccuracies)

Carcharadontosaurus iguidensis - 10[40] - 13 meters[citation needed]

Tyranosaurus rex - 10 - 12.6 meters[41]

Oles Megalasurine Trackmaker - 12.5 meters[42]

Mapusaurus rosea - 10[43] - 12.4 meters [citation needed]

'Tajakistan Theropod' - 12.4 meters [44]?

Oxalia quilembensis - 10.5[citation needed] - 12.4 meters[45]

"Titanovenator" 12.35 meters[44]?

Jurabrontes zigongensis - 12.3 meters[46]

Saurophaganax maximus - 12.3[citation needed] - 14 meters[47] [48][49](might be a junior synonym of Allosaurus)

NMHG-8501 - 12 - 12.25 meters[50]

Tyrannotitan chubutensis - 10[citation needed] - 12.25 metres[51][52]

Chilliantosaurus tshukiensis - 11[53] - 12.2 metres[citation needed]

Siats meekororum - 11.4 metres (juvenile)[54] - 12.18 metres (adult)?[55]

Dinocheirus mirficus - 12.1[56][57] - 15 meters[58] (upper estimate unused because of two estimates supporting lower size)

Epanterias ampleuxus - 10 - 12.1 meters[59] (might be junior synonym of Allosaurus)

Bahariosaurus ingens - 12.05 metres[60]

cf. Zhuchengtyrannus magnus - 12.05 meters[61]

Proedinodon mongoliensis - 10 - 11.95 meters[44]

'Edmarka Rex' - 11.9 meters[39](might be junior synonym of Torvosaurus)

Acrocanthosaurus atokensis - 10 - 11.9 meters[62]

Sauroniops pachytolus - 9[63] - 11.8 meters[64](might be junior synonym of Carcheradontosaurus, maybe even C.Saharicus or C.Iguidensis)

Tarbosaurus bataar - 10[65]- 11.7 meters[citation needed]

To be Continued and Improved

List of Heaviest Sauropods[edit]

Sauropodomorph size is difficult to estimate given their usually fragmentary state of preservation. Sauropods are often preserved without their tails, so the margin of error in overall length estimates is high. Mass is calculated using the cube of the length, so for species in which the length is particularly uncertain, the weight is even more so. Estimates that are particularly uncertain (due to very fragmentary or lost material) are preceded by a question mark. Each number represents the highest estimate of a given research paper. One large sauropod, Maraapunisaurus fragillimus, was based on particularly scant remains that have been lost since their description by paleontologists in 1878. Analysis of the illustrations included in the original report suggested that M. fragillimus may have been the largest land animal of all time, possibly weighing 100–150 t (110–170 short tons) and measuring between 40–60 m (130–200 ft) long.[18][66] One later analysis of the surviving evidence, and the biological plausibility of such a large land animal, suggested that the enormous size of this animal was an over-estimate due partly to typographical errors in the original report.[67] This would later be challenged by a different study, which argued Cope's measurements were genuine and there's no basis for assuming typographical errors. The study, however, also reclassified the species and correspondingly gave a much lower length estimate of 30.3 metres (99 ft) and a mass of 78.5 t (86.5 short tons).[68]

Generally, the giant sauropods can be divided into two categories: the shorter but stockier and more massive forms (mainly titanosaurs and some brachiosaurids), and the longer but slenderer and more light-weight forms (mainly diplodocids).

Because different methods of estimation sometimes give conflicting results, mass estimates for sauropods can vary widely causing disagreement among scientists over the accurate number. For example, the titanosaur Dreadnoughtus was originally estimated to weigh 59.3 tonnes by the allometric scaling of limb-bone proportions, whereas more recent estimates, based on three-dimensional reconstructions, yield a much smaller figure of 22.1–38.2 tonnes.[69]

Uncited for now (I am still uncovering the citations)

Unknown French Monster Titanosaur First specimen – 135 tonnes

1.) Maraapunisaurus Fragilimus – (62 -) 120 tonnes

Bruhathkayosaurus Maltei – 80 – 110 tonnes

Unnamed Australian Titanosaur specimen – 80 – 100 tonnes

Unnamed Giant Mamenchiosaur – 80 – 100 tonnes

Unnamed Museo de La Plata Sauropod – 80 – 100 tonnes

2.) Argentinosaurus Huinculensis – 65 – 100 tonnes

MUCPv-251 – 85 - 94 tonnes

3.) Puertosaurus Ruelli – (45-) 90 tonnes

‘Argyrosaurus’ specimen – 85 tonnes

Charente Monster Sauropod – 85 tonnes

4.) Alamasaurus Sanjuanensis – 40 – 85 tonnes

Unknown French Monster Titanosaur Second specimen – 80 (– 115 tonnes)

Unnamed Moroccan Sauropod – 80 tonnes

5.) Barosaurus Lentos – (12.2–) 80 tonnes

6.) Mamenchisaurus Sinocanadorum – (20-) 50 - 78 tonnes

Otegosaurus specimen – 78 tonnes

7.) Patogotitan Mayorum – 66 – 77 tonnes

‘Nemegtosaurus’ Sacrum – 77 tonnes

8.) Notocolossus Gonzalezparejasi – 50 – 74 tonnes

Unnamed Species – 72 tonnes

‘Antarctosaurus Giganteous’ – 45 - 72 tonnes

Fusiosaurus Zhaoi – (30 –) 70 tonnes

9.) Ruyangosaurus Giganteous – 68 (-100) tonnes

10.) Dreadnaughtus Scharni – (20-) 65 tonnes

‘Aegyptosaurus’ specimen – 65 tonnes

11.) Parralititan Stromeri – (40-) 64 tonnes

Breviparopus trackmaker – 48 - 62 tonnes

12.) Apatosaurus Ajax – (30-) 60 tonnes

13.) Sauroposeidin Proteles – 60 tonnes

‘Angloposeidin’ – 60 tonnes

‘Parabrontopodus’ – 60 tonnes

‘The Archbishop’ – 60 tonnes

14.) Brachiosaurus Alithorax – 35 – 55 tonnes

Unnamed MPM-PV-39 - 55 tonnes

Malakhelisaurus Mianwali – 55 tonnes

Supersaurus Vivianie – 55 tonnes

‘Chuangjesaurus’ – 50 – 55 tonnes

Yummenlong Ruyangensis – (38-) 54 tonnes

Abbydosaurus Macintoshi – 52 tonnes

‘Seismosaurus’ Longus / Hallorum – 30 – 52 tonnes (-100 tonnes)

15.) Huangetitan Ruyungensis – 40 – 50 tonnes

16.) Turiasaurus riodevensis – 50 tonnes

Unknown French Monster Titanosaur Third specimen – 50 tonnes

17.) Argyrosaurus superbus – 50 tonnes

Ultrasauripus – 50 tonnes

‘Dinheirosaurus’ – 50 tonnes

Galveosaurus Herreroi – 50 tonnes

Rapetosaurus specimen – 50 tonnes

Huabeisaurus specimen – 30 – 50 tonnes

Xinjiangtitan Shanshanesis – (25 -) 48 tonnes

18.) Futlongkosaurus Dukei – (29 -) 48 (-70) tonnes

Losillasaurus Giganteus – 47 tonnes

‘Francoposeidon’ – 47 tonnes

‘Gara Samana’ trackmaker – 47 tonnes

19.) Camarasaurus Supremus – 47 tonnes

20.) Girafatitan Branchai – 45 (-70) tonnes

Ultrasaurus Singulatus – 45 tonnes

Unnamed Footprint – 45 tonnes

Plagne trackmaker – 45 tonnes

‘Puertosaurus’ Taqueti – 41 tonnes

Tehuelecosaurus Benitezzi – 41 tonnes

Duriatitan specimen – 40 tonnes

Andesaurus Delgadoi – 40 tonnes (7 – 70 tonnes)

21.) Elatitan Illoii – 40 tonnes

22.) Mamenchisaurus Jingyanensis - 40 tonnes

Mamenchisaurus ‘Anyuensis’ – 40 tonnes

Torneria Afrocenia – (10-) 40 tonnes

23.) Lusotitan Atalaiensis – (25 -) 40 tonnes

Cetiosaurus Humeriesticratus – 40 tonnes

Paluxysaurus Jonesi – 39 tonnes

Apatosaurus indet – 39 tonnes

Phuwiangosaurus Sirinohornae – 38 tonnes

24.) Diplodocus Hallorum – 38 tonnes

‘Brachiosuaurs’ Branchai – 37 tonnes

Daxiatitan Binglingli – 37 (-50) tonnes

Rotundchnus Munchehgwnsis – 37 tonnes

25.) Atlantosaurus Montanus – 36 tonnes

26.) Brachiosaurus Nougaredi - 35 tonnes (-100 tonnes)

Lapparentosaurus specimen – 35 tonnes

Unnamed Sauropod – 35 tonnes

‘Mano Espanio’ – 34 tonnes

Uberabatitan Riberio – 33 tonnes

‘Drasilosaura’ – 33 tonnes

Austroposeidon Magnifis – 32 tonnes

Abdrainosaurus Barsbodi - 32 tonnes

Kaijutitan Maui – 32 tonnes

27.) Brachiosaurus Atalaiensis – 31 tonnes

‘Sauropodus’ – 31 tonnes

28.) Janenschia Robusta – 30 tonnes

‘Bananbendersaurus’ – 30 tonnes

Cetiosaurus Conybeari – 30 tonnes

Chuanjesaurus Ananensis – 30 tonnes

Huangetitan Liujiaxensis – 30 tonnes

‘Dongyangosaurus’ – 30 tonnes

Europotitan Eastwoodi – 30 tonnes

29.) Hudiosaurus Sinojapanorum – 30 - 85 tonnes

Pellegrinisaurus Powelli – 30 tonnes

‘Lianonigotitan’ – 30 tonnes

Amphlicoleias Altus – 30 tonnes

Chubutisaurus Insignis – 30 tonnes

30.) Apatosaurus Louisae – 30 tonnes

31.) Gigantosaurus Robustus – 29 tonnes

Mendozasaurus Neguyelap – 28 tonnes

Cedarosaurus Weiskopfae – 28 tonnes

32.) Rebbachisaurus Garasbae – 27 tonnes

‘Blanconcerosaurus’ – 27 tonnes

33.) Huabeisaurus Allocotus – 26 tonnes

34.) Traukotitan Eukodata – 26 tonnes

Quetecsaurus Rusconii – 26 tonnes

Fushanosaurus Quitaieninsis – 26 tonnes

‘Pleurocoleus’ – 25 tonnes

35.) Brontosaurus Exclusus - 25 tonnes

36.) Nullotitan Glaciaris – 25 tonnes

‘Ultrasauros’ Makintoshi – 25 (-200) tonnes

SGP 2006/9 – 25 tonnes

‘Atlantosaurus’ Immanis – 25 tonnes

Xinghesaurus specimen – 25 tonnes

37.) Jiangshanosaurus Lixianensis – 25 tonnes

‘Wintonotitan’ (Austrosaurus) – 25 tonnes

Ferganasaurus Verzilini – 24 tonnes

Apatosaurus Yahnahpin – 24 tonnes

38.) Jobaria Tiguidensis – 24 tonnes

‘Nurosaurus’ – 23 tonnes

39.) Zimbabwe trackmaker Brachiosaur – 23 tonnes

‘Clasmodosaurus’ – 23 tonnes

Indeterminate Antarctosaurus – 23 tonnes

Zigongosaurus Fuxiensis – 22 tonnes

‘Titanosaurus’ Falloti – 21 tonnes

‘Titanosaurus’ Blanfordi – 21 tonnes

‘Brontodiplodocus’ – 21 tonnes

40.) Mamenchisaurus Constructus – 20 tonnes

41.)Mamenchisaurus Hochuanensis – 20 tonnes

Zby Atlanticus – 20 tonnes

42.) Barosaurus specimen – 20 tonnes

43.) Diplodocus Carnegii – 20 tonnes

‘Astrodon’ – 20 tonnes

44.) Austrosaurus Mckillopi – 20 tonnes

‘Biconcavoposeidin’ – 20 tonnes

‘Neosodon’ – 20 tonnes

‘Barrackosaurus’ – 20 tonnes

Atlasaurus Immelaki – 20 tonnes

Saltasaurus specimen – 20 tonnes

‘Brontopodus’ Brachiosaur – 20 tonnes

‘Sauropodnichus’ – 20 tonnes

‘Mohammadisaurus’ – 20 tonnes

Savannasaurus Elliottorum – 20 tonnes

45.) Jainosaurus Sepententrionalis – 20 tonnes

References[edit]

- ^ Rensberger, J. M.; Martínez, R. N. (2015). "Bone Cells in Birds Show Exceptional Surface Area, a Characteristic Tracing Back to Saurischian Dinosaurs of the Late Triassic". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0119083. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1019083R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119083. PMC 4382344. PMID 25830561.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2010). Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- ^ Strauss, Bob."Why Were Dinosaurs So Big? The Facts and Theories Behind Dinosaur Gigantism". About Education. http://dinosaurs.about.com/od/dinosaurevolution/a/bigdinos.htm Archived 2014-10-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sereno PC (1999). "The evolution of dinosaurs". Science. 284 (5423): 2137–2147. doi:10.1126/science.284.5423.2137. PMID 10381873.

- ^ Farlow JA (1993). "On the rareness of big, fierce animals: speculations about the body sizes, population densities, and geographic ranges of predatory mammals and large, carnivorous dinosaurs". In Dodson, Peter; Gingerich, Philip (eds.). Functional Morphology and Evolution. American Journal of Science, Special Volume. Vol. 293-A. pp. 167–199.

- ^ Peczkis, J. (1994). "Implications of body-mass estimates for dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 14 (4): 520–33. doi:10.1080/02724634.1995.10011575.

- ^ "Anatomy and evolution". National Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 2007-11-11. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ Larramendi, A. (2016). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-24.

- ^ Sander, P. Martin; Christian, Andreas; Clauss, Marcus; Fechner, Regina; Gee, Carole T.; Griebeler, Eva-Maria; Gunga, Hanns-Christian; Hummel, Jürgen; Mallison, Heinrich; et al. (2011). "Biology of the sauropod dinosaurs: the evolution of gigantism". Biological Reviews. 86 (1): 117–155. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00137.x. PMC 3045712. PMID 21251189.

- ^ a b Carpenter, K. (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus." In Foster, J.R. and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2006, Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36: 131–138.

- ^ Colbert, Edwin Harris (1971). Men and dinosaurs: the search in field and laboratory. Harmondsworth [Eng.]: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-021288-4.

- ^ Mazzetta, G.V.; et al. (2004). "Giants and Bizarres: Body Size of Some Southern South American Cretaceous Dinosaurs". Historical Biology. 16 (2–4): 1–13. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.1650. doi:10.1080/08912960410001715132.

- ^ Janensch, W. (1950). "The Skeleton Reconstruction of Brachiosaurus brancai": 97–103.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The World of Dinosaurs". Museum für Naturkunde. Archived from the original on 2018-11-16. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ Lucas, H.; Hecket, H. (2004). "Reappraisal of Seismosaurus, a Late Jurassic Sauropod". Proceeding, Annual Meeting of the Society of Paleontology. 36 (5): 422.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

noto2016was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

plosone_titanswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

G.S.Paul2010was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

LHW07was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Morgan, James (2014-05-17). "'Biggest dinosaur ever' discovered". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2017-02-18. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ^ "Giant dinosaur slims down a bit. BBC News Science & Environment". BBC News. 10 August 2017. Archived from the original on 2018-07-17. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- ^ "Don't believe the hype: Patagotitan was not bigger than Argentinosaurus". Sauropod Vertebra Picture of the Week. 2017-08-09. Archived from the original on 2019-04-14. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- ^ Therrien, F.; Henderson, D. M. (2007). "My theropod is bigger than yours...or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 108–115. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[108:MTIBTY]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ "See what African Wildlife Foundation is doing to protect these iconic flightless birds". 2013-02-25. Archived from the original on 2015-04-29. Retrieved 2015-04-18.

- ^ Xu, X., Zhao, Q., Norell, M., Sullivan, C., Hone, D., Erickson, G., Wang, X., Han, F. and Guo, Y. (2009). "A new feathered maniraptoran dinosaur fossil that fills a morphological gap in avian origin." Chinese Science Bulletin, 6 pages, accepted November 15, 2008.

- ^ Pascal Godefroit; Andrea Cau; Hu Dong-Yu; François Escuillié; Wu Wenhao; Gareth Dyke (2013). "A Jurassic avialan dinosaur from China resolves the early phylogenetic history of birds". Nature. 498 (7454): 359–62. Bibcode:2013Natur.498..359G. doi:10.1038/nature12168. PMID 23719374.

- ^ Which was the smallest dinosaur? Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Royal Tyrrell Museum. Last accessed 2008-05-23.

- ^ Conservation International (Content Partner); Mark McGinley (Topic Editor). 2008. "Biological diversity in the Caribbean Islands." In: Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. Cutler J. Cleveland (Washington, D.C.: Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment). [First published in the Encyclopedia of Earth May 3, 2007; Last revised August 22, 2008; Retrieved November 9, 2009]. <http://www.eoearth.org/article/Biological_diversity_in_the_Caribbean_Islands Archived 2013-05-23 at the Wayback Machine>

- ^ Borenstein, Seth (July 31, 2014). "Study traces dinosaur evolution into early birds". AP News. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- ^ Zoe Gough (31 July 2014). "Dinosaurs 'shrank' regularly to become birds". BBC. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Rastrilladas de icnitas terópodas gigantes del Jurásico Superior (Sinclinal de Iouaridène, Marruecos)".

- ^ Boutakiout, Mohamed; Hadri, Majid; Nouri, Jaouad; Diaz-Martinez, Ignacio; Perez-Lorente, Felix (2009). "Rastrilladas de icnitas teropodas gigantes del JuraSico superior (sinclinal de Iouaridene, Marruecos)". Revista Española de Paleontología. 24 (1): 31–46.

- ^ Ibrahim, Nizar; Sereno, Paul C.; Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Maganuco, Simone; Fabri, Matteo; Martill, David M.; Zouhri, Samir; Myhrvold, Nathan; Lurino, Dawid A. (2014). "Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur". Science. 345 (6204): 1613–6. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1613I. doi:10.1126/science.1258750. PMID 25213375. Supplementary Information Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Paleontology News: Spinosaurus Wasn't The Biggest Spinosaur - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs 2nd Edition. United States of America: Princeton University Press. pp. 70–348. ISBN 978-0-691-16766-4.

- ^ Coria, R. A.; Currie, P. J. (2006). "A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina" (PDF). Geodiversitas. 28 (1): 71–118. ISSN 1280-9659. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-26.

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R., Jr.; Rey, Luis V. (2007). Dinosaurs: the most complete, up-to-date encyclopedia for dinosaur lovers of all ages. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ^ Therrien, F.; Henderson, D. M. (2007). "My theropod is bigger than yours...or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (1): 108–115. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[108:MTIBTY]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b https://images-wixmp-ed30a86b8c4ca887773594c2.wixmp.com/f/c4045bc8-87ce-4c02-96c6-0cda7e3e652d/d9j3w9j-11606052-55c1-4e15-8bcd-97790b5977ac.png?token=eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLCJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiJ9.eyJzdWIiOiJ1cm46YXBwOiIsImlzcyI6InVybjphcHA6Iiwib2JqIjpbW3sicGF0aCI6IlwvZlwvYzQwNDViYzgtODdjZS00YzAyLTk2YzYtMGNkYTdlM2U2NTJkXC9kOWozdzlqLTExNjA2MDUyLTU1YzEtNGUxNS04YmNkLTk3NzkwYjU5NzdhYy5wbmcifV1dLCJhdWQiOlsidXJuOnNlcnZpY2U6ZmlsZS5kb3dubG9hZCJdfQ.D84-iKj4Q4GxgCIlR342PtxwASk6OdWWAXfBfOZthRA

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2017-12-31). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-8314-1.

- ^ Sue Tyrannosaurus Rex

- ^ The largest European theropod dinosaurs: remains of a gigantic megalosaurid and giant theropod tracks from the Kimmeridgian of Asturias, Spain, Oliver W.M. Rauhut1,2,3, Laura Piñuela4, Diego Castanera1,2, José-Carlos García-Ramos4, Irene Sánchez Cela4 Published July 5, 2018PubMed 30002951

- ^ "And the Largest Theropod Is..." dml.cmnh.org. Retrieved 2020-02-02.

- ^ a b c "Huge dinosaurs you've never heard of | DinoAnimals.com". dinoanimals.com. 2018-07-16. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- ^ Kellner, Alexander W. A.; Azevedo, Sergio A. K.; Machado, Elaine B.; Carvalho, Luciana B.; Henriques, Deise D. R. (2011). "A new dinosaur (Theropoda, Spinosauridae) from the Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Alcântara Formation, Cajual Island, Brazil" (PDF). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 83 (1): 99–108. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652011000100006. ISSN 0001-3765. PMID 21437377.

- ^ Marty, Daniel; Belvedere, Matteo; Razzolini, Novella L.; Lockley, Martin G.; Paratte, Géraldine; Cattin, Marielle; Lovis, Christel; Meyer, Christian A. (2017-06-20). "The tracks of giant theropods (Jurabrontes curtedulensisichnogen. & ichnosp. nov.) from the Late Jurassic of NW Switzerland: palaeoecological & palaeogeographical implications". Historical Biology. 30 (7): 928–956. doi:10.1080/08912963.2017.1324438. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S.,. The Princeton field guide to dinosaurs (2nd edition ed.). Princeton, N.J. ISBN 978-1-4008-8314-1. OCLC 954055249.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Holtz, Thomas R., 1965- (2007). Dinosaurs : the most complete, up-to-date encyclopedia for dinosaur lovers of all ages. Rey, Luis V., (1st ed ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7. OCLC 77486015.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Richmond, Dean R.; Lupia, Richard; Hunt, Tyler C.; Philippe, Marc (2018). "THE FIRST FOSSIL WOODS FROM THE UPPER JURASSIC MORRISON FORMATION OF WESTERN OKLAHOMA". Geological Society of America. doi:10.1130/abs/2018sc-309834.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ @article{article, author = {Mo, Jin-You and Xing, Xu and Palasiatica, Vertebrata}, year = {2015}, month = {01}, pages = {}, title = {Large theropod teeth from the Upper Cretaceous of Jiangxi, southern China}, volume = {53}, journal = {VERTEBRATA PALASIATICA} }

- ^ Williams, Christopher R. (2012-10-01). "Vertical Air Motion Retrieved from Dual-Frequency Profiler Observations". Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology. 29 (10): 1471–1480. doi:10.1175/jtech-d-11-00176.1. ISSN 0739-0572.

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R., 1965- (2007). Dinosaurs : the most complete, up-to-date encyclopedia for dinosaur lovers of all ages. Rey, Luis V., (1st ed ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7. OCLC 77486015.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix

- ^ Zanno, L. E.; Makovicky, P. J. (2013). "Neovenatorid theropods are apex predators in the Late Cretaceous of North America". Nature Communications. 4: 2827. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2827Z. doi:10.1038/ncomms3827. PMID 24264527.

- ^ "siats meekororum - Bing video". www.bing.com. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- ^ Lee, Y.N.; Barsbold, R.; Currie, P.J.; Kobayashi, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Godefroit, P.; Escuillié, F.O.; Chinzorig, T. (2014). "Resolving the long-standing enigmas of a giant ornithomimosaur Deinocheirus mirificus". Nature. 515 (7526): 257–260. Bibcode:2014Natur.515..257L. doi:10.1038/nature13874. PMID 25337880.

- ^ Molina-Pérez; Larramendi (2016). Récords y curiosidades de los dinosaurios Terópodos y otros dinosauromorfos. Barcelona, Spain: Larousse. p. 268.

- ^ Molina-Pérez, Rubén. (2019-06-25). Dinosaur Facts and Figures : The Theropods and Other Dinosauriformes. Larramendi, Asier., Atuchin, Andrey, 1980-, Mazzei, Sante., Connolly, David., Ramírez Cruz, Gonzalo Ángel. Princeton, New Jersey. ISBN 978-0-691-19059-4. OCLC 1090539985.

- ^ Carpenter, Kenneth (2019-01-25). "History and geology of the Cope's Nipple Quarries in Garden Park, Colorado—type locality of giant sauropods in the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation". Geology of the Intermountain West. 6: 31–53. doi:10.31711/giw.v6i0.34. ISSN 2380-7601.

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2008) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages Supplementary Information

- ^ "Paleontology News: All Known Megatheropods - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 2020-07-16.

- ^ Bates, K.T.; Manning, P.L.; Hodgetts, D.; Sellers, W.I. (2009). Beckett, Ronald (ed.). "Estimating Mass Properties of Dinosaurs Using Laser Imaging and 3D Computer Modelling". PLOS One. 4 (2): e4532. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4532B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004532. PMC 2639725. PMID 19225569. We therefore suggest 5750–7250 kg represents a plausible maximum body mass range for this specimen of Acrocanthosaurus.

- ^ "kem kem giants deviant art - Bing images". www.bing.com. Retrieved 2020-07-17.

- ^ Cau, Andrea; Dalla Vecchia, Fabio M.; Fabbri, Matteo (2013-03). "A thick-skulled theropod (Dinosauria, Saurischia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco with implications for carcharodontosaurid cranial evolution". Cretaceous Research. 40: 251–260. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2012.09.002.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Maleev, E. A. (1955). translated by F. J. Alcock. "New carnivorous dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia" (PDF). Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR. 104 (5): 779–783.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Paul1997was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Woodruff, C; Foster, JR (2015). "The fragile legacy of Amphicoelias fragillimus (Dinosauria: Sauropoda; Morrison Formation - Latest Jurassic)". PeerJ PrePrints. doi:10.7287/peerj.preprints.838v1.

- ^ Carpenter, Kenneth (2018). "Maraapunisaurus fragillimus, N.G. (formerly Amphicoelias fragillimus), a basal Rebbachisaurid from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Colorado". Geology of the Intermountain West. 5: 227–244. doi:10.31711/giw.v5i0.28. Archived from the original on 2018-10-22. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- ^ Bates, Karl T.; Falkingham, Peter L.; Macaulay, Sophie; Brassey, Charlotte; Maidment, Susannah C.R. (2015). "Downsizing a giant: re-evaluating Dreadnoughtus body mass". Biol Lett. 11 (6): 20150215. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0215. PMC 4528471. PMID 26063751.

External & Wikipedia Links[edit]

References for Tyrannosaurus Rex