User:Polyesterchips/draft

| 1957 Thai coup d'état | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

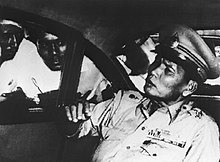

Sarit Thanarat lead the coup | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The 1957 Thai coup d'état

Background[edit]

Phibun regime[edit]

In 1947, a coup d'état ousted the government of Pridi Banomyong's front man, Luang Thamrong, who was replaced by Khuang Aphaiwong, royalist supporter, as Prime Minister of Thailand. The coup was led by military supreme leader, Phibun, and Phin Choonhavan and Kat Katsongkhram, allied with the royalists to regain their political power and the Crown Property back from the Siamese revolution of 1932. An influence of the People Party ended as Pridi left the country on exile. One year later, the junta staged a military coup on 6 April 1948. Khuang Aphaiwong, royalist allied, was forced to resign from prime minister, and was replaced by Phibun, the junta leader.[1]

Two rebellions broke out in October 1948 and Febuary 1949, both related to an exile People Party leader, Pridi Banomyong. Another rebel group called the Manhattan Rebellion in 1951 formed by a group of naval officers.

Phibun then staged a silent coup of 29 November 1951, otherwise known as the Radio Coup, consolidated the military's hold on the country. It reinstated the 1932 constitution, which effectively eliminated the Senate, established a unicameral legislature composed equally of elected and government-appointed members, and allowed serving military officers to supplement their commands with important ministerial portfolios.

Cold War[edit]

After a stalement of the Korean War in 1953 and a lost of France in the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, Phibun government became undecideable to choose side in the Cold War. United States found the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), which Thailand was the first country to join.[2]

Sarit and Pao conflict[edit]

Since the second half of 1955, police chief Phao Siyanon had become more powerful than army chief Sarit Thanarat, because of a support from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and Pao's executive performance. After Phibun went to the U.S., Pao was plotting a coup and wanting to held Sarit in custody but the U.S. opposed to Pao plot. The U.S. deemed Phibun more acceptable leader.[3]

Democratic climate[edit]

Phibun, after learning a democratic climate from the U.S. trip in 1955, acknowledged that both Phao and Sarit were supported by the CIA, he sought alternative way to win more support from Thai people by letting more free speech and demonstrations in Bangkok increasing. Phibun opened hyde park alike at Sanam Luang to solve a political tension, the result of this experiment made Pao more vulnerable.[4]

China connection[edit]

Phibun opened to talk with communist China by sending Wan Waithayakon to meet with the Chinese Communist Party Premier Zhou Enlai in Indonesia in 1955.[5]

Prelude[edit]

Phibun anti-royalist[edit]

Phibun, Pao, and Pridi allied[edit]

Election crisis[edit]

Return of Pridi[edit]

Coup[edit]

Aftermath[edit]

Black May[edit]

The 1991 constitution allowed Suchinda Kraprayoon to be appointed as prime minister. That caused 17–20 May 1992 popular protest in Bangkok against the government of Suchinda and the military crackdown that followed. Up to 200,000 people demonstrated in central Bangkok at the height of the protests. The military crackdown resulted in 52 government-confirmed deaths, hundreds of injuries including journalists, over 3,500 arrests, hundreds of disappearances, and eyewitness reports of a truck filled with bodies leaving the city.[6] Many of those arrested are alleged to have been tortured.[7]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Chaiching 2010.

- ^ Chaiching 2020, p. 169-170.

- ^ Chaiching 2020, p. 177-178.

- ^ Chaiching 2020, p. 178-190.

- ^ Chaiching 2020, p. 191-200.

- ^ Bloody May: Excessive Use of Lethal Force in Bangkok; The Events of May 17–20, 1992; A Report by Asia Watch and Physicians for Human Rights (Draft). Asia Watch and Physicians for Human Rights. 1992-09-23. ISBN 1-879707-10-1. Retrieved 2018-10-07.

- ^ New York Times 1957.

Bibliography[edit]

- Chaiching, Nattapoll (2009). "Thai Politics in Phibun" s Government under the US World Order (1948-1957)" (PDF) (in Thai). Chulalongkorn University.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Chaiching, Nattapoll (2010). Ivarsson, Søren; Isager, Lotte (eds.). "The Monarchy and the royalist Movement in Modern Thai politics, 1932–1957". Saying the Unsayable : Monarchy and Democracy in Thailand. NIAS Press: 147–178.

- Chaiching, Nattapoll (2020). ขุนศึก ศักดินา และพญาอินทรี: การเมืองไทยภายใต้ระเบียบโลกของสหรัฐอเมริกา 2491-2500 (in Thai). Nonthaburi: Samesky. ISBN 978-616-7667-88-1.

- New York Times (13 September 1957a). "New Resignation Stirs Thai Crisis; Phao, Leading Party Aide Of Premier, Quits Ministry On Military's Demand". timesmachine.nytimes.com. New York Times.

- New York Times (14 September 1957b). "Thai Army Leaders Ask Pibul To Resign". timesmachine.nytimes.com. New York Times.

- New York Times (17 September 1957c). "Thai Army Seizes Control In Coup". timesmachine.nytimes.com. New York Times.

- New York Times (18 September 1957d). "Thailand Is Calm After Army Coup". timesmachine.nytimes.com. New York Times.

- New York Times (14 September 1957b). "Thailand's Strong Man: Sarit Thanarat". timesmachine.nytimes.com. New York Times.