Bill Ayers

Bill Ayers | |

|---|---|

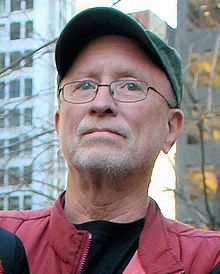

Ayers in 2012 | |

| Born | William Charles Ayers December 26, 1944 Glen Ellyn, Illinois, U.S. |

| Education | University of Michigan (BA) Bank Street College of Education (MEd) Columbia University (MEd, EdD) |

| Known for | Founder of the Weather Underground Urban educational reform |

| Spouse | Bernardine Dohrn |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Education |

| Institutions | University of Illinois at Chicago |

William Charles Ayers (/ɛərz/; born December 26, 1944)[1] is an American retired professor and former militant organizer. In 1969, Ayers co-founded the far-left militant organization the Weather Underground, a revolutionary group that sought to overthrow what they viewed as American imperialism.[2] During the 1960s and 1970s, the Weather Underground conducted a campaign of bombing public buildings in opposition to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. The bombings caused no fatalities, except for three members killed when one of the group's devices accidentally exploded. The FBI described the Weather Underground as a domestic terrorist group.[3] Ayers was hunted as a fugitive for several years, until charges were dropped due to illegal actions by the FBI agents pursuing him and others.

Ayers went on to become a professor in the College of Education at the University of Illinois at Chicago, holding the titles of Distinguished Professor of Education and Senior University Scholar.[4] During the 2008 U.S. presidential campaign, a controversy arose over his contacts with then-candidate Barack Obama. He is married to lawyer and law professor Bernardine Dohrn, who was also a leader in the Weather Underground.

Early life[edit]

Ayers grew up in Glen Ellyn, a suburb of Chicago, Illinois. His parents were Mary (née Andrew) and Thomas G. Ayers, who was later chairman and chief executive officer of Commonwealth Edison (1973 to 1980),[5] and for whom Northwestern's Thomas G. Ayers College of Commerce and Industry was named.[6][7] He attended public schools until his second year in high school, when he transferred to Lake Forest Academy, a small prep school.[8] Ayers earned a Bachelor of Arts in American Studies from the University of Michigan in 1968 (where his father, mother and older brother had preceded him).[8]

Ayers was influenced at a 1965 Ann Arbor teach-in against the Vietnam War, when Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) President Paul Potter, asked his audience, "How will you live your life so that it doesn't make a mockery of your values?" Ayers later wrote in his memoir, Fugitive Days, that his reaction was: "You could not be a moral person with the means to act, and stand still. [...] To stand still was to choose indifference. Indifference was the opposite of moral".[9]

In 1965, Ayers joined a picket line protesting an Ann Arbor, Michigan pizzeria for refusing to seat African Americans. His first arrest came for a sit-in at a local draft board, resulting in ten days in jail. His first teaching job came shortly afterward at the Children's Community School, a preschool with a very small enrollment operating in a church basement, founded by a group of students in emulation of the Summerhill method of education.[10]

The school was a part of the nationwide "free school movement". Schools in the movement had no grades or report cards; they aimed to encourage cooperation rather than competition, and pupils addressed teachers by their first names. Within a few months, at age 21, Ayers became director of the school. There also he met Diana Oughton, who would become his girlfriend until her death in 1970 after a bomb exploded while being prepared for Weather Underground activities.[8]

Early activism[edit]

Ayers became involved in the New Left and the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).[11] He rose to national prominence as an SDS leader in 1968 and 1969 as head of an SDS regional group, the "Jesse James Gang".[12]

The group Ayers headed in Detroit, Michigan, became one of the earliest gatherings of what became the Weathermen. Before the June 1969 SDS convention, Ayers became a prominent leader of the group, which arose as a result of a schism in SDS.[9] "During that time his infatuation with street fighting grew and he developed a language of confrontational militancy that became more and more pronounced over the year [1969]", disaffected former Weathermen member Cathy Wilkerson wrote in 2001. Ayers had previously been a roommate of Terry Robbins, a fellow militant who was killed in 1970 along with Ayers's girlfriend Oughton and one other member in the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion, while constructing anti-personnel bombs (nail bombs) intended for a non-commissioned officer dance at Fort Dix, New Jersey.[13]

In June 1969, the Weathermen took control of the SDS at its national convention, where Ayers was elected Education Secretary.[9] Later in 1969, Ayers participated in planting a bomb at a statue dedicated to police casualties in the 1886 Haymarket affair confrontation between labor supporters and the Chicago police.[14] The blast broke almost 100 windows and blew pieces of the statue onto the nearby Kennedy Expressway.[15] (The statue was rebuilt and unveiled on May 4, 1970, and blown up again by other Weathermen on October 6, 1970.[15][16] Rebuilding it yet again, the city posted a 24-hour police guard to prevent another blast, and in January 1972 it was moved to Chicago police headquarters).[17]

Ayers participated in the Days of Rage riot in Chicago in October 1969, and in December was at the "War Council" meeting in Flint, Michigan. Two major decisions came out of the "War Council". The first was to immediately begin a violent, armed struggle (e.g., bombings and armed robberies) against the state without attempting to organize or mobilize a broad swath of the public. The second was to create underground collectives in major cities throughout the country.[18] Larry Grathwohl, a Federal Bureau of Investigation informant in the Weathermen group from the fall of 1969 to the spring of 1970, stated that "Ayers, along with Bernardine Dohrn, probably had the most authority within the Weathermen".[19]

Involvement with Weather Underground[edit]

After the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion in 1970, in which Weatherman member Ted Gold, Ayers's close friend Terry Robbins, and Ayers's girlfriend, Diana Oughton, were killed when a nail bomb being assembled in the house exploded, Ayers and several associates evaded pursuit by law enforcement officials. Kathy Boudin and Cathy Wilkerson survived the blast. Ayers was not facing criminal charges at the time, but the federal government later filed charges against him.[8]

Ayers participated in the bombings of New York City Police Department headquarters in 1970, the United States Capitol building in 1971, and the Pentagon in 1972, as he noted in his 2001 book, Fugitive Days. Ayers writes:

Although the bomb that rocked the Pentagon was itsy-bitsy—weighing close to two pounds—it caused 'tens of thousands of dollars' of damage. The operation cost under $500, and no one was killed or even hurt.[20]

After the bombing, Ayers became a fugitive. During this time, Ayers and fellow member Bernardine Dohrn married and remained fugitives together, changing identities, jobs and locations.

In 1973, Ayers co-authored the book Prairie Fire with other members of the Weather Underground. The book was dedicated to close to 200 people, including Harriet Tubman, John Brown, "All Who Continue to Fight", and "All Political Prisoners in the U.S."[21] The book dedication includes Sirhan Sirhan, the convicted assassin of Robert F. Kennedy.[22]

In 1973, new information came to light about FBI operations targeted against Weather Underground and the New Left, all part of a series of covert and often illegal FBI projects called COINTEL.[23] Due to the illegal tactics of FBI agents involved with the program, including conducting wiretaps and property searches without warrants, government attorneys requested all weapons-related and bomb-related charges be dropped against the Weather Underground, including charges against Ayers.[24][25]

However, state charges against Dohrn remained. Dohrn was still reluctant to turn herself in to authorities. "He was sweet and patient, as he always is, to let me come to my senses on my own," she later said of Ayers.[8] She turned herself in to authorities in 1980. She was fined $1,500 and given three years probation.[26]

Later reflections on underground period[edit]

Fugitive Days: A Memoir[edit]

In 2001, Ayers published Fugitive Days: A Memoir, which he explained in part as an attempt to answer the questions of Kathy Boudin's son, and his speculation that Diana Oughton died trying to stop the Greenwich Village bomb-makers.[27] Some have questioned the truth, accuracy, and tone of the book. Brent Staples wrote for The New York Times Book Review that "Ayers reminds us often that he can't tell everything without endangering people involved in the story."[28] Historian Jesse Lemisch (himself a former member of SDS) contrasted Ayers's recollections with those of other former members of the Weathermen, and claimed that the book had many errors.[29] Ayers, in the foreword to his book, stated that it was written as his personal memories and impressions over time, not a scholarly research project.[30] Reviewing Ayers's memoir in Slate Magazine, Timothy Noah said that he could not recall reading "a memoir quite so self-indulgent and morally clueless as Fugitive Days".[31] Studs Terkel called Ayers's memoir "a deeply moving elegy to all those young dreamers who tried to live decently in an indecent world".[32]

Statements made in 2001[edit]

Chicago Magazine reported that "just before the September 11th attacks", Richard Elrod, a city lawyer injured in the Weathermen's Chicago "Days of Rage", received an apology from Ayers and Dohrn for their part in the violence. "[T]hey were remorseful," Elrod says. "They said, 'We're sorry that things turned out this way.' "[33]

Much of the controversy about Ayers during the decade since 2000 stems from an interview he gave to Dinitia Smith for The New York Times on the occasion of the memoir's publication on September 11, 2001.[34] The reporter quoted him as saying "I don't regret setting bombs" and "I feel we didn't do enough", and, when asked if he would "do it all again", as responding "I don't want to discount the possibility."[30]

Four days later, Ayers protested the interviewer's characterizations in a Letter to the Editor published September 15, 2001: "This is not a question of being misunderstood or 'taken out of context', but of deliberate distortion."[35] In the ensuing years, Ayers has repeatedly avowed that, when he said he had "no regrets" and that "we didn't do enough", he was speaking only in reference to his efforts to stop the United States from waging the Vietnam War, efforts which he has described as "...inadequate [as] the war dragged on for a decade".[36] Ayers has maintained that the two statements were not intended to imply a wish they had set more bombs.[36][37] In a November 2008 interview with The New Yorker, Ayers said that he had not meant to imply that he wished he and the Weathermen had committed further violence. Instead, he said, "I wish I had done more, but it doesn't mean I wish we'd bombed more shit." Ayers said that he had never been responsible for violence against other people and was acting to end a war in Vietnam in which "thousands of people were being killed every week". He also stated, "While we did claim several extreme acts, they were acts of extreme radicalism against property," and "We killed no one and hurt no one. Three of our people killed themselves."[38]

The interview mentioned an alleged quote of his:

- Kill all the rich people. Break up their cars and apartments. Bring the revolution home, kill your parents, that's where it's really at.[30]

He responded saying that he didn't recall saying that, but that "it's been quoted so many times I'm beginning to think I did. It was a joke about the distribution of wealth.'"[30]

The interviewer also quoted some of Ayers's own criticisms of the Weathermen in the foreword to the memoir, whereby Ayers reacts to having watched Emile de Antonio's 1976 documentary film about the Weathermen, Underground: "[Ayers] was 'embarrassed by the arrogance, the solipsism, the absolute certainty that we and we alone knew the way. The rigidity and the narcissism.' "[30] "We weren't terrorists," Ayers told an interviewer for the Chicago Tribune in 2001. "The reason we weren't terrorists is because we did not commit random acts of terror against people. Terrorism was what was being practiced in the countryside of Vietnam by the United States."[8]

In a letter to the editor in the Chicago Tribune, Ayers wrote, "I condemn all forms of terrorism—individual, group and official". He also condemned the September 11 terrorist attacks in that letter.[39]

Views on his past expressed since 2001[edit]

Ayers was asked in a January 2004 interview, "How do you feel about what you did? Would you do it again under similar circumstances?" He replied:[40] "I've thought about this a lot. Being almost 60, it's impossible to not have lots and lots of regrets about lots and lots of things, but the question of did we do something that was horrendous, awful? [...] I don't think so. I think what we did was to respond to a situation that was unconscionable."

On September 9, 2008, journalist Jake Tapper copied to his ABC News "Political Punch" blog and opined on a four-panel comic strip by Ryan Alexander-Tanner from Bill Ayers's blog site.[41] In the comic strip, the Ayers cartoon character says: "The one thing I don't regret is opposing the war in Vietnam with every ounce of my being... When I say, 'We didn't do enough,' a lot of people rush to think, 'That must mean, "We didn't bomb enough shit." ' But that's not the point at all. It's not a tactical statement, it's an obvious political and ethical statement. In this context, 'we' means 'everyone.' "[41]

After the 2008 presidential election, Ayers published an op-ed piece in The New York Times giving his assessment of his activism. Feminist critic Katha Pollitt criticized Ayers's opinion piece as a "sentimentalized, self-justifying whitewash of his role in the weirdo violent fringe of the 1960s–1970s antiwar left". She says Ayers and his Weathermen cohorts made "the antiwar movement look like the enemy of ordinary people" during the Vietnam War era.[42] Ayers gave this assessment of his actions:

The Weather Underground crossed lines of legality, of propriety and perhaps even of common sense. Our effectiveness can be—and still is being—debated.[43]

He also reiterated his rebuttal to the description of his actions as terrorism despite the use of shrapnel devices:

The Weather Underground went on to take responsibility for placing several small bombs in empty offices... We did carry out symbolic acts of extreme vandalism directed at monuments to war and racism, and the attacks on property, never on people, were meant to respect human life and convey outrage and determination to end the Vietnam war. Peaceful protests had failed to stop the war. So we issued a screaming response. But it was not terrorism; we were not engaged in a campaign to kill and injure people indiscriminately, spreading fear and suffering for political ends.[43]

Academic career[edit]

Ayers is a retired professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, College of Education. His interests include teaching for social justice, urban educational reform, narrative and interpretive research, children in trouble with the law, and related issues.[4]

He began his career in primary education while an undergraduate, teaching at the Children's Community School (CCS), a project founded by a group of students and based on the Summerhill method of education. After leaving the underground, he earned an M.Ed from Bank Street College in Early Childhood Education (1984), an M.Ed from Teachers College, Columbia University in Early Childhood Education (1987) and an Ed.D from Teachers College, Columbia University in Curriculum and Instruction (1987).

Ayers was elected vice president for curriculum studies by the American Educational Research Association in 2008.[44] William H. Schubert, a fellow professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, wrote that his election was "a testimony of [Ayers's] stature and [the] high esteem he holds in the field of education locally, regionally, nationally, and internationally".[45] Writer Sol Stern, a conservative opponent of progressive education policies, has criticized Ayers as having a virulent "hatred of America", and said, "Calling Bill Ayers a school reformer is a bit like calling Joseph Stalin an agricultural reformer."[46][47]

Ayers has edited and written many books and articles on education theory, policy and practice, and has received several honors for his work. His book To Teach: The Journey of A Teacher was named the Kappa Delta Pi Book of the Year in 1993 and subsequently won the Witten award for Distinguished Work in Biography and Autobiography in 1995.[48] On August 5, 2010, Ayers announced his intent to retire from the University of Illinois at Chicago.[49]

On September 23, 2010, William Ayers was unanimously denied emeritus status by the University of Illinois, after a speech by the university's board chair Christopher G. Kennedy (son of assassinated U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy), containing the quote "I intend to vote against conferring the honorific title of our university to a man whose body of work includes a book dedicated in part to the man who murdered my father, Robert F. Kennedy."[50] He added, "There is nothing more antithetical to the hopes for a university that is lively and yet civil...than to permanently seal off debate with one's opponents by killing them".[51] Kennedy referred to a 1974 book Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism, written by Ayers and other Weather Underground members. The book was dedicated to a list of over 200 revolutionary figures, musicians and others, including Sirhan Sirhan, who was convicted of the 1968 assassination of Robert F. Kennedy and sentenced to life in prison.[52] Ayers denied having ever dedicated a book to Sirhan Sirhan and accused right-wing bloggers of having started a rumor to that effect.[53] In an October 2010 Chicago Sun Times editorial entitled Attacks on Ayers distort our history, former students of Ayers and UIC alumni, Daniel Schneider and Adam Kuranishi, responded in opposition to the University of Illinois Board of Trustees' decision to deny Ayers emeritus status.[54]

Civic and political life[edit]

Ayers worked with Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley in shaping the city's school reform program,[55] and was one of three co-authors of the Chicago Annenberg Challenge grant proposal that in 1995 won $49.2 million over five years for public school reform.[56] In 1997, Chicago awarded him its Citizen of the Year award for his work on the project.[57] Since 1999, he has served on the board of directors of the Woods Fund of Chicago, an anti-poverty, philanthropic foundation established as the Woods Charitable Fund in 1941.[58] The Wall Street Journal columnist Thomas Frank praised Ayers as a "model citizen" and a scholar whose "work is esteemed by colleagues of different political viewpoints".[59]

According to Ayers, his radical past occasionally affects him, as when, by his account, he was asked not to attend a progressive educators' conference in the fall of 2006 on the basis that the organizers did not want to risk an association with his past. On January 18, 2009, on his way to speak about education reform at the Centre for Urban Schooling at the University of Toronto, he was refused admission to Canada when he arrived at the Toronto City Centre Airport although he has traveled to Canada more than a dozen times in the past. According to Ayers, "It seems very arbitrary. The border agent said I had a conviction for a felony from 1969. I have several arrests for misdemeanors, but not for felonies."[60]

Political views[edit]

In an interview published in 1995, Ayers characterized his political beliefs at that time and in the 1960s and 1970s: "I am a radical, Leftist, small 'c' communist ... [Laughs] Maybe I'm the last communist who is willing to admit it. [Laughs] We have always been small 'c' communists in the sense that we were never in the Communist party and never Stalinists. The ethics of communism still appeal to me. I don't like Lenin as much as the early Marx. I also like Henry David Thoreau, Mother Jones and Jane Addams [...]".[61]

In 1970, The New York Times called Ayers "a national leader"[62] of the Weatherman organization and "one of the chief theoreticians of the Weathermen".[63] The Weathermen were initially part of the Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM) within the SDS, splitting from the RYM's Maoists by claiming there was no time to build a vanguard party and that revolutionary war against the United States government and the capitalist system should begin immediately. Their founding document called for the establishment of a "white fighting force" to be allied with the "Black Liberation Movement" and other "anti-colonial" movements[64] to achieve "the destruction of US imperialism and the achievement of a classless world: world communism".[65]

In June 1974, the Weather Underground released a 151-page volume titled Prairie Fire, which stated: "We are a guerrilla organization [...] We are communist women and men underground in the United States [...]"[66] The Weatherman leadership, including Ayers, pushed for a radical reformulation of sexual relations under the slogan "Smash Monogamy".[67][68] Radical bomber and feminist[69] Jane Alpert criticized the Weatherman group in 1974 for still being dominated by men, including Ayers, and referred to his "callous treatment and abandonment of Diana Oughton before her death, and for his generally fickle and high-handed treatment of women".[70]

Larry Grathwohl, an undercover FBI agent who infiltrated The Weather Underground, says Ayers told him where to plant bombs. He says Ayers was bent on overthrowing the government. In response to Grathwohl's claims, Ayers stated, "Now that's being blown into dishonest narratives about hurting people, killing people, planning to kill people. That's just not true. We destroyed government property".[71]

On June 18, 2013, Ayers gave an interview to RealClearPolitics' Morning Commute in which he stated that every president in this century should be tried for war crimes, including President Obama for his use of drone attacks, which Ayers considers an act of terror.[72]

Obama–Ayers controversy[edit]

During the 2008 U.S. presidential campaign, a controversy arose about Ayers's contacts with then-candidate Barack Obama, a matter that had been public knowledge in Chicago for years.[73] After being raised by the American and British press,[73][74] the connection was picked up by conservative blogs and newspapers in the United States. The matter was raised in a campaign debate by moderator George Stephanopoulos, and later became an issue for the John McCain presidential campaign. Investigations by The New York Times, CNN, and other news organizations concluded that Obama did not have a close relationship with Ayers.[74][75][76][77]

In an op-ed piece after the election, Ayers denied any close association with Obama, and criticized the Republican campaign for its use of guilt by association tactics.[43]

Personal life[edit]

Ayers is married to Bernardine Dohrn, a fellow former leader of the Weather Underground. They have two adult children, Zayd and Malik, and shared legal guardianship of Chesa Boudin, son of Kathy Boudin and David Gilbert. Boudin and Gilbert were former Weather Underground members who later joined the May 19 Communist Organization and were convicted of felony murder for their roles in that group's Brinks robbery. Chesa Boudin went on to win a Rhodes scholarship[78] and was elected District Attorney of San Francisco in November 2019.[79] Ayers and Dohrn live in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago, in the 21st century.[80][81] His son Zayd is married to actress and writer Rachel DeWoskin, and is on the faculty at Northwestern University.[80][82][83]

Works[edit]

- Education: An American Problem. Bill Ayers, Radical Education Project, 1968, ASIN B0007H31HU OCLC 33088998

- Hot town: Summer in the City: I ain't gonna work on Maggie's farm no more, Bill Ayers, Students for a Democratic Society, 1969, ASIN B0007I3CMI

- Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism, Bernardine Dohrn, Jeff Jones, Billy Ayers, Celia Sojourn, Communications Co., 1974, ASIN B000GF2KVQ OCLC 1177495

- The Good Preschool Teacher: Six Teachers Reflect on Their Lives, William Ayers, Teachers College Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0-8077-2946-5

- To Teach: The Journey of a Teacher, William Ayers, Teachers College Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0-8077-3262-5

- To Become a Teacher: Making a Difference in Children's Lives, William Ayers, Teachers College Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-8077-3455-1

- City Kids, City Teachers: Reports from the Front Row, William Ayers (Editor) and Patricia Ford (Editor), The New Press, 1996, ISBN 978-1-56584-328-8

- A Kind and Just Parent, William Ayers, Beacon Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0-8070-4402-5

- A Light in Dark Times: Maxine Greene and the Unfinished Conversation, Maxine Greene (Editor), William Ayers (Editor), Janet L. Miller (Editor), Teachers College Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0-8077-3721-7

- Teaching for Social Justice: A Democracy and Education Reader, William Ayers (Editor), Jean Ann Hunt (Editor), Therese Quinn (Editor), 1998, ISBN 978-1-56584-420-9

- Teacher Lore: Learning from Our Own Experience, William H. Schubert (editor) and William C. Ayers (editor), Educator's International Press, 1999, ISBN 978-1-891928-03-1

- Teaching from the Inside Out: The Eight-Fold Path to Creative Teaching and Living, Sue Sommers (author), William Ayers (Foreword), Authority Press, 2000, ISBN 978-1-929059-02-7

- A Simple Justice: The Challenge of Small Schools, William Ayers, Teachers College Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0-8077-3963-1

- Zero Tolerance: Resisting the Drive for Punishment, William Ayers (editor), Rick Ayers (editor), Bernardine Dohrn (editor), Jesse L. Jackson (author), The New Press, 2001, ISBN 978-1-56584-666-1

- A School of Our Own: Parents, Power, and Community at the East Harlem Block Schools, Tom Roderick (author), William Ayers (author), Teachers College Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-8077-4157-3 Only the foreword is written by Ayers.

- Refusing Racism: White Allies and the Struggle for Civil Rights, Cynthia Stokes Brown (author), William Ayers (editor), Therese Quinn (editor), Teachers College Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-8077-4204-4

- On the Side of the Child: Summerhill Revisited, William Ayers, Teachers College Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-8077-4400-0

- Fugitive Days: A Memoir, Bill Ayers, Beacon Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8070-7124-2 (Penguin, 2003, ISBN 978-0-14-200255-1)

- Teaching the Personal and the Political: Essays on Hope and Justice, William Ayers, Teachers College Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-8077-4461-1

- Teaching Toward Freedom: Moral Commitment and Ethical Action in the Classroom, William Ayers, Beacon Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-8070-3269-5

- Sing a Battle Song: The Revolutionary Poetry, Statements, and Communiques of the Weather Underground 1970-1974, Bernardine Dohrn, Bill Ayers, and Jeff Jones, Seven Stories Press, 2006, ISBN 978-1-58322-726-8.

- Handbook of Social Justice in Education, William C. Ayers, Routledge, June 2008, ISBN 978-0-8058-5927-0

- City Kids, City Schools: More Reports from the Front Row, Ruby Dee (Foreword), Jeff Chang (Afterword), William Ayers (editor), Billings, Gloria Ladson (editor), Gregory Michie (editor), Pedro Noguera (editor), The New Press, August 2008, ISBN 978-1-59558-338-3

- To Teach: the journey, in comics, William Ayers and Ryan Alexander-Tanner, Jonathan Kozol(Foreword), Teachers College Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-8077-5062-9 This is a graphic novel based on Ayers's To Teach: The Journey of a Teacher. It is not written by him.

- Public Enemy. Confessions of an American Dissident, Bill Ayers, Beacon Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8070-3276-3

- Demand The Impossible: A Radical Manifesto, William Ayers, Haymarket Books, 2016, ISBN 978-1-60846-670-2

- "You Can't Fire the Bad Ones!": And 18 Other Myths about Teachers, Teachers Unions, and Public Education, William Ayers, Crystal Laura, Rick Ayers, Beacon Press, 2018, ISBN 978-0-8070-3666-2

References[edit]

- ^ "Weather Underground Organization (Weatherman)" (PDF). FBI. August 20, 1976. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2008. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ^ The Weathermen's founding manifesto, signed by Ayers and ten others, indicates, "The most important task for us toward making the revolution, and the work our collectives should engage in, is the creation of a mass revolutionary movement...akin to the Red Guard in China, based on the full participation and involvement of masses of people...with a full willingness to participate in the violent and illegal struggle. Ayers, Bill; Mark Rudd; Bernardine Dohrn; Jeff Jones; Terry Robbinson; Gerry Long; Steve Tappis; et al. (1969). You Don't Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows. Weatherman. p. 28. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ^ "Weather Underground Bombings". Federal Bureau Of Investigation. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- ^ a b William Ayers Archived September 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine University of Illinois at Chicago, College of Education

- ^ Jackson, Cheryl V. (June 12, 2007). "Former ComEd CEO; Businessman also fought for equality". Chicago Sun-Times. p. 49. Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ Obituary: Thomas Ayers Served as Board Chair from 1975 to 1986 Archived April 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Northwestern University, June 19, 2007

- ^ "Cinnamon Swirl: Thomas G Ayers, 1915-2007". kimallen.sheepdogdesign.net. June 18, 2007. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Terry, Don (Chicago Tribune staff reporter, "The calm after the storm" Archived February 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Chicago Tribune Magazine, p 10, September 16, 2001, June 8, 2008

- ^ a b c Barber, David, "Fugitive Days; A Memoir - Book Review" Archived October 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Journal of Social History, Winter 2002, retrieved June 10, 2008

- ^ Before "going underground", he published an account of this experience, Education: An American Problem.

- ^ Fugitive Days: A Memoir

- ^ Peter Braunstein; Michael William Doyle, eds. (July 4, 2013). Imagine Nation: The American Counterculture of the 1960s and 70's. Routledge. ISBN 9781136058905. Archived from the original on July 18, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Cathy Wilkerson (December 1, 2001). "Fugitive Days (book review)". Zmag magazine. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013.

- ^ Jacobs, Ron, The way the wind blew: a history of the Weather Underground, London & New York: Verso, 1997. ISBN 1-85984-167-8

- ^ a b Avrich. The Haymarket Tragedy. p. 431.

- ^ Adelman. Haymarket Revisited, p. 40.

- ^ Haymarket Memorial Statue Rededicated at Chicago Police Headquarters Archived January 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Chicago Police Department, June 1, 2007

- ^ Good, "Brian Flanagan Speaks," Next Left Notes, 2005.

- ^ Grathwohl, Larry, and Frank, Reagan, Bringing Down America: An FBI Informant in with the Weathermen, Arlington House, 1977, page 110

- ^ Bill Ayers, Fugitive Days, pg. 261

- ^ Bernardine Dohrn; Billy Ayers; Jeff Jones; Celia Sojourn (May 9, 1974). "Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism:Political Statement of the Weather Underground" (PDF). Communications Co. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ Harvey E. Klehr (1991) Far Left of Center: The American Radical Left Today, Transaction Publishers, p 108 ISBN 0-88738-875-2

- ^ Why Weren't Bill Ayers and Bernadette Dohrn Convicted of Terrorism? Glenrose.net Archived December 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jeremy Varon, Bringing the War Home: the Weather Underground, the Red Army Faction and Revolutionary Violence in the Sixties and Seventies, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), p. 297.

- ^ Peter Jamison, Riverfront Times, Blown to Peaces Archived July 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, September 16, 2009

- ^ Susan Chira, At home with: Bernadine Dohrn; Same Passion, New Tactics Archived July 27, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, November 18, 1993

- ^ Marcia Froelke Coburn, No Regrets Archived May 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Chicago Magazine, August 2001

- ^ Staples, Brent, "The Oldest Rad" Archived July 27, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, book review of Fugitive Days by Bill Ayers in New York Times Book Review, September 30, 2001, accessed June 5, 2008

- ^ Jesse Lemisch, Weather Underground Rises from the Ashes: They're Baack! Archived February 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, New Politics, Summer 2006

- ^ a b c d e Dinitia Smith, No Regrets for a Love Of Explosives; In a Memoir of Sorts, a War Protester Talks of Life With the Weathermen Archived November 23, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, September 11, 2001

- ^ "Radical Chic Resurgent", by Timothy Noah Archived December 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Slate Magazine, August 22, 2001

- ^ Fugitive Days: A Memoir Archived March 13, 2021, at the Wayback Machine at Amazon; scroll down for Terkel blurb.

- ^ Bryan Smith (December 2006). "Sudden Impact". Chicago Magazine. Archived from the original on October 10, 2008. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ^ NB that, although the interview was published on 9/11, it was completed prior to that and cannot be properly construed as a reaction to the events of that day.

- ^ Bill Ayers, Clarifying the Facts— a letter to The New York Times, 9-15-2001 Archived May 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Bill Ayers (blog), April 21, 2008

- ^ a b Bill Ayers, Episodic Notoriety–Fact and Fantasy Archived April 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Bill Ayers (blog), April 6, 2008

- ^ Bill Ayers, WordPress.com Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, I'm Sorry!!!!... I think, Bill Ayers (blog)

- ^ Remnick, David (November 4, 2008). "Mr. Ayers's Neighborhood". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 24, 2008. Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ^ Ayers, Bill, letter to the editor, Chicago Tribune, September 23, 2001, retrieved June 8, 2008

- ^ Web page titled "Weather Underground/ Exclusive interview: Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers" Archived August 31, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Independent Lens website, accessed June 5, 2008

- ^ a b Alexander-Tanner, Ryan (September 2, 2008). "bill ayers speaks". Ryan Alexander-Tanner's blog. ohyesverynice.com. Archived from the original on December 28, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

Ayers, Bill (September 2008). "amessagefrombillayersreformat.jpg". Bill Ayers' blog. billayers.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

Gewargis, Natalie; Tapper, Jake (September 9, 2008). "In a not-remotely-comic strip, Bill Ayers weighs in on what he meant by 'we didn't do enough' to end Vietnam War". Political Punch blog. ABC News. Archived from the original on September 10, 2008. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

Smith, Ben (September 9, 2008). "Ayers explains". Ben Smith's blog. Politico. Archived from the original on December 29, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2013. - ^ Pollitt, Katha. "Bill Ayers Whitewashes History, Again" Archived October 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Nation magazine (December 8, 2008).

- ^ a b c Ayers, William (December 6, 2008). "The Real Bill Ayers". The New York Times. pp. A21. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ^ Aera.net Archived December 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, 2008 AERA Election Results, American Educational Research Association

- ^ Dreyer, Thorne (October 15, 2008). "Dr. William H. Schubert : The Bill Ayers I Know". Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ "The Bomber as School Reformer" Archived January 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, City Journal, October 6, 2008

- ^ "Ayers Is No Education 'Reformer'" Archived July 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine The Wall Street Journal, October 16, 2008

- ^ "William C. Ayers - 2000". Kappa Delti Pi. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ Spak, Kara (August 5, 2010). "Bill Ayers to retire from UIC". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2010. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ Cohen, Jodi (September 23, 2010). "Ayers denied emeritus status after plea from Chris Kennedy". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ Brown, R. (2011) Emeritus Status: It's a Matter of Honor, Especially When It's Denied, The Chronicle of Higher Education 57(43), A8-A9.

- ^ Mercer, David (September 24, 2010). "U. of Ill. denies William Ayers emeritus status". The Charlotte Observer. Retrieved September 24, 2010. [dead link]

- ^

- Spak, Kara (November 4, 2010). "Ayers: Book dedication a lie: '60s radical, retired prof denies paying tribute to Robert Kennedy's killer". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2010.

- "Bill Ayers Denies Dedicating Book To Sirhan Sirhan". The Huffington Post. November 4, 2010. Archived from the original on November 11, 2010. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ "Attacks on Ayers distort our history". Chicago Sun Times. October 10, 2010. Archived from the original on March 8, 2013.

- ^ Mike Dorning and Rick Pearson, Daley: Don't tar Obama for Ayers Archived August 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, The Chicago Tribune, April 17, 2008

- ^ Storch, Charles; Haynes, V. Dion (October 23, 1994). "Schools go after windfall; Millions for reform could be holiday gift". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

Storch, Charles; Haynes, V. Dion (January 21, 1995). "Philanthropist puts his money on city schools". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

Storch, Charles (January 23, 1995). "School reformers getting wish; Unity, commitment led to $49.2 million gift". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

Haynes, V. Dion; Heard, Jacquelyn (January 24, 1995). "A clear present; Annenberg's millions bring hope to Chicago schools". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

Ayers, William; Chapman, Warren; Hallett, Anne (January 31, 1995). "A booster shot for Chicago's public schools". Chicago Tribune. p. 15 (Perspective). Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

Kipen, David (October 3, 2001). "Former '70s radical finds lessons in WTC tragedy". San Francisco Chronicle. p. B1. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

Weissmann, Dan (October 1994). "Reform group maps plan to spend $50 million". Catalyst: A Publication of Community Renewal Society. 6 (2): 24. ISSN 1058-6830.

Weissmann, Dan (March 1995). "Annenberg architects get ball rolling". Catalyst: A Publication of Community Renewal Society. 6 (6): 20–1. ISSN 1058-6830.

Richardson, Lynette (June 1995). "Applications for Annenberg due out soon". Catalyst: A Publication of Community Renewal Society. 6 (9): 20. ISSN 1058-6830.

Shipps, Dorothy; Sconzert, Karin; Swyers, Holly (March 1999). The Chicago Annenberg Challenge: The first three years. Chicago: Consortium on Chicago School Research. OCLC 50759574. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2008. - ^ Griffin, Drew & Johnston, Kathleen (October 7, 2008). "Ayers and Obama crossed paths on boards, records show". CNN. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ Woods Fund of Chicago (2008). "About the Woods Fund: Staff & Board Directory". Woods Fund of Chicago. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ "My Friend Bill Ayers" Archived November 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Wall Street Journal, October 15, 2008

- ^ "Ayers denied entry to Canada" Archived January 23, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Globe and Mail, January 19, 2009

- ^ Chepesiuk, Ron, "Sixties Radicals, Then and Now: Candid Conversations With Those Who Shaped the Era", McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers: Jefferson, North Carolina, 1995, "Chapter 5: Bill Ayers: Radical Educator", p. 102

- ^ Flint, Jerry, M., "2d Blast Victim's Life Is Traced: Miss Oughton Joined a Radical Faction After College", news article, The New York Times, March 19, 1970

- ^ Kifner, John, "That's what the Weathermen are supposed to be ... 'Vandals in the Mother Country'", article, The New York Times magazine, January 4, 1970, page 15

- ^ Berger, Dan (2006). Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity. AK Press. p. 95.

- ^ See document 5, Revolutionary Youth Movement (1969). "You Don't Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows". Archived from the original on March 8, 2008. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ^ Franks, Lucinda, "U.S. Inquiry Finds 37 In Weather Underground", news article, The New York Times, March 3, 1975

- ^ Ron Jacobs, The Way the Wind Blew, p. 46.

- ^ No Regrets for a Love Of Explosives; In a Memoir of Sorts, a War Protester Talks of Life With the Weathermen Archived May 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, September 11, 2001

- ^ Franks, Lucinda (January 14, 1975). "The 4-Year Odyssey of Jane Alpert, From Revolutionary Bomber to Feminist". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ Mother Right: A New Feminist Theory Archived December 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Special Collections Library, Duke University

- ^ Ayers' speech interrupted by protesters Archived February 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine by Alan Wang, ABC7 News, KGO-TV San Francisco, January 28, 2009.

- ^ Bill Ayers: Try Obama for War Crimes. RealClearPolitics. June 18, 2013.

- ^ a b Weiss, Joanna (April 18, 2008). "How Obama and the radical became news". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved November 13, 2008.

- ^ a b Dobbs, Michael (February 19, 2008). "Obama's 'Weatherman' Connection". The Washington Post. The Fact Checker. Archived from the original on May 23, 2011.

- ^ Shane, Scott (October 3, 2008). "Obama and '60s Bomber: A Look Into Crossed Paths". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- ^ "Fact Check: Is Obama 'palling around with terrorists'?". CNN. October 5, 2008. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- ^ "Palin hits Obama for 'terrorist' connection". CNN. October 5, 2008. Archived from the original on June 22, 2015.

- ^ Jodi Wilgoren (December 9, 2002). "From a Radical Background, A Rhodes Scholar Emerges". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 9, 2011. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ^ "Public Defender Chesa Boudin Wins San Francisco D.A. Race in Major Victory for Progressive Prosecutor Movement". November 9, 2019. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ a b Workman, Michael (May 17, 2017). "Why Bill Ayers welcomes strangers into his Hyde Park home for the Chicago Home Theater Festival". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Fusco, Chris; Pallasch, Abdon M. (April 18, 2008). "Who is Bill Ayers?". Chicago Sun-Times. p. 8. Archived from the original on October 8, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ Healy, Patrick (September 2, 2009). "A Playwright's Glimmers of a Fugitive Childhood". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ "Playwright And Chinese Soap Star Meet, Write". HuffPost. January 10, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Bill Ayers collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- 1944 births

- Living people

- American anti-war activists

- American autobiographers

- American communists

- American education writers

- American educational theorists

- American political writers

- American male non-fiction writers

- American anti-poverty advocates

- American anti-racism activists

- American anti-capitalists

- Ayers family

- Bank Street College of Education alumni

- COINTELPRO targets

- Teachers College, Columbia University alumni

- Lake Forest Academy alumni

- Members of Students for a Democratic Society

- Writers from Chicago

- People from Glen Ellyn, Illinois

- University of Illinois Chicago faculty

- University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts alumni

- Members of the Weather Underground

- New Left