Plebiscite of Veneto of 1866

| Plebiscito delle province venete e di quella di Mantova | |

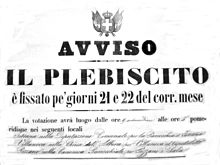

Notice of convocation of plebiscite in the city of Treviso | |

Kingdom of Italy before the plebiscite

Venetian provinces and the province of Mantua

Austrian Empire | |

| Country | |

|---|---|

| Region | Provinces of Veneto and Mantua |

| Date | October 21 and 22, 1866 |

| Type | Plebiscite with universal male suffrage |

| Theme | Annexation to the Kingdom of Italy |

| Outcome | Yes: 99,99% No: 0,01% |

| Turnout | 85% of eligible voters |

The Venetian plebiscite of 1866, also known officially as the Plebiscite of Venetian Provinces and Mantua (Italian: Plebiscito di Venezia, delle province venete e di quella di Mantova), was a plebiscite that took place on Sunday, October 21 and Monday, October 22, 1866 to sanction the annexation to the Kingdom of Italy of the lands ceded to France by the Austrian Empire following the Third War of Independence.

Historical context[edit]

Third Italian War of Independence[edit]

In April 1866, the Kingdom of Italy entered into a military alliance with Prussia, aiming to unite Veneto and Trent to its territory. The alliance was maintained despite the Austrian offer to cede Veneto to Napoleon III's France (Austria officially had no diplomatic relations with Italy), which in turn would hand it over to Italy.[1] The Third War of Independence, unleashed by the Italian side within the larger framework of the Austro-Prussian war, saw, after the initial defeat at the Battle of Custoza that occurred four days after the declaration of war on June 20, military successes by Garibaldi in Trentino, at Bezzecca, and by Cialdini, who reached as far as Palmanova and won the Battle of Versa. The Italian navy's defeat at the Battle of Lissa on July 20 convinced the Kingdom of Italy to accept a truce starting July 25 and begin negotiations that led to the end of hostilities on the Italian-Austrian front with the Armistice of Cormons, signed on August 12.

The July 25 truce froze troop movements and, by that date, the entire remaining territory of the former Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia was liberated from Austrian rule, with the exclusion of only the fortresses of the Quadrilatero: Verona, Legnago, Mantua and Peschiera del Garda, as well as Palmanova and Venice, the latter city characterized by strong unitarian symbolism and the memory of its uprising during the Revolutions of 1848.

Peace of Prague[edit]

Austria, defeated by Prussia (armistice of Nikolsburg), ceded by the Peace of Prague of August 23, 1866, the remaining territories[2] of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia to France, on the understanding that Napoleon III would hand them over to Victor Emmanuel II after organizing a consultation, which formally confirmed the will of the people to the liberation of Veneto from Austrian rule.

The terms of the treaty, as far as the plebiscite was concerned, did not meet with the favor of the king and the Italian government:

The plebiscite is a truly ridiculous act, and it greatly offends the King. [...] What, then, does the Plebiscite become? I am not so persuaded that it is inevitable. What can come of it by not doing it? Austria does not seem to me to be able to bring it in as a condition for evacuating. By now the stipulation between Austria and France has taken effect. We will make a treaty on our own with Austria, and in this treaty we will not talk about the Plebiscite.

— Letter from Prime Minister Bettino Ricasoli to Foreign Minister Emilio Visconti Venosta, September 4, 1866[3]

The Italian newspapers will have informed you by now of the bad impression produced by the Treaty of Cession to France and the mission of General Leboeuf. The very plebiscite that was supposed to be a way of avoiding a retrocession took under the pen of the French government and the Emperor himself the form of a restrictive condition of cession. [...] And note that where the plebiscite project was worst received was precisely in Veneto. [...] Italian troops will soon enter Venice and the other fortresses, and together with the troops Italian authorities will be installed. In this way it will be understood that the handover and redelivery of the fortresses and territories will be accomplished and General Leboeuf's mission will be finished. The plebiscite will take place thereafter simultaneously throughout Veneto, provoked by the Municipalities and as a spontaneous manifestation of the will of the country. In this way after the peace is signed, in three or four days everything would be over, because in Venice and Verona our soldiers would enter and our authorities would be installed. Venice would be ours and the plebiscite would appear as a subsequent formality. [...] If our troops could not enter, except after the plebiscite, into Venice, if General Leboeuf had to remain there as the representative of a sovereignty, call the populations to vote etc., the country, believe it, would be put to too severe a test, the Government would be discredited, and the King would be forced to accept a situation whose consequences would not be so soon erased.

— Letter from Foreign Minister Emilio Visconti Venosta to Costantino Nigra, September 5, 1866[4]

The plebiscite was also opposed by the Venetian Central Committee, which in this regard cited the request of the Venetians in 1848 in favor of a merger with Piedmont of their provinces by staying under the Savoy dynasty,[5] a request renewed when the war ended in 1859.[6][7]

Treaty of Vienna[edit]

The Treaty of Vienna of October 3, 1866, concluded between Austria and Italy, laid down the conditions of the surrender and stated in its preamble that the Emperor of Austria had ceded the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia to the Emperor of the French, who, in turn, had declared himself ready to recognize the reunion of the “Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia to the states of His Majesty the King of Italy, subject to the consent of the duly consulted populations.”[8] Article 14 of the treaty allowed the inhabitants of the region, who so desired, to move with their property to the states that remained under the rule of the Austrian Empire, thus retaining their status as Austrian subjects.[8] The evacuation of the territory ceded by Austria, detailed in Article 5, would begin immediately after the signing of the peace, the date of which would coincide with the day of the exchange of ratifications of the Treaty of Vienna, as stated in the first article of the treaty.[8]

Convocation of the plebiscite[edit]

On the part of the Italian government was presented to Victor Emmanuel II the Report of the President of the Council and the Minister of Grace and Justice and Cults to H.M. the King concerning the plebiscite of the Venetian Provinces: the report began with a preamble stating that the Kingdom of Italy “grew and enlarged with the spontaneous consent of the peoples anxious to give the national idea a form, which would ensure its unfolding, and be to Europe a guaranty of order and civilization”; the events of 1848 and the related manifestations of intentions of union with the Kingdom were then recalled,[9] which were followed by “seventeen years of resistance and suffering.” In response to the report the sovereign issued Royal Decree No. 3236 on Oct. 7 to convene the plebiscite, unbeknownst to the French,[10] published in the Official Gazette only on Oct. 19.[11]

In those days the official handing over of fortresses and cities by the French to local authorities had begun, followed by the entry of Italian troops: Borgoforte on October 8, Peschiera del Garda on October 9,[12] Mantua and Legnago on October 11, Palmanova on the 12th and Verona on the 15th,[13] while Venice was handed over last on October 19.

On October 17, the decree convening the plebiscite was issued and its procedures were announced: voting would take place on October 21 and 22, while ballot counting would take place from the 23rd to the 26th; finally, on the 27th, the court of appeals in Venice, meeting in public session, would add up the data and communicate the results to the Ministry of Justice in Florence (at that time the capital of Italy), and a deputation of notables would leave to take the results to Victor Emmanuel II. At the same time, it was indicated that Venice, Padua, Mantua, Verona, Udine and Treviso would be the seat of military intendencies.[14]

News of the convocation decree, circulated in the press on Oct. 17, provoked the reaction of French plenipotentiary general Edmond Le Bœuf, who protested that “in the face of royal determinations, his handing over of Veneto to three notables so that they might organize a plebiscite becomes derisory [... ] and on the other hand, the Royal Decree being a violation of the treaty, he protested that he was reporting it to his government, and that without further order from the Emperor he would not remit Veneto."[15] Genova Thaon di Revel succeeded in convincing him that these were only preparatory instructions given to the municipalities,[10] causing him to withdraw his protest,[16] but he admitted that ‘he was right after all.’[10]

The October 19 cession[edit]

The Austrian garrison had begun its abandonment of the city of Venice as early as the night of October 18, with the first units embarking on Lloyd Triestino shipping vessels and the rest of the troops gathered, awaiting embarkation, on the Lido.[17]

On the morning of October 19, General Le Bœuf, who was staying at the Europa Hotel, brought together the Austrian military commissar General Karl Möring, Italian General Thaon di Revel, the municipality of Venice, the commission in charge of receiving Veneto, the consul general of France M. de Surville and M. Vicary to carry out the procedures for the handover of power.

The formalities took place in four stages:[18]

- at 7:00 a.m. Möring handed over the fortress of Venice to the French representative Le Bœuf;[10]

- at 7:30 a.m. General Le Bœuf placed the fortress of Venice back in the hands of the city municipality and aldermen Marcantonio Gaspari, Giovanni Pietro Grimani and Antonio Giustiniani Recanati;[19]

- then Möring handed over the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia to the French representative Le Bœuf;

- at 8:00 a.m. General Le Bœuf finally “redelivered” Veneto to Luigi Michiel and Edoardo De Betta, representatives of Venice and Verona, respectively, chosen at the suggestion of Thaon di Revel,[10][20] who signed the redelivery minutes; Achille Emi-Kelder, representative of Mantua, was momentarily absent due to a sudden indisposition, however, and signed the deed of cession later.[21]

The redelivery of Veneto was presented by Le Bœuf with the following statement:

In the name of H. M. the Emperor of the French, ... : We General Le Boeuf having regard to the treaty signed in Vienna on August 24[22] 1866 between the Emperor of the French and the Emperor of Austria about the Veneto: Having regard to the surrender to Us of the Veneto on October 19, 1866 by General Móhring Commissioner of H.M. the Emperor of Austria in the Veneto we declare to return the Veneto to itself so that the populations dispose of their destiny and may freely exercise with Universal suffrage their votes for the annexation of the Veneto to the Kingdom of Italy.[21]

The latter ceremony was originally scheduled to take place in the hall of the Great Council of the Doge's Palace, but - according to Dubarry - Le Bœuf thought it more appropriate to concentrate all the various handovers in a single event and place, in order not to leave long intervals of time between one transfer of power and another.[18]

Immediately after the signing, Michiel had the tricolor raised on the flagpoles of St. Mark's Square, while volleys of artillery rang out and rumbled; later, according to the agreements made, he asked Thaon di Revel to let the Italian troops enter the city. The Italian general, who went to the railway station together with the aldermen, thus welcomed his troops, who paraded through the city divided into three columns, each preceded by a civic band: the first went along the Cannaregio street, the second along the Tolentini street, and the third sailed along the Grand Canal in barges.[23] After crossing the city all in celebration and paved with tricolors, at 3 p.m. the three processions converged on St. Mark's Square in a parade that went on for another two hours.

On the same day, the Oct. 7 decree for the plebiscite was published in the Official Gazette.[10]

"The President of the Council of Ministers received the following dispatch from Venice today at 10 ¾ noon:[24]

The Royal Italian flag waves from the masts of St. Mark's Square, greeted by the frantic shouts of the exultant population. - General Di Revel

The Prime Minister responded immediately with this dispatch:

To the Municipal Representation of Venice - The King's Government salutes Venice as the Italian national flag waves from the flagpoles of St. Mark's Square, a symbol of Venice returned to Italy, and Italy returned at last to itself. - Ricasoli"— Official Gazette, October 19, 1866[11]

According to some sources, Veneto was instead ceded directly from Austria to the Kingdom of Italy on October 19: the newspaper Gazzetta di Venezia reported in very few lines that: “This morning in a room of the Europa Hotel the cession of Veneto was made.”[25]

On October 20 royal commissioner Giuseppe Pasolini, who had already been appointed since October 13, arrived in Venice.[10]

The voting[edit]

Voting for the plebiscite took place on October 21 and 22, 1866; in Venice, the election offices remained open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. on both days.[26]

The plebiscite was held under universal male suffrage. Voting instructions, established by the decree of January 7,[11] were disseminated to the population through posters, as in the case of the city of Mantua:

The population of this City as well as of the others in the Venetian region, is invited to express its will to reunite with the KINGDOM OF ITALY by means of a PLEBISCITE, and in order for this to be accomplished without delay, it is the intention of the KING's Government that the relevant arrangements be made at once.

The vote will take place on the next 21st and 22nd at hours to be determined. The City of Mantua will be divided into six Sections in each of which five Arbitrators will work to ensure the legality of the act.

All Citizens who have reached the age of 21, who have been domiciled for six months in the Municipality and, excluding women, not excluding those who were convicted of crime, theft or fraud, will be eligible to cast their vote. Citizens who were members of the National Army or Volunteers during the campaign for National Independence shall be eligible to vote even if they have not reached the age of 21.

Voting will follow according to the formula set forth below. Bulletins printed to this effect will be distributed at locations to be indicated by other notice. The Citizens will express their will to join the Kingdom of Italy by bringing to the ballot box that will be located in the locality also to be designated either the printed bulletin or another manuscript that is valid for the manifestation of the will.

CITIZENS

Come joyfully to the fulfillment of an act that in the meantime assures an era so longed for and will also demonstrate in a new way that among us there is but a single vow and a single aspiration, our union to the great Italian family under the leadership of the Magnanimous King VICTOR EMMANUEL.

FORMULA

"We declare our union to the Kingdom of Italy under the Constitutional Monarchical Government of King Victor Emmanuel II and his successors."

— Manifesto of the Municipality of Mantua, October 18, 1866

It was therefore possible to vote by handing in any paper containing the text of the question, adding either Yes or No.

Those who were eligible to vote as males over the age of 21 constituted about 28 percent of the resident population; this approximate figure is obtained by considering those over the age of 21 as equal to 55 percent of the inhabitants and excluding the female population (50 percent), according to data taken from the 1871 census.[27] According to the Austrian census of 1857, compared to the total population, men over 21 years of age were 27% in the Venetian provinces (624 728 out of 2 306 875)[28] and 28% in the five districts of Mantua that remained in the empire after 1859 (40 461 out of 146 867).[29]

The question concerned the accession of the Venetian provinces (which at the time included the provinces of today's central-western Friuli) and Mantua to the Kingdom of Italy.

| Text of the question |

|---|

| We declare our union with the Kingdom of Italy under the monarchical-constitutional government of King Victor Emmanuel II and his successors. |

Voter turnout[edit]

Voter turnout was very high, exceeding 85 percent of those eligible to vote.[31] In the Padua district alone 29 894 voters voted,[32] or about 98 percent of those eligible.[33]

In the municipality of Venice, there were 30,601 eligible voters, but 4,000 more people voted (34,004 yes, 7 no, and 115 null), as military personnel and exiles who had returned were also allowed to vote.[34]

The vote of the Slovenian minority[edit]

The participation of the Slovenian-speaking Friulian minority of the so-called Benecija or Friulian Slavia (located in today's Udine province) in the 1866 plebiscite,[35] was particularly significant.[36] The Austrian Empire, in fact, after the Treaty of Campo Formio had annulled the legal,[37] linguistic and fiscal autonomy once granted by the Serenissima to the Slovenian community, which also for this reason adhered to the Risorgimento ideas,[38] which increasingly expanded after the brief interlude of 1848. The anti-Austrian vote of the Slovenes was unanimous: out of 3,688 voters there was only one ballot against the Kingdom of Italy.[39] The passage to the Kingdom of Italy brought many economic, social and cultural changes for that territory,[40] but it also initiated a policy of Italianization of the Natisone and Torre Valleys,[41] which in the decades following the plebiscite fueled a progressive feeling of disappointment in the hopes of recognition of Slovenian identity.

Voting outside the Venetian borders[edit]

In various cities in the Kingdom of Italy there were ballots for Venetian emigrants and exiles, as Article 10 of the decree stated that “all Italians from the liberated provinces who were, either for reasons of public service or for any other reason in any part of the Kingdom” could vote; in Turin, for example, there were 757 voters, all for Yes.[42]

In Florence, the vote became a public demonstration:

Florence, October 21, 1866

The Venetians and Mantovans residing in Florence gathered at noon today at the municipal palace in order to go in solemn form to make their vows for the union of their native land with Italy. They numbered several hundred, and preceded by the band of the National Guard and by flags bearing the cross of Savoy and the lion of St. Mark they proceeded along the streets of the Tornabuoni, the Cerretani, Piazza del Duomo, Via de' Calzaioli and Piazza della Signoria to the residence of the Praetors in the Uffizi Palace.

The applauding people accompanied them along the street, and from their windows they waved their flags in exultation.

— La Nazione, October 22, 1866[43]

The women's vote[edit]

Although not required (as suffrage was only for men at the time), women in Venice, Padua, Dolo, Mirano and Rovigo also wanted to cast their votes.[44] Even in Mantua, women, although not allowed to vote, wanted to bring their support: about 2,000 votes were collected in separate ballot boxes.[45]

Venetian women sent a message to the king:

Men believed themselves to be wise and just, when they decreed that the one, whom they here call the most exalted part of mankind, should be excluded from participating with her action in all that pertains to the government of the public affairs. The women of Venice do not arrogate to themselves the right of judging such a law, but they proclaim in the face of the world that never did their sex feel its bitterness and humiliation more deeply than in this circumstance, in which the people are called upon to declare whether they wish to unite with the common fatherland under the glorious scepter of Your Majesty and His august successors. But if they are forbidden to lay in the ballot box that "yes" which will unite Italy, let them not, however, be deprived of having it otherwise brought to the feet of Your Majesty. Accept therefore, O magnanimous Sire, this cry that spontaneously, unanimously, ardently bursts forth from the depths of our hearts: - Yes: we want, as do our brothers, the union of Venice with Italy under the scepter of Victor Emmanuel and his successors!

— Gazzetta di Mantova, October 25, 1866[46]

In the press of the time, the patriotic nature of this participation was emphasized, neglecting the hints of protest (bitterness and humiliation) and women's claim to the right to vote.[47]

Results[edit]

On October 27 in Venice, in the Scrutiny Room of the Doge's Palace, the counting of votes took place. After a brief speech by Sebastiano Tecchio, president of the Court of Appeals, the court councillors announced the results for the nine provinces.[48][49]

| Province | Yes | No | Null votes[50] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belluno | 37,636 | 2 | 5 |

| Mantua | 37,000 | 2 | 36 |

| Padua | 84,375 | 4 | 1 |

| Rovigo | 33,696 | 8 | 1 |

| Treviso | 84,524 | 2 | 11 |

| Udine | 105,050 | 36 | 121 |

| Venice | 82,879 | 7 | 115 |

| Verona | 85,589 | 2 | 6 |

| Vicenza | 85,930 | 5 | 60 |

| From other provinces of the Kingdom | 5,079 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 641,758 | 69 | 370 |

The announcement of the results was first made in the Scrutiny Hall and was then repeated from the balcony of the Doge's Palace.[48]

Due to the failure to count votes from some municipalities in the Rovigo district (5,339 votes for “yes,” no "no" votes, and one null ballot) and 149 votes from emigrants (all positive), the Court of Appeals was forced to correct the results at its session on October 31, 1866:[51][52]

| Total | Percentage | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electors | n/a. | 100,00 | |

| Voters | 647,686 | n/a. | (out of no. electors) |

| Null votes | 371 | 0,06 | (out of no. voters) |

| Votes | Percentage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFFIRMATIVE ANSWER | 647,246 | 99,99 | (out of no. valid votes) | |

| NEGATIVE ANSWER | 69 | 0,01 | (out of no. valid votes) | |

| Total of valid votes | 647,315 | 99,94 | (out of no. voters) | |

Different versions of the results can be found published:[53]

- the plaque placed in Piazza delle Erbe in Padua reports the final data of the Court of Appeal (647 246 in favor and 69 against);

- the plaque placed in the access corridor to the Scrutiny Hall on the first noble floor of the Doge's Palace in Venice seems to report the first data of the Tribunal, but with a difference in the number of void ballots (641 758 in favor, 69 against and 273 null, for a total of 642 100 voters);

- the plaque on the monument to Victor Emmanuel II placed at the Riva degli Schiavoni in Venice also shows the early data from the Tribunal;

- Denis Mack Smith, in History of Italy, reports 641 000 in favor;

- others cite a population of 2 603 009, with 647 426 voting and 69 voting against.

Criticism at the time[edit]

The unanimous adherence to the plebiscite was thus explained in an article in La Civiltà Cattolica, published in Rome, which at that time was engaged in the Roman question in defense of temporal power:

The fact is that amid great jubilation, to the sound of bells in certain places, the people rushed to cast their ballots into the ballot box. Depositing a no was, besides being useless, the same as voting for anarchy; everyone deposited the yes.

— La Civiltà Cattolica, 1866[54]

Spirito Folletto on November 8, 1866 published a series of cartoons depicting examples of plebiscite voters:[55]

- I voted "no" out of caution and out of fear of seeing them return

- Austrian captain and decorated with the black eagle, could he vote "yes"?

- - Did you say yes or no? - How would I know?... He gave me a piece of written paper, and eight pennies; I threw the paper in the pit and the money in the pocket...

- Pretending to vote "yes" and voting "no," here is the ultimate example of cunning.

- I will never vote for libertines - I am a good Catholic.

Events following the plebiscite[edit]

Restitution of the iron crown[edit]

On April 22, 1859, due to the advance of the Piedmontese in the Milanese area, the Austrians decided to transfer to Vienna the iron crown, an ancient and precious symbol used since the Middle Ages for the coronation of the kings of Italy, which was kept at the Treasury of the Cathedral of Monza.[56]

The restitution of the crown to Italy was the subject of specific notes attached to the peace agreement,[57][58] and was officially handed over on October 12, 1866, by Austrian General Alexander von Mensdorff to the Italian representative General Menabrea; the latter, after the treaty was signed, returned from Vienna carrying the crown to Turin, and during the trip stopped in Venice and showed it to Royal Military Commissioner Thaon di Revel.[59]

A plaque placed in Calle Larga dell'Ascensione[60][61] indicates October 25, 1866 as the date of the presence in Venice of the crown returned to Italy.

Delivery of results to Turin[edit]

At midnight on November 2, the Venetian delegation left Venice on a special train, which, after a stop of several hours in Milan (where the Venetian representatives were festively welcomed by the Milanese municipal administration)[62] arrived at Turin station the next day, Saturday, November 3, at 2 p.m., greeted by festive cannon shots[63] and received by the Turin city council and conducted through a sumptuous procession[64] to the Europa Hotel, from whose balcony Commander Tecchio delivered an address to the crowd below.

On Sunday, November 4, 1866, in the Throne Room of Turin's Royal Palace, a Venetian delegation delivered the results of the plebiscite to King Victor Emmanuel II; the delegation was composed as follows:[65]

- Giambattista Giustinian, podestà of Venice;

- Giuseppe Giacomelli, mayor of Udine;

- Edoardo De Betta, podestà of Verona;

- Francesco De Lazara, podestà of Padua;

- Gaetano Costantini, podestà of Vicenza;

- Antonio Pernetti, acting podestà of Mantua;

- Antonio Caccianiga, mayor of Treviso;

- Francesco Derossi, podestà of Rovigo;

- Francesco Piloni, acting mayor of Belluno;

Sebastiano Tecchio, president of the Court of Appeals of Venice, was also present.

Giambattista Giustinian delivered the official speech:

Sire, the event that recently took place in the Venetian Provinces and those of Mantua, and of which we are honored today to present you with the splendid result, will be remembered by later generations ... Yes, O sire, this plebiscite, which to us seemed superfluous, but we gladly accepted, as the one that offered us the opportunity to affirm once more what all Europe knew, succeeded so broadly and in such harmony that we almost marveled at ourselves who made it, if nothing could succeed again what pertains to our devotion to you and your dynasty and affection for the Italian homeland. Those 647,246 yeses, collected in the ballot boxes of our Provinces and of so many other parts where by chance there were Venetians ... offer to all Europe a novel testimony to Italian concord ...[66]

To which the king replied with these words:

Gentlemen, today is the most beautiful day of my life. Now it is 19 years since my father proclaimed from this city the war of National Independence; on this day, his name day, you, gentlemen, bring me the manifestation of the popular will of the Venetian provinces, which now, reunited with the great Italian fatherland, declare by the fact to be fulfilled the vow of my august father. You reconfirm by this solemn act what Venice did since 1848, and knew how to maintain to this day with such admirable constancy and self-sacrifice. In this day, every vestige of foreign domination disappears forever from the Peninsula. Italy is now made, if not completed: it is now up to the Italians to know how to defend it, and make it prosperous and great. The Iron Crown was also returned on this solemn day to Italy, but to this crown I place before the one dearest to me, made with the love and affection of the peoples.[66]

At the end of the speeches, the Iron Crown of Theodelinda, returned by Austria, was presented and handed to the king. Despite its high symbolic value,[67] Victor Emmanuel II “with indifference” had the crown placed on the throne.[63] The crown was returned to Monza Cathedral on December 6 of the same year.[56]

On the same day Royal Decree No. 3300 of annexation was issued, by which “the provinces of Venice and those of Mantua are an integral part of the Kingdom of Italy.”[68] The decree was converted into law on July 18, 1867 (approved by the House on May 16, 1867 with 207 votes for and four against; approved by the Senate on May 25, 1867 with 83 votes for and one against).[69]

Entry of Victor Emmanuel II into Venice[edit]

On November 7, 1866, with the entry of Victor Emmanuel II into the city of Venice, the political phase of the Third Italian War of Independence also ended.[70]

Victor Emmanuel II arrived by royal train at Venezia Santa Lucia railway station at around 11:00 a.m., preceded by blank cannon shots fired from Fort Marghera. The city was festively decorated, with tricolored cockades and posters of greetings (among which some, printed by a certain Simonetti, bore the anagram “Victor Emmanuel - O King, do you love Veneto? Look! Veneto is yours!!!"). The king, accompanied by his sons Umberto and Amedeo, was welcomed by the city authorities and was taken to the royal boat, led by 18 rowers in costume, which traveled all along the Grand Canal escorted by a grand procession of gondolas, greeted by a large audience. Upon arriving at the Doge's Palace, the notary Bisacco officially delivered to the king the 1848 deed by which the Republic of St. Mark had already sworn allegiance to the Savoy.[71] The festivities continued uninterruptedly for six days, with gala performances at the Teatro La Fenice, fireworks, masquerade balls, gas illuminations and serenades. The event was followed and described by some 1,200 journalists and correspondents who came to Venice from all over the world.[71]

-

Pietro Bertoja, The arrival of Victor Emmanuel II in Venice on November 7, 1866

-

Victor Emmanuel II on the Grand Canal

-

Frans Vervloet, Entrance of Victor Emmanuel at the Rialto (sketch from life, November 7, 1866)

-

Gerolamo Induno, Entrance of Victor Emmanuel II in Venice

-

Arrival of Victor Emmanuel at the Doge's Palace (The Illustrated London News)

-

Entry of Victor Emmanuel into Venice in 1866, reception by the Patriarch of Venice in front of St. Mark's Church

-

Victor Emmanuel II receives the blessing of the patriarch in St. Mark's Square

-

Visit to Venice by Victor Emmanuel II

-

Grand Canal bridge decorated for official visit

-

Boat used by Victor Emmanuel II

-

Decoration of the flag of Venice

-

St. Mark's Square during the festivities

There still remained under the Austrian Empire the territories that had never been included in the now defunct Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia, namely Trentino, the city of Trieste and areas of the Dalmatian coast with significant Italian presence; this would reinvigorate irredentist sentiments and provide the main motive for supporters of Italy's entry into the war against Austria during World War I (also known as the Fourth Italian War of Independence).

The Order of the Crown of Italy[edit]

By decree of February 20, 1868, Victor Emmanuel II established the Order of the Crown of Italy with specific reference to the annexation of Veneto:

Having not long since consolidated, by the annexation of Venice, the independence and unity of Italy, we have determined to consecrate the memory of this great fact, by means of the establishment of a new order of knighthood, destined to reward the most distinguished merits of both Italians and foreigners, and especially those that directly concern the interests of the nation.

— Royal Decree No. 4251 of February 20, 1868

The decorations for all ranks of the order contained an image of the Iron Crown; the decoration for the highest rank (Knight of the Grand Cross or Grand Cordon) bore the inscription VICT. EMMAN. II REX ITALIAE - MDCCCLXVI (Victor Emmanuel II King of Italy - 1866).

The reconstitution of the province of Mantua[edit]

In 1859, after the Second War of Independence, the province of Mantua, as part of the Austrian Empire, had been deprived of the districts west of the Mincio River, which passed to the then Kingdom of Sardinia and were divided between the provinces of Brescia and Cremona.

With the annexation of the province of Mantua to the Kingdom of Italy, a request was made to restore the historical boundaries; reunification took place in February 1868.[72]

Discussions on the validity of the plebiscite[edit]

Beginning in the mid-1990s,[73] some historians, mostly related to the Veneto regionalist movement,[74][75] began to challenge the validity of the plebiscite by imputing strong political pressure, a series of alleged frauds, and improper conduct of the voting to the Savoys,[76] adding that nineteenth-century Venetian society was predominantly rural with a still high illiteracy rate and large strata of the population were ready to accept the directions of the “upper classes.”

Other historians and constitutionalists reject this anti-Risorgimento reconstruction,[77] pointing out on the one hand that the plebiscite was only a validation of the diplomatic activity following the Peace of Prague, and on the other hand pointing out the great festive atmosphere that accompanied the vote and lasted until the triumphal entry of Victor Emmanuel II into Venice on November 7, 1866, therefore ruling out altogether that the annexation was not desired by the people of Veneto and Mantua.

On the night of May 8-9, 1997, a group of people calling themselves the “Veneta Serenissima Armata” (better known as the Serenissimi) militarily occupied the bell tower of St. Mark's in Venice: these activists, who were later arrested and convicted, claimed to have done historical research and discovered elements that, in their opinion, would have invalidated, among other things, the plebiscite ratifying the annexation to the Kingdom of Italy in 1866,[78] characterized, again according to them, by alleged fraud and violations of international agreements signed during the Armistice of Cormons and the Treaty of Vienna.

In 2012, the Veneto Regional Council passed a resolution stating that “the accession of Veneto to the Italian Kingdom with the referendum of October 21 and 22, 1866, matured with an instrument of direct consultation, characterized, in truth, by a series of fraudulent actions implemented by the Kingdom of Italy.”[79]

In September 2016, the Veneto Region sent to ninety libraries in Veneto a copy of the book “1866 la grande truffa: il plebiscito di annessione del Veneto all'Italia” by Ettore Beggiato, which supports the thesis of fraud,[80] reinvigorating the debate among historians.[81][82][83][84]

On April 24, 2017, Regional President Luca Zaia called an advisory referendum to ask[85] resident citizens the question, “Do you want the Veneto region to be granted additional forms and conditions of autonomy?”,[86] and then demand similar governing powers from neighboring special-status regions. The date of the vote, chosen jointly with Lombardy where a similar consultation was held, was symbolically on October 22, 2017, precisely on the 151st anniversary of the October 21-22, 1866 voting, also to “give an answer” to the historic plebiscite.[87]

Formal repeal of the annexation decree[edit]

In December 2010, Roberto Calderoli, then minister for Regulatory Simplification in the Fourth Berlusconi government, announced the approval of the so-called “law-killing decree.”[88] The decree was intended to eliminate from the Italian legal system thousands of laws considered unnecessary or obsolete: however, among the repealed regulations was also Royal Decree No. 3300 of November 4, 1866, as well as its conversion law No. 3841 of July 1867, which had decreed the annexation of the Veneto region to the Kingdom of Italy.[89]

This was in fact a merely formal repeal, since the Republican Constitution on the one hand enshrined the indivisibility of Italy and on the other included Veneto among the Italian regions.[90] Although some journalistic sources report an alleged later corrective decree,[91] Royal Decree No. 3300 of 1866 remained formally repealed.[92]

Filmography[edit]

- Senso, directed by Luchino Visconti (1954) based on the novel by Arrigo Boito

- Il leone di vetro, directed by Salvatore Chiosi (Italy, 2014)

See also[edit]

- 2017 Venetian autonomy referendum

- Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia

- Third Italian War of Independence

- Proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy

References[edit]

- ^ Giordano (2008, p. 66).

- ^ Lombardy had been ceded to the Kingdom of Sardinia by the Treaty of Zurich in 1859.

- ^ Ministero degli Affari Esteri (1983, pp. 329–330).

- ^ Ministero degli Affari Esteri (1983, pp. 331–333).

- ^ By 1848 in the province of Padua alone, 62259 votes had been collected for immediate merger, and 1002 for deferred merger.

- ^ On January 11, 1860 Gloria had written, "It is asserted that many municipalities of the Venetian provinces renewed in the past days the fusion to Piedmont made in 1848. The fact is that our Podestà, the Aldermen and the Secretary signed a printed form bearing this renewal. The civic courage of these representatives of the city shows the spirit of the citizens toward the Austrian government.

- ^ Comitato (1916, p. 423-424).

- ^ a b c See Peace of Vienna - October 3, 1866.

- ^ On July 4, 1848, in Venice the National Assembly had approved by 127 votes to 6 the proposal for the immediate merger of Venice into the Sardinian States with Lombardy and on the same conditions as the same, and a few days later the Turin parliament decreed the immediate union with the kingdom of Lombardy, and the provinces of Treviso, Padua, Vicenza and Rovigo; the shortly following Piedmontese defeat and the armistice of Salasco would render all these attempts at union null and void, see p. 22 in Consiglio regionale del Veneto (2012). "La Rivoluzione a Venezia". Consiglio regionale del Veneto: 22–24.

- ^ a b c d e f g "La procedura per la cessione del Veneto all'Italia". Gli archivi dei regi commissari nelle province del Veneto e di Mantova 1866. Vol. 1. Roma. 1968. pp. 3–9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c "Gazzetta ufficiale del Regno d'Italia". 19 October 1866. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016.

- ^ Archives diplomatiques (1866, pp. 374–375).

- ^ "Toscana e Stati annessi". La Civiltà Cattolica: 374–375. 1866. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016.

- ^ Dubarry (1869, p. 160).

- ^ Letter from the military commissioner in the Venetian provinces Genova Thaon di Revel to Foreign Minister Emilio Visconti Venosta, in Ministero degli Affari Esteri (1983, pp. 476–477).

- ^ Letter from the minister of foreign affairs to Costantino Nigra, in. Ministero degli Affari Esteri (1983, p. 478).

- ^ Dubarry (1869, pp. 166, 172).

- ^ a b Dubarry (1869, p. 168).

- ^ Archives diplomatiques (1866, p. 383).

- ^ Archives diplomatiques (1866, pp. 383–385).

- ^ a b Comitato (1916, p. 314).

- ^ Il testo riporta erroneamente il giorno 22. Cfr. Recueil des traités de la France. Vol. 6. Paris. 1868. pp. 608–610.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Comitato (1916, p. 317).

- ^ Cfr. «Cessione della Venezia compiuta. La bandiera Reale Italiana sventola dalle antenne di piazza San Marco. Le truppe Italiane entrano fra mezzo popolazione esultante. Gioja spinta quasi al delirio», "Dispaccio telegrafico del Commissario del Re". 19 October 1866. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016.

- ^ Alessandro Mocellin (19 October 2011). "Il Veneto nel 1866 non è mai stato ceduto all'Italia (prima parte)". Il Mattino di Padova. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Operazioni di voto per il plebiscito nella prima sezione elettorale di Venezia" (PDF). Gli archivi dei regi commissari nelle province del Veneto e di Mantova. 2. Roma: Ministero dell'Interno: 138–140. 1968. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2016.

- ^ Popolazione classificata per età, sesso, stato civile ed istruzione elementare (PDF). Vol. 2. Roma. 1875. pp. 7, 32. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Statistische Übersichten über die Bevölkerung und den Viehstand von Österreich. Nach der Zählung vom 31 October 1857. Wien. 1859. pp. 414–415.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Statistische Übersichten über die Bevölkerung und den Viehstand von Österreich. Nach der Zählung vom 31 October 1857. Wien. 1859. pp. 144–145.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Located in Campo San Fantin.

- ^ Michieli (1988, p. 297).

- ^ G. Solitro (1916). "Padova nei primi mesi della sua liberazione (12 luglio-23 ottobre 1866)". L'ultima dominazione austriaca e la liberazione del Veneto nel 1866 : memorie. p. 428.

- ^ Raffaele Vergani (1967). "Elezioni e partiti a Padova nel '66-'70". Rassegna storica del Risorgimento: 255. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016.

- ^ Distefano & Paladini (1996, p. 275).

- ^ "Così gli sloveni nel 1866 entrarono nel Regno d'Italia". Il Piccolo. 21 October 2016. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- ^ "Le Valli fra Italia, Austria e il rimpianto di Venezia". Messaggero Veneto. 19 October 2016. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- ^ In particular, Austria abolished the communion of land, which was divided and leased to private individuals.

- ^ See to this end the poem Predraga Italija, preljubi moj dom (Dearest Italy, Beloved My Home) by Don Pietro Podrecca and the Garibaldian experience of Carlo Podrecca.

- ^ Michela Iussa. "Le Valli del Natisone dal risorgimento all'avvento del fascismo". Lintver. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- ^ "Posledice plebiscita na posvetu / Il post plebiscito in un convegno". Dom (in Slovenian and Italian). 20 October 2016. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- ^ "Benečija in Rezija 150 let v Italiji / Benecia e Resia da 150 anni in Italia". Dom (in Slovenian and Italian). 14 October 2016. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016.

- ^ L'Italia nei cento anni del secolo XIX (1801-1900) giorno per giorno illustrata. Vol. 4. p. 908.

- ^ "Plebiscito dei Veneti e Mantovani residenti in Firenze". La Nazione: 1. 22 October 1866. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016.

- ^ Nicolò Biscaccia. Cronaca di Rovigo, 1866. p. 93. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016.

- ^ Manifesto del 25 ottobre 1866 del Commissario del re, Guicciardi.

- ^ "(senza titolo)". Gazzetta di Mantova: 2. 25 October 1866. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016.

- ^ Nadia Maria Filippini (2006). Donne sulla scena pubblica: società e politica in Veneto tra Sette e Ottocento. Milano: FrancoAngeli. p. 136. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016.

- ^ a b Cronaca della nuova guerra d'Italia del 1866. Rieti. 1866. pp. 573–574. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Thaon di Revel (1890, pp. 162–163).

- ^ Partial data on null votes are indicated only by Thaon di Revel's memoirs, and the total he indicated (366), does not match the partial data.

- ^ "Notificazione del Tribunale d'Appello del 31 ottobre 1866". Raccolta delle leggi decreti e regolamenti pubblicati dal governo del Regno d'Italia nelle provincie venete. Vol. 2. pp. 314–316.

- ^ Le Assemblee del Risorgimento. Atti raccolti e pubblicati per deliberazione della Camera dei Deputati. Vol. 2. Roma. 1911. pp. 727–730.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ettore Beggiato (16 January 1983). "Plebiscito: prima e dopo la truffa". Etnie. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Toscana e stati annessi". La Civiltà Cattolica: 493. 1866. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016.

- ^ "Sì e no del plebiscito". Spirito Folletto: 2–3. 8 November 1866. Immagini: 2 Archived 2016-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, 3 Archived 2016-11-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Rocco Bombelli (1870). Storia della Corona Ferrea dei Re d'Italia. Firenze. pp. 170–178. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Giordano (2008, p. 82).

- ^ "La corona del ferro detta "ferrea"". Monarchic in rete. 12 September 2012. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017.

- ^ Thaon di Revel (1890, p. 176).

- ^ See the plaque placed in Calle Larga dell'Ascensione (Luna Hotel Baglioni) in Venice.

- ^ "Sestiere di San Marco: Calle larga de l'ascension". veneziatiamo.eu. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ^ "Notizie e fatti diversi". Gazzetta Ufficiale del Regno d'Italia (304). 5 November 1866. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016.

- ^ a b Antonio Caccianiga (1889). Feste e funerali. Treviso: Luigi Zoppelli editore. pp. 1–2.

- ^ "Notizie e fatti diversi". Gazzetta Ufficiale del Regno d'Italia (301). 2 November 1866. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016.

- ^ Le Assemblee del Risorgimento. Atti raccolti e pubblicati per deliberazione della Camera dei Deputati. Vol. 2. Roma. 1911. pp. 731–732.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b 1882, p. 100).

- ^ The Iron Crown was used to crown all Italic kings of the past.

- ^ "Regio decreto 4 novembre 1866, n. 3300". Gazzetta Ufficiale: 1. 5 November 1866. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016.

- ^ Le Assemblee del Risorgimento. Atti raccolti e pubblicati per deliberazione della Camera dei Deputati. Vol. 2. Roma. 1911. pp. 734–738.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Giordano (2008, pp. 82–83).

- ^ a b Franzina (1986, p. 31).

- ^ Legge n. 4232, 9 febbraio 1868

- ^ Trabucco & Romano (2007).

- ^ Giovanni Distefano (2008, p. 688).

- ^ Agnoli, Beggiato & Dal Grande (2016, p. 36).

- ^ Beggiato (1999).

- ^ Daniele Trabucco (14 September 2016). "L'analisi". Corriere delle Alpi. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016.

- ^ "Morto Segato, ispirò l'assalto dei Serenissimi a San Marco". Il Giornale. 27 March 2006. Archived from the original on 28 April 2012.

- ^ "Risoluzione n. 44/2012 - Il diritto del popolo veneto alla compiuta attuazione della propria autodeterminazione". Regione del Veneto. 5 October 2012. Archived from the original on 21 March 2014.

- ^ Gian Antonio Stella (16 September 2016). "«Il plebiscito, che truffa»: il libro anti Italia con cui la Regione Veneto «festeggia» l'annessione". Corriere della Sera. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ Ettore Beggiato (6 September 2016). "Libro sul Plebiscito nelle biblioteche, Beggiato: «Non c'è nessuno scandalo»". Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ "La Regione Veneto "festeggia" i 150 anni del Plebiscito con un libro anti-Italia". 6 September 2016. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ Pierluigi Scolé (9 September 2016). "La Regione Veneto e il libro anti-italiano". Corriere della Sera. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ Carlo Lottieri (2 September 2016). "Il plebiscito del Veneto fu una truffa ma la sinistra non vuole dirlo". Il Giornale. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ "La Costituzione". Senato della Repubblica. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017.

- ^ Roberta De Rossi (12 May 2017). "Referendum consultivo per l'autonomia del Veneto: si vota il 22 ottobre". La Nuova di Venezia e Mestre. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017.

- ^ "Zaia: referendum il 22 ottobre - Salvini: «Dopo 30 anni più libertà»". Corriere del Veneto. 21 April 2017. Archived from the original on 26 May 2017.

- ^ "Decreto legislativo 13 dicembre 2010, n. 212, in materia di "Abrogazione di disposizioni legislative statali, a norma dell'articolo 14, comma 14-quater, della legge 28 novembre 2005, n. 246."".

- ^ Alessio Antonini (8 February 2011). "Abrogata per errore dal governo l'annessione del Veneto all'Italia". Corriere del Veneto. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011.

- ^ Luigi Bacialli (10 February 2011). "Il Veneto da 72 ore non è in Italia". Italia Oggi (34): 6.

- ^ Marco Bonet (22 October 2016). "Dai venetisti «anni '20» all'assalto del Campanile, ribellismo mai sopito". Corriere del Veneto. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016.

- ^ "REGIO DECRETO 4 novembre 1866, n. 3300".

Bibliography[edit]

- Archives diplomatiques. Recueil de diplomatie et d'histoire (in French). Vol. IV. Parigi: Librairie diplomatique D'Amymot. 1866.

- Gli archivi dei regi commissari nelle province del Veneto e di Mantova (PDF). Vol. 1. Roma: Ministero dell'interno - pubblicazioni degli Archivi di Stato. 1968. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- Gli archivi dei regi commissari nelle province del Veneto e di Mantova (PDF). Vol. 2. Roma: Ministero dell'interno - pubblicazioni degli Archivi di Stato. 1968. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- I documenti diplomatici italiani. Vol. VII. Roma: Ministero degli Affari Esteri. 1983.

- Francesco Mario Agnoli; Ettore Beggiato; Nicolò Dal Grande (2016). Veneto 1866. Il Cerchio. p. 36.

- Angela Maria Alberton (2012). "Finché Venezia salva non sia": esuli e garibaldini veneti nel Risorgimento (1848-1866). Sommacampagna: Cierre.

- Angela Maria Alberton (2016). Dalla Serenissima al Regno d'Italia: il plebiscito del 1866. Il Gazzettino.

- Ettore Beggiato (1999). 1866 la grande truffa: il plebiscito di annessione del Veneto all'Italia. Editoria universitaria.

- Adolfo Bernardello (1997). Veneti sotto l'Austria. Ceti popolari e tensioni sociali (1840-1866). Verona: Cierre.

- Otello Bosari (2011). L'annessione delle province del Veneto e di Mantova al Regno d'Italia nel 1866: la testimonianza degli archivi dei Commissari del Re. Associazione Culturale Aldo Modolo. p. 158.

- 1866 - Il Veneto all'Italia e il plebiscito a Venezia, Treviso e Padova. Treviso: Editoriale Programma. 2016.

- Renato Camurri (2002). "Storia di Venezia". Enciclopedia Italiana. Treccani.

- Eugenio Curiel (2012). ElioFranzin (ed.). Il Risorgimento nel Veneto. Padova: Sapere.

- Paolo De Marchi, ed. (2011). Il Veneto tra Risorgimento e unificazione (PDF). Verona: Consiglio Regionale del Veneto - Cierre edizioni.

- Giovanni Distefano. Atlante storico di Venezia (II ed.). 2008: Supernova.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Giovanni Distefano; Giannantonio Paladini (1996). Storia di Venezia 1797-1997 - 2. La Dominante Dominata (II ed.). Venezia: Supernova-Grafice Biesse.

- Armand Dubarry (1869). Deux mois de l'histoire de Venise (1866) (in French). E. Dentu.

- Emilio Franzina (1986). L'unificazione. Bari: Laterza.

- Giancarlo Giordano (2008). Cilindri e feluche. La politica estera dell'Italia dopo l'Unità. Roma.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Adriano Augusto Michieli (1988). Storia di Treviso (III ed.). Treviso: SIT.

- Piero Pasini, ed. (2016). "L'altro anniversario 1866-2016: Orgogli e pregiudizi venetisti e anti-italiani". Venetica (1). Cierre edizioni.

- Mauro Pitteri, ed. (2011). Diario veneto del Risorgimento: 1848-1866. (introduzione di Paul Ginsborg; prefazione di Raffaele Bonanni). CISL Veneto.

- Sebastiano Porcu (March 2015). "Il plebiscito del Veneto del 1866". I Plebisciti nell'Italia del Risorgimento.

- Paolo Preto (2000). Il Veneto austriaco 1814-1866. Fondazione Cassamarca.

- Daniele Trabucco; Sergio Romano (2007). L'Antirisorgimento e il passato che non c'è. Milano: Rizzoli.

- Genova Giovanni Thaon di Revel (1890). La cessione del Veneto. Ricordi di un commissario regio militare. Milano: Dumolard. OCLC 56987382.

- Genova Giovanni Thaon di Revel (2003). Venezia 1866: dall'occupazione asburgica all'occupazione sabauda dei territori veneti. La cessione del Veneto. Editoria Universitaria Venezia.

- Comitato regionale veneto per la storia del risorgimento italiano (1916). L'ultima dominazione austriaca e la liberazione del veneto nel 1866. Memorie di Filippo Nani Mocenigo - Ugo Botti - Carlo Combi - Antonino Di Prampero - Manlio Torquato Dazzi e Giuseppe Solitro. Chioggia: Stab. Tip. Giulio Vianelli italiano.

- Anonimo (1882). Memorie del re galantuomo. Milano: Ferdinando Garbini.

External links[edit]

- "Alliance with Italy (October 22, 1866)". C2D - Centre for Research on Direct Democracy. Zentrum für Demokratie Aarau. Retrieved 2021-10-18.