User:Jessicasener/sandbox

| This is a user sandbox of Jessicasener. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

Copied from: Alice Walker

Alice Walker (born February 9, 1944) is an African American novelist, short story writer, and poet. She wrote the novel The Color Purple (1982), for which she won the National Book Award for hardcover fiction and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.[1][2] She also wrote the novels Meridian (1976) and The Third Life of Grange Copeland (1970), among other works. Walker is also an activist, fighting for civil rights, social justice, gender equality, and political change.[3] Committed to feminism, Walker coined the term "womanist" to mean "A black feminist or feminist of color" in 1983.[4]

Early life[edit]

Alice Malsenior Tallulah-Kate Walker was born in Eatonton, Georgia, a rural farming town, to Willie Lee Walker and Minnie Tallulah Grant.[5][6] Both of Walker's parents were sharecroppers, though her mother would work as a seamstress to earn extra money. Walker, the youngest of eight children, was first enrolled in school when she was just four years old at East Putnam Consolidated.[5][7]

Walker sustained injury to her right eye when she was eight years old after one of her brothers fired a BB gun.[8] Because her family did not have access to a car, Walker did not receive immediate medical attention, causing her to become permanently blind in that eye. It was after the injury to her eye that Walker began to take up reading and writing.[5] The scar tissue was removed when Walker was 14, but a mark still remains and is described in her essay "Beauty: When the Other Dancer is the Self."[9][7]

Because the schools in Eatonton were segregated, Walker attended the only high school available to blacks: Butler Baker High School.[7] She went on to become valedictorian and enrolled in Spelman College in 1961 after being granted a full scholarship by the state of Georgia for having the highest academic achievements of her class.[5] She found two of her professors, Howard Zinn and Staughton Lynd, to be great mentors during her time at Spelman, but transferred two years later.[7] Walker was offered another scholarship, this time from Sarah Lawrence College in New York, and after the firing of her Spelman professor, Howard Zinn, Walker accepted the offer.[9] Walker fell pregnant at the start of her senior year and proceeded to have an abortion; this experience, as well as the bout of suicidal thoughts that followed, inspired much of the poetry found in Once, Walker's first collection of poetry.[9] Walker graduated from Sarah Lawrence in 1965.[9]

Writing career[edit]

Walker wrote the poems of her first book of poetry, Once, while she was studying in East Africa and during her senior year at Sarah Lawrence College.[10] Walker would slip her poetry under the office door of her professor and mentor, Muriel Rukeyser, when she was a student at Sarah Lawrence. Rukeyser then showed the poems to her agent. Once was published four years later by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.[11][9]

Following graduation, Walker briefly worked for the New York City Department of Welfare before returning South. She took a job working for the Legal Defense Fund of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Jackson, Mississippi.[7] Walker also worked as a consultant in black history to the Friends of the Children of Mississippi Head Start program. She later returned to writing as writer-in-residence at Jackson State University (1968–69) and Tougaloo College (1970–71). In addition to her work at Tougaloo College, Walker published her first novel, The Third Life of Grange Copeland, in 1970. The novel explores the life of Grange Copeland, an abusive, irresponsible sharecropper, husband and father.

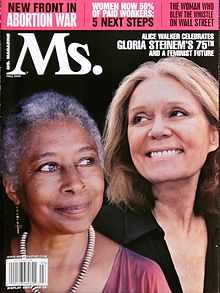

In the fall of 1972, Walker taught a course in Black Women's Writers at the University of Massachusetts Boston.[12] Before becoming editor of Ms. Magazine in 1974, Walker and, fellow Hurston scholar, Charlotte D. Hunt discovered Zora Neale Hurston's unmarked grave in Ft. Pierce, Florida.[7][13] Walker's 1975 article "In Search of Zora Neale Hurston," published in Ms. Magazine, helped revive interest in the work of this African-American writer and anthropologist.[13]

In 1976, Walker's second novel, Meridian, was published. Meridian is a novel about activist workers in the South, during the civil rights movement, with events that closely parallel some of Walker's own experiences. In 1982, she published what has become her best-known work, The Color Purple. The novel follows a young, troubled black woman fighting her way through not just racist white culture but patriarchal black culture as well. The book became a bestseller and was subsequently adapted into the critically acclaimed 1985 movie directed by Steven Spielberg, featuring Oprah Winfrey and Whoopi Goldberg, as well as a 2005 Broadway musical totaling 910 performances.

Walker has written several other novels, including The Temple of My Familiar and Possessing the Secret of Joy (which featured several characters and descendants of characters from The Color Purple). She has published a number of collections of short stories, poetry, and other writings. Her work is focused on the struggles of black people, particularly women, and their lives in a racist, sexist, and violent society. Walker is a leading figure in liberal politics.[14][15][16][17][18]

In 2000, Walker released a collection of short fiction based on her own life called The Way Forward Is With a Broke Heart, exploring love and race relations. In this book, Walker detailes her interracial marriage to Melvyn Rosenman Leventhal, a civil rights attorney who was also working in Mississippi.[19] The two wed on March 17, 1967 in New York City, since their interracial marriage was then illegal in the South, and divorced in 1976.[9] They had a daughter, Rebecca, together in 1969.[7] Rebecca Walker, Alice Walker's only child, is an American novelist, editor, artist, and activist. The Third Wave Foundation, an activist fund, was founded with the help of Rebecca.[20][21] Her godmother is Alice Walker's mentor and co-founder of Ms. Magazine, Gloria Steinem.[20]

In 2007, Walker donated her papers, consisting of 122 boxes of manuscripts and archive material, to Emory University's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library.[22] In addition to drafts of novels, such as The Color Purple, unpublished poems and manuscripts, and correspondence with editors, the collection includes extensive correspondence with family members, friends and colleagues, an early treatment of the film script for The Color Purple, syllabi from courses she taught, and fan mail. The collection also contains a scrapbook of poetry compiled when Walker was 15, entitled "Poems of a Childhood Poetess."

In 2013, Alice Walker published two new books, one of them entitled The Cushion in the Road: Meditation and Wandering as the Whole World Awakens to Being in Harm's Way. The other is a book of poems entitled The World Will Follow Joy Turning Madness into Flowers (New Poems).

Activism and Political Criticism[edit]

Civil Rights[edit]

Walker met Martin Luther King Jr. when she was a student at Spelman College in the early 1960s. She credits King for her decision to return to the American South as an activist in the Civil Rights Movement. She took part in the 1963 March on Washington. Later, she volunteered to register black voters in Georgia and Mississippi.[23][24]

On March 8, 2003, International Women's Day, on the eve of the Iraq War, Walker was arrested with 26 others, including fellow authors Maxine Hong Kingston and Terry Tempest Williams, at a protest outside the White House, for crossing a police line during an anti-war rally. Walker wrote about the experience in her essay "We Are the Ones We Have Been Waiting For."[25]

Feminism[edit]

Walker's feminism specifically includes advocacy for women of color. In 1983, Walker coined the term "womanist" to mean "A black feminist or feminist of color." The term was made to unite women of color and the feminist movement.[4] She said, "'Womanism' gives us a word of our own." [26]

Israeli-Palestinian Conflict[edit]

In January 2009, Walker was one of over 50 signatories of a letter protesting the Toronto International Film Festival's "City to City" spotlight on Israeli filmmakers, and condemning Israel as an "apartheid regime."[27]

Two months later, Walker and 60 other female activists from the anti-war group Code Pink traveled to Gaza in response to the Gaza War. Their purpose was to deliver aid, to meet with NGOs and residents, and to persuade Israel and Egypt to open their borders with Gaza. She planned to visit Gaza again in December 2009 to participate in the Gaza Freedom March.[28]

On June 23, 2011, Walker announced plans to participate in an aid flotilla to Gaza that attempted to break Israel's naval blockade.[29][30] Her participation in the 2011 Gaza flotilla prompted an op-ed, headlined "Alice Walker's bigotry," written by American attorney and law professor Alan Dershowitz in The Jerusalem Post. Dershowitz said, by participating in the flotilla to evade the blockade, she was "provid[ing] material support for terrorism."[31]

She is a judge member of the Russell Tribunal on Palestine. Walker supports the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions campaign against Israel.[32] In 2012, Walker refused to authorize a Hebrew translation of her book The Color Purple, criticizing what she called Israel's "apartheid state."[33]

In May 2013, Walker posted an open letter to singer Alicia Keys, asking her to cancel a planned concert in Tel Aviv. "I believe we are mutually respectful of each other’s path and work," Walker wrote. "It would grieve me to know you are putting yourself in danger (soul danger) by performing in an apartheid country that is being boycotted by many global conscious artists." Keys rejected the plea.[34]

David Icke[edit]

Also in May of 2013, Walker expressed appreciation for the works of David Icke.[35] On BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs, she said that Icke's book Human Race Get Off Your Knees would be her choice if she could have only one book.[36] Jonathan Kay of the National Post said that Walker's public praise for Icke's book was "stunningly offensive" and that by taking it seriously, she was disqualifying herself "from the mainstream marketplace of ideas."[37]

LGBTQ[edit]

In June 2013, Walker and others appeared in a video showing support for Chelsea Manning, an American soldier imprisoned for releasing classified information.[38]

Personal life[edit]

In 1965, Walker met Melvyn Rosenman Leventhal, a Jewish civil rights lawyer. They were married on March 17, 1967, in New York City. Later that year the couple relocated to Jackson, Mississippi, becoming the first legally married inter-racial couple in Mississippi.[39][40] They were harassed and threatened by whites, including the Ku Klux Klan.[41][page needed] Walker and her husband divorced in 1976.[9]

In the mid-1990s, Walker was involved in a romance with singer-songwriter Tracy Chapman, saying, "It was delicious and lovely and wonderful and I totally enjoyed it and I was completely in love with her but it was not anybody's business but ours."[42] Walker has said she is bisexual out of curiosity.[citation needed][43]

In the late 1970s Walker had moved to northern California. Walker co-founded Wild Tree Press, a feminist publishing company in Anderson Valley, California. She and fellow writer Robert L. Allen founded it in 1984.[44]

Walker's spirituality has also played a great role in her personal life, and influenced some of her most famous novels, like The Color Purple[45]. Her religious views have been defined through an unoppressive womanist perspective[46] as a means to uplift black women. Walker's exploration of religion in much of her writing was greatly inspired by other writers such as Zora Neal Hurston. Some literary critics, such as Alma Freeman, have even said that Walker perceived her as a spiritual sister.[47] Walker wrote, "At one point I learned Transcendental Meditation. This was 30-something years ago. It took me back to the way that I naturally was as a child growing up way in the country, rarely seeing people. I was in that state of oneness with creation and it was as if I didn't exist except as a part of everything."[48]

In honor of her mother, Minnie Tallulah Grant, and paternal grandmother, Walker legally added "Tallulah Kate" to her name in 1994.[7] Minnie Tallulah Grant's grandmother, Tallulah, was Cherokee.[5]

-------------------

Her second book of poetry was published by her mentor, Dudley Randall, of Broadside Press. Randall provided Walker with an introduction to African American academics, for it was after this exposure that Walker's work began to enter the classroom.[5]

Walker has been greatly influenced by Zora Neale Hurston, and is credited with having "almost single handedly rescued Zora Neale Hurston from obscurity."[49] She called attention to Hurston's works, and helped revive the popularity and respect Hurston had received during the Harlem Renaissance. Walker was so moved by Hurston that she and another scholar arranged to have a tombstone put on her unmarked grave;[50] Walker had it inscribed "Southern Genius".[51]

-------

I would like to add to the lead section on Alice Walker’s Wikipedia page, as well as provide additional information about her literature and how it was received, but the biggest undertaking will be removing all signs of plagiarism on this page; a majority of the content consists of close paraphrasing. The plagiarism is so prevalent that I do not think I can fix everything myself, but I will tackle the most obvious errors first and do the best I can. I want to add to the "Writing Career" section, and possibly overlapping with "Early Life," because I don't believe there is enough of an emphasis on her writing here.

Hopson, Cheryl R. “Alice Walker’s Womanist Maternal.” Women's Studies, vol. 46, no. 3, 2017, pp. 221–233.

“Walker, Alice.” Biography Reference Bank (Bio Ref Bank), 01 Mar. 2010, https://libproxy.highpoint.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=brb&AN=203038897&site=ehost-live. Accessed 12 Mar. 2018.

Bates, Gerri. Alice Walker : A Critical Companion. Greenwood Press, 2005. ProQuest ebrary, https://hpulibraries.on.worldcat.org/oclc/62321382.

Bloom, Harold. Alice Walker. Facts on File, Inc, 2000. Bloom's Major Novelists. ProQuest ebrary, libproxy.highpoint.edu/loginurl=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=38601&site=ehost-live.

White, Evelyn C. Alice Walker : A Life. Norton, 2006.

Copied from: Alice Walker

Jessica Joyce

Rhetoric, Identity, & Culture

Dr. Jenn Brandt

19 February 2018

Wikipedia Evaluation: Alice Walker

Alice Walker is a prominent African-American writer with a long list of achievements and involvements, yet the lead section of her Wikipedia article is a mere three sentences; the information provided here only briefly mentions a handful of literary works and achievements. The infobox, on the other hand, is satisfactory. What is most unique is that the infobox on Walker’s page provides a sound bite of Alice Walker speaking. The table of contents is also complete with a variety of coverage and plenty of content.

Unfortunately, the article’s first section, “Early Life,” contains a lot of plagiarized content. The information is cited, but many citations are incorrect or too close to original diction to meet Wikipedia’s requirements. For example, the information within this section is sometimes verbatim for a source cited several paragraphs above. This form of plagiarism appears in the paragraph beginning with “In 1952, Walker was accidentally wounded in the right eye by a shot from a BB gun fired by one of her brothers.” This sentence is linked to citation 9: The Officers of the Alice Walker Literary Society. “About Alice Walker”. Alice Walker Literary Society. Retrieved June 15, 2015. However, this exact sentence is used within source 5: World Authors 1995-2000, 2003. Biography Reference Bank database. Retrieved April 10, 2009. The following quote is taken from source 5

In 1952 Walker was accidentally wounded in the eye by a shot from a BB gun fired by one of her brothers. Because they had no access to a car, the Walkers were unable to take their daughter to a hospital for immediate treatment, and when they finally brought her to a doctor a week later, she was permanently blind in that eye. A disfiguring layer of scar tissue formed over it, rendering the previously outgoing child self-conscious and painfully shy. Stared at and sometimes taunted, she felt like an outcast and turned for solace to reading and to poetry writing. Although when she was 14 the scar tissue was removed--and she subsequently became valedictorian and was voted most-popular girl, as well as queen of her senior class--she came to realize that her traumatic injury had some value: it allowed her to begin "really to see people and things, really to notice relationships and to learn to be patient enough to care about how they turned out," as she has said

The Wiki author of this portion of Walker’s article cites source 5 at the very end of the paragraph; however, Wikipedia has strict rules regarding plagiarism, and the Wiki content is much too similar to the source.

Within “Early Life,” in between paragraphs describing Walker’s time in college and her marriage to Melvyn Leventhal, are a couple sentences regarding Alice Walker’s interest in activism: “Walker became interested in the Civil Rights Movement in part due to the influence of activist, Howard Zinn, who was one of her professors at Spelman College. To continue the activism of her college years, Walker returned to the South from New York. She participated in voter registration drives, campaigns for welfare rights, and children's programs in Mississippi.” While this interest may have arisen during Walker’s younger years, this information is better suited for the section devoted to her activism.

The beginning of “Early Life” includes a description of Walker’s parents. The author here wrote, “Her father, who was, in her words, ‘wonderful at math but a terrible farmer,’ earned only $300 ($4,000 in 2013 dollars) a year.” It should be noted the Wiki author maintains a neutral point of view by including the phrase “in her words.” It is my belief the entire article shows no bias, not even within the sections labeled “Activism” and “Criticism of political views and actions.”

Continuing to discuss the role of Walker’s parents in “Early Life,” the Wiki author wrote, “Minnie Lou worked 11 hours a day for $17 per week to help pay for Alice to attend college.” This sentence is linked with citation 6, but this source no longer exists. The link under references brings the reader to pbs.org, but the page reads “Page Not Found.” Perhaps PBS takes down content after a period of time, but the author of this citation is Alice Walker; therefore, this is not a satisfactory source, regardless. There are a few other instances where Alice Walker is listed as the author of sources listed, but a majority of the sources appear to come from newspapers, the Norton Anthologies, and the Biography Reference Bank database.

Moving to the Talk page, attention is drawn to the warning notice marked at the top. Because parts of Alice Walker’s Wikipedia page relate to the Arab-Israeli conflict, her page is subject to “Active Arbitration Remedies” which means there are editing restrictions in place. The editing restrictions are as follows: “Editing restrictions for new editors,” “Limit of one revert in 24 hours,” “If an edit is reverted by another editor, its original author may not restore it within 24 hours of the revert,” and “All Arab-Israeli conflict-related pages, broadly interpreted, are subject to discretionary changes.”

What follows the warning notice is the article’s rating: B-Class. Alice Walker’s article is being used by nine WikiProjects and all nine recognize her page as B-Class. The nine WikiProjects are as follows: WikiProject Georgia (U.S. state), WikiProject Biography, WikiProject Women writers, WikiProject Indigenous peoples of North America, WikiProject LGBT studies, WikiProject Poetry, WikiProject Gender Studies, WikiProject Feminism, WikiProject Women’s History. Only WikiProject Women writers declares Alice Walker’s page to be of “Top-importance.” Four WikiProjects declare this article to be of “Mid-importance.”

At the bottom of the Talk page, I came across a debate where the phrase “critically acclaimed” in the sentence “She wrote the critically acclaimed novel The Color Purple (1982) for which she won the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction” was deleted with an edit summary of “WP:NPOV.” After “critically acclaimed” was deleted, the original author of that sentence added it back only for it to be deleted again. According to the original author, reliable sources indicate The Color Purple is in fact critically acclaimed; therefore, there is no bias. The person who deleted “critically acclaimed” responded, “Not only is it a POV phrase, it's essentially redundant since you have the awards it won after that. That tells the reader the book has been well received. Best to keep it simple and stick to the facts.” As of now, the revision made stands. The phrase “critically acclaimed” appears only when referencing the movie adaptation directed by Steven Spielberg.

- ^ "National Book Awards - 1983". National Book Foundation. Retrieved March 15, 2012. (With essays by Anna Clark and Tarayi Jones from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.)

- ^ "Fiction". Past winners and finalists by category. The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved March 17, 2012.

- ^ "Alice Walker | Americans Who Tell The Truth". www.americanswhotellthetruth.org. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- ^ a b "Document". gseweb.gse.buffalo.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- ^ a b c d e f Bates, Gerri. Alice Walker : A Critical Companion. Greenwood Press, 2005, https://hpulibraries.on.worldcat.org/oclc/62321382.

- ^ Moore, Geneva Cobb, and Andrew Billingsley. Maternal Metaphors of Power in African American Women's Literature: From Phillis Wheatley to Toni Morrison. University of South Carolina Press, 2017, https://hpulibraries.on.worldcat.org/oclc/974947406.

- ^ a b c d e f g h The Officers of the Alice Walker Literary Society. "About Alice Walker". Alice Walker Literary Society. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ The Officers of the Alice Walker Literary Society. "About Alice Walker". Alice Walker Literary Society. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g World Authors 1995-2000, 2003. Biography Reference Bank database. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- ^ "Once (1968)". Alice Walker The Official Website for the American Novelist & Poet. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ "Muriel Rukeyser was 21 when he ..." Washington Post. 2001-09-16. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- ^ [1] Interview with Barbara Smith, May 7–8, 2003. p. 50. Retrieved July 19, 2017

- ^ a b Miller, Monica (December 17, 2012). "Archaeology of a Classic". News & Events. Barnard College. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ "Alice Walker Booking Agent for Corporate Functions, Events, Keynote Speaking, or Celebrity Appearances". celebritytalent.net. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Alice Walker". blackhistory.com. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Alice Walker". biblio.com. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ Molly Lundquist. "The Color Purple - Alice Walker - Author Biography - LitLovers". litlovers.com. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ "Analyzing Characterization and Point of View in Alice Walker's Short Fiction". Archived 2013-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (2001-02-25). "Interview: Alice Walker". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- ^ a b Rosenbloom, Stephanie (2007-03-18). "Alice Walker - Rebecca Walker - Feminist - Feminist Movement - Children". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- ^ test (2011-01-05). "Third Wave Foundation". Center for Nonprofit Excellence in Central New Mexico. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- ^ Justice, Elaine (December 18, 2007). "Alice Walker Places Her Archive at Emory" (Press release). Emory University.

- ^ Walker Interview transcript and audio file on "Inner Light in A time of darkness", Democracy Now! Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ "Pulitzer-Winning Writer Alice Walker & Civil Rights Leader Bob Moses Reflect on an Obama Presidency", Democracy Now! video on the African-American vote, January 20, 2009. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ "Global Women Launch Campaign to End Iraq War" (Press release). CodePink: Women for Peace. January 5, 2006. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- ^ Wilma Mankiller and others, "Womanism". The Reader’s Companion to U.S. Women’s History. December 1, 1998. SIRS Issue Researcher. Indian Hills Library, Oakland, NJ. January 9, 2013, p. 1.

- ^ Brown, Barry (September 5, 2009). "Toronto film festival ignites anti-Israel boycott". The Washington Times. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ Gaza Freedom March Archived 2009-09-03 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved February 2010.

- ^ Harman, Danna (June 23, 2011). "Author Alice Walker to take part in Gaza flotilla, despite U.S. warning". Haaretz. Tel Aviv. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ Urquhart, Conal (June 26, 2011). "Israel accused of trying to intimidate Gaza flotilla journalists". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Alan M. Dershowitz (June 21, 2012). "Alice Walker's bigotry". Jerusalem Post.

- ^ Tiberias (May 11, 2013). "Palestinians in Israel: Boycotting the boycotters". The Economist. London.

- ^ "Alice Walker says no to Hebrew 'Purple'". Times of Israel. June 19, 2012.

- ^ David Itzkoff (May 31, 2013). "Despite Protests, Alicia Keys Says She Will Perform in Tel Aviv". The New York Times.

- ^ O'Brien, Liam (May 19, 2013). "Prize-winning author Alice Walker gives support to David Icke on Desert Island Discs". The Independent on Sunday. London.

- ^ "Desert Island Discs: Alice Walker". BBC Radio 4. May 19, 2013.

- ^ Jonathan Kay (June 7, 2013). "Where Israel hatred meets space lizards". National Post. Archived from the original on November 30, 2013.

- ^ Gavin, Patrick (June 19, 2013). "Celeb video: 'I am Bradley Manning'". Politico.

- ^ Driscoll, Margarette (May 4, 2008). "The day feminist icon Alice Walker resigned as my mother". The Times. London. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008.

- ^ "Inner Light in a Time of Darkness: A Conversation with Author and Poet Alice Walker". Democracy Now!. November 17, 2006. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- ^ Parsons, Elaine (2015). Ku-Klux : The Birth of the Klan During Reconstruction. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ Wajid, Sara (December 15, 2006). "No retreat". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ^ Reed, Wendy; Horne, Jennifer (2012). Circling Faith: Southern women on spirituality. University of Alabama Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780817317676.

- ^ "Black Book Publishers in the United States". The African American Experience. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03.

- ^ Lackey, Charlie (Spring 2002). "Soul Talk: The New Spirituality of African American Women". MultiCultural Review. 11: 86 – via Women's Studies International.

- ^ Maïnimo, Wirba (Spring 2002). "Black Female Writers' Perspective on Religion: Alice Walker and Calixthe Beyala". Journal of Third World Studies. 19: 117–136 – via Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Freeman, Alma (Spring 1985). "Zora Neale Hurston and Alice Walker: A Spiritual Kinship". Sage. 103: 37–40 – via Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Reed, Wendy; Horne, Jennifer (2012). Circling Faith: Southern women on spirituality. University of Alabama Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780817317676.

- ^ "Walker, Alice." Columbia Guide to Contemporary African American Fiction. Columbia University Press, 2005. Literary Reference Center. Indian Hills Library, Oakland, NJ.

- ^ Extract from Alice Walker, Anything We Love Can Be Saved: A Writer's Activism, The Women's Press Ltd, 1997.

- ^ Alma S. Freeman, "Zora Neale Hurston and Alice Walker: A Spiritual Kinship." Sage 2.1 (Spring 1985), rpt. in Deborah A. Schmitt (ed.), Contemporary Literary Criticism, Vol. 103. Detroit: Gale Research, 1998. Literature Resource Center. Indian Hills Library, Oakland, NJ.