User:Jonharojjashi/First Huna Invasion

| The First Huna Invasion | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Gupta–Hunnic Wars | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Hepthalites | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Unknown | |||||||||

Prelude, Conflicts with the Persians[edit]

Battle of Begram[edit]

References to Kāpiši wine persist in literary works like Dhanapala's Tilakamanjari, describing it as a favored royal beverage with a reddish hue akin to a woman's eyes filled with resentment or the petals of a red lotus. Archaeological findings at Begram reveal ceramic motifs illustrating wine production, featuring jars, vines, grape bunches, and birds, reminiscent of Pompeii's artistry. Additionally, plaster medallions depict symmetrical arches formed by grape leaves and bunches, indicating Begram's historical significance as a grape-growing hub and wine production center.[4]

Recent archaeological endeavors uncovered a sizable wine cellar in Nisa, the former Parthian capital near modern-day Ashkabad, containing nearly 200,000 liters of wine stored in clay pitchers.[5]

Inscriptions on broken pieces of pitchers suggest wine distribution to significant establishments like Nisa's prominent slave-owning palace and temple. The mention of grape wine in the Raghuvamsa underscores the poet's geographical awareness of Kapisi's significance along land routes during Raghu's Persian campaign. After having crossed swords with the Yavanas. Raghu (Chandragupta II) fought a battle against the Parasikas (Persians) somewhere at the valley of Kāpiśi.[6]

Battle of Sistan and the Submission of Varahran[edit]

After the (Persian) Sasanians suffered defeat in the battle of Sistan, which demorilzed the Persian contingents in present day Afghanistan. As the Gupta Army marched northwards to Kapisa Province, Varahran was quick to grasp the political realities and offered his submission to the Gupta Emperor Chandragupta II.[7]

Chandragupta II's expedition against the Hunas[edit]

Gupta cavalry's arrival by the Oxus river[edit]

Bactria was under the Huna occupation in the last quarter of the fourth century AD.[8] The sudden attack into the Oxus valley caught the Transoxiana alliance off-guard. The Pamir Mountains Tocharians were unable to combine with the Hunas (Hephtalites). On hearing the news of the Gupta Empire advanced, the Hephtalites resorted to a tactical retreat to the north of the Oxus River into the plains of southern Uzbekistan. When the Gupta cavalry arrived by the Oxus river on the southern banks, they camped there. Kalidasa poetically described how the cavalry camped on the banks of the river Vankshu in the midst of saffron fields in a verse of his Raghuvamsa:

"...His horses, that had lessened their fatigues of the road by turning from side to side on the banks of the river Vankshu (Oxus), shook their shoulders to which were clung the filaments of saffron..."

Historians studied this as a description of the Gupta cavalry camping on the banks of the Oxus during Chandragupta II's expedition.[9][10]

Kidara's conquest of Gandhara 356 CE and the Battle of the Oxus 399 CE[edit]

Kidara I (Late Brahmi script: ![]()

![]()

![]() Ki-da-ra) fl. 350-390 CE) was the first major ruler of the Kidarite Kingdom, which replaced the Indo-Sasanians in northwestern India, in the areas of Kushanshahr, Gandhara, Kashmir and Punjab.[12]

However, Altekar suggests that Candragupta II attacked the Kidara Kushans. But in the situation also prevailing it isn't insolvable that Chandragupta really raided Balkh or Bactria appertained to as Bahlikas in the inscription. We already saw that Bactria was enthralled by the Hepthalites in about 350 A.D. (Kalidasa refers to the Hunas on the Oxus) and therefore had led to the eventual subjection of Gandhara by Kidara by 356 A.D., the contemporary (Daivaputrashātā of Samudragupta). After Kidara, his successors were known as little Yue-chi. As we have seen Samudragupta was satisfied with the offer of submission of Kidara, and he also claims to have entered the submission of Shāhānushāhī (the Sasanian emperor), substantially to consolidate his vanquishing in the country, and to have some share and control over the renowned Silk-route. The Hunas in Bactria were not a peaceful community and because they posed peril to both Iran and India, and they might have tried to pursue Kidara or his successors in Gandhara, and Fa-hsien refers to Hepthalite king trying to remove Buddha's coliseum from Purushapur. This may indicate Huna invasion in Gandhara some time before Fa-hsien concluded his peregrination in India. It is said that Kidara towards the end of the 4th century had to go northwestwards against the Hunas, leaving his son Piro at Peshawar. It's possible that Kidara might have gained some help from the Gupta emperor. It is thus possible that Chandragupta II led an adventure to Bactria through Gandhara against the Hunas, and this may be appertained to as his crossing of the seven rivers of Sindhu and conquering Bahlika in the Mehrauli Pillar Inscription. This event may be placed towards the end of the 4th century A.D. Chandragupta II's Bactrian expedition also led to the battle of the Oxus with his Gupta cavalry against the Hunas, who were defeated and the Gupta emperor having planted the Gupta flag on the banks of the river of Oxus.[c][14]

Ki-da-ra) fl. 350-390 CE) was the first major ruler of the Kidarite Kingdom, which replaced the Indo-Sasanians in northwestern India, in the areas of Kushanshahr, Gandhara, Kashmir and Punjab.[12]

However, Altekar suggests that Candragupta II attacked the Kidara Kushans. But in the situation also prevailing it isn't insolvable that Chandragupta really raided Balkh or Bactria appertained to as Bahlikas in the inscription. We already saw that Bactria was enthralled by the Hepthalites in about 350 A.D. (Kalidasa refers to the Hunas on the Oxus) and therefore had led to the eventual subjection of Gandhara by Kidara by 356 A.D., the contemporary (Daivaputrashātā of Samudragupta). After Kidara, his successors were known as little Yue-chi. As we have seen Samudragupta was satisfied with the offer of submission of Kidara, and he also claims to have entered the submission of Shāhānushāhī (the Sasanian emperor), substantially to consolidate his vanquishing in the country, and to have some share and control over the renowned Silk-route. The Hunas in Bactria were not a peaceful community and because they posed peril to both Iran and India, and they might have tried to pursue Kidara or his successors in Gandhara, and Fa-hsien refers to Hepthalite king trying to remove Buddha's coliseum from Purushapur. This may indicate Huna invasion in Gandhara some time before Fa-hsien concluded his peregrination in India. It is said that Kidara towards the end of the 4th century had to go northwestwards against the Hunas, leaving his son Piro at Peshawar. It's possible that Kidara might have gained some help from the Gupta emperor. It is thus possible that Chandragupta II led an adventure to Bactria through Gandhara against the Hunas, and this may be appertained to as his crossing of the seven rivers of Sindhu and conquering Bahlika in the Mehrauli Pillar Inscription. This event may be placed towards the end of the 4th century A.D. Chandragupta II's Bactrian expedition also led to the battle of the Oxus with his Gupta cavalry against the Hunas, who were defeated and the Gupta emperor having planted the Gupta flag on the banks of the river of Oxus.[c][14]

) on the iron pillar of Delhi, thought to represent Chandragupta II. Gupta script: letter "Ca"

) on the iron pillar of Delhi, thought to represent Chandragupta II. Gupta script: letter "Ca"  , followed by the conjunct consonant "ndra" formed of the vertical combination of the three letters n

, followed by the conjunct consonant "ndra" formed of the vertical combination of the three letters n  d

d  and r

and r  .[15][16]

.[15][16]Notes[edit]

- ^ " The Mehrauli Pillar Inscription (No.20) describes the digvijaya of a king named Candra (i.e. Candragupta II) in the first verse as stated below :

"He, on whose arm fame was inscribed by the sword, when, in battle in the Vanga countries, he kneaded (and turned) back with (his) breast the enemies who, uniting together, came against him;—he, by whom, having crossed in warfare the seven mouths of the (river) Sindhu, the Vāhlikas;—he by the breezes of whose prowess the Southern ocean is even still perfumed".

We find various readings of the name Vāhlika in literature which are : Vāhlika, Bāhlika, Vāhlīka and Bāhlīka. In our inscription (No. 20) 'Vāhilikāḥ', i.e. Bactria (modern Balkh) region on the Oxus in the northern part of Afghanistan."[2]

- ^ J. F. Fleet's 1888 translation is as follows:[3]

(Verse 1) He, on whose arm fame was inscribed by the sword, when, in battle in the Vanga countries (Bengal), he kneaded (and turned) back with (his) breast the enemies who, uniting together, came against (him); – he, by whom, having crossed in warfare the seven mouths of the (river) Sindhu, the Vahlikas were conquered; – he, by the breezes of whose prowess the southern ocean is even still perfumed; –

- ^ "However, Altekar suggests that Candra Gupta attacked the Kidara Kushāṇas. But in the situation then prevailing it is not impossible that Candra Gupta really invaded Balkh or Bactria referred to as Bāhlika in the inscription. We have seen that Bactria was occupied by the Epthalites in about 350 A.D. (Kalidasa refers to the Hūņas on the Oxus) and thus had led to the eventual conquest of Gandhara by Kidāra by 356 A. D., the contemporary (Daivaputrashātā of Samudra Gupta). After Kidāra, his successors were known as little Yue-chi. As we have seen Samudra Gupta was satisfied with the offer of submission of Kidāra, and he also claims to have received the submission of Shāhānushāhī, (the Sassanian emperor), mainly to consolidate his conquests in the country, and to have some share and control over the famous Silk-route. The Hūṇas in Bactria were not a peaceful community and because a danger to both Iran and India, and they might have tried to pursue Kidāra or his successors in Gandhara, and Fa-hsien refers to Epthalite king trying to remove Buddha's bowl from Purushapur. This may indicate Hūṇa inroad in Gandhāra some time before Fa-hsien concluded his travels in India. It is held that Kidāra towards the end of the 4th century had to proceed N. W. against the Hūṇas leaving his son Piro at Peshwar. It is possible that Kidāra might have received some help from the Gupta emperor. It is therefore possible that Candra Gupta II led an expedition to Bactria through Gandhāra against the Hūṇas, and this may be referred to as his crossing of the seven rivers of Sindhu and conquering Bāhlika in the Mehrauli Pillar Inscription. This event may be placed towards the end of the 4th century A. D."[13]

List of conflicts[edit]

| Conflict | Combatant 1 | Combatant 2 | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| The First Huna Invasion (356–399 CE) |

Gupta Empire | Hephthalites | Gupta victory[17]

|

| Chandragupta II's Huna Expedition (356–399 CE) |

Gupta Empire | Hephthalites | Gupta victory[18][17][19]

|

| Kidara's conquest of Gandhara (356 CE) Location: Gandhara |

Gupta Empire | Hephthalites | Gupta-Kidarite victory[20]

|

| Chandragupta II's Campaign of Balkh (367 CE) Location: Balkh |

Gupta Empire |

Hephthalites | Gupta victory

|

| Battle of the Oxus (399 CE) Location: Oxus valley |

Gupta Empire | Hephthalites | Gupta victory[21]

|

See also[edit]

References[edit]

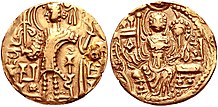

- ^ *1910,0403.26

- ^ Tej Ram Sharma 1978, p. 167.

- ^ R. Balasubramaniam 2005, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Prakash, Buddha (1962). Studies in Indian History and Civilization. Shiva Lal Agarwala. p. 337-338.

- ^ Prakash, Buddha (1962). Studies in Indian History and Civilization. Shiva Lal Agarwala. p. 337-338.

- ^ Prakash, Buddha (1962). Studies in Indian History and Civilization. Shiva Lal Agarwala. p. 337-338.

- ^ Prakash, Buddha (1962). Studies in Indian History and Civilization. Shiva Lal Agarwala. p. Chapter XIII and Chapter XIV.

- ^ " Taking Kālidāsa to be a contemporary of Chandragupta II, we can conclude that the Hūṇas had occupied Bactria in the last quarter of the fourth century AD. " Agrawal, Ashvini (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 240. ISBN 978-81-208-0592-7.

- ^ "The Raghuvamsa Of Kalidasa. With The Commentary Of Mallinatha by Nandargikar, Gopal Raghunath: used/Good rebound full cloth (1982) | Prabhu Book Exports". www.abebooks.co.uk. p. verse 66, Chapter XIII. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Agrawal, Ashvini (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 166. ISBN 978-81-208-0592-7.

- ^ Tandon, Pankaj (2009). "An Important New Copper Coin of Gadahara". Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society (200): 19.

- ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Ahmad Hasan Dani, B. A. Litvinsky, Unesco p.38 sq

- ^ Bindeshwari Prasad Sinha 1974, p. 50–51.

- ^ Agrawal, Ashvini (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 240 & 264. ISBN 978-81-208-0592-7.

- ^ Bandela, Prasanna Rao (2003). Coin Splendour: A Journey into the Past. Abhinav Publications. p. 11. ISBN 9788170174271.

- ^ Allen, John (1914). Catalogue of the coins of the Gupta dynasties. p. 24.

- ^ a b Goyal 1967, p. 280.

- ^ Sinha, Bindeshwari Prasad (1974). Comprehensive History of Bihar. Kashi Prasad Jayaswal Research Institute. p. 50.

- ^ Agrawal, Ashvini (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 240 & 264. ISBN 978-81-208-0592-7.

- ^ Sinha, Bindeshwari Prasad (1974). Comprehensive History of Bihar. Kashi Prasad Jayaswal Research Institute. p. 50.

- ^ Agrawal, Ashvini (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 240 & 264. ISBN 978-81-208-0592-7.