User:Sheilaevans33/sandbox

Auditory Agnosia

Auditory agnosia, like other forms of agnosia, is a problem of stimulus recognition in a specific sensory modality. It manifests primarily in the inability to recognize or differentiate between sounds, though it covers a "range of impairments in auditory perception, discrimination and recognition” [1]. People with this condition are not deaf, they are able to process basic sensory information, and can physically hear sounds and describe them using unrelated terms, but are unable to recognize them. [2]. Although they can can process pure tones, i.e. single frequencies, most sounds are more complex than this consisting of different acoustic elements, which people with Auditory Agnosia can't categorise because they can't link the auditory information they perceive to meaning [3]. Auditory Agnosia has been reported much less than visual agnosia, and is probably under-reported as many patients diagnosed with the condition "do not complain of an inability to recognize sounds" [4]. It is normally caused by brain injury or illness which disrupts the brain's ability to process what the sound means. Usually, there is damage to the primary auditory cortex (PAC), the cortical region within the temporal lobes of the brain that processes different elements of sound, like rhythm and pitch. The PAC is divided into three parts: primary, secondary and tertiary; auditory agnosia is generally believed to be due to damage to the secondary and tertiary association cortices [5]. Recent research suggests that it may be due to a disruption of the "what" pathway in the brain [6].

| Sheilaevans33/sandbox |

|---|

Symptoms[edit]

Some individuals with Auditory Agnosia have problems with understanding speech - Verbal Auditory Agnosia; others have problems with understanding environmental (non speech) sounds Non Verbal Auditory Agnosia. Individuals with problems understanding speech have sometimes described it as "muffled" or "like a distant foreign language"(p. 216) [7]. Individuals with Non Verbal Agnosia are unable to identify environmental sounds, e.g. they may describe the sound of a car starting as resembling a lion roaring because they they can't associate the sound with "car" or "engine", though they know it isn't a lion creating the noise [8]. Generally, people with Verbal Auditory Agnosia do not have a problem with comprehending non-verbal sounds, although occasionally people can experience both (Mixed Auditory Agnosia) [9]. It is also possible for individuals to have problems specifically with understanding music, this is known as Amusia.

Classification[edit]

There are three primary distinctions of Auditory Agnosia that fall into two categories. The first distinction is in the type of sound the sufferer has a problem with (see Types of Auditory Agnosia); the second is linked to the form the processing problem takes (see categories). The type of Auditory Agnosia experienced and the extent of the problem, depends on where exactly in the brain the damage is located and which specific brain functions have been affected [10].

Types of Auditory Agnosia[edit]

Verbal Auditory Agnosia or Pure Word Deafness is the inability to comprehend the meaning of speech, despite being able to hear, speak, read, and write; there is no problem with language processing, but speech sounds "odd" and words are difficult to identify [11]. However, sufferers still understand words using sign language or from reading books and are themselves capable of speech and even of deriving meaning from non-linguistic communication, such as body language [12]. People with this deficit have described speech as "an undifferentiated continuous humming noise with varying rhythm" [13]. Most people with this condition are able to comprehend non-verbal sounds [14].

Non Verbal Auditory Agnosia or Auditory Sound Agnosia is the inability to identify non-verbal (environmental) sounds, which seem "unintelligible" to them, e.g. an airplane roaring overhead would not be understood to be related to the idea of "airplane" — indeed, the person would not even think to look up [15]. Occasionally, individuals can have a problem with identifying both types of sound (Mixed Auditory Agnosia), however those who do experience both types of the condition can still tell if two sounds are the same or if one sound is louder than another [16].

Interpretive Receptive Agnosia or Amusia is the inability to understand music. It covers a broad spectrum: from those with a mere deficit of rhythmic ability (mild dysrhythmia) to those with heavy all-encompassing amusia, including the recently coined "distimbria"; sufferers regard music simply as "noise", often compared to drainpipes or drills or other invasive forms of background noise. Vocal singing can be understood, but is perceived as "an odd tone of voice" [17]. The standard for diagnosing this condition is based on whether an individual with a "normal" intensity of amusia is cortically unable to distinguish pitch changes of less than three semitones [18].

Two different categories[edit]

A further distinction is based on the differing processing problems involved in identifying sounds: problems with perceptual discrimination (Apperceptive problems) or problems of recognition (Associative problems). It should be noted however that this is a broad distinction only, as to an extent there is a problem of auditory perception in nearly all cases [19]. Recent research also supports the idea of processing occurring at different levels [20].

Apperceptive[edit]

This problem is usually linked to damage of the right hemisphere [21] which leads to difficulties with the "perceptual discrimination" of the acoustic elements of sound, e.g rhythm, pitch and loudness, which have to be properly integrated for people to be able to identify the sound.

It tends to cause non-verbal auditory agnosia but can sometimes contribute towards problems with understanding speech, e.g. Wang et al (1982) suggest that some cases of verbal auditory agnosia are actually apperceptive because they are caused by very quick acoustic changes within speech [22], while, Auerbach et al (1982) suggest this is due to problems of "phonemic discrimination" [23]

However, "classic" Verbal Auditory Agnosia is more usually linked to associative-semantic problems.

Associative[edit]

This problem is usually caused by lesions to the left hemisphere, specifically the temporal lobes and Wernicke's area [24]. Individuals with this problem are unable to associate the sound they perceive to the information stored about the sound, i.e. a semantic processing error where the words associated with a particular sound become meaningless [25]. Generally, associative problems are linked to Verbal Auditory Agnosia, particularly in the "pure" form of the condition, however semantic errors can be involved in problems with recognising non verbal sounds.

Ways to test for Auditory Agnosia[edit]

In order to to be diagnosed with auditory agnosia, the individual must only experience a sensory deficit in the auditory modality. It also needs to be verified that their hearing, language processing abilities and general cognitive processes are intact. There are specific tests to help diagnose the condition, however these tests do have their limitations. Bauer and McDonald (2000) have suggested it would be useful to undertake a more comprehensive assessment of auditory functions when testing for the condition [26].

Meaningless Sounds Discrimination Test[edit]

In this test subjects are presented with two consecutive synthetic noises (usually with a two second interval) and asked whether the noises are the same or different. Those with damage to the right hemisphere have significantly lower scores on this test than those of controls and those with left hemisphere damage [27].

Meaningful Sounds Identification Test[edit]

In this test subjects are presented with a natural sound followed by four pictures. The subject is then asked to point to the picture that best represents the sound they just heard. Those with damage to the left hemisphere do significantly poorer on this test than controls and those with right hemisphere damage [28].

Causes[edit]

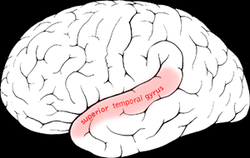

The exact causes of Auditory Agnosia vary, depending on exactly where in the brain the damage is located and the specific functions affected. Often, there is damage to the secondary or tertiary auditory association cortices within the primary auditory cortex (the brain area that processes auditory stimuli), which is located in the bilateral or unilateral temporal lobes of the superior temporal gyrus [29]. The superior temporal gyrus also includes Wernicke's area, which (in most people) is located in the left hemisphere. Localisation and lateralisation of the lesion are significant in determining the extent and form of the condition; often the lesion is disconnecting, though this isn't always the case. Processing problems in auditory agnosia have been found to occur at different levels [30] [31] and can be cortical or sub-cortical, though it is debatable how much is due to higher levels of processing

Neural Correlates of Auditory Agnosia[edit]

Right hemisphere lesions usually cause apperceptive (discriminative) errors in perception [32], whereas left hemisphere damage usually causes associative-semantic errors, e.g. confusing a police whistle with a siren [33]. A case study by Vignola (2003) assessing stroke patients on a music identification task and a test to identify environmental sounds, confirmed the link between apperceptive problems and the right hemisphere, and between associative problems and left hemisphere damage [34].

| Sheilaevans33/sandbox | |

|---|---|

Superior temporal gyrus of the human brain. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | gyrus temporalis superior |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Non-verbal Auditory Agnosia has been associated with either bilateral lesions [35] or right hemisphere lesions [36].

Verbal Auditory Agnosia is linked to either bilateral lesions of the primary and secondary auditory cortices of the superior temporal gyrus (e.g., Coslett, Brashear, and Heilman 1984) [37] or single lesions of the left temporal lobe or temporal isthmus and Wernicke's area [38]. In both sub-types of this condition, it is an "associative" problem which leads to “a dissociation between the intact language cortices in the left perisylvian region and auditory input” [39]. Occasionally damage to the inferior colliculi can cause problems.

Recent Research[edit]

Clarke et al. (2000) studied 4 individuals with left hemisphere damage, to show a dissociation between the location of sound and the recognition of sound, supporting previous research which suggests there are 2 separate processing pathways, and that these abilities are distinct [40].

Functional imaging studies of normal participants has also helped improve understanding of this condition, e,g Lewis et al (2004) examined individuals undertaking a task where they had to identify various types of environmental sounds. Brain activity was examined using BOLD imaging, which highlighted differences in "neural activity" when the sound was recognised and when there was a failure to recognise it. The imaging also illustrated "activity in a distributed network of brain regions previously associated with semantic processing", mainly in the left hemisphere [41].

A more recent study (McLachlan and Wilson 2010) confirmed differences in neural activity in the brain areas responsible for sound localisation and sound identification. They suggest that LTM (long term memory) is significant in enabling individuals to categorise sounds into a "discrete classes", while the "spatial encoding" that is needed to link the various acoustic features of sound takes place in auditory STM (short term memory). This reinforces previous findings of the role of separate "what" and "where" pathways involved in comprehending sound [42], but suggests also that the "underlying neural mechanisms" involved in these processes are "qualitatively different" [43]

Further Research Required[edit]

More research is needed in the area of auditory recognition, as unlike visual recognition there is still no comprehensive theory. According to Bauer and McDonald (2000) there needs to be more research into "category-specificity" and "researchers need to devise more comprehensive and theoretically driven assessments of auditory function"(p. 269) [44]

Special Cases[edit]

A seventy-four year old man named "M" had a special case of auditory agnosia. "M" suffered from, "unilateral left posterior temporal and parietal damage", (Saygin, Leech, & Dick, 2010, p. 107) including Wernicke's Area. These areas of the brain are associated with language processing. He had a stroke when he was 62 and went through intensive speech therapy for twelve weeks to help him recover. He was able to regain his language capacity, but when tested at age 74, he had great difficulty in recognizing non-verbal environmental sounds. He did not have either verbal comprehension deficits nor peripheral hearing problems (p. 107). His condition was very rare because auditory agnosia for non-verbal sounds is usually associated with the right side of the brain. "M" was able to identify familiar Christmas songs and some animal sounds. When he heard music, he couldn't distinguish individual instruments or voices, but he knew it was music. fMRI scans show that after the stroke, his brain re-wired itself through neuronal compensation to account for the damage [45].

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Baer and McDonald (2000) Auditory Agnosia and Amusia, in Feinberg, T. and Farah, M. (Eds): 'Behavioural Neurology and Neuropshychology McGraw-Hill, 2003, pp 257. ISBN 0-07-137432-9

- ^ Martin, N. (2006). Human neuropsychology (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-197452-1, ISBN 978-0-13-197452-4

- ^ Banish, M. T. (2004). Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropsychology (2nd ed.)Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 216. ISBN 0-618-12210-9

- ^ Clarke S., Bellmanm A., Meuli R., Assal G., Steck A. Auditory agnosia and auditory spatial deficits following left hemispheric lesions: Evidence for distinct processing pathways. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38:797–807. [PubMed]

- ^ Ingram, J. C. L. (2007). Neurolinguistics: An introduction to spoken language processing and its disorders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 160–171

- ^ Sternberg, R. J. (2009). Cognitive psychology. Wadsworth Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-50629-4.

- ^ Banish, M. T. (2004). Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropsychology (2nd ed.)Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp 216. ISBN 0-618-12210-9

- ^ Martin, N. (2006). Human neuropsychology (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-197452-1, ISBN 978-0-13-197452-4

- ^ Baer and McDonald (2000) Auditory Agnosia and Amusia, in Feinberg, T. and Farah, M. (Eds): 'Behavioural Neurology and Neuropshychology McGraw-Hill, 2003, pp 257-270. ISBN 0-07-137432-9

- ^ Banish, M. T. (2004). Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropsychology (2nd ed.)Boston: Houghton Mifflin.pp 215-217. ISBN 0-618-12210-9

- ^ Klein et al (1995) Electrophysiological manifestation of impaired temporal lobe auditory processing in verbal auditory agnosia. Brain Language, 51 (383-405)

- ^ Sacs, O (1985). The man who mistook his wife for a hat. New York: Summit books. ISBN 978-0-67-155471

- ^ Banish, M. T. (2004). Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropsychology (2nd ed.)Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 216. ISBN 0-618-12210-9

- ^ Baer and McDonald (2000) Auditory Agnosia and Amusia, in Feinberg, T. and Farah, M. (Eds): 'Behavioural Neurology and Neuropshychology McGraw-Hill, 2003, pp 257-270. ISBN 0-07-137432-9

- ^ Heilman, K. M., & Valenstein, E. (2003). Clinical Neuropsychology. U.S.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513367-71

- ^ Butchel, H A (1989) Auditory Agnosia: Apperceptive or Associative Disorder? Brain Language, 37 (12-25)

- ^ `Winn, P. (2001). Dictionary of biological psychology. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13606-7

- ^ . McDonald, C. & Stewart, L. (2008). Uses and functions of music in congenital amusia. Music Perception, 25 (4), 345-355. doi: 10.1525/mp.2008.[11]

- ^ Bauer and McDonald (2000) Auditory Agnosia and Amusia, in Feinberg, T. and Farah, M. (Eds): 'Behavioural Neurology and Neuropshychology McGraw-Hill, 2003, pp 257-270. ISBN 0-07-137432-9

- ^ Vignolo L. (2003) Music agnosia and auditory agnosia. Dissociations in stroke patients. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 999:50–57. [PubMed]

- ^ Vignolo, L. A. (1982). "Auditory agnosia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Biological Sciences.Series B[18]

- ^ Wang E, Peach RK, Xu Y, et al (2000): Reception of dynamic acoustic patterns by an individual with unilateral verbal auditory agnosia. Brain Language, 73 (442-445)

- ^ Auerbach S., Allard T., Naeser M., Alexander M., Albert M. Pure word deafness Analysis of a case with bilateral lesions and a defect at the prephonemic level. Brain. 1982;105:271–300. [PubMed].

- ^ Vignolo, L. A. (1982). "Auditory agnosia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Biological Sciences.Series B[18]

- ^ Ingram, J. C. L. (2007). Neurolinguistics: An introduction to spoken language processing and its disorders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Bauer and McDonald (2000) Auditory Agnosia and Amusia, in Feinberg, T. and Farah, M. (Eds): 'Behavioural Neurology and Neuropsychology McGraw-Hill, 2003, pp 257-270. ISBN 0-07-137432-9

- ^ Vignolo, L. A. (1982). "Auditory agnosia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Biological Sciences.Series B [18]

- ^ Vignolo, L. A. (1982). "Auditory agnosia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Biological Sciences.Series B[18]

- ^ Ingram, J. C. L. (2007). Neurolinguistics: An introduction to spoken language processing and its disorders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 160–171.

- ^ Vignolo, L. A. (1982). "Auditory agnosia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Biological Sciences.Series B

- ^ Schnider A., Benson D., Scharre D. Visual agnosia and optic aphasia: Are they anatomically distinct? Cortex. 1994;30:445–57. [PubMed][18]

- ^ Vignolo, L. A. (1982). "Auditory agnosia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Biological Sciences.Series B

- ^ Schnider A., Benson D., Scharre D. Visual agnosia and optic aphasia: Are they anatomically distinct? Cortex. 1994;30:445–57. [PubMed][18]

- ^ /Vignolo L. Music agnosia and auditory agnosia. Dissociations in stroke patients. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;999:50–57. [PubMed]

- ^ Spreen I, Benson AL, Ficham, R (1965). Auditory agnosia without aphasia. Arch Neurol. 13 (84-92)

- ^ Fujii et al (1990) Auditory sound agnoisa without aphasia following a right temporal love lesion. Cortex 26 (263-268)

- ^ Coslett H., Brashear H., Heilman K. Pure word deafness after bilateral primary auditory cortex infarcts. Neurology. 1984;34:347–52. [PubMed]

- ^ Vignolo, L. A. (1982). "Auditory agnosia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Biological Sciences.Series B[18]

- ^ Coslett, H. Auditory Agnosias in Gottfried JA (2011) Neurobiology of Sensation and Reward. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; (section 10.7) 2011

- ^ Clarke S., Bellmanm A., Meuli R., Assal G., Steck A. Auditory agnosia and auditory spatial deficits following left hemispheric lesions: Evidence for distinct processing pathways. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38:797–807. [PubMed]

- ^ Lewis J., et al (2004) Human brain regions involved in recognizing environmental sound in Gottfried JA (2011) Neurobiology of Sensation and Reward. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; (section 10.7)

- ^ Maeder, P (2000) Distinct Pathways Involved in Sound Recognition and Localization: A Human fMRI Study NeuroImage 14, 802–816 (2001) doi:10.1006/nimg.2001.088

- ^ The central role of recognition in auditory perception: A neurobiological model. McLachlan, Neil; Wilson, Sarah (2009) Psychological Review, Vol 117(1), Jan 2010, 175-196. doi: 10.1037/a0018063

- ^ ^ Baer and McDonald (2000) Auditory Agnosia and Amusia, in Feinberg, T. and Farah, M. (Eds): 'Behavioural Neurology and Neuropshychology McGraw-Hill, 2003, pp 257-270. ISBN 0-07-137432-9

- ^ . Saygin, A. P., Leech, R., & Dick, F. (2010). Nonverbal auditory agnosia with lesion to Wernicke's area. Neuropsychologia, 48, 107-113. doi: 10 .1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.08.015

Further reading[edit]

Polster, M. R., & Rose, S. B. (1998). "Disorders of auditory processing: Evidence for modularity in audition". Cortex,. 34 (1): 47–65.

Coslett, H., Auditory Agnosias in Gottfried JA (2011) Neurobiology of Sensation and Reward. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press;section 10.7.

External links[edit]

- Types and brain areas

- Total Recall: Memory Requires More than the Sum of Its Parts Scientific American (accessdate 2007-06-05)

Category:Medical terminology

Category:Neurological disorders