User:Plexus96/sandbox

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (April 2023) |

The Reforms of Bulgarian Orthography are the historical changes to the spelling and writing system of the Bulgarian language. Until the late 19th century, no standard for spelling/grammar had existed, and most writers would spell according to their own understandings. Before 1945, Bulgarian orthography was heavily etymological — multiple letters and spellings could exist for the same sound depending on its original Proto-Slavic pronunciation, a situation similar to that Modern Greek (especially Katharevousa).

Though the Early Cyrillic alphabet was accurate for the spoken language of the time, by the time of Middle Bulgarian it did not reflect spoken language as well. Though some changes were reflected, namely the loss of the weak yers and the gradual erosion of the case system, most of the original orthographic conventions had fossilized. Around that time, writing had started being more commonly used in matters outside of religion, such as in literature and documents.

Bulgarian writing would decrease Second Bulgarian Empire was conquered by the Ottoman Empire. During the early Ottoman rule of Bulgaria, most religious writing would remain in Middle Bulgarian, especially as the language remained commonly used in administration by the Ottoman Empire and the Danubian principalities. However, by the 18th and 19th centuries, it was mostly supplanted by the Church Slavonic language, a language descended from Old Church Slavonic roughly based on dialects in Ukraine. As the Bulgarian National Revival was nearing its apex, the matter of the national language would be at the center. Various heavily etymological orthographies with both Church Slavonic and Old Church Slavonic influences would be introduced, each based on the author's own speech and dialect. As the Principality of Bulgaria was established, a comparatively simpler spelling was made official, still retaining archaic rules and letters. In the 1940s, during the Bulgarian transition to communism, the Bulgarian alphabet would be finally simplified to near-phonemicity: all etymological spellings which did not conform to spoken language were removed. This included the word-final yers, finally removing the last remnant of the law of open syllables nearly a milennium after its loss.

Middle Ages[edit]

Old Bulgarian[edit]

The early Cyrillic and Glagolitic scripts were based on various dialects in Bulgaria and Macedonia, and as such were most accurate to their pronunciations. For example, the letter ѕ/Ⰷ, representing /dz/, had been entirely lost in most Slavic dialects, but remained in those regions. The original Cyrillic alphabet featured 43 letters (38 if unneeded Greek letters are excluded), but by the 11th century considerable sound change had occured. Most significantly, the Proto-Slavic Yers were starting to be dropped in the weak position (except at the end of the word). Various dialects would begin to merge (mainly in the Rhodopes) or individually denasalize the two nasal vowels, /ɔ̃/ and /ɛ̃/. The main differences would begin to arise during the split between the two major literary centers: Ohrid and Preslav.

The following features were visible in the Eastern (Preslav) dialect:

- Consistent patalisation before front vowels.

- The two yer vowels merge in the strong position: only one of the letters is used (usually ь).

- Common loss of the letter ѕ, especially when as a result of palatalized *g before front vowels (like in ноѕѣ) rather than before *v (like in ѕвѣзда).

- Faster adoption of Cyrillic over Glagolitic.

The following features were visible in the Western (Ohrid) dialect:

- The strong yer vowels always remain distinct, either as their own letter or merged with е or о.

- Confusion of ѧ, ѣ and е.

- Confusion of ѧ and ѫ.

- Conservative use of Glagolitic over Cyrillic.

Middle Bulgarian[edit]

Middle Bulgarian emerged in the 12th century as a literary language in both the Bulgarian Empire and other South and East Slavic lands, where it remained the standard religious language until its replacement by Church Slavonic. It was also the language of administration in the Danubian Principalities and the Ottoman Empire. Its development comprises of the entirety of the Second Bulgarian Empire's existence, as well as the occupation period until it developed into Modern Bulgarian. It did not feature a unified orthographical system, and — similarly to other European languages of the time — scribes would write just according to what they perceived as correct. However, most orthographic conventions from Old Church Slavonic, such as the usage of word-final yers, were retained.

The following features were visible in many various documents and texts from the time period:

- Confusion of ѣ with ꙗ: the old Slavic vowel *ě, first pronounced /æ/, had evolved to an open /ʲa/ in most dialects, contrary to the development in most other Slavic languages. Dialects which today still distinguish the vowel did not confuse the two letters. Depalatalization would lead to the current dual yakavian-ekavian pronunciation in the Eastern dialects and the full ekavism in the Western dialects.

- Denasalization of ѧ and ѫ: the former usually merged with е while the latter either merged with у or remained a distinct oral sound (Modern Bulgarian /ɤ/).

- Mixing of ѧ and ѫ: certain documents use a special letter, ꙛ (capital: Ꙛ), known as the "blended yus", for this united sound. Almost all Bulgarian dialects feature mixing of the nasals to varying degrees. It is most pronounced in the Rhodopean dialects, where they have merged in all locations: мъш, зет vs. мъ̀ш', з'ъ̀т'; мồш', з'ồт', etc. (transcriptions are in the standard dialect notation as used by Stoyko Stoykov). Other dialects, such as most Western dialects, only merge them before soft consonants: (й)езѝк vs. йазѝк. However, most Balkan dialects feature no mixing at all. Standard Bulgarian contains some irregular words (such as жътва) which exhibit mixing.

- Usage of the letters ꙙ and/or ꙝ (known as the "closed little yus") for various purposes: represented a variety of sounds depending on the writer. In some manuscripts, ꙙ replaced ѩ for the iotated sound /jɛ̃/. In texts where ꙙ represented a non-iotated vowel, ꙝ could be used for its iotated equivalent.

The reform of Euthymius of Tarnovo[edit]

Evidence that Euthymius of Tarnovo was attempting to reform the written Bulgarian language in the 14th century can be found in "A letter of commendation to Euthymius" by Gregory Tsamblak and "Stories of the Letters" by Konstantin Kostenechki. Gregory tells that Euthymius took up the task of translating books from Greek into Bulgarian, as he was dissatisfied with the older translations, which were often made by insufficiently prepared people. As they built up, their errors lead to a serious distortion of the sacred texts, to misinterpretation of their meaning and the emergence of heresies. The information is confirmed by the notice that the scribes from Tărnovo had begun to correct the main books for Christianity. In contrast to the writers and translators from the Preslav Literary School, who preferred a free translation, the writers from Tarnovo stuck to the exact transmission of the Greek originals. The written Bulgarian language they imposed was artificial and far from the vernacular. Therefore, it is hard to tell the reform's significance. Dmitry Likhachev defines it as conservative. The rules drawn up by Euthymius applied both to translation and to the creation of original works.

The first grammatical treatise written by Euthymius does not survive, and as such its characteristics are judged by the works of its followers.

National revival[edit]

Inceptions[edit]

By the 19th century, the Middle Bulgarian literary language was almost entirely replaced by Church Slavonic. For a long time, the Cyrillic script was primarily associated with religious texts, and as such was more resistant to changes. However, by the 19th century the Bulgarian sound system had reduced its size, which would necessitate reforms. The Church Slavonic language played an important role in the creation of the modern Bulgarian literary language. Much of the intelligentsia, usually educated in Russia or the West, also preferred Church Slavonic due to its unitary character compared to the various Bulgarian dialects.

Though people like Paisius of Hilendar had spoken of the independence of Bulgarian since the 1760s, its status as a separate language was not well established in European science; indeed, Josef Dobrovský, the father of Slavistics, would write that the South Slavs are only divided by religion and historical states and functionally speak a single, united language which he termed "Illyrian". He divided it into 6 dialects:

- Bulgarian dialect

- Serbian dialect

- Bosnian dialect

- Slovene dialect

- Dalmatian dialect (Chakavian)

- Dubrovnik (Ragusan) dialect

The Bulgarian language was first distinguished from Serbian by Jernej Kopitar, a Slovenian philologist, slavist and balkanist. He would also contribute to the study of the Romanian and Albanian languages. Kopitar was a critic of Dobrovský's model of a unified South Slavic language and suggested that more evidence of Bulgarian be gathered. He took an interest in the language and urged his friend and collegue Vuk Karadžić to write a grammatical treatise on it with the help of a Bulgarian merchant living in Vienna.

Vuk Karadžić's reform[edit]

In his 1822 book "Додатак к Санктпетербургским сравнитељним рјечницима свују језика и наречија, с особитим огледима бугарског језика" ("Addition to the Saint Petersburg comparative dictionary of all languages with a particular overview of the Bulgarian language"), Karadžić translated many folk songs and parts of the Gospels into Bulgarian from Serbian with the help of "A real Bulgarian, born in Razlog" ("Прави бугарин, родом из Разлога"). As his statement suggests, the grammar was based entirely on the Razlog dialect simply because it was the only one he was familiar with. The alphabet was the exact same as the Serbian alphabet with the addition of two other letters - ѐ and ъ.

- The Serbian letter ј was used for the sound /j/. It was also used in the clusters /jɛ/ and /ji/ which are found in neither Standard Bulgarian nor the Razlog dialect.

- The Serbian letters ћ and ђ were included for the sounds /c/ (/kʲ/) and /ɟ/ (/gʲ/) which were common since Middle Bulgarian in most Western Dialects. They are not found in Modern Bulgarian, which is based on the Eastern dialects, but are found in Macedonian as ќ and ѓ.

- The Serbian letters љ and њ were used for the sounds /ʎ/ and /ɲ/. Although they are rare in Standard Bulgarian, the Razlog dialect features them commonly.

- The Serbian letter џ was used instead of дж.

- The letter ѐ was likely pronounced /æ/ (Karadžić, however, described it as "pronounced like French è, which is why it is notated as such", which would instead be /ɛ/) and was used in places where etymological ѣ was located, for example голѐм (the distinct yat is a common feature in all Rup dialects; /æ/ is thought to be its original pronunciation in Old Church Slavonic).

- The modern Razlog dialect does not contain ъ, but the fact that Karadžić included it signifies that he was basing his work off texts that used the letter etymologically. The letter also occured in place vocalised syllabic /l/ (the modern literary language has clusters of ъл and лъ for this: compare съза and сълза).

- The letter щ was replaced by шт.

- The definite articles were written as attached to the word. The masculine definite article was -о

Middle 19th Century[edit]

Fish Primer[edit]

A year later, change came with Petar Beron's Primer with Various Instructions (nicknamed "fish primer" due to the drawing of a whale on the last page). While keeping with many Church Slavic norms, it also introduced the definite articles in writing as a suffix with a hyphen, a major development of the time. While the primer wasn't only focused on grammar, it popularised the idea of using more colloquial language in writing, rather than literary Church Slavonic. Some of its features, such as the sign ӑ, failed to catch on, but remained used by certain authors into the 19th century.

- The word final yers were fully.

- Introduction of a letter for ъ, the sign ӑ. It was only written when stressed - when unstressed, the sound merges with а, so а was written instead (for example, modern трън -> трӑнъ, but трънлив -> транливъ). A similar letter, ѧ̆ (я̆), existed for the sound /jɤ/ found in verb conjugations, like in тарпѧ̆. As they were considered letters with diacritics, they were not part of the alphabet, similarly to й at that time.

- Full retention of the Church Slavonic alphabet — this includes etymological letters (ы, ѣ, ѕ), letters for certain orthographic conventions (і/и, оу/ꙋ, ѧ/ꙗ, ъ, ѿ) and letters for Greek loanwords (ѡ, ѯ, ѱ, ѳ, ѵ).

- Definite articles are used in writing and suffixed with a hyphen.

- Usage of ѧ in places with etymological *ę.

- The letter џ was used for the sound /dʒ/.

- Church Slavonic stress and breathing diacritics were retained.

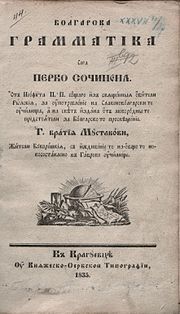

Neofit Rilski's Bulgarian Grammar[edit]

The first true Bulgarian grammar was the "Болгарска грамматїка" (Modern Bulgarian: Българска граматика) by Neofit Rilski. It was published in 1835 in Kragujevac was the first "Slavo-Bulgarian" grammar. As per the name, it based on both colloquial Bulgarian and on Church Slavonic. The stated goal of this was to avoid the problem of the many differing dialects by using the neutral and widespread Church Slavic as a basis.

- The sound ъ is not found at all and is replaced by the CS е, о, у. In certain commonly used words and positions, however, all of them could be written as а.

- The definite article is retained, but written attached to the word. Following the principle of dialect neutrality, the article in Rilski's grammar also has three variations in masculine words, each being of a separate dialect and assigned a separate case form: -о in the nominative case, -атъ (modern -ът) in the accusative case and -а in the genitve case. This construction is not seen in any dialect and is purely artificial, however Rilski argues that using only one of the articles (-o being found in Western and Moesian dialects, -атъ being found in Torlakian dialects and some isolated Eastern dialects and -а being found in the majority of Eastern dialects) would be biased. This practice, while rarely referred to as a "case", is inherited in modern Bulgarian without -o (-ът is in the nominative case and -а is in the accusative case).

- The alphabet was based on that of Church Slavonic, but without letters that existed only for loanwords (other than the well-established ф and ѳ). As such, etymological letters like ѣ and ы were kept, and word-final yers were retained.

Ivan Bogorov's reform[edit]

In 1844, a book titled titled the "first Bulgarian grammar" ("Пѫрвичка бѫлгарска грамматика") was written by Ivan Bogorov. Rather than being based mostly on Church Slavonic, the grammar was based mostly on spoken Bulgarian, particularly around the Tărnovo dialects. Despite its more radical character for its time, the book itself continued to use the traditional Church Slavonic typeface rather than the Russian (Civil) one. The reform started a new wave of Bulgarian grammars based on eastern dialects - several were released within just months of each other, and most of the Church Slavonic traditions were gradually abandoned. Another main feature of the grammar was the systemic Bulgarisation of most Church Slavonic loans, as if evolved from Old Church Slavonic - take перви, which was changed to пѫрви (Modern: първи) due to its etymology as *prьvъ. Greek and Turkish words were also phased out for Bulgarian equivalents, and while some regarded Bogorov's attempts as humorous and idealistic, he mostly succeeded, and many of the words are now inseperable parts of the modern language. After his grammar, Bogorov continued his anti-loanword efforts.

- Like Beron, Bogorov introduces a character for ъ — this time, the Old Church Slavonic letter ѫ, formerly pronounced as a nasal vowel /ɔ̃/ but having since evolved into /ɤ/. Differing from the fish primer, the letter was used when unstressed too — compare трӑнъ, транливъ to трѫнъ, трѫнливъ.

- The definite articles were written as merged to the word.

- The reform introduced a historical accusative case ending -ѫ for feminine nouns, similar to Russian -у. This revived practice would continue being used for many years but would be phased out in the end of the 19th century.

- Vowels after the postalveolar consonants ж, ш, ч and дж were written in their soft versions (ю, я, ѭ, etc.) rather than their hard ones (у, а, ѫ, etc.).

Late 19th Century[edit]

While Bogorov's grammar was popular, it wasn't used for very long as various others took its place. Eventually, the grammar of the Plovdiv school emerged as the most popular, named after the fact that its codifier - Yoakim Gruev - was teaching in Plovdiv. It was even more traditional and etymological to Old Church Slavonic than Bogorov's, with one of its main features being the restoration of thee letters for ъ other than ѫ: the letters ъ and ь - formerly only used as orthographic devices - were reintroduced as vowels in combination with their traditional functions. In the descendants of the Proto-Slavic clusters *ръ/лъ and *рь/ль, the yers were always written following the consonants, compared to spoken Bulgarian where their position alternated, meaning that, while Bogorov's grammar had Бѫлгарія, пѫрви and мѫжъ, the Plovdiv equivalents were Блъгарія, прьви and мѫжъ. In 1858, the Plovdiv school grammar was codified in the book "A Basis for a Bulgarian Grammar" (Основа за блъгарскѫ грамматикѫ), written by Yoakim Gruev (sometimes stylizing himself as Ј. Груева). The alphabet is included at the beginning of the book, containing multiple peculiarities. It contains what is at the time referred to as the "New Bulgarian Alphabet", including all the Bulgarian letters as well as і, ы, ѣ, ѫ and ѭ. Other than that, it contains the letter ꭡ, a letter for the rare sound /jɛ/. However, due to the fact that most /jɛ/ had changed to /ɛ/ (for example, език vs. Serbian језик), ꭡ was only used in the suffix -нꭡ and in soft plurals such as конꭡ and царꭡ (all of which are е in modern Bulgarian, making the letter fully obsolete). Ф is not included in the alphabet - instead, ф and ѳ (properly pronounced as /θ/ according to Gruev) are shown as "extra-alphabetical" letters for foreign words. Despite being used all throughout the book, й is not mentioned. Another feature is the usage of я for Proto-Slavic *ę, even though the pronunciation in Bulgarian is /ɛ/ - this is modelled after Church Slavonic and Russian (for example, modern език vs Gruev языкъ). Definite articles are also, like in Petar Beron's Fish Primer, written as hyphenated suffixes, although two unsuffixed articles remained: -ый is used for masculine adjectives (for example добъръ ("good") becomes добрый ("the good") rather than добри-ятъ) and -а for masculine nouns in the Accusative case. As another feature of the reform, the plural definite article is changed from -тѣ to -ти and -ты, as in the Subbalkan dialect (for example, човѣкъ -> човѣци-ти, майкы -> майкы-ты).

In the end, while the Plovdiv school prevailed for a time due to lack of competition and Yoakim Gruev's position, it was difficult to learn and very far removed from real pronunciation. As such, in the late 1860s, the Tărnovo school established itself - it was much more moderate than the Plovdiv school and was codified in Ivan Momchilov's "Grammar for the New Bulgarian Language" (Грамматика за новобългарскыя езык). While still being very etymologically based (for example with its retention of three signs for /ɤ/, and the inclusion of і and ы), the reform was much simpler, closer to real pronunciation and easier to learn. While the Plovdiv school used a grand total of 37 letters (including й, ф and ѳ), their counterparts in Tărnovo only used 35. They also did not use я for roots coming from Ѧ, instead using е according to the native pronunciation (Plovdiv языкъ vs. Tărnovo езыкъ vs. Modern език). In Momchilov's reform, Rilski's system of three masculine definite articles is partially restored (with the Western Bulgarian -o being thrown out). Articles are written as pure suffixes like in Bogorov's and similar to the neighboring Romanian and Albanian languages who were also starting to codify their orthographies at the time. The article -тѣ is brought back, while -ый is removed and replaced by -ыятъ and -ыя – -ый, is not a definite article found in any dialect, but an artificial construct, likely used simply due to sounding/looking better to its creator, Ivan Bogorov. Some accusative personal and reflexive pronouns are written with an -а ending like in eastern dialects (due to vowel reduction). Modern Bulgarian uses the Western Bulgarian ending -е instead - for comparison, Modern той ме/те/се е направил vs. Tărnovo той ма/та/са е направилъ ("he has made me/you/himself"). The remnants of the syllabic /r/ and /l/ are written as pronounced: compare Plovdiv глъчка, глъчи, Срьбія, срьбскы to Tărnovo глъчка, гълчи, Сьрбія, срьбскы. Other than the mentioned differences, the two schools are very similar - however, due to its higher closeness to spoken language, the Tărnovo school would surpass the Plovdiv school in usage eventually.

Many proposals would be published in the late 1860s and early 1870s. Already people had been trying more radical reforms, such as Petko Slaveykov who, in his satirical newspaper Гайда, would attempt to write without word-final yers for a period of time. Others were that of Nikola Părvanov, a student of Đuro Daničić. Inspired by the Serbian language, he added the letter і for the sound /j/, also removing the letters ю, я, ѭ and щ and replacing them with іу, іа, іѫ and шт where they occured (іуноша, словіа, паіѫжина, ношт), although in some cases the combination ьу was used as well, such as in льубов. The three letters for ъ, as well as ѣ, were kept, and the Serbian letter џ was added (replacing the digraph дж). As another borrowing from Serbian, assimilation is written: Modern Bulgarian сватба, община vs. Serbian and Părvanov Bulgarian свадба, општина. Parts of Părvanov's native dialect are also included, such as the iotated vowels іе and іи; compare modern език, кои vs Părvanov іезик, коіи (language, plural who). Being too radical for its time (and importantly, being very serbified), this orthography was left with no followers.

In the autumn of 1869, the newspaper Свобода ("Freedom") was started in Bucharest by the ambitious Lyuben Karavelov. He would immediately begin writing in his own orthography. In the small article За езикътъ ("About the Language"), he directly states his desire to change the written language to reflect pronunciation; in his words: "We have to understand that language is the mother of grammar, not the other way around: grammar is the history and law of language, and because of that it should be created according to the features and spirit of the language, not on the whim of Gerov, Gruev, Momchilov, Bogorov, etc. Whoever wants to write a grammar for the Bulgarian language should use the living language that is spoken today in Bulgaria, not make his own rules up". Karavelov called out several other language reformers for things such as the inclusion of three letters for /i/ and the anachronistic introduction of two other signs for /ɤ/ (those being ъ and ь). His spelling was characterised by going against previously established practices that were, in his eyes, outdated (although certain literary norms such as word-final yers and the letter ѣ were undisturbed). A major part was the almost full removal of the phonetic properties of yers, whose only purpose with him, other than in definite articles (where they were retained: for example, пѫтьтъ човѣкътъ), was to be silent at the end of words that end in consonants. When found as vowels, they were both replaced by ѫ, (львъ, сънъ vs. лѫвъ, сѫнъ) while ь was replaced by й when found as a consonant (синьо vs. синйо). The artificial definite articles -а and -ый are removed, leaving only -ътъ and -иятъ.Karavelov gets rid of both ы and і, two letters pronounced the exact same way as и, a major point in his original article. Importantly, he was one of the first people to do so with notable success. Another major innovation of Karavelov is the removal of yuses from verb conjugations, where they are instead replaced by а and я, consequently removing the letter ѭ. Other than that, verb conjugations are always hard: compare modern търпя̀, Bogorov тѫрпѭ̀ and Karavelov тѫрпа̀. Notably, this graphical change has not affected pronunciation; the correct pronunciation of the word чета ([I] read) is still /t͡ʃɛˈtɤ/. This orthography would see use in Bulgaria, but it would be especially popular among emigrant writers in Romania and beyond. Some of its innovations, such as the removal of yus conjugations and the single letter for /i/, were entirely new and are still reflected in modern Bulgarian orthography.

In 1869, the Bulgarian Literary Society (the predecessor to the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences) was founded in the Romanian city of Brăila. A year after its creation, the society would create the "Periodic Magazine" (Bulgarian: Периодично списание), and it was in its first edition where Marin Drinov would publish his famous article "За новобългарското азбуке" (meaning literally "About the New Bulgarian Alphabet", although note the strange usage of азбуке compared to correct азбука). This orthography was more conservative than that of Karavelov, but certainly less than its Tărnovo and Plovdiv predecessors. There isn't one single letter for modern ъ, although Drinov removed the usage of ь as a vowel and replaced it with ъ, bringing the letters for /ɤ/ down to two (Momchilov глъчка, пьрви, мѫжъ vs. Drinov глъчка, първи, мѫжъ). Interestingly, he argues for including ѫ by incorrectly stating that it is pronounced with a slight difference (in his words, ъ is closer to English /ə/, while ѫ is closer to English /ʌ/). While this belief was mistaken, ѫ was retained regardless. Drinov removed both ы and і for the same reasons as Kravelov. The western and more etymologically correct pronouns ме, те and се were used, rather than the reduced ма, та, са (or even Gruev's мя, тя, ся) used by previous reforms. The partial article -а is removed, but -ий is not replaced with -иятъ. The yus verb endings are retained (четѫ, знаѭ) but soft endings in words such as правя are not used (правѫ rather than правѭ). Drinov replaces the letter щ with the combination шт (for example, modern къща is кѫшта) calling it "useless", however none of his followers would implement this. On the 23rd page, he says that the letters ѕ and ꭡ would ideally be restored, but arguing that it would be hard to do as the two are both forgotten by authors and ambiguous in usage. In the last pages, Drinov says that the letter й should be removed, as it is a foreign (East Slavic) letter that is used only due to Church Slavonic influence, and that using і for the sound, as in Old Bulgarian (Old Church Slavonic), would be more correct. Afterwards however, he decides against getting rid of it, as it had already implanted itself into common usage.

Post-Liberation[edit]

In 1878 a new Bulgarian Principality was founded. For the first 15 years of its life, the orthography question would be up to the individual writer; already some magazines were allowing authors to write with whatever spelling they saw fit. During this time, Marin Drinov's writing system would remain the most used due to being promoted by the Bulgarian Literary Society.

In 1892, Stefan Stambolov's government initiated the resolution of the spelling issue by appointing a commission. Comprising mainly of well-known teachers and philologists, it wrote a new Bulgarian spelling that year. First used in the inaugural edition of the newly launched "Bulgarian Overview" magazine, the commission's orthography was much less traditional (similarly to the reform of Nikola Părvanov), particularly in relation to certain letters, and was a step away from Russian and toward Serbian influence. The political backdrop of Stambolov's anti-Russian policy provided an environment for the development of the orthography. The key features of the spelling following the Liberation included discarding the letter й, as well as the letters я and ю, the former being replaced by і and the latter substituted with combinations іа and іу. The yuses, ѫ and ѭ, were removed, replaced with ъ in word roots and а and іа in verb endings. The soft endings in second conjugation verbs were also reintroduced: Tarnovo съдѫ vs. Zhivkov съдіа vs. Modern съдя ("(I) sow"). The letter ѣ was preserved with the value of /ja/ and used only where pronounced as such, as seen in words like голѣм, and was replaced with e when pronounced as /ɛ/. ъ and ь were omitted at the end of words, with the letter ь completely removed from the alphabet as і was used in all places where it would be used as a consonant (синьо vs. синіо). Consistency was established in writing prefixes без-, въз-, из-, раз- with a final -з, regardless of pronunciation, contrasting with Russian and Church Slavonic norms (for example: изток vs. исток). Finally, the practice of using double consonants in foreign words was abolished, and the letter щ was introduced in foreign words (earlier orthographies would write шт instead, so Darmstadt would be Дармштат instead of current Дармщат). While the reform never became particularly popular and was abandoned after the fall of Stambolov, a lot of its more pragmatic innovations have been retained, for example not writing assimilation, not writing doubled consonants and using the letter щ in foreign words.

In 1895, Konstantin Velichkov, the Minister of Enlightenment, would similarly assign a commission on the orthography. It included both the members of the previous one and some of their vocal opponents. In the end, the commission came up with a more conservative reform, yet still radical for its time. It only differed from Modern Bulgarian in its treatment of the word-final yers, which it retained: otherwise, it was entirely the same, barring some small changes such as the lack of the partial article and the usage of -нье instead of -не. Both ѫ and ѣ were removed and written according to pronunciation.

In 1898, the minister of enlightenment was Ivan Vazov, and he too would attempt to reform the Bulgarian spelling. His reforms were even less radical than Velichkov's, seeing how they had failed. He retained everything from the Drinov reform, but reinstated the partial article -а for the accusative case. He also changed the old ending -нье to -не. This reform would fail to catch on simply because Vazov would resign before it could be implemented. The new minister, Todor Ivanchov, would immediately start addressing the spelling. His new orthography would be the same as Vazov's, but the letters ѫ and ѭ were removed from verb conjugations and replaced by а and я (the letter ѭ itself was fully removed, as verb conjugations are the only place where it was used). Being a mixture of traditional spelling and practical reform, this orthography would become widely accepted. It would go on to be used until 1945.

20th Century[edit]

In 1923, under the prime ministership of Aleksandar Stamboliyski, Stoyan Omarchevski would form another commission on reforming the Bulgarian spelling. He wanted to simplify the spelling so that, in his eyes, people and learners would have an easier time. The reform was:

- The removal of the ъ and ь from the alphabet. They are removed at the end of words and replaced with another letter otherwise.

- The sound ъ is represented by the letter ѫ, regardless of the origin (мѫка (from мѫка), мѫх (from мъхъ), пѫрво (from пьрво)).

- The letter ѣ is abolished and replaced by я or е depending on its pronunciation (голям, големи).

- The letter ь in the definite article -ьт is replaced by я (конят, денят).

- The ь as a letter representing softness is replaced by й (синйо, актйор).

- The full & partial definite articles become not grammatical, but phonetic. The full article is used when the word afterwards begins with a vowel, while the partial article is used when it begins with a consonant.

This spelling would not be seen well by the more conservative, who saw it as destroying symbols of "bulgarianness". However the reform would remain popular among communists and agrarians.

The orthography would, in the end, last only two years, because after Stamboliyski's murder, it would be repealed. Several parts of it were, however, kept, such as the removal of the vowel ь and its replacement by ъ and я. The spelling would remain used by communists, which led to it being banned in 1928.

The last spelling reform would happen in 1945. The new communist government, the Fatherland Front ("Отечествен фронт"), would create a new spelling, less radical than the one of Omarchevski. The reform would be:

- The full and partial articles are fully retained as in the orthography of Ivanchov (this was not popular among the people making the reforms, but it was still retained).

- The letter ѫ is abolished and replaced by ъ in all cases, except for the word сѫ ("са", meaning "(they) are"), where it is replaced by а instead.

- The letter ѣ is abolished and replaced by я and e according to pronunciation.

- The ъ at the end of words is abolished, where it makes no sound.

- The ь at the end of words is abolished, but the letter is retained for softness before the letter о.

The orthography was published in 1945 by the regency council, and the old orthography was deemed illegal. The reform was executed in 6 months, but its implementation continued for over 20 years.

Today[edit]

The usage of the old orthography is exceedingly rare in the modern day. It is used mostly by pre-1945 immigrant communities and Bulgarian nationalist circles in a similar way to the Belarusian Taraškievica. Certain newspapers and publications also use it, possibly as a political statement.

Similarly to Russian, the old spelling is commonly used to evoke an "archaic" feeling. As the reform was less than 80 years ago, it is remembered much more than the Russian one.

Examples[edit]

| Orthography | Big Yus (*ǫ) | Little Yus (*ę) | Back Yer (*ъ) | Front Yer (*ь) | Syllabic consonants (*rъ, *rь, *lъ, *lь) | Yat (*ě) | Word-final yers | Definite articles | і | Yery (*y) | Postalveolars (*š, *ž, *č) | Plural definite article |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-1945 (Current) | ъ normally, а/я in conj. | Always е | Always ъ | ъC or Cъ depending on position | е and я depending on position | Entirely avoided | Conjoined | Unused | Always hard | Always -те | ||

| 1921-1923

(Omarchevski) |

ѫ normally, а/я in conj. | Always ѫ | ѫC or Cѫ depending on position | |||||||||

| Pencho Slaveykov | ъ normally, а/я in conj., (ѫ/ѭ when stressed conj.) | Always ъ | ъC or Cъ depending on position | Entirely retained | ||||||||

| 1899-1945 (Ivanchov) | ѫ normally, а/я in conj. | Always ѣ | Always -тѣ | |||||||||

| Ivan Vazov | Always ѫ/ѭ | |||||||||||

| Nayden Gerov | Always я (modern /ja/ is ꙗ) | Always ъ | Always ь | Always Съ or Cь | Hyphenated | Unused | Used under the archaic form ꙑ | Always soft | -ти for masculine, -тꙑ for feminine (and masc. accusative) | |||

| Konstantin Velichkov | ъ normally, а/я in conj. | Always е | Always ъ | ъC or Cъ depending on position | е and я depending on position | Conjoined | Unused | Always hard | Always -те | |||

| Stambolov's commission | ъ normally, а/іа in conj. | Written ѣ when pronounced /ja/, е otherwise | Entirely avoided | Used for the sound

/j/ |

Unused | |||||||

| Nikola Părvanov | Always е (ꭡ or іе at the beginning of the word) | Always ъ | Always ь | ъC, ьС or Cъ, Cь depending on position | Always ѣ | Only ь retained | Hyphenated | Always -тѣ | ||||

| 1870-1899 (Drinov) | Always ѫ/ѭ | Always е | Always ъ | ъC or Cъ depending on position | Entirely retained | Conjoined | Unused | |||||

| Lyuben Karavelov | ѫ normally, а/я in conj. | Always ѫ | ѫC or Cѫ depending on position | |||||||||

| Tărnovo school (Momchilov) | Always ѫ/ѭ | Always ъ | Always ь | ъC, ьС or Cъ, Cь depending on position | Used | |||||||

| Plovdiv school (Gruev) | Always я | Always Съ or Cь | Hyphenated | Always soft | -ти for masculine, -ты for feminine (and masc. accusative) | |||||||

| Parteniy Zografski | Always а/я | е normally, а after soft consonants | Always о | Always е | *l clusters are with е and о while *r clusters are with ъ and ь | Used | Unused | Always hard | Always -тѣ | |||

| Ivan Bogorov | Always ѫ/ѭ | Always я | Always ѫ | ѫC or Cѫ depending on position | Conjoined | Used | Always soft | |||||

| Neofit Rilski | Arbitrarily у or а | я normally, ꙗ at the beginning of the word (like Church Slavonic) | Arbitrarily о or а | Arbitrarily е or а | оC, еС or Cо, Cе depending on position | Separate particle | Always hard | Always -тe | ||||

| Fish Primer (Beron) | Always ӑ/я̆ | Always ӑ | ӑC or Cӑ depending on position | Hyphenated | Always -тѣ | |||||||

| Vuk Karadžić | As pronounced in the Razlog dialect | Always е | *l clusters are vocalised to ъ while *r clusters are syllabic р | Always ѐ | Entirely avoided | Conjoined | Unused | Always -тe | ||||

See also[edit]

- Bulgarian alphabet

- Cyrillic script

- Early Cyrillic alphabet

- Reforms of Russian orthography

- Bulgarian language

- Spelling reform

- Yat - A removed Cyrillic letter.

- Yus - A series of removed Cyrillic letters, of which Ѫ and Ѭ were found exclusively in the Bulgarian language.