User:Sunny XB/sandbox

Articulatory suppression occurs when a person repeats words, e.g., single word “the”, or a group of words, “mesa, silla, sillon”, after hearing a list of words to be recalled, either sequential recall or free recall. This inhibition of memory activity is mostly noticed among simultaneous interpreters.

Baddeley's Working Memory Model[edit]

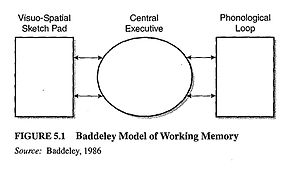

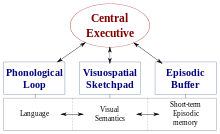

When studying the mechanism of AS effect, it is unavoidable to mention the working memory model that was proposed by Baddeley and Hitch in 1974. [1] This model initially consisted of 3 components, namely, the central executive, and two slave systems, the phonological loop and the visuo-spatial sketchpad. The phonological loop processes sound and phonemes, and can be further broken down into a short-term phonological store and an articulatory rehearsal components. The AS effect is mainly working with phonological loop. Although this original model was proved to be helpful in explaining many phenomena, Baddley improved the model by adding a fourth component, the episodic buffer, into the model. Allowing for temporary retention of integrated information, episodic buffer is believed to connect long-term memory and semantic meaning in working memory. [2]

Articulatory Suppression(AS) and Irrelevant Speech(IS)[edit]

Articulatory suppression has received a huge degree of research efforts. With regard to the relationship with irrelevant speech,AS and IS effect are different, but significantly related.The irrelevant speech effect involves the lowered performance of sequential recall when speech sounds are presented, even under the condition that the list items are presented visually. The speech sounds could be any sounds in participant's native language or foreign language or even a non-language.[3] Disruption cause by AS and IS are similar, but AS effect is twice as large as IS effect, so the magnitude of disruption between AS and IS is more pronounced. [4]

Feature Model and Phonological loop[edit]

From the view of feature model, AS and IS are both adding noise to the memory activities, with even more resources diverted by AS than by IS. This noise added offers a competitive force and impairs the performance in a person's recall task. The feature model can explain the impairment by both AS and IS, and also the irrelevance of the phonological and semantic composition of the IS. Working memory and feature model differs at the phonological similarity of irrelevant speech effect and source items. [5]

AS effect has been used as a media when trying to understand some phenomena. To study the nature of cross-linguistic variation in digit span, researchers examined the data of 6 groups of people whose native language was Chinese, English, Finnish, Greek, Spanish and Swedish. The performance under control conditions showed a better performance of Chinese speakers. However, under AS condition, superiority of Chinese speakers was absent. It is indicated that the prevention of translating visual stimuli into phonological code may contribute to the lower performance of Chinese speakers and therefore, phonological loop is believed to be the key to a superiority of digital span.[6]

The role of Articulatory Suppression[edit]

Articulatory suppression was brought to the attention of Donald Broadbent in 1981. He found that suppression was pronounced with grouping of stimuli, the items in a group were either recalled all or none, not part of a group[7]

One study suggested that a whistle task can also generate the articulatory suppression. Their study was to investigate whether articulation is due to the activation of certain phonological loop or due to the intermittent activity. They did two experiments: one involves recall phonologically similar or dissimilar letters given visually in sequence. There were two conditions: some suppression and no suppression, while in suppression condition, the participants were further grouped into groups of intermittent speech suppression and intermittent whistle suppression; and the other experiment used a similar design but in the suppression condition, the whistle was either an intermittent whistle or a continuous whistle. The points of this difference was that intermittent whistle would interfere the articulatory activity more, while when participants habituated to a continuous whistle, it required a minimum attention. The results shows that the recalling performance of the groups of intermittent whistle is the most impaired, which indicated that the effect of articulatory suppression was due to the intermittent articulatory activity in stead of phonologically irrelevant activity.

As the researcher noticed that articulation is composed of four stages, the preparation to speak, speech programing, the actual articulation of the speech and feedback. Since it is concluded that the intentions to speak, actual articulation and feedback are not the major part, but speech programing is the focus, researchers designed the experiment targeted at this stage.[8]

Articulatory suppression does not necessarily involve articulation. It does not impact on memory coding, but on performance of memory by reducing participant’s capacity to process information. [9]

Articulatory suppression is also believed to play a role in short-term memory by working on immediate false serial recognition of lists of words. The experiment showed that under articulatory suppression, the recall of societal and non-associated words is greatly impaired, resulting in a mismatching, particularly with a lure word.[10] There are evidence that articulatory suppression also deteriorate reproduction of words and verbal estimation of time, while irrelevant speech or other sounds does not affect cognitive timing. Therefore, cognitive timing requires some working memory to hold temporal data by means of phonological loop. This is another piece of evidence that working memory plays an important role in articulatory suppression. [11]

In one experiment, participants were asked to memorize two objects while doing an AS task. The results showed a decrease of the effect of working memory comparing holding one objects in memory or holding three objects in memory but no AS. This experiment demonstrated that AS can reduce working memory guided visual attention, particularly when memory load rises.[12]

Articulatory Suppression in Simultaneous Interpreting[edit]

The effect articulatory suppression is most studied with simultaneous translators. In a study, the influence of AS was assessed on three groups: student of interpreting, professional interpreter and monolingual control group. The participants were asked to recall words and psudo-words in silent condition, standard AS condition ( repeating pa) and complex AS condition (repeating mesa, silla and sillón). The results showed a general AS effect for monolingual and students in silent and standard condition, but not for professional interpreters. However, the complex AS effect, ie, non-word and repeated mesa, silla and sullen, appeared in all three groups regardless of their expertise level. The correct recall was reduced for monolingual controls when they were working on producing irrelevant speech, but the recall of professional interpreters remained the same level regardless of the irrelevant speech. The researcher further discussed the AS effect by the material to be studied, types of articulation and articulatory rate. It was found that the material, being a real word or pseudo-word, did make a difference for monolingual control but not for interpreters or students with interpreting practices. In terms of type of articulation, the results was in compliance with other researches that recall was impaired and complex AS effect had shown for both interpreting students and professional interpreters. The results suggested the load of working memory was increased, and so the capacity has decreased to hold the word in working memory. It is also indicated that long-term memory of semantics played a role here, which might explain why professional interpreter’s performance was not affected by complex AS with words but affected by psudo-words. Another aspect was the articulatory rate. The monolingual control group tended to make more articulations while interpreters and students of interpreting tended to adjust the rate to make more correct recall. This might suggest that they have better control of what to retrieve from long-term memory and thus hold information from the phonological loop to attenuate the articulatory rate. In summary, this study showed that interpreters can decrease the AS effect, partly due to the retrieval of semantics from long-term memory, and partly with practice and experience.[13]

There are evidence showing that the effect of articulatory suppression was dependent on how well the interpreters know the material. Further, if the material was in the native language of interpreters, the effect would disappear. When interpreters do simultaneous Interpretation, the skills to attend to the given language and production in the target language rely on long-term word knowledge, while working memory, rather than linguistic skills, plays a more important role in this activity.[14]

As indicated in Baddeley’s work memory theory, AS prevents recall by disrupting the articulatory loop that people tend to use to remember material. This adverse effect is mostly noticed on simultaneous interpreters. It is often studied on how AS affects working memory, but recently a study has examined if AS affects retention of information as well. The performance of the participants in control condition (no AS) and AS condition and complex AS condition were compared and the results showed that No-AS condition indicated the best performance of free recall of 50 words, and complex AS condition showed the least satisfying performance. The difference between AS and complex AS condition is explained by the fact that to repeat a single word is less effortful than repeating three different words. Researchers went further on investigating the effect on simultaneous interpreting. In this study, one English test, the practicing material for simultaneous interpreting was used. The interpretation was recorded and scored individually. A general finding was that the performance of simultaneous interpreting was positively correlated with AS condition.[15] Moreover, it is suggested that the episodic buffer mediates the AS effect.[2]

Another perspective[edit]

AS is noted as an interference to brain functioning, but this blocking effect was also used to treat insomnia. AS creates low cognitive activity and the arousal is negligible, so it can be used to block undesirable thoughts before the onset of sleep or during nocturnal awakening. The study recruited 30 to 40 insomniacs, which are self-referrals and students who were facing final exams and developed insomnia. The basic methods were to repeat simple small set of phonemes at a reasonable rate to compete with the intrusive thoughts that the participants may otherwise be occupied by. The repeating procedure appeared to be unusually effective since one-third of participants reported improvement shortly after the treatment and more experienced As effect after a few more fine-tuning. For those who did not easily subject to repeated phoneme, researchers suggested them to do a more complex task, such as articulate relative words about a certain category, e.g., Albania, Bermuda, Canada...etc. It was done without too much focus on trying to recall a certain word, therefore did not increase the arousal of participants. Researchers noted that there might be disagreement on whether this complex method was AS, involving articulatory loop and the visuo-spatial sketch pad, but they were sure the reliance of subvocal speech was a form of AS in the sense that it suppressed articulation of undesirable thoughts. These cases appeared to have a positive results. In order to explore the effectiveness of AS, both qualitatively and quantitatively, the researchers particularly studied one case involving a chronic insomnia. The participant’s sleep onset took about 10 to 120 minutes, and sleep maintenance took 15 to 60 minutes if awake nocturnally. The participant went through the four-phase procedure that featured sleep hygiene, muscular relaxation, cognitive control by forward planning and particularly cognitive control by AS. After 9-weeks’ treatment, the results analyzed indicated that there was a gradual improvement over the duration. During the follow-up, the participants reported that forward control were most effective for sleep onset while to resume to sleep, it was the AS that were most effective. The effectiveness of AS for maintenance of sleep was consistent with the result of the 30 to 40 case series. Admittedly, the lack of systematic assessment and follow-up is a limit of this study. Nevertheless, the potential of treating insomnia was generally supported by the study, and it could be used as an alternative for those who are tolerant for medication. Still, it is needed to find out what is the most effective form of AS.[16]

References[edit]

- ^ Baddeley, A. D. (1974). Work Memory. Academic Press.

- ^ a b Baddeley, Alan (1 November 2000). "The episodic buffer: a new component of working memory?". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 4 (11): 417–423. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01538-2. PMID 11058819.

- ^ Hanley, J. Richard (May 1997). "Does Articulatory Suppression Remove the Irrelevant Speech Effect?". Memory. 5 (3). doi:10.1080/096582197388635.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Neath, Ian; Farley, Lisa A.; Surprenant, Aimée M. (1 November 2003). "Directly assessing the relationship between irrelevant speech and articulatory suppression". The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A. 56 (8): 1269–1278. doi:10.1080/02724980244000756. PMID 14578083.

- ^ Neath, Ian (NaN undefined NaN). "Modeling the effects of irrelevant speech on memory". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 7 (3): 403–423. doi:10.3758/BF03214356. PMID 11082850.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Chincotta, Dino; Underwood, Geoffrey (1 March 1997). "Digit Span and Articulatory Suppression: A Cross-linguistic Comparison". European Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 9 (1): 89–96. doi:10.1080/713752545.

- ^ Broadbent, Donald E.; Broadbent, Margaret H. P. (NaN undefined NaN). "Articulatory suppression and the grouping of successive stimuli". Psychological Research. 43 (1): 57–67. doi:10.1007/BF00309638.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Saito, Satoru (1 January 1998). "Phonological loop and intermittent activity: A whistle task as articulatory suppression". Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology/Revue canadienne de psychologie expérimentale. 52 (1): 18–24. doi:10.1037/h0087275.

- ^ Richardson, J.T.E.; Baddeley, A.D. (1 December 1975). "The effect of articulatory suppression in free recall". Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 14 (6): 623–629. doi:10.1016/S0022-5371(75)80049-1.

- ^ Macé, Anne-Laure; Caza, Nicole (1 November 2011). "The role of articulatory suppression in immediate false recognition". Memory. 19 (8): 891–900. doi:10.1080/09658211.2011.613844. PMID 22032514.

- ^ Franssen, Vicky; Vandierendonck, André; Van Hiel, Alain (NaN undefined NaN). "Duration estimation and the phonological loop: Articulatory suppression and irrelevant sounds". Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung. 70 (4): 304–316. doi:10.1007/s00426-005-0217-x. PMID 16001277.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Soto, D.; Humphreys, G. W. (1 July 2008). "Stressing the mind: The effect of cognitive load and articulatory suppression on attentional guidance from working memory". Perception & Psychophysics. 70 (5): 924–934. doi:10.3758/PP.70.5.924. PMID 18613638.

- ^ Yudes, Carolina; MacIzo, Pedro; Bajo, Teresa (NaN undefined NaN). "Coordinating comprehension and production in simultaneous interpreters: Evidence from the Articulatory Suppression Effect". Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 15 (2): 329–339. doi:10.1017/S1366728911000150.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Padilla, Francisca; Bajo, Maria Teresa; MacIzo, Pedro (15 November 2005). "Articulatory suppression in language interpretation: Working memory capacity, dual tasking and word knowledge". Bilingualism. 8 (3): 207–219. doi:10.1017/S1366728905002269.

- ^ Christoffels, Ingrid (1 March 2006). "Listening while talking: The retention of prose under articulatory suppression in relation to simultaneous interpreting". European Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 18 (2): 206–220. doi:10.1080/09541440500162073.

- ^ Levey, A.B.; Aldaz, Jose Antonio; Watts, Fraser N.; Coyle, Kieran (NaN undefined NaN). "Articulatory suppression and the treatment of insomnia". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 29 (1): 85–89. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(09)80010-7. PMID 2012592.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)