Beer fault

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (October 2021) |

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (March 2023) |

A beer fault or defect is a flavour deterioration caused by chemical changes of organic compounds in beer, either due to improper production processes or storage. Chemicals that can cause flavour defects in beer are aldehydes (such as dactyl organic acids), lipids, and sulfur compounds. Small fluctuations within fermentation byproducts can lead to the concentration of one or more of these chemicals exceeding the standard threshold, creating a flavour defect.

Precision monitoring throughout the brewing process and the use of quality materials determines whether or not defects will be introduced to the beer. Brewers can also determine the quality of their brew through its similarity with the proper taste.

Wine faults[edit]

Improper production or storage can also create wine flavour defects. The chemical changes responsible for wine defects are often caused by factors of the external environment. Poor sanitary conditions of the winery, dirty wine, excessive use of wine barrels, oak, cork, rot, and temperature fluctuations can all create defects of the wine flavour. Beer faults differ from wine faults due to different chemical processes in the creation of the product. In the brewing process of beer, the concentration of inorganic chemical elements can be too high or too low due to improper production. The malting process of joining malt and hops in the brewing process may cause microbial deterioration, which leads to the loss of beer flavour.

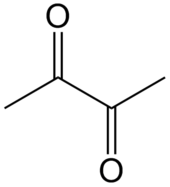

Diacetyl[edit]

Diacetyl is a chemical compound produced in yeast during fermentation and is reabsorbed in the process. Since the external ambient temperature during fermentation is lower than 26 °C (79 °F), diacetyl is absorbed insufficiently, resulting in a threshold of less than 0.04 mg/liter in beer, which gives the beer a mouthfeel similar to cream cheese.[1] This odor will persist over time. Since the decomposition of α-acetolactate produces a large amount of diacetyl, the method can avoid the beer flavour defects caused by diacetyl as follows: boil the container and clean it before the yeast fermentation. The wort should avoid contact with oxygen when the fermentation begins.[2] The temperature is raised by 2°-3° within 2 minutes of the end of the fermentation process, which allows the yeast to reabsorb faster so that the diacetyl content reaches 0.04 mg/L in the beer and does not cross the threshold.

Risotto taste[edit]

Beer can have the taste of glutinous rice if the content of diacetyl in the beer exceeds its low taste threshold. For light-colored lagers, the diacetyl content preferably controls below 0.1 mg/L; for high-grade beer, it preferably remains below 0.05 mg/L. The solution is to increase the a-amino nitrogen content of the wort appropriately. Generally, the content of the 12P wort is controlled to be 180 ± 20 mg / L. Too low will lead to the synthesis and accumulation of a-acetic acid, lactic acid; too high will lead to excess nutrients in the yeast and excessive high alcohol content.[3] Reduce the proliferation multiplication of yeast, generally the multiplication factor ≤ 3. Because the precursors of diacetyl and other yeast metabolic by-products are mostly producing during yeast breeding, we can reduce the yeast proliferation rate by adopting a series of measures such as low-temperature inoculation, inoculum, and low-temperature fermentation. Properly increase the fermentation temperature in the late stage of the main fermentation.

Acids that cause beer fault[edit]

The acids produced during the fermentation of raw materials or during fermentation by yeast are present in a large concentration in beer. When it exceeds 170 mg/litre, it will create a strong sour taste of yogurt or pepper. Acids above the threshold cause significant flavour defects in beer. A hygienic production environment, mashing the yeast strain for less than two hours, and keeping the fermentation temperature lower than 50 °C (122 °F) all help to reduce the amount of acid in beer. Using non-marking brewing supplies and equipment prevents bacteria remaining in scratches of the fermentation device, and contaminating the yeast in the process.[4]

Octanoic[edit]

Octanoic acid (caprylic acid) is a fatty acid produced by the metabolism of yeast during fermentation. When the content of octanoic acid in the beer exceeds 4–6 mg/L, the beer will have a highly concentrated spicy taste. Storage of beer in an environment below 26 °C (79 °F) will reduce this spicy taste. The use of fresh yeast and removal of the beer from the yeast cake immediately after the fermentation process will also keep the octanoic acid content within the threshold.[5]

Butyric[edit]

Butyric acid is an acid produced by bacteria that produces syrup for a beer, or is used to decrease pH value by mixing with oxygen during the production of wort. When the content of butyric acid in beer exceeds 2-3 mg/litre, the beer tastes like metamorphic milk or rotten butter. To avoid this type of defect, acidic sputum should be kept above 90 °F and have minimal contact with oxygen. Beer production environment must be clean. External factors such as pollution during syrup manufacture can also control the content of butyric acid.[6]

Isovaleric[edit]

Isovaleric acid is an acid produced by mixing with octanoic acid in the oxidation of alpha acids in beer, which causes the beer to have an odor. The acid is present in the beer at a level of from 0.7 to 1 mg per litre. A clean and hygienic production environment avoids the mixing of caprylic acid with isovaleric acid. Hops stored in an oxygen-free vacuum tight container prevents bacterial infection.

Alcohols that cause beer fault[edit]

Thiol[edit]

Beers with thiols can produce flavours similar to rotten vegetables or smelly gullies. The threshold for mercaptans in beer is 1 mg/L. Mercaptan is caused by autolysis in the fermentation process of yeast strains, and may also be caused by anaerobic bacterial infection.[7] This can be prevented by removing the beer from the yeast four weeks after the start of the fermentation, thus avoiding the beer absorbing the mercaptan from the dead yeast.

Lightstruck[edit]

Lightstruck causes a sulphur taste in beer. Its cause is the chemical reaction between riboflavin and hop alpha acid in beer under natural light or artificial light. The green bottles used for most beers prevents light increasing its rate of aging. In addition to being packaged in green bottles, storing beer in the dark is also a way to avoid lightstruck.[8]

Aldehyde[edit]

Acetaldehyde[edit]

Acetaldehyde causes beer to taste like green apple when its concentration exceeds the threshold (5–15 mg/L).[9] During the fermentation of beer, the ethanol in yeast can make contact with air if stored improperly, leading to an oxidation reaction that turns it into acetaldehyde. To prevent formation of acetaldehyde, fresh yeast should be fermented at a suitable ambient temperature, and the production environment should be hygienic. After the start of the fermentation, sealing the ingredients with materials of high sealing property prevents oxygen contact. Highly airtight materials used during transportation can reduce oxygen entering the beer.[10]

Phenolic[edit]

The presence threshold of phenolic in beer is 0.05-0.55 mg/L, and beer with phenolic content exceeding the threshold has a bitter and smoky flavour. Using tap water, which contains chlorophenol or chlorine water in disinfectant, as yeast washing water can raise the beer's phenolic acid content after brewing. Ways to reduce phenolic acid content include filtering tap water prior to use, and selecting non-chlorine disinfectants.

Hydrogen sulfide[edit]

Hydrogen sulfide produces a rotten egg flavour in beer. Many yeast strains can produce hydrogen sulfide during the fermentation process. Sulfur is also produced in hops, and during malt manufacturing or wort preparation, although the process of wort boiling removes most of the sulfides.[11] The threshold of hydrogen sulfide in beer is 4 μg/L. To avoid this defect, using healthy yeast and fully oxidized wort increases its zinc content and reduces its hydrogen sulfide content.

Ferrous sulfate[edit]

Ferrous sulfate is caused by the contact of beer with metal materials during the brewing process, resulting in metal ion leaching. Excessive levels of ferrous sulfate can make beer taste like rusty iron and copper. If the content of ferrous sulfate in beer exceeds 1-1.5 mg/L, drinkers will develop symptoms of dizziness. Drinkers may have symptoms of poisoning if the beer has a high concentration of ferrous sulfates. To prevent the formation of ferrous sulfate, the water used for brewing is subjected to a metal ion reaction. Containers for fermented and finished beer should also use food grade plastics. Beer should not come in contact with corrodible containers to reduce the number of metal ions in the beer.[7]

Oxygen[edit]

This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (October 2021) |

Oxygen can cause oxidation, which leads to aging reactions from carbonyl compounds. The original auxiliary material is protected by CO2 or N2 when pulverized, and it is not easy to take too long before smashing. CO2 or N2 protect the equipment during the mashing process, and the bottom feed is used when smashing. The mixing frequency of sputum reduces, and as the stirring speed is reduced, pumps, seals, valves, etc. can not leak.[12] The maintenance can strengthen; when the wort boils, the pot door should close, and the boiling time should finish after the main leaven, and the product should be served as soon as possible. The post-fermenter tank uses CO2 to prepare the pressure, and the speed of the fermentation tank is controlled to be less than 1 m/s.[7]

Dimethyl Sulfide[edit]

Dimethyl sulfide exhibits a sour-sweet cream flavour when it exceeds 0.025 mg/L in beer. Dimethyl sulfide is derived from sulfur-based organic compounds produced during malt development.[13] Bacterial contamination occurs during the fermentation of yeast, which can cause sulphur to produce dimethyl sulfide. If the beer uses malts of sulfur-based organic compounds such as pulses malt or barley malt, the content of dimethyl sulfide would be higher than ordinary ale. Reducing the use of such products prevents this type of defect. Too much water in the wort can also produce large amounts of sulfur-based organic compounds, which can be avoided by storing malt in dry environments.. Based on the volatility of dimethyl sulfide, the wort can be volatilized by boiling at a high temperature for 60 minutes to 90 minutes to remove 90% of dimethyl sulfide.

Oxidation[edit]

Oxidised beer has the moldy taste of old newspapers. Beer with 100% oxygen exposure has the fastest oxidation rate. Temperature is another cause of oxidation, as it produces a lot of oxygen in a high-temperature environment.[14] This oxygen also accelerates the pace of beer oxidation. To avoid excessive beer exposure to oxygen, the headspace reserved for the beer in the bottle should be less than one inch. If the beer is to be stored, the temperature inside its container should be kept below 50 °F (10 °C).[8]

Detecting Beer Faults[edit]

Historically, inspectors had their own methods of testing the quality of beer or checking for specific faults; one example of this is testing if the beer contains too much sugar, which supposedly involved the inspector pouring a small amount onto his chair and sitting down to see if his clothing stuck to the seat. Now, there are guides such as the Complete Beer Fault Guide which explain what to look for and how to detect specific faults by taste, smell, and texture/mouthfeel.[15]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ White, Christopher. "Diacetyl Time Line" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The role of diacetyl in beer". Drayman's. 2016-06-12. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- ^ "Controlling Diacetyl". Brew Your Own. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- ^ "Temperature Factors - How to Brew". howtobrew.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-25. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- ^ Kabay, Nalan (2015), "Boron Removal From Geothermal Water Using Membrane Processes", Boron Separation Processes, Elsevier, pp. 267–283, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-63454-2.00012-5, ISBN 9780444634542

- ^ "The Oxford Companion to Beer Definition of butyric acid,". Craft Beer & Brewing. Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- ^ a b c "18 Common Off Flavors In Beer (And How They're Caused)". Kegerator.com. 2016-07-01. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- ^ a b "Beer bottles: The answer is not clear". Brews News. 2010-08-07. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- ^ "Common Off-Flavors - How to Brew". web.archive.org. 2023-04-24. Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- ^ "Oxygen's Role in the Fermentation of Beer | MoreBeer". www.morebeer.com. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- ^ Micet. "Guide to beer off-flavors: hydrogen sulfide - Micet Craft Brewery Equipment". Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- ^ "Oral Penicillins Can Cause Rapid Severe Anaphylaxis Too". InPharma. 164 (1): 4. November 1978. doi:10.1007/bf03310487. ISSN 0156-2703. S2CID 198224843.

- ^ "Dimethyl Sulfides (DMS) in Home Brewed Beer | Home Brewing Beer Blog by BeerSmith™". beersmith.com. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- ^ "Continuous ethanol fermentation by beer yeast". Journal of Fermentation Technology. 65 (1): 116. January 1987. doi:10.1016/0385-6380(87)90078-1. ISSN 0385-6380.

- ^ Barnes, Thomas. "The complete beer fault guide v. 1.4." (2011).